The Effect of 2′-Fucosyllactose on Gut Health in Aged Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

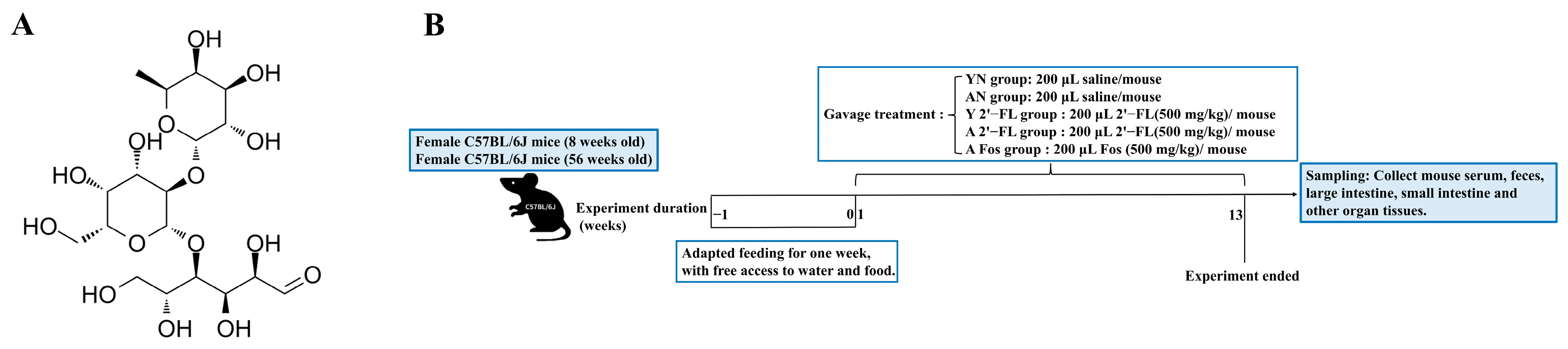

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Animals

2.3. Animal Experimental Procedures

2.4. Indicator Detection

2.4.1. Measurement of Fecal Water Content and pH Value

2.4.2. Intestinal Permeability Assessment

2.4.3. Serum Antibody Detection

2.4.4. Detection of Cytokine Levels

2.4.5. Histological Analysis of Tissues

2.4.6. RT-qPCR

2.4.7. Western Blot

2.5. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

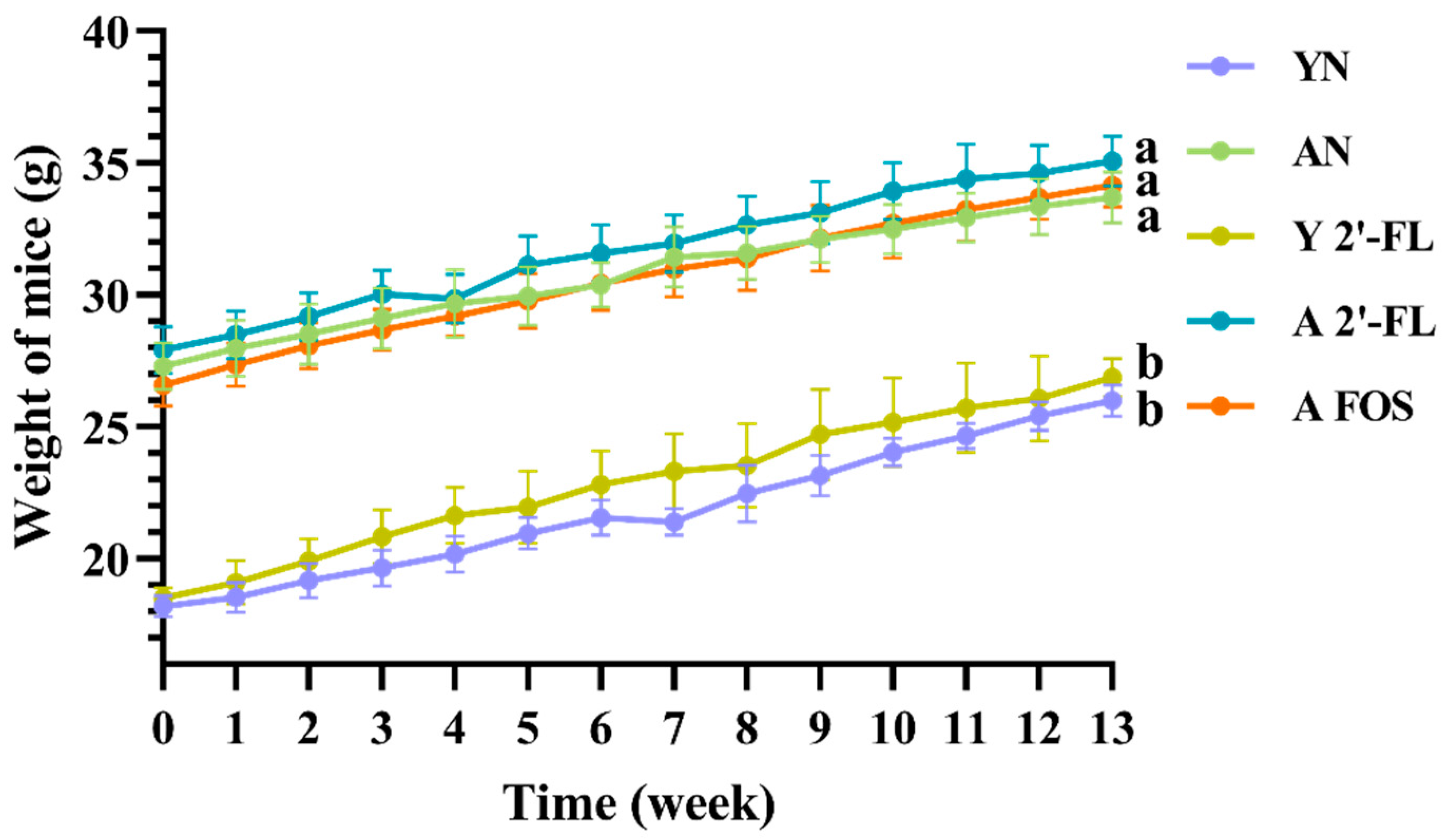

3.1. Effects of 2′-FL on Body Weight and Physiological Status of Mice in Each Group

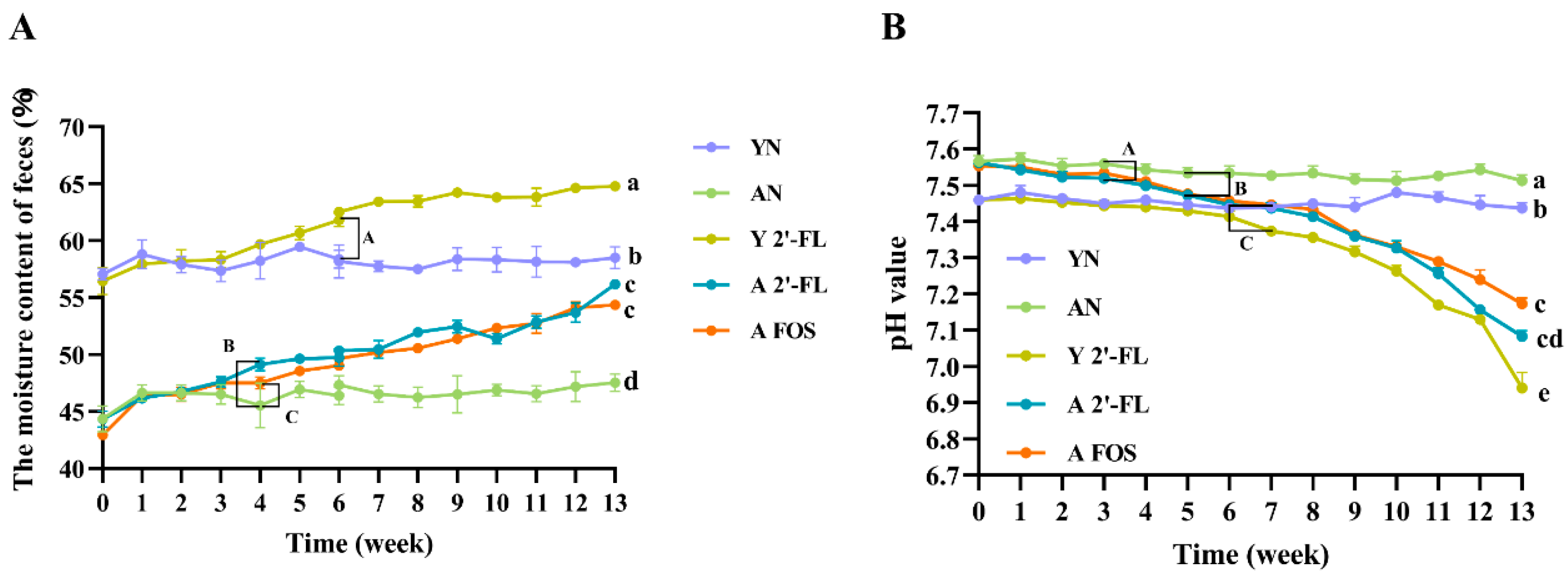

3.2. Effects of 2′-FL on Fecal Moisture and pH Values in Mice of Each Group

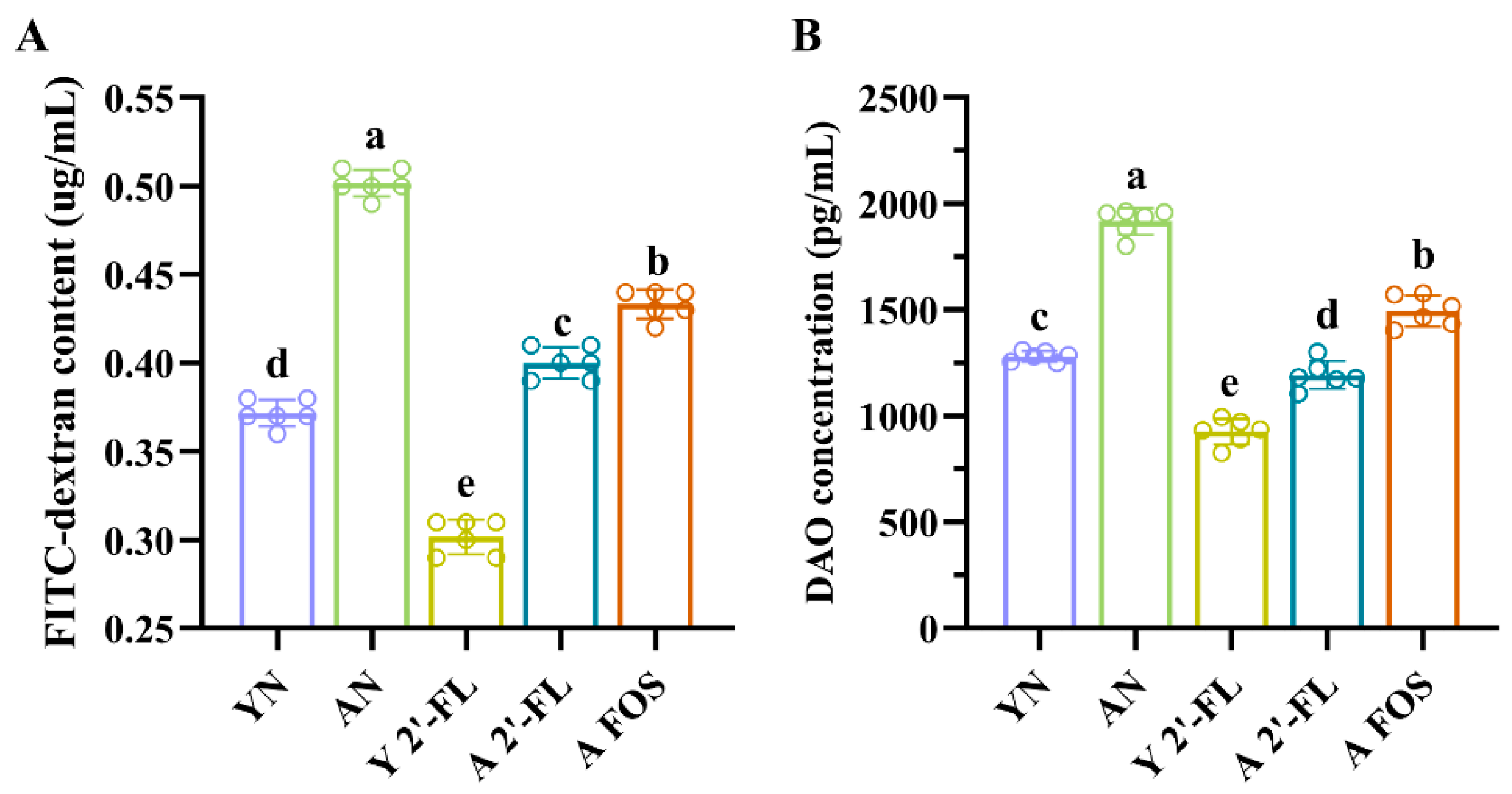

3.3. Effects of 2′-FL on Intestinal Permeability in Mice of Each Group

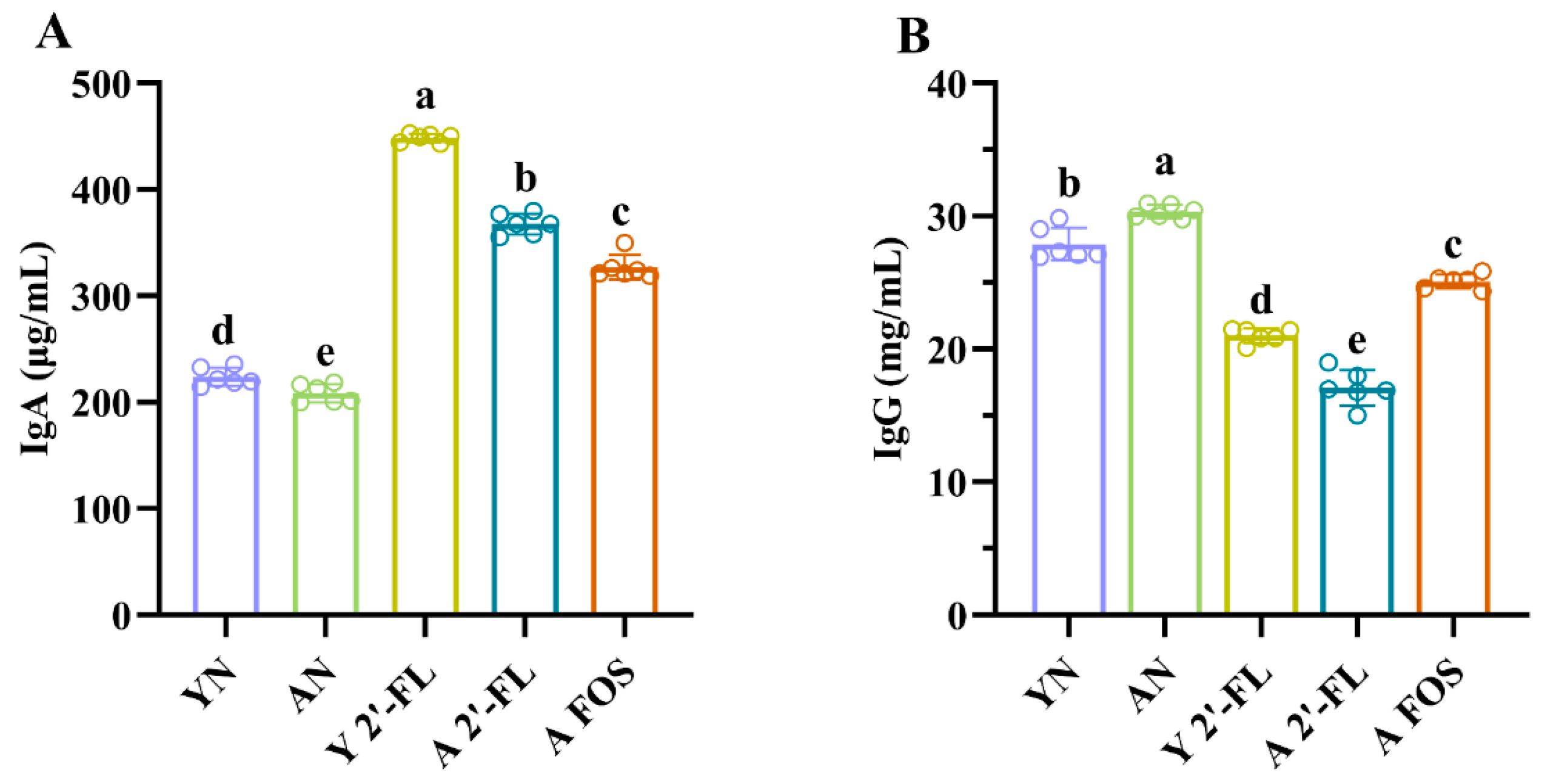

3.4. Effects of 2′-FL on Antibody Levels in Mice of Each Group

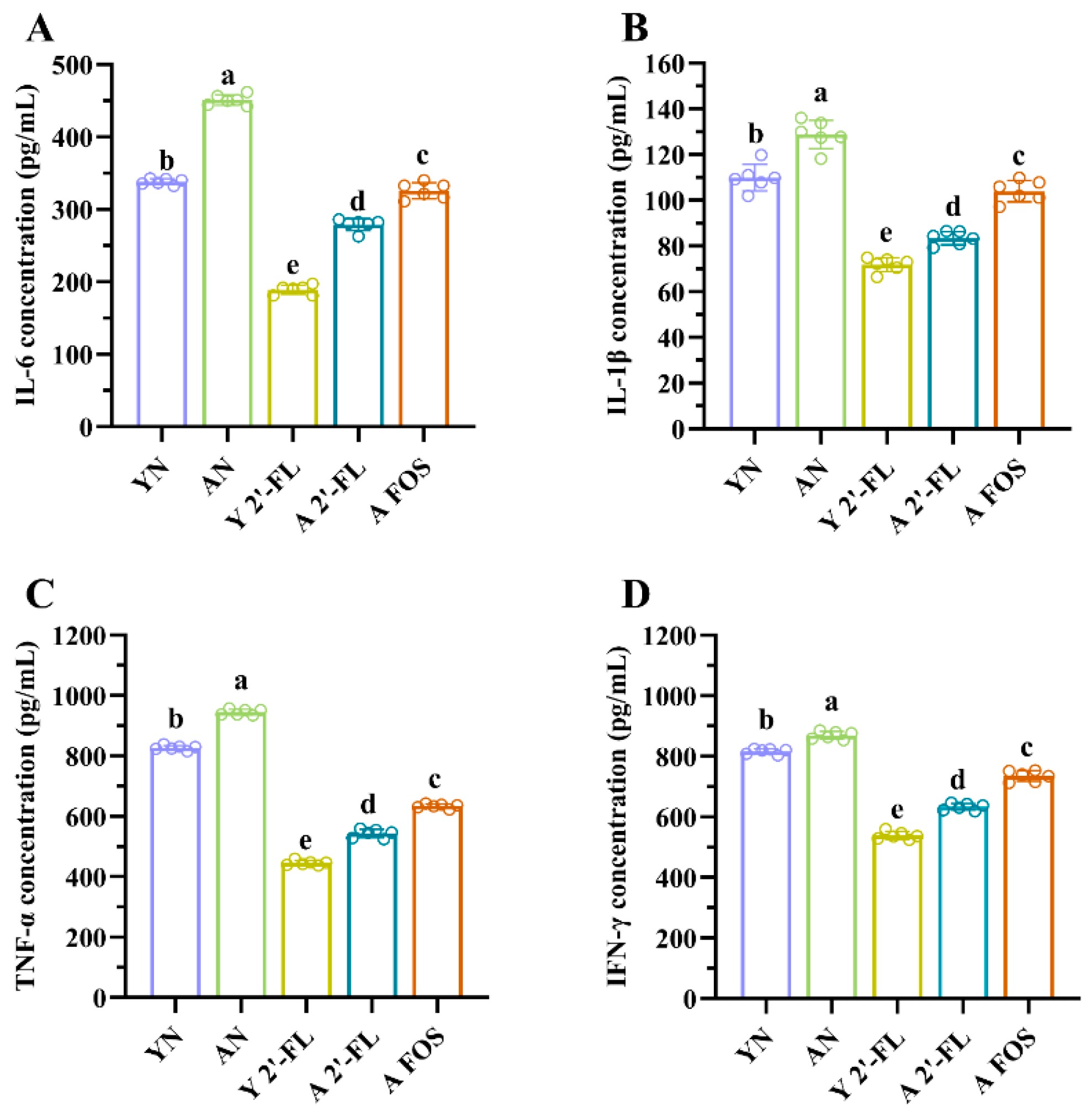

3.5. Effects of 2′-FL on Cytokine Levels in Mice of Each Group

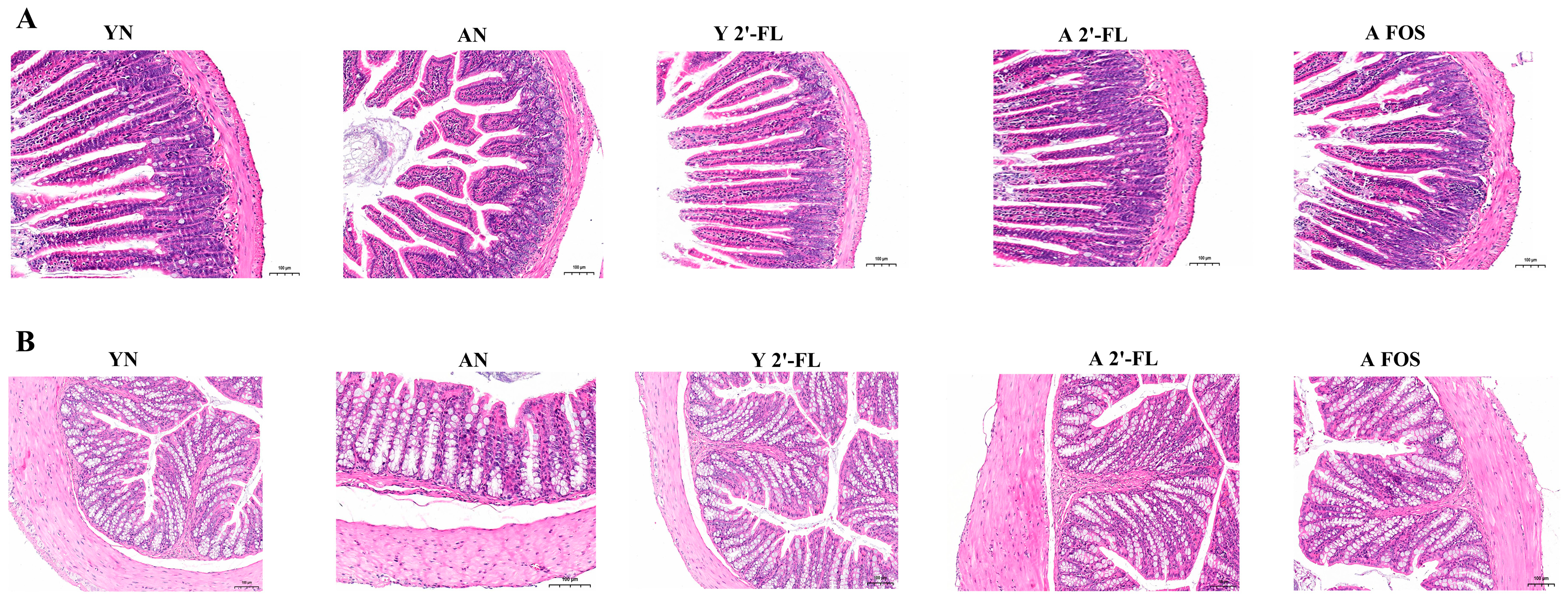

3.6. Tissue Pathological Analysis

3.7. Effects of 2′-FL on Gene Expression of Immune Aging and Oxidative Stress Factors in Mice of Each Group

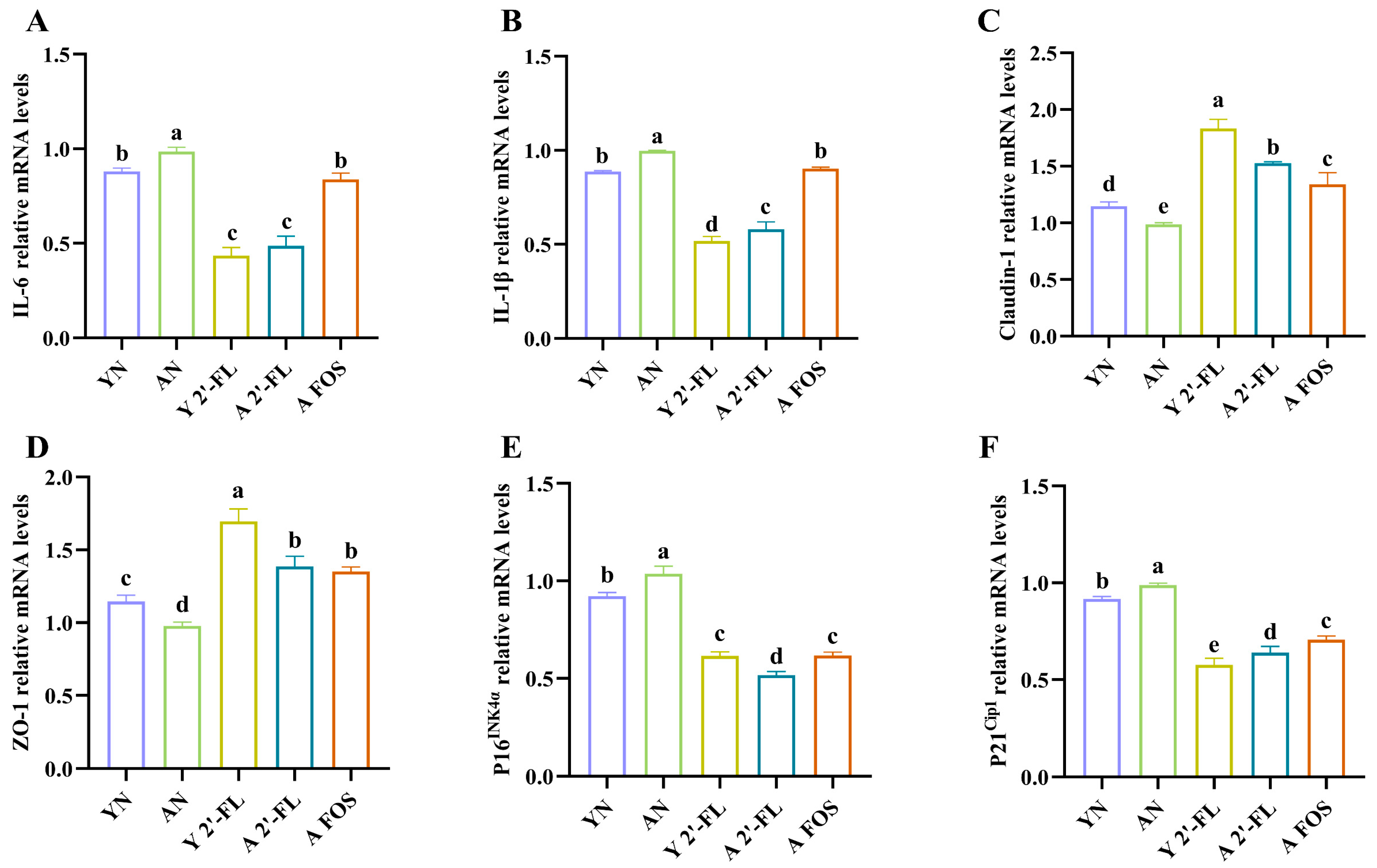

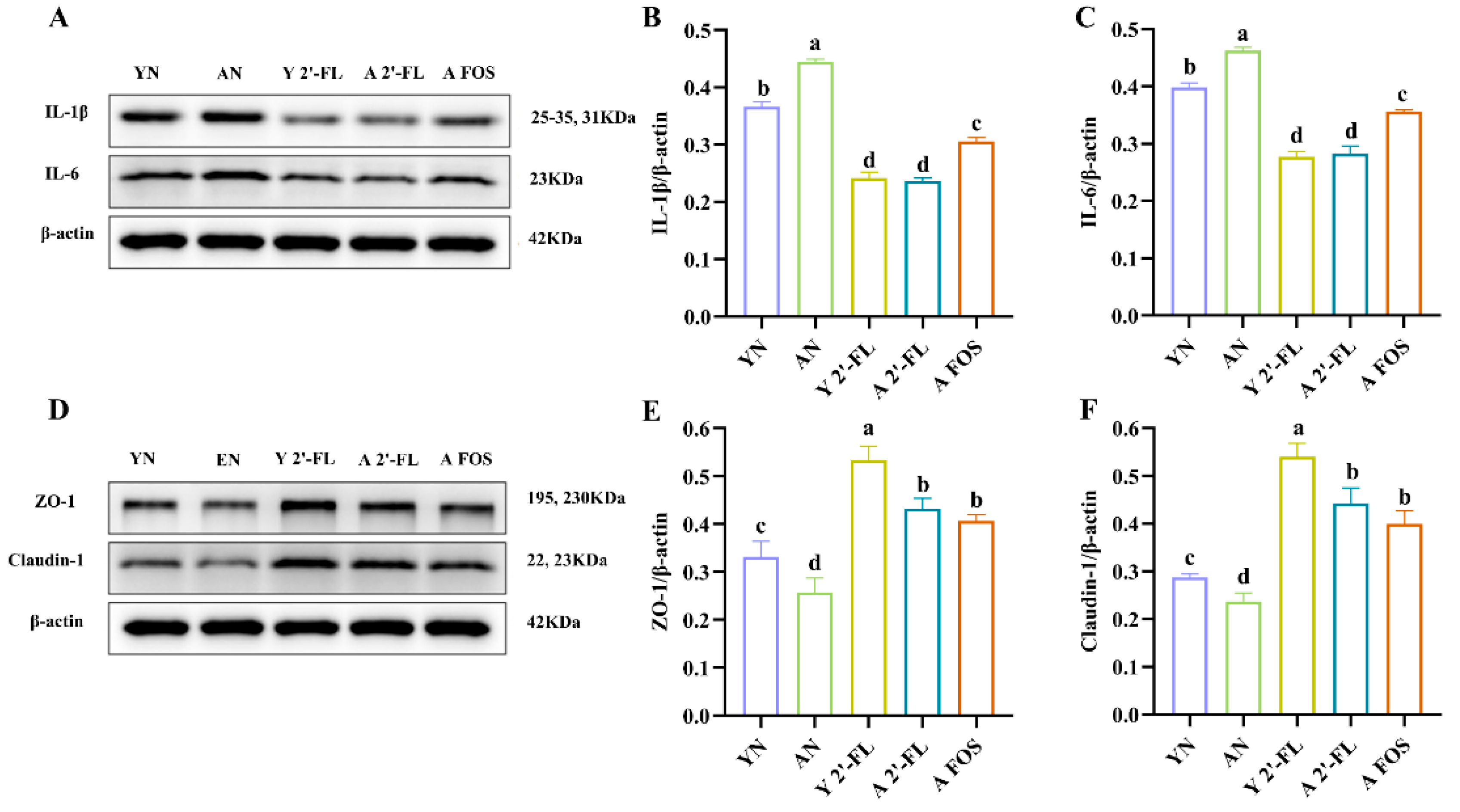

3.8. Effects of 2′-FL on the Expression of Intestinal-Related Inflammatory Factors and Tight Junction Proteins in Mice

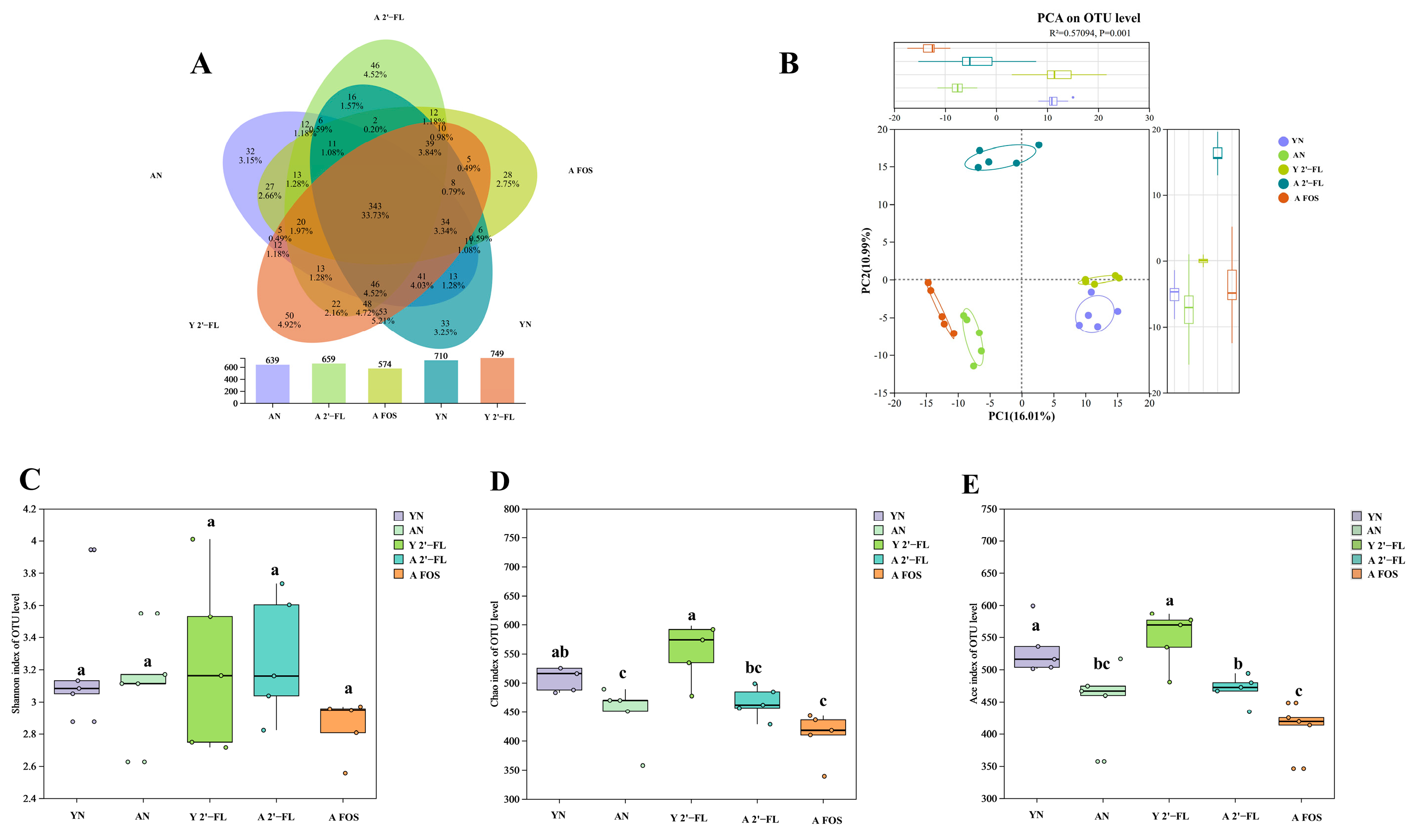

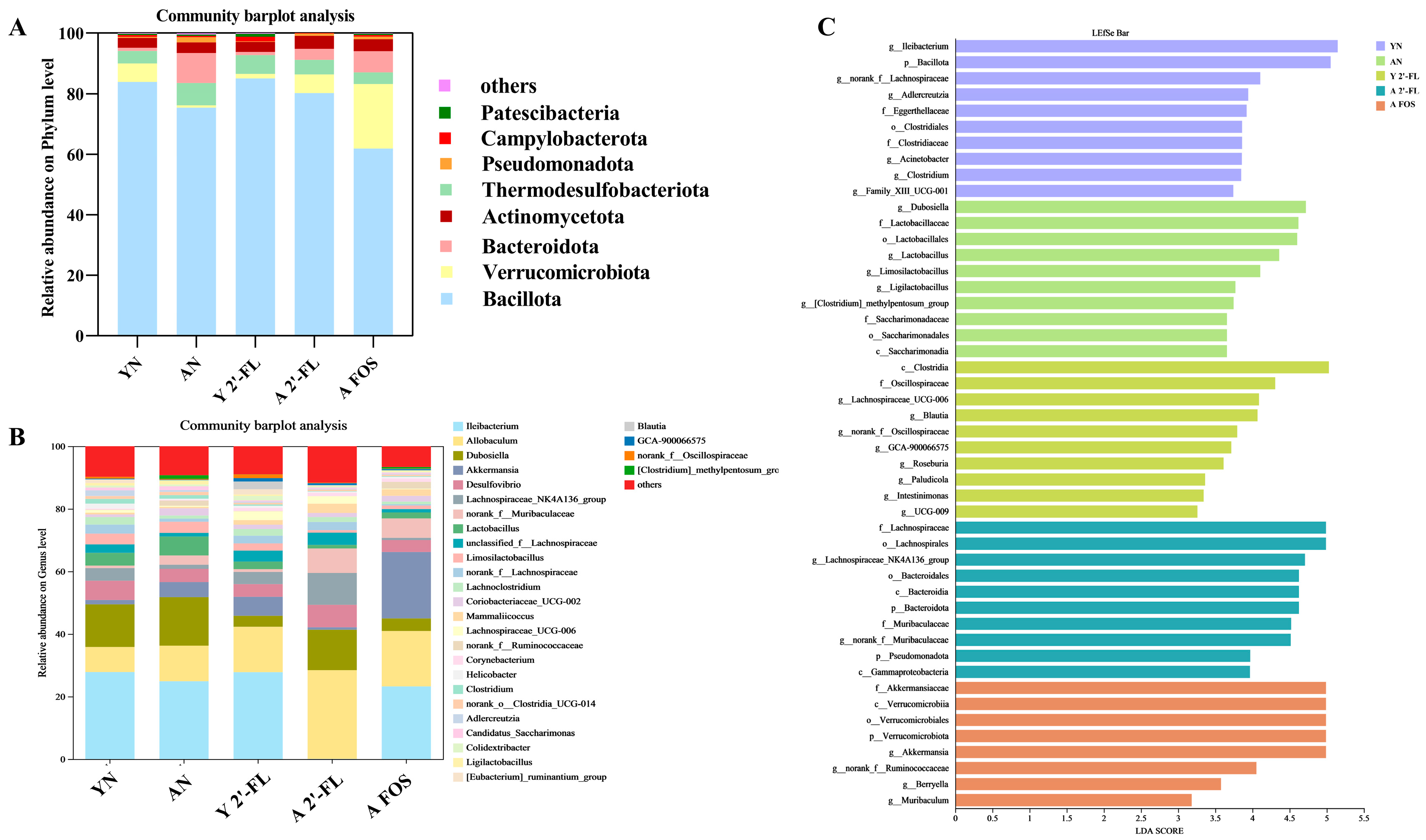

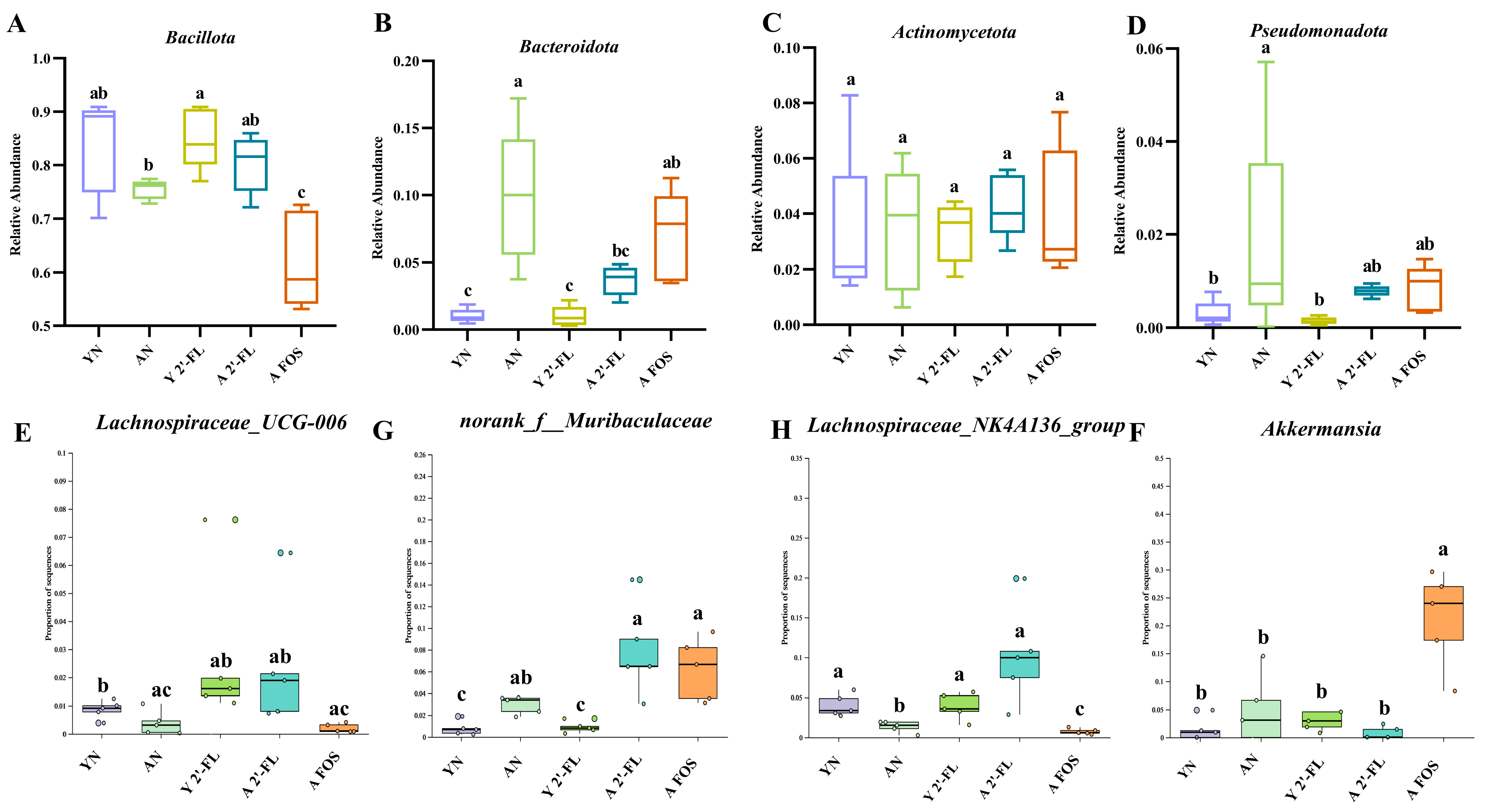

3.9. Effects of 2′-FL on the Gut Microbiota in Mice of Each Group

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ling, Z.; Liu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Yan, X.; Wu, S. Gut microbiota and aging. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2022, 62, 3509–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yin, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Wu, J. An investigation into the health status of the elderly population in China and the obstacles to achieving healthy aging. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, N.; Ghasemianrad, M.; Ammari-Allahyari, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M. Global prevalence of constipation in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2023, 135, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: A narrative review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrucci, L.; Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: Chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the healthy gut microbiota composition? A changing ecosystem across age, environment, diet, and diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, C.; Rudloff, S.; Baier, W.; Klein, N.; Strobel, S. Oligosaccharides in human milk: Structural, functional, and metabolic aspects. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2000, 20, 699–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas, Y.; Berger, B.; Carnielli, V.P.; Ksiazyk, J.; Lagström, H.; Sanchez Luna, M.; Migacheva, N.; Mosselmans, J.M.; Picaud, J.C.; Possner, M.; et al. Human milk oligosaccharides: 2′-fucosyllactose (2′-FL) and lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT) in infant formula. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salli, K.; Anglenius, H.; Hirvonen, J.; Hibberd, A.A.; Ahonen, I.; Saarinen, M.T.; Tiihonen, K.; Maukonen, J.; Ouwehand, A.C. The effect of 2′-fucosyllactose on simulated infant gut microbiome and metabolites; a pilot study in comparison to GOS and lactose. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkerman, R.; Faas, M.M.; de Vos, P. Non-digestible carbohydrates in infant formula as substitution for human milk oligosaccharide functions: Effects on microbiota and gut maturation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2019, 59, 1486–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, T.; Li, H.; Deng, Z.; Li, J.; Zheng, L.; Liao, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, B. Cognitive and behavioral benefits of 2′-fucosyllactose in growing mice: The roles of 5-hydroxytryptophan and gut microbiota. Microbiome 2025, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, F.; Zhao, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xie, J. Kaempferol Alleviates Murine Experimental Colitis by Restoring Gut Microbiota and Inhibiting the LPS-TLR4-NF-κB Axis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 