Incorporating Cricket Powder into Salad Dressing: Enhancing Protein Content and Functional Attributes Through Partial Palm-Oil Replacement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Salad Dressing Preparation

2.3. pH and Color

2.4. Emulsion Stability (ES)

2.5. Rheological Properties

2.6. Microstructure

2.7. Assessment of TPC, TFC, and Antioxidant Capacity

2.7.1. Sample Preparation and Extraction

2.7.2. Determination of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.7.3. Assessment of Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

2.7.4. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Assay

2.7.5. FRAP-Based Determination of Antioxidant Capacity

2.8. Determination of Free Fatty Acid and Acid Value

2.9. E-Nose

2.10. E-Tongue

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Physical Characteristics of Salad Dressing

3.2. Emulsion Stability

3.3. Free Fatty Acid (FFA) Content

3.4. Viscosity

3.5. Analysis of Rheological Models

3.6. Frequency Sweep Tests

3.7. Microstructural Characteristics of Salad Dressings Under Microscopy

3.8. Antioxidant Properties of Salad Dressing

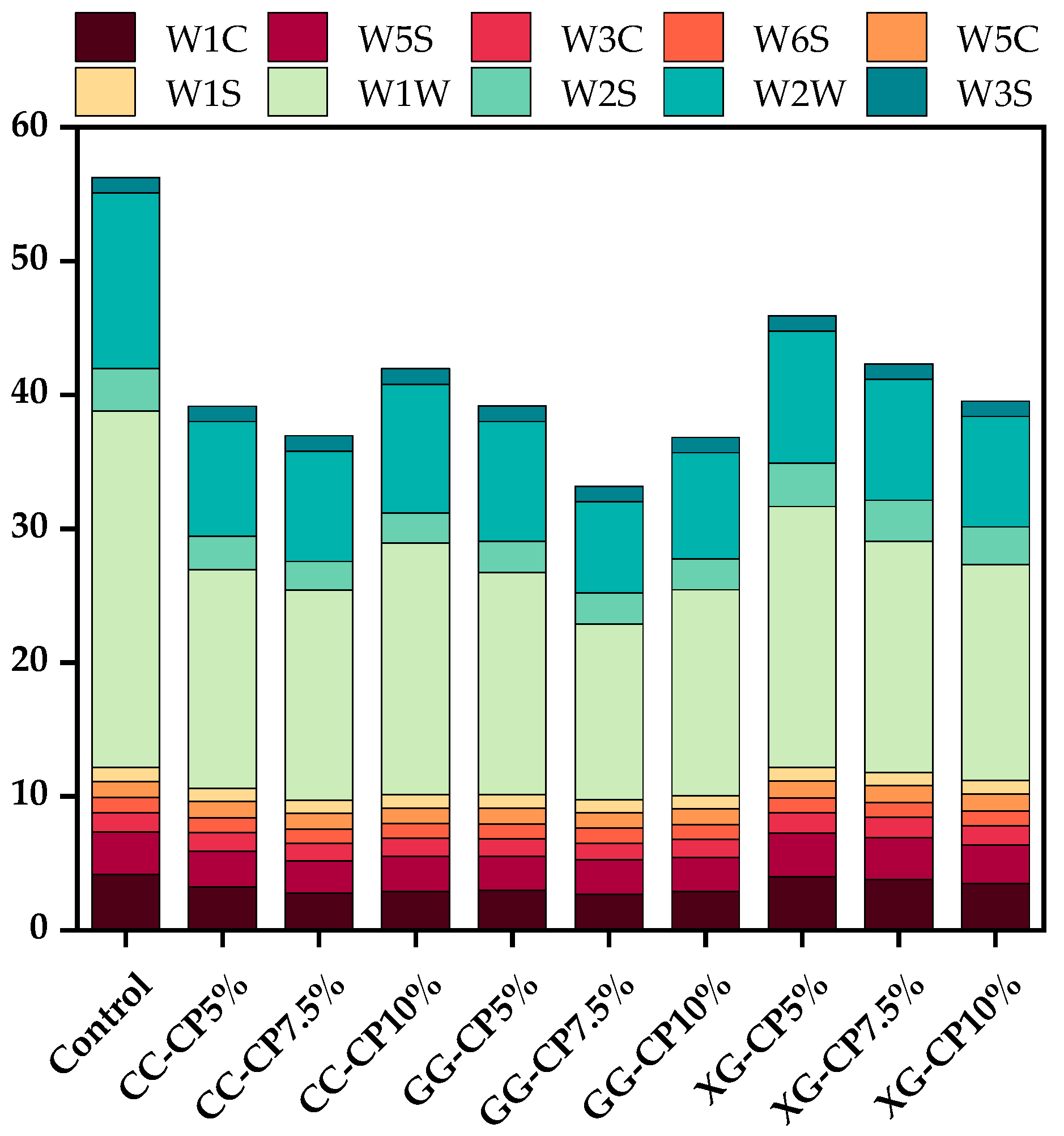

3.9. E-Nose

3.10. E-Tongue

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tekin-Cakmak, Z.H.; Atik, I.; Karasu, S. The Potential Use of Cold-Pressed Pumpkin Seed Oil By-Products in a Low-Fat Salad Dressing: The Effect on Rheological, Microstructural, Recoverable Properties, and Emulsion and Oxidative Stability. Foods 2021, 10, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Chen, M.; Yanagisawa, T.; Matsuoka, R.; Xi, Y.; Tao, N.; Wang, X. Physical properties, chemical composition, and nutritional evaluation of common salad dressings. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 978648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Quek, S.Y.; Lam, G.; Easteal, A.J. The rheological behaviour of low fat soy-based salad dressing. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 2204–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaili, T.M.; Hasan, F.; Al-Nabulsi, A.A.; Olaimat, A.N.; Ayyash, M.; Obaid, R.S.; Holley, R. A worldwide review of illness outbreaks involving mixed salads/dressings and factors influencing product safety and shelf life. Food Microbiol. 2023, 112, 104238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Liu, R.; Liang, B.; Wu, T.; Sui, W.; Zhang, M. Microparticulated whey protein-pectin complex: A texture-controllable gel for low-fat mayonnaise. Food Res. Int. 2018, 108, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcicek, A.; Yildirim, R.M.; Tekin-Cakmak, Z.H.; Karasu, S. Low-Fat Salad Dressing as a Potential Probiotic Food Carrier Enriched by Cold-Pressed Tomato Seed Oil By-Product: Rheological Properties, Emulsion Stability, and Oxidative Stability. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 48520–48530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, I.; Šoronja-Simović, D.; Zahorec, J.; Dokić, L.; Lončarević, I.; Stožinić, M.; Petrović, J. Polysaccharide-Based Fat Replacers in the Functional Food Products. Processes 2024, 12, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Setyabrata, D.; Lee, Y.; Jones, O.G.; Kim, Y.H.B. Effect of House Cricket (Acheta domesticus) Flour Addition on Physicochemical and Textural Properties of Meat Emulsion Under Various Formulations. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 2787–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aidoo, O.F.; Osei-Owusu, J.; Asante, K.; Dofuor, A.K.; Boateng, B.O.; Debrah, S.K.; Ninsin, K.D.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Chia, S.Y. Insects as food and medicine: A sustainable solution for global health and environmental challenges. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1113219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonarsa, P.; Bunyatratchata, A.; Phuseerit, O.; Phonphan, N.; Chumroenphat, T.; Dechakhamphu, A.; Thammapat, P.; Katisart, T.; Siriamornpun, S. Quality variation of house cricket (Acheta domesticus) powder from Thai farms: Chemical composition, micronutrients, bioactive compounds, and microbiological safety. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantzen Da Silva Lucas, A.; Menegon De Oliveira, L.; Da Rocha, M.; Prentice, C. Edible insects: An alternative of nutritional, functional and bioactive compounds. Food Chem. 2020, 311, 126022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnjanapratum, S.; Kaewthong, P.; Indriani, S.; Petsong, K.; Takeungwongtrakul, S. Characteristics and nutritional value of silkworm (Bombyx mori) pupae-fortified chicken bread spread. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, R.; Liang, H. Food Hydrocolloids: Structure, Properties, and Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabeen, F.; Zil-e-Aimen; Ahmad, R.; Mir, S.; Awwad, N.S.; Ibrahium, H.A. Carrageenan: Structure, properties and applications with special emphasis on food science. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 22035–22062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahmouzi, S.; Meftahizadeh, H.; Eyshi, S.; Mahmoudzadeh, A.; Alizadeh, B.; Mollakhalili-Meybodi, N.; Hatami, M. Application of guar (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L.) gum in food technologies: A review of properties and mechanisms of action. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 4869–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocan, P.; Ilhan, E.; Oztop, M.H. Characterization of Emulsion Stabilization Properties of Gum Tragacanth, Xanthan Gum and Sucrose Monopalmitate: A Comparative Study. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 1087–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribes, S.; Fuentes, A.; Barat, J.M. Physical stability, rheology and microstructure of salad dressing containing essential oils: Study of incorporating nanoemulsions. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 1626–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpizar-Reyes, E.; Carrillo-Navas, H.; Gallardo-Rivera, R.; Varela-Guerrero, V.; Alvarez-Ramirez, J.; Pérez-Alonso, C. Functional properties and physicochemical characteristics of tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) seed mucilage powder as a novel hydrocolloid. J. Food Eng. 2017, 209, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, E.; Tekin-Cakmak, Z.H.; Ozgolet, M.; Karasu, S.; Kasapoglu, M.Z.; Ramadan, M.F.; Sagdic, O. Capsaicin Rich Low-Fat Salad Dressing: Improvement of Rheological and Sensory Properties and Emulsion and Oxidative Stability. Foods 2023, 12, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsuwan, S. Effect of Inulin on Rheological Properties and Emulsion Stability of a Reduced-Fat Salad Dressing. Int. J. Food Sci. 2024, 2024, 4229514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelled, A.; Fernandes, Â.; Barros, L.; Chahdoura, H.; Achour, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Cheikh, H.B. Chemical and antioxidant parameters of dried forms of ginger rhizomes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 77, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratseewo, J.; Warren, F.J.; Siriamornpun, S. The influence of starch structure and anthocyanin content on the digestibility of Thai pigmented rice. Food Chem. 2019, 298, 124949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molole, G.J.; Gure, A.; Abdissa, N. Determination of total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of Commiphora mollis (Oliv.) Engl. resin. BMC Chem. 2022, 16, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriamornpun, S.; Kaewseejan, N. Quality, bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of selected climacteric fruits with relation to their maturity. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 221, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butsat, S.; Siriamornpun, S. Antioxidant capacities and phenolic compounds of the husk, bran and endosperm of Thai rice. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriamornpun, S.; Tangkhawanit, E.; Kaewseejan, N. Reducing retrogradation and lipid oxidation of normal and glutinous rice flours by adding mango peel powder. Food Chem. 2016, 201, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.R.; Junarto, A.W.; Benjakul, S.; Mittal, A.; Baloch, K.A.; Singh, A. Omega-3 and unsaturated fatty acid enrichment of shrimp oil: Preparation, characterization, and its application in salad dressings. LWT 2024, 212, 116993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Gooneratne, R.; Li, J. Comparative Analysis of Flavor, Taste, and Volatile Organic Compounds in Opossum Shrimp Paste during Long-Term Natural Fermentation Using E-Nose, E-Tongue, and HS-SPME-GC-MS. Foods 2022, 11, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, T.; Hai, N.; Guo, P.