Exploring the Role of Tamarind Seed Polysaccharides in Modulating the Structural, Digestive, and Emulsion Stability Properties of Waxy Corn Starch Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of WMS-TSP Complexes

2.3. Fabrication of Emulsions Stabilized by WMS-TSP Complexes

2.4. Characteristics of WMS-TSP Complexes

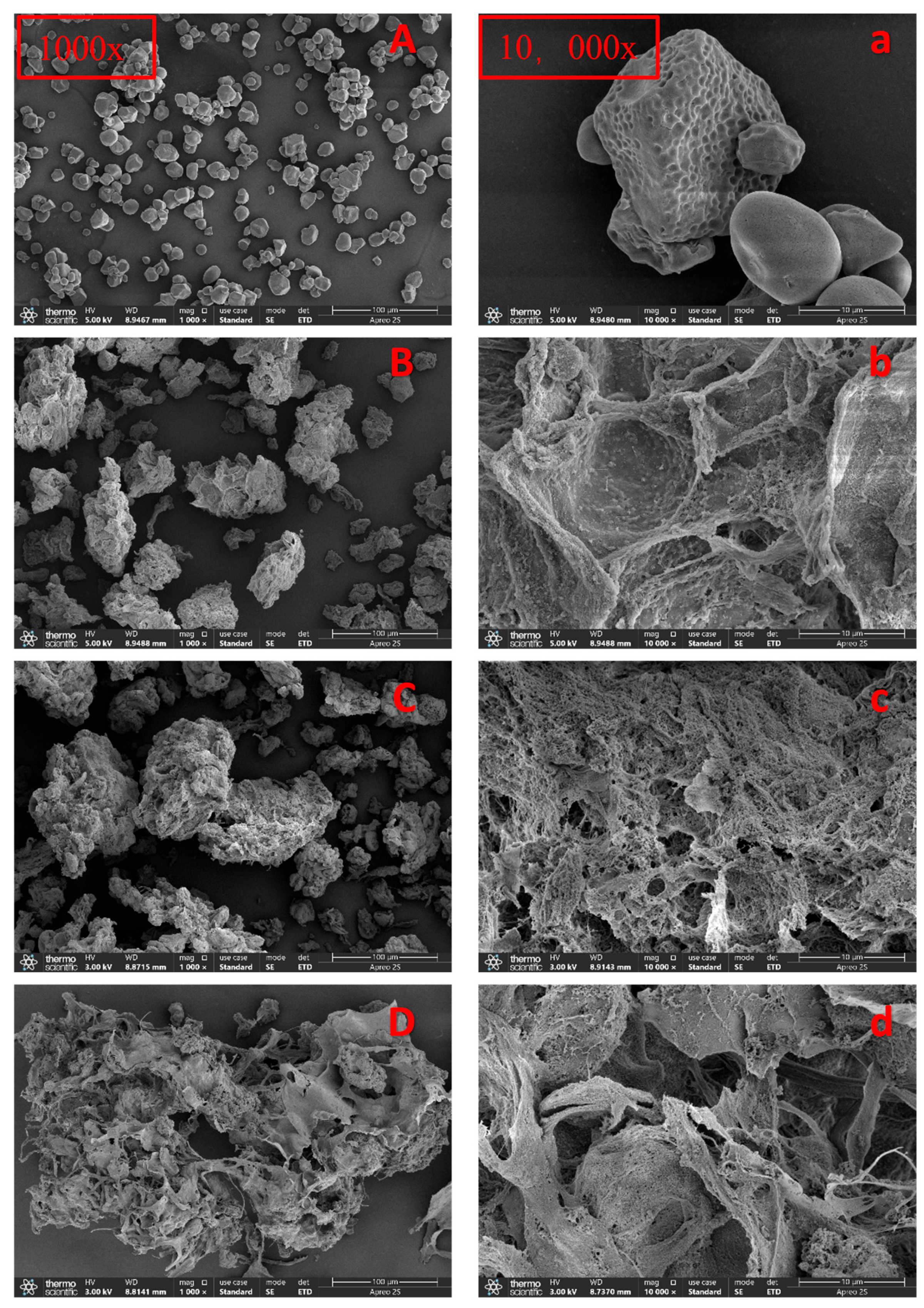

2.4.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

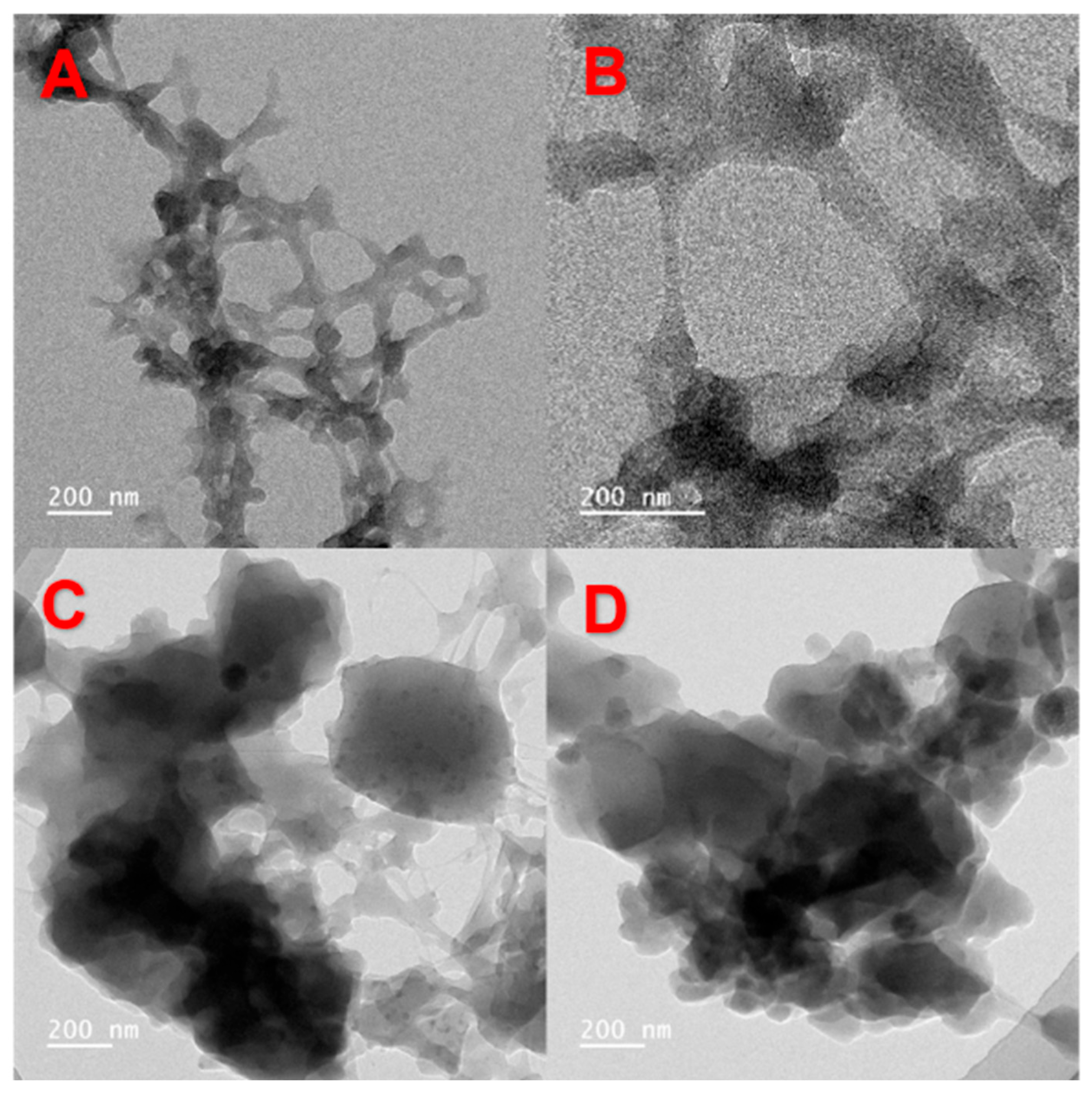

