Research on Regional Variations in Potato Price Fluctuations and Inter-Regional Transmission Mechanisms in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data and Model

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Research Methodology

3.2.1. Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition

rn−1(t) − imfn(t) = rn(t)

3.2.2. Vector Autoregressive Model

4. Results and Analysis

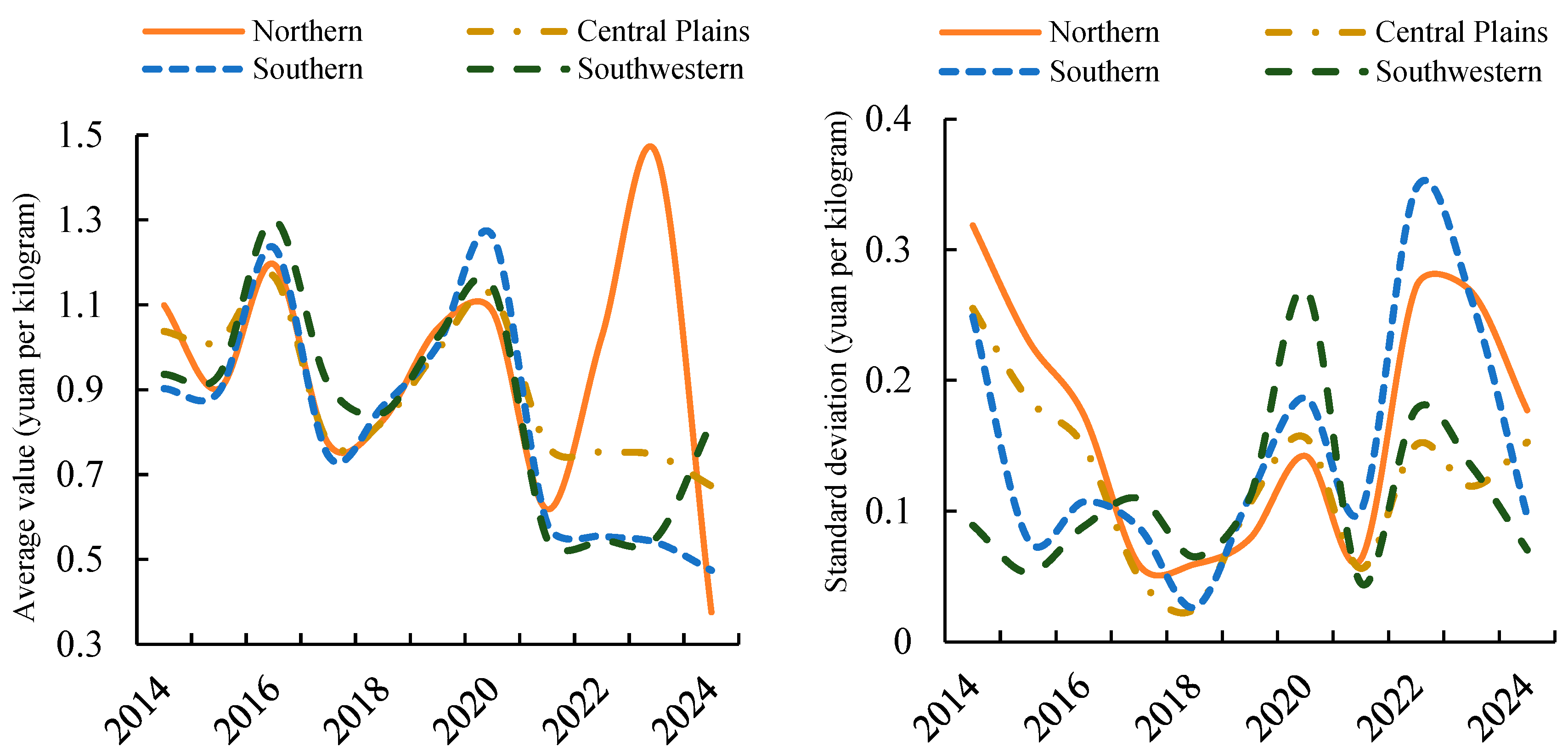

4.1. Analysis of Regional Variations in Potato Price Fluctuations in China

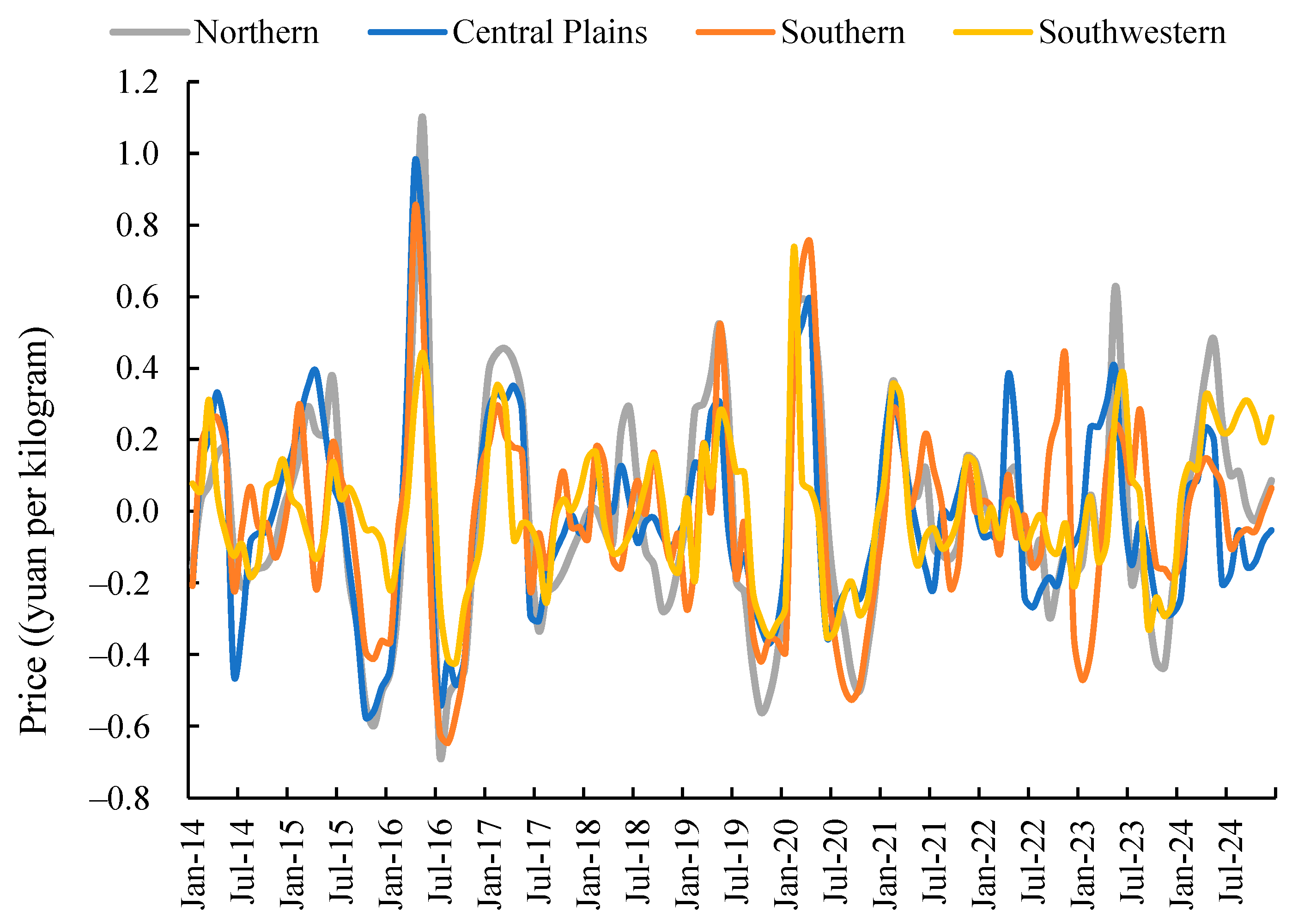

4.1.1. Spatial Variation in High-Frequency Short-Term Fluctuations

| Project | Year | Northern | Central Plains | Southern | Southwestern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variation coefficients /% | 2014 | 13.578 | 22.502 | 15.751 | 13.344 |

| 2015 | 35.785 | 36.164 | 24.437 | 7.361 | |

| 2016 | 54.036 | 49.597 | 50.378 | 28.813 | |

| 2017 | 27.491 | 23.049 | 14.788 | 16.050 | |

| 2018 | 17.174 | 6.983 | 11.458 | 11.559 | |

| 2019 | 39.116 | 23.865 | 30.510 | 22.579 | |

| 2020 | 40.753 | 32.017 | 48.317 | 31.720 | |

| 2021 | 13.874 | 14.346 | 13.538 | 14.967 | |

| 2022 | 12.877 | 19.872 | 19.360 | 6.838 | |

| 2023 | 30.654 | 22.752 | 24.755 | 22.542 | |

| 2024 | 13.833 | 15.598 | 8.663 | 6.758 | |

| Total | 30.494 | 26.691 | 26.766 | 19.580 | |

| Average cycle (months) | 9.429 | 8.000 | 5.739 | 5. 500 | |

| Variance contribution rate (%) | 37.759 | 45.098 | 32.093 | 26.174 | |

| Pearson correlation coefficient | 0.603 ** | 0.676 ** | 0.585 ** | 0.497 ** | |

