Effects of Active Paper Sheets on the Quality of Cherry Tomatoes and Kale During Storage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Encapsulation of Essential Oils and Active Packaging Preparation

2.3. Packaging Treatments and Storage Conditions

2.4. Microbiological Analyses

2.5. Physicochemical and Firmness Analyses

2.6. Colour

2.7. Pigment Analyses

2.8. Total Vitamin C Content

2.9. Total Phenolic Content and Total Antioxidant Capacity

2.10. Mathematical Modelling of Microbial Response

2.11. Data Analysis for Quality Parameters

3. Results and Discussion

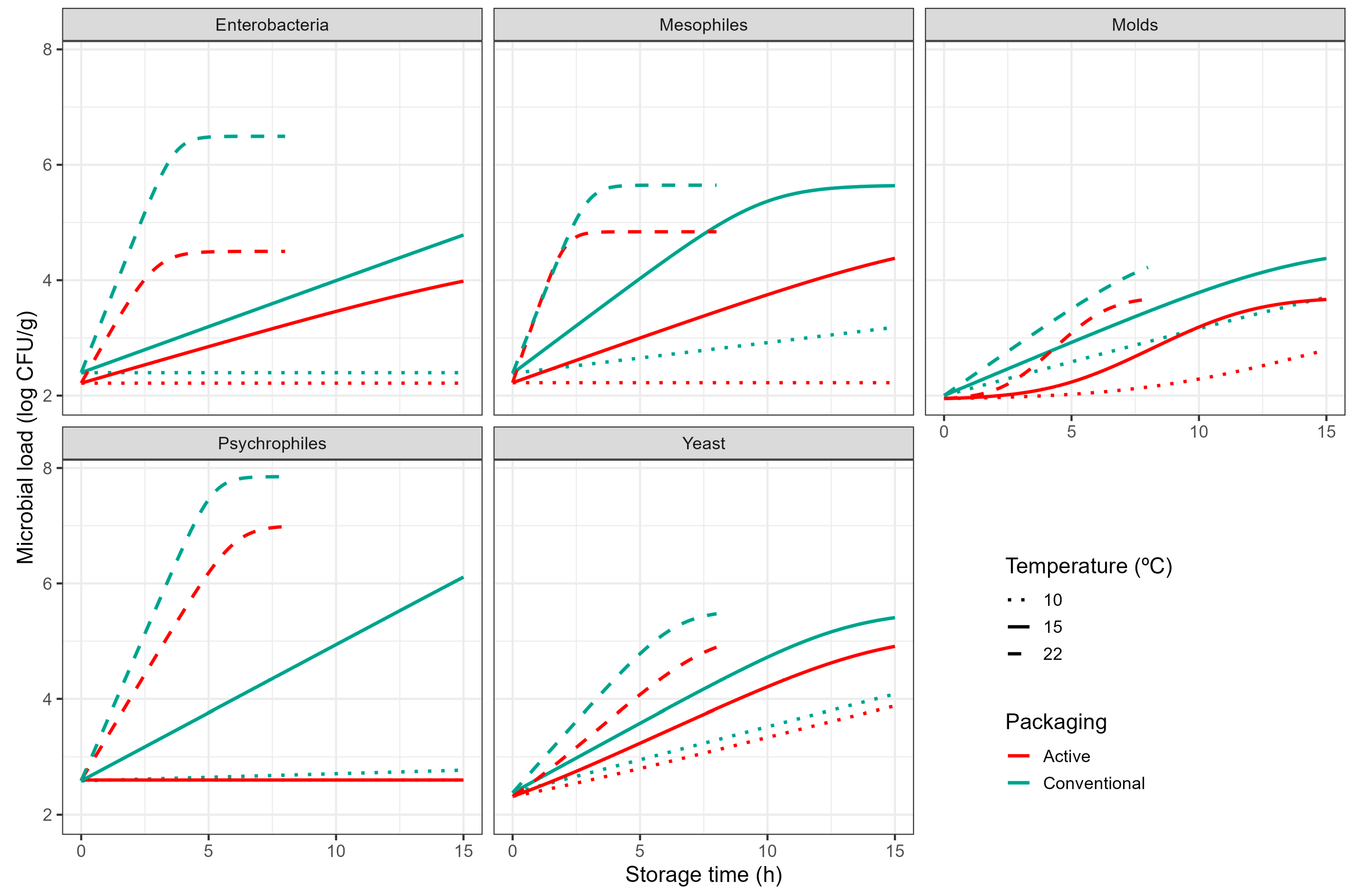

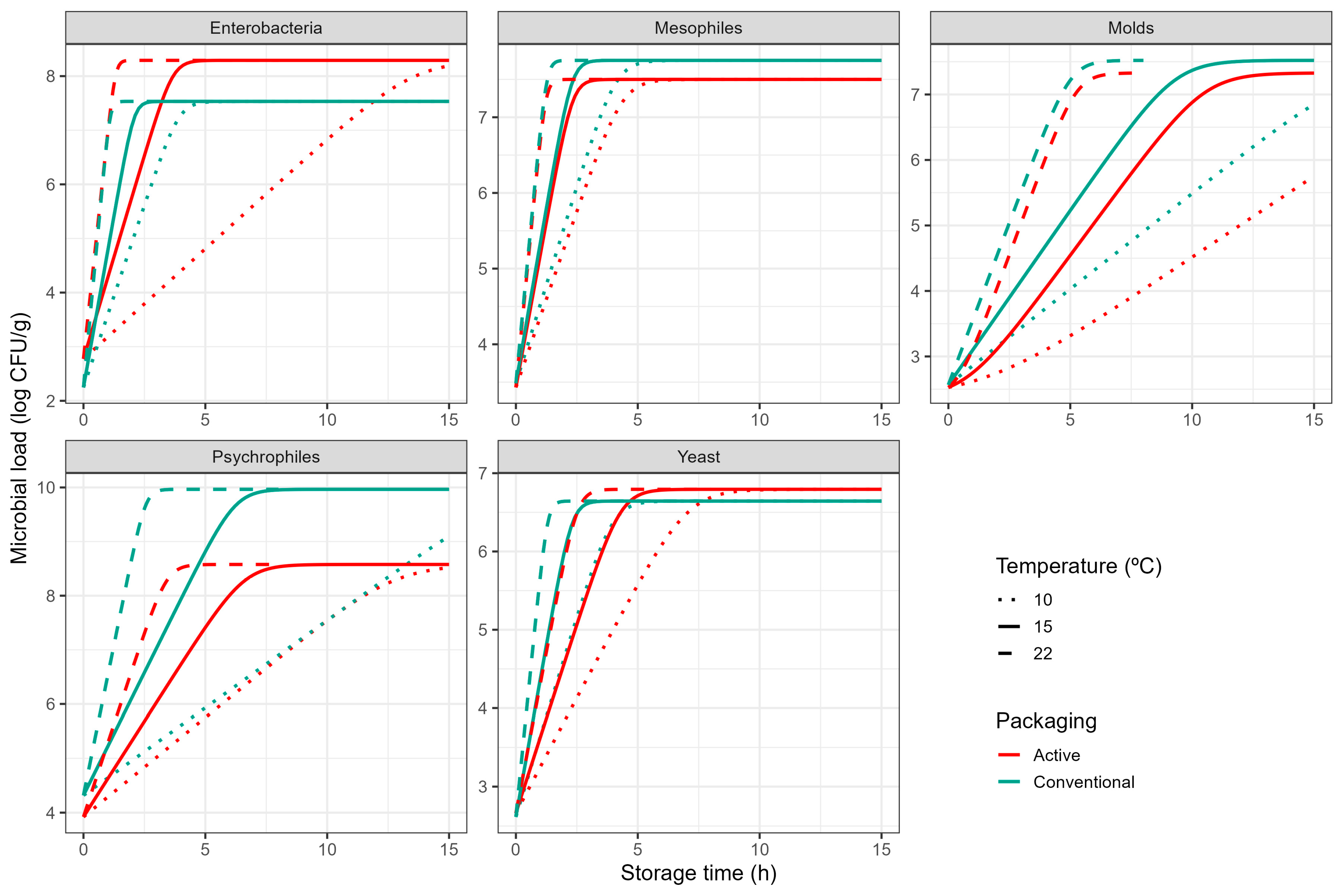

3.1. Microbiological Analysis

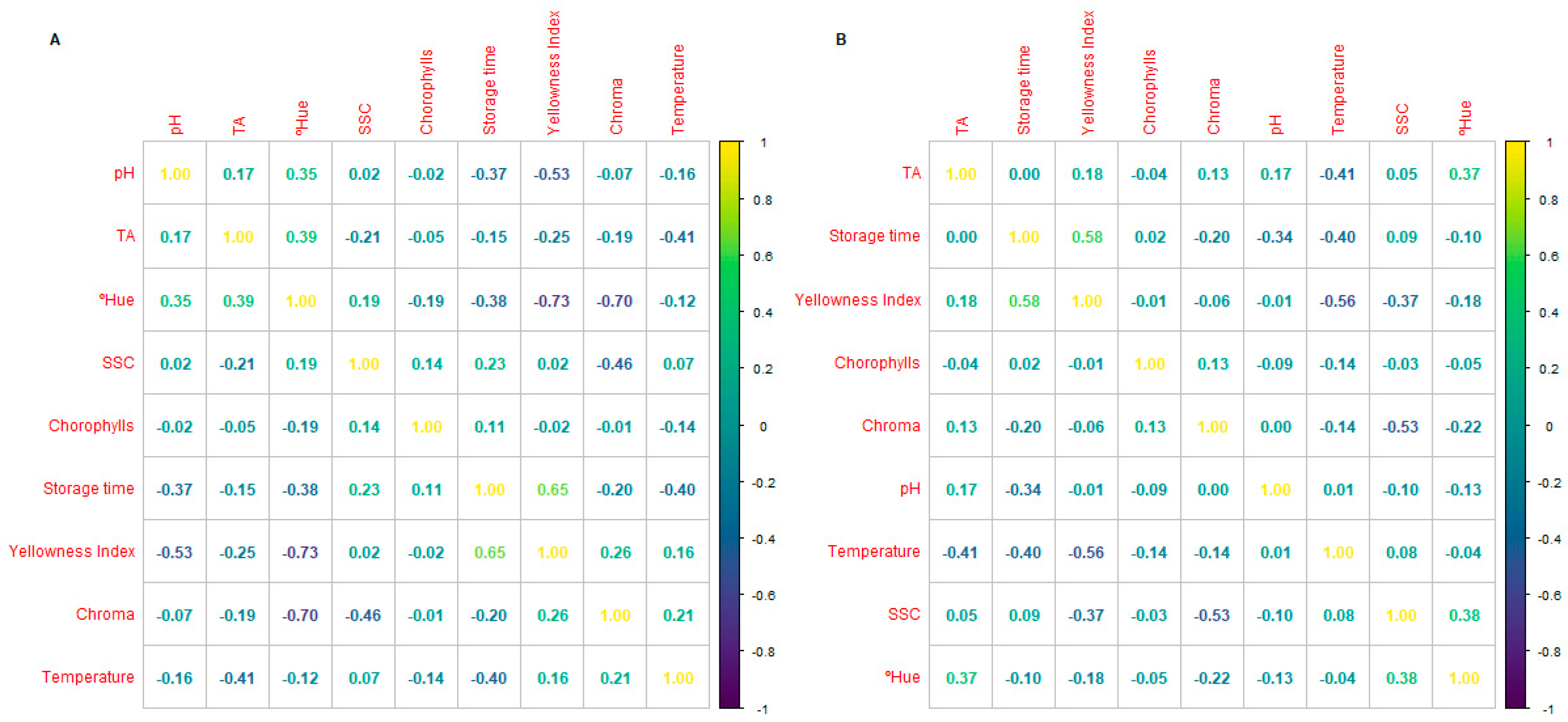

3.2. Physicochemical Quality

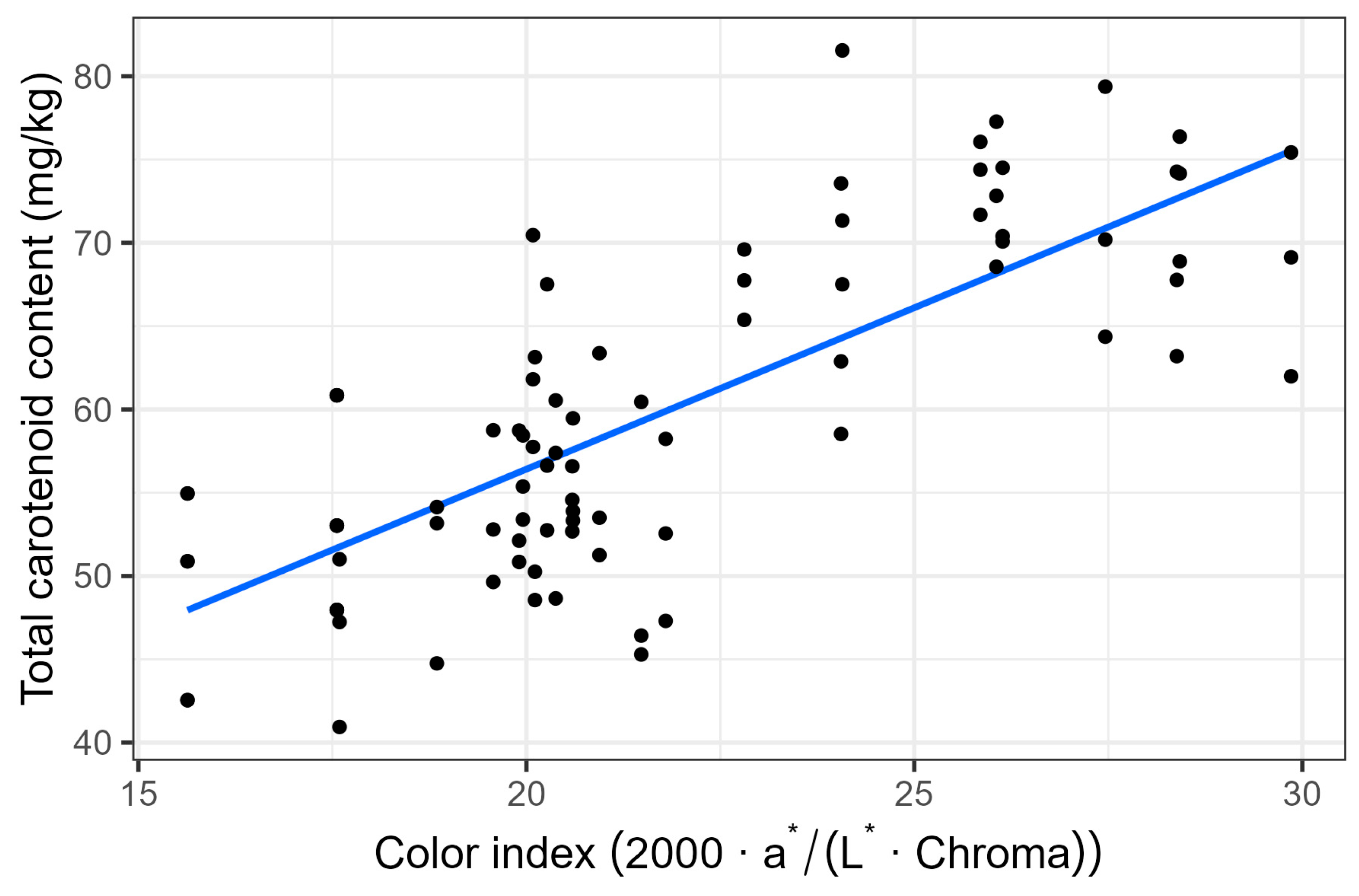

3.3. Colour and Pigments

3.4. Firmness

3.5. Bioactive Compounds and Total Antioxidant Capacity

3.5.1. Tomatoes: Bioactive Compounds and Total Antioxidant Capacity

3.5.2. Kale: Bioactive Compounds and Total Antioxidant Capacity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Ge, H. Volatile compound metabolism during cherry tomato fruit development and ripening. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 17, 2162–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, W.; Li, D.; Chan, A.S.C. Evaluation of nutritional compositions, bioactive components, and antioxidant activity of three cherry tomato varieties. Agronomy 2023, 13, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, H.; Su, Y.; Liu, H.; Hu, J.; Hong, K. Increased blood alpha-carotene, all-trans-Beta-carotene and lycopene levels are associated with beneficial changes in heart rate variability: A CVD-stratified analysis in an adult population-based study. Nutr. J. 2021, 20, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Cao, D.; Qiu, S.; Chen, B.; Li, J.; Bao, Y.; Wei, Q.; Han, P.; Liu, L. Vitamin C intake and cancers: An um-brella review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 812394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, L. Effect of postharvest storage temperature and duration on tomato fruit quality. Foods 2025, 14, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thole, V.; Vain, P.; Martin, C. Effect of elevated temperature on tomato post-harvest properties. Plants 2021, 10, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Rosado-Souza, L.; Sampathkumar, A.; Fernie, A.R. The relationship between cell wall and postharvest physiological deterioration of fresh produce. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 210, 108568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Zaid, M.I.; Tohamy, M.R.; Arisha, H.M.; Raafat, S.M. Role of modified atmosphere and some physical treatments under cool storage conditions in controlling post-harvest cherry tomatoes spoilage. Zagazig J. Agric. Res. 2020, 47, 1463–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárcena, A.; Martínez, G.; Costa, L. Low intensity light treatment improves purple kale (Brassica oleracea var. sabellica) post-harvest preservation at room temperature. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prade, T.; Muneer, F.; Berndtsson, E.; Nynäs, A.-L.; Svensson, S.-E.; Newson, W.R.; Johansson, E. Protein fractionation of broccoli (Brassica oleracea, var. Italica) and kale (Brassica oleracea, var. Sabellica) residual leaves—A pre-feasibility assessment and evaluation of fraction phenol and fibre content. Food Bioprod. Process. 2021, 130, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndtsson, E. Dietary fibre and phenolic compounds in broccoli (Brassica oleracea Italica group) and kale (Brassica oleracea Sabellica group). Swedish Univ. Agric. Sci. 2019, 1, 1–36. Available online: https://pub.epsilon.slu.se/16184/7/Berndtsson_E_190531.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Chung, M.J.; Lee, S.H.; Sung, N.J. Inhibitory effect of whole strawberries, garlic juice or kale juice on endogenous formation of N-nitrosodimethylamine in humans. Cancer Lett. 2002, 182, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenco, A.B.; Casajús, V.; Ramos, R.; Massolo, F.; Salinas, C.; Civello, P.; Martínez, G. Postharvest shelf life extension of minimally processed kale at ambient and refrigerated storage by use of modified atmosphere. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2024, 30, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angane, M.; Swift, S.; Huang, K.; Butts, C.A.; Quek, S.Y. Essential oils and their major components: An updated review on antimicrobial activities, mechanism of action and their potential application in the food industry. Foods 2022, 11, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gómez, A.; Navarro-Martínez, A.; Garre, A.; Artés-Hernández, F.; Villalba, P.