2.4.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

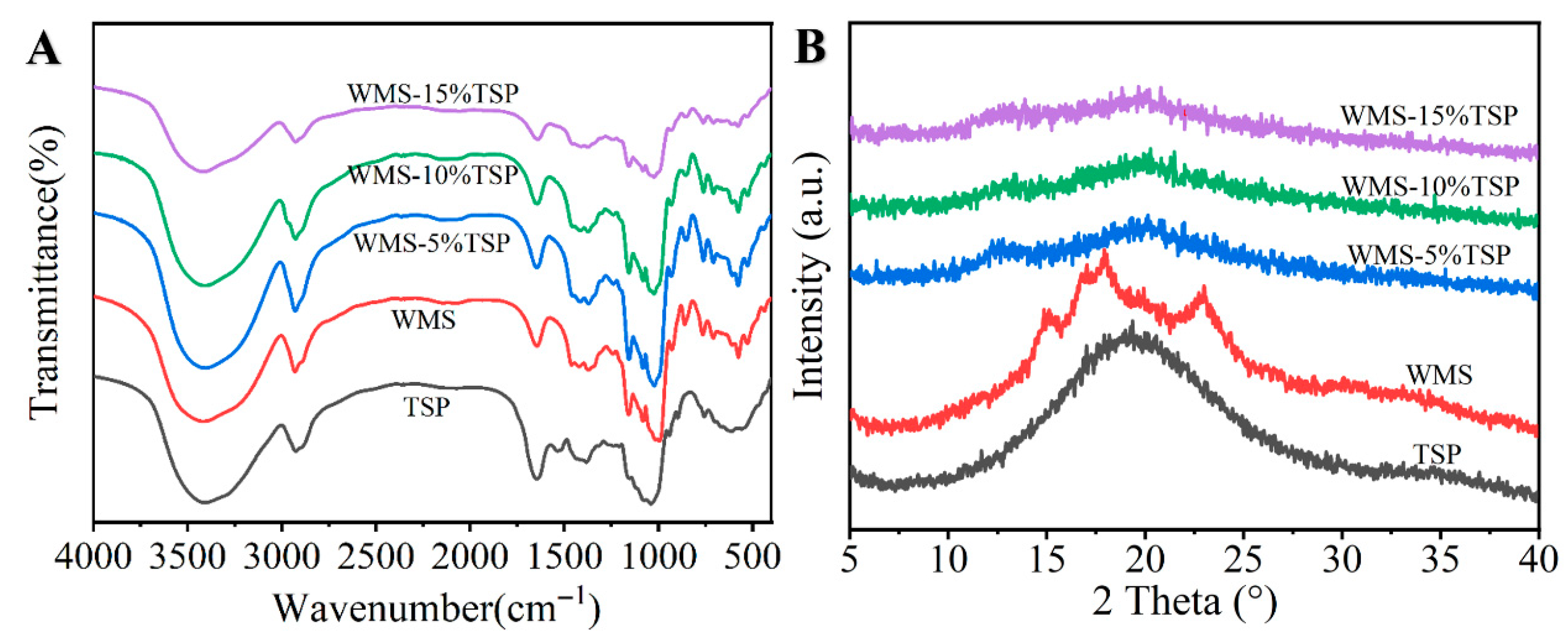

2.4.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Analysis

2.4.4. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.4.5. Particle Size Measurement