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, Z.; Liu, H.; Ding, L. Characteristics of Umami Taste of Soy Sauce Using Electronic Tongue, Amino Acid Analyzer, and MALDI−TOF MS. Foods 2024, 13, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combrzyński, M.; Oniszczuk, T.; Wójtowicz, A.; Biernacka, B.; Wojtunik-Kulesza, K.; Bąkowski, M.; Różyło, R.; Szponar, J.; Soja, J.; Oniszczuk, A. Nutritional Characteristics of New Generation Extruded Snack Pellets with Edible Cricket Flour Processed at Various Extrusion Conditions. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkusz, A.; Orkusz, M. Effect of Acheta domesticus Powder Incorporation on Nutritional Composition, Technological Properties, and Sensory Acceptance of Wheat Bread. Insects 2025, 16, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Seephua, N.; Prakitchaiwattana, C.; Liu, R.-X.; Zheng, J.-S.; Siriamornpun, S. Fortification of cricket and silkworm pupae powders to improve nutritional quality and digestibility of rice noodles. Food Chem. X 2025, 26, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielińska, E.; Pankiewicz, U.; Sujka, M. Nutritional, Physiochemical, and Biological Value of Muffins Enriched with Edible Insects Flour. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, E. Hydrocolloids at interfaces and the influence on the properties of dispersed systems. Food Hydrocoll. 2003, 17, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, A.; Cho, Y.-H.; Kim, Y.H.B.; Jones, O.G. Contributions of protein and milled chitin extracted from domestic cricket powder to emulsion stabilization. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2019, 1, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linlaud, N.; Ferrer, E.; Puppo, M.C.; Ferrero, C. Hydrocolloid Interaction with Water, Protein, and Starch in Wheat Dough. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiang, D. Effect of Coconut Protein and Xanthan Gum, Soybean Polysaccharide and Gelatin Interactions in Oil-Water Interface. Molecules 2022, 27, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immawan, M.A.; Ratnawaty, G.J.; Djohan, H.; Imami, A.D. Effect of Activation Duration of Water Hyacinth-Based Activated Carbon Using Bilimbi (Averrhoa bilimbi) as an Activator on Free Fatty Acid Content in Crude Palm Oil (CPO). Public Health Front. 2025, 1, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangsrianugul, N.; Winuprasith, T.; Suphantharika, M.; Wongkongkatep, J. Effect of hydrocolloids on physicochemical properties, stability, and digestibility of Pickering emulsions stabilized by nanofibrillated cellulose. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimunić-Mežnarić, V.; Vincek, V.; Vincek, D.; Makovec, M. Chemical indicators of the quality of Varaždin pumpkin seed oil. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 15, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, D.; Macedo, G.A.; Luccas, V.; Macedo, J.A. Enzymatic Interesterification: An Innovative Strategy for Lower-Calorie Lipid Production From Refined Peanut Oil. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Mao, X.; Han, H.; Wang, S.; Lei, X.; Li, Y.; Ren, Y. Effect of chitosan and its derivatives on food processing properties of potato starch gel: Based on molecular interactions. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 159, 110596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, T.; Iqbal, M.W.; Jiang, B.; Chen, J. A review of the enzymatic, physical, and chemical modification techniques of xanthan gum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 186, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Roy, S.; Devra, A.; Dhiman, A.; Prabhakar, P.K. Ultrasonication of mayonnaise formulated with xanthan and guar gums: Rheological modeling, effects on optical properties and emulsion stability. LWT 2021, 149, 111632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Song, Z.; Tan, C.; Li, G.; Yu, D.; Liu, W. AKD Emulsions Stabilized by Guar Gel: A Highly Efficient Agent to Improve the Hydrophobicity of Cellulose Paper. Polymers 2023, 15, 4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; McClements, D.J. Design of reduced-fat food emulsions: Manipulating microstructure and rheology through controlled aggregation of colloidal particles and biopolymers. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonarsa, P.; Bunyatratchata, A.; Chumroenphat, T.; Thammapat, P.; Chaikwang, T.; Siripan, T.; Li, H.; Siriamornpun, S. Nutritional Quality, Functional Properties, and Biological Characterization of Watermeal (Wolffia globosa). Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.H. Potential Synergy of Phytochemicals in Cancer Prevention: Mechanism of Action. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 3479–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, M.; Armendariz, M.; Wagner, J.; Risso, P. Effect of Xanthan Gum on the Rheological Behavior and Microstructure of Sodium Caseinate Acid Gels. Gels 2016, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zou, P.; Cheng, G.; Zhou, J.; Cai, S. Effects of Different Oligochitosans on Isoflavone Metabolites, Antioxidant Activity, and Isoflavone Biosynthetic Genes in Soybean (Glycine max) Seeds during Germination. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 4652–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, H.; Cao, Z.; Yan, J.; Dong, Z.; Ren, F.; Zhang, W.; Chen, L. The Aroma, Taste Contributions, and Flavor Evaluation Based on GC-IMS, E-Nose, and E-Tongue in Soybean Pastes: A Comparative Study. Foods 2025, 14, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpf, J.; Burger, R.; Schulze, M. Statistical evaluation of DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and Folin-Ciocalteu assays to assess the antioxidant capacity of lignins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Yu, X.; Maninder, M.; Xu, B. Total phenolics and antioxidants profiles of commonly consumed edible flowers in China. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 1524–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bungthong, C.; Siriamornpun, S. Changes in Amino Acid Profiles and Bioactive Compounds of Thai Silk Cocoons as Affected by Water Extraction. Molecules 2021, 26, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, P.; Chaowiwat, P.; Weston, J.; Hansawasdi, C. Studies on Microbial Quality, Protein Yield, and Antioxidant Properties of Some Frozen Edible Insects. Int. J. Food Sci. 2021, 2021, 5580976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anuduang, A.; Loo, Y.Y.; Jomduang, S.; Lim, S.J.; Wan Mustapha, W.A. Effect of Thermal Processing on Physico-Chemical and Antioxidant Properties in Mulberry Silkworm (Bombyx mori L.) Powder. Foods 2020, 9, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.; Chen, G.; Liu, H. Antioxidative Categorization of Twenty Amino Acids Based on Experimental Evaluation. Molecules 2017, 22, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Estrada, M.D.L.L.; Aguirre-Becerra, H.; Feregrino-Pérez, A.A. Bioactive compounds and biological activity in edible insects: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Peng, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, Y. Decoding the dynamic evolution of volatile organic compounds of dark tea during solid-state fermentation with Debaryomyces hansenii using HS-SPME-GC/MS, E-nose and transcriptomic analysis. LWT 2025, 223, 117765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani Gorji, S.; Calingacion, M.; Smyth, H.E.; Fitzgerald, M. Comprehensive profiling of lipid oxidation volatile compounds during storage of mayonnaise. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 4076–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Song, J.; Chen, S.; Fu, C.; Li, Z.; Weng, W.; Shi, L.; Ren, Z. Improving surimi gel quality by corn oligopeptide-chitosan stabilized high-internal phase Pickering emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 166, 111268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yao, W.; Ma, S.; Liu, D.; Zhang, M. Evolution of key flavor compounds in sonit sheep lamb during grilling process using HS-GC-IMS, E-nose, E-tongue, and physicochemical techniques. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2025, 40, 101158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Palm Oil | Cricket Powder (CP) | Carrageenan (CC) | Guar Gum (GG) | Xanthan Gum (XG) | Other Ingredients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 32.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Water (52.5% w/w) vinegar (10% w/w), egg yolk (3% w/w), sugar (1% w/w), salt (0.5% w/w) and citric acid (0.5% w/w) |

