Fermentation Process Evaluation of a Sustainable and Innovative Miso Made from Alternative Legumes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganisms and Culture Conditions

2.2. Koji Production

2.3. Legumes Used for Miso Production

2.4. Miso Production

2.5. Microbiological Analysis

2.6. Determination of pH and Total Soluble Solids (TSS)

2.7. Soluble Protein Content

2.8. Soluble Phenolic Compounds

2.9. Reducing Sugars and Organic Acids by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Viability of Yeasts and Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB)

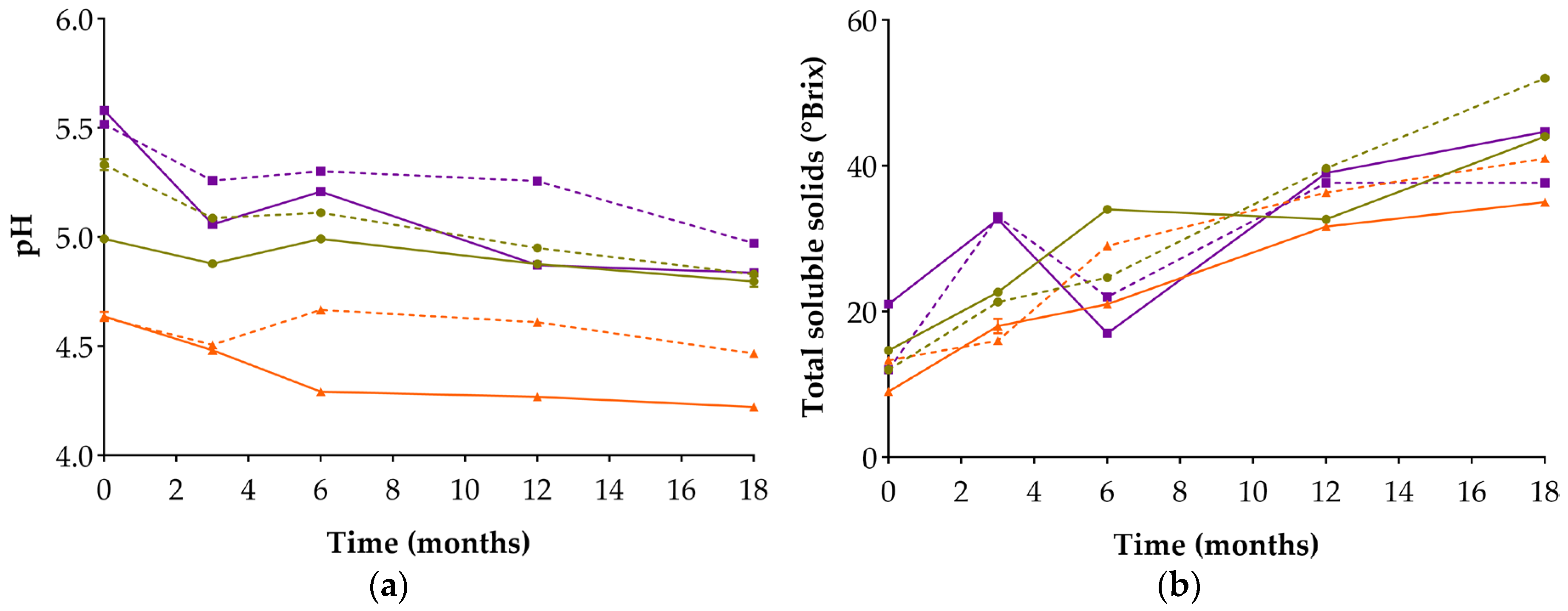

3.2. Evaluation of pH and Total Soluble Solids (TSS)

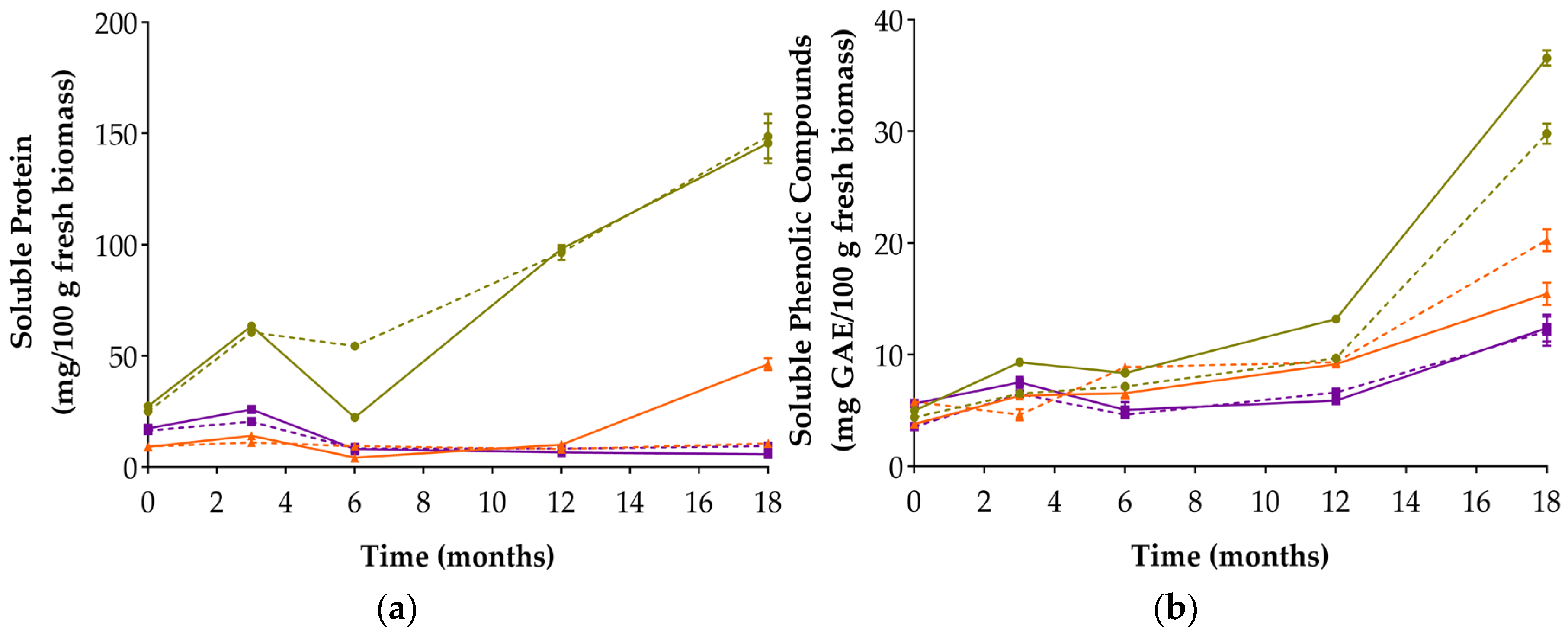

3.3. Soluble Protein and Soluble Phenolic Content

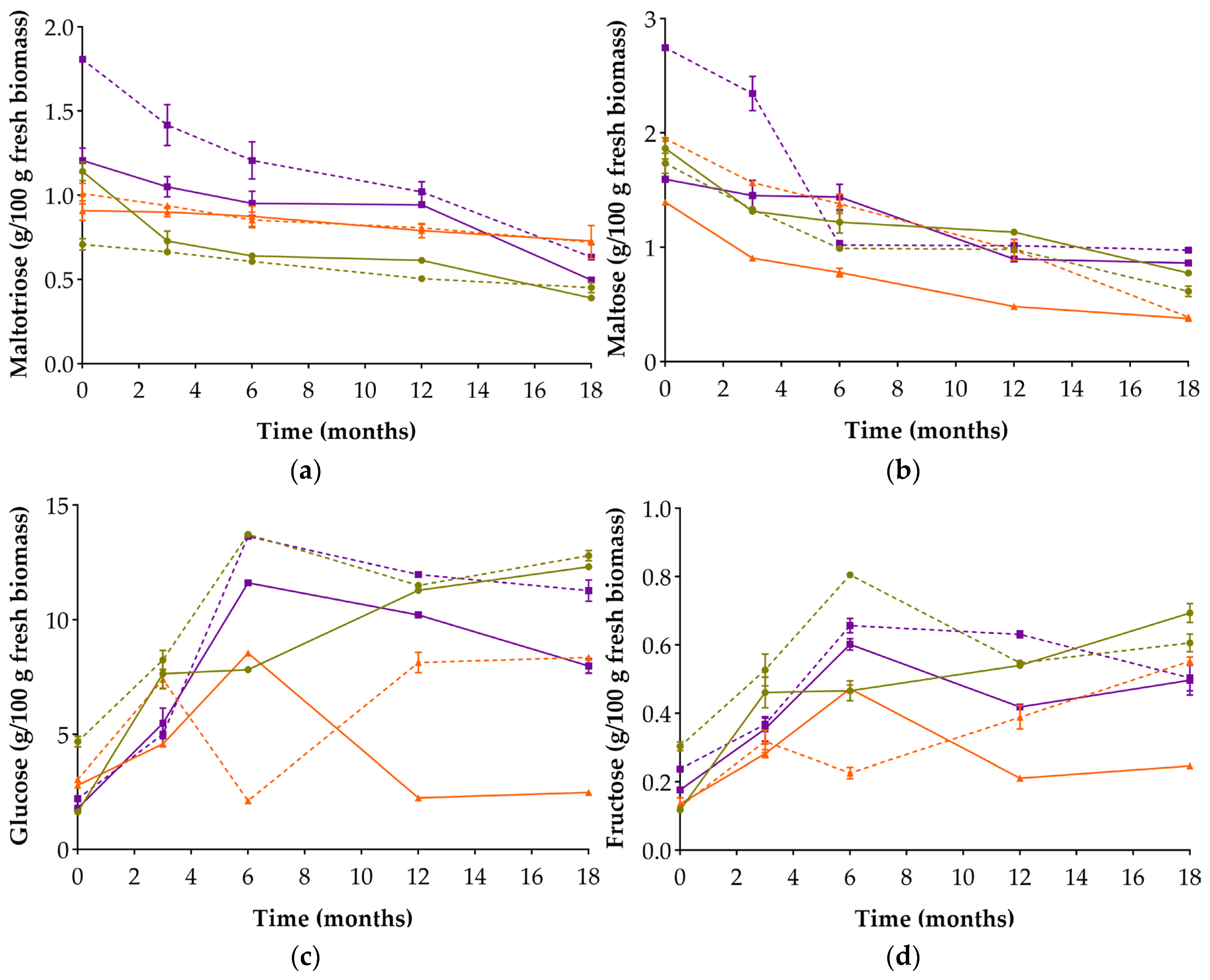

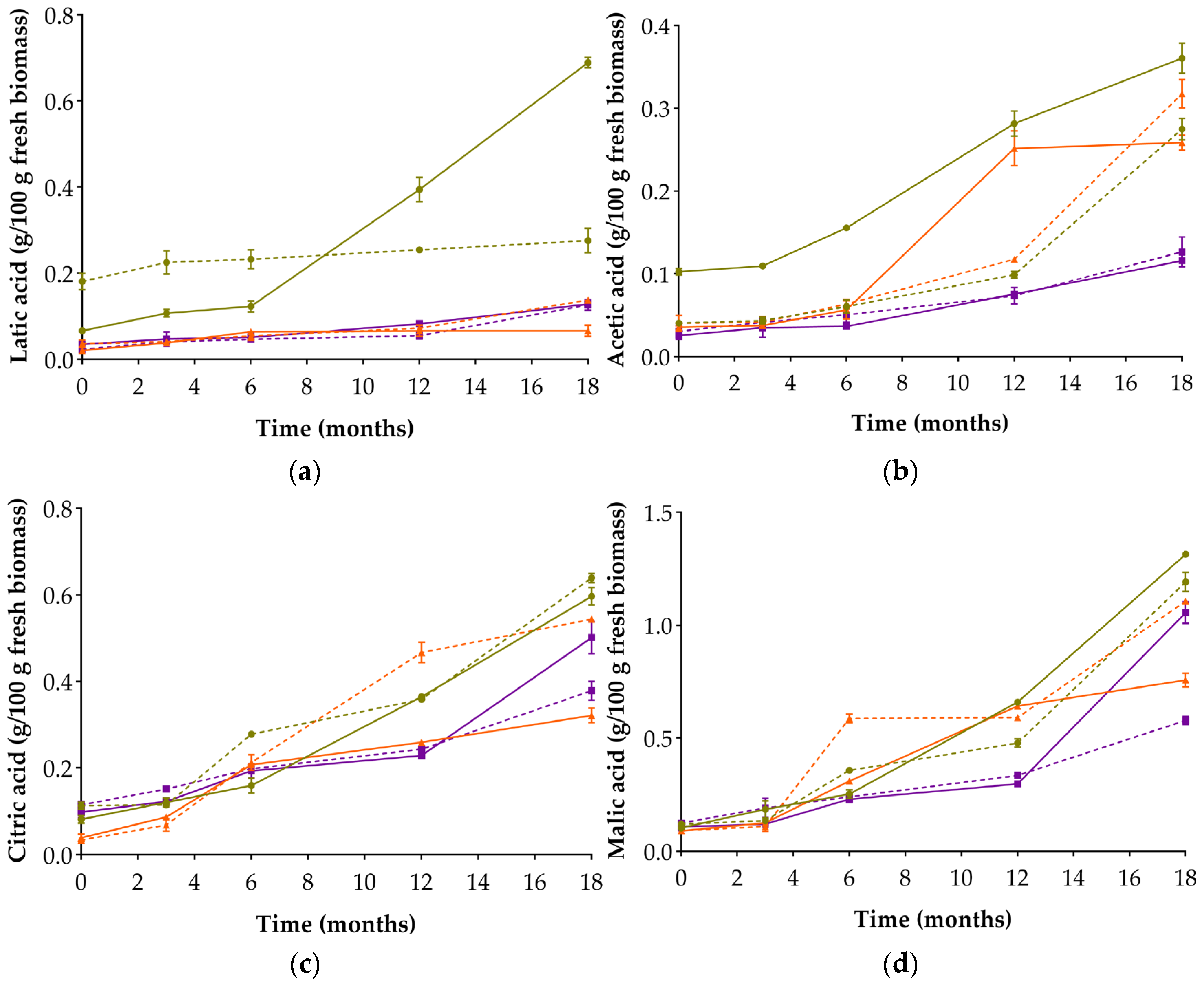

3.4. Reducing Sugars and Organic Acids Evolution

3.5. Soybean-Based Misos

