Citri grandis Exocarpium Extract Alleviates Atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− Mice by Modulating the Expression of TGF-β1, PI3K, AKT1, PPAR-γ, LXR-α, and ABCA1

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Chemical Reagents

2.2. Cell Lines and Animals

2.3. Preparation of CGE

2.4. HPLC Fingerprint Procedure

2.5. Standard Solution and Sample Solution Preparation

2.6. Cell Viability Assay

2.7. LDH Release Assay

2.8. Oil Red O Staining for Cholesterol-Induced HUVECs

2.9. In Vitro Cell Migration and Invasion Assay

2.10. Modeling and Grouping

2.11. Sample Collection and Preparation

2.12. Biochemical Detection

2.13. Oil Red O Lipid-Staining Assay

2.14. Histopathology Examination and Collagen Deposition Evaluation

2.15. Gene Expression Analysis via RT-qPCR

2.16. Western Blot Analysis

2.17. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phytochemical Characterization via HPLC Analysis

3.2. CGE Prevents Cholesterol-Induced Endothelial Injury

3.3. Serum Lipid Profile and Transaminase Levels

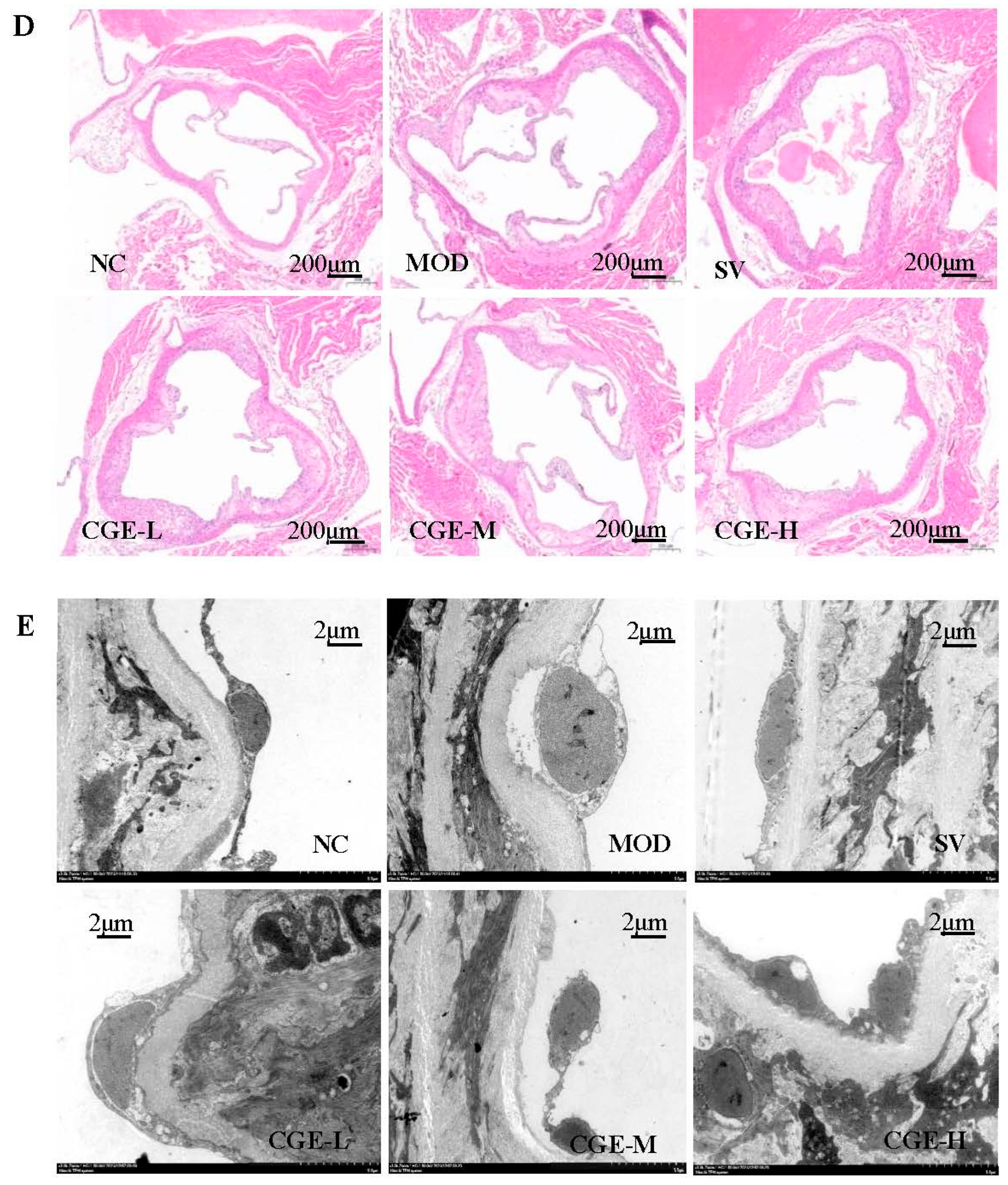