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. The potential of essential oils from active packaging to reduce ethylene biosynthesis in plant products. Part 1: Vegetables (broccoli and tomato). Plants 2023, 12, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gómez, A.; Navarro-Martínez, A.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Effects of essential oils released from active packaging on the antioxidant system and quality of lemons during cold storage and commercialization. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 312, 111855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Levin, E.; Fallik, E.; Alkalai-Tuvia, S.; Foolad, M.R.; Lers, A. Physiological genetic variation in tomato fruit chilling tolerance during postharvest storage. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 991983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz, K.; Cantwell, M.I.; Zhang, L.; Beckles, D.M. Integrative analysis of postharvest chilling injury in cherry tomato fruit reveals contrapuntal spatio-temporal responses to ripening and cold stress. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buendía-Moreno, L.; Soto-Jover, S.; Ros-Chumillas, M.; Antolinos, V.; Navarro-Segura, L.; Sánchez-Martínez, M.J.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B.; López-Gómez, A. Innovative cardboard active packaging with a coating including encapsulated essential oils to extend cherry tomato shelf life. LWT 2019, 116, 108584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, F.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; García-Viguera, C. Potential bioactive compounds in health promotion from broccoli cultivars grown in Spain. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 1293–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, S.; Dufour, J.P. Ascorbic, dehydroascorbic and isoascorbic acid simultaneous determinations by reverse phase ion interaction HPLC. J. Food Sci. 1992, 57, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolinos, V.; Sánchez-Martínez, M.J.; Maestre-Valero, J.F.; López-Gómez, A.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Effects of irrigation with desalinated seawater and hydroponic system on tomato quality. Water 2020, 12, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, F.; Valero, A. Predictive Microbiology in Foods; Spinger: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranyi, J.; Roberts, T.A. A dynamic approach to predicting bacterial growth in food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1994, 23, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratkowsky, D.A.; Olley, J.; McMeekin, T.A.; Ball, A. Relationship between temperature and growth rate of bacterial cultures. J. Bacteriol. 1982, 149, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garre, A.; Valdramidis, V.; Guillén, S. Revisiting secondary model features for describing the shoulder and lag parameters of microbial inactivation and growth models. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 431, 111078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garre, A.; Tsagkaropoulou, T.; Guillén, S.; Karatzas, K.G.A.; Palop, A. Optimal strategies for estimating the parameters of the Baranyi-Ratkowsky model: From (optimal) experiment design to model fitting methods. Food Res. Int. 2025, 221, 117288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garre, A.; Koomen, J.; Besten, H.M.W.D.; Zwietering, M.H. Modeling population growth in r with the biogrowth Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2023, 107, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Georgalis, L.; Fernandez, P.S.; Garre, A. A protocol for predictive modeling of microbial inactivation based on experimental data. In Basic Protocols in Predictive Food Microbiology, 1st ed.; Ortiz-Alvarenga, V., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2023; Volume 5, pp. 79–119. [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe, M.D.; Rice, C.J.; Lucchini, S.; Pin, C.; Thompson, A.; Cameron, A.D.S.; Alston, M.; Stringer, M.F.; Betts, R.P.; Baranyi, J.; et al. Lag phase is a distinct growth phase that prepares bacteria for exponential growth and involves transient metal accumulation. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 686–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pott, D.M.; Vallarino, J.G.; Osorio, S. Metabolite changes during postharvest storage: Effects on fruit quality traits. Metabolites 2020, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Z. The role of different natural organic acids in postharvest fruit quality management and its mechanism. Food Front. 