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ilango, S.; Antony, U. Probiotic Microorganisms from Non-Dairy Traditional Fermented Foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 617–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J.G.; Wakeling, L.T.; Bean, D.C. Fermentation and the Microbial Community of Japanese Koji and Miso: A Review. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 2194–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, F.; Afzaal, M.; Abbas, Y.S.; Khan, M.H.; Hussain, M.; Ikram, A.; Ateeq, H.; Noman, M.; Saewan, S.A.; Khashroum, A.O. Miso: A Traditional Nutritious & Health—endorsing Fermented Product. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 4103–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Kishi, T.; Ishida, M.; Rewley, J.; Node, K.; Mizuno, A. The Time Trend of Information Seeking Behavior about Salt Reduction Using Google Trends: Infodemiological Study in Japan. Hypertens. Res. 2023, 46, 1886–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusumoto, K.-I.; Yamagata, Y.; Tazawa, R.; Kitagawa, M.; Kato, T.; Isobe, K.; Kashiwagi, Y. Japanese Traditional Miso and Koji Making. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimes, C.A.; Riddell, L.J.; Nowson, C.A. Consumer Knowledge and Attitudes to Salt Intake and Labelled Salt Information. Appetite 2009, 53, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhikara, N.; Jaglan, S.; Sindhu, N.; Venthodika, A.; Charan, M.V.S.; Panghal, A. Importance of Traceability in Food Supply Chain for Brand Protection and Food Safety Systems Implementation. Ann. Biol. 2018, 34, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Solieri, L. The Revenge of Zygosaccharomyces Yeasts in Food Biotechnology and Applied Microbiology. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, R.; Shim, Y.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Reaney, M.J.T.; Tse, T.J. Exploring Lactic Acid Bacteria in Food, Human Health, and Agriculture. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 8122–8148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Portugal Soybean and Products Market Outlook_Madrid_Spain_SP2023-0019.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Kaufman-shriqui, V.; Navarro, D.A.; Salem, H.; Boaz, M. Mediterranean Diet and Health—A Narrative Review. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2022, 12, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PortFIR. Available online: https://portfir-insa.min-saude.pt/foodcomp/food?26971 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- PortFIR. Available online: https://portfir-insa.min-saude.pt/foodcomp/food?26984 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- PortFIR. Available online: https://portfir-insa.min-saude.pt/foodcomp/food?27090 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- PortFIR. Available online: https://portfir-insa.min-saude.pt/foodcomp/food?26579 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Moreira, R.I.V. Impacto Da Seca Em Variedades Portuguesas de Feijão-Frade. Master’s Thesis, Faculdade de Medicina Vetetinária, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- PortFIR. Available online: https://portfir-insa.min-saude.pt/ (accessed on 9 July 2015).

