Preparation and Quality Evaluation of Steamed Buns with Spirulina Powder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Dough and Steamed-Bun-Making Procedure

2.3. Observation on Microstructure of Dough

2.4. Basic Quality Characteristics of SP Steamed Buns

2.4.1. Specific Volume

2.4.2. Height to Diameter Ratio

2.4.3. Color Analysis

2.4.4. Textural Properties

2.5. Sensory Analysis

2.6. Antioxidant Activity of SP Steamed Buns

2.6.1. Preparation of Extract

2.6.2. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Ability

2.7. Total Phenolic Content of SP Steamed Buns

2.8. Determination of Protein Content

2.9. Total Free Amino Acids (TFAAs) Content of SP Steamed Buns

2.10. Statistics Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Influence of SP Addition on the Microstructure of Dough

3.2. The Effects of SP Addition on Basic Quality Characters of Steamed Buns

3.2.1. Specific Volume and Height-to-Diameter Ratio of SP Steamed Buns

3.2.2. Color Change of SP Steamed Buns

3.2.3. Textural Properties of SP Steamed Buns

3.3. Overall Sensory Quality of SP Steamed Buns

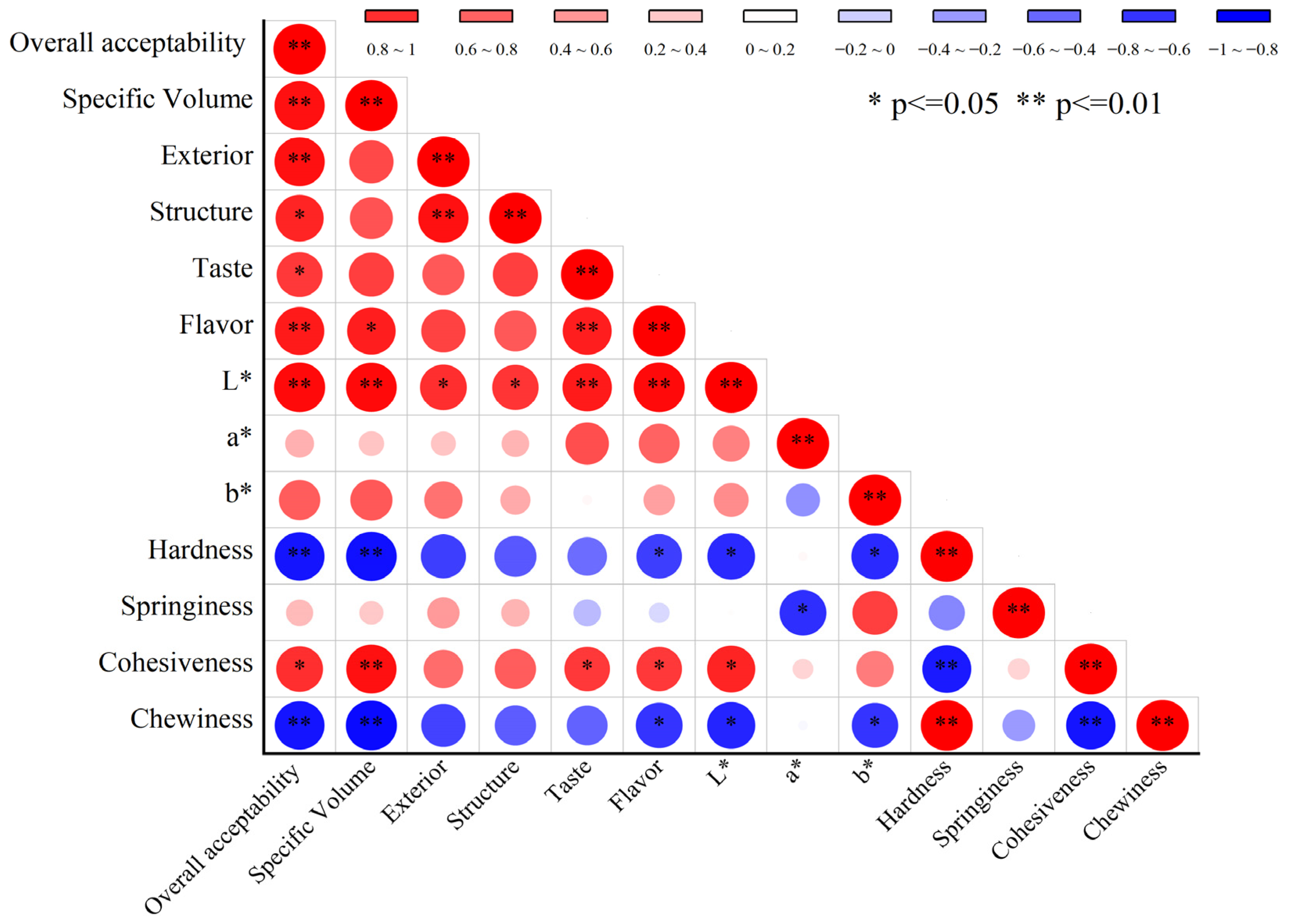

3.4. Correlation Analysis Between the Quality Characteristics of SP Steamed Buns

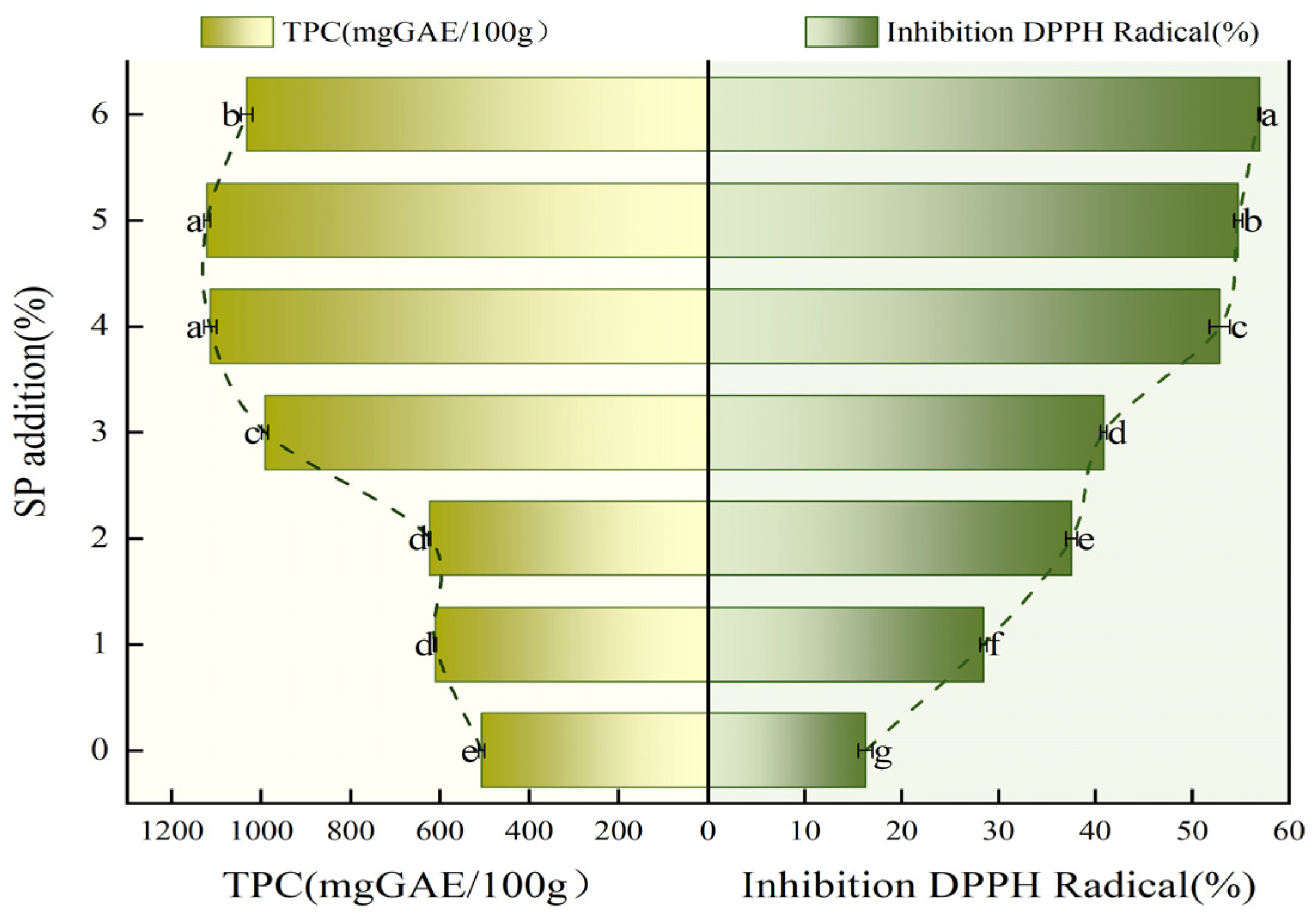

3.5. The Antioxidant Capacity of SP Steamed Buns

3.6. The Protein Content and Composition of Free Amino Acids in SP Steamed Buns

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kulshreshtha, A.; Zacharia, A.J.; Jarouliya, U.; Bhadauriya, P.; Prasad, G.B.; Bisen, P.S. Spirulina in health care management. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2008, 9, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, V.V.; Benemann, J.; Vonshak, A.; Belay, A.; Ras, M.; Unamunzaga, C.; Cadoret, J.-P.; Rizzo, A. Spirulina in the 21st century: Five reasons for success in Europe. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025, 37, 2203–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkot, W.F.; Elmahdy, A.; El-Sawah, T.H.; Alghamdia, O.A.; Alhag, S.K.; Al-Shahari, E.A.; Al-Farga, A.; Ismail, H.A. Development and characterization of a novel flavored functional fermented whey-based sports beverage fortified with Spirulina platensis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 258, 128999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.D.P.; Burck, M.; Costa, S.F.F.d.; Assis, M.; Braga, A.R.C. Spirulina as a Key Ingredient in the Evolution of Eco-Friendly Cosmetics. BioTech 2025, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fais, G.; Manca, A.; Bolognesi, F.; Borselli, M.; Concas, A.; Busutti, M.; Broggi, G.; Sanna, P.; Castillo-Aleman, Y.M.; Rivero-Jiménez, R.A.; et al. Wide Range Applications of Spirulina: From Earth to Space Missions. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrenti, V.; Castagna, D.A.; Fortinguerra, S.; Buriani, A.; Scapagnini, G.; Willcox, D.C. Spirulina Microalgae and Brain Health: A Scoping Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, S.; Chaudhary, K.; Aziz, H.; Amin, S.; Sipra, H.M.; Ansar, S.; Rasheed, H.; Naeem, M.; Onyeaka, H. Trends in extracting protein from microalgae Spirulina platensis, using innovative extraction techniques: Mechanisms, potentials, and limitations. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 65, 4293–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Li, J.; Zhong, H.; Xie, J.; Zhang, P.; Lu, Q.; Li, J.; Xu, P.; Chen, P.; Leng, L.; et al. Anti-oxidation properties and therapeutic potentials of spirulina. Algal Res. 2021, 55, 102240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, T.; Mayre, E.; Echeverria, G.; Viñas, I.; Villaró, S.; Acién-Fernández, F.G.; Castellari, M.; Aguiló-Aguayo, I. Potential of the microalgae Nannochloropsis and Tetraselmis for being used as innovative ingredients in baked goods. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 115, 108439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade Bordulis, C.B.; Moraes, L.; Vieira Costa, J.A.; Greque de Morais, M. Development of functional shakes for the Elderly: Utilization of Spirulina biomass and açaí fruit components. Food Biosci. 2025, 71, 107117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, R.; Aksay, S. Investigation of sensorial and physicochemical properties of yoghurt colored with phycocyanin of Spirulina platensis. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 46, e15941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman Seth, S.P. Preparation and Evaluation of Value Added Functional Whey Based Dairy Drink Using Spirulina Powder. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2021, 10, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouk, A.-H.A.; Yaseen, A.A.; Fouda, K.; Marrez, D.A.; Shedeed, N.A.; Mohammad, A.A. Hepatoprotective effect of functional biscuits enriched with spirulina. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 5059–5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taiti, C.; Stefano, G.; Percaccio, E.; Di Giacomo, S.; Iannone, M.; Marianelli, A.; Di Sotto, A.; Garzoli, S. Addition of Spirulina to Craft Beer: Evaluation of the Effects on Volatile Flavor Profile and Cytoprotective Properties. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beisler, N.; Sandmann, M. Integration of Arthrospira platensis (spirulina) into the brewing process to develop new beers with unique sensory properties. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 918772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitutskaya, O.I.; Donchenko, L.V.; Lukyanenko, M.V.; Limareva, N.S. Functional food compositions using spirulina for the production of health jelly. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 460, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira da Silva, E.; Rafaela da Silva Monteiro Wanderley, B.; Duarte de Lima, N.; Bettim Bianchini, C.; Beddin Fritzen-Freire, C.; Dias de Mello Castanho Amboni, R.; Verruck, S.; Larroza Nunes, I. Vegan salad dressing based on cashew nuts with or without Spirulina platensis: Physicochemical, rheological, and sensory characterization and in vitro digestion of phenolic compounds. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2025, 41, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Paternina, L.P.; Moraes, L.; Duarte Santos, T.; de Morais, M.G.; Costa, J.A.V. Spirulina and açai as innovative ingredients in the development of gummy candies. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e17261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, H.-H.; Tran, K.-D.; Le-Thi, L.; Nguyen-Thi, N.-N.; Nguyen-Van, T.; Dinh-Thi, T.-V.; Pham, T.-A.; Nguyen-Thi, T.; Vu-Thi, T. The Effect of the Addition of Spirulina spp. on the Quality Properties, Health Benefits, and Sensory Evaluation of Green Tea Kombucha. Food Biophys. 2024, 19, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimy, M.F.; Febrisiantosa, A.; Rakhmi Sefrienda, A.; Setiyawan, A.I.; Pratiwi, D.; Khasanah, Y.; Jasmadi, N.; Wahyuningsih, R.; Suwito, W.; Kurniawan, T.; et al. The impact of adding different levels of spirulina on the characteristics of halloumi cheese. Food Sci. 2024, 38, 101050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.A.; El-Sawah, T.H.; Ayyash, M.; Adhikari, B.; Elkot, W.F. Functionalization of Ricotta cheese with powder of spirulina platensis: Physicochemical, sensory, and microbiological properties. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 1968–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalver, R.; Nieto, G. Developing a functional gluten-free sourdough bread by incorporating quinoa, amaranth, rice and spirulina. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 201, 116162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejatian, M.; Ghandehari Yazdi, A.P.; Saberian, H.; Bazsefidpar, N.; Karimi, A.; Soltani, A.; Assadpour, E.; Toker, O.S.; Jafari, S.M. Application of Spirulina as an innovative ingredient in pasta and bakery products. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalver, R.; Martínez-Zamora, L.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Ros, G.; Nieto Martínez, G. Effect of hydroxytyrosol, Moringa, and spirulina on the physicochemical properties and nutritional characteristics of gluten-free brownies. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 12, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y. Effect of potato pulp on the staling and nutritional properties of wheat steamed bread. Cereal Chem. 2023, 100, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.-F.; Fang, W.; Fu, T.; Obireddy, S.R. Seeds of Coix lacryma-jobi as a functional additive in steamed buns: Effects on bun quality and starch digestibility. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 223, 117721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamat, H.; Ling, Y.Y.; Abdul Aziz, A.H.; Wahab, N.A.; Mohd Rosli, R.G.; Sarjadi, M.S.; Zainol, M.K.; Putra, N.R.; Yunus, M.A.C. Utilization of seaweed composite flour (Kappaphycus alvarezii) in the development of steamed bun. J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 1911–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.-J.; Chen, N.; Yu, Z.-L.; Sun, Q.; He, Q.; Zeng, W.-C. Effect of tea polyphenols on the quality of Chinese steamed bun and the action mechanism. J. Appl. Phycol. 2022, 87, 1500–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Deng, J.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, H.; Chen, Z. Preparation and quality evaluation of potato steamed bread with wheat gluten. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 3989–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Guo, S.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Ma, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, H. Effects of Siraitia grosvenorii seed flour on the properties and quality of steamed bread. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1249639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimah, S.; Sonjaya, M.F.; Andoyo, R.; Satya, A.; Nurhasanah, S.; Chrismadha, T. Physical and organoleptic characteristic of bread substituted with Spirulina platensis. In Biomass Conversion and Sustainable Biorefinery: Towards Circular Bioeconomy; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 295–306. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Shahid, A.; Su, K.; Zhao, A.; Zhang, B.; Xu, J. Comprehensive analysis of the effects of fresh Spirulina microcapsules on protein cross-linking and structural changes in wheat noodles. Food Chem. 2025, 482, 144034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cereals & Grains Association. Approved Methods of Analysis, 11th ed.; AACC Method 54-10.02; Cereals & Grains Association: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Lü, Y.G.; Li, X.Q.; Chen, J. Effect of Spirulina powder on rheological properties and gluten structure of dough. Food Sci. 2023, 44, 63–71, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 21118-2007; General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China. Steamed Bread Made of Wheat Flour. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- GB/T 17320-2013; General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China. Quality Classification of Wheat Varieties. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Shao, T.; Ma, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Wu, R.; Wang, X.-B.; Gu, R.-X.; Chen, X. Physical and nutritional properties of Chinese Steamed Bun (mantou) made with fermented soy milk. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 183, 184849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cankurtaran-Kömürcü, T.; Bilgiçli, N. Improvement of nutritional properties of regular and gluten-free cakes with composite flour. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2023, 31, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB5009.124-2016; National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China, National Medical Products Administra-tion. National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Amino Acids in Foods. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Monthe, O.C.; Grosmaire, L.; Nguimbou, R.M.; Dahdouh, L.; Ricci, J.; Tran, T.; Ndjouenkeu, R. Rheological and textural properties of gluten-free doughs and breads based on fermented cassava, sweet potato and sorghum mixed flours. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 6438, 31002–31008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogdu, A.; Sumnu, G.; Sahin, S. Effects of addition of different fibers on rheological characteristics of cake batter and quality of cakes. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 55, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, H.; Awasthi, P.; Shahi, N.C. Optimization of process variables for preparation of horse gram flour incorporated high fiber nutritious biscuits. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e17170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Sun, D.-W.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Q.-J. Improving freeze tolerance of yeast and dough properties for enhancing frozen dough quality—A review of effective methods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 72, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, W.Y.; Matanjun, P.; Lim, X.X.; Kobun, R. Sensory, Physicochemical, and Cooking Qualities of Instant Noodles Incorporated with Red Seaweed (Eucheuma denticulatum). Foods 2022, 11, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Ahmed, F.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, W. Fresh living Arthrospira as dietary supplements: Current status and challenges. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohani, U.C.; Muthukumarappan, K. Study of continuous flow ultrasonication to improve total phenolic content and antioxidant activity in sorghum flour and its comparison with batch ultrasonication. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 71, 105402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maag, P.; Dirr, S.; Özmutlu Karslioglu, Ö. Investigation of Bioavailability and Food-Processing Properties of Arthrospira platensis by Enzymatic Treatment and Micro-Encapsulation by Spray Drying. Foods 2022, 11, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montevecchi, G.; Santunione, G.; Licciardello, F.; Köker, Ö.; Masino, F.; Antonelli, A. Enrichment of wheat flour with Spirulina. Evaluation of thermal damage to essential amino acids during bread preparation. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Score | Scoring Standard | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Volume (mL/g) | 20 | Specific volume higher than 2.5 mL/g is defined as the full score; for every 0.1 mL/g decrease, 1 point is deducted. | |

