Health Risk Assessment of Dietary Chemical Exposures: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Search and Selection

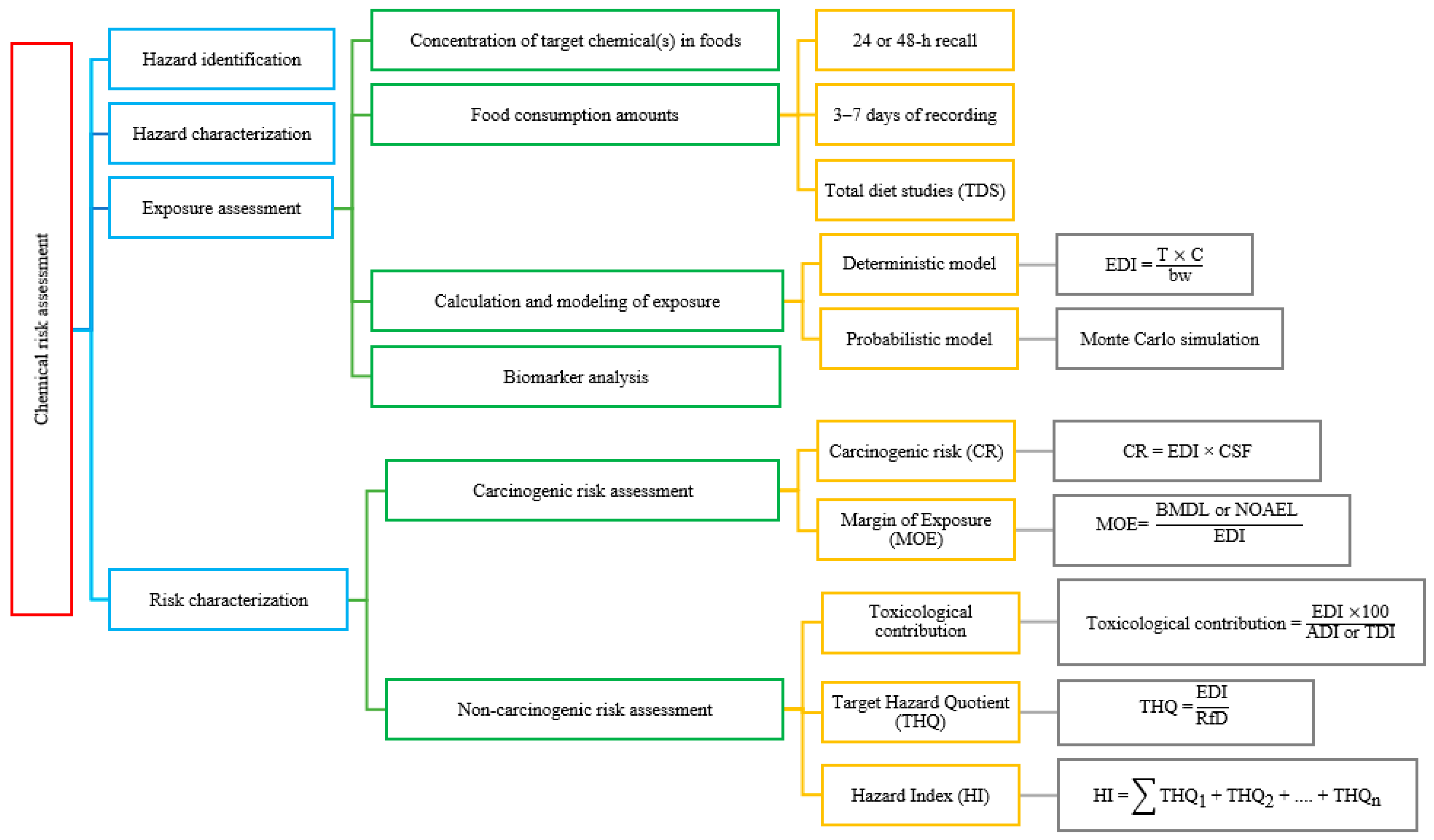

3. Chemical Risk Assessment Process

3.1. Hazard Identification

3.2. Hazard Characterization (Dose–Response Assessment)

3.3. Exposure Assessment

3.3.1. Chemical Concentration in Food Products

3.3.2. Food Consumption Data

Common Dietary Survey Techniques

Population-Based Databases and Screening Tools

Total Diet Study (TDS)

3.3.3. Calculation and Modeling of Exposure

Deterministic (Screening-Level) Exposure Assessment

Probabilistic Exposure Assessment

Biomarker-Based Exposure Assessment

Estimated Daily Intake (EDI)