- Odeku, O.A.; Ogunniyi, Q.A.; Ogbole, O.O.; Fettke, J. Forgotten Gems: Exploring the Untapped Benefits of Underutilized Legumes in Agriculture, Nutrition, and Environmental Sustainability. Plants 2024, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suezawa, Y.; Kimura, I.; Inoue, M.; Gohda, N.; Suzuki, M. Identification and Typing of Miso and Soy Sauce Fermentation Yeasts, Candida Etchellsii and C. Versatilis, Based on Sequence Analyses of the D1D2 Domain of the 26S Ribosomal RNA Gene, and the Region of Internal Transcribed Spacer 1, 5.8S Ribosomal RNA Gene and Internal Transcribed Spacer 2. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006, 70, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allwood, J.G.; Wakeling, L.T.; Bean, D.C. Microbial Ecology of Australian Commercial Rice Koji and Soybean Miso. JSFA Rep. 2023, 3, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunzel, M.; Schendel, R.R. Determination of (Total) Phenolics and Antioxidant Capacity in Food and Ingredients. In Food Analysis; Nielsen, S.S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 455–468. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Hao, S.; Ren, Q. Uncultured Microorganisms and Their Functions in the Fermentation Systems of Traditional Chinese Fermented Foods. Foods 2023, 12, 10324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yin, H.; Deng, Y. Transcriptome Analysis of Viable but Non-Culturable Brettanomyces Bruxellensis Induced by Hop Bitter Acids. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 902110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- İzgördü, Ö.K.; Darcan, C.; Kariptaş, E. Overview of VBNC, a Survival Strategy for Microorganisms. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, H.-F.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Wei, C.-I. Histamine and Other Biogenic Amines and Histamine-Forming Bacteria in Miso Products. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, B.H.; Kim, K.H.; Jeong, S.E.; Jeon, C.O. The Effect of Salt Concentrations on the Fermentation of Doenjang, a Traditional Korean Fermented Soybean Paste. Food Microbiol. 2020, 86, 103329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, S.; Liu, J.; Lu, J.; Wu, D. Effect of Salt Concentration on Chinese Soy Sauce Fermentation and Characteristics. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, E.; Selvi, S.S.; Nikerel, E.; Teusink, B.; Öner, E.T.; Çakır, T. A Genome-Sacle Metabolic Network of the Aroma Bacterium Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. cremoris. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 3153–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, K.; Nukagawa, Y.; Wakinaka, T.; Watanabe, J.; Mogi, Y. Application of a Low Acetate-Producing Strain of Tetragenococcus Halophilus to Soy Sauce Fermentation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2025, 139, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, H. Koji Starter and Koji World in Japan. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giang, N.T.N.; Van Khai, T.; Thuy, N.M. Optimization of Amylase and Protease Production from Oyster Mushrooms Koji (Pleurotus Spp.) Using Response Surface Methodology. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, B. Effects of Adding Proteins from Different Sources during Heat-Moisture Treatment on Corn Starch Structure, Physicochemical and in Vitro Digestibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 133079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovalino-Córdova, A.M.; Aguirre Montesdeoca, V.; Capuano, E. A Mechanistic Model to Study the Effect of the Cell Wall on Starch Digestion in Intact Cotyledon Cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 253, 117351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gidley, M.J.; Dhital, S. Wall Porosity in Isolated Cells from Food Plants: Implications for Nutritional Functionality. Food Chem. 2019, 279, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerda, A.; El-Bakry, M.; Gea, T.; Sánchez, A. Long Term Enhanced Solid-State Fermentation: Inoculation Strategies for Amylase Production from Soy and Bread Wastes by Thermomyces Sp. in a Sequential Batch Operation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 2394–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manassero, C.A.; David-briand, E.; Vaudagna, S.R.; Anton, M.; Speroni, F. Calcium Addition, PH, and High Hydrostatic Pressure Effects on Soybean Protein Isolates—Part 1: Colloidal Stability Improvement. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2018, 11, 1125–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manassero, C.A.; Vaudagna, S.R.; Anón, M.C.; Speroni, F. High Hydrostatic Pressure Improves Protein Solubility and Dispersion Stability of Mineral-Added Soybean Protein Isolate. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 43, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, V.R.; Russell, K.A.; Gregory, J.F. Vitamin B6. In Present Knowledge in Nutrition, 10th ed.; Erdman, J.W., MacDonald, I.A., Zeisel, S.H., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2012; pp. 230–247. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, P.B.; Footitt, E.J.; Clayton, P.T. Vitamin B6. In Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition, 4th ed.; Caballero, B., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 489–503. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.; Alli, I.; Ismail, A.; Kermasha, S. Protein-Phenolic Interactions in Food. Eurasian J. Anal. Chem. 2012, 7, 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, L.; Wan, B.; Feng, X.; Huang, Q.; Tan, W.; Wang, X. Phytase-Mediated Hydrolysis of Different Soil Phytate Species: Kinetics and Mineral Interfacial Mechanisms. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2025, 403, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, E.V.; Nogueira, A.R.A. Orthophosphate, Phytate, and Total Phosphorus Determination in Cereals by Flow Injection Analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 1800–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Chou, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-E.; Lai, Y.-T.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Tsai, T.; Lin, Y.-H.; Permatasari, S.S.; Lin, H.; Cheng, K.-C. Enhancing Miso Production with Optimized Puffed-Rice Koji and Its Biological Function Evaluation. Food Biosci. 2024, 60, 104463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinussen, J.; Solem, C.; Holm, A.K.; Jensen, P.R. Engineering Strategies Aimed at Control of Acidification Rate of Lactic Acid Bacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013, 24, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamp, A.; Kaltschmitt, M.; Lüdtke, O. Protein Recovery from Bioethanol Stillage by Liquid Hot Water Treatment. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2020, 155, 104624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes, S.A.; Mitrea, L.; Teleky, B.E.; Dulf, E.H.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Ranga, F.; Elekes, D.-G.A.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Dulf, F.V.; Vodnar, D.C. Integration of Ultrasound and Microwave Pretreatments with Solid-State Fermentation Enhances the Release of Sugars, Organic Acids, and Phenolic Compounds in Wheat Bran. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, A.; Barros, L.; Fernandes, Â.; Carvalho, A.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Valorization of Traditional Foods: Nutritional and Bioactive Properties of Cicer arietinum L. and Lathyrus sativus L. Pulses. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anande, Y.N.; Raut, P.K.; Zinjade, A.S.; Mane, S.B. Production of Citric Acid from Different Aspergillus Species Obtained from Soil. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 23, 2008–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfalleh, W.; Sun, C.; He, S.; Kong, B.; Ma, Y. Changes in Enzymatic Activities during “Koji” Incubation and Natural Fermentation of Soybean Paste. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, A.; Osako, K.; Okamoto, A.; Okazaki, E.; Ohshima, T. Effects of Koji Fermented Phenolic Compounds on the Oxidative Stability of Fish Miso. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, C228–C235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborti, M.; Banik, A.K. Effect of Minerals (Macro and Micro) on Alcohol Dehydrogenase and Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Activity during Acetic Acid Production by an Ethanol Resistant Strain of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae AB 100. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2011, 88, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar]