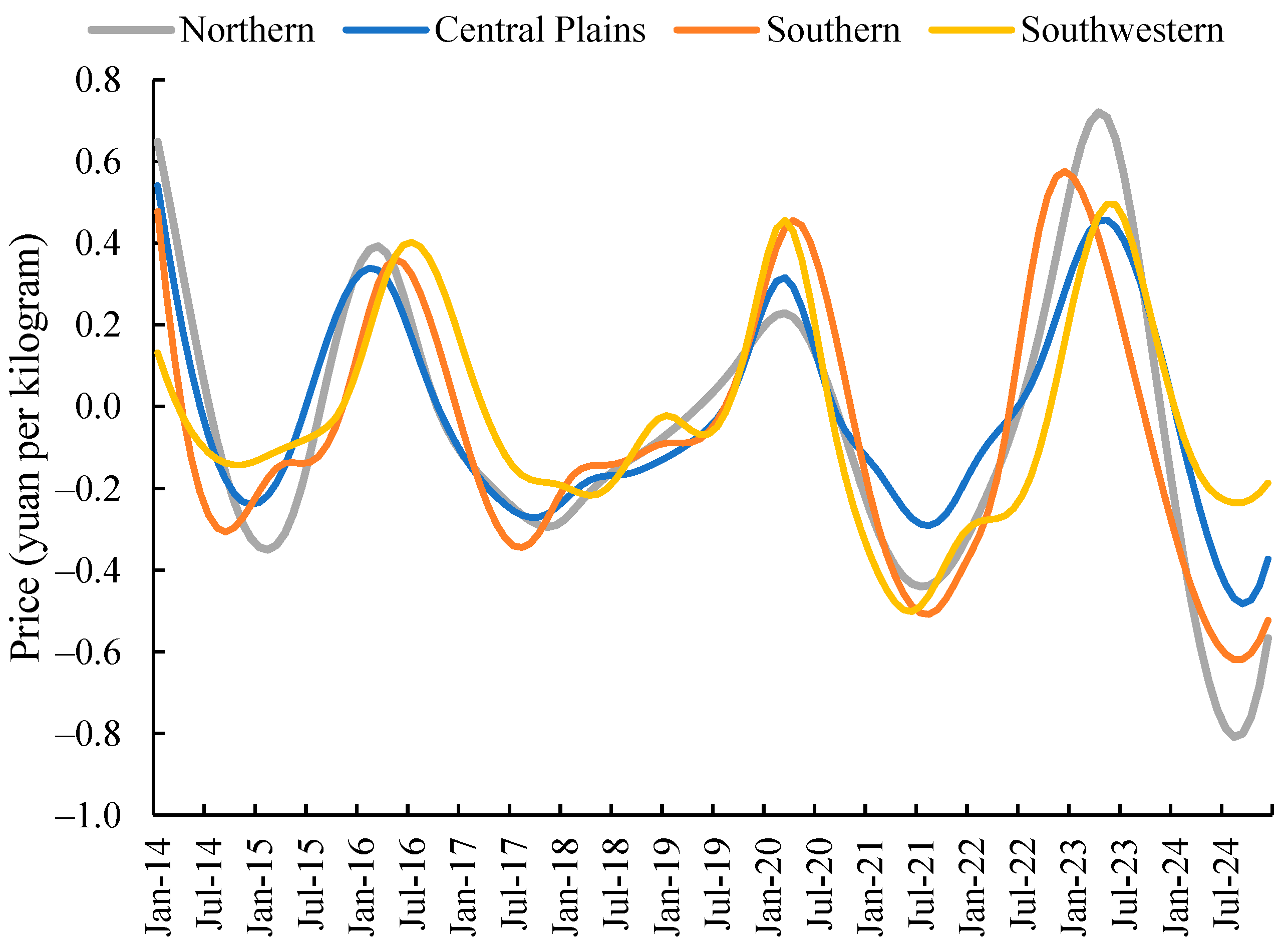

4.1.2. Spatial Variation in Low-Frequency Long-Term Fluctuations

| Project | Year | Northern | Central Plains | Southern | Southwestern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variation coefficients /% | 2014 | 28.981 | 24.597 | 27.556 | 9.509 |

| 2015 | 25.608 | 18.321 | 8.726 | 5.683 | |

| 2016 | 14.525 | 12.845 | 8.658 | 6.790 | |

| 2017 | 7.610 | 6.389 | 11.723 | 12.016 | |

| 2018 | 7.167 | 3.047 | 3.065 | 7.692 | |

| 2019 | 7.583 | 10.667 | 11.102 | 10.818 | |

| 2020 | 13.115 | 13.910 | 14.792 | 23.626 | |

| 2021 | 10.233 | 7.332 | 17.138 | 8.177 | |

| 2022 | 26.511 | 20.014 | 62.480 | 32.689 | |

| 2023 | 18.394 | 15.971 | 48.420 | 24.308 | |

| 2024 | 47.097 | 22.687 | 20.173 | 8.534 | |

| Total | 35.517 | 24.156 | 32.688 | 25.351 | |

| Average cycle (months) | 29.333 | 29.333 | 33.000 | 26.400 | |

| Variance contribution rate (%) | 47.303 | 36.601 | 43.721 | 40.940 | |

| Pearson correlation coefficient | 0.597 ** | 0.588 ** | 0.584 ** | 0.563 ** | |