3.4. Risk Characterization

3.4.1. Carcinogenic Risk (CR) Assessment

3.4.2. Non-CR Assessment

4. Chemicals of Interest in Dietary Exposure Studies

5. International Guidelines and Risk Assessment Approaches

5.1. Codex Alimentarius and FAO/WHO

5.2. EFSA

5.3. US EPA and FDA

5.4. IARC

5.5. Others

6. Current Discussions and Challenges

6.1. Sensitive Groups and Vulnerability

6.2. Cumulative Risk Assessment

6.3. Exposure Variability and Uncertainty

6.4. EDCs and Low-Dose Effects

6.5. Emerging Pollutants

6.6. Effects of Climate Change

6.7. Data Gaps and New Approach Methodologies (NAMs)

6.8. Risk Communication and Perception

7. Future Perspectives

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yazdanfar, N.; Manafi, L.; Ebrahiminejad, B.; Mazaheri, Y.; Sadighara, P.; Basaran, B.; Mohamadi, S. Evaluation of sodium benzoate and potassium sorbate preservative concentrations in different sauce samples in Urmia, Iran. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basaran, B.; Sadighara, P. The level, human exposure, and health risk assessment of acrylamide in chips and breakfast cereals: A study from Türkiye. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 134, 106584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, B.; Turk, H. The levels, single and multiple health risk assessment of 23 metals in enteral nutrition formulas. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 192, 114914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibebu, A.; Tamrat, H.; Bahiru, A. Impact of food safety on global trade. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 10, e1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, D. Burden of foodborne disease in low-income and middle-income countries and opportunities for scaling food safety interventions. Food Secur. 2023, 15, 1475–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.F.; Ahmad, F.A.; Alsayegh, A.A.; Zeyaullah, M.; AlShahrani, A.M.; Muzammil, K.; Saati, A.A.; Wahab, S.; Elbendary, E.Y.; Kambal, N.; et al. Pesticides impacts on human health and the environment with their mechanisms of action and possible countermeasures. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mititelu, M.; Neacșu, S.M.; Busnatu, Ș.S.; Scafa-Udriște, A.; Andronic, O.; Lăcraru, A.E.; Ionită-Mîndrican, C.B.; Lupuliasa, D.; Negrei, C.; Olteanu, G. Assessing heavy metal contamination in food: Implications for human health and environmental safety. Toxics 2025, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muncke, J.; Touvier, M.; Trasande, L.; Scheringer, M. Health impacts of exposure to synthetic chemicals in food. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1431–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyuo, J.; Sackey, L.N.; Yeboah, C.; Kayoung, P.Y.; Koudadje, D. The implications of pesticide residue in food crops on human health: A critical review. Discov. Agric. 2024, 2, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin Karaaslan, M.; Basaran, B. Dietary Acrylamide Exposure and Its Correlation with Nutrition and Exercise Behaviours Among Turkish Adolescents. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. About Codex Alimentarius. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/about-codex/en/#c453333 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Zhu, X.; Wang, M.; Hou, F.; He, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Dai, H.; Huang, M.; Yang, Y.; Wu, L. Multi-residue analysis of pesticides and veterinary drugs by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry using a modified QuEChERS method. Microchem. J. 2025, 208, 112384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, S.A.O.; Sivapriya, T.; Sankarganesh, P. Formation and mitigation of heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in high temperature processed meat products: A review. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, B. Occurrence of Potentially Toxic Metals Detected in Milk and Dairy Products in Türkiye: An Assessment in Terms of Human Exposure and Health Risks. Foods 2025, 14, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić, J.; Lugonja, N.; Knudsen, T.Š.; Marinković, V.; Avdalović, J.; Ilić, M.; Nakano, T. Polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated Diphenyl ethers in infant food: Occurrence and exposure assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 178011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Gandhi, S.; Tripathi, A.D.; Gupta, A.; Iammarino, M.; Sidhu, J.K. Food contamination from packaging material with special focus on the Bisphenol-A. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2025, 45, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCS. Principles and Methods for the Risk Assessment of Chemicals in Food. 2009. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44065/WHO_EHC_240_eng.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- IPCS. Risk Assessment Terminology; International Programme on Chemical Safety, World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- IARC. Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs; IARC: Lyon, France, 2025; Volume 1–139, Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/agents-classified-by-the-iarc/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Bennekou, S.H.; Allende, A.; Bearth, A.; Casacuberta, J.; Castle, L.; Coja, T.; Crépet, A.; Halldorsson, T.; Hoogenboom, L.; Knutsen, H.; et al. EFSA Scientific Committee Statement on the use and interpretation of the margin of exposure approach. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buoso, E.; Masi, M.; Limosani, R.V.; Oliviero, C.; Saeed, S.; Iulini, M.; Passoni, F.C.; Racchi, M.; Corsini, E. Endocrine disrupting toxicity of bisphenol A and Its analogs: Implications in the Neuro-immune milieu. J. Xenobiotics 2025, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, M.; Hou, J. A critical review of presence, removal and potential impacts of endocrine disruptors bisphenol A. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 254, 109275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, B. Estimation of the dietary acrylamide exposure of the Turkish population: An emerging threat for human health. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA; Gergelová, P.; Martino, L.; Rovesti, E. EFSA scientific report on dietary exposure to lead in the European population. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, F.; Fernández, F.R.; Severi, M.; Traversi, R.; Fanos, V.; Street, M.E.; Palanza, P.; Rovero, P.; Papini, A.M. Study of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in Infant Formulas and Baby Bottles: Data from the European life-Milch Project. Molecules 2024, 29, 5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekmezci, H.; Basaran, B. Dietary acrylamide exposure and health risk assessment of pregnant women: A case study from Türkiye. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA. Dietary Exposure (DietEx) Tool. 2022. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-08/dietex-features-instructions.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- EFSA. Food Consumption Data. 2022. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/data-report/food-consumption-data (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- EFSA. Scientific opinion on acrylamide in food. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, B.; Aydin, F. Estimating the acrylamide exposure of adult individuals from coffee: Turkey. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2020, 37, 2051–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Environment Monitoring System (GEMS)/Food Contamination Monitoring and Assessment Programme. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/nutrition-and-food-safety/databases/global-environment-monitoring-system-food-contamination (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Moy, G.G. Total Diet Studies—What They Are and Why They Are Important. In Total Diet Studies; Moy, G., Vannoort, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đokić, M.; Nekić, T.; Varenina, I.; Varga, I.; Solomun Kolanović, B.; Sedak, M.; Čalopek, B.; Vratarić, D.; Bilandžić, N. Pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls in milk and dairy products in Croatia: A health risk assessment. Foods 2024, 13, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Srivastava, S.; Dewangan, J.; Divakar, A.; Kumar Rath, S. Global occurrence of deoxynivalenol in food commodities and exposure risk assessment in humans in the last decade: A survey. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 60, 1346–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, P.; Zhao, F.J. Dietary cadmium exposure, risks to human health and mitigation strategies. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 939–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, F.; Nolasco, A.; Caracciolo, F.; Velotto, S.; Montuori, P.; Romano, R.; Stasi, T.; Cirillo, T. Acrylamide in baby foods: A probabilistic exposure assessment. Foods 2021, 10, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. The principles and methods behind EFSA’s guidance on uncertainty analysis in scientific assessment. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, W.P.; Mutti, A. Role of biomarkers in monitoring exposures to chemicals: Present position, future prospects. Biomarkers 2004, 9, 211–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer-Brolsma, E.M.; Brennan, L.; Drevon, C.A.; van Kranen, H.; Manach, C.; Dragsted, L.O.; Roche, H.M.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Bouwman, J.; et al. Combining traditional dietary assessment methods with novel metabolomics techniques: Present efforts by the Food Biomarker Alliance. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Morata, I.; Sobel, M.; Tellez-Plaza, M.; Navas-Acien, A.; Howe, C.G.; Sanchez, T.R. A state-of-the-science review on metal biomarkers. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2023, 10, 215–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelman, L.; Rodrigues, C.E.; Aleksandrova, K. Effects of dietary patterns on biomarkers of inflammation and immune responses: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastellu, T.; Mondou, A.; Bellouard, M.; Alvarez, J.C.; Le Bizec, B.; Rivière, G. Characterizing the risk related to the exposure to methylmercury over a lifetime: A global approach using population internal exposure. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 187, 114598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. The 2021 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e07939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, G.; Forcucci, F.; Chiarelli, F. Endocrine disruptor chemicals and children’s health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nohmi, T. Thresholds of genotoxic and non-genotoxic carcinogens. Toxicol. Res. 2018, 34, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knutsen, H.K.; Alexander, J.; Barregård, L.; Bignami, M.; Brüschweiler, B.; Ceccatelli, S.; Cottrill, B.; Dinovi, M.; Edler, L.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; et al. Opinion of the Scientific Committee on a request from EFSA related to a harmonised approach for risk assessment of substances which are both genotoxic and carcinogenic. EFSA J. 2005, 3, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Risk Assessment for Carcinogenic Effects. 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/fera/risk-assessment-carcinogenic-effects?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- USEPA. Guidelines for Carcinogen Risk Assessment; EPA/630/P-03/001F; USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. Available online: http://www.epa.gov/cancerguidelines (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). IARC Monographs Evaluate Consumption of Red Meat and Processed Meat; Press Release No. 240, 26 October 2015. Available online: https://www.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/pr240_E.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2015).

- WHO. Cancer: Carcinogenicity of the Consumption of Red Meat and Processed Meat. 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/cancer-carcinogenicity-of-the-consumption-of-red-meat-and-processed-meat (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Başaran, B. An assessment of heavy metal level in infant formula on the market in Turkey and the hazard index. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 105, 104258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, W.; Czop, M.; Iłowiecka, K.; Nawrocka, A.; Wiącek, D. Dietary intake of toxic heavy metals with major groups of food products—Results of analytical determinations. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM); Knutsen, H.K.; Åkesson, A.; Bampidis, V.; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Degen, G.; Hernández-Jerez, A.; Hofer, T.; Hogstrand, C.; et al. Update of the Scientific Opinion on the risks for human health related to the presence of perchlorate in food. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Guidance Manual for Assessing Human Health Risks from Chemically Contaminated, Fish and Shellfish; [EPA-503/8-89-002]; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1989.