679897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Jiang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, C.; Han, S.; Che, H. Cholera toxin induces food allergy through Th2 cell differentiation which is unaffected by Jagged2. Life Sci. 2020, 263, 118514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, K.; Tan, J.; Mao, Y. Alginate oligosaccharide alleviates aging-related intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction by blocking FGF1-mediated TLR4/NF-κB p65 pathway. Phytomedicine 2023, 116, 154806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katiraei, S.; Anvar, Y.; Hoving, L.; Berbée, J.F.; van Harmelen, V.; Willems van Dijk, K. Evaluation of full-length versus V4-region 16S rRNA sequencing for phylogenetic analysis of mouse intestinal microbiota after a dietary intervention. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.P.; Wang, J.; Zhou, S.X.; Huang, D.C.; Qi, G.H.; Chen, G.T. Ginger polysaccharides enhance intestinal immunity by modulating gut microbiota in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 223, 1308–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Di, Q.; Liang, T.; Zhou, N.; Chen, H.; Zeng, Z.; Luo, Y.; Shaker, M. Effects of in vitro simulated digestion and fecal fermentation of polysaccharides from straw mushroom (Volvariella volvacea) on its physicochemical properties and human gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 239, 124188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowiak-Kopeć, P.; Śliżewska, K. The effect of probiotics on the production of short-chain fatty acids by human intestinal microbiome. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Zang, H.; Tang, J.; Zhang, H.; Yu, J.; Jia, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, J. Lactobacillus gasseri ATCC33323 affects the intestinal mucosal barrier to ameliorate DSS-induced colitis through the NR1I3-mediated regulation of E-cadherin. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Pang, S.J.; Zhang, K.W.; Li, P.Y.; Li, P.G.; Yang, C. Dietary vitamin A modifies the gut microbiota and intestinal tissue transcriptome, impacting intestinal permeability and the release of inflammatory factors, thereby influencing Aβ pathology. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1367086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planer, J.D.; Peng, Y.; Kau, A.L.; Blanton, L.V.; Ndao, I.M.; Tarr, P.I.; Warner, B.B.; Gordon, J.I. Development of the gut microbiota and mucosal IgA responses in twins and gnotobiotic mice. Nature 2016, 534, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, E.; Gómez de Las Heras, M.M.; Gabandé-Rodríguez, E.; Desdín-Micó, G.; Aranda, J.F.; Mittelbrunn, M. The role of T cells in age-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kociszewska, D.; Vlajkovic, S. Age-related hearing loss: The link between inflammaging, immunosenescence, and gut dysbiosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shemtov, S.J.; Emani, R.; Bielska, O.; Covarrubias, A.J.; Verdin, E.; Andersen, J.K.; Winer, D.A. The intestinal immune system and gut barrier function in obesity and ageing. FEBS J. 2023, 290, 4163–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Medina, D.; Stockwell, R.; McFadden, S.; Quinn, K.; Peck, M.R.; Bartke, A.; Hascup, K.N.; Hascup, E.R. Sexual dimorphic responses of C57BL/6 mice to fisetin or dasatinib and quercetin cocktail oral treatment. BioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tang, D. The complex link and disease between the gut microbiome and the immune system in infants. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 924119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinleyici, M.; Barbieur, J.; Dinleyici, E.C.; Vandenplas, Y. Functional effects of human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs). Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2186115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Shi, H.; Qian, W.; Meng, L.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wen, Z.; Han, M.; Peng, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Immunomodulatory Effects of a Prebiotic Formula with 2′-Fucosyllactose and Galacto-and Fructo-Oligosaccharides on Cyclophosphamide (CTX)-Induced Immunosuppressed BALB/c Mice via the Gut–Immune Axis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.M.; Demis, D.; Perelman, D.; Onge, M.S.; Petlura, C.; Cunanan, K.; Mathi, K.; Maecker, H.T.; Chow, J.M.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; et al. A human milk oligosaccharide alters the microbiome, circulating hormones, and metabolites in a randomized controlled trial of older adults. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ji, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y. Probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum promotes intestinal barrier function by strengthening the epithelium and modulating gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yu, S.; Li, Y.; Yao, B.; Yang, X. Astragalus polysaccharides-induced gut microbiota play a predominant role in enhancing of intestinal barrier function of broiler chickens. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.B.; Huang, H.; Ning, Y.; Xiao, J. Probiotics in the new era of Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs): HMO utilization and beneficial effects of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis M-63 on infant health. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Zheng, M.; Liang, W.; Ouyang, L.; Wang, S. 2′-Fucosyllactose synbiotics with Bifidobacterium bifidum to improve intestinal transcriptional function and gut microbiota in constipated mice. Food Res. Int. 2025, 217, 116840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Liu, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, H.; Tao, Q.; Wang, H.; Yan, H. Impact of traditional Chinese medicine treatment on chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced depression-like behaviors: Intestinal microbiota and gut microbiome function. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 5886–5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, A.; Stewart, L.; Blanchard, J.; Leschine, S. Untangling the genetic basis of fibrolytic specialization by Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae in diverse gut communities. Diversity 2013, 5, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, C.J.; Beiko, R.G. A phylogenomic view of ecological specialization in the Lachnospiraceae, a family of digestive tract-associated bacteria. Genome Biol. Evol. 2014, 6, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Tian, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, W. Galacto-oligosaccharides improve barrier function and relieve colonic inflammation via modulating mucosa-associated microbiota composition in lipopolysaccharides-challenged piglets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, H.; Yu, R.