Visual Food Ingredient Prediction Using Deep Learning with Direct F-Score Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We present a novel cost-sensitive formulation for direct F-score optimization. This formulation can be utilized in both single and multiple output scenarios, and for both micro and macro F-scores.

- We provide a practical approximation algorithm that enables deep learning model training without additional computation.

- We conducted comprehensive experiments on the Recipe1M dataset comparing CNN and ViT architectures for visual food ingredient prediction. These experiments provide insights into their relative strengths and limitations.

- We demonstrated that our method offers substantial improvements over alternative F-score optimization approaches. These alternatives include searching for the optimal relative misclassification cost and soft loss. Our method also outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods on food ingredient prediction.

2. Related Work

2.1. Food Ingredient Prediction

2.2. F-Score Optimization

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Model Architecture

3.2. F-Score Optimization

3.2.1. Motivation

3.2.2. Optimal Derivation

3.2.3. Practical Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Fola: Training neural network to maximize -score |

|

3.2.4. Considerations for Macro F-Score Optimization

3.2.5. Alternative Approach

4. Results

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Baselines

- InverseCooking [51] employs ResNet50 as the image encoder and either a set transformer (denoted ) or feedforward network (denoted ) as the ingredient decoder. We used the set transformer variant as the primary baseline due to its superior performance.

- BCE w/ fixed uses a fixed value for the parameter of the BCE loss function. We evaluated multiple values to demonstrate the impact of suboptimal class weight selection.

- Soft employs a differentiable version of F-score as the loss function directly by replacing hard counts with sums of predicted probability. This approach does not rely on auxiliary loss functions such as BCE.