4.2. Analysis of the Spatial Price Transmission Mechanism for Potatoes in China

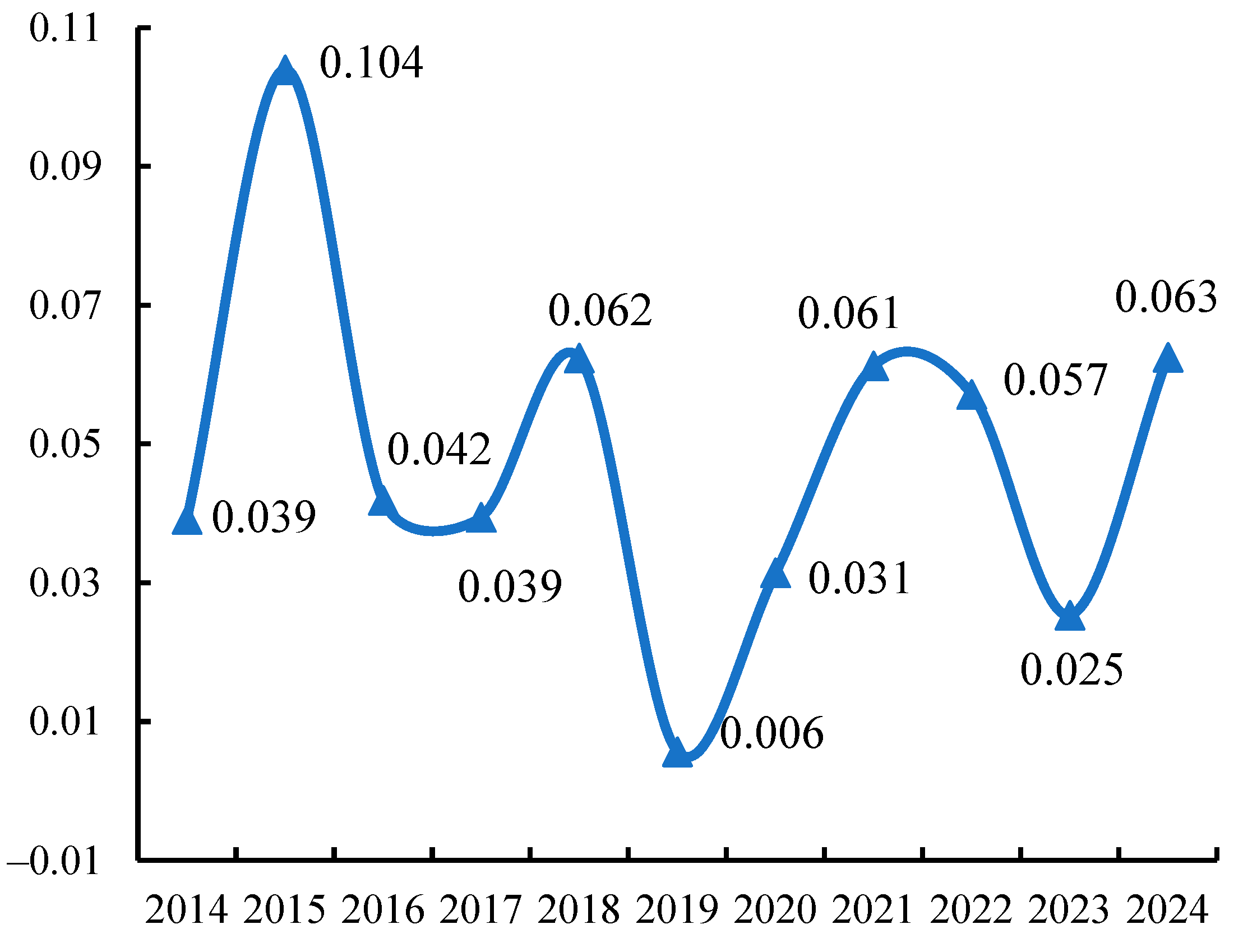

4.2.1. Analysis of Spatial Correlation Across Provincial Regions

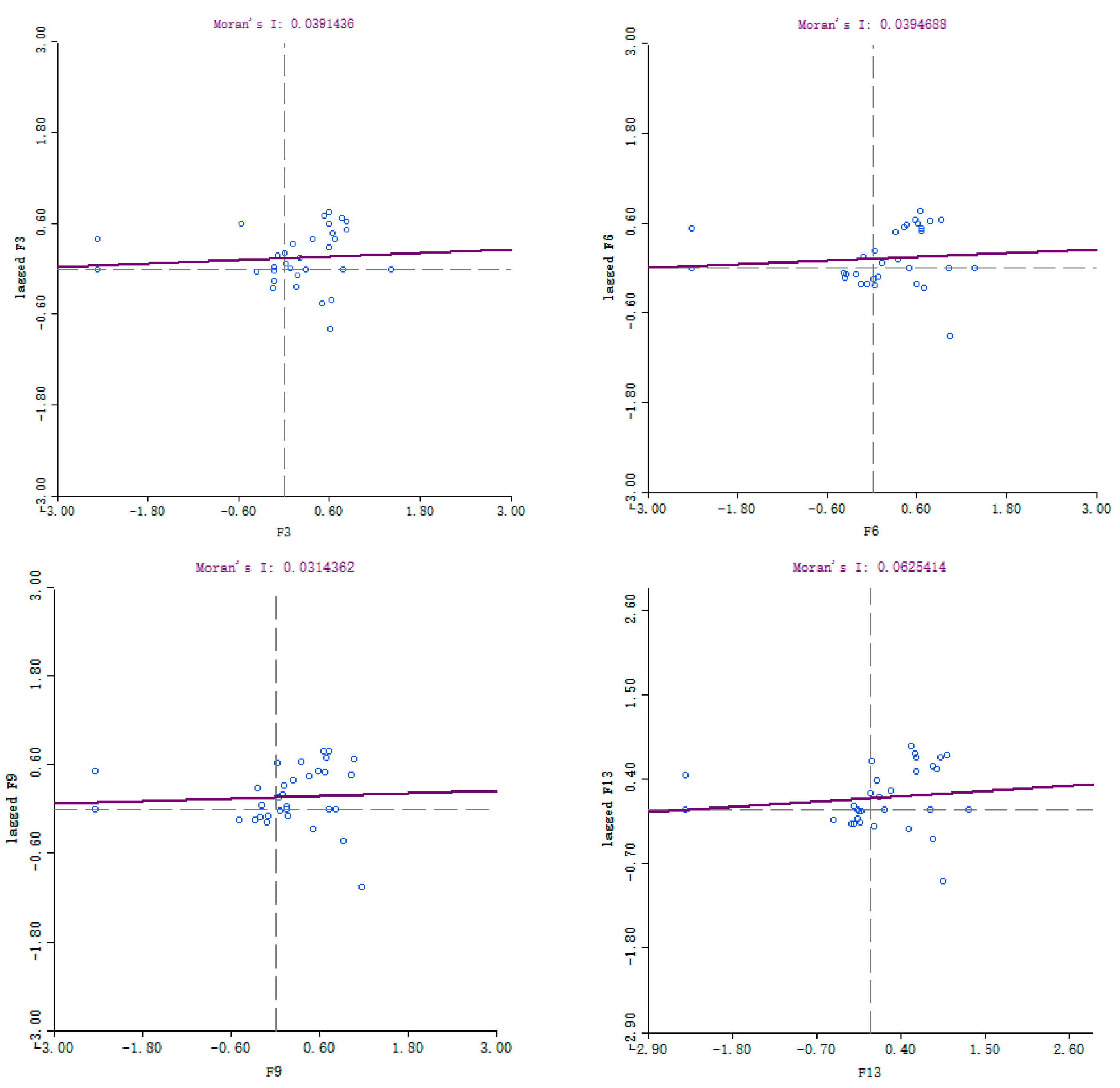

Global Autocorrelation Analysis

Local Autocorrelation Analysis

4.2.2. Interregional Transmission Analysis

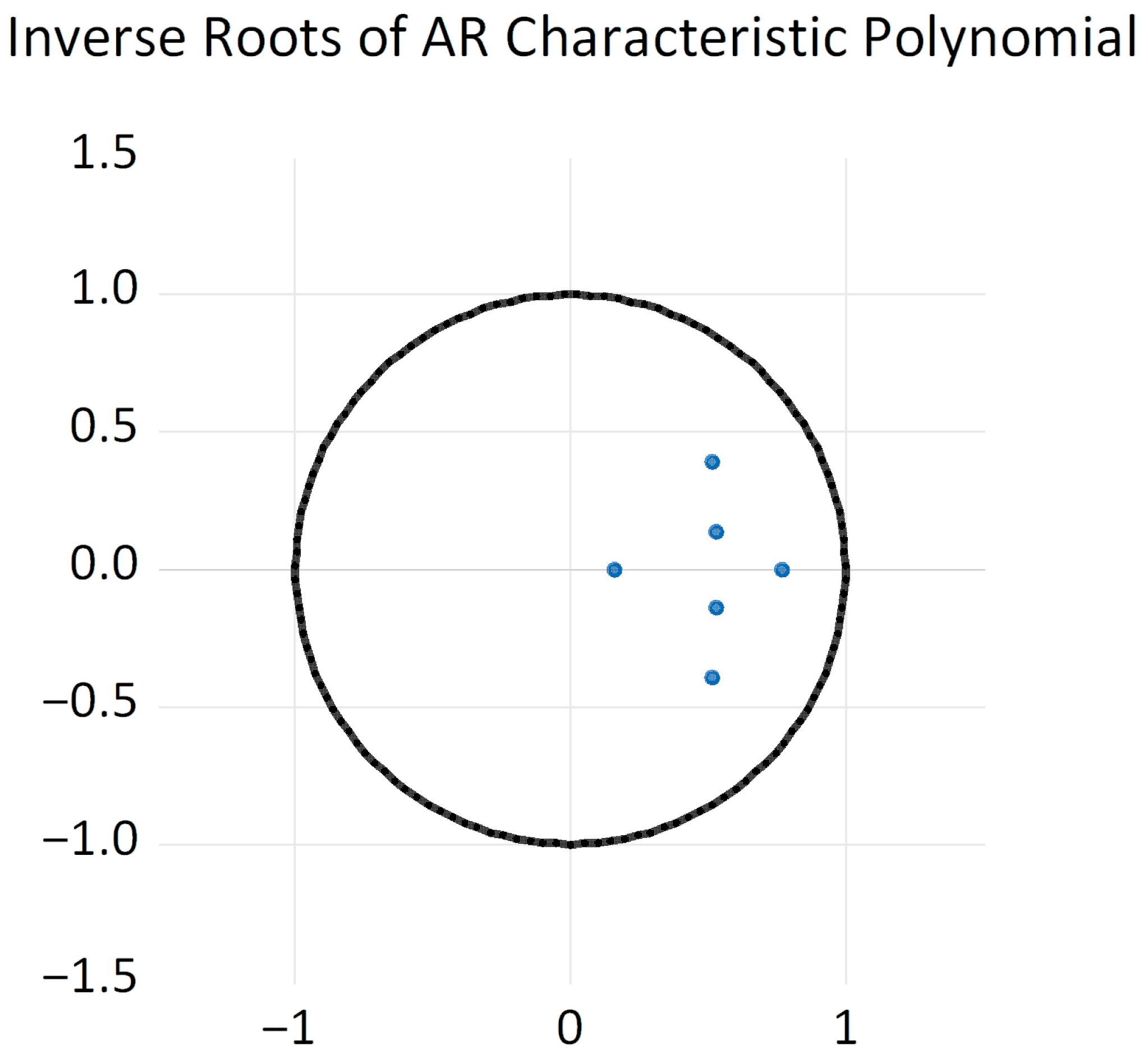

Stability Test

Determination of Lag Order

Stability Test of Equations

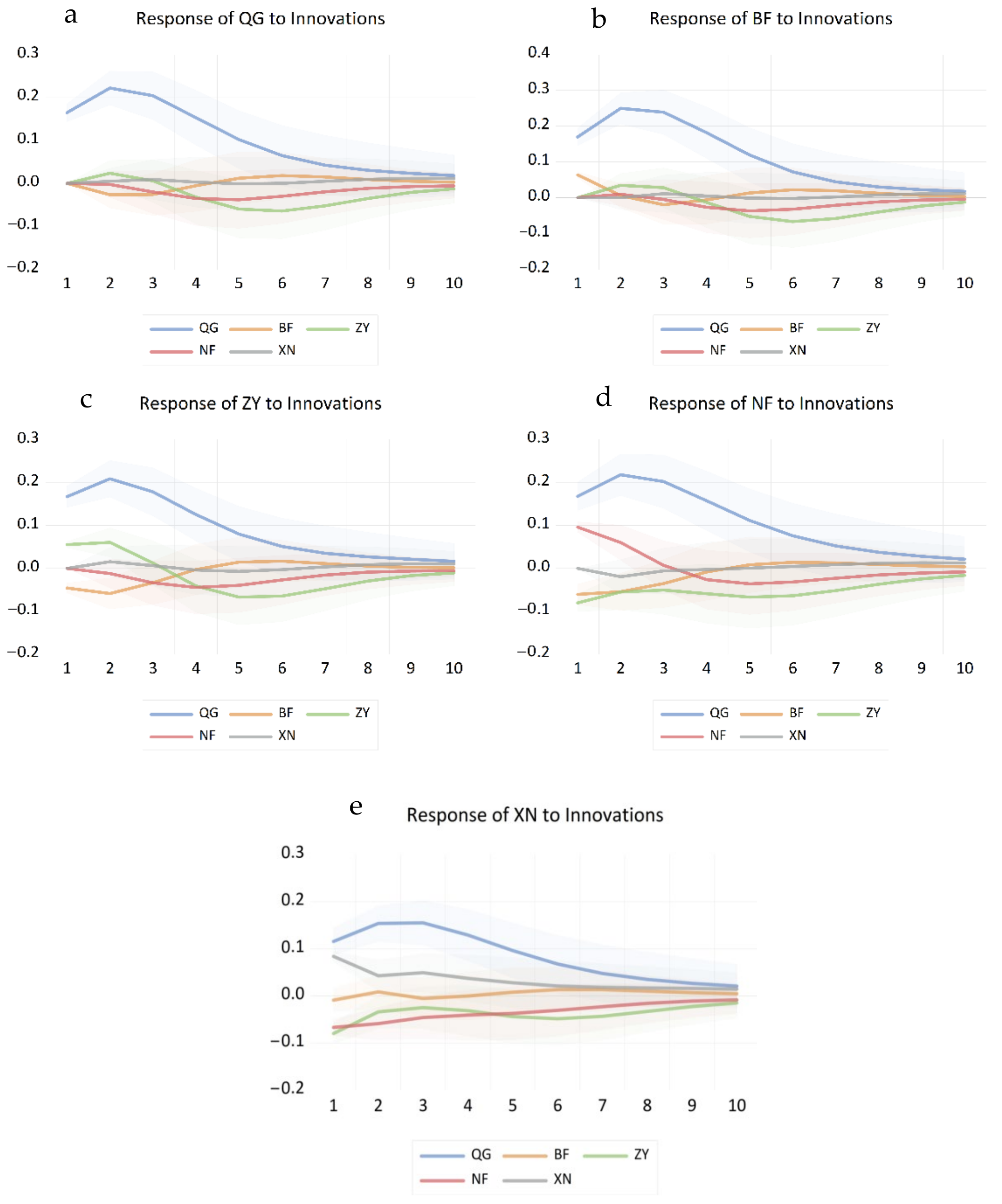

Impulse Response Analysis

Variance Decomposition

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, L.; Mu, T.-H.; Ma, M.-M.; Zhang, R.-F.; Sun, Q.-H.; Xu, Y.-W. Nutritional evaluation of different cultivars of potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) from China by grey relational analysis(GRA) and its application in potato steamed bread making. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.D. The Introduction, Spread, and Impact of American Crops on China’s Food Production. World Agric. 1979, 34–41. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=dSUnQCB_TmONPk4hgQFAsR5skxJlKFawIzeR74gYjbW4ZwHvO3Bhpuysr0UBNsNewWalNEoFrUKXBozJfUUCsOXlMKCOI-qRw45Ci-9wsN5kOhQ071-kDsP071Hrp1oe86dPgw7daDKvdbz4Q26xJVq5hfg3d14PWaUOVWeArw_mQNkHHbJrqw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS%WCNKI (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Gao, M.J.; Lu, H.W.; Li, T.T.; Bo, Q.Q.; Luo, Q.Y. Analysis of Factors Influencing Potato Yield Fluctuations in China Based on VAR Model. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2021, 40, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dawe, D.; Timmer, C.P. Why stable food prices are a good thing: Lessons from stabilizing rice prices in Asia. Glob. Food Secur. 2012, 1, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, R.; Self, S. Staple food price instability and structural change: Indonesian experience. J. Asian Econ. 2016, 47, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Ito, S.; Isoda, H.; Saito, H. A Study on Price Fluctuation in Chinese Grain Markets: Based on ARCH-type Models. Agric. Mark. J. Jpn. 2013, 22, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gouel, C. Optimal food price stabilisation policy. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2013, 57, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, T.; Gil, J.M. Price volatility in food markets: Can stock building mitigate price fluctuations? Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2013, 40, 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M.F. Rising Food Prices, Food Price Volatility, and Social Unrest. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2015, 97, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, D. Rethinking the global food crisis: The role of trade shocks. Food Policy 2011, 36, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Li, T.; Lv, J.; Wang, A.; Luo, Q.; Gao, M.; Li, G. The Fluctuation Characteristics and Periodic Patterns of Potato Prices in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamulczuk, M.; Makarchuk, O.; Sica, E. Searching for market integration: Evidence from Ukrainian and European Union rapeseed markets. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenthal, G. Adam Smith’s analytic-synthetic method and the ‘system of natural liberty’. Hist. Eur. Ideas 2012, 2, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L. Similarities and Differences Between Contemporary Economic Growth Theory and Classical School Growth Theory. Zhongzhou Acad. J. 1991, 16–20. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=dSUnQCB_TmPYQybsRbXyCiMHTqFy45Ze5lr8VEqfq3jOppRuURMXIBcIVxB6649SYdAeDilPir2egQC88kSnGAdsGriHbE19F4xCcE-pghBvXUvLVPoHLCgLi7M7Y76CcDoL8WKeUC6irKdcpIyge1bO3ggYhON5e2i05QqrFS9U0v7aUcvnKA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS%WCNKI (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Westerhoff, F.; Reitz, S. Commodity price dynamics and the nonlinear market impact of technical traders: Empirical evidence for the US corn market. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2004, 349, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrangi, B.; Chatrath, A. Non-linear dynamics in futures prices: Evidence from the coffee, sugar and cocoa exchange. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2003, 13, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.D. The Economics of Grain Price Volatility. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2011, 33, 32–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezitis, A.N.; Stavropoulos, K.S. Price Transmission and Volatility in the Greek Broiler Sector: A Threshold Cointegration Analysis. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2011, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krusec, D. The ‘price puzzle’ in the monetary transmission VARs with long-run restrictions. Econ. Lett. 2010, 106, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C.L. How to Understand High Food Prices. J. Agric. Econ. 2010, 61, 398–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Fletcher, S.M.; Carley, D.H. Peanut price transmission asymmetry in peanut butter. Agribusiness 1995, 11, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.J.; Hayenga, M.L. Price Cycles and Asymmetric Price Transmission in the U.S. Pork Market. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2001, 83, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graubner, M.; Koller, I.; Salhofer, K.; Balmann, A. Cooperative versus non-cooperative spatial competition for milk. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2011, 38, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.; Marhold, K. Determinants of household energy use and fuel switching behavior in Nepal. Energy 2019, 169, 1132–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, M.; Rude, J.; Qiu, F. Price Volatility Spillovers in the Western Canadian Feed Barley, US Corn, and Alberta Cattle Markets. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Rev. Can. D’agroecon. 