- US EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Basic Information About the Integrated Risk Information System. 2021. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/iris/basic-information-about-integrated-risk-information-system (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Dhuldhaj, U.P.; Singh, R.; Singh, V.K. Pesticide contamination in agro-ecosystems: Toxicity, impacts, and bio-based management strategies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 9243–9270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, S.M.; Ray, A.K.; Barghi, S. Water pollution and agriculture pesticide. Clean Technol. 2022, 4, 1088–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd, G.I.; Salih, M.A.J.; Ahmed, H.E.; Alani, M.H.; Abed, B.M. The Role of Chemical Pesticides in Environmental Pollution and Ecological Imbalance. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2025; Volume 1449, No. 1; p. 012145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, H.Y.; Wang, X.D.; Lv, Y.F.; Wei, N. Application of QuEChERS for analysis of contaminants in dairy products: A review. J. Food Prot. 2025, 88, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, A.; Tucho, G.T.; Gure, A.; Mekonen, S. Pesticide exposure and acute health problems among pesticide processing industry workers in Ethiopia. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 101997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, A.; Pawar, S.; Patil, M.S.; Kale, S.R.; Patil, S. A scientific review of pesticides: Classification, toxicity, health effects, sustainability, and environmental impact. Cureus 2024, 16, e67945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cestonaro, L.V.; Macedo, S.M.D.; Piton, Y.V.; Garcia, S.C.; Arbo, M.D. Toxic effects of pesticides on cellular and humoral immunity: An overview. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2022, 44, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Nian, B.; Yu, C.; Maimaiti, D.; Chai, M.; Yang, X.; Zang, X.; Xu, D. Mechanisms of neurotoxicity of organophosphate pesticides and their relation to neurological disorders. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2024, 2024, 2237–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwamahoro, C.; Jo, J.H.; Jang, S.I.; Jung, E.J.; Lee, W.J.; Bae, J.W.; Kwon, W.S. Assessing the risks of pesticide exposure: Implications for endocrine disruption and male fertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afsheen, S.; Rehman, A.S.; Jamal, A.; Khan, N.; Parvez, S. Understanding role of pesticides in development of Parkinson’s disease: Insights from Drosophila and rodent models. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 98, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felisbino, K.; da Silva Milhorini, S.; Kirsten, N.; Bernert, K.; Schiessl, R.; Guiloski, I.C. Exposure to pesticides during pregnancy and the risk of neural tube defects: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angon, P.B.; Islam, M.S.; Das, A.; Anjum, N.; Poudel, A.; Suchi, S.A. Sources, effects and present perspectives of heavy metals contamination: Soil, plants and human food chain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saidon, N.B.; Szabó, R.; Budai, P.; Lehel, J. Trophic transfer and biomagnification potential of environmental contaminants (heavy metals) in aquatic ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 340, 122815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munir, N.; Jahangeer, M.; Bouyahya, A.; El Omari, N.; Ghchime, R.; Balahbib, A.; Aboulaghras, S.; Mahmood, Z.; Akram, M.; Shah, S.M.A.; et al. Heavy metal contamination of natural foods is a serious health issue: A review. Sustainability 2021, 14, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Vashishth, R. From water to plate: Reviewing the bioaccumulation of heavy metals in fish and unraveling human health risks in the food chain. Emerg. Contam. 2024, 10, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, V.I.; Hendricks, M.; Jones, K.S. Lead toxicity in children: An unremitting public health problem. Pediatr. Neurol. 2020, 113, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrjerdi, F.Z.; Raeini, A.S.; Zebhi, F.S.; Hafizi, Z.; Mirjalili, R.; Aghda, F.A. Berberine hydrochloride improves cognitive function and hippocampal antioxidant status in subchronic and chronic lead poisoning. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2025, 31, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.S.; Osman, A.I.; Hosny, M.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Rooney, D.W.; Chen, Z.; Rahim, N.S.; Sekar, M.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; et al. The toxicity of mercury and its chemical compounds: Molecular mechanisms and environmental and human health implications: A comprehensive review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 5100–5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.A.; Moglad, E.; Bansal, P.; Kaur, H.; Deorari, M.; Thapa, R.; Almalki, W.H.; Kazmi, I.; Alzarea, S.I.; Kukreti, N.; et al. Pollutants to pathogens: The role of heavy metals in modulating TGF-β signaling and lung cancer risk. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2024, 256, 155260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, K.; Mastali, G.; Abbasgholinejad, E.; Bafrani, M.A.; Shahmohammadi, A.; Sadri, Z.; Zahed, M.A. Cadmium Neurotoxicity: Insights into Behavioral Effect and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garkal, A.; Sarode, L.; Bangar, P.; Mehta, T.; Singh, D.P.; Rawal, R. Understanding arsenic toxicity: Implications for environmental exposure and human health. J. Hazard. Mater. Lett. 2024, 5, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ali, M.; Raj, V.; Kumari, A.; Rachamalla, M.; Niyogi, S.; Kumar, D.; Sharma, A.; Saxena, A.; Panjawani, G.; et al. Arsenic causing gallbladder cancer disease in Bihar. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanajou, S.; Erkekoğlu, P.; Şahin, G.; Baydar, T. Role of aluminum exposure on Alzheimer’s disease and related glycogen synthase kinase pathway. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 46, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryliński, Ł.; Kostelecka, K.; Woliński, F.; Duda, P.; Góra, J.; Granat, M.; Flieger, J.; Teresiński, G.; Buszewicz, G.; Sitarz, R.; et al. Aluminium in the human brain: Routes of penetration, toxicity, and resulting complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossini, H.; Shafie, B.; Niri, A.D.; Nazari, M.; Esfahlan, A.J.; Ahmadpour, M.; Nazmara, Z.; Ahmadimanesh, M.; Makhdoumi, P.; Mirzaei, N.; et al. A comprehensive review on human health effects of chromium: Insights on induced toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 70686–70705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, W.; Rai, S.; Banerjee, S.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Mondal, M.H.; Bhattarai, A.; Saha, B. A comprehensive review on the sources, essentiality and toxicological profile of nickel. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 9139–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linna, A.; Uitti, J.; Oksa, P.; Toivio, P.; Virtanen, V.; Lindholm, H.; Halkosaari, M.; Sauni, R. Effects of occupational cobalt exposure on the heart in the production of cobalt and cobalt compounds: A 6-year follow-up. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamle, M.; Mahato, D.K.; Gupta, A.; Pandhi, S.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, B.; Mishra, S.; Arora, S.; Selvakumar, R.; Saurabh, V.; et al. Citrinin mycotoxin contamination in food and feed: Impact on agriculture, human health, and detection and management strategies. Toxins 2022, 14, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.; Soni, H.; Tandon, S.; Singh, G.; Gandhi, Y.; Kumar, V.; Jagtap, C.; Narasimhaji, C.V.; Mathapati, S.; Srikanth, N.; et al. Fungal Toxin (Mycotoxin): Introduction, Sources and Types, Production, Detection, and Applications. Food Nutr. 2025, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sufar, E.K.; Bernhoft, A.; Seal, C.; Rempelos, L.; Hasanaliyeva, G.; Zhao, B.; Iversen, P.O.; Baranski, M.; Volakakis, N.; et al. Mycotoxin contamination in organic and conventional cereal grain and products: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fovo, F.P.; Maeda, D.G.; Kaale, L.D. Microbiological approaches for mycotoxin decontamination in foods and feeds to enhance food security: A review. Mycotoxin Res. 2025, 41, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abia, W.A.; Foupouapouognigni, Y.; Nfombouot, H.P.N.; Ngoungoure, L.V.N.; Ntungwe, E.N.; Salah-Abbès, J.B.; Tchana, A.N. A scoping review on mycotoxin-induced neurotoxicity. Discov. Toxicol. 2025, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, A.A.; Shi, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, L.; Abdel-Galil, M.; Salem, S.H.; Ayad, E.G.; Deabes, M.; et al. Global health and economic impacts of mycotoxins: A comprehensive review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemede, H.F. Toxicity, Mitigation, and Chemical Analysis of Aflatoxins and Other Toxic Metabolites Produced by Aspergillus: A Comprehensive Review. Toxins 2025, 17, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Wen, D.; Guo, P.; Xiong, J.; Qiu, Y. Effects of Dietary Baicalin on Aflatoxin B1-Induced Growth Performance and Liver Health in Ducklings. Animals 2025, 15, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmorsy, E.M.; Doghaither, H.A.A.; Al-Ghafari, A.B.; Alyamani, S.A.; Mohammed, Z.M.; Ebrahim, N.A.; Elshopakey, G.E.; Shabana, S.M. Through its genoprotective, mitochondrial bioenergetic modulation, and antioxidant effects, Fucoxanthin and its metabolite minimize Ochratoxin A-induced nephrotoxicity in HK-2 human kidney cells. BMC Nephrol. 2025, 26, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Esparza, M.Á.; Mateo, E.M.; Robles, J.A.; Capoferri, M.; Jiménez, M.; Soria, J.M. Unveiling the Neurotoxic Effects of Ochratoxin A and Its Impact on Neuroinflammation. Toxins 2025, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anumudu, C.K.; Ekwueme, C.T.; Uhegwu, C.C.; Ejileugha, C.; Augustine, J.; Okolo, C.A.; Onyeaka, H. A review of the mycotoxin family of fumonisins, their biosynthesis, metabolism, methods of detection and effects on humans and animals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 26, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwomadu, T.I.; Akinola, S.A.; Mwanza, M. Fusarium mycotoxins, their metabolites (free, emerging, and masked), food safety concerns, and health impacts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, E.; Lu, Y.; Liu, B.; Yan, K.; Yang, X.; Lv, H. Trichothecenes toxicity in humans and animals: Unraveling the mechanisms and harnessing phytochemicals for prevention. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 296, 110226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak-Śliwińska, M.; Paszczyk, B. Trichothecenes in food and feed, relevance to human and animal health and methods of detection: A systematic review. Molecules 2021, 26, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuchi, C.G.; Ondari, E.N.; Ogbonna, C.U.; Upadhyay, A.K.; Baran, K.; Okpala, C.O.R.; Korzeniowska, M.; Guiné, R.P. Mycotoxins affecting animals, foods, humans, and plants: Types, occurrence, toxicities, action mechanisms, prevention, and detoxification strategies—A revisit. Foods 2021, 10, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanati, K.; Basaran, B.; Abedini, A.; Akbari-Adergani, B.; Akbari, N.; Sadighara, P. Zearalenone, an estrogenic component, in bovine milk, amount and detection method; A systematic review and meta-analysis. Toxicol. Rep. 2024, 13, 101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Carrasco Cabrera, L.; Di Piazza, G.; Dujardin, B.; Marchese, E.; Medina Pastor, P. The 2023 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ten Chemicals of Public Health Concern. 2010. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/photo-story/detail/10-chemicals-of-public-health-concern (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- European Union. Communication from the Commission—On Effective, Accessible and Resilient Social Rights. Official Journal of the European Union. 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014H0193 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation (EU) 2015/1381 of 10 August 2015 on the Monitoring of Arsenic in Food; European Commission: Brussel, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. In Proceedings of the Summary and Conclusions—72nd Meeting, Rome, Italy, 16–25 February 2010; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/c5db0dca-82f4-4c98-847c-b3617beb778e (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. China: China Releases the Standard for Maximum Levels of Contaminants in Foods. 2018. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/china-china-releases-standard-maximum-levels-contaminants-foods (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/1005 of 25 June 2015 Amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 as Regards Maximum Levels of Lead in Certain Foodstuffs (Text with EEA Relevance). 