4.4. Model Comparison for Micro F1 Score

4.4.1. Overall Prediction Performance

4.4.2. Cardinality Analysis

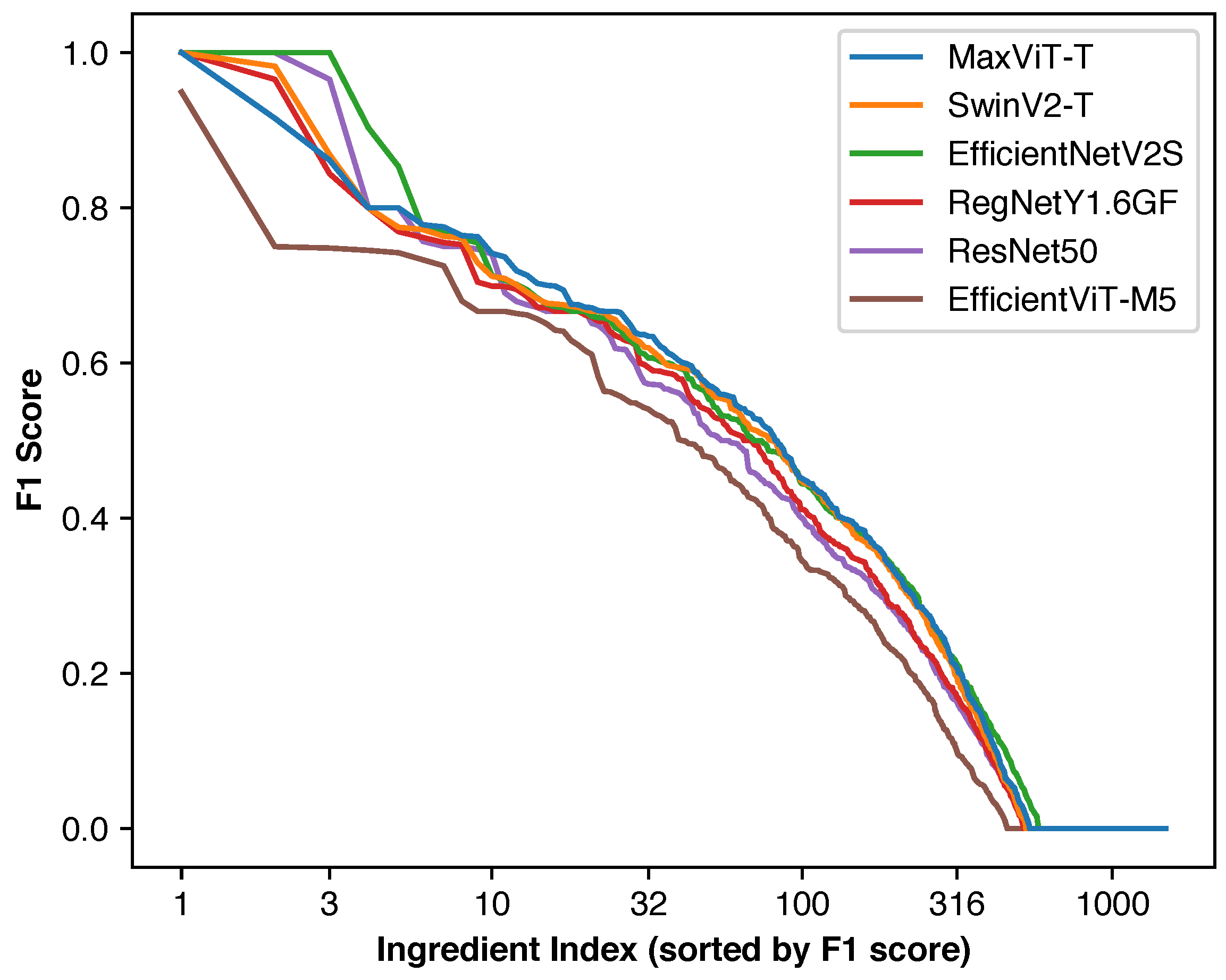

4.4.3. Individual Ingredient Performance Distribution

4.5. F-Score Optimization Method Comparison for Micro F1 Score

4.6. Model Comparison for Macro F1 Score

4.6.1. Overall Prediction Performance

4.6.2. Cardinality Analysis