2.4.6. Three-Phase Contact Angle Measurement

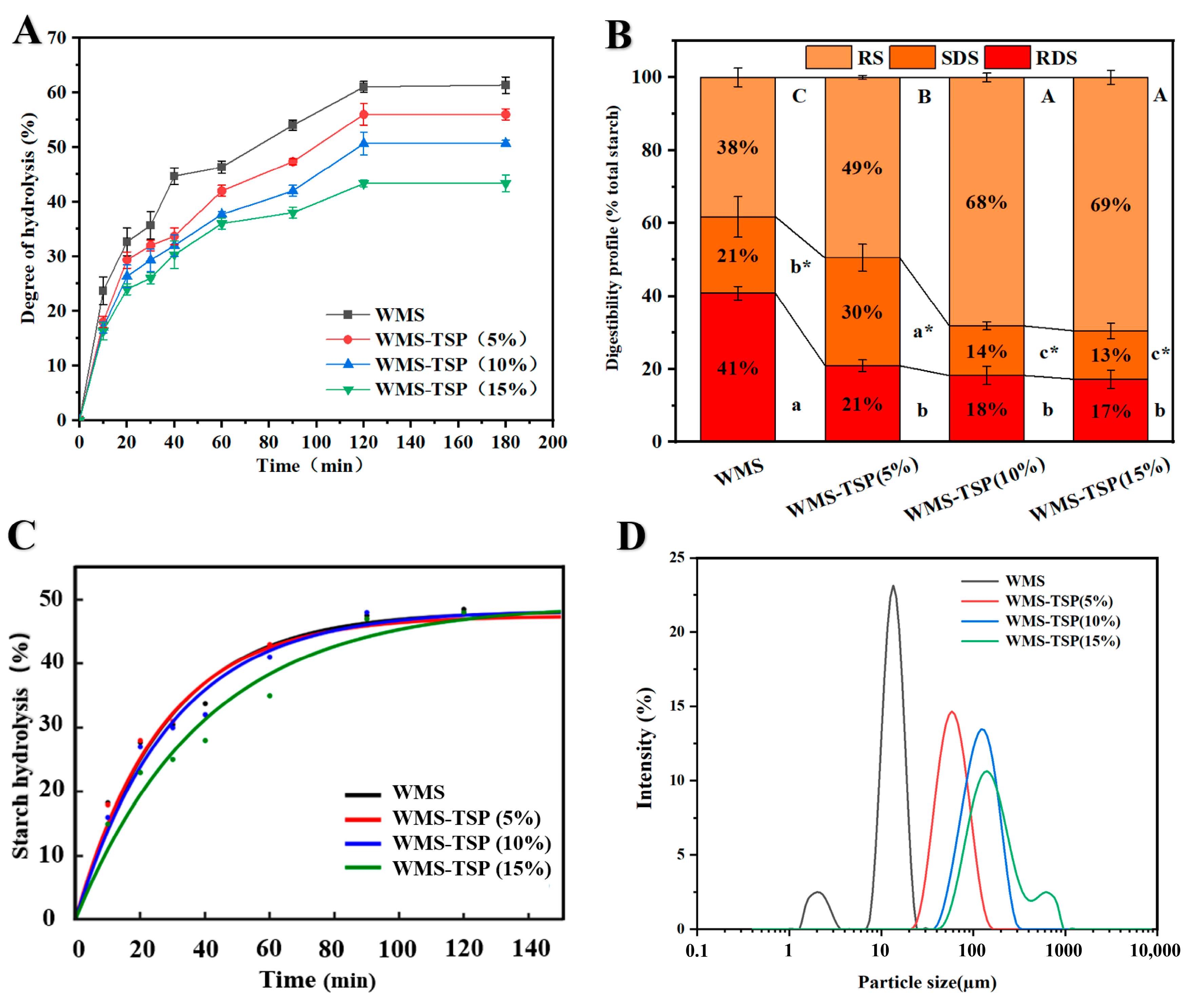

2.4.7. In Vitro Digestibility

2.4.8. Kinetic Modeling of In Vitro Starch Digestion

2.5. Characteristics of WMS-TSP Complexes Emulsions

2.5.1. Storage Stability

2.5.2. Microstructure Observation

2.5.3. Measuring Rheology

2.5.4. Droplet Size and Zeta Potential of Emulsion

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of WMS-TSP Complexes

3.1.1. SEM Analysis

3.1.2. FT-IR Analysis

3.1.3. XRD Analysis

3.1.4. TEM Analysis

3.1.5. Particle Size

3.1.6. In Vitro Digestibility Analysis

3.1.7. Kinetic Analysis of In Vitro Starch Digestion

3.1.8. Three-Phase Contact Angle

3.2. Characteristics of Emulsions Stabilized by WMS-TSP Complexes

3.2.1. Physical Stability

3.2.2. Rheological Analysis

3.2.3. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matos, M.; Marefati, A.; Barrero, P.; Rayner, M.; Gutiérrez, G. Resveratrol loaded Pickering emulsions stabilized by OSA modified rice starch granules. Food Res. Int. 2021, 139, 109837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandri, M.; Kachrimanidou, V.; Papapostolou, H.; Papadaki, A.; Kopsahelis, N. Sustainable Food Systems: The Case of Functional Compounds Towards the Development of Clean Label Food Products. Foods 2022, 11, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Zhou, H.; Bai, L.; Rojas, O.J.; McClements, D.J. Development of food-grade Pickering emulsions stabilized by a mixture of cellulose nanofibrils and nanochitin. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 113, 106451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkawy, A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Rodrigues, A.E. Chitosan-based Pickering emulsions and their applications: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 250, 116885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.D.; Hong, J.S.; Pyo, S.M.; Ko, E.; Shin, H.Y.; Kim, J.Y. Starch nanoparticles produced via acidic dry heat treatment as a stabilizer for a Pickering emulsion: Influence of the physical properties of particles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 239, 116241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Lin, R.; Liang, Y.; Jiao, S.; Zhong, L. Characterization of acetylated starch nanoparticles for potential use as an emulsion stabilizer. Food Chem. 2023, 400, 133873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Chen, L.; Guo, X.; Liang, Y.; Xie, F. Understanding the multi-scale structure and digestibility of different waxy maize starches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 144, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Qin, L.; Chen, T.; Yu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, W.; Xie, J.; Ji, X. Modification of starch by polysaccharides in pasting, rheology, texture and in vitro digestion: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 207, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Du, Q.; Miao, T.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Jia, D. Interaction between potato starch and Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 127, 107509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Jia, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, Q.; Barba, F.J.; Wan, L.; Fu, Y.; Wang, X. Effects of Laminaria japonica polysaccharides on gelatinization properties and long-term retrogradation of wheat starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 133, 107908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Yu, M.; Yin, H.; Peng, L.; Cao, Y.; Wang, S. Multiscale structures, physicochemical properties, and in vitro digestibility of oat starch complexes co-gelatinized with jicama non-starch polysaccharides. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 144, 108983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, H.; Bhatti, H.N.; Bhatti, I.A. Replacement of sodium alginate polymer, urea and sodium bicarbonate in the conventional reactive printing of cellulosic cotton. J. Polym. Eng. 2019, 39, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Li, X.; Sun, X.; Kou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, H.; et al. Molecular aggregation via partial Gal removal affects physicochemical and macromolecular properties of tamarind kernel polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 285, 119264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, F.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, Z.; Wu, Y.; Ai, L. Effects and mechanism of sucrose on retrogradation, freeze-thaw stability, and texture of corn starch-tamarind seed polysaccharide complexes. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, T.; MacCalman, T.; Dinu, V.; Phillips-Jones, M.K.; Harding, S.E.; Ottino, S. Hydrodynamic Compatibility of Hyaluronic Acid and Tamarind Seed Polysaccharide as Ocular Mucin Supplements. Polymers 2020, 12, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, W.; Guo, C.; Hu, X.; Yi, J. Role of pectin characteristics in orange juice stabilization: Effect of high-pressure processing in combination with centrifugation pretreatments. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 215, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englyst, H.N.; Kingman, S.M.; Cummings, J.H. Classification and measurement of nutritionally important starch fractions. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1992, 46 (Suppl. S2), S33–S50. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z.; Wu, M.; Liao, Q.; Zhu, N.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wu, J. Hot-water soluble fraction of starch as particle-stabilizers of oil-in-water emulsions: Effect of dry heat modification. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 336, 122130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Li, T.; Zhou, L.; Chen, L.; Lyu, Q.; Liu, G.; Chen, X.; Wang, X. Potato starch/naringenin complexes for high-stability Pickering emulsions: Structure, properties, and emulsion stabilization mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264 Pt 2, 130597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, L.; McClements, D.J.; Zou, Y.; Chen, G.; Jin, Z. Vanillin-assisted preparation of chitosan-betaine stabilized corn starch gel: Gel properties and microstructure characteristics. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 148, 109510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, S.; Luo, Y.; Xie, J.; Shen, M. Effects of Mesona chinensis Benth polysaccharide on physicochemical and rheological properties of sweet potato starch and its interactions. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 99, 105371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Jia, Z.; Hou, L.; Xiao, S.; Yang, H.; Ding, W.; Wang, X.; Wei, Y.; Wu, Y. Study on physicochemical properties and anti-aging mechanism of wheat starch by anionic polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253 Pt 8, 127431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Tian, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiao, A.; Jin, Z. Effect of frying on the pasting and rheological properties of normal maize starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 77, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Xie, H.; Hu, H.; Ouyang, K.; Li, G.; Zhong, J.; Zhao, Q.; Hu, X.; Xiong, H. V-type granular starches prepared by maize starches with different amylose contents: An investigation in structure, physicochemical properties and digestibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266 Pt 2, 131092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Rao, L.