2023, 4, 1127–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.; Olmos, I.; Carballo, J.; Franco, I. Quality parameters of Brassica spp. grown in northwest Spain. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noichinda, S.; Bodhipadma, K.; Mahamontri, C.; Narongruk, T.; Ketsa, S. Light during storage prevents loss of ascorbic acid, and increases glucose and fructose levels in Chinese kale (Brassica oleracea var. alboglabra). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 44, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, S.F.; Borge, G.I.A.; Solhaug, K.A.; Bengtsson, G.B. Effect of cold storage and harvest date on bioactive compounds in curly kale (Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2009, 51, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H.; Ichimura, K.; Oda, M. Changes in sugar content during cold acclimation and deacclimation of cabbage seedlings. Ann. Bot. 1996, 78, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dairi, M.; Pathare, P.B.; Al-Yahyai, R. Effect of postharvest transport and storage on color and firmness quality of tomato. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrón-Pereira, C.A.; Padrón-Pereira, G.M.; Montes-Hernández, A.I.; Oropeza-González, R.A. Determinación del Color en Epicarpio de Tomates (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.) con Sistema de Visión Computarizada Durante la Maduración. Available online: https://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0377-94242012000100008 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Zita, W.; Bressoud, S.; Glauser, G.; Kessler, F.; Shanmugabalaji, V. Chromoplast plastoglobules recruit the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway and contribute to carotenoid accumulation during tomato fruit maturation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ren, L.; Li, M.; Qian, J.; Fan, J.; Du, B. Effects of clove essential oil and eugenol on quality and browning control of fresh-cut lettuce. Food Chem. 2017, 214, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Murtaza, A.; Iqbal, A.; Fu, J.; Ali, S.W.; Iqbal, M.A.; Xu, X.; Pan, S.; Hu, W. Eugenol emulsions affect the browning processes, and microbial and chemical qualities of fresh-cut Chinese water chestnut. Food Biosci. 2020, 38, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artés-Hernández, F.; Miranda-Molina, F.D.; Klug, T.V.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Enrichment of glucosinolate and carotenoid contents of mustard sprouts by using green elicitors during germination. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 110, 104546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiger, K.; Linnanto, J.M.; Freiberg, A. Establishment of the Qy absorption spectrum of chlorophyll a extending to near-infrared. Molecules 2020, 25, 3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gómez, A.; Navarro-Martínez, A.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Active paper sheets including nanoencapsulated essential oils: A green packaging technique to control ethylene production and maintain quality in fresh horticultural products—A case study on flat peaches. Foods 2020, 9, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Chamorro, I.; Santos-Sánchez, G.; Martín, F.; Fernández-Pachón, M.S.; Hornero-Méndez, D.; Cerrillo, I. Evaluation of the impact of the ripening stage on the composition and antioxidant properties of fruits from organically grown tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Spanish varieties. Foods 2024, 13, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, P.; Sharma, A.; Singh, B.; Nagpal, A.K. Bioactivities of phytochemicals present in tomato. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romdhane, A.; Riahi, A.; Ujj, A.; Ramos-Diaz, F.; Marjanović, J.; Hdider, C. Comparative nutrient and antioxidant profile of high lycopene variety with hp genes and ordinary variety of tomato under organic conditions. Agronomy 2023, 13, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A.; Marchitelli, V.; Tamagnone, P.; Del Nobile, M.A. Use of active packaging for increasing ascorbic acid retention in food beverages. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, E502–E508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, O.T.; Valero, M.F.; Gómez-Tejedor, J.A.; Diaz, L. Performance of biodegradable active packaging in the preservation of fresh-cut fruits: A systematic review. Polymers 2024, 16, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (A) | ||||||