2018, 66, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N.; Rezitis, A. Mean spillover effects in agricultural prices: The case of Greece. Agribusiness 2003, 19, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buguk, C.; Hudson, D.; Hanson, T. Price Volatility Spillover in Agricultural Markets: An Examination of U.S. Catfish Markets. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2003, 28, 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, G.G.; Ciner, C. International transmission on information in corn futures markets. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 1997, 7, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamao, Y.; Masulis, R.W.; Ng, V. Correlations in Price Changes and Volatility across International Stock Markets. Rev. Financ. Stud. 1990, 3, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, M.E.; Pace, R.D.; Tomas, M.J., III. Complements or substitutes? Equivalent futures contract markets—The case of corn and soybean futures on U.S. and Japanese exchanges. J. Futures Mark. Futures Options Other Deriv. Prod. 2002, 22, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rivera, G.; Helfand, S.M. The Extent, Pattern, and Degree of Market Integration: A Multivariate Approach for the Brazilian Rice Market. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2001, 83, 576–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanidze, M.; Götz, L. Determinants of spatial market efficiency of grain markets in Russia. Food Policy 2019, 89, 101769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljkovic, D. US and Canadian livestock prices: Market integration and trade dependence. Appl. Econ. 2009, 41, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Kou, Y. Spatiotemporal Differences and Influencing Factors of Pork Price Cycle Fluctuations. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2021, 37, 445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, X.; Qi, C.J. Fruit Price Fluctuations, Product Substitutability, and North-South Spatial Differences. J. Agric. For. Econ. Manag. 2022, 21, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Nie, Y.B.; Li, B.L. Spatial Effects of Mutton Price Changes in China. J. China Agric. Univ. 2019, 24, 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.Y.; Xiao, H.F. Price Transmission in the Mutton Sheep Industry Chain in China. J. China Agric. Univ. 2021, 26, 245–256. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.Y.; Liu, F.; Liu, Y.Z. An Empirical Study on Pork Price Fluctuations in China Based on VAR Model. Chin. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 56, 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.F.; Liu, N.N. Horizontal Transmission Relationships of Major Meat Prices in China: An Empirical Analysis Based on DAG-SVAR Model. Agric. Outlook 2022, 18, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.X.; Zhang, X.C. The Impact of External Shocks on China’s Agricultural Product Price Fluctuations: From the Perspective of Agricultural Industry Chain. Manag. World 2011, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.L.; Yuan, D.Y.; Teng, J.M. Price Network Linkage and Spillover Effects Among Hog Markets in Central China: Based on an Asymmetric Time-Varying Perspective. Res. Agric. Mod. 2024, 45, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.P. Research on the Integration Degree of Wheat, Corn, and Hog Purchase Markets in China. China Rural. Surv. 1999, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, Z.P.; Fang, G.Z.; Qi, C.J. Spatial Correlation Effects of Citrus Prices in Main Producing Areas: Based on VAR Model and Social Network Analysis. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2023, 44, 174–183. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Xu, K. Price Transmission Mechanism in the Production and Marketing of Edible Fungi: Taking Enoki Mushroom, Oyster Mushroom, and Shiitake Mushroom in Beijing and Hebei as Examples. J. Yunnan Agric. Univ. 2022, 16, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Jiang, Y.X.; Zhang, B.Z. Price Linkage of Agricultural Products Between China and “Belt and Road” Countries: Also on the Impact of Sino-US Trade Friction. Issues Agric. Econ. 2021, 126–144. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.13246/j.cnki.iae.2021.03.011 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Liu, L.; Sun, W.L.; Wang, G.G. The Impact of International Grain Price Fluctuations on China’s Agricultural Product Market Under High-Level Opening-Up. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2022, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, Q.Y. Study on the Price Volatility of Potato Wholesale Market in China. China Veg. 2011, 7, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, J.K.; Zhang, D.L. Analysis of Potato Price Fluctuations in China Based on X12 Seasonal Adjustment Model. Rural Econ. Sci.-Technol. 2018, 29, 166–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lun, R.Q.; Luo, Q.Y.; Gao, M.J.; Yang, Y.D. Analysis of Potato Wholesale Market Price Fluctuations in China. Agric. Outlook 2020, 16, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Yan, S.Q. Analysis of Potato Wholesale Market Price Fluctuations in Gansu Province. Chin. Potato 2022, 36, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M.J.; Zhang, M.; Luo, Q.Y. Spatiotemporal Differences of Potato Price Fluctuations in China. Price Theory Pract. 2017, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Li, F.Y. Potato Price Prediction Based on BP Neural Network. Value Eng. 2020, 39, 201–203. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Gao, M.J.; Luo, Q.Y. Quantitative Analysis of Potato Price Fluctuations in China. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2020, 41, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T.Y.; Xu, Y.; Ma, G.X.; Wang, Z.Q. Review of Theories and Methods of Regional Economic Spatial Structure. Prog. Geogr. 2009, 28, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Huka, H.; Ruoja, C.; Mchopa, A. Price Fluctuation of Agricultural Products and its Impact on Small Scale Farmers Development: Case Analysis from Kilimanjaro Tanzania. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 6, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.Z. Spatial Linkage of Corn Market in China Under the Background of Price Support Policy Reform. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 2585–2604. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.S.; Ma, J.J.; Shen, C.; Yang, W.; Liu, J.F. Study on the Law of Potato Price Fluctuations in China: An Empirical Analysis Based on X-12 and H-P Filter Methods. China Veg. 2017, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapil, C.; Kumar, J.G.; Ranjan, K.R. Potato price analysis of Delhi market through ensemble empirical mode decomposition. Bhartiya Krishi Anusandhan Patrika 2019, 34, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.F.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.Z. Analysis of Suitable Planting Areas for Potato in China. Sci. Agric. Sin. 1989, 35–44. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=dSUnQCB_TmNL8VmLjPZIuwOi-pDg6JJx5SNRcWCEGeykX__07zlq8eTfzd2uKF9qp5u0HErPvyHajaPRwzpQVsFYil38sWywvxQ-6bgAmnykH0SkqDoW4tenX21flToVAxC_dems5lhNwoLla2BHT1ZLoVIRG9aB-srKIrxy4FPaJ0zdD5PrSA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS%WCNKI (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Huang, N.E.; Shen, Z.; Long, S.R.; Wu, M.C.; Shih, H.H.; Zheng, Q.; Yen, N.-C.; Tung, C.C.; Liu, H.H. The Empirical Mode Decomposition and the Hilbert Spectrum for Nonlinear and Non-Stationary Time Series Analysis. Proc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1998, 454, 903–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Liu, Z. Forecasting the carbon price sequence in the Hubei emissions exchange using a hybrid model based on ensemble empirical mode decomposition. Energy Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 2708–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lai, K.K.; Wang, S.Y. A new approach for crude oil price analysis based on Empirical Mode Decomposition. Energy Econ. 2007, 30, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, T.T.; Meuwissen, M.P.; Gardebroek, C.; Oude Lansink, A.G. Price and Volatility Transmission and Market Power in the German Fresh Pork Supply Chain. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 68, 861–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiane, O.; Shively, G.E. Spatial integration, transport costs, and the response of local prices to policy changes in Ghana. J. Dev. Econ. 1998, 56, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.B.; Li, J.R. Distinguishing between equilibrium and integration in spatial price analysis. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2002, 84, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C. Research on the transmission mechanism and dynamic impact effect of grain prices at home and abroad. Stat. Decis. 2024, 40, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.-s.; Hu, C.-p.; Lü, Z.; Li, M.-q.; Guo, X.-z. African swine fever and meat prices fluctuation: An empirical study in China based on TVP-VAR model. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 2289–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Production Characteristics | Province |