2015. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2015/1005/oj/eng (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). In Proceedings of the 38th Session of the Codex Alimentarius Commission, Geneva, Switzerland, 6–11 July 2015. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/international-affairs/international-standards/codex-alimentarius/codex-alimentarius-commission_en (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation No 2013/165/EU of 27 March 2013 on the presence of T-2 and HT-2 toxin in cereals and cereal products. Off. J. Eur. Union 2013, 91, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Serbian Regulation. Maximum Allowed Contents of Contaminants in Food and Feed, 28/11; Official Bulletin of the Republic Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2011; pp. 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kos, J.; Anić, M.; Radić, B.; Zadravec, M.; Janić Hajnal, E.; Pleadin, J. Climate change—A global threat resulting in increasing mycotoxin occurrence. Foods 2023, 12, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casu, A.; Camardo Leggieri, M.; Toscano, P.; Battilani, P. Changing climate, shifting mycotoxins: A comprehensive review of climate change impact on mycotoxin contamination. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzec-Schmidt, K.; Börjesson, T.; Suproniene, S.; Jędryczka, M.; Janavičienė, S.; Góral, T.; Karlsson, I.; Kochiieru, Y.; Ochodzki, P.; Mankevičienė, A.; et al. Modelling the effects of weather conditions on cereal grain contamination with deoxynivalenol in the Baltic Sea Region. Toxins 2021, 13, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okorski, A.; Milewska, A.; Pszczółkowska, A.; Karpiesiuk, K.; Kozera, W.; Dąbrowska, J.A.; Radwińska, J. Prevalence of Fusarium fungi and deoxynivalenol levels in winter wheat grain in different climatic regions of Poland. Toxins 2022, 14, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Mycotoxin Exposure in a Changing European Climate; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/mycotoxin-exposure-in-a-changing-european-climate (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Nada, S.; Nikola, T.; Bozidar, U.; Ilija, D.; Andreja, R. Prevention and practical strategies to control mycotoxins in the wheat and maize chain. Food Control 2022, 136, 108855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matumba, L.; Namaumbo, S.; Ngoma, T.; Meleke, N.; De Boevre, M.; Logrieco, A.F.; De Saeger, S. Five keys to prevention and control of mycotoxins in grains: A proposal. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 30, 100562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yu, X.; Tian, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhuang, P.; Jia, W.; Zhang, Y. Joint control of multiple food processing contaminants in Maillard reaction: A comprehensive review of health risks and prevention. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraju, I.; Sana, M.; Chakraborty, I.; Rahman, M.H.; Biswas, R.; Mazumder, N. Dietary acrylamide: A detailed review on formation, detection, mitigation, and its health impacts. Foods 2024, 13, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunita, C.N.; Rahayu, P.P. Citrus Marinades as a Natural Strategy to Improve the Physicochemical Quality and Safety of Grilled Meat: A Review. BIO Web Conf. 2025, 191, 00026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhang, J.; Gao, X.; Zhou, Y. The Food Contaminants Chloropropanols and Chloropropanol Esters: A Review. J. Food Biochem. 2025, 2025, 4846670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Baadani, W.A.; Al-Samman, A.M.M.A.; Anantacharya, R.; Satyanarayan, N.D.; Siddique, N.A.; Maqati, A.A. Cytotoxicity effect and antioxidant potential of 5-Hydroxymethyl Furfural (5-HMF) analogues: An advance approach. J. Phytol. 2024, 16, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopańska, M.; Łagowska, A.; Kuduk, B.; Banaś-Ząbczyk, A. Acrylamide neurotoxicity as a possible factor responsible for inflammation in the cholinergic nervous system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobets, T.; Smith, B.P.; Williams, G.M. Food-borne chemical carcinogens and the evidence for human cancer risk. Foods 2022, 11, 2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamri, M.; Walmsley, S.J.; Turesky, R.J. Metabolism and biomarkers of heterocyclic aromatic amines in humans. Genes Environ. 2021, 43, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Marchand, L. The role of heterocyclic aromatic amines in colorectal cancer: The evidence from epidemiologic studies. Genes Environ. 2021, 43, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.N.; Zeng, Y.; Zhu, L.; Pan, J.J.; Wu, S.L.; Li, D.; Dong, B.; Li, H.K.; Wang, X.H.; Zhang, H.; et al. The occurrence of Mono/Di-Chloropropanol contaminants in food contact papers and their potential health risk. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 34, 101002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabani, D.S.; Ofosu, I.W.; Ankar-Brewoo, G.M.; Lutterodt, H.E. Toxicity of Dietary Exposure to 3—Monochloropropanediol, Glycidol, and Their Fatty Acid Esters. J. Food Qual. 2024, 2024, 7913820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, P.; Chen, H.; Guo, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, T.; Yao, D.; Li, X.; Liu, B.; Yuan, J. Revealing toxic secrets: How PAHs accelerate cellular ageing and trigger human diseases. Toxicology 2025, 517, 154219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F., Jr.; Rocha, B.A.; Souza, M.C.; Bocato, M.Z.; Azevedo, L.F.; Adeyemi, J.A.; Santana, A.; Campiglia, A.D. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): Updated aspects of their determination, kinetics in the human body, and toxicity. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2023, 26, 28–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, C.; Long, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, G. Food additives: From functions to analytical methods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 8497–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, M. Food chemistry: Role of additives, preservatives, and adulteration. In Food Chemistry: The Role of Additives, Preservatives and Adulteration; Scrivener Publishing LLC: Beverly, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez-Méndez, J.; López, J. Food Additives: Importance, Classification, and Adverse Reactions in Humans. In Natural Additives in Foods; Valencia, G.A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal-Dembowska, A.; Jarmakiewicz-Czaja, S.; Tabarkiewicz, J.; Filip, R. Nitrate and Nitrite in the Diet: Protective and Harmful Effects in Health and Disease. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2025, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, E.F.; Burleigh, M.; Mira, A.; Van Breda, S.G.J.; Weitzberg, E.; Rosier, B.T. Nitrate: “the source makes the poison”. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 4676–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M.H.; Trisha, A.T.; Rahman, M.; Talukdar, S.; Kobun, R.; Huda, N.; Zzaman, W. Nitrites in cured meats, health risk issues, alternatives to nitrites: A review. Foods 2022, 11, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.K. Neurological reaction to food additives: Neurotoxic effects of food additives. In Food Additives-From Chemistry to Safety; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, P.; Mohammadi, A.; Mohammadzadeh-Aghdash, H.; Dolatabadi, J.E.N. Pharmacokinetic and toxicological aspects of potassium sorbate food additive and its constituents. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 80, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Olmo, A.; Calzada, J.; Nuñez, M. Benzoic acid and its derivatives as naturally occurring compounds in foods and as additives: Uses, exposure, and controversy. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3084–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak-Nowicka, Ł.J.; Herbet, M. Sodium benzoate—Harmfulness and potential use in therapies for disorders related to the nervous system: A review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaher, S.A.A.; Mihailescu, D.F.; Amuzescu, B. Aspartame safety as a food sweetener and related health hazards. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnecka, K.; Pilarz, A.; Rogut, A.; Maj, P.; Szymańska, J.; Olejnik, Ł.; Szymański, P. Aspartame—True or false? Narrative review of safety analysis of general use in products. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, J.O. Artificial food additives: Hazardous to long-term health? Arch. Dis. Child. 2024, 109, 882–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, D.; Millet, M.; Jabali, Y.; Delhomme, O. Occurrence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Fogwater at Urban, Suburban, and Rural Sites in Northeast France between 2015 and 2021. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te, B.; Yiming, L.; Tianwei, L.; Huiting, W.; Pengyuan, Z.; Wenming, C.; Jun, J. Polychlorinated biphenyls in a grassland food network: Concentrations, biomagnification, and transmission of toxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 709, 135781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Yuan, Y.; Yin, H.; Guo, Z.; Wei, X.; Qi, X.; Liu, H.; Dang, Z. Environmental contamination and human exposure of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in China: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motamedi, M.; Yerushalmi, L.; Haghighat, F.; Chen, Z. Recent developments in photocatalysis of industrial effluents: A review and example of phenolic compounds degradation. Chemosphere 2022, 296, 133688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmayya, N.S.; Panday, A.; Yadavalli, R.; Reddy, C.N.; Mandal, S.K.; Agrawal, D.C.; Mishra, B. Food contamination with micro-plastics: Occurrences, bioavailability, human vulnerability, and prevention. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2024, 20, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, G.; Yazdanfar, N.; Shariatifar, N.; Molaee-Aghaee, E.; Sadighara, P. Health Risk Assessment and Determination of Bisphenol A and Aflatoxin M1 in Infant Formula. BMC Nutr. 2025, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massahi, T.; Omer, A.K.; Kiani, A.; Soleimani, H.; Fattahi, N.; Sharafi, K. Assessing the effect of sunlight exposure and reuse of polyethylene terephthalate bottles on phthalate migration. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 962, 178480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauskopf, J.; Eggermont, K.; Caiment, F.; Verfaillie, C.; de Kok, T.M. Molecular insights into PCB neurotoxicity: Comparing transcriptomic responses across dopaminergic neurons, population blood cells, and Parkinson’s disease pathology. Environ. Int. 2024, 186, 108642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari, E.; Noorimotlagh, Z.; Mirzaee, S.A.; Nourmoradi, H.; Bahmani, M.; Rashan, N.; Martinez, S.S.; Kamran, S.; Ahmadi, I. Establishing the Mechanisms Involved in the Environmental Exposure to Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) in the Risk of Male Infertility. Reprod. Sci. 2025, 32, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, L.; Pironti, C.; Pinto, G.; Ricciardi, M.; Buono, A.; Brogna, C.; Venier, M.; Piscopo, M.; Amoresano, A.; Motta, O. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the environment: Occupational and exposure events, effects on human health and fertility. Toxics 2022, 10, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, J.L.; Nadal, M. PCDD/Fs in human tissues: A review of global biomonitoring data. Chemosphere 2025, 377, 144345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vito, M.; Bokkers, B.; van Duursen, M.B.; van Ede, K.; Feeley, M.; Gáspár, E.A.F.; Haws, L.; Kennedy, S.; Peterson, R.E.; Hoogenboom, R.; et al. The 2022 world health organization reevaluation of human and mammalian toxic equivalency factors for polychlorinated dioxins, dibenzofurans and biphenyls. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 146, 105525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Gao, Y.; Xia, Y.; Sun, P.; Qin, W. Investigating the impact of dioxins, furans, and coplanar polychlorinated biphenyls on mortality, inflammatory states, and chronic diseases: An integrative epidemiological analysis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 289, 117463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, C.; Jeung, E.B. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and disease endpoints. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Hong, S.J.; Park, Y.J.; Baek, I.H. Association between phthalate exposure and risk of allergic rhinitis in children: A systematic review and meta—Analysis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 35, e14230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dualde, P.; León, N.; Sanchis, Y.; Corpas-Burgos, F.; Fernández, S.F.; Hernández, C.S.; Saez, G.; Pérez-Zafra, E.; Mora-Herranz, A.; Pardo, O.; et al. BIOVAL Task Force. Biomonitoring of phthalates, bisphenols and parabens in children: Exposure, predictors and risk assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, Z.; Song, M.; Ikram, S.; Zahra, Z. Overview of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), their applications, sources, and potential impacts on human health. Pollutants 2024, 4, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassano, M.; Seyyedsalehi, M.S.; Kappil, E.M.