| CC-CP5% | 27.5 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| CC-CP7.5% | 25 | 7.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| CC-CP10% | 22.5 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| GG-CP5% | 27.5 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| GG-CP7.5% | 25 | 7.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| GG-CP10% | 22.5 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| XG-CP5% | 27.5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| XG-CP7.5% | 25 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| XG-CP10% | 22.5 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sensor Number | Sensor Name | Sensitive Substance |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | W1C | Aromatic components |

| 2 | W5S | Nitrogen oxides |

| 3 | W3C | Aromatic and ammonia components |

| 4 | W6S | Hydrides |

| 5 | W5C | Aromatic components (short-chain alkanes) |

| 6 | W1S | Methyl compounds |

| 7 | W1W | Inorganic sulfides |

| 8 | W2S | Alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones |

| 9 | W2W | Aromatic components (organic sulfides) |

| 10 | W3S | Long-chain alkanes |

| Treatment | pH | Color | ES (%) | FFA (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | ||||

| Control | 3.32 ± 0.00 I | 72.84 ± 2.50 a | −1.81 ± 0.30 f | 14.93 ± 1.67 d | 78.58 ± 2.90 a | 6.31 ± 0.51 cde |

| CC-CP5% | 3.88 ± 0.01 g | 60.42 ± 0.76 b | 2.38 ± 0.12 c | 16.40 ± 2.05 cd | 46.91 ± 0.84 d | 6.99 ± 0.28 bc |

| CC-CP7.5% | 4.05 ± 0.00 d | 56.23 ± 0.80 def | 3.06 ± 0.12 ab | 19.16 ± 0.59 a | 52.39 ± 0.23 c | 8.10 ± 0.69 a |