| Microorganism | Packaging | (°C) | b (°C−1) | (log CFU/g) | (log CFU/g) | (·) |

| Mesophiles | Active | 11.3 ± 0.69 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 2.22 ± 0.09 | 4.84 ± 0.24 | † |

| Control | 6.65 ± 1.16 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 2.39 ± 0.15 | 5.65 ± 0.29 | † | |

| Enterobacteria | Active | 10.27 ± 0.73 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 2.22 ± 0.06 | 4.50 ± 0.16 | † |

| Control | 10.75 ± 0.51 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 2.40 ± 0.08 | 6.49 ± 0.20 | † | |

| Yeasts | Active | −4.36 ± 4.66 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 2.32 ± 0.14 | 5.14 ± 0.96 | 0.49 ± 2.6 |

| Control | −1.09 ± 3.36 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 2.38 ± 0.15 | 5.53 ± 0.52 | † | |

| Moulds | Active | −3.66 ± 1.57 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 1.95 ± 0.03 | 3.71 ± 0.10 | 1.34 ± 0.4 |

| Control | −9.41 ± 6.58 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 2.00 ± 0.11 | 4.59 ± 0.81 | † | |

| Psychrophiles | Active | 19.76 ± 0.01 | 0.58 ± 0.01 | 2.60 ± 0.12 | ‡ | † |

| Control | 8.51 ± 0.96 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 2.58 ± 0.13 | 7.85 ± 0.46 | † | |

| (B) | ||||||

| Microorganism | Packaging | (°C) | b (°C−1) | (log CFU/g) | (log CFU/g) | (·) |

| Mesophiles | Active | −3.47 ± 0.88 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 3.43 ± 0.18 | 7.48 ± 0.31 | † |

| Control | −4.99 ± 0.93 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 3.48 ± 0.17 | 7.75 ± 0.18 | † | |

| Enterobacteria | Active | −4.59 ± 0.38 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 2.78 ± 0.14 | 8.29 ± 0.23 | † |

| Control | −3.47 ± 0.62 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 2.25 ± 0.17 | 7.53 ± 0.19 | † | |

| Yeasts | Active | −7.81 ± 1.09 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 2.66 ± 0.12 | 6.79 ± 0.16 | † |

| Control | −6.10 ± 0.78 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 2.62 ± 0.11 | 6.64 ± 0.12 | † | |