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, T.; Boffetta, P. Exposure to per-and poly-fluoroalkyl substances and lung, head and neck, and thyroid cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2025, 266, 120606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, W.; Li, J.; Luo, L.; Peng, W.; Wang, X.; Jin, R.; Li, J. Triglycerides mediate the relationships of per-and poly-fluoroalkyl substance (PFAS) exposure with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) risk in US participants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 289, 117436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, S.; Shah, S.T.A.; Mamoulakis, C.; Docea, A.O.; Kalantzi, O.I.; Zachariou, A.; Calina, D.; Carvalho, F.; Sofikitis, N.; Makrigiannakis, A.; et al. Endocrine disruptors acting on estrogen and androgen pathways cause reproductive disorders through multiple mechanisms: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funari Junior, R.A.; Frescura, L.M.; de Menezes, B.B.; da Rosa, M.B. 4-Nonylphenol adsorption, environmental impact and remediation: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2025, 23, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.H.; Jang, J.H.; Cho, H.Y.; Lee, Y.B. Human risk assessment of 4-n-nonylphenol (4-n-NP) using physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling: Analysis of gender exposure differences and application to exposure analysis related to large exposure variability in population. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 96, 2687–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, S.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, R.; Zhang, X.; El-Mesery, H.S.; Dai, X.; Lu, W.; Xu, R. Exploring Formation and Control of Hazards in Thermal Processing for Food Safety. Foods 2025, 14, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahir, A.; Khan, I.A.; Nasim, M.; Azizi, M.N.; Azi, F. Food process contaminants: Formation, occurrence, risk assessment and mitigation strategies—A review. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2024, 41, 1242–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami-Borujeni, F.; Mortezazadeh, F.; Hoseinvandtabar, S.; Mohseni-Bandpei, A.; Niknejad, H. Health risks assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in meat kebabs through meta-analysis and Monte Carlo simulation. MethodsX 2025, 15, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesias, M.; González-Mulero, L.; Morales, F.J.; Delgado-Andrade, C. Acrylamide intake in senior center canteens: A total exposure assessment applying the duplicate diet approach. Foods 2025, 14, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, B.; Anlar, P.; Oral, Z.F.Y.; Polat, Z.; Kaban, G. Risk assessment of acrylamide and 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural (5-HMF) exposure from bread consumption: Turkey. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 107, 104409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, W.; Ji, J.; Chen, F.; Liao, X.; Hu, X.; Ma, L. Heterocyclic amines in meat and meat products: Occurrence, formation, mitigation, health risks and intervention. Food Rev. Int. 2024, 40, 1503–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourson, M.L. Let the IRIS Bloom: Regrowing the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 97, A4–A5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. Evaluation of Certain Contaminants in Food: Seventy-Second Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives; WHO Technical Report Series; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; p. 959. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Safety Evaluation of Certain Food Additives; WHO Technical Report Series; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240100978 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). (n.d.). Food Additives. EFSA. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/food-additives (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- McMahon, N.F.; Brooker, P.G.; Pavey, T.G.; Leveritt, M.D. Nitrate, nitrite and nitrosamines in the global food supply. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 2673–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, J.L.; Nadal, M. Carcinogenicity of Consumption of Red Meat and Processed Meat: A Review of Scientific News since the IARC Decision. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 105, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Evaluation of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants: Eightieth Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives; WHO Technical Report Series 995; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 9789240695405. [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). IARC Monographs Volume 134: Aspartame Classified as Possibly Carcinogenic to Humans (Group 2B). 2023. Available online: https://www.iarc.who.int/news-events/iarc-monographs-volume-134-aspartame-methyleugenol-and-isoeugenol/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA). Safety Evaluation of Certain Food Additives: Prepared by the Ninety-Sixth Meeting of JECFA (JECFA Monograph); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.D.; Steinmaus, C.; Golub, M.S.; Castorina, R.; Thilakartne, R.; Bradman, A.; Marty, M.A. Potential impacts of synthetic food dyes on activity and attention in children: A review of the human and animal evidence. Environ. Health 2022, 21, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, Z.B.; Silva da Costa, D.V.; da Silva dos Santos, A.C.; da Silva Júnior, A.Q.; de Lima Silva, A.; de Santana, R.C.F.; Costa, I.C.G.; de Sousa Ramos, S.F.; Padilla, G.; da Silva, S.K.R. Synthetic colors in food: A warning for children’s health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitanya, M.V.N.L.; Arora, S.; Pal, R.S.; Ali, H.S.; El Haj, B.M.; Logesh, R. Assessment of environmental pollutants for their toxicological effects of human and animal health. In Organic Micropollutants in Aquatic and Terrestrial Environments; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehouel, F.; Giovanni Uc-Peraza, R.; Rose, M.; Squadrone, S. Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins/dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs) and dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls (DL-PCBs) in some foods of animal origin in some countries of the world: A review. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2025, 42, 1065–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüce, B.; Güzel, B.; Canlı, O.; Öktem Olgun, E.; Kaya, D.; Aşçı, B.; Murat Hocaoğlu, S. Comprehensive research and risk assessment on the pollution profile of organic micropollutants (OMPs) in different types of citrus essential oils produced from waste citrus peels in Türkiye. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 142, 107463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malisch, R.; Kotz, A. Dioxins and PCBs in feed and food—Review from European perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 491, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogenboom, R.; Traag, W.; Fernandes, A.; Rose, M. European developments following incidents with dioxins and PCBs in the food and feed chain. Food Control 2015, 50, 670–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorini, F.; Tonacci, A.; Sanmartin, C.; Venturi, F. Phthalates and non-phthalate plasticizers and thyroid dysfunction: Current evidence and novel strategies to reduce their spread in food industry and environment. Toxics 2025, 13, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Ma, B.; Wang, L.; Tao, W. Occurrence and dietary exposure risks of phthalate esters in food in the typical valley city Xi’an, Northwest China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 31426–31440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzen, M.; Mortazavian, A.M.; Shariatifar, N.; Sohrabvandi, S.; Khanniri, E.; Arabameri, M. Investigation of PAEs in some dairy products (yogurt and kashk) using method of MSPE-GC/MS: A health risk assessment study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 65393–65405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velotto, S.; Squillante, J.; Nolasco, A.; Romano, R.; Cirillo, T.; Esposito, F. Occurrence of phthalate esters in coffee and risk assessment. Foods 2023, 12, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumu, K.; Vorst, K.; Curtzwiler, G. Endocrine modulating chemicals in food packaging: A review of phthalates and bisphenols. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 1337–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadac-Czapska, K.; Bukowska, B.; Sicińska, P.; Grembecka, M. Hidden Threats in Infant Diets and Environment: Risks of Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Food. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2025, 263, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation. Commission Regulation (EU) 2018/213 of 12 February 2018 on the Use of Bisphenol a in Varnishes and Coatings Intended to Come into Contact with Food and Amending Regulation (EU) No 10/2011 as Regards the Use of That Substance in Plastic Food Contact Materials; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Panieri, E.; Baralic, K.; Djukic-Cosic, D.; Buha Djordjevic, A.; Saso, L. PFAS molecules: A major concern for the human health and the environment. Toxics 2022, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez Carnero, A.; Lestido-Cardama, A.; Vazquez Loureiro, P.; Barbosa-Pereira, L.; Rodríguez Bernaldo de Quirós, A.; Sendón, R. Presence of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in food contact materials (FCM) and its migration to food. Foods 2021, 10, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/2388 of 7 December 2022 Amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 as Regards Maximum Levels of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Certain Foodstuffs (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2022/2388/oj/eng (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Abedini, A.; Hadian, Z.; Kamalabadi, M.; Salimi, M.; Koohy-Kamaly, P.; Basaran, B.; Sadighara, P. Melamine and cyanuric acid in milk and their quantities, analytical methods and exposure risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Food Prot. 2025, 88, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitakwa, N.; Alqudaimi, M.; Sultan, M.; Wu, D. Plastic-related endocrine disrupting chemicals significantly related to the increased risk of estrogen-dependent diseases in women. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, J.; Guo, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Ge, H.; Li, X.Y. Occurrence and emission of phthalates, bisphenol A, and oestrogenic compounds in concentrated animal feeding operations in Southern China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 207, 111521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; WHO. Working Principles for Risk Analysis for Application in the Framework of the Codex Alimentarius. In Codex Alimentarius Commission Procedural Manual; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- van der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; van Asselt, E.D.; Raley, M.; Poulsen, M.; Korsgaard, H.; Bredsdorff, L.; Nauta, M.; Flari, V.; d’Agostino, M.; Coles, D.; et al. Critical Review of Methodology and Application of Risk Ranking for Prioritisation of Food and Feed Related Issues, on the Basis of the Size of Anticipated Health Impact. EFSA Support. Publ. 2015, 12, 710E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint FAO/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues (JMPR). JMPR Summary Report; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/food-safety/jmpr/jmpr-summary-report-2024.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA). (2023 2024, 29 Aralık). Evaluation of Certain Food Additives: Ninety-Sixth Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. WHO Technical Report Series; 1050. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240083059 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority. Cumulative risk assessment with pesticides in the European Union—Proposed work programme 2024–2026. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e211009. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority. Prioritisation of pesticides and target organ systems for cumulative risk assessment. EFSA J. 2024, 22, 8554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Re-evaluation of silicon dioxide (E 551) as a food additive. EFSA J. 2024, 16, 8880. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority. Scientific opinion on the tolerable upper intake level for preformed vitamin A and β-carotene. EFSA J. 2024, 22, 8814. [Google Scholar]