| CC-CP10% | 4.25 ± 0.01 a | 55.56 ± 0.30 ef | 2.88 ± 0.03 b | 17.29 ± 1.05 bc | 53.34 ± 0.38 c | 7.55 ± 0.08 ab |

| GG-CP5% | 3.77 ± 0.00 h | 60.34 ± 0.64 b | 2.02 ± 0.29 d | 18.54 ± 1.09 ab | 79.00 ± 3.25 a | 6.05 ± 0.21 de |

| GG-CP7.5% | 3.93 ± 0.01 f | 60.13 ± 0.26 b | 2.79 ± 0.07 b | 16.27 ± 0.01 cd | 82.00 ± 1.67 a | 6.13 ± 0.29 cde |

| GG-CP10% | 4.19 ± 0.00 b | 54.86 ± 0.14 f | 3.29 ± 0.04 a | 15.91 ± 0.03 cd | 81.94 ± 2.27 a | 6.86 ± 0.65 bcd |

| XG-CP5% | 3.96 ± 0.00 e | 58.12 ± 0.80 c | 1.67 ± 0.01 e | 11.18 ± 0.39 e | 53.42 ± 2.12 c | 5.59 ± 0.25 e |

| XG-CP7.5% | 3.95 ± 0.00 e | 56.65 ± 0.52 cde | 2.78 ± 0.16 b | 18.51 ± 0.08 ab | 59.98 ± 1.81 b | 5.4 ± 0.05 e |

| XG-CP10% | 4.12 ± 0.00 c | 57.59 ± 0.05 cd | 2.85 ± 0.01 b | 16.22 ± 0.29 cd | 61.82 ± 0.83 b | 5.42 ± 0.08 e |

| Treatment | Power Law Model | Herschel–Bulckley Model | Casson Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KP (Pa.sn) | nP | R2 | τ0H (Pa) | KH (Pa.s) | nH | R2 | τC (Pa.s0.5) | nC | R2 | |

| Control | 2.69 ± 0.05 j | 0.28 ± 0.01 de | 0.9948 | 2.40 ± 0.06 i | 0.95 ± 0.01 i | 0.43 ± 0.03 e | 0.9997 | 3.47 ± 0.04 j | 0.02 ± 0.00 i | 0.9927 |

| CC-CP5% | 4.03 ± 0.02 i | 0.42 ± 0.01 b | 0.9873 | 5.37 ± 0.02 h | 4.46 ± 0.03 f | 0.61 ± 0.02 c | 0.9978 | 6.62 ± 0.02 h | 0.04 ± 0.00 h | 0.9332 |

| CC-CP7.5% | 7.51 ± 0.04 g | 0.27 ± 0.01 e | 0.9867 | 14.28 ± 0.02 f | 15.40 ± 0.01 c | 0.53 ± 0.01 d | 0.9988 | 9.77 ± 0.02 g | 0.05 ± 0.00 g | 0.9538 |

| CC-CP10% | 12.21 ± 0.07 e | 0.29 ± 0.01 d | 0.9542 | 42.94 ± 0.01 c | 70.43 ± 0.07 a | 0.32 ± 0.01 g | 0.9987 | 15.89 ± 0.03 e | 0.06 ± 0.00 f | 0.8915 |

| GG-CP5% | 4.20 ± 0.03 h | 0.60 ± 0.01 a | 0.9998 | 0.64 ± 0.04 j | 3.65 ± 0.05 g | 0.63 ± 0.03 c | 1 | 5.70 ± 0.02 i | 0.29 ± 0.01 b | 0.9953 |

| GG-CP7.5% | 10.80 ± 0.10 f | 0.38 ± 0.01 c | 0.9898 | 5.67 ± 0.05 h | 7.64 ± 0.11 e | 0.54 ± 0.01 d | 0.9996 | 15.12 ± 0.02 f | 0.36 ± 0.01 a | 0.9898 |

| GG-CP10% | 23.98 ± 0.01 c | 0.30 ± 0.02 d | 0.9748 | 45.36 ± 0.03 a | 10.44 ± 0.10 d | 0.38 ± 0.01 f | 0.9850 | 30.42 ± 0.02 c | 0.13 ± 0.01 c | 0.9778 |