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P.; Chen, W.; Yang, B. Human milk oligosaccharides 2′-fucosyllactose and 3-fucosyllactose attenuate ovalbumin-induced food allergy through immunoregulation and gut microbiota modulation. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 1267–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hu, J.Q.; Song, Y.J.; Yin, J.; Wang, Y.Y.F.; Peng, B.; Zhang, B.W.; Liu, J.M.; Dong, L.; Wang, S. 2′-Fucosyllactose ameliorates oxidative stress damage in d-Galactose-induced aging mice by regulating gut microbiota and AMPK/SIRT1/FOXO1 pathway. Foods 2022, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Yu, L.; Tian, F.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W.; Zhai, Q. 2′-Fucosyllactose alleviate immune checkpoint blockade-associated colitis by reshaping gut microbiota and activating AHR pathway. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 2543–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Kou, R.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Hu, Y.Z.; Wang, S. Wang, S. 2’-Fucosyllactose attenuates aging-related metabolic disorders through modulating gut microbiome-T cell axis. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e14343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, F.; Liu, B. Gut microbiota-derived short chain fatty acids act as mediators of the gut–brain axis targeting age-related neurodegenerative disorders: A narrative review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2025, 65, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Kauppinen, A.; Kaarniranta, K. Emerging role of NF-κB signaling in the induction of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Cell. Signal. 2012, 24, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.J.; Sturmoski, M.A.; May, R.; Sureban, S.M.; Dieckgraefe, B.K.; Anant, S.; Houchen, C.W. Loss of p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 enhances intestinal stem cell survival following radiation injury. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastr. L 2009, 296, G245–G254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Basu, N.; Saha, S.; Khan, I.; Ramachandra, S.G.; Visweswariah, S.S. Intestinal cell proliferation and senescence are regulated by receptor guanylyl cyclase C and p21. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pettan-Brewer, C.; Treuting, M.P. Practical pathology of aging mice. Pathobiol. Aging Age-Relat. Dis. 2011, 1, 7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, N.; Arboleya, S.; Fernández-Navarro, T.; de Los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Gonzalez, S.; Gueimonde, M. Age-associated changes in gut microbiota and dietary components related with the immune system in adulthood and old age: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgarbieri, V.C.; Pacheco, M.T.B. Healthy human aging: Intrinsic and environmental factors. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2017, 20, e2017007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Leusink-Muis, T.; Kettelarij, N.; Van Ark, I.; Blijenberg, B.; Hesen, N.A.; Stahl, B.; Overbeek, S.A.; Garssen, J.; Folkerts, G.; et al. Human milk oligosaccharide 2′-fucosyllactose improves innate and adaptive immunity in an influenza-specific murine vaccination model. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuurveld, M.; Diks, M.A.P.; Kiliaan, P.C.J.; Garssen, J.; Folkerts, G.; Van′t Land, B.; Willemsen, L.E.M. Butyrate interacts with the effects of 2’FL and 3FL to modulate in vitro ovalbumin-induced immune activation, and 2’ FL lowers mucosal mast cell activation in a preclinical model for hen′s egg allergy. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1305833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, M.; Li, X.; Ren, Y.; Zhu, W.; Yu, K. Effects of 2’-fucosyllactose on the composition and metabolic activity of intestinal microbiota from piglets after in vitro fermentation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 1553–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H.H.; Shin, C.S.; Yoon, J.W.; Jeon, S.M.; Song, Y.H.; Kim, K.Y.; Kim, K. 2′-Fucosyllactose and 3-fucosyllactose alleviates Interleukin-6-induced barrier dysfunction and dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis by improving intestinal barrier function and modulating the intestinal microbiome. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Gene Sequence (5′-3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| ZO-1 | M0098f | TCTGATGGTGCTCTGCCTAAT |