- Judson, R.; Richard, A.; Dix, D.J.; Houck, K.; Martin, M.; Kavlock, R.; Dellarco, V.; Henry, T.; Holderman, T.; Sayre, P.; et al. The Toxicity Data Landscape for Environmental Chemicals. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. EPA’s Approach for Assessing the Risks Associated with Chronic Exposure to Carcinogens. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/iris/epas-approach-assessing-risks-associated-chronic-exposure-carcinogens (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Food Packaging & Other Substances That Come in Contact with Food: Information for Consumers. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/food-packaging-other-substances-come-contact-food-information-consumers (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/generally-recognized-safe-gras (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- IARC. IARC Monographs Hazard Classification [Infographic]; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.iarc.who.int/infographics/iarc-monographs-classification/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Pearce, N.; Blair, A.; Vineis, P.; Ahrens, W.; Andersen, A.; Anto, J.M.; Armstrong, B.K.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Beland, F.A.; Berrington, A.; et al. IARC Monographs: 40 Years of Evaluating Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 507–5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Yamazaki, T.; Sato, H. Risk assessment of food contact materials: Tiered approach in the guidelines of FSCJ. Food Saf. 2022, 10, D-21-00029. Available online: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/foodsafetyfscj/10/2/10_D-21-00029/_html/-char/ja (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. How FSANZ Ensures the Safety of Food Additives. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/additives/additivecontrol (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Yang, D.; Liu, X.; Zhao, W. Advancing Food Safety Risk Assessment in China. Frontiers in Food Science. 2023. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10690935 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Ng, S.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Food safety risk-assessment systems utilized by China and Australia/New Zealand: A comparative review. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 5094–5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Craig, P.S.; Dujardin, B.; Hart, A.; Hernández-Jerez, A.F.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Kneuer, C.; Ossendorp, B.; Pedersen, R.; Wolterink, G.; et al. Cumulative dietary risk characterisation of pesticides that have acute effects on the nervous system. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Craig, P.S.; Dujardin, B.; Hart, A.; Hernandez-Jerez, A.F.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Kneuer, C.; Ossendorp, B.; Pedersen, R.; Wolterink, G.; et al. Cumulative dietary risk characterisation of pesticides that have chronic effects on the thyroid. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Revised OP (Organophosphate) Cumulative Risk Assessment. 2002. Available online: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyNET.exe/9100BFLL.TXT?ZyActionD=ZyDocument (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Fang, H.; Wang, H.; Zeng, C.; Fu, H.; Zhao, B.; Liu, A.; Yan, J. A preliminary cumulative risk assessment of Diethylhexyl phthalate and Dibutyl phthalate based on the inhibition of embryonic development via the PPARγ pathway. Toxicol. Vitr. 2022, 84, 105430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo, C.; Dumitrascu, C.; More, S.J. Risk assessment of combined exposure to multiple chemicals at the European Food Safety Authority: Principles, guidance documents, applications and future challenges. Toxins 2023, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, M.A.; Rusu, C.; Danci, M.; Dronca, D. Human health impact based on adult European consumers’ dietary exposure to chemical contaminants and consumption of unprocessed red meat, processed meat, and legumes. Expo. Health 2024, 16, 1421–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Human Risk Assessment of Multiple Chemicals Using Component-Based Approaches: A Horizontal Perspective (EFSA Supporting Publications, en-1759); EFSA: Parma, Italy; Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/supporting/pub/en-1759 (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Vandenberg, L.N.; Colborn, T.; Hayes, T.B.; Heindel, J.J.; Jacobs, D.R.; Lee, D.-H.; Shioda, T.; Soto, A.M.; vom Saal, F.S.; Welshons, W.V.; et al. Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: Low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses. Endocr. Rev. 2012, 33, 378–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gear, R.B.; Belcher, S.M. Impacts of bisphenol A and ethinyl estradiol on male and female CD-1 mouse spleen. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Merrill, M.A.; Vandenberg, L.N.; Smith, M.T.; Goodson, W.; Browne, P.; Patisaul, H.B.; Guyton, K.Z.; Kortenkamp, A.; Cogliano, V.J.; Woodruf, T.J.; et al. Consensus on the key characteristics of endocrine-disrupting chemicals as a basis for hazard identification. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; United Nations Environment Programme. State of the Science of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals—2012 (Summary for Decision-Makers); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/78102/WHO_HSE_PHE_IHE_2013.1_eng.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- US EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs) in Water; EPA Office of Water: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Gürmeriç, H.E.; Basaran, B. Microplastics in Dairy Products: Occurrence, Characterization, Contamination Sources, Detection Methods, and Future Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçifçi, Z.; Dizman, S.; Basaran, B.; Aliu, H.; Akçay, H.T. Occurrence and evaluation of microplastics in honeys: Dietary intake and risk assessment. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 145, 107831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavali Gilani, P.; Moradian, M.H.; Tajdar-oranj, B.; Basaran, B.; Peivasteh-roudsari, L.; Javanmardi, F.; Khodaei, S.M.; Alizadeh, A.M. Microplastics comprehensive review: Impact on honey bee, occurrence in honey and health risk evaluation. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 62, 1772–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, B.; Aytan, Ü.; Şentürk, Y. First occurrence and risk assessment of microplastics in enteral nutrition formulas. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 191, 114879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, B.; Özçifçi, Z.; Kanbur, E.D.; Akçay, H.T.; Gül, S.; Bektaş, Y.; Aytan, Ü. Microplastics in honey from Türkiye: Occurrence, characteristic, human exposure, and risk assessment. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 135, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, B.; Aytan, Ü.; Şentürk, Y.; Özçifçi, Z.; Akçay, H.T. Microplastic contamination in some beverages marketed in türkiye: Characteristics, dietary exposure and risk assessment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 189, 114730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, J. Assessment of microplastics in human stool: A pilot study. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 934, 172021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, M.; Zhao, R.; Xu, Y. Microplastics in the human body: A comprehensive review of recent advances and implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 171552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elnabi, M.K.; Elkaliny, N.E.; Elyazied, M.M.; Azab, S.H.; Elkhalifa, S.A.; Elmasry, S.; Mouhamed, S.M.; Shalamesh, M.E.; Alhorieny, A.N.; Abd Elaty, E.A.; et al. Toxicity of heavy metals and recent advances in their removal: A review. Toxics 2023, 11, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dueñas-Moreno, J.; Mora, A.; Kumar, M.; Meng, X.Z.; Mahlknecht, J. Worldwide risk assessment of phthalates and bisphenol A in humans: The need for updating guidelines. Environ. Int. 2023, 181, 108294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Scientific Committee; More, S.; Bampidis, V.; Benford, D.; Bragard, C.; Halldorsson, T.; Hernández-Jerez, A.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Koutsoumanis, K.; Lambré, C.; et al. Guidance on risk assessment of nanomaterials to be applied in the food and feed chain: Human and animal health. EFSA J. 2021, 19, 6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Scientific Committee. Guidance on technical requirements for regulated food and feed product applications to establish the presence of small particles including nanoparticles. EFSA J. 2021, 19, 6769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Abbreviation/ Concept | Definition and Importance |