4.6.3. Individual Ingredient Performance Distribution

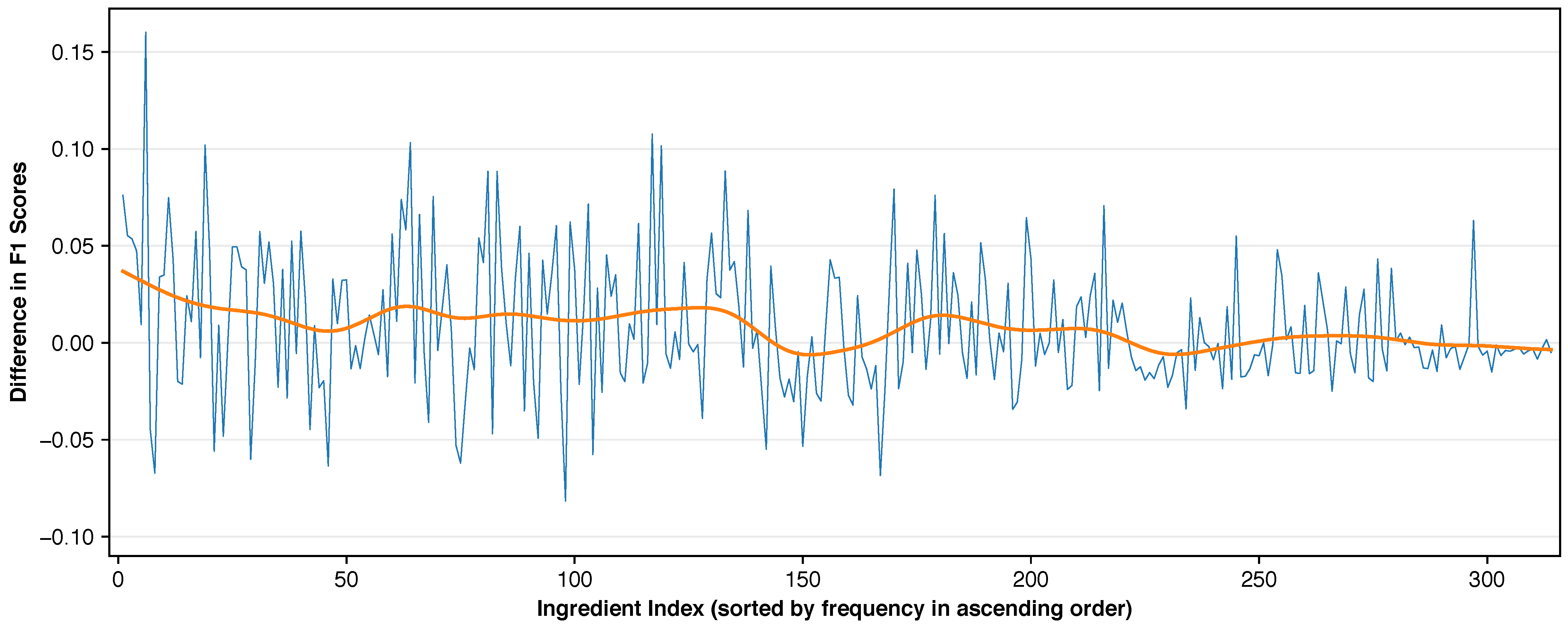

4.6.4. Micro vs. Macro F1 Score Performance Analysis

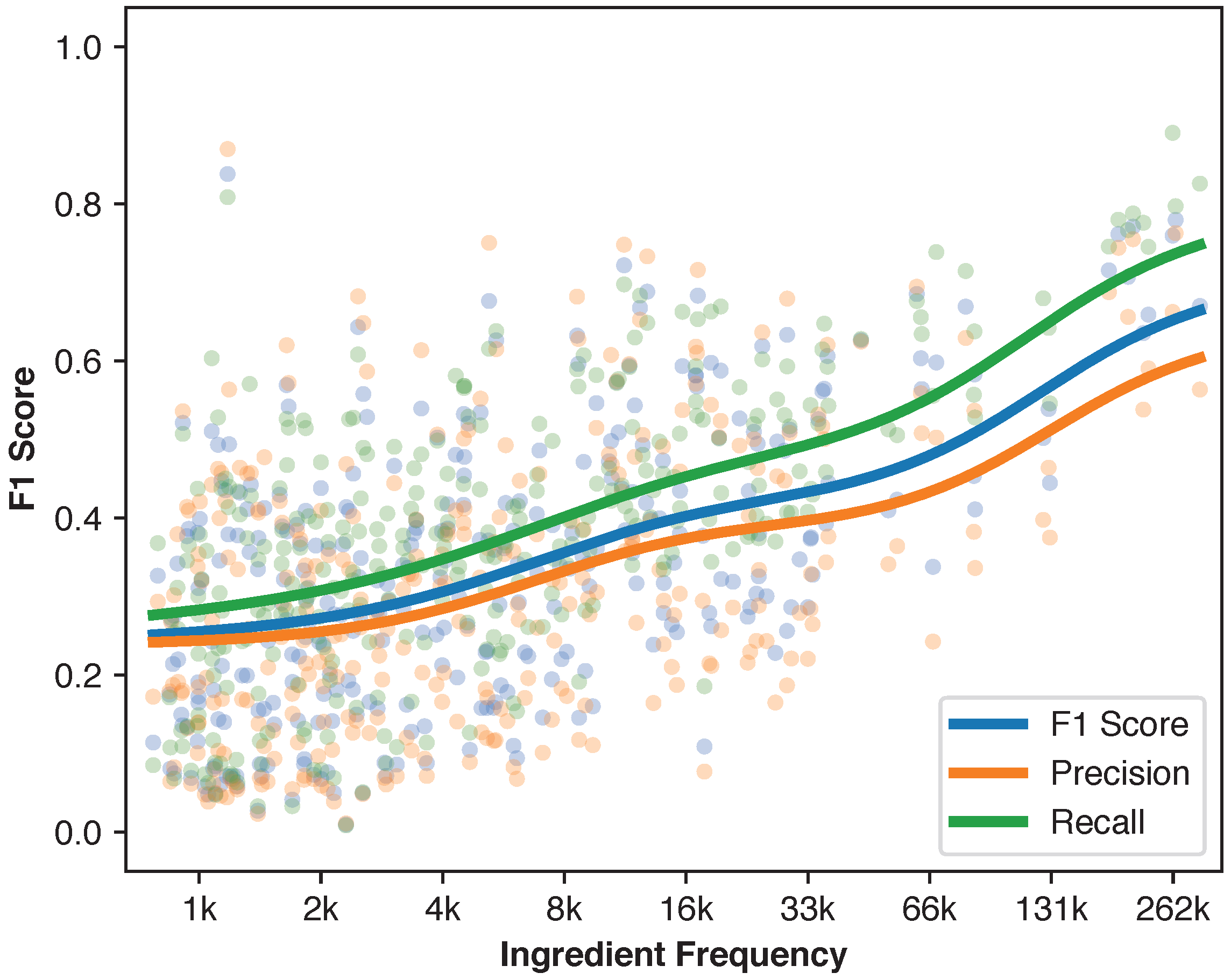

4.6.5. Ingredient Frequency vs. Prediction Accuracy

4.7. F-Score Optimization Method Comparison for Macro F1 Score

4.8. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| ViT | Vision transformer |