- Belviso, S.; Bardi, L.; Bartolini, A.B.; Marzona, M. Lipid Nutrition of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae in Winemaking. Can. J. Microbiol. 2004, 50, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nutritional Component | Soybean | Chickpea | Lupin | Cowpea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates (g) | 5.6 1 | 16.7 | 7.2 | 18.1 |

| Starch (g) | 2 | 15.1 | 6.7 | 16.4 |

| Fibre (g) | 5.6 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| Protein (g) | 12.5 | 8.4 | 16 | 8.8 |

| Fat (g) | 7.5 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 0.7 |

| Vitamins | ||||

| Thiamine (mg) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 0.19 |

| Pyridoxine (mg) | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.1 |

| Folate (µg) | 64 | 54 | 84.5 | 210 |

| Minerals | ||||

| Potassium (mg) | 510 | 270 | 250 | 320 |

| Calcium (mg) | 82 | 46 | 48 | 21 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 240 | 83 | 110 | 140 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 84 | 39 | 54 | 47 |

| Iron (mg) | 2.6 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 1.9 |

| Zinc (mg) | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| Microorganism (log10 CFU/g Fresh Biomass) | Time (Day) | Alternative Legume-Based Misos | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM3 | CM12 | LM3 | LM12 | CoM3 | CoM12 | ||

| Yeasts | 0 | 5.441 ± 0.009 | 4.090 ± 0.148 | 5.401 ± 0.064 | 5.744 ± 0.061 | 5.672 ± 0.052 | 5.280 ± 0.050 |

| 15 | 3.597 ± 0.039 | 3.638 ± 0.136 | 7.180 ± 0.002 | 5.158 ± 0.090 | 6.436 ± 0.016 | 6.866 ± 0.004 | |

| 30 | 6.027 ± 0.038 | 3.380 ± 0.157 | 5.833 ± 0.247 | 3.423 ± 0.035 | 5.352 ± 0.008 | 3.744 ± 0.141 | |

| 60 | NCC | NCC | 3.866 ± 0.004 | 3.889 ± 0.184 | 3.498 ± 0.108 | NCC | |

| 90 | NCC | NCC | NCC | 4.922 ± 0.063 | 3.591 ± 0.016 | NCC | |

| 180 | NCC | NCC | NCC | NCC | 3.932 ± 0.098 | NCC | |

| 270 | NCC | NCC | NCC | NCC | NCC | NCC | |

| LAB | 0 | 8.276 ± 0.092 | 5.623 ± 0.015 | 4.740 ± 0.090 | 5.009 ± 0.030 | 6.623 ± 0.001 | 6.208 ± 0.067 |

| 15 | 6.613 ± 0.060 | 5.106 ± 0.060 | 4.607 ± 0.053 | 3.591 ± 0.111 | 4.968 ± 0.007 | 4.633 ± 0.072 | |