| Exterior | Surface Color | 10 | The evaluation criteria for the visual quality of the samples are categorized as follows: Light green, uniform, and glossy samples score between 8.1 and 10 points. Samples that are green, moderately uniform, and exhibit noticeable gloss are rated between 6.1 and 8 points. Conversely, samples that are dark green, uneven, dull, and lack gloss receive scores ranging from 1 to 6 points. This classification allows for a clear and systematic assessment of the samples’ visual characteristics. |

| Surface Smoothness | 10 | The evaluation criteria for the surface smoothness are categorized as follows: a score of 8.1 to 10 points indicates a smooth, wrinkle-free, symmetrical, and firm condition. A score ranging from 6.1 to 8 points reflects moderate smoothness. Conversely, a score between 1 and 6 points denotes roughness, the presence of hard spots, or asymmetry. | |

| Structure | 20 | The evaluation criteria for pore uniformity and resilience are categorized as follows: Fine, uniform pores exhibiting excellent resilience upon finger compression are rated between 16.1 and 20 points. Moderately uniform pores receive a score ranging from 12.1 to 16 points. In contrast, large, uneven pores that demonstrate poor resilience are assigned a score between 1 and 12 points. | |

| Taste | 20 | The evaluation of taste can be categorized into three distinct ranges: a non-sticky texture with a slight spirulina flavor, which scores between 16.1 and 20 points; a moderate spirulina flavor that falls within the range of 12.1 to 16 points; and a sticky texture accompanied by an excessive spirulina flavor, which is rated from 1 to 12 points. This classification provides a clear framework for assessing the sensory attributes of spirulina in various applications. | |

| Flavor | 20 | The evaluation criteria for the aroma and bitterness of the product are categorized as follows: A fresh fermented aroma with no bitterness is rated between 16.1 and 20 points. Mild bitterness is assigned a score ranging from 12.1 to 16 points. In contrast, products exhibiting no fermented aroma but pronounced bitterness are rated between 1 and 12 points. | |

| Total points | 100 | ||

| SP Addition (%) | L* | a* | b* | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 82.74 ± 0.10 a | −2.31 ± 0.03 a | 16.39 ± 0.10 c | 0 a |

| 1 | 57.55 ± 0.30 b | −5.49 ± 0.04 e | 18.46 ± 0.34 ab | 25.48 ± 0.32 b |

| 2 | 51.97 ± 0.54 c | −5.22 ± 0.02 d | 18.94 ± 0.15 a | 31.01 ± 0.54 c |

| 3 | 45.64 ± 0.26 d | −5.54 ± 0.06 e | 17.47 ± 1.22 bc | 37.27 ± 0.24 d |

| 4 | 40.44 ± 0.12 e | −4.53 ± 0.12 c | 16.34 ± 0.41 c | 42.36 ± 0.12 e |

| 5 | 35.59 ± 0.30 f | −3.68 ± 0.14 b | 14.82 ± 0.58 d | 47.20 ± 0.30 f |

| 6 | 33.01 ± 0.47 g | −4.70 ± 0.20 c | 13.53 ± 0.86 e | 49.88 ± 0.47 g |

| SP Addition (%) | Hardness (g) | Springiness | Cohesiveness | Chewiness | Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 389.258 ± 6.61 e | 0.885 ± 0.01 c | 0.805 ± 0.00 a | 283.676 ± 4.09 d | 0.414 ± 0.01 c |

| 1 | 364.300 ± 14.03 e | 0.944 ± 0.00 a | 0.795 ± 0.02 ab | 307.216 ± 6.94 d | 0.430 ± 0.00 b |

| 2 | 536.474 ± 7.70 d | 0.938 ± 0.01 a | 0.784 ± 0.00 abc | 419.002 ± 23.00 c | 0.442 ± 0.00 a |