| Pr | Precision |

| Rc | Recall |

| BCE | Binary cross-entropy |

| SGD | Stochastic gradient descent |

| TP | True positive |

| FP | False positive |

| FN | False negative |

| M | Million |

| FC | Fully connected |

| GFLOPS | Giga floating point operations per second |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| CLR | Cyclical learning rates |

| LR | Learning rates |

| IoU | Intersection over union |

| TN | True negative |

References

- Achananuparp, P.; Lim, E.P.; Abhishek, V. Does journaling encourage healthier choices? Analyzing healthy eating behaviors of food journalers. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Digital Health, Lyon, France, 23–26 April 2018; pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.C.; Onthoni, D.D.; Mohapatra, S.; Irianti, D.; Sahoo, P.K. Deep-learning-assisted multi-dish food recognition application for dietary intake reporting. Electronics 2022, 11, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, E.; Nagarajan, B.; Radeva, P. Uncertainty-aware selecting for an ensemble of deep food recognition models. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 146, 105645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokhva, S.; Teimourpour, B.; Soltani, A.H. Computer vision in the food industry: Accurate, real-time, and automatic food recognition with pretrained MobileNetV2. Food Humanit. 2024, 3, 100378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shen, R.; Zheng, G.; Fu, X.; Yu, X.; Jiang, J. An interactive food recommendation system using reinforcement learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 254, 124313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Feng, F.; Huang, H.; Mao, X.L.; Lan, T.; Chi, Z. Food recommendation with graph convolutional network. Inf. Sci. 2022, 584, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Duan, L.Y.; Jiang, H.; Jing, P.; Song, X.; Nie, L. Market2Dish: Health-aware food recommendation. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2021, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.S.; Fidalgo, F.; Oliveira, A. RecipeIS—Recipe Recommendation System Based on Recognition of Food Ingredients. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Han, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Kong, D.; Zou, X. Strawberry detection and ripeness classification using yolov8+ model and image processing method. Agriculture 2024, 14, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanth, J.; Mahadevaswamy, M.; Shivakumar, M. Fruit quality identification and classification by convolutional neural network. SN Comput. Sci. 2023, 4, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Bansal, A. Classification and grading of multiple varieties of apple fruit. Food Anal. Methods 2021, 14, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofli, F.; Aytar, Y.; Weber, I.; Al Hammouri, R.; Torralba, A. Is saki# delicious? the food perception gap on instagram and its relation to health. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 509–518. [Google Scholar]

- Sajadmanesh, S.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Ossia, S.A.; Rabiee, H.R.; Haddadi, H.; Mejova, Y.; Musolesi, M.; Cristofaro, E.D.; Stringhini, G. Kissing cuisines: Exploring worldwide culinary habits on the web. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web Companion, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 1013–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Elsweiler, D.; Trattner, C. Understanding and predicting cross-cultural food preferences with online recipe images. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.S.; Chen, G.Y.; Zhou, D.; Jiang, D.; Chen, D.S. Res-vmamba: Fine-grained food category visual classification using selective state space models with deep residual learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.15761. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Zhu, F. Online continual learning for visual food classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 2337–2346. [Google Scholar]

- Nfor, K.A.; Armand, T.P.T.; Ismaylovna, K.P.; Joo, M.I.; Kim, H.C. An Explainable CNN and Vision Transformer-Based Approach for Real-Time Food Recognition. Nutrients 2025, 17, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvador, A.; Hynes, N.; Aytar, Y.; Marin, J.; Ofli, F.; Weber, I.; Torralba, A. Learning cross-modal embeddings for cooking recipes and food images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3020–3028. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16×16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuneki, M. Deep learning models in medical image analysis. J. Oral Biosci. 2022, 64, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, M.; Kandhasamy, S.; Chokkalingam, B.; Mihet-Popa, L. A comprehensive review on deep learning-based motion planning and end-to-end learning for self-driving vehicle. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 66031–66067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichen, M. Generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Delhi, India, 6–8 July 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Diao, G.; Deng, Z. Fine grained food image recognition based on swin transformer. J. Food Eng. 2024, 380, 112134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; He, J.; Shao, Z.; Yarlagadda, S.K.; Zhu, F. Visual aware hierarchy based food recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Xiamen, China, 24–26 September 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 571–598. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, L.; Nnamoko, N.; Lopes, R. Fine-grained food image recognition: A study on optimising convolutional neural networks for improved performance. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, W.; Jiang, S.; Liu, L.; Rui, Y.; Jain, R. A survey on food computing. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 52, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossard, L.; Guillaumin, M.; Van Gool, L. Food-101–mining discriminative components with random forests. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Proceedings, Part VI 13. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 446–461. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.; Yang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Chen, Y.T.; Parekh, Z.; Pham, H.; Le, Q.; Sung, Y.H.; Li, Z.; Duerig, T. Scaling up visual and vision-language representation learning with noisy text supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Online, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 4904–4916. [Google Scholar]