| Moulds | Active | −1.84 ± 0.86 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 2.53 ± 0.10 | 7.33 ± 0.38 | −0.35 ± 0.51 |

| Control | −4.30 ± 1.04 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 2.57 ± 0.11 | 7.52 ± 0.41 | † | |

| Psychrophiles | Active | −2.92 ± 1.03 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 3.92 ± 0.13 | 8.58 ± 0.26 | † |

| Control | 2.59 ± 0.67 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 4.32 ± 0.15 | 9.97 ± 0.30 | † | |

| (A) | ||||||

| SSC | pH | TA | ||||

| Control | Active | Control | Active | Control | Active | |

| Initial | 7.5 ± 0.2 Aa | 7.5 ± 0.2 Aa | 4.1 ± 0.0 Aa | 4.1 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa |

| 10 °C | ||||||

| 4 | 8.3 ± 0.5 Aa | 7.9 ± 1.0 Aa | 4.2 ± 0.0 Aa | 4.2 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.9 ± 0.1 Aa |

| 8 | 8.3 ± 1.5 Aa | 8.1 ± 0.2 Aa | 4.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 4.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.6 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa |

| 10 | 8.0 ± 1.0 Aa | 7.4 ± 0.4 Aa | 4.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 4.2 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa |

| 15 | 7.9 ± 1.1 Aa | 7.5 ± 0.7 Aa | 4.2 ± 0.0 Aa | 4.1 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.8 ± 0.2 Aa |

| 15 °C | ||||||

| 3 | 8.0 ± 1.2 Aa | 7.9 ± 1.3 Aa | 4.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 4.3 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.8 ± 0.1 Aa |

| 7 | 7.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 7.4 ± 0.8 Aa | 4.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 4.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.6 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa |

| 9 | 8.0 ± 0.7 Aa | 8.4 ± 0.6 Aa | 4.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 4.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa |

| 14 | 7.2 ± 0.3 Aa | 7.7 ± 0.3 Aa | 4.4 ± 0.0 Aa | 4.5 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.1 Aa |

| 22 °C | ||||||

| 1 | 7.3 ± 0.3 Ba | 8.2 ± 0.6 Aa | 4.3 ± 0.0 Aa | 4.3 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 2 | 8.7 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.4 ± 0.3 Ba | 4.4 ± 0.0 Aa | 4.2 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 5 | 8.5 ± 0.2 Aa | 7.8 ± 0.5 Ba | 4.3 ± 0.0 Aa | 4.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 8 | 7.1 ± 0.3 Aa | 5.1 ± 0.5 Ba | 4.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 4.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.2 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| (B) | ||||||

| SSC | pH | TA | ||||

| Control | Active | Control | Active | Control | Active | |

| Initial | 11.1 ± 0.1 Ab | 11.1 ± 0.1 Aab | 6.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 2 °C | ||||||

| 3 | 11.1± 0.2 Aa | 11.0 ± 0.1 Aab | 6.2 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 8 | 11.0 ± 0.1 Ab | 10.9 ± 0.1 Ab | 6.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 11 | 11.3 ± 0.2 Aa | 11.1 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 15 | 11.1 ± 0.2 Ab | 11.1 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 21 | 10.9 ± 0.2 Ab | 11.0 ± 0.1 Aab | 6.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 8 °C | ||||||

| 2 | 11.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 11.1 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.6 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 7 | 11.1 ± 0.1 Aa | 11.3 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 10 | 11.0 ± 0.2 Aa | 11.2 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 14 | 11.1 ± 0.1 Aa | 11.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.0 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 16 | 11.1± 0.2 Aa | 11.1± 0.1 Aa | 6.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 15 °C | ||||||

| 2 | 11.7± 0.3 Aa | 10.9 ± 0.1 Aa | 5.9 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.1 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.4 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 4 | 11.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 10.9 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.4 ± 0.2 Aa | 5.8 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.4 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 7 | 11.8 ± 0.2 Aa | 11.4± 0.3 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.0 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.4 ± 0.1 Aa |

| 9 | 11.7 ± 0.3 Aa | 11.6 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.0 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.4 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 22 °C | ||||||

| 1 | 11.2 ± 0.2 Aa | 11.3 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 2 | 11.4 ± 0.1 Aa | 11.3 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.6 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 3 | 10.9 ± 0.1 Aa | 11.2 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.3 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 4 | 11.1 ± 0.1 Aa | 10.9 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.2 ± 0.2 Aa | 6.2 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| 7 | 11.1± 0.1 Aa | 11.0± 0.1 Aa | 6.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 6.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.0 Aa |

| (A) | |||||||||||||

| Initial | 10 °C | 15 °C | 22 °C | ||||||||||

| 4 | 8 | 10 | 15 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 14 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 8 | ||

| Chroma Control | 97.3 ± 6.6 Aa | 96.1 ± 8.7 Aa | 103.9 ± 7.2 Aa | 106.2 ± 7.0 Aa | 105.4 ± 4.9 Aa | 97.7 ± 7.8 Aa | 96.8 ± 7.1 Aa | 103.1 ± 4.2 Aa | 99.2 ± 3.5 Aa | 89.3 ± 8.9 Aa | 108.7 ± 8.4 Aa | 83.7 ± 7.0 Aa | 111.0 ± 6.1 Aa |

| Active | 97.3 ± 6.6 Aa | 99.3 ± 9.8 Aa | 102.2 ± 7.2 Aa | 101.8 ± 7.2 Aa | 101.2 ± 6.1 Aa | 97.4 ± 8.5 Aa | 105.3 ± 6.9 Aa | 104.0 ± 7.3 Aa | 102.8 ± 6.7 Aa | 96.0 ± 9.9 Aa | 114.1 ± 7.0 Aa | 83.2 ± 5.1 Aa | 107.4 ± 6.1 Aa |

| Hue Control | 57.9 ± 3.5 Aa | 54.2 ± 3.9 Aa | 54.6 ± 3.3 Aa | 54.0 ± 3.8 Aa | 52.4 ± 2.9 Aa | 51.9 ± 4.1 Aa | 48.8 ± 2.3 Aa | 48.4 ± 3.3 Aa | 44.3 ± 2.0 Aa | 52.3 ± 6.9 Aa | 39.8 ± 4.2 Aa | 37.2 ± 2.1 Aa | 35.0 ± 1.8 Aa |

| Active | 57.9 ± 3.5 Aa | 54.9 ± 2.9 Aa | 54.4 ± 3.8 Aa | 52.6 ± 3.3 Aa | 54.8 ± 4.2 Aa | 54.8 ± 4.5 Aa | 51.2 ± 2.9 Aa | 49.9 ± 3.6 Aa | 46.2 ± 2.5 Aa | 56.7 ± 6.9 Aa | 42.0 ± 4.2 Aa | 39.2 ± 3.7 Aa | 34.4 ± 2.1 Aa |

| Colour index Control | 17.6 ± 2.7 Aa | 21.8 ± 2.8 Aa | 24.1 ± 1.4 Aa | 25.9 ± 3.4 Aa | 28.4 ± 1.2 Aa | 21.8 ± 2.8 Aa | 24.1 ± 1.4 Aa | 25.9 ± 3.4 Aa | 28.4 ± 1.2 Aa | 22.7 ± 5.1 Aa | 28.1 ± 3.0 Aa | 57.0 ± 2.0 Aa | 43.4 ± 1.6 Aa |

