Short-Term Dietary Exposure to Ochratoxin A, Zearalenone or Fumonisins in Broiler Chickens: Effects on Cytochrome P450 Enzymes, Drug Transporters and Antioxidant Defence Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Contaminated Diets and MYC Analysis

2.2. LC-FLD/PDA/MS Analysis of MYC

2.3. Experimental Design and Sample Collection

2.4. Growth Performance and Productive Parameters

2.5. Assessment of Serum Antioxidant Capacity (SAC)

2.6. Assessment of Lipid Peroxidation

2.7. Total GSH Content and Enzymatic Activities

2.8. Gene Expression Analysis: RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and qRT-PCR

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect on MYC on Growth Performance and Productive Parameters

3.2. Effect of MYC on Systemic and Hepatic OS Parameters

3.3. Effect of MYC on Liver GSH—Dependent Enzymes and NQO1 Activity

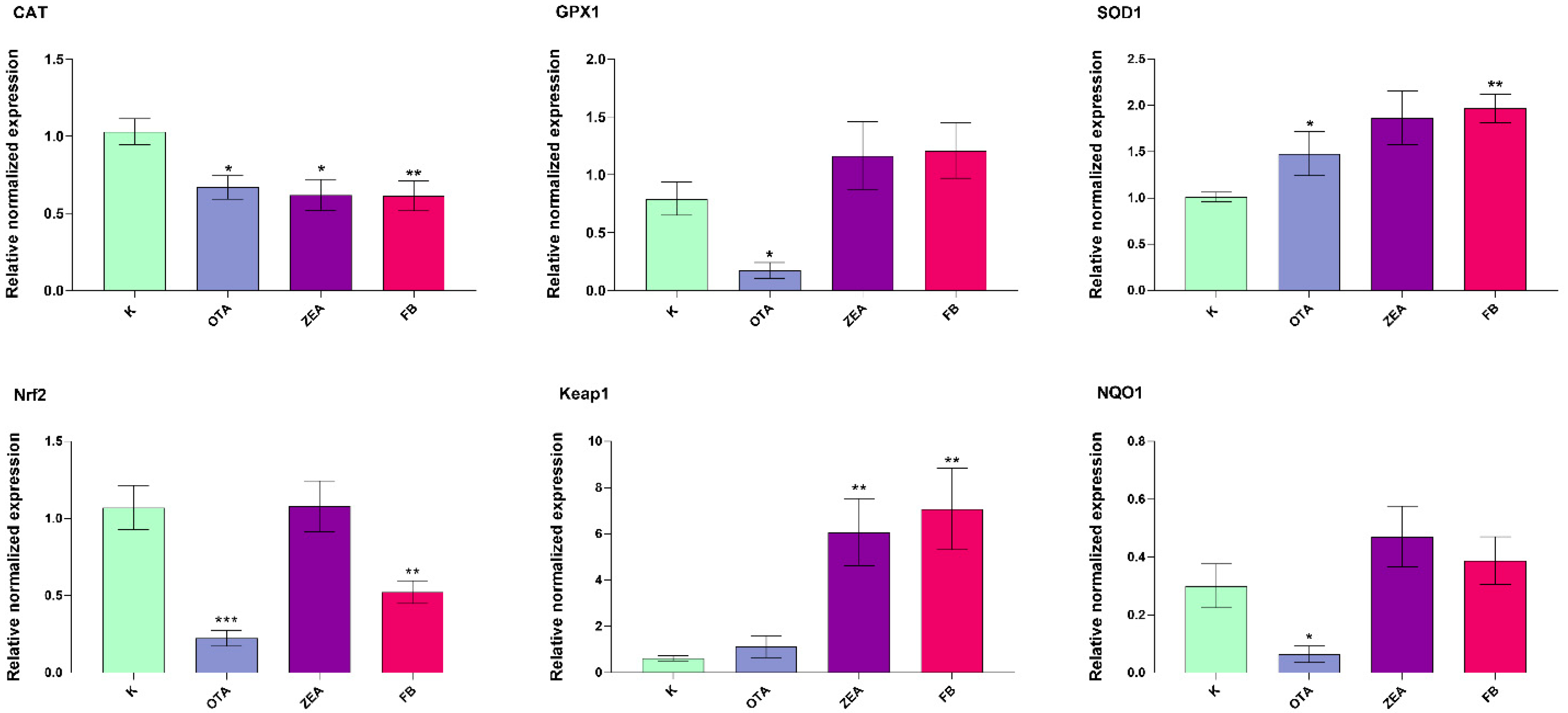

3.4. Effect of MYC on OS-Related Gene Expression in Liver and Duodenum

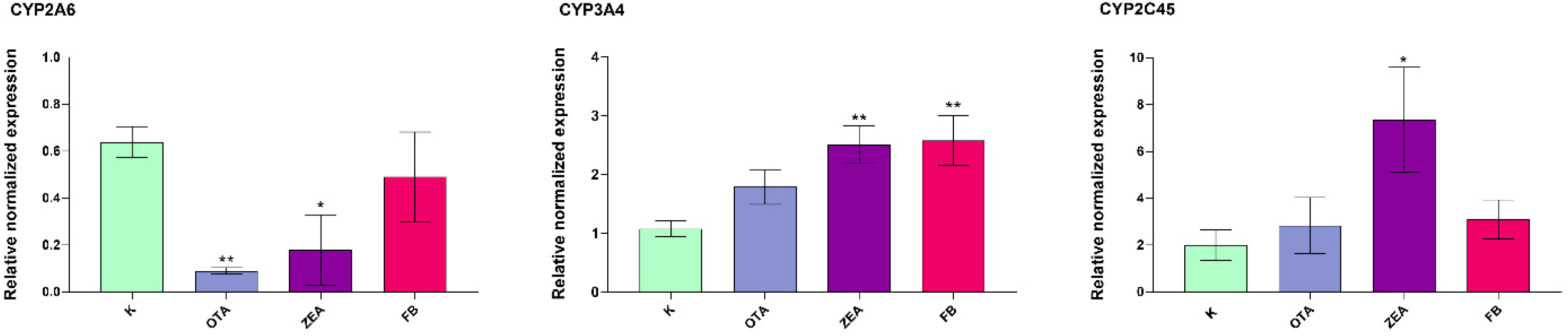

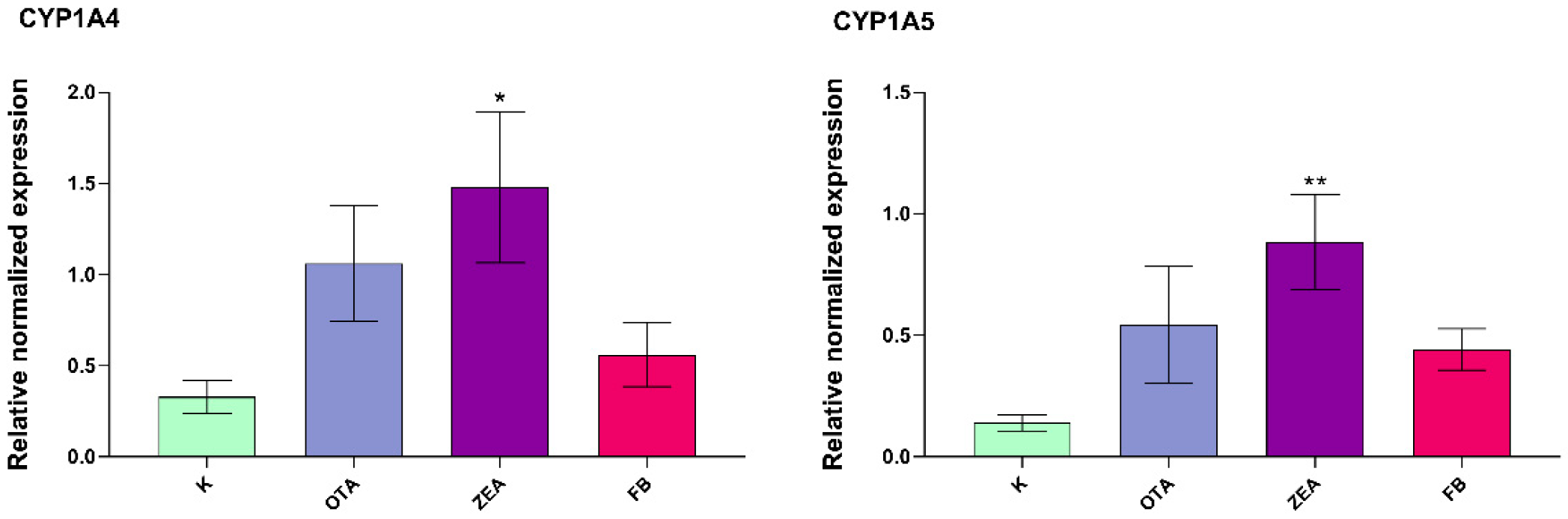

3.5. Effect of MYC on the Expression of Cytochrome P450s (CYPs) and 3β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase

3.6. Effect of MYC on the Expression of Hepatic and Intestinal Drug Transporters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hafez, H.M.; Attia, Y.A. Challenges to the Poultry Industry: Current Perspectives and Strategic Future After the COVID-19 Outbreak. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerre, P. Worldwide Mycotoxins Exposure in Pig and Poultry Feed Formulations. Toxins 2016, 8, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelrahman, R.E.; Khalaf, A.A.A.; Elhady, M.A.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Hassanen, E.I.; Noshy, P.A. Antioxidant and Antiapoptotic Effects of Quercetin against Ochratoxin A-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Broiler Chickens. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 96, 103982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tardieu, D.; Travel, A.; Le Bourhis, C.; Metayer, J.-P.; Mika, A.; Cleva, D.; Boissieu, C.; Guerre, P. Fumonisins and Zearalenone Fed at Low Levels Can Persist Several Days in the Liver of Turkeys and Broiler Chickens after Exposure to the Contaminated Diet Was Stopped. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 148, 111968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hua, X.; Shi, J.; Jing, N.; Ji, T.; Lv, B.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y. Ochratoxin A: Occurrence and Recent Advances in Detoxification. Toxicon 2022, 210, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, M.S.; Jeyaram, K.; Datta, S.; Chandrasekar, N.; Balaji, R.; Selvarajan, E. Detection, Contamination, Toxicity, and Prevention Methods of Ochratoxins: An Update Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 13974–13989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galtier, P.; Alvinerie, M. The Pharmacokinetic Profiles of Ochratoxin a in Pigs, Rabbits and Chickens. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 1981, 19, 735–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.A.; Khan, M.Z.; Hassan, Z.U.; Saleemi, M.K.; Saqib, M.; Khatoon, A.; Akhter, M. Comparative Efficacy of Bentonite Clay, Activated Charcoal and Trichosporon Mycotoxinivorans in Regulating the Feed-to-Tissue Transfer of Mycotoxins. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, I.; Ramos, A.J.; Raj, J.; Jakovčević, Z.; Farkaš, H.; Vasiljević, M.; Pérez-Vendrell, A.M. Effect of a Mycotoxin Binder (MMDA) on the Growth Performance, Blood and Carcass Characteristics of Broilers Fed Ochratoxin A and T-2 Mycotoxin Contaminated Diets. Animals 2021, 11, 3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM); Knutsen, H.; Alexander, J.; Barregård, L.; Bignami, M.; Brüschweiler, B.; Ceccatelli, S.; Cottrill, B.; Dinovi, M.; Edler, L.; et al. Risks for Animal Health Related to the Presence of Zearalenone and Its Modified Forms in Feed. EFS2 2017, 15, e04851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Ren, C.; Gong, Y.; Gao, X.; Rajput, S.A.; Qi, D.; Wang, S. The Insensitive Mechanism of Poultry to Zearalenone: A Review. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wen, C.; Wang, W.; Kang, Y.; Wang, A.; Zhou, Y. The Protective Effects of Modified Palygorskite on the Broilers Fed a Purified Zearalenone-Contaminated Diet. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 3802–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Norred, W.P.; Bacon, C.W.; Riley, R.T.; Merrill, A.H. Inhibition of Sphingolipid Biosynthesis by Fumonisins. Implications for Diseases Associated with Fusarium Moniliforme. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 14486–14490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerre, P. Fusariotoxins in Avian Species: Toxicokinetics, Metabolism and Persistence in Tissues. Toxins 2015, 7, 2289–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonissen, G.; De Baere, S.; Novak, B.; Schatzmayr, D.; Den Hollander, D.; Devreese, M.; Croubels, S. Toxicokinetics of Hydrolyzed Fumonisin B1 after Single Oral or Intravenous Bolus to Broiler Chickens Fed a Control or a Fumonisins-Contaminated Diet. Toxins 2020, 12, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonissen, G.; Croubels, S.; Pasmans, F.; Ducatelle, R.; Eeckhaut, V.; Devreese, M.; Verlinden, M.; Haesebrouck, F.; Eeckhout, M.; De Saeger, S.; et al. Fumonisins Affect the Intestinal Microbial Homeostasis in Broiler Chickens, Predisposing to Necrotic Enteritis. Vet. Res. 2015, 46, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauber, R.H.; Oliveira, M.S.; Mallmann, A.O.; Dilkin, P.; Mallmann, C.A.; Giacomini, L.Z.; Nascimento, V.P. Effects of Fumonisin B1 on Selected Biological Responses and Performance of Broiler Chickens. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2013, 33, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E.O.; Bracarense, A.P.F.L.; Oswald, I.P. Mycotoxins and Oxidative Stress: Where Are We? World Mycotoxin J. 2018, 11, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galtier, P. Biotransformation and Fate of Mycotoxins. J. Toxicol. Toxin Rev. 1999, 18, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanger, U.M.; Schwab, M. Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Drug Metabolism: Regulation of Gene Expression, Enzyme Activities, and Impact of Genetic Variation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Dohnal, V.; Huang, L.; Kuca, K.; Wang, X.; Chen, G.; Yuan, Z. Metabolic Pathways of Ochratoxin A. Curr. Drug Metab. 2011, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, H.; De Saeger, S.; De Boevre, M.; Sun, F.; Zhang, S.; Cao, X.; Wang, Z. In Vitro and in Vivo Metabolism of Ochratoxin A: A Comparative Study Using Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Quadrupole/Time-of-Flight Hybrid Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 3579–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleck, S.C.; Hildebrand, A.A.; Müller, E.; Pfeiffer, E.; Metzler, M. Genotoxicity and Inactivation of Catechol Metabolites of the Mycotoxin Zearalenone. Mycotoxin Res. 2012, 28, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marvasi, L.; Marin, D.; Viadère, J.L.; Laffitte, J.; Oswald, I.P.; Galtier, P.; Loiseau, N. Interaction between Fumonisin B1 and Pig Liver Cytochromes P450. In Mycotoxins and Phycotoxins; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Antonissen, G.; Devreese, M.; De Baere, S.; Martel, A.; Van Immerseel, F.; Croubels, S. Impact of Fusarium mycotoxins on Hepatic and Intestinal mRNA Expression of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes and Drug Transporters, and on the Pharmacokinetics of Oral Enrofloxacin in Broiler Chickens. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 101, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Jiang, J.; Deng, Y. Chicken Cytochrome P450 1A5 Is the Key Enzyme for Metabolizing T-2 Toxin to 3’OH-T-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 10809–10818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osselaere, A.; Li, S.J.; De Bock, L.; Devreese, M.; Goossens, J.; Vandenbroucke, V.; Van Bocxlaer, J.; Boussery, K.; Pasmans, F.; Martel, A.; et al. Toxic Effects of Dietary Exposure to T-2 Toxin on Intestinal and Hepatic Biotransformation Enzymes and Drug Transporter Systems in Broiler Chickens. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 55, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virkel, G.; Ballent, M.; Lanusse, C.; Lifschitz, A. Role of ABC Transporters in Veterinary Medicine: Pharmaco-Toxicological Implications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 1251–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritova, A.M.; Schrickx, J.; Fink-Gremmels, J. Expression of Drug Efflux Transporters in Poultry Tissues. Res. Vet. Sci. 2010, 89, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, L.; Halwachs, S.; Girolami, F.; Badino, P.; Honscha, W.; Nebbia, C. Interaction of Mammary Bovine ABCG2 with AFB1 and Its Metabolites and Regulation by PCB 126 in a MDCKII in Vitro Model. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 40, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amminikutty, N.; Spalenza, V.; Jarriyawattanachaikul, W.; Badino, P.; Capucchio, M.T.; Colombino, E.; Schiavone, A.; Greco, D.; D’Ascanio, V.; Avantaggiato, G.; et al. Turmeric Powder Counteracts Oxidative Stress and Reduces AFB1 Content in the Liver of Broilers Exposed to the EU Maximum Levels of the Mycotoxin. Toxins 2023, 15, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrenk, D.; Cartus, A. Chemical Contaminants and Residues in Food, 2nd ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, M.A.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Li, X.; Saleemi, M.K.; He, C. Mycotoxin Contamination and Control Strategy in Human, Domestic Animal and Poultry: A Review. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 142, 104095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, H.; Liu, X.; Jin, J.; Xing, F. Current Status of Major Mycotoxins Contamination in Food and Feed in Africa. Food Control 2020, 110, 106975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 17372:2008; Animal Feeding Stuffs—Determination of Zearalenone by Immunoaffinity Column Chromatography and High Performance Liquid Chromatography. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- EN 16007:2009; Animal Feeding Stuffs—Determination of Ochratoxin A in Animal Feed by Immunoaffinity Column Clean-Up and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Fluorescence Detection. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Bruxelles, Belgium, 2011.