- Foret, P.; Kleiner, A.; Mobahi, H.; Neyshabur, B. Sharpness-aware minimization for efficiently improving generalization. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.01412. [Google Scholar]

- Martinel, N.; Foresti, G.L.; Micheloni, C. Wide-slice residual networks for food recognition. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 567–576. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Kornblith, S.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. Do better ImageNet models transfer better? In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 2661–2671. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 13–18 July 2020; pp. 1597–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Zhou, F.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Lin, Y.; Belongie, S. Kernel pooling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2921–2930. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.; Wang, D.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Deep layer aggregation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 2403–2412. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.Y.; Yang, Y.H.; Ho, C.J.; Wang, S.H.; Liu, S.M.; Chang, E.; Yeh, C.H.; Ouhyoung, M. Automatic chinese food identification and quantity estimation. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia 2012 Technical Briefs, Singapore, 28 November–1 December 2012; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Min, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Luo, M.; Kang, L.; Wei, X.; Wei, X.; Jiang, S. Large scale visual food recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 9932–9949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, Y.; Hoashi, H.; Yanai, K. Recognition of multiple-food images by detecting candidate regions. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo, Melbourne, Australia, 9–13 July 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Theera-Ampornpunt, N.; Treepong, P. Thai Food Recognition Using Deep Learning with Cyclical Learning Rates. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 174204–174221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, Y.; Yanai, K. Automatic expansion of a food image dataset leveraging existing categories with domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2014 Workshops, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–7 and 12 September 2014; Proceedings, Part III 13. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, P.; Sikka, K.; Wang, W.; Belongie, S.; Divakaran, A. FoodX-251: A dataset for fine-grained food classification. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.06167. [Google Scholar]

- Min, W.; Liu, L.; Luo, Z.; Jiang, S. Ingredient-guided cascaded multi-attention network for food recognition. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Nice, France, 21–25 October 2019; pp. 1331–1339. [Google Scholar]

- Min, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Luo, Z.; Wei, X.; Wei, X.; Jiang, S. ISIA Food-500: A dataset for large-scale food recognition via stacked global-local attention network. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 393–401. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Jia, W.; Bucher, T.; Zhang, H.; Sun, M. Image-based food portion size estimation using a smartphone without a fiducial marker. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1180–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, G.; He, J.; Shao, Z.; Zhu, F. Food Portion Estimation via 3D Object Scaling. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 3741–3749. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, A.; Johnston, N.; Rathod, V.; Korattikara, A.; Gorban, A.; Silberman, N.; Guadarrama, S.; Papandreou, G.; Huang, J.; Murphy, K.P. Im2Calories: Towards an automated mobile vision food diary. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1233–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Dehais, J.; Anthimopoulos, M.; Shevchik, S.; Mougiakakou, S. Two-view 3D reconstruction for food volume estimation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2016, 19, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Tan, W.; Ma, L.; Wang, Y.; Tang, W. MUSEFood: Multi-Sensor-based food volume estimation on smartphones. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE SmartWorld, Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Advanced & Trusted Computing, Scalable Computing & Communications, Cloud & Big Data Computing, Internet of People and Smart City Innovation (SmartWorld/SCALCOM/UIC/ATC/CBDCom/IOP/SCI), Leicester, UK, 19–23 August 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 899–906. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Ngo, C.W. Deep-based ingredient recognition for cooking recipe retrieval. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 15–19 October 2016; pp. 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Liang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Qian, X.; Fu, J. Food and ingredient joint learning for fine-grained recognition. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2020, 31, 2480–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, A.; Drozdzal, M.; Giró-i Nieto, X.; Romero, A. Inverse cooking: Recipe generation from food images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 10453–10462. [Google Scholar]

- Chhikara, P.; Chaurasia, D.; Jiang, Y.; Masur, O.; Ilievski, F. Fire: Food image to recipe generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January, 2024; pp. 8184–8194. [Google Scholar]

- Jansche, M. Maximum expected F-measure training of logistic regression models. In Proceedings of the Human Language Technology Conference and Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–8 October 2005; pp. 692–699. [Google Scholar]