3.4. Pathological Examination of Mouse Aorta

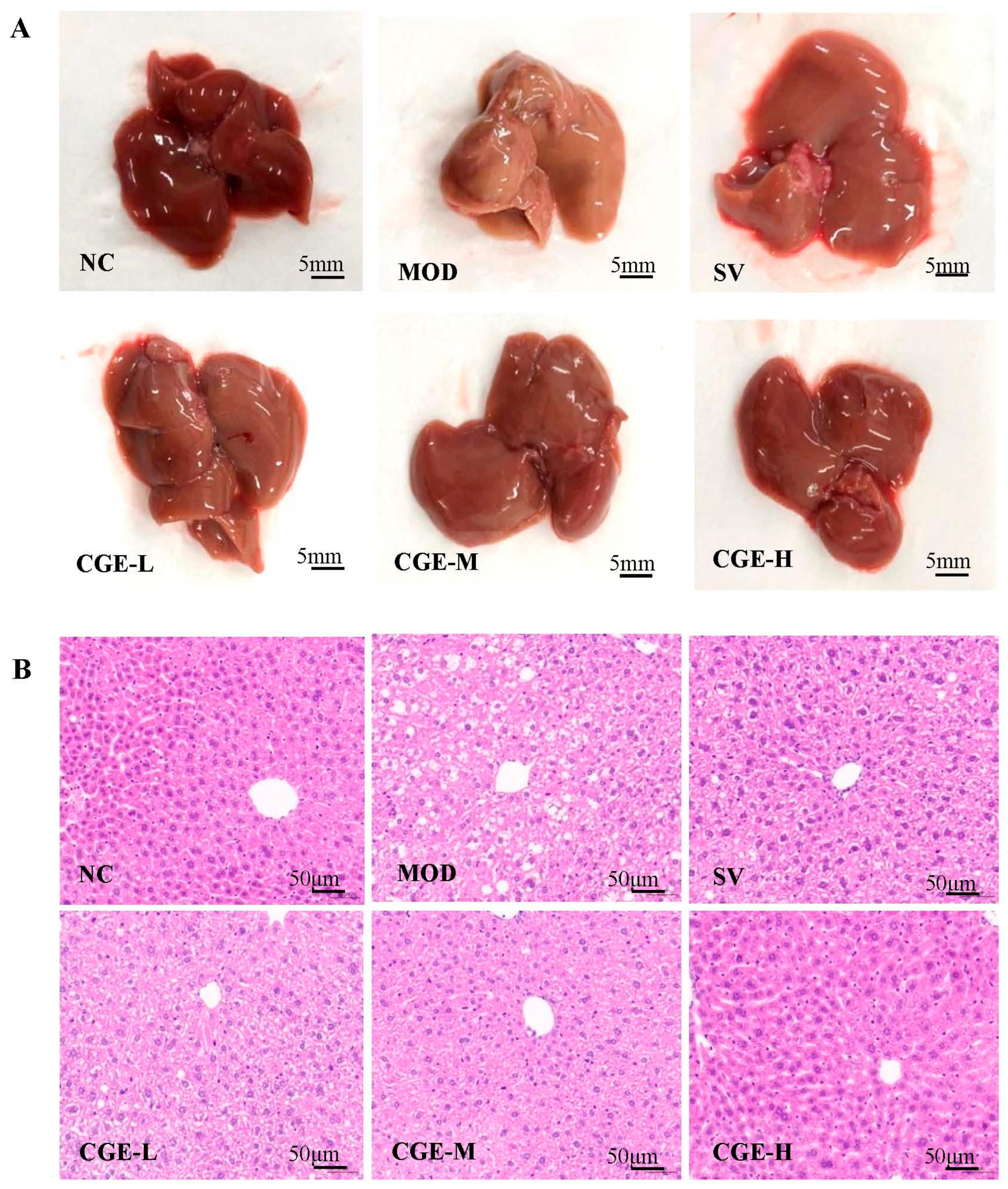

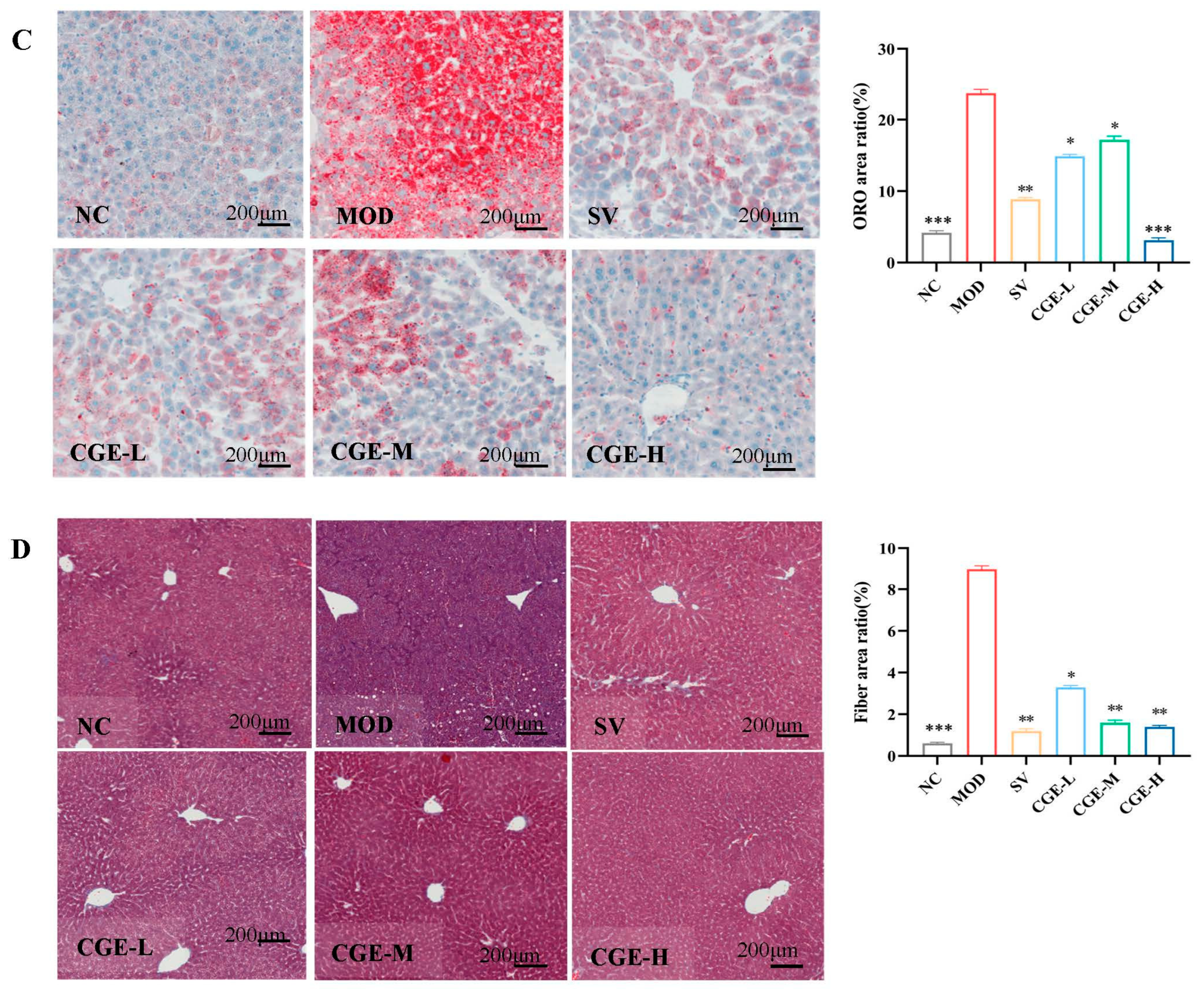

3.5. Pathological Observation of Mouse Livers

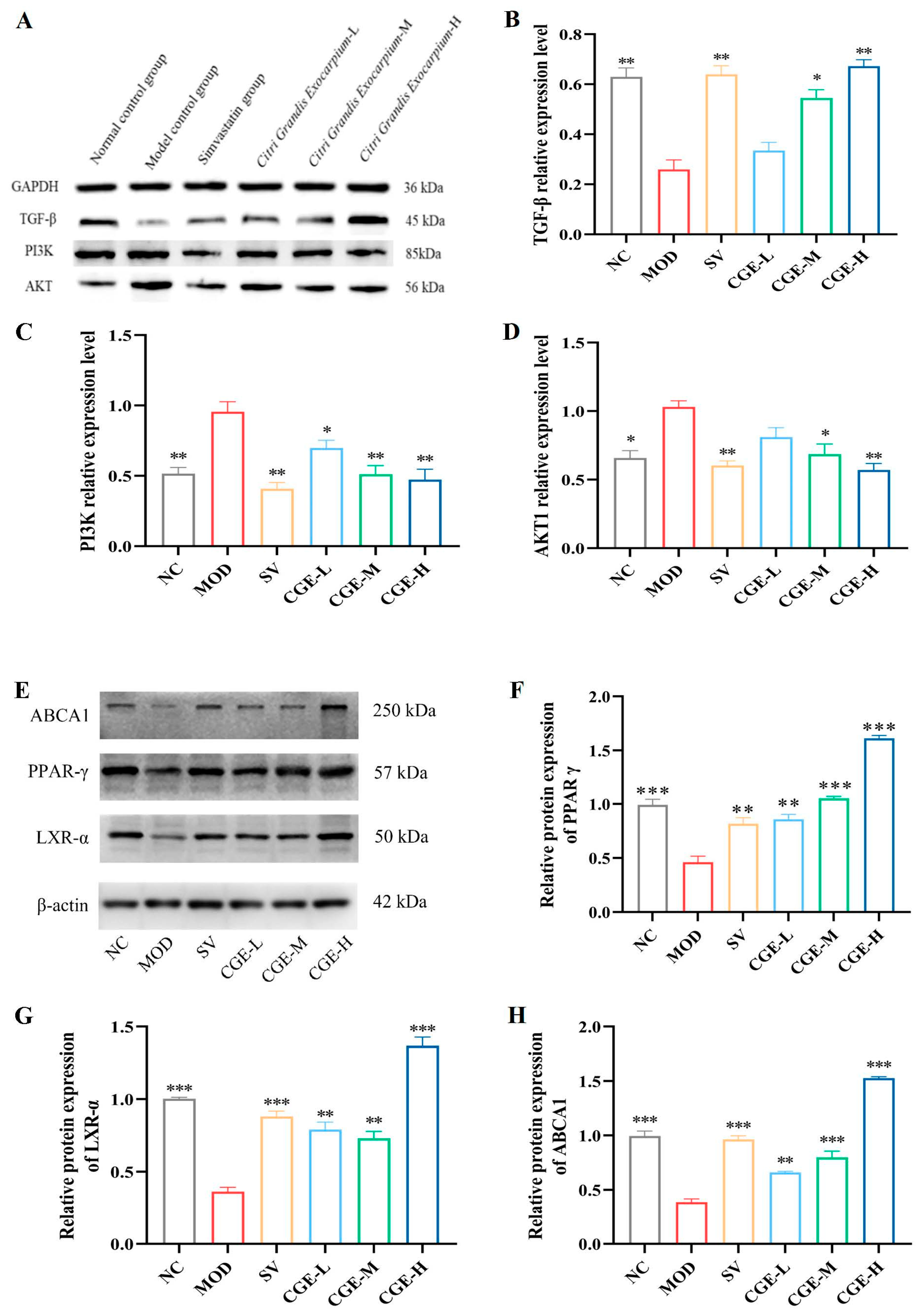

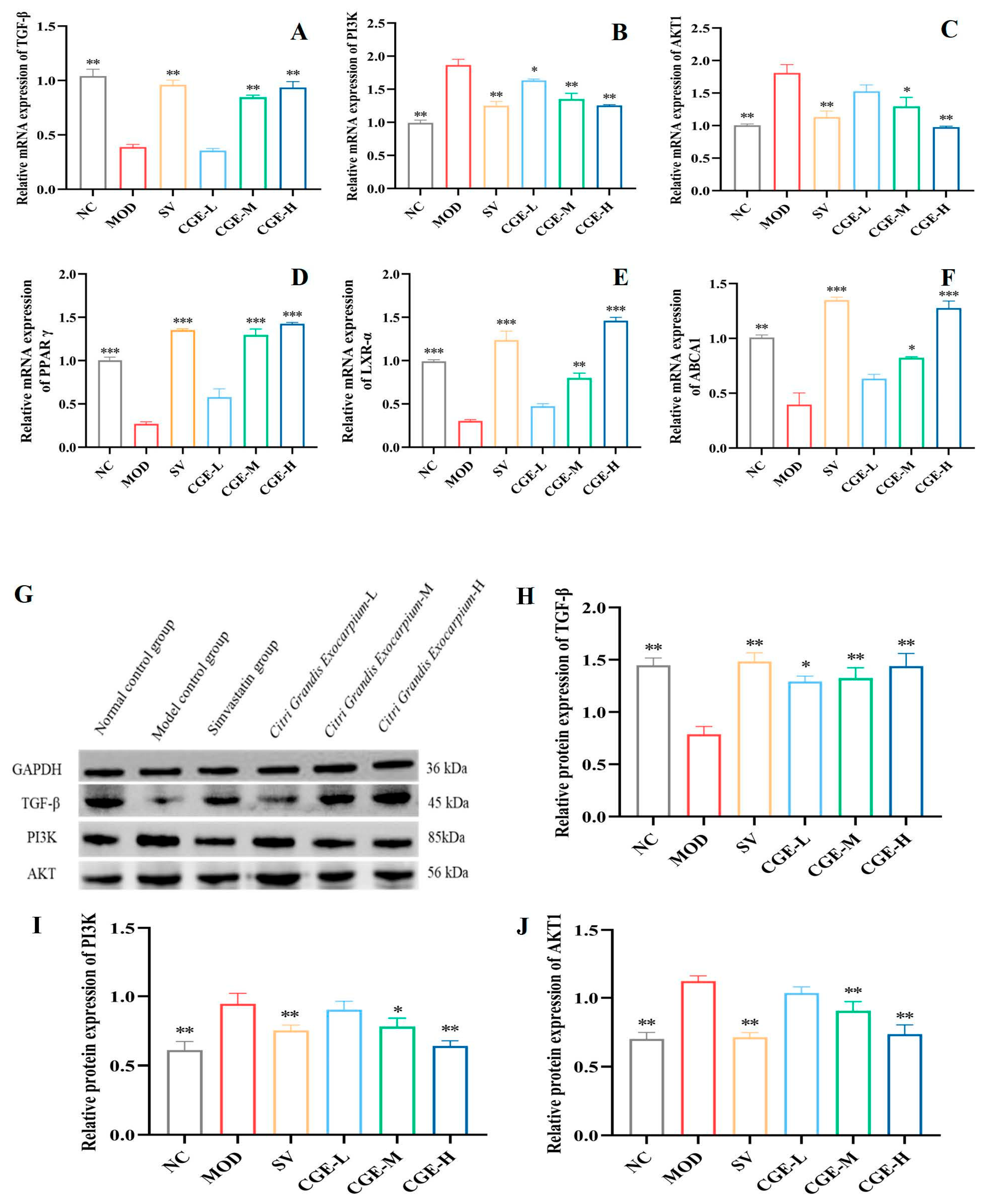

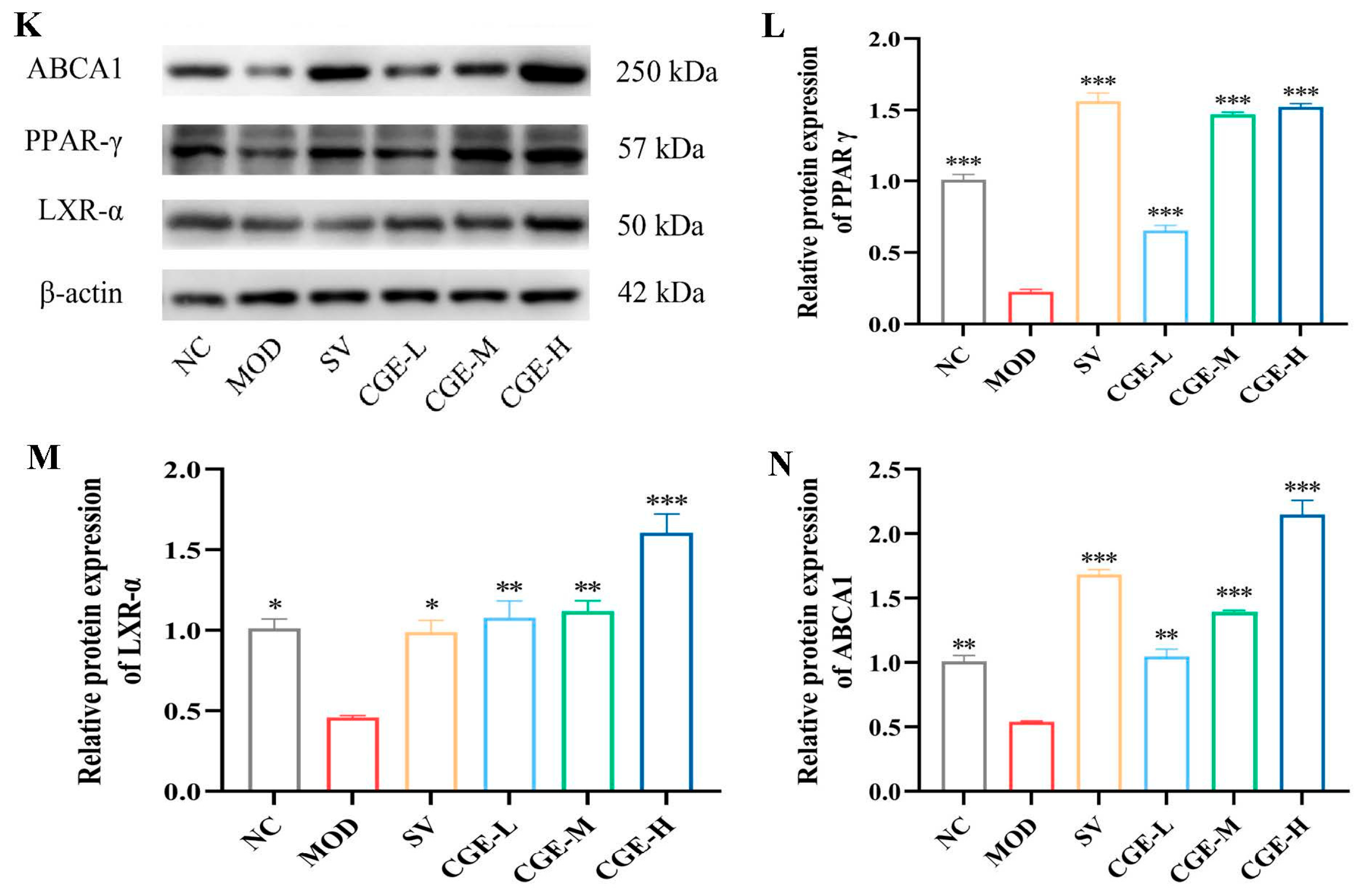

3.6. Protein Expression Levels of TGF-β, PI3K, PPAR-γ, AKT, LXR-α, and ABCA1 in Aortas and Livers of ApoE−/− Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase (GPT) |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase (GOT) |

| AKT1 | Protein kinase B |

| AS | Atherosclerosis |

| ASCVD | Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease |

| apo Al | Apolipoprotein Al |

| apo E | Apolipoprotein E |

| AP | Atherosclerotic plaque |

| ABCA1 | ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic Acid |

| CGE | Citri grandis exocarpium extract |

| CVDs | Cardiovascular diseases |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| HDL-C | High-density lipid cholesterol |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| HUVECs | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial cells |

| HE | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| LXR-α | Liver X receptor Alpha |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LB | Lysis buffer |

| Ldlr | low-density lipoprotein receptor |

| Ox-LDL | Oxidized LDL |

| ORO | Oil red O |

| OD | Optical density |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PAD | Photodiode array detector |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| PPAR-γ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| VSMC | Vascular smooth muscle cell |