|---|---|

| NOAEL (No-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level) | The highest experimental dose level at which no adverse effects are observed. It is determined in animal studies and is generally used as the Point of Departure (PoD) in risk assessment. The NOAEL serves as a reference point for establishing safe intake levels for humans [17]. |

| LOAEL (Lowest-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level) | The lowest experimental dose at which an adverse effect is first observed, indicated by a statistically significant change. In the absence of a NOAEL in a study, the LOAEL value can serve as a Point of Departure (PoD); however, the application of additional uncertainty factors is necessary in this context [17]. |

| ADI (Acceptable Daily Intake)/TDI (Tolerable Daily Intake) | The amount of a substance that, based on current knowledge, is considered to pose no appreciable health risk when consumed daily over a lifetime (usually expressed in milligrams per kilogram of body weight). The calculation is typically performed by dividing the NOAEL or BMDL from animal studies by relevant safety (uncertainty) factors. The term ADI refers to substances intentionally added into foods, including food additives, pesticide residues, and veterinary drug residues, whereas TDI is typically used for substances that occur unintentionally, such as industrial contaminants [17]. |

| ARfDs (Acute Reference Dose) | The maximum dose considered acceptable for health after acute exposure (less than 24 h). It is generally assessed for substances with potential acute toxicity, as exemplified by pesticides. If the intake of an individual remains below this threshold during a single meal or day, it is considered that there is no risk of acute poisoning. ARfD value is expressed in mg/kg and is derived from acute toxicity studies [17]. |

| BMD/BMDL (Benchmark Dose/Lower Confidence Limit) | The BMD is derived from statistical modeling of the experimental dose–response curve and is typically defined as the dose expected to result in a 10% incidence of an adverse effect within the population (e.g., tumor formation). The Benchmark Dose Lower Confidence Limit (BMDL) denotes the lower confidence limit, generally set at 95%, for this dosage. The BMD approach serves as an alternative to the NOAEL method, especially in studies characterized by strong dose–response data. The BMDL value can serve as a Point of Departure (PoD) and be divided by appropriate safety factors. In contemporary risk assessment, the BMD method is favored over the NOAEL as it more accurately accounts for experimental uncertainty and employs the complete dataset [17]. |

| MOE (Margin of Exposure) | The Margin of Exposure (MOE) is a ratio used specifically in the risk characterization of genotoxic and carcinogenic substances. The calculation involves comparing an experimentally derived reference dose, typically the BMDL or LOAEL from animal studies, with the actual human exposure. A higher MOE value indicates a reduced risk linked to the existing level of exposure to that substance. For genotoxic carcinogens, EFSA has established a practical guidance criterion: an MOE value of 10,000 or higher, calculated from the BMDL10 derived from animal data, signifies a low level of concern for public health. The MOE functions as a quantitative measure, offering risk managers insight into the potential need for additional action [17,20]. |

| TTC (Threshold of Toxicological Concern) | The TTC is a preliminary screening concept designed for numerous substances lacking adequate toxicological data. Daily intake levels regarded as unlikely to cause harm have been established for particular groups of chemical structures based on current knowledge. The TTC value for a structurally simple organic compound considered inert may be 1.5 µg/kg body weight per day. If actual exposure is below this threshold, it can be concluded that comprehensive toxicity testing and risk assessment for that substance are unnecessary. The TTC approach was established as a practical method for prioritizing substances from a vast array of compounds, including flavoring agents and migration products. Of course, the TTC does not constitute a definitive assurance of safety; instead, it reflects an assumption of a negligible risk threshold. Exceeding the TTC value necessitates further toxicological assessment [17]. |

| Contaminants/ Main Food Sources | Sources of Contamination | Potential Health Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Pesticides: Fruits, vegetables, cereal grain products, and other pesticide-treated agricultural products | Pesticide contamination in foods mainly results from the use of insecticides, herbicides, and fungicides in agricultural production. These chemicals can reach foods through leaves, fruits, soil, or water, and may also enter the food chain via polluted irrigation water, residual soil contamination, or treatments applied during storage and transport. In animal-derived foods, residues generally occur indirectly through contaminated feed [56,57,58,59]. | The health effects of pesticides vary depending on the specific compound, exposure duration, and individual susceptibility. Acute exposure may cause nausea, vomiting, dizziness, respiratory distress, skin or eye irritation, neurological symptoms, and, in severe cases, organ failure [60,61]. Chronic low-dose exposure is linked to impaired immune function, endocrine disruption, neurological and reproductive problems, and fetal developmental effects [62,63,64,65,66]. Certain pesticide classes, including organophosphates and carbamates, have also been identified by international agencies as potential or probable human carcinogens [19]. |