- Koyejo, O.; Natarajan, N.; Ravikumar, P.; Dhillon, I.S. Consistent binary classification with generalized performance metrics. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, N.; Chai, K.M.A.; Lee, W.S.; Chieu, H.L. Optimizing F-measures: A tale of two approaches. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning, Edinburgh, UK, 26 June–1 July 2012; pp. 1555–1562. [Google Scholar]

- Joachims, T. A support vector method for multivariate performance measures. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Machine Learning, Bonn, Germany, 7–11 August 2005; pp. 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Musicant, D.R.; Kumar, V.; Ozgur, A. Optimizing F-Measure with Support Vector Machines. In Proceedings of the FLAIRS, St. Augustine, FL, USA, 12–14 May 2003; pp. 356–360. [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan, H.; Kar, P.; Jain, P. Optimizing non-decomposable performance measures: A tale of two classes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Lille, France, 6–11 July 2015; pp. 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan, H.; Vaish, R.; Agarwal, S. On the statistical consistency of plug-in classifiers for non-decomposable performance measures. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Petterson, J.; Caetano, T. Reverse multi-label learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 23, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–9 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Petterson, J.; Caetano, T. Submodular multi-label learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 24, Granada, Spain, 12–15 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, R.E.; Lin, C.J. A Study on Threshold Selection for Multi-Label Classification; Department of Computer Science, National Taiwan University: Taipei, Taiwan, 2007; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, Z.C.; Elkan, C.; Naryanaswamy, B. Optimal thresholding of classifiers to maximize F1 measure. In Proceedings of the Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Nancy, France, 15–19 September 2014; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Pillai, I.; Fumera, G.; Roli, F. F-measure optimisation in multi-label classifiers. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR2012), Tsukuba, Japan, 11–15 November 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 2424–2427. [Google Scholar]

- Pillai, I.; Fumera, G.; Roli, F. Threshold optimisation for multi-label classifiers. Pattern Recognit. 2013, 46, 2055–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Pellicer, J.; Zamora-Martínez, F.; España-Boquera, S.; Castro-Bleda, M.J. F-measure as the error function to train neural networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Computational Intelligence: 12th International Work-Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, IWANN 2013, Puerto de la Cruz, Spain, 12–14 June 2013; Proceedings, Part I 12. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 376–384. [Google Scholar]

- Puthiya Parambath, S.; Usunier, N.; Grandvalet, Y. Optimizing F-measures by cost-sensitive classification. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eban, E.; Schain, M.; Mackey, A.; Gordon, A.; Rifkin, R.; Elidan, G. Scalable learning of non-decomposable objectives. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, PMLR, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 832–840. [Google Scholar]

- Theera-Ampornpunt, N.; Treepong, P.; Phokabut, N.; Phlaichana, S. KediNet: A Hybrid Deep Learning Architecture for Thai Dessert Recognition. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 86935–86948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Talebi, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, F.; Milanfar, P.; Bovik, A.; Li, Y. Maxvit: Multi-axis vision transformer. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 459–479. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, H.; Lin, Y.; Yao, Z.; Xie, Z.; Wei, Y.; Ning, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, L.; et al. Swin transformer v2: Scaling up capacity and resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 12009–12019. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. EfficientNetV2: Smaller models and faster training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 10096–10106. [Google Scholar]

- Radosavovic, I.; Kosaraju, R.P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Designing network design spaces. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–20 June 2020; pp. 10428–10436. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Peng, H.; Zheng, N.; Yang, Y.; Hu, H.; Yuan, Y. Efficientvit: Memory efficient vision transformer with cascaded group attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 14420–14430. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, A.; Mohri, M.; Zhong, Y. Cross-entropy loss functions: Theoretical analysis and applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 23803–23828. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.N. Cyclical learning rates for training neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 27–31 March 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 464–472. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.01703. [Google Scholar]

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. ImageNet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Architecture | Parameters | GFLOPS |

|---|---|---|

| MaxViT-T [70] | 30.9 M | 5.56 |

| SwinV2-T [71] | 28.4 M | 5.94 |

| EfficientNetV2-S [72] | 20.3 M | 8.37 |

| RegNetY-1.6GF [73] | 9.9 M | 1.61 |

| ResNet-50 [74] | 23.6 M | 4.09 |

| EfficientViT-M5 [75] | 12.4 M | 0.52 |

| Number | Ingredient | Frequency | Number | Ingredient | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Salt | 361,020 | 16 | Tomato | 94,961 |