References

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. The Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China, 2020th ed.; China Medic Science Press: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, K.; Song, Q.; Wang, L.; Xie, T.; Wu, X.; Wang, P.; Yin, G.; Ye, W.; Wang, T. Antitussive, expectorant and anti-inflammatory activities of different extracts from Exocarpium Citri grandis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 28, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wu, H.; Su, W.; Shi, R.; Li, P.; Liao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, P. Effects of Total Flavonoids from Exocarpium Citri Grandis on Air Pollution Particle-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Mice. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 3843–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.C.; Wu, M.H.; Yu, P.H.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.G.; Xie, C.J.; Cao, H. Herbalogical study on historical evolution of collection, processing and efficacy of Citri Exocarpium Rubrum and Citri Grandis Exocarpium. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2021, 46, 4865–4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Lin, L.; Wei, H.; She, D.; Huang, X.L. HPLC fingerprint of citri grandis exocarpium from different cultivars. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2012, 37, 3092–3096. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, S.; Wang, L.; Lin, L.; Xiao, F.; Shuai, O. Comparison on UPLC and HPLC fingerprints of flavonoids in Citri Grandis Exocarpium. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2013, 44, 1195–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, M.; Wu, H.; Hu, S.; Zhoug, M.; Su, W.; Li, P. Research Progress on Chemical Components, Pharmacological Effects, and Toxicology of Citri Grandis Exocarpium. World Chin. Med. 2024, 19, 3889–3897. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, K.; Bi, Y.; Kong, F. Inclusion Complex of Exocarpium Citri Grandis Essential Oil with beta-Cyclodextrin: Characterization, Stability, and Antioxidant Activity. J. Food Sci. 2019, 4, 1592–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Liu, Q.; Liang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Yu, X.; Yang, D.; Xu, X. The GC/MS Analysis of Volatile Components Extracted by Different Methods from Exocarpium Citri Grandis. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2013, 2013, 918406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, J. Polysaccharides from Exocarpium Citri Grandis: Graded Ethanol Precipitation, Structural Characterization, Inhibition of alpha-Glucosidase Activity, Anti-Oxidation, and Anti-Glycation Potentials. Foods 2025, 4, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Zhang, C.; Xie, L.; Dai, H.; Huang, B.; Wang, X. Determination of Coumarins in Tomentose Pummelo Peel by HPLC. Food Sci. 2009, 30, 320–323. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Lin, L. Study on coumarin compounds from Exocarpium Citri Grandis. Zhong Yao Cai 2004, 7, 577–578. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Chen, Z.; Lin, L.; Wu, Z.; Wu, J. Optimization of Extraction Technology for Inositol from Exocarpium Citri Grandis. J. Guangzhou Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2012, 29, 424–427. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, F.; Deng, S.; Deng, C.; Deng, T.; Lin, L. Content Comparison of Myo-Inositol from Citrus grandis of Different Varieties. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae 2013, 19, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Qian, D.; Duan, J.; Li, X.; Wan, J.; Guo, J. UPLC-Q-TOF-MS analysis of naringin and naringenin and its metabolites in rat plasma after intragastrical administration of alcohol extract of exocarpium Citri grandis. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2010, 5, 1580–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jin, G.; Wang, Y.; Xian, S.; Zhao, J.; Yu, J.; Liu, H.; Tan, Y.; Wen, J.; Xiong, P. Optimization of the Preparation of Exocarpium Citri grandis Extract and Its Lipid Level-lowering Effects. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 40, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, C7–C12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linton, M.F.; Moslehi, J.J.; Babaev, V.R. Akt Signaling in Macrophage Polarization, Survival, and Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagov, A.V.; Markin, A.M.; Bogatyreva, A.I.; Tolstik, T.V.; Sukhorukov, V.N.; Orekhov, A.N. The Role of Macrophages in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Cells 2023, 12, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabas, I.; García-Cardeña, G.; Owens, G.K. Recent insights into the cellar biology of atherosclerosis. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 209, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, M.F.; Babaev, V.R.; Huang, J.; Linton, E.F.; Tao, H.; Yancey, P.G. Macrophage Apoptosis and Efferocytosis in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Circ. J. 2016, 80, 2259–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaev, V.R.; Ding, L.; Zhang, Y.; May, J.M.; Lin, P.C.; Fazio, S.; Linton, M.F. Macrophage IKK alpha Deficiency Suppresses Akt Phosphorylation, Reduces Cell Survival, and Decreases Early Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oram, J.F.; Vaughan, A.M. ABCA1-mediated transport of cellular cholesterol and phospholipids to HDL apolipoproteins. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2000, 11, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savla, S.R.; Prabhavalkar, K.S.; Bhatt, L.K. Liver X receptor: A potential target in the treatment of atherosclerosis. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2022, 26, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed.; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Catta-Preta, M.; Mendonca, L.S.; Fraulob-Aquino, J.; Aguila, M.B.; Mandarim-de-Lacerda, C.A. A critical analysis of three quantitative methods of assessment of hepatic steatosis in liver biopsies. Virchows Arch. 2011, 459, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Zacarías, J.L.; Castro-Muñozledo, F.; Kuri-Harcuch, W. Quantitation of adipose conversion and triglycerides by staining intracytoplasmic lipids with Oil red, O. Histochemistry 1992, 97, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawien, J. The role of an experimental model of atherosclerosis: ApoE-knockout mice in developing new drug against atherosclerosis. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2012, 13, 2435–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Y.; Qin, L.F.; Michael, S. Imaging and Analysis of Oil Red O-Stained Whole Aorta Lesions in an Aneurysm Hyperlipidemia Mouse Model. J. Vis. Exp. 2022, 183, 10.3791/61277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Y.; Qin, L.; Li, G.; Wang, Z.; Dahlman, J.E.; Malagon-Lopez, J.; Gujja, S.; Cilfone, N.A.; Kauffman, K.J.; Sun, L.; et al. Endothelial TGF-β signaling drives vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 912–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, A.; Boisvert, W.A.; Lee, C.H.; Laffitte, B.A.; Barak, Y.; Joseph, S.B.; Liao, D.; Nagy, L.; Edwards, P.A.; Curtiss, L.K.; et al. A PPARγ-LXR-ABCA1 Pathway in macrophages is involved in cholesterol efflux and atherogenesis. Mol. Cell 2001, 7, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Watanabe, T. Atherosclerosis: Known and unknown. Pathol. Int. 2022, 72, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Rosamond, W.; Flegal, K.; Furie, K.; Go, A.; Greenlund, K.; Haase, N.; Hailpern, S.M.; Ho, M.; Howard, V.; Kissela, B.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2008, 117, e25–e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, I.E.; Mejevoi, N.; Anichkov, N.M. Nikolai N. Anichkov and his theory of atherosclerosis. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2006, 33, 417–423. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Watanabe, T. Inflammatory reactions in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2003, 10, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, T.J. Macrophages in atherosclerosis regression. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italiani, P.; Boraschi, D. From monocytes to M1/M2 macrophages: Phenotypical vs. functional differentiation. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swirski Filip, K.; Robbins Clinton, S.; Matthias, N. Development and function of arterial and cardiac macrophages. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, S.-M.; Saeed, M.; Hossein, V.; Mahdi, T.; Seyed-Alireza, E.E.; Fatemeh, M.; Bita, S.; Asadollah, M.; Afshari, J.T.; Sahebkar, A. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 6425–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergadi, E.; Ieronymaki, E.; Lyroni, K.; Vaporidi, K.; Tsatsanis, C. Akt Signaling Pathway in Macrophage Activation and M1/M2 Polarization. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawień, J.; Nastałek, P.; Korbut, R. Mouse models of experimental atherosclerosis. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2004, 55, 503–517. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, C.G.; Wang, X.H.; Liu, D.H. Progression of atherosclerosis in ApoE-knockout mice fed on a high-fat diet. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 3863–3867. [Google Scholar]

