3.1. Dataset

After successfully obtaining the ForestFoodKG dataset, we conduct a comprehensive and in-depth statistical analysis of it. As shown in

Figure 4, the ForestFoodKG dataset encompasses ten categories, including forest vegetables, forest fruits, forest teas, forest bee products, forest meats, forest spices, and forest medicines, providing a comprehensive overview of forest food resources. Despite the rich variety and extensive coverage of categories, the structure of the dataset exhibits a certain degree of imbalance. Among these categories, forest vegetables rank first with a proportion of 14.00%, indicating their significant position within forest food resources. Following closely are forest teas, forest fruits, Forest bee products, forest spices, forest meats, and forest medicines, each with a share exceeding 10%, collectively forming an important pillar of the forest food industry. In contrast, forest nuts have the lowest proportion among all categories, revealing their relative scarcity in forest food resources.

In addition, we conducted a detailed taxonomic analysis of the collected forest food resources, encompassing various levels of classification, including kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. In this study, we conduct a systematic taxonomic analysis of the collected forest food resources, covering all classification levels from kingdom to species, including kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. According to the ForestFoodKG records, the forest food resources involve three major biological kingdoms. Among these, the plant kingdom holds an absolute dominance, with a total of 1011 species, accounting for 84.9% of the entire dataset. In contrast, the fungal kingdom represents the smallest proportion, with only 16 species, accounting for 1.3%. The animal kingdom includes 164 species, making up 14.8% of the dataset.

In the ForestFoodKG, the records encompass 24 different biological phyla. Among them, the phylum Angiosperms ranks first with a frequency of 941 occurrences, significantly higher than that of other phyla. Following closely is the phylum Chordata, with 113 occurrences. The remaining phyla have relatively low frequencies in the dataset. We conduct a statistical analysis of the distribution of phyla, and the results show that the number of species in Angiosperms and Chordata is significantly higher than in other groups. This finding indicates that Angiosperms and Chordata dominate the classification of forest foods.

The dataset is categorized into 39 different biological classes, ranging from plant classes such as Magnoliopsida and Pinopsida to fungal classes like Basidiomycetes and Agaricomycetes. Among these classes, Magnoliopsida and Dicotyledoneae are particularly prominent, occupying a significant proportion. These two classes play a key role in the diversity of forest foods, highlighting the richness and complexity of the plant kingdom. To more clearly depict the distribution characteristics of these classes, we further describe the distribution of several major classes.

The ForestFoodKG records a total of 167 different biological orders, encompassing various classifications such as Gentianales, Asterales, Erythropalales, Cucurbitales, Saxifragales, and Campanulales, among others. These classifications reflect the wide distribution of forest foods within biodiversity.

3.2. Data Records

The ForestFoodKG compiles 1191 detailed records, each presented accurately in Chinese, with precise separation by blank lines to ensure high readability. Given the scarcity of information on forest foods, this compilation represents the largest and most unique dataset of its kind currently known. An overview of the relevant fields and content can be found in

Table 5.

Table 6 provides examples of two records from the dataset.

The taxonomy of forest foods and their rich nutritional component information provide extensive application potential for data modeling in artificial intelligence. These data can be utilized for personalized health analysis and nutritional recommendations, monitoring food safety risks, assessing medicinal value, analyzing market trends, optimizing agricultural and forestry management, and supporting the evaluation of ecosystem services. Furthermore, this information can aid in the development of educational tools to enhance public awareness and consumption of forest foods, thereby promoting sustainable development and the rational utilization of resources.