| 2 | Sugar | 312,773 | 17 | Baking Powder | 80,253 |

| 3 | Pepper | 308,828 | 18 | Garlic | 79,688 |

| 4 | Butter | 269,332 | 19 | Cinnamon | 73,871 |

| 5 | Cooking Oil | 259,742 | 20 | Baking Soda | 73,540 |

| 6 | Egg | 245,942 | 21 | Chicken | 72,885 |

| 7 | Onion | 239,661 | 22 | Vinegar | 64,648 |

| 8 | Flour | 227,431 | 23 | Parsley | 61,112 |

| 9 | Cheese | 212,610 | 24 | Potato | 52,350 |

| 10 | Milk | 152,686 | 25 | Broth | 44,583 |

| 11 | Water | 151,490 | 26 | Carrot | 43,953 |

| 12 | Garlic Cloves | 146,192 | 27 | Basil | 42,752 |

| 13 | Juice | 99,735 | 28 | Beef | 41,401 |

| 14 | Cream | 99,307 | 29 | Soy Sauce | 41,373 |

| 15 | Flavor Extract | 99,206 | 30 | Chips | 40,015 |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Batch Size | 512 |

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Momentum | None |

| Weight Decay | 0.001 |

| LR Schedule | CLR triangular policy [77] with initial LR of 0.05 of maximum LR |

| Training Length | 20 epochs |

| Data Augmentation | Random horizontal flip |

| Dropout Rate | 0.2 |

| Label Smoothing | None |

| Model | IoU | F1 Score | Pr | Rc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| InverseCooking | 0.3211 | 0.4861 | - | - |

| FIRE | 0.3259 | 0.4927 | - | - |

| MaxViT-T | 0.4014 ± 0.0003 | 0.5616 ± 0.0006 | 0.5408 ± 0.0043 | 0.5841 ± 0.0040 |

| SwinV2-T | 0.3988 ± 0.0016 | 0.5593 ± 0.0013 | 0.5366 ± 0.0020 | 0.5842 ± 0.0034 |

| EfficientNetV2-S | 0.3931 ± 0.0006 | 0.5522 ± 0.0007 | 0.5171 ± 0.0014 | 0.5924 ± 0.0008 |

| RegNetY-1.6GF | 0.3856 ± 0.0005 | 0.5454 ± 0.0002 | 0.5257 ± 0.0006 | 0.5667 ± 0.0011 |

| ResNet-50 | 0.3693 ± 0.0013 | 0.5284 ± 0.0018 | 0.5083 ± 0.0011 | 0.5503 ± 0.0049 |

| EfficientViT-M5 | 0.3552 ± 0.0045 | 0.5120 ± 0.0057 | 0.4874 ± 0.0088 | 0.5392 ± 0.0021 |

| Model | Cardinality | MAE | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground Truth | 8.03 ± 3.09 | - | - |

| 8.02 ± 3.24 | 3.02 ± 2.50 | 0.4594 | |

| 9.43 ± 2.35 | 2.56 ± 1.93 | 0.4861 | |

| MaxViT-T | 8.68 ± 3.00 | 2.42 ± 2.03 | 0.5620 |

| SwinV2-T | 8.66 ± 2.95 | 2.42 ± 2.02 | 0.5595 |

| EfficientNetV2-S | 9.23 ± 3.09 | 2.61 ± 2.14 | 0.5514 |

| RegNetY-1.6GF | 8.66 ± 3.02 | 2.48 ± 2.07 | 0.5456 |

| ResNet-50 | 8.80 ± 3.14 | 2.61 ± 2.16 | 0.5305 |

| EfficientViT-M5 | 8.73 ± 2.97 | 2.57 ± 2.12 | 0.5186 |

| Loss Function | IoU | F1 Score | Pr | Rc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| soft | 0.3671 ± 0.0025 | 0.5305 ± 0.0027 | 0.5560 ± 0.0005 | 0.5073 ± 0.0045 |

| BCE with | 0.3786 ± 0.0015 | 0.5394 ± 0.0005 | 0.6185 ± 0.0106 | 0.4783 ± 0.0070 |

| BCE with | 0.3960 ± 0.0005 | 0.5574 ± 0.0003 | 0.5904 ± 0.0033 | 0.5279 ± 0.0032 |

| Fola () | 0.4014 ± 0.0003 | 0.5616 ± 0.0006 | 0.5408 ± 0.0043 | 0.5841 ± 0.0040 |

| BCE with | 0.3949 ± 0.0016 | 0.5536 ± 0.0015 | 0.4905 ± 0.0031 | 0.6352 ± 0.0023 |