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X. Effect of high pressure homogenization on the interaction between corn starch and cyanidin-3-O-glucoside. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253 Pt 2, 126758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Hu, Y.; Jin, Z.; McClements, D.J.; Qin, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, J. A review of green techniques for the synthesis of size-controlled starch-based nanoparticles and their applications as nanodelivery systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 92, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Yang, J.; Hua, S.; Hong, Y.; Gu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Li, C.; Li, Z. Characteristics of starch-based Pickering emulsions from the interface perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Hong, J.S.; Choi, S.J.; Moon, T.W. Modeling of in vitro digestion behavior of corn starches of different digestibility using modified log of slope (LOS) method. Food Res. Int. 2020, 146, 110436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Ou, Y.; Lan, X.; Tang, J.; Zheng, B. Effects of laminarin on the structural properties and in vitro digestion of wheat starch and its application in noodles. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 178, 114543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, C.; Zhu, S.; Zhong, F.; Huang, D.; Li, Y. Understanding the mechanisms of whey protein isolate mitigating the digestibility of corn starch by in vitro simulated digestion. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tian, Y.; Sun, B.; Cai, C.; Ma, R.; Jin, Z. Measurement and characterization of external oil in the fried waxy maize starch granules using ATR-FTIR and XRD. Food Chem. 2018, 242, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzoumaki, M.V.; Moschakis, T.; Biliaderis, C.G. Effect of soluble polysaccharides addition on rheological properties and microstructure of chitin nanocrystal aqueous dispersions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 95, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, S.; Liu, X.; Ma, H.; Liu, B.; Liang, G. Multi-scale stabilization mechanism of pickering emulsion gels based on dihydromyricetin/high-amylose corn starch composite particles. Food Chem. 2021, 355, 129660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Gong, H.; Zhu, W.; Wang, J.; Zhai, Y.; Lin, S. Pickering emulsion stabilized by composite-modified waxy corn starch particles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 205, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J.; Xia, Y.; Song, Z.; Ai, L. An amendment to the fine structure of galactoxyloglucan from Tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) seed. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | R1047/1022 | R1022/955 | Relative Crystallinity (%) | D10 (μm) | D50 (μm) | D90 (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WMS | 0.895 ± 0.006 a | 1.24 ± 0.0091 d | 26.90 ± 0.02 a | 4.85 ± 1.40 a | 8.72 ± 0.11 a | 11.70 ± 1.62 a |