| 3 | 631.758 ± 37.52 c | 0.920 ± 0.01 b | 0.784 ± 0.00 abc | 456.290 ± 32.00 c | 0.415 ± 0.00 c |

| 4 | 737.711 ± 33.69 b | 0.893 ± 0.00 c | 0.787 ± 0.00 ab | 507.306 ± 23.85 b | 0.420 ± 001 c |

| 5 | 1057.835 ± 57.36 a | 0.890 ± 0.01 c | 0.759 ± 0.00 c | 724.785 ± 47.35 a | 0.398 ± 0.00 d |

| 6 | 1059.251 ± 25.43 a | 0.902 ± 0.01 c | 0.775 ± 0.03 bc | 740.197 ± 36.59 a | 0.411 ± 0.00 c |

| SP Addition (%) | Average Stomatal Area/mm2 | Stomatal Density/(Pieces/cm2) | Porosity/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.44 ± 0.12 d | 83.00 ± 7.07 a | 35.75 ± 6.74 b |

| 1 | 0.48 ± 0.04 cd | 79.00 ± 1.41 a | 37.58 ± 2.26 b |

| 2 | 0.45 ± 0.01 d | 79.00 ± 1.41 a | 35.22 ± 1.61 b |

| 3 | 0.76 ± 0.03 bc | 62.00 ± 2.83 b | 46.95 ± 0.21 a |

| 4 | 0.93 ± 0.01 b | 56.00 ± 0.00 b | 52.05 ± 0.50 a |

| 5 | 1.26 ± 0.28 a | 43.00 ± 7.07 c | 53.05 ± 3.32 a |

| 6 | 1.32 ± 0.07 a | 40.00 ± 2.83 c | 52.66 ± 0.76 a |

| SP Addition (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Protein | 9.61 ± 0.20 g | 10.23 ± 0.17 f | 10.69 ± 0.17 e | 11.23 ± 0.21 d | 11.63 ± 0.10 c | 12.09 ± 0.31 b | 12.82 ± 0.12 a |

| Asp | 0.485 ± 0.01 f | 0.535 ± 0.01 e | 0.683 ± 0.02 d | 0.699 ± 0.01 d | 0.720 ± 0.01 c | 0.745 ± 0.01 b | 0.833 ± 0.00 a |

| Thr | 0.297 ± 0.01 e | 0.340 ± 0.01 d | 0.366 ± 0.01 c | 0.382 ± 0.01 b | 0.384 ± 0.01 b | 0.374 ± 0.01 bc | 0.432 ± 0.01 a |

| Ser | 0.528 ± 0.02 c | 0.628 ± 0.01 b | 0.629 ± 0.02 b | 0.640 ± 0.01 b | 0.645 ± 0.0 b | 0.628 ± 0.01 b | 0.725 ± 0.01 a |

| Glu | 3.659 ± 0.02 b | 3.705 ± 0.05 b | 4.392 ± 0.22 a | 4.400 ± 0.10 a | 4.250 ± 0.14 a | 3.814 ± 0.02 b | 4.430 ± 0.05 a |

| Gly | 0.362 ± 0.00 d | 0.376 ± 0.02 d | 0.475 ± 0.01 b | 0.450 ± 0.02 c | 0.499 ± 0.01 b | 0.486 ± 0.02 b | 0.561 ± 0.00 a |

| Ala | 0.328 ± 0.01 f | 0.371 ± 0.01 e | 0.548 ± 0.01 d | 0.604 ± 0.02 c | 0.608 ± 0.01 c | 0.651 ± 0.01 b | 0.716 ± 0.03 a |

| Cys | 0.969 ± 0.02 d | 0.963 ± 0.01 d | 1.119 ± 0.05 c | 1.231 ± 0.04 b | 1.347 ± 0.02 a | 1.356 ± 0.03 a | 1.372 ± 0.08 a |

| Val | 0.108 ± 0.01 c | 0.121 ± 0.03 bc | 0.126 ± 0.01 abc | 0.138 ± 0.02 abc | 0.145 ± 0.02 ab | 0.131 ± 0.01 abc | 0.155 ± 0.01 a |