|---|---|---|

| Northern Single-Crop Zone (BF) | Cultivated only once per year, this summer crop is sown in spring and harvested in autumn. Sowing generally occurs between April and early May, with harvesting taking place from September to early October. | Heilongjiang, Jilin, Hebei, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Gansu, Shaanxi, Qinghai, Xinjiang, Beijing |

| Central Plains Double-Crop Zone (ZY) | The district practises spring and autumn cultivation. Spring production involves sowing from late February to early March, with harvesting occurring from May to mid-June; autumn production entails sowing in August, followed by harvesting in November. | Liaoning, Henan, Shandong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, Tianjin, Shanghai |

| Southern Double-Crop Zone (NF) | Make greater use of the fallow winter period following rice harvest for potato cultivation, implementing autumn or winter sowing. For autumn sowing, plant in late October and harvest from late December to early January; for winter sowing, plant in mid-January and harvest in mid-to-late April. | Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Fujian |

| Southwestern Mixed-Crop Zone (XN) | In high-altitude mountainous regions, cultivation typically follows a single-season pattern of spring sowing and autumn harvesting; whereas in low mountains, river valleys or basins, a two-season cultivation system is more common. Given the complex terrain and pronounced vertical climatic variation, potato cultivation in these areas comprises either a single-crop or a double-crop system. | Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, Tibet, Hunan, Hubei, Chongqing |

| Sequences | t-Statistic | Critical Values at Different Levels of Significance | (C, T, K) | Stability Testing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 5% | 10% | ||||

| National | −5.686 | −4.038 | −3.448 | −3.149 | CT3 | Steady |

| Northern | −6.024 | −4.039 | −3.449 | −3.150 | CT3 | Steady |

| Central Plains | −6.177 | −4.038 | −3.448 | −3.149 | CT3 | Steady |

| Southern | −5.004 | −4.038 | −3.448 | −3.149 | CT3 | Steady |

| Southwest | −3.578 | −4.037 | −3.448 | −3.149 | CT3 | Steady |

| Lag | LR | FPE | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | NA | 1.19 × 10−9 | −6.358048 |

| 1 | 421.4771 | 4.10 × 10−11 | −9.727789 |

| 2 | 61.36510 * | 3.53 × 10−11 * | −9.879354 * |

| 3 | 33.30259 | 3.92 × 10−11 | −9.781732 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, H.; Li, T.; Hao, R.; Liu, Z.; Gao, M.; Chen, J. Research on Regional Variations in Potato Price Fluctuations and Inter-Regional Transmission Mechanisms in China. Foods 2025, 14, 4135. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234135

Lu H, Li T, Hao R, Liu Z, Gao M, Chen J. Research on Regional Variations in Potato Price Fluctuations and Inter-Regional Transmission Mechanisms in China. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4135. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234135

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Hongwei, Tingting Li, Ruoshi Hao, Zixuan Liu, Mingjie Gao, and Junhong Chen. 2025. "Research on Regional Variations in Potato Price Fluctuations and Inter-Regional Transmission Mechanisms in China" Foods 14, no. 23: 4135. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234135

APA StyleLu, H., Li, T., Hao, R., Liu, Z., Gao, M., & Chen, J. (2025). Research on Regional Variations in Potato Price Fluctuations and Inter-Regional Transmission Mechanisms in China. Foods, 14(23), 4135. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234135