| WMS-TSP (5%) | 0.905 ± 0.002 b | 0.95 ± 0.0033 c | 3.21 ± 0.09 b | 68.06 ± 2.18 b | 105.71 ± 0.61 b | 164.18 ± 0.31 b |

| WMS-TSP (10%) | 0.917 ± 0.012 c | 0.83 ± 0.0032 b | 4.57 ± 0.19 c | 91.28 ± 1.53 c | 164.18 ± 0.15 c | 255.00 ± 0.05 c |

| WMS-TSP (15%) | 0.928 ± 0.001 d | 0.55 ± 0.0031 a | 4.54 ± 0.13 c | 141.77 ± 2.91 d | 295.31 ± 0.42 d | 824.99 ± 1.31 d |

| Sample | C∞ (%) | k (min−1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| WMS | 49.82 ± 0.94 | 0.0523 ± 0.0019 a | 0.979 |

| WMS-TSP 5% | 47.28 ± 0.14 | 0.0403 ± 0.0023 b | 0.979 |

| WMS-TSP 10% | 47.99 ± 0.73 | 0.0338 ± 0.0035 b | 0.977 |

| WMS-TSP 15% | 48.73 ± 1.19 | 0.0280 ± 0.0029 b | 0.971 |

| Sample | Emulsifying Index (EI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 30 | Day 60 | Day 90 | |

| WMS | - | - | - | - |

| WMS-TSP (0.5%) | 84.7 ± 1.8 c | 75.3 ± 3.1 c | 74.0 ± 3.5 b | 70.7 ± 2.3 c |

| WMS-TSP (1.0%) | 88.7 ± 3.1 bc | 78.0 ± 5.3 bc | 75.3 ± 5.0 b | 74.7 ± 4.2 bc |

| WMS-TSP (1.5%) | 93.3 ± 2.3 a | 90.7 ± 1.2 a | 90.3 ± 1.1 a | 89.3 ± 1.2 a |

| WMS-TSP (2.0%) | 91.3 ± 1.7 a | 82.7 ± 1.0 b | 80.3 ± 2.1 b | 77.3 ± 1.9 b |

| Sample | Droplet Size Distribution (μm) | Zeta Potential (mV) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D10 | D50 | D90 | Dav | ||

| WMS | - | - | - | - | - |

| WMS-TSP (0.5%) | 110.06 ± 1.40 a | 133.38 ± 0.19 a | 176.89 ± 1.31 a | 136.47 ± 0.47 a | −39.63 ± 2.66 c |

| WMS-TSP (1.0%) | 117.43 ± 0.18 a | 152.17 ± 0.32 b | 186.97 ± 0.47 b | 154.14 ± 0.68 b | −47.96 ± 1.48 b |

| WMS-TSP (1.5%) | 131.87 ± 1.13 b | 174.31 ± 0.61 c | 201.84 ± 0.73 c | 179.66 ± 0.39 c | −52.01 ± 0.37 a |

| WMS-TSP (2.0%) | 127.15 ± 0.78 c | 169.29 ± 0.41 c | 198.67 ± 0.89 c | 175.94 ± 1.05 c | −56.41 ± 1.14 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ya, X.; Ma, Y.; Song, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, C.; Yi, J. Exploring the Role of Tamarind Seed Polysaccharides in Modulating the Structural, Digestive, and Emulsion Stability Properties of Waxy Corn Starch Composites. Foods 2025, 14, 4152. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234152

Ya X, Ma Y, Song Z, Jiang Y, Guo C, Yi J. Exploring the Role of Tamarind Seed Polysaccharides in Modulating the Structural, Digestive, and Emulsion Stability Properties of Waxy Corn Starch Composites. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4152. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234152

Chicago/Turabian StyleYa, Xiangyu, Yongshuai Ma, Zibo Song, Yongli Jiang, Chaofan Guo, and Junjie Yi. 2025. "Exploring the Role of Tamarind Seed Polysaccharides in Modulating the Structural, Digestive, and Emulsion Stability Properties of Waxy Corn Starch Composites" Foods 14, no. 23: 4152. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234152

APA StyleYa, X., Ma, Y., Song, Z., Jiang, Y., Guo, C., & Yi, J. (2025). Exploring the Role of Tamarind Seed Polysaccharides in Modulating the Structural, Digestive, and Emulsion Stability Properties of Waxy Corn Starch Composites. Foods, 14(23), 4152. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234152