- Solfrizzo, M.; Gambacorta, L.; Bibi, R.; Ciriaci, M.; Paoloni, A.; Pecorelli, I. Multimycotoxin Analysis by LC-MS/MS in Cereal Food and Feed: Comparison of Different Approaches for Extraction, Purification, and Calibration. J. AOAC Int. 2018, 101, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragoubi, C.; Quintieri, L.; Greco, D.; Mehrez, A.; Maatouk, I.; D’Ascanio, V.; Landoulsi, A.; Avantaggiato, G. Mycotoxin Removal by Lactobacillus spp. and Their Application in Animal Liquid Feed. Toxins 2021, 13, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damiano, S.; Jarriyawattanachaikul, W.; Girolami, F.; Longobardi, C.; Nebbia, C.; Andretta, E.; Lauritano, C.; Dabbou, S.; Avantaggiato, G.; Schiavone, A.; et al. Curcumin Supplementation Protects Broiler Chickens Against the Renal Oxidative Stress Induced by the Dietary Exposure to Low Levels of Aflatoxin B1. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 8, 822227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espín, S.; Sánchez-Virosta, P.; García-Fernández, A.J.; Eeva, T. A microplate adaptation of the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay to determine lipid peroxidation fluorometrically in small sample volumes. Rev. Toxicol. 2017, 34, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Nebbia, C.; Dacasto, M.; Rossetto Giaccherino, A.; Giuliano Albo, A.; Carletti, M. Comparative Expression of Liver Cytochrome P450-Dependent Monooxygenases in the Horse and in Other Agricultural and Laboratory Species. Vet. J. 2003, 165, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.C.; Francetic, D.J. The Importance of Sample Preparation and Storage in Glutathione Analysis. Anal. Biochem. 1993, 211, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuccato, M.; Amminikutty, N.; Spalenza, V.; Conte, V.; Bagatella, S.; Greco, D.; D’Ascanio, V.; Gai, F.; Schiavone, A.; Avantaggiato, G.; et al. Innovative Mycotoxin Detoxifying Agents Decrease the Absorption Rate of Aflatoxin B1 and Counteract the Oxidative Stress in Broiler Chickens Exposed to Low Dietary Levels of the Mycotoxin. Toxins 2025, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weydert, C.J.; Cullen, J.J. Measurement of Superoxide Dismutase, Catalase and Glutathione Peroxidase in Cultured Cells and Tissue. Nat. Protoc. 2010, 5, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, C.; Cadenas, E.; Hochstein, P.; Ernster, L. DT-Diaphorase: Purification, Properties, and Function. Methods Enzymol. 1990, 186, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekinejad, H.; Maas-Bakker, R.; Fink-Gremmels, J. Species Differences in the Hepatic Biotransformation of Zearalenone. Vet. J. 2006, 172, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudergue, C.; Burel, C.; Dragacci, S.; Favrot, M.-C.; Fremy, J.-M.; Massimi, C.; Prigent, P.; Debongnie, P.; Pussemier, L.; Boudra, H.; et al. Review of Mycotoxin-Detoxifying Agents Used as Feed Additives: Mode of Action, Efficacy and Feed/Food Safety. EFSA Support. Publ. 2009, 6, 22E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.C.S.; Galli, G.M.; Alba, D.F.; Griss, L.G.; Gebert, R.R.; Souza, C.F.; Baldissera, M.D.; Gloria, E.M.; Mendes, R.E.; Zanelato, G.O.; et al. Pathogenetic Effects of Feed Intake Containing of Fumonisin (Fusarium verticillioides) in Early Broiler Chicks and Consequences on Weight Gain. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 147, 104247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Qin, C.; Jin, B.; Liang, Z.; Yang, S.; Li, L.; Long, M. Protective Effects of Astaxanthin on Ochratoxin A-Induced Liver Injury: Effects of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Mitochondrial Fission–Fusion Balance. Toxins 2024, 16, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olariu, R.M.; Fiţ, N.I.; Bouari, C.M.; Nadăş, G.C. Mycotoxins in Broiler Production: Impacts on Growth, Immunity, Vaccine Efficacy, and Food Safety. Toxins 2025, 17, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kövesi, B.; Cserháti, M.; Erdélyi, M.; Zándoki, E.; Mézes, M.; Balogh, K. Long-Term Effects of Ochratoxin A on the Glutathione Redox System and Its Regulation in Chicken. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Li, K.; Zou, C.; Tong, C.; Sun, L.; Cao, Z.; Yang, S.; Lyu, Q. Selenium Yeast Alleviates Ochratoxin A-Induced Hepatotoxicity via Modulation of the PI3K/AKT and Nrf2/Keap1 Signaling Pathways in Chickens. Toxins 2020, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Ren, C.; Yang, P.; Qi, D. Effects of Intestinal Microorganisms on Metabolism and Toxicity Mitigation of Zearalenone in Broilers. Animals 2022, 12, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tan, R.; Liu, G.; He, W.; Luo, S.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Y. No Toxic Effects or Interactions between Aflatoxin B1 and Zearalenone in Broiler Chickens Fed Diets at China’s Regulatory Limits. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 159, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poersch, A.B.; Trombetta, F.; Braga, A.C.M.; Boeira, S.P.; Oliveira, M.S.; Dilkin, P.; Mallmann, C.A.; Fighera, M.R.; Royes, L.F.F.; Oliveira, M.S.; et al. Involvement of Oxidative Stress in Subacute Toxicity Induced by Fumonisin B1 in Broiler Chicks. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 174, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, G.M.; Griss, L.G.; Fortuoso, B.F.; Silva, A.D.; Fracasso, M.; Lopes, T.F.; Schetinger, M.R.S.; Gundel, S.; Ourique, A.F.; Carneiro, C.; et al. Feed Contaminated by Fumonisin (Fusarium spp.) in Chicks Has a Negative Influence on Oxidative Stress and Performance, and the Inclusion of Curcumin-Loaded Nanocapsules Minimizes These Effects. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 148, 104496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.-J.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, X.; Yu, X.; Castellino, F.J. Analysis and Characterization of Glutathione Peroxidases in an Environmental Microbiome and Isolated Bacterial Microorganisms. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 33, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellou, J.; Ross, N.W.; Moon, T.W. Glutathione, Glutathione S-Transferase, and Glutathione Conjugates, Complementary Markers of Oxidative Stress in Aquatic Biota. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 2007–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortuoso, B.F.; Galli, G.M.; Griss, L.G.; Armanini, E.H.; Silva, A.D.; Fracasso, M.; Mostardeiro, V.; Morsch, V.M.; Lopes, L.Q.S.; Santos, R.C.V.; et al. Effects of Glycerol Monolaurate on Growth and Physiology of Chicks Consuming Diet Containing Fumonisin. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 147, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Li, S.; Jiang, L.; Gao, X.; Liu, W.; Zhu, X.; Huang, W.; Zhao, H.; Wei, Z.; Wang, K.; et al. Baicalin Protects against Zearalenone-Induced Chicks Liver and Kidney Injury by Inhibiting Expression of Oxidative Stress, Inflammatory Cytokines and Caspase Signaling Pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 100, 108097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atia, A.; Alrawaiq, N.; Abdullah, A. A Review of NAD(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1); A Multifunctional Antioxidant Enzyme. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 4, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes-Agudo, M.; Luque-Tévar, M.; Cucarella, C.; Martín-Sanz, P.; Casado, M. Advances in Understanding the Role of NRF2 in Liver Pathophysiology and Its Relationship with Hepatic-Specific Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kövesi, B.; Worlanyo, A.P.; Kulcsár, S.; Ancsin, Z.; Erdélyi, M.; Zándoki, E.; Mézes, M.; Balogh, K. Curcumin Mitigates Ochratoxin A-Induced Oxidative Stress and Alters Gene Expression in Broiler Chicken Liver and Kidney. Acta Vet. Hung. 2024, 72, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Xie, S.; Xu, F.; Liu, A.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Pan, Y.; Huang, L.; Peng, D.; Wang, X.; et al. Ochratoxin A: Toxicity, Oxidative Stress and Metabolism. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 112, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappari, L.; Dasireddy, J.R.; Applegate, T.J.; Selvaraj, R.K.; Shanmugasundaram, R. MicroRNAs: Exploring their role in farm animal disease and mycotoxin challenges. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1372961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, E.J.; Park, K.T. Roles of microRNAs in multiple organs under mycotoxin stress by bioinformatic analysis: microRNA regulation during mycotoxin exposure. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q. Role of Nrf2 in Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraskeuas, V.; Griela, E.; Bouziotis, D.; Fegeros, K.; Antonissen, G.; Mountzouris, K.C. Effects of Deoxynivalenol and Fumonisins on Broiler Gut Cytoprotective Capacity. Toxins 2021, 13, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, C. Cytochrome P450 Expression in the Liver of Food-Producing Animals. Curr. Drug Metab. 2006, 7, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, T.; Obe, Y.; Ogura, C.; Goto, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Nakamura, M.; Kanamaru, K.; Yamagata, H.; Imaishi, H. Metabolism of 7-ethoxycoumarin, Safrole, Flavanone and Hydroxyflavanone by Cytochrome P450 2A6 Variants. Biopharm. Drug Disp. 2013, 34, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.P.; Kawai, Y.K.; Ikenaka, Y.; Kawata, M.; Ikushiro, S.-I.; Sakaki, T.; Ishizuka, M. Avian Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1-3 Family Genes: Isoforms, Evolutionary Relationships, and mRNA Expression in Chicken Liver. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, G.J.; Murcia, H.W.; Cepeda, S.M. Cytochrome P450 Enzymes Involved in the Metabolism of Aflatoxin B1 in Chickens and Quail. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 2461–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, N.-Y.; Karrow, N.A.; Krumm, C.S.; Qi, D.-S.; Sun, L.-H. Aflatoxin B1 Metabolism: Regulation by Phase I and II Metabolizing Enzymes and Chemoprotective Agents. Mutat. Res./Rev. Mutat. Res. 2018, 778, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, G.J.; Murcia, H.W.; Cepeda, S.M. Bioactivation of Aflatoxin B1 by Turkey Liver Microsomes: Responsible Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. Br. Poult. Sci. 2010, 51, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.P.; Abou-Donia, M.B. Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Chickens: Characteristics and Induction by Xenobiotics. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Pharmacol. Toxicol. Endocrinol. 1998, 121, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravin, F.; Duca, R.C.; Balaguer, P.; Delaforge, M. In Vitro Cytochrome P450 Formation of a Mono-Hydroxylated Metabolite of Zearalenone Exhibiting Estrogenic Activities: Possible Occurrence of This Metabolite In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 1824–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, E.; Kommer, A.; Dempe, J.S.; Hildebrand, A.A.; Metzler, M. Absorption and Metabolism of the Mycotoxin Zearalenone and the Growth Promotor Zeranol in Caco-2 Cells in Vitro. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, F.; De Ruyck, K.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; De Saeger, S.; et al. Metabolic Profile of Zearalenone in Liver Microsomes from Different Species and Its in Vivo Metabolism in Rats and Chickens Using Ultra High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography-Quadrupole/Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 11292–11303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duca, R.; Mabondzo, A.; Bravin, F.; Delaforge, M. In Vivo Effects of Zearalenone on the Expression of Proteins Involved in the Detoxification of Rat Xenobiotics. Environ. Toxicol. 2012, 27, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, Y.; Guo, C.; Wang, J.; Boral, D.; Nie, D. Nuclear Receptors in the Multidrug Resistance through the Regulation of Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes and Drug Transporters. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 83, 1112–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W. Xenobiotic Receptors, a Journey of Rewards. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2023, 51, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handschin, C.; Podvinec, M.; Meyer, U.A. CXR, a Chicken Xenobiotic-Sensing Orphan Nuclear Receptor, Is Related to Both Mammalian Pregnane X Receptor (PXR) and Constitutive Androstane Receptor (CAR). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 10769–10774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayed-Boussema, I.; Pascussi, J.M.; Maurel, P.; Bacha, H.; Hassen, W. Zearalenone Activates Pregnane X Receptor, Constitutive Androstane Receptor and Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and Corresponding Phase I Target Genes mRNA in Primary Cultures of Human Hepatocytes. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2011, 31, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Lichti, K.; Staudinger, J.L. The Mycoestrogen Zearalenone Induces CYP3A through Activation of the Pregnane X Receptor. Toxicol. Sci. 2006, 91, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ourlin, J.-C.; Baader, M.; Fraser, D.; Halpert, J.R.; Meyer, U.A. Cloning and Functional Expression of a First Inducible Avian Cytochrome P450 of the CYP3A Subfamily (CYP3A37). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 373, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynal, M.; Bailly, J.D.; Benard, G.; Guerre, P. Effects of Fumonisin B1 Present in Fusarium moniliforme Culture Material on Drug Metabolising Enzyme Activities in Ducks. Toxicol. Lett. 2001, 121, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulcsár, A.; Mátis, G.; Molnár, A.; Petrilla, J.; Wágner, L.; Fébel, H.; Husvéth, F.; Dublecz, K.; Neogrády, Z. Nutritional Modulation of Intestinal Drug-Metabolizing Cytochrome P450 by Butyrate of Different Origin in Chicken. Res. Vet. Sci. 2017, 113, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, M.; Pettersson, H.; Sandholm, K.; Visconti, A.; Kiessling, K.-H. Metabolism of Zearalenone by Sow Intestinal Mucosa in Vitro. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1987, 25, 681–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, G.J.; Murcia, H.W.; Cepeda, S.M.; Boermans, H.J. The Role of Selected Cytochrome P450 Enzymes on the Bioactivation of Aflatoxin B1 by Duck Liver Microsomes. Avian Pathol. 2010, 39, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrickx, J.A.; Fink-Gremmels, J. Implications of ABC Transporters on the Disposition of Typical Veterinary Medicinal Products. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 585, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.M. Expression of P-Glycoprotein in the Chicken. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001, 130, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Deng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Gene Expression of Abcc2 and Its Regulation by Chicken Xenobiotic Receptor. Toxics 2024, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, M.; Lu, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Chicken Xenobiotic Receptor Upregulates the BCRP/ABCG2 Transporter. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, D.; D’Ascanio, V.; Abbasciano, M.; Santovito, E.; Garbetta, A.; Logrieco, A.F.; Avantaggiato, G. Simultaneous Removal of Mycotoxins by a New Feed Additive Containing a Tri-Octahedral Smectite Mixed with Lignocellulose. Toxins 2022, 14, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| K | OTA | ZEA | FB | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial body weight (d23) (g) | 1011 ± 10 | 1004 ± 12 | 996 ± 11 | 993 ±11 | 0.509 |