| XG-CP5% | 17.10 ± 0.08 d | 0.27 ± 0.01 e | 0.9736 | 33.90 ± 0.04 e | 0.01 ± 0.00 j | 0.98 ± 0.01 a | 0.9968 | 21.43 ± 0.03 d | 0.09 ± 0.00 d | 0.9790 |

| XG-CP7.5% | 24.82 ± 0.0 b | 0.21 ± 0.02 f | 0.9857 | 35.26 ± 0.07 d | 1.28 ± 0.05 h | 0.68 ± 0.01 b | 0.9964 | 30.19 ± 0.04 b | 0.07 ± 0.00 e | 0.9600 |

| XG-CP10% | 37.28 ± 0.27 a | 0.15 ± 0.01 g | 0.9458 | 44.85 ± 0.15 b | 20.94 ± 0.06 b | 0.16 ± 0.01 h | 0.9961 | 43.11 ± 0.02 a | 0.06 ± 0.00 f | 0.9250 |

| Treatment | TPC (mg GAE/ 100 g FW) | TFC (mg QE/ 100 g FW) | FRAP (mg FeSO4/100 g FW) | DPPH (mg Vitamin C/ 100 g FW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 37.05 ± 1.68 i | 60.09 ± 5.72 f | 39.38 ± 1.52 e | 2.75 ± 0.36 g |

| CC-CP5% | 65.39 ± 0.13 f | 211.79 ± 14.25 b | 67.61 ± 0.20 c | 19.27 ± 0.05 d |

| CC-CP7.5% | 71.75 ± 0.70 d | 219.72 ± 9.23 b | 69.56 ± 0.19 c | 18.81 ± 0.02 e |

| CC-CP10% | 77.68 ± 0.12 b | 265.34 ± 0.24 a | 79.09 ± 0.95 a | 18.60 ± 0.07 e |

| GG-CP5% | 68.05 ± 0.14 e | 105.59 ± 0.76 e | 55.86 ± 0.19 d | 15.19 ± 0.17 f |

| GG-CP7.5% | 73.64 ± 0.34 c | 160.00 ± 1.61 d | 67.91 ± 1.84 c | 19.51 ± 0.07 cd |

| GG-CP10% | 80.00 ± 0.68 a | 205.07 ± 5.98 b | 81.26 ± 0.41 a | 20.34 ± 0.05 a |

| XG-CP5% | 34.23 ± 0.13 j | 160.07 ± 9.21 d | 70.80 ± 3.32 c | 18.84 ± 0.17 e |

| XG-CP7.5% | 62.02 ± 3.52 g | 175.40 ± 0.00 cd | 74.31 ± 0.82 b | 19.78 ± 0.02 bc |

| XG-CP10% | 58.79 ± 0.06 h | 181.70 ± 2.94 c | 82.17 ± 0.40 a | 19.99 ± 0.00 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Prakitchaiwattana, C.; Zheng, J.-S.; Siriamornpun, S. Incorporating Cricket Powder into Salad Dressing: Enhancing Protein Content and Functional Attributes Through Partial Palm-Oil Replacement. Foods 2025, 14, 4268. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244268

Guo Y, Liu Y, Li H, Prakitchaiwattana C, Zheng J-S, Siriamornpun S. Incorporating Cricket Powder into Salad Dressing: Enhancing Protein Content and Functional Attributes Through Partial Palm-Oil Replacement. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4268. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244268

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Yanjun, Yu Liu, Hua Li, Chuenjit Prakitchaiwattana, Ju-Sheng Zheng, and Sirithon Siriamornpun. 2025. "Incorporating Cricket Powder into Salad Dressing: Enhancing Protein Content and Functional Attributes Through Partial Palm-Oil Replacement" Foods 14, no. 24: 4268. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244268

APA StyleGuo, Y., Liu, Y., Li, H., Prakitchaiwattana, C., Zheng, J.-S., & Siriamornpun, S. (2025). Incorporating Cricket Powder into Salad Dressing: Enhancing Protein Content and Functional Attributes Through Partial Palm-Oil Replacement. Foods, 14(24), 4268. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244268