| Active | 17.6 ± 2.7 Aa | 19.9 ± 2.7 Aa | 22.8 ± 2.3 Aa | 24.1 ± 3.2 Aa | 27.5 ± 2.3 Aa | 19.9 ± 2.7 Aa | 22.8 ± 2.3 Aa | 24.1 ± 3.2 Aa | 27.5 ± 2.3 Aa | 19.8 ± 4.5 Aa | 25.8 ± 2.5 Aa | 51.5 ± 3.3 Aa | 43.7 ± 1.4 Aa |

| a/b Control | 0.6 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.8 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.8 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.9 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.9 ± 0.1 Aa | 1.0 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.8 ± 0.2 Aa | 1.3 ± 0.1 Aa | 1.5 ± 0.1 Aa | 1.6 ± 0.1 Aa |

| Active | 0.6 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.8 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.8 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.8 ± 0.1 Aa | 1.0 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.2 Aa | 1.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 1.4 ± 0.1 Aa | 1.7 ± 0.1 Aa |

| (a/b)2 Control | 0.4 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.6 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.6 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.8 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.8 ± 0.2 Aa | 1.1 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.3 Aa | 1.7 ± 0.2 Aa | 2.0 ± 0.1 Aa | 2.4 ± 0.1 Aa |

| Active | 0.4 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.6 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 0.7 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.9 ± 0.2 Aa | 0.5 ± 0.2 Aa | 1.4 ± 0.2 Aa | 1.8 ± 0.2 Aa | 2.6 ± 0.1 Aa |

| Total carotenoids (mg kg−1) Control | 53.9 ± 6.5 Aa | 54.0 ± 8.0 Aa | 5.9 ± 7.7 Aa | 54.6 ± 2.0 Aa | 50.7 ± 8.4 Aa | 52.7 ± 5.5 Aa | 65.0 ± 7.7 Aa | 74.0 ± 2.2 Aa | 73.1 ± 3.8 Aa | 50.7 ± 5.2 Aa | 56.0 ± 6.4 Aa | 68.8 ± 6.7 Aa | 72.9 ± 4.4 Aa |

| Active | 53.9 ± 6.5 Aa | 53.7 ± 4.6 Aa | 55.7 ± 2.5 Aa | 55.6 ± 3.4 Aa | 55.5 ± 6.2 Aa | 53.9 ± 4.2 Aa | 67.6 ± 2.1 Aa | 73.5 ± 7.3 Aa | 71.3 ± 7.6 Aa | 46.4 ± 5.1 Aa | 63.3 ± 6.5 Aa | 68.4 ± 5.6 Aa | 71.7 ± 2.5 Aa |

| (B) | |||||||||||||

| Initial | 2 °C | 8 °C | |||||||||||

| 3 | 8 | 11 | 15 | 21 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 14 | 16 | ||||

| Chroma Control | 26.7 ± 6.0 Aa | 19.8 ± 4.1 Aa | 27.5 ± 8.5 Aa | 16.8 ± 6.6 Aa | 27.9 ± 8.3 Aa | 24.7 ± 8.4 Aa | 20.5 ± 4.4 Aa | 17.5 ± 4.7 Aa | 22.5 ± 8.9 Aa | 16.1 ± 3.5 Aa | 22.1 ± 6.4 Aa | ||

| Active | 26.7 ± 6.0 Aa | 19.8 ± 7.9 Aa | 18.0 ± 4.8 Aa | 19.9 ± 6.6 Aa | 23.5 ± 8.7 Aa | 28.4 ± 9.8 Aa | 21.4 ± 5.1 Aa | 17.5 ± 4.0 Aa | 16.0 ± 4.7 Aa | 26.9 ± 6.1 Aa | 22.5 ± 7.8 Aa | ||

| Hue Control | 128.6 ± 2.3 Aa | 128.5 ± 2.7 Aa | 129.4 ± 10.7 Aa | 130.3 ± 3.5 Aa | 129.7 ± 11.9 Aa | 124.0 ± 6.2 Aa | 135.2 ± 28.1 Aa | 130.2 ± 2.2 Aa | 126.0 ± 3.8 Ab | 129.2 ± 3.4 Ab | 127.2 ± 5.4 Ab | ||

| Active | 128.6 ± 2.3 Aa | 132.0 ± 6.9 Aa | 131.5 ± 4.3 Aa | 128.4 ± 4.8 Aa | 126.1 ± 3.1 Aa | 121.1 ± 8.7 Aa | 136.5 ± 25.2 Aa | 129.8 ± 3.4 Aa | 130.0 ± 3.8 Aa | 124.3 ± 3.2 Aa | 127.2 ± 5.5 Aa | ||

| Total colour difference Control | 9.8 ± 5.2 Aa | 22.4 ± 6.7 Aa | 19.8 ± 5.6 Aa | 23.1 ± 9.2 Aa | 16.7 ± 8.2 Aa | 18.5 ± 7.0 Aa | 16.6 ± 7.3 Aa | 23.6 ± 7.0 Aa | 20.8 ± 8.9 Aa | 21.9 ± 8.9 Aa | 12.8 ± 7.1 Aa | ||

| Active | 9.8 ± 5.2 Aa | 19.7 ± 6.4 Aa | 20.6± 6.8 Aa | 17.4 ± 10.4 Aa | 15.8 ± 7.2 Aa | 16.5 ± 8.1 Aa | 14.8 ± 9.8 Aa | 21.7 ± 7.9 Aa | 22.6 ± 9.9 Aa | 13.4 ± 7.3 Aa | 17.7 ± 9.4 Aa | ||

| Yellowness Index Control | 62.7 ± 13.0 Aa | 82.9 ± 18.7 Aa | 92.7 ± 24.9 Aa | 65.8 ± 20.0 Aa | 85.6 ± 23.7 Aa | 86.0 ± 21.4 Aa | 65.7 ± 12.2 Ab | 71.4 ± 12.2 Ab | 85.6 ± 15.6 Aa | 62.5 ± 13.8 Ac | 66.0 ± 23.5 Ab | ||

| Active | 62.7± 13.0 Aa | 62.6 7 ± 23.4 Aa | 65.3 ± 18.8 Aa | 66.8 ± 9.8 Aa | 74.3 ± 16.3 Aa | 74.8 ± 19.6 Aa | 63.4 ± 12.1 Ab | 68.0 ± 14.8 Ab | 63.4 ± 16.3 Ab | 85.1 ± 15.5 Aa | 79.5 ± 26.6 Ab | ||

| Total chlorophylls (mg kg−1) Control | 2026.1 ± 71.1 Aa | 2065.0 ± 323.4 Aa | 2079.0 ± 120.4 Aa | 1867.9± 122.9 Aa | 1845.9 ± 113.1 Aa | 2068.0 ± 144.3 Aa | 192.6 ± 203.2 Aa | 2024.7 ± 135.7 Aa | 2194.2 ± 138.4 Aa | 1863.7 ± 74.2 Aa | 1999.6 ± 155.8 Aa | ||