| BCE with | 0.3761 ± 0.0042 | 0.5309 ± 0.0034 | 0.4387 ± 0.0106 | 0.6727 ± 0.0145 |

| Model | IoU | F1 Score | Pr | Rc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MaxViT-T | 0.3717 ± 0.0012 | 0.3390 ± 0.0009 | 0.3123 ± 0.0040 | 0.3863 ± 0.0092 |

| SwinV2-T | 0.3696 ± 0.0005 | 0.3357 ± 0.0009 | 0.2998 ± 0.0018 | 0.4008 ± 0.0030 |

| EfficientNetV2-S | 0.3611 ± 0.0007 | 0.3245 ± 0.0005 | 0.2812 ± 0.0007 | 0.4013 ± 0.0014 |

| RegNetY-1.6GF | 0.3597 ± 0.0004 | 0.3164 ± 0.0012 | 0.2930 ± 0.0021 | 0.3592 ± 0.0005 |

| ResNet-50 | 0.3432 ± 0.0002 | 0.2935 ± 0.0009 | 0.2746 ± 0.0021 | 0.3301 ± 0.0032 |

| EfficientViT-M5 | 0.3253 ± 0.0002 | 0.2653 ± 0.0006 | 0.2381 ± 0.0023 | 0.3141 ± 0.0040 |

| Model | Cardinality | MAE | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground Truth | 7.85 ± 3.08 | - | - |

| MaxViT-T | 10.41 ± 4.06 | 3.51 ± 2.84 | 0.3399 |

| SwinV2-T | 10.94 ± 4.13 | 3.84 ± 3.02 | 0.3367 |

| EfficientNetV2-S | 11.30 ± 4.30 | 4.11 ± 3.21 | 0.3241 |

| RegNetY-1.6GF | 10.55 ± 4.12 | 3.65 ± 2.97 | 0.3156 |

| ResNet-50 | 10.68 ± 4.24 | 3.86 ± 3.09 | 0.2944 |

| EfficientViT-M5 | 11.00 ± 4.40 | 4.10 ± 3.27 | 0.2651 |

| Loss Function | IoU | F1 Score | Pr | Rc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| soft | 0.3736 ± 0.0024 | 0.1538 ± 0.0012 | 0.1615 ± 0.0052 | 0.1706 ± 0.0041 |

| Fola (unbounded) | 0.3668 ± 0.0026 | 0.3352 ± 0.0012 | 0.3076 ± 0.0021 | 0.3865 ± 0.0031 |

| Fola (bounded) | 0.3717 ± 0.0012 | 0.3390 ± 0.0009 | 0.3123 ± 0.0040 | 0.3863 ± 0.0092 |

| BCE with | 0.3963 ± 0.0003 | 0.3260 ± 0.0015 | 0.4166 ± 0.0025 | 0.2871 ± 0.0028 |

| BCE with | 0.4000 ± 0.0002 | 0.3368 ± 0.0014 | 0.3813 ± 0.0020 | 0.3193 ± 0.0025 |

| BCE with | 0.3985 ± 0.0003 | 0.3362 ± 0.0005 | 0.3521 ± 0.0043 | 0.3497 ± 0.0037 |

| BCE with | 0.3831 ± 0.0011 | 0.3373 ± 0.0006 | 0.3107 ± 0.0045 | 0.3962 ± 0.0052 |

| BCE with | 0.3677 ± 0.0015 | 0.3336 ± 0.0016 | 0.2792 ± 0.0035 | 0.4287 ± 0.0035 |

| BCE with | 0.3612 ± 0.0015 | 0.3241 ± 0.0015 | 0.2745 ± 0.0023 | 0.4097 ± 0.0012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Theera-Ampornpunt, N.; Treepong, P. Visual Food Ingredient Prediction Using Deep Learning with Direct F-Score Optimization. Foods 2025, 14, 4269. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244269

Theera-Ampornpunt N, Treepong P. Visual Food Ingredient Prediction Using Deep Learning with Direct F-Score Optimization. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4269. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244269

Chicago/Turabian StyleTheera-Ampornpunt, Nawanol, and Panisa Treepong. 2025. "Visual Food Ingredient Prediction Using Deep Learning with Direct F-Score Optimization" Foods 14, no. 24: 4269. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244269

APA StyleTheera-Ampornpunt, N., & Treepong, P. (2025). Visual Food Ingredient Prediction Using Deep Learning with Direct F-Score Optimization. Foods, 14(24), 4269. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244269