| Met | 0.146 ± 0.01 c | 0.148 ± 0.02 c | 0.191 ± 0.00 b | 0.214 ± 0.02 a | 0.211 ± 0.01 ab | 0.213 ± 0.01 a | 0.227 ± 0.02 a |

| Ile | 0.313 ± 0.02 e | 0.347 ± 0.01 d | 0.434 ± 0.01 c | 0.477 ± 0.01 b | 0.465 ± 0.01 b | 0.474 ± 0.02 b | 0.520 ± 0.01 a |

| Leu | 0.682 ± 0.01 d | 0.743 ± 0.02 d | 0.943 ± 0.02 c | 0.998 ± 0.01 bc | 1.069 ± 0.09 ab | 1.011 ± 0.01 bc | 1.118 ± 0.05 a |

| Tyr | 0.209 ± 0.02 e | 0.232 ± 0.01 d | 0.260 ± 0.01 c | 0.280 ± 0.01 bc | 0.297 ± 0.01 ab | 0.315 ± 0.01 a | 0.304 ± 0.01 a |

| Phe | 0.488 ± 0.02 e | 0.507 ± 0.01 e | 0.565 ± 0.02 d | 0.570 ± 0.02 cd | 0.599 ± 0.01 bc | 0.607 ± 0.02 b | 0.704 ± 0.00 a |

| His | 0.277 ± 0.02 c | 0.262 ± 0.00 c | 0.306 ± 0.01 b | 0.307 ± 0.01 b | 0.313 ± 0.01 b | 0.309 ± 0.01 b | 0.361 ± 0.01 a |

| Lys | 0.217 ± 0.01 e | 0.236 ± 0.01 d | 0.303 ± 0.01 c | 0.341 ± 0.02 b | 0.342 ± 0.00 b | 0.343 ± 0.01 b | 0.390 ± 0.01 a |

| Arg | 0.391 ± 0.01 d | 0.401 ± 0.01 d | 0.498 ± 0.01 c | 0.502 ± 0.01 c | 0.512 ± 0.01 c | 0.540 ± 0.02 b | 0.608 ± 0.01 a |

| Pro | 1.175 ± 0.08 d | 1.214 ± 0.07 cd | 1.259 ± 0.04 bcd | 1.280 ± 0.08 bcd | 1.303 ± 0.01 bc | 1.357 ± 0.05 b | 1.531 ± 0.04 a |

| TAA | 10.634 ± 0.30 c | 11.129 ± 0.31 c | 13.097 ± 0.44 b | 13.513 ± 0.38 b | 13.709 ± 0.37 b | 13.354 ± 0.16 b | 14.987 ± 0.34 a |

| EAA | 2.251 ± 0.08 e | 2.442 ± 0.12 d | 2.928 ± 0.05 c | 3.120 ± 0.10 b | 3.215 ± 0.14 b | 3.153 ± 0.07 b | 3.546 ± 0.10 a |

| NEAA | 8.383 ± 0.22 c | 8.687 ± 0.19 c | 10.169 ± 0.38 b | 10.393 ± 0.29 b | 10.494 ± 0.24 b | 10.201 ± 0.09 b | 11.441 ± 0.23 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, K.; Chen, J. Preparation and Quality Evaluation of Steamed Buns with Spirulina Powder. Foods 2025, 14, 4136. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234136

Wang Y, Lyu Y, Xu L, Liu K, Chen J. Preparation and Quality Evaluation of Steamed Buns with Spirulina Powder. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4136. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234136

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yu, Yingguo Lyu, Longxue Xu, Kunlun Liu, and Jie Chen. 2025. "Preparation and Quality Evaluation of Steamed Buns with Spirulina Powder" Foods 14, no. 23: 4136. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234136

APA StyleWang, Y., Lyu, Y., Xu, L., Liu, K., & Chen, J. (2025). Preparation and Quality Evaluation of Steamed Buns with Spirulina Powder. Foods, 14(23), 4136. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234136