| Active | 2026.1 ± 71.1 Aa | 2144.5 ± 107.9 Aa | 1883.2 ± 138.2 Aa | 2385.1 ± 241.7 Aa | 1941.3 ± 92.2 Aa | 2040.0 ± 90.3 Aa | 2040.0 ± 42.5 Aa | 1832.1 ± 81.1 Aa | 1984.5 ± 243.2 Aa | 2072.6 ± 83.9 Aa | 2017.9 ± 97.3 Aa | ||

| 15 °C | 22 °C | ||||||||||||

| Days | 2 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 7 | ||||

| Chroma Control | 21.5 ± 4.5 Aa | 11.5 ± 4.7 Aa | 12.3 ± 5.7 Aa | 18.9 ± 4.5 Aa | 20.2 ± 5.5 Aa | 17.0 ± 5.0 Aa | 12.3 ± 5.7 Aa | 18.9 ± 4.5 Aa | 18.3 ± 6.4 Aa | ||||

| Active | 28.9 ± 6.5 Aa | 131.8 ± 4.6 Aa | 11.5 ± 4.0 Aa | 31.6 ± 8.2 Aa | 16.5 ± 4.2 Aa | 23.6 ± 7.3 Aa | 11.5 ± 4.7 Aa | 32.7 ± 4.6 Aa | 18.9 ± 7.8 Aa | ||||

| Hue Control | 129.9 ± 3.2 Aba | 131.8 ± 2.2 Aa | 128.9 ± 2.4 Ab | 129.9 ± 2.9 Ab | 133.3 ± 6.1 Aa | 128.3 ± 7.5 Aa | 128.9 ± 2.4 Aa | 129.9 ± 2.9 Aa | 125.9 ± 5.4 Aa | ||||

| Active | 128.2 ± 3.6 Ab | 118.4 ± 4.6 Ac | 131.1 ± 3.4 Aa | 126.8 ± 4.5 Ab | 133.4 ± 2.7 Aa | 127.5 ± 3.4 Aa | 131.8 ± 2.2 Aa | 118.4 3.3 Aa | 125.8 ± 5.5 Aa | ||||

| Total colour difference Control | 9.5 ± 5.3 Ba | 57.2 ± 7.0 Aa | 42.1 ± 9.6 Ba | 18.3 ± 7.4 Aa | 16.4 ± 7.1 Aa | 20.5 ± 7.0 Aa | 42.1 ± 9.9 Aa | 18.3 ± 7.4 Aa | 16.8 ± 7.1 Aa | ||||

| Active | 12.3 ± 4.8 Aa | 14.5 ± 5.8 Ba | 48.4 ± 7.9 Aa | 10.2 ± 5.5 Ba | 16.3 ± 5.7 Aa | 14.2 ± 5.6 Aa | 57.2 ± 7.0 Aa | 14.5 ± 5.8 Aa | 32.2 ± 9.4 Aa | ||||

| Yellow Control | 52.5 ± 14.8 Aa | 81.4 ± 12.2 Aa | 73.6 ± 15.3 Aa | 50.5 ± 10.5 Aa | 40.7 ± 15.6 Aa | 60.1 ± 10.4 Aa | 73.6 ± 15.3 Aa | 50.5 ± 10.5 Aa | 69.5 ± 23.5 Aa | ||||

| Active | 69.9 ± 15.1 Aa | 132.7 ± 19.3 Aa | 73.7 ± 14.8 Aa | 67.8 ± 16.4 Aa | 47.7 ± 12.1 Aa | 70.8 ± 17.6 Aa | 81.4 ± 12.2 Aa | 132.7 ± 19.3 Aa | 100.8 ± 26.6 Aa | ||||

| Total chlorophylls Control | 2082.7 ± 151.7 Aa | 1985.8 ± 252.2 Aa | 1792.7 ± 49.8 Aa | 1980.2 ± 180.3 Aa | 2152.1 ± 128.9 Aa | 2001.7 ± 259.1 Aa | 2041.7± 152.4 Aa | 1930.5 ± 76.9 Aa | 2135.4 ± 31.8 Aa | ||||

| Active | 1661.4 344.2 Aa | 2080.9 ± 457.2 Aa | 1850.6 ± 39.3 Aa | 1882.8 ± 27.9 Aa | 2122.8 ± 169.7 Aa | 2257.8 ± 169.8 Aa | 1844.0 ± 24.1 Aa | 1945.4 ± 43.1 Aa | 2403.7 ± 79.9 Aa | ||||

| (A) | ||||||

| Total Phenolic Content (mg kg−1 FW) | Antioxidant Activity (mmol kg−1 FW) | Vitamin C (mg kg−1 FW) | ||||

| Control | Active | Control | Active | Control | Active | |

| Initial | 324.3 ± 24.3 Aa | 324.3 ± 24.3 Aa | 2.6 ± 0.4 Aa | 2.6 ± 0.4 Aa | 291.9 ± 77.7 Aa | 291.9 ± 77.7 Aa |

| 10 °C | ||||||

| 4 | 332.2 ± 49.8 Aa | 321.7 ± 14.4 Aa | 3.7 ± 0.5 Aa | 3.7 ± 0.2 Aa | 252.5 ± 62.2 Aa | 251.3 ± 30.6 Aa |

| 8 | 314.5 ± 2.5 Aa | 304.6 ± 9.6 Aa | 3.5 ± 0.3 Aa | 3.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 254.2 ± 56.8 Aa | 284.1 ± 37.6 Aa |

| 10 | 327.2 ± 2.9 Aa | 346.6 ± 47.2 Aa | 3.7 ± 0.3 Aa | 3.5 ± 0.4 Aa | 310.0 ± 70.8 Aa | 313.5 ± 55.1 Aa |

| 15 | 350.7 ± 31.8 Aa | 295.2 ± 12.0 Aa | 3.5 ± 0.4 Aa | 4.2 ± 0.4 Aa | 273.9 ± 24.4 Aa | 339.1 ± 17.5 Aa |

| 15 °C | ||||||

| 3 | 371.0 ± 29.3 Aa | 417.1 ± 62.2 Aa | 2.5 ± 0.1 Aa | 2.5 ± 0.3 Aa | 194.7 ± 17.2 Aa | 290.4 ± 10.3 Aa |

| 7 | 383.4 ± 36.4 Aa | 366.1 ± 33.6 Aa | 2.9 ± 0.3 Aa | 2.6 ± 0.1 Aa | 273.1 ± 41.1 Aa | 243.7 ± 40.8 Aa |

| 9 | 389.3 ± 26.5 Aa | 403.8 ± 60.1 Aa | 2.6 ± 0.1 Aa | 2.6 ± 0.2 Aa | 298.7 ± 47.1 Aa | 310.5 ± 18.4 Aa |

| 14 | 419.1 ± 62.3 Aa | 403.2 ± 50.4 Aa | 2.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 2.6 ± 0.2 Aa | 264.8 ± 19.6 Aa | 286.4 ± 44.8 Aa |

| 22 °C | ||||||

| 1 | 326.1 ± 34.2 Aa | 324.6 ± 81.7 Aa | 2.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 2.1 ± 0.2 Aa | 165.2 ± 58.6 Aa | 151.1 ± 11.1 Aa |