- Bobik, A.; Agrotis, A.; Kanellakis, P.; Dilley, R.; Krushinsky, A.; Smirnov, V.; Tararak, E.; Condron, M.; Kostolias, G. Distinct patterns of transforming growth factor-beta isoform and receptor expression in human atherosclerotic lesions. Colocalization implicates TGF-beta in fibrofatty lesion development. Circulation 1999, 99, 2883–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goumans, M.J.; Ten Dijke, P. TGF-beta signaling in control of cardiovascular function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a022210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañares, C.; Redondo-Horcajo, M.; Magán-Marchal, N.; Dijke, P.T.; Lamas, S.; Rodríguez-Pascual, F. Signaling by ALK5 mediates TGF-beta-induced ET-1 expression in endothelial cells: A role for migration and proliferation. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120 Pt. 7, 1256–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzola, M.; Page, C.; Rogliani, P.; Calzetta, L.; Matera, M.G. PI3K Inhibitors as Potential Therapeutic Agents for the Treatment of COPD with Associated Atherosclerosis. Drugs 2025, 85, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalata, T.; Deleanu, M.; Carnuta, M.G.; Niculescu, L.S.; Raileanu, M.; Sima, A.V.; Stancu, C.S. Hyperlipidemia Determines Dysfunctional HDL Production and Impedes Cholesterol Efflux in the Small Intestine: Alleviation by Ginger Extract. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1900029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barish, G.D. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors and Liver X Receptors in Atherosclerosis and Immunity. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yvan Charvet, L.; Ranalletta, M.; Wang, N.; Han, S.; Terasaka, N.; Li, R.; Welch, C.; Tall, A.R. Combined deficiency of ABCA1 and ABCG1 promotes foam cell accumulation and accelerates atherosclerosis in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 3900–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer Name | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) | Product Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| TGF-β1-F | TGGCCAGATCCTGTCCAAAC | 97 |

| TGF-β1-R | GTTGTACAAAGCGAGCACCG | 97 |

| PI3K-F | GGGACTTTGGAGACCAGAAGG | 108 |

| PI3K-R | GTGTCTGGGTTCACCACACC | 108 |

| AKT1- F | AGTCCCCACTCAACAACTTCT | 119 |

| AKT1-R | GAAGGTGCGCTCAATGACTG | 119 |

| PPAR-γ-F | GCAGCTACTGCATGTGATCAAGA | 107 |

| PPAR-γ-R | GTCAGCGGGTGGGACTTTC | 107 |

| ABCA1-F | GAGCAAAGCCAAGCATCTTC | 172 |

| ABCA1-R | TAGAACGGGCAGGTTGGTAG | 172 |

| LXR-α-F | AGGAGTGTCGACTTCGCAAA | 101 |

| LXR-α-R | CTCTTCTTGCCGCTTCAGTTT | 101 |

| GAPDH-F | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG | 123 |

| GAPDH-R | TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA | 123 |

| β-actin-F | GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG | 154 |

| β-actin-R | CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT | 154 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Wen, W.-Z.; Zhao, J.-H.; Guo, J.-R.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Xiong, P. Citri grandis Exocarpium Extract Alleviates Atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− Mice by Modulating the Expression of TGF-β1, PI3K, AKT1, PPAR-γ, LXR-α, and ABCA1. Foods 2025, 14, 4267. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244267

Xu J, Wen W-Z, Zhao J-H, Guo J-R, Zhang Z-Y, Xiong P. Citri grandis Exocarpium Extract Alleviates Atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− Mice by Modulating the Expression of TGF-β1, PI3K, AKT1, PPAR-γ, LXR-α, and ABCA1. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4267. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244267

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jing, Wen-Zhao Wen, Jun-Hui Zhao, Jun-Rong Guo, Zhuo-Ya Zhang, and Ping Xiong. 2025. "Citri grandis Exocarpium Extract Alleviates Atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− Mice by Modulating the Expression of TGF-β1, PI3K, AKT1, PPAR-γ, LXR-α, and ABCA1" Foods 14, no. 24: 4267. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244267

APA StyleXu, J., Wen, W.-Z., Zhao, J.-H., Guo, J.-R., Zhang, Z.-Y., & Xiong, P. (2025). Citri grandis Exocarpium Extract Alleviates Atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− Mice by Modulating the Expression of TGF-β1, PI3K, AKT1, PPAR-γ, LXR-α, and ABCA1. Foods, 14(24), 4267. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244267