| Potentially toxic metals: Cereal grains and grain products, fruits and vegetables, seafoods, particularly large fish species and shellfish, milk and dairy products, meat and meat products, and other foods contaminated with potentially toxic metals | Contamination sources of potentially toxic metals in food primarily arise from environmental and technological processes. The application of fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation water in agriculture can result in the migration of metals into soil and subsequently into plant-based foods. Industrial activities and environmental pollution lead to the accumulation of mercury and arsenic, especially in seafood, whereas feed and water contamination serve as significant sources in animal-derived foods. Moreover, the processing, storage, and packaging stages can facilitate the migration of metals, including aluminum and lead, into food products [67,68,69,70]. | Potentially toxic metals accumulate in the body due to their non-biodegradable nature and can adversely affect multiple organs. Lead and mercury primarily damage the central nervous system and are associated with learning difficulties, cognitive impairment, and behavioral disorders in children [71,72,73]. Cadmium can reduce bone mineral density and cause irreversible kidney damage [74,75]. Arsenic exposure is linked to skin lesions, cardiovascular problems, hepatotoxicity, and several cancers, including skin, lung, and bladder cancer [76,77]. Long-term aluminum exposure has been associated with neurodegenerative disorders, particularly Alzheimer’s disease [78,79]. Chromium may impair kidney function, while cobalt and nickel can trigger immune reactions and respiratory irritation [80,81,82]. These effects vary depending on age, physiological status, and exposure duration, with children, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals being the most vulnerable. |

| Mycotoxins: Cereal grains and grain products (corn, wheat, barley, rice), legumes and oilseeds (peanut, hazelnut, walnut, soy), dried fruits (dried fig, apricot, raisins), spices (red pepper, black pepper), coffee and coffee products, milk and dairy products, and other foods contaminated with mycotoxins. | Mycotoxin contamination arises from both primary sources, such as the field, and secondary sources, including post-harvest, storage, and processing stages. Primary contamination takes place during the crop growth period in the field, influenced by factors including high humidity, temperature variations, insect damage, and inadequate agricultural practices, which facilitate the proliferation of molds such as Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Penicillium. Secondary contamination occurs post-harvest due to insufficient drying, inadequate ventilation, humid and warm storage conditions, as well as during processing and transportation. The occurrence of mycotoxins in food results directly from environmental conditions and practices during production and storage [83,84,85,86]. | Mycotoxins can exert both acute and chronic toxic effects and are well known for their carcinogenic, mutagenic, teratogenic, and immunotoxic properties [87,88]. Aflatoxins—especially aflatoxin B1—are highly hepatotoxic and may cause acute liver failure as well as increase the risk of liver cancer with long-term exposure [89,90]. Ochratoxin A accumulates in the kidneys, leading to nephrotoxicity, impaired renal function, and potential carcinogenicity [91,92]. Fumonisins affect the nervous system and have been associated with congenital abnormalities such as neural tube defects [93,94]. Trichothecenes inhibit protein synthesis, resulting in immune suppression and gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea, vomiting, and bleeding disorders [95,96]. Zearalenone, due to its estrogenic activity, disrupts hormonal balance and may cause reproductive disorders [97,98]. The severity of these effects depends on exposure dose, duration, and individual susceptibility, with children, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals being the most vulnerable. Overall, mycotoxins pose a substantial public health concern, contributing to both non-carcinogenic risks such as nephrotoxicity and immunotoxicity, and carcinogenic risks, particularly hepatocarcinogenesis. |

| Contaminants/ Main Food Sources | Sources of Contamination | Potential Health Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Process contaminants HMF: Honey, fruit juices, dried fruits, coffee, UHT milk, and bread, etc. Acrylamide: French fries, potato chips, coffee, biscuits, crackers, breakfast cereals, and bread, etc. HCAs: Meat, poultry, fish and processed meat products, etc. Chloropropanols: Refined vegetable oils, margarine, frying oils, soy sauce, etc. PAHs: Meat, and fish, as well as roasted coffee, cocoa, nuts, certain vegetable oils, and cereals, etc. | HMF, acrylamide, HCAs, chloropropanols, and PAHs are widely formed in foods during thermal processing, cooking, manufacturing, or storage. HMF appears when sugar-containing foods are exposed to high temperatures or prolonged storage, while acrylamide develops during frying, baking, and roasting via the Maillard reaction. HCAs form in protein-rich foods such as meat and fish cooked at high temperatures. Chloropropanols are generated mainly during the processing of refined vegetable oils, soy sauce, and other fat-based products. PAHs commonly arise through smoking, charring, and roasting methods [116,117,118,119]. | High intakes of HMF may exert cytotoxic effects [120]. Acrylamide is primarily neurotoxic and has been classified by the IARC as probably carcinogenic to humans [19,121]. HCAs are mutagenic, capable of inducing DNA damage, and have been linked to increased risks of colon, pancreatic, and prostate cancers with long-term exposure [122,123,124]. Chloropropanols show nephrotoxic and reproductive toxicity, and some derivatives have been evaluated for their carcinogenic potential [19,125,126]. PAHs possess strong mutagenic and carcinogenic properties, with compounds such as benzo[a]pyrene clearly associated with cancer development in humans [19,127,128]. |

| Food additives Nitrite and nitrate: processed meat products (e.g., soudjouk, sausages, salami, hot dogs, and ham), and some vegetables. Potassium sorbate and sodium benzoate: fruit juices, carbonated beverages, pickles, ketchup and other sauces, some canned products, jams, marmalades, and other foods in which they are used. Aspartame: sugar-free chewing gums, sweetener tablets, and other foods containing it. | Nitrite, nitrate, potassium sorbate, sodium benzoate, aspartame, and various other additives are intentionally incorporated into foods, each serving a specific technological function. Food additives are essential for ensuring the safety, stability, and sensory quality of food products [129,130,131]. | High exposure to nitrites and nitrates may increase cancer risk due to the formation of methemoglobinemia and nitrosamines [132,133,134]. Although potassium sorbate is generally considered safe, excessive intake may trigger allergic reactions or gastrointestinal discomfort [135,136]. Sodium benzoate may also cause toxic effects at high levels or when combined with benzoic acid derivatives [137,138]. Aspartame is widely used as a low-calorie sweetener but poses risks for individuals with phenylketonuria and has been linked to headaches and neurological symptoms when consumed in excess [139,140]. Additionally, some colorants and emulsifiers have been associated with further health concerns [141]. |

| Packaging and environmental contaminants PCBs: Fatty fish, milk and dairy products, meat and meat products, other contaminated foods. PCDD/Fs: fish and shellfish, fatty meat products, milk and dairy products, other contaminated foods. PAEs: Milk and dairy products, vegetable oils, processed foods, and other contaminated foods. PFAS: fish, seafood, and other contaminated foods. BPA: canned foods, beverages packaged in plastic bottles, and other processed foods. | PCBs, PCDD/Fs, PAEs, PFAS, and BPA contaminate food mainly via environmental pollution and migration from packaging materials. While PCBs and PCDD/Fs are primarily transferred to animal-derived foods through industrial emissions, combustion processes, and contaminated soil or water; PAEs migrate into food from plastic materials used as plasticizers. PFAS compounds are present in foods as a result of their application in food packaging coatings and their environmental durability. BPA, on the other hand, is a substantial source of contamination, as it transitions from the inner linings of canned foods, plastic bottles, and baby bottles into food and beverages [142,143,144,145,146,147,148]. | PCBs, PCDD/Fs, PAEs, PFAS, and BPA are significant concerns due to their persistence and bioaccumulation. PCBs accumulate in the body and have been linked to immune suppression, neurodevelopmental issues, endocrine disruption, liver damage, and cancer [149,150,151]. PCDD/Fs are highly toxic and associated with skin lesions, immune dysfunction, and reproductive and developmental problems [152,153,154]. PAEs act as endocrine disruptors and may affect reproductive health, sperm quality, hormonal balance, and fetal development, posing particular risks for infants and children [155,156,157]. PFAS compounds bioaccumulate and are associated with thyroid disorders, altered lipid metabolism, elevated liver enzymes, immune suppression, and higher risks of kidney and testicular cancers [158,159,160]. BPA, through its estrogen-mimicking activity, disrupts endocrine function and has been linked to obesity, insulin resistance, infertility, early puberty, cardiovascular disease, and hormone-related cancers [161,162,163]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pekmezci, H.; Sipahi, S.; Başaran, B. Health Risk Assessment of Dietary Chemical Exposures: A Comprehensive Review. Foods 2025, 14, 4133. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234133

Pekmezci H, Sipahi S, Başaran B. Health Risk Assessment of Dietary Chemical Exposures: A Comprehensive Review. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4133. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234133

Chicago/Turabian StylePekmezci, Hilal, Simge Sipahi, and Burhan Başaran. 2025. "Health Risk Assessment of Dietary Chemical Exposures: A Comprehensive Review" Foods 14, no. 23: 4133. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234133

APA StylePekmezci, H., Sipahi, S., & Başaran, B. (2025). Health Risk Assessment of Dietary Chemical Exposures: A Comprehensive Review. Foods, 14(23), 4133. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234133