| Final body weight (d32) (g) | 1944 ± 18 | 1968 ± 14 | 1959 ± 22 | 1965 ± 10 | 0.407 |

| ADFI 23–32 days of age (g) | 143 ± 2.6 | 145 ± 4.8 | 149 ± 3.9 | 144 ± 1.3 | 0.647 |

| FCR 23–32 days of age | 1.53 ± 0.01 | 1.51 ± 0.2 | 1.53 ± 0.03 | 1.49 ± 0.1 | 0.951 |

| MYC intake (µg MYC/kg BW/day) | - | 0.025 ± 0.002 | 0.293 ± 0.017 | 5.967 ± 0.128 | - |

| Parameter | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | OTA | ZEA | FB | |

| Total GST (nmol/min/mg protein) | 523.8 ± 27.66 | 382.5 ± 18.03 *** | 365.9 ± 16.77 *** | 297.1 ± 20.23 *** |

| µ-class GST (nmol/min/mg protein) | 0.880 ± 0.10 | 0.643 ± 0.09 | 0.614 ± 0.09 | 0.732 ± 0.12 |

| GPx-selenium independent (α-class GST) | 17.00 ± 2.32 | 13.36 ± 3.49 | 9.61 ± 5.00 | 8.71 ± 3.03 |

| GPx-selenium dependent | 45.37 ±1.35 | 35.33 ± 2.02 ** | 35.35 ± 1.76 ** | 30.58 ± 2.10 *** |

| NQO1 (nmol/min/mg protein) | 367.5 ± 14.69 | 274.9 ± 17.27 *** | 234.6 ± 16.99 *** | 204.9 ± 7.40 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amminikutty, N.; Cuccato, M.; Jarriyawattanachaikul, W.; Gariglio, M.; Greco, D.; D’Ascanio, V.; Avantaggiato, G.; Schiavone, A.; Nebbia, C.; Girolami, F. Short-Term Dietary Exposure to Ochratoxin A, Zearalenone or Fumonisins in Broiler Chickens: Effects on Cytochrome P450 Enzymes, Drug Transporters and Antioxidant Defence Systems. Foods 2025, 14, 4249. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244249

Amminikutty N, Cuccato M, Jarriyawattanachaikul W, Gariglio M, Greco D, D’Ascanio V, Avantaggiato G, Schiavone A, Nebbia C, Girolami F. Short-Term Dietary Exposure to Ochratoxin A, Zearalenone or Fumonisins in Broiler Chickens: Effects on Cytochrome P450 Enzymes, Drug Transporters and Antioxidant Defence Systems. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4249. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244249

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmminikutty, Neenu, Matteo Cuccato, Watanya Jarriyawattanachaikul, Marta Gariglio, Donato Greco, Vito D’Ascanio, Giuseppina Avantaggiato, Achille Schiavone, Carlo Nebbia, and Flavia Girolami. 2025. "Short-Term Dietary Exposure to Ochratoxin A, Zearalenone or Fumonisins in Broiler Chickens: Effects on Cytochrome P450 Enzymes, Drug Transporters and Antioxidant Defence Systems" Foods 14, no. 24: 4249. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244249

APA StyleAmminikutty, N., Cuccato, M., Jarriyawattanachaikul, W., Gariglio, M., Greco, D., D’Ascanio, V., Avantaggiato, G., Schiavone, A., Nebbia, C., & Girolami, F. (2025). Short-Term Dietary Exposure to Ochratoxin A, Zearalenone or Fumonisins in Broiler Chickens: Effects on Cytochrome P450 Enzymes, Drug Transporters and Antioxidant Defence Systems. Foods, 14(24), 4249. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244249