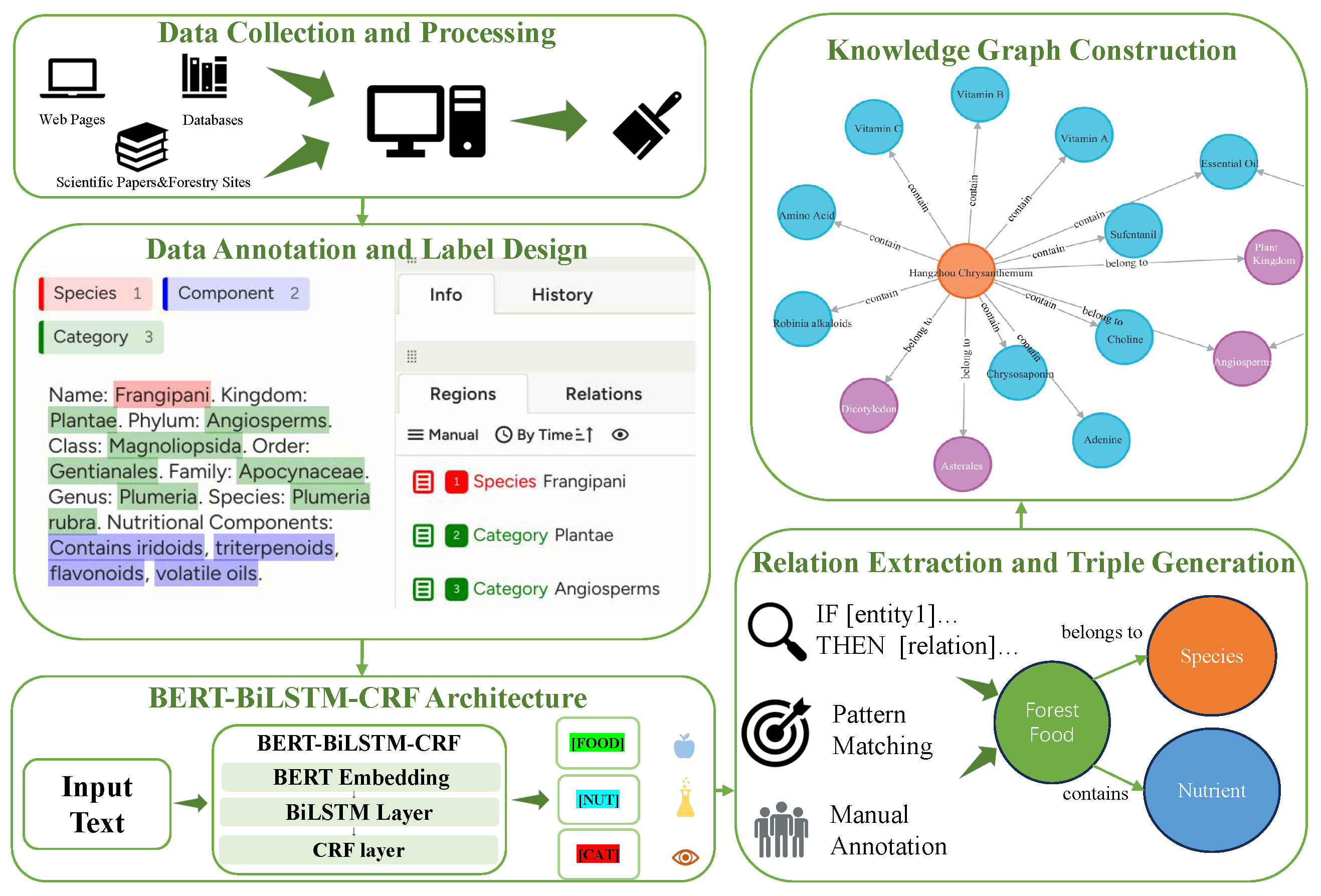

3.3. Experimental Setup

All models were trained on the manually annotated ForestFood dataset using a consistent experimental protocol. For the BERT-Softmax and BERT-BiLSTM-Softmax architectures, we employed the standard cross-entropy loss function, while the BERT-BiLSTM-CRF model was optimized using CRF loss, which explicitly models label transition constraints. To mitigate overfitting, we implemented an early stopping mechanism based on validation set performance, with patience set to 5 epochs. The training configuration utilized a fixed batch size of 32 across all experiments, with models trained for a maximum of 20 epochs. Hyperparameter optimization, particularly for the learning rate, was conducted through systematic grid search to ensure optimal performance.

The specific hyperparameter configurations employed in our BERT-BiLSTM-CRF model are detailed in

Table 7, ensuring full reproducibility of our experimental results.

3.4. Results and Discussion

The foundation for constructing a high-quality knowledge graph lies in the accurate identification of entities from unstructured text, which represents the core objective of the NER task. As the initial and most critical step in the pipeline, the performance of the NER model directly determines the completeness and correctness of all subsequent entities and relationships in ForestFoodKG-KG. To systematically evaluate entity recognition capabilities in the forest food domain, we compared three mainstream architectures: BERT-Softmax, BERT-BiLSTM-Softmax, and BERT-BiLSTM-CRF. After 20 training epochs, the performance metrics of each model on the test set are presented in

Table 8.

Experimental results demonstrate that BERT-BiLSTM-Softmax achieved the best performance with an F1-score of 0.9135, while BERT-BiLSTM-CRF attained the highest recall rate of 0.8944. This finding challenges the conventional preference for CRF-based architectures in NER tasks, suggesting that in specialized domains with limited training data, the additional complexity introduced by CRF layers may not yield proportional performance benefits. Notably, all BiLSTM-enhanced models significantly outperformed the baseline BERT-Softmax, confirming the importance of sequence modeling for handling complex entity structures in the forest food domain.

This study provides important references for knowledge graph construction in ecological and agricultural domains. The experimental results reveal a crucial trade-off in model selection: BERT-BiLSTM-Softmax offers more balanced overall performance, while BERT-BiLSTM-CRF demonstrates advantages in entity coverage. We hypothesize that the CRF architecture might realize its full potential with larger training datasets, representing a key direction for future investigation. This research validates the feasibility of constructing domain-specific knowledge graphs with limited annotated resources, establishing a solid foundation for downstream applications such as dietary recommendation systems and ecological research.