| 2 | 310.8 ± 17.2 Aa | 334.7 ± 25.8 Aa | 2.3 ± 0.2 Aa | 2.2 ± 0.1 Aa | 313.7 ± 35.7 Aa | 236.7 ± 62.7 Aa |

| 5 | 396.0 ± 36.4 Aa | 324.2 ± 28.8 Aa | 2.4 ± 0.2 Aa | 2.4 ± 0.1 Aa | 182.9 ± 30.3 Aa | 215.8 ± 17.0 Aa |

| 8 | 382.2 ± 12.4 Aa | 379.4 ± 63.5 Aa | 2.4 ± 0.1 Aa | 2.4 ± 0.2 Aa | 191.0 ± 27.8 Aa | 228.6 ± 6.0 Aa |

| (B) | ||||||

| Total Phenolic Content (mg kg−1 FW) | Antioxidant Activity (mmol kg−1 FW) | Vitamin C (mg kg−1 FW) | ||||

| Control | Active | Control | Active | Control | Active | |

| Initial | 1471.6 ± 19.4 Aa | 1471.6 ± 224.2 Aa | 3.3 ± 0.2 Aa | 3.3 ± 0.2 Aa | 193.6 ± 7.1 Aa | 193.6 ± 7.1 Aa |

| 2 °C | ||||||

| 3 | 1252.5 ± 224.2 Aa | 1304.9 ± 95.5 Aa | 3.1 ± 0.4 Aa | 3.6 ± 0.2 Aa | 183.9 ± 18.8 Aa | 254.5 ± 10.0 Aa |

| 8 | 1023.8 ± 114.6 Aa | 1032.3 ± 33.8 Aa | 2.9 ± 0.2 Aa | 2.8 ± 0.2 Aa | 264.6 ± 16.1 Aa | 294.8 ± 11.0 Aa |

| 11 | 902.5 ± 115.8 Aa | 1750.5 ± 165.5 Aa | 3.5 ± 0.7 Aa | 3.9 ± 0.1 Aa | 226.3 ± 16.8 Aa | 260.8 ± 14.5 Aa |

| 15 | 1591.5 ± 36.4 Aa | 924.9 ± 215.5 Aa | 3.7 ± 0.6 Aa | 2.7 ± 0.2 Aa | 230.6 ± 14.9 Aa | 265.6 ± 35.9 Aa |

| 21 | 1494.3 ± 221.4 Aa | 1190.2 ± 126.0 Aa | 3.2 ± 0.2 Aa | 3.6 ± 0.2 Aa | 207.8 ± 12.8 Aa | 243.2 ± 46.0 Aa |

| 8 °C | ||||||

| 2 | 1298.1 ± 206.5 Aa | 1423.2 ± 9.1 Aa | 2.9 ± 0.1 Aa | 2.6 ± 0.1 Aa | 182.8 ± 5.5 Aa | 263.1 ± 35.1 Aa |

| 7 | 1548.0 ± 101.0 Aa | 1098.8 ± 76.3 Aa | 2.9 ± 0.3 Aa | 2.9 ± 0.1 Aa | 233.9 ± 27.8 Aa | 226.7 ± 18.2 Aa |

| 10 | 1098.4 ± 30.1 Aa | 993.3 ± 35.4 Aa | 3.5 ± 0.1 Aa | 3.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 274.3 ± 46.4 Aa | 254.2 ± 24.7 Aa |

| 14 | 874.1 ± 131.1 Aa | 1165.7 ± 104.0 Aa | 3.8 ± 0.0 Aa | 3.4 ± 0.2 Aa | 200.4 ± 21.7 Aa | 288.8 ± 25.5 Aa |

| 16 | 1167.2 ± 141.1 Aa | 1263.9 ± 17.2 Aa | 2.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 3.1 ± 0.2 Aa | 205.4 ± 22.9 Aa | 243.3 ± 12.8 Aa |

| 15 °C | ||||||

| 2 | 1133.7 ± 34.3 Aa | 1200.6 ± 104.2 Aa | 3.1 ± 0.6 Aa | 3.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 410.3 ± 51.8 Aa | 127.1 ± 12.8 Aa |

| 4 | 1280.3 ± 209.6 Aa | 961.5 ± 172.9 Aa | 3.4 ± 0.1 Aa | 2.7 ± 0.2 Aa | 185.2 ± 60.3 Aa | 221.1 ± 27.7 Aa |

| 7 | 1394.6 ± 131.2 Aa | 1554.8 ± 67.0 Aa | 2.7 ± 0.2 Aa | 3.0 ± 0.0 Aa | 177.8 ± 9.0 Aa | 171.7 ± 19.2 Aa |

| 9 | 926.0 ± 210.3 Aa | 1580.4 ± 94.8 Aa | 2.7 ± 0.1 Aa | 3.7 ± 0.2 Aa | 320.4 ± 31.7 Aa | 412.4 ± 44.3 Aa |

| 22 °C | ||||||

| 1 | 1514.3 ± 111.5 Aa | 1524.3 ± 251.3 Aa | 3.8 ± 0.3 Aa | 3.8 ± 0.7 Aa | 297.4 ± 32.9 Aa | 250.4 ± 31.8 Aa |

| 2 | 1662.5 ± 63.5 Aa | 1656.3 ± 54.7 Aa | 3.7 ± 0.2 Aa | 4.0 ± 0.1 Aa | 244.2 ± 24.1 Aa | 379.4 ± 21.5 Aa |

| 3 | 1504.9 ± 180.0 Aa | 1495.6 ± 69.2 Aa | 3.7 ± 0.2 Aa | 3.4 ± 0.2 Aa | 411.1 ± 59.6 Aa | 326.7 ± 40.8 Aa |

| 4 | 1351.4 ± 132.0 Aa | 1575.3 ± 161.0 Aa | 3.3 ± 0.2 Aa | 3.6 ± 0.2 Aa | 339.4 ± 48.5 Aa | 371.1 ± 36.2 Aa |

| 7 | 1806.8 ± 435.9 Aa | 1582.3 ± 49.4 Aa | 3.6 ± 0.8 Aa | 3.1 ± 0.8 Aa | 162.4 ± 9.7 Aa | 225.0 ± 3.3 Aa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Navarro-Martínez, A.; Piñeros-Castro, Y.; Garre, A.; López-Gómez, A.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Effects of Active Paper Sheets on the Quality of Cherry Tomatoes and Kale During Storage. Foods 2025, 14, 4225. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244225

Navarro-Martínez A, Piñeros-Castro Y, Garre A, López-Gómez A, Martínez-Hernández GB. Effects of Active Paper Sheets on the Quality of Cherry Tomatoes and Kale During Storage. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4225. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244225

Chicago/Turabian StyleNavarro-Martínez, Alejandra, Yineth Piñeros-Castro, Alberto Garre, Antonio López-Gómez, and Ginés Benito Martínez-Hernández. 2025. "Effects of Active Paper Sheets on the Quality of Cherry Tomatoes and Kale During Storage" Foods 14, no. 24: 4225. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244225

APA StyleNavarro-Martínez, A., Piñeros-Castro, Y., Garre, A., López-Gómez, A., & Martínez-Hernández, G. B. (2025). Effects of Active Paper Sheets on the Quality of Cherry Tomatoes and Kale During Storage. Foods, 14(24), 4225. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244225