| M0098r | GTCGCAAACCCACACTATCTC | |

| Claudin-1 | M0011f | TTATCGGAACTGTGGTAGAAC |

| M0011r | CTCAGGGAAGATGGTAAGGTA | |

| IL-1β | M0565f | AACAACAGTGGTCAGGACATA |

| M0565r | GGGAAGGCATTAGAAACAG | |

| IL-6 | M0067bf | CGGAGAGGAGACTTCACAGAG |

| M0067br | ATTTCCACGATTTCCCAGAG | |

| P16INK4α | M1506bf | AAGAGCGGGGACATCAAG |

| M1506br | CCAGCGGAACACAAAGAG | |

| P21Cip1 | M1359f | GGTTCCTTGCCACTTCTTAC |

| M1359r | CTAACTGCCATCCCTGTTCTA | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, S.; Li, Y.; Luo, T.; Huang, Y.; Che, H.; Pang, J.; Meng, X. The Effect of 2′-Fucosyllactose on Gut Health in Aged Mice. Foods 2025, 14, 4184. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244184

Jiang S, Li Y, Luo T, Huang Y, Che H, Pang J, Meng X. The Effect of 2′-Fucosyllactose on Gut Health in Aged Mice. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4184. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244184

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Songsong, Yang Li, Tingting Luo, Yutong Huang, Huilian Che, Jinzhu Pang, and Xiangren Meng. 2025. "The Effect of 2′-Fucosyllactose on Gut Health in Aged Mice" Foods 14, no. 24: 4184. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244184

APA StyleJiang, S., Li, Y., Luo, T., Huang, Y., Che, H., Pang, J., & Meng, X. (2025). The Effect of 2′-Fucosyllactose on Gut Health in Aged Mice. Foods, 14(24), 4184. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244184