| 30 | 4.964 ± 0.013 | 3.884 ± 0.020 | 3.985 ± 0.244 | 3.854 ± 0.030 | 6.158 ± 0.001 | 5.055 ± 0.158 | |

| 60 | 5.602 ± 0.046 | 3.544 ± 0.035 | 3.591 ± 0.001 | 4.602 ± 0.015 | 3.942 ± 0.132 | 3.519 ± 0.037 | |

| 90 | 4.164 ± 0.248 | NCC | NCC | 4.460 ± 0.014 | 4.190 ± 0.129 | 3.672 ± 0.013 | |

| 180 | 5.276 ± 0.036 | NCC | NCC | NCC | 3.695 ± 0.043 | 3.380 ± 0.103 | |

| 270 | NCC | NCC | NCC | NCC | NCC | NCC | |

| Parameters | Time (Months) | Alternative Legume-Based Misos | Soybean-Based Misos | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM3 | CM12 | LM3 | LM12 | CoM3 | CoM12 | SM3 | SM12 | ||

| pH | 0 | 4.993 ± 0.015 d; (e) | 5.333 ± 0.025 c; (c) | 4.637 ± 0.021 h; (k) | 4.633 ± 0.012 h; (k) | 5.580 ± 0.010 a; (a) | 5.517 ± 0.006 b; (b) | 5.130 ± 0.032 (d) | 5.070 ± 0.020 (d) |

| 18 | 4.797 ± 0.025 g; (j) | 4.830 ± 0.010 f; (i) | 4.223 ± 0.015 j; (m) | 4.467 ± 0.006 i; (l) | 4.837 ± 0.006 f; (i) | 4.973 ± 0.006 e; (f) | 4.877 ± 0.006 (h) | 4.937 ± 0.006 (g) | |

| TSS | 0 | 14.667 ± 0.577 h; (h) | 12.000 ± 0.000 j; (j) | 9.000 ± 0.000 k; (l) | 13.333 ± 0.577 i; (i) | 21.000 ± 0.000 g; (g) | 12.000 ± 0.000 j; (j) | 10.000 ± 0.000 (k) | 25.667 ± 0.577 (f) |

| 18 | 44.000 ± 0.000 c; (b) | 52.000 ± 0.577 a; (a) | 35.000 ± 0.000 f; (e) | 41.000 ± 0.000 d; (c) | 44.667 ± 0.577 b; (b) | 37.667 ± 0.577 e; (d) | 35.000 ± 0.000 (e) | 35.000 ± 1.000 (e) | |

| Soluble Protein (mg/100 g) | 0 | 27.539 ± 0.463 cd; (c) | 25.243 ± 0.206 de; (d) | 9.172 ± 0.679 h; (h) | 9.495 ± 1.156 h; (h) | 17.522 ± 0.416 ef; (ef) | 16.638 ± 0.588 f; (f) | 21.332 ± 0.579 (e) | 25.328 ± 0.078 (d) |

| 18 | 145.799 ± 8.988 ab; (a) | 148.690 ± 10.067 a; (a) | 46.473 ± 2.718 bc; (b) | 10.827 ± 0.368 g; (g) | 5.861 ± 0.793 i; (i) | 9.500 ± 1.767 h; (h) | 40.588 ± 4.847 (b) | 40.384 ± 3.915 (b) | |

| Soluble Phenolic Compounds (mg GAE/100 g) | 0 | 5.024 ± 0.254 h; (k) | 4.424 ± 0.311 i; (l) | 3.803 ± 0.100 j; (m) | 5.830 ± 0.189 f; (i) | 5.634 ± 0.094 g; (j) | 3.585 ± 0.100 k; (n) | 4.196 ± 0.136 (l) | 9.797 ± 0.435 (h) |

| 18 | 36.572 ± 0.671 a; (a) | 29.816 ± 0.906 b; (d) | 15.474 ± 1.016 d; (f) | 20.269 ± 0.987 c; (e) | 12.423 ± 1.199 e; (g) | 12.118 ± 1.310 e; (g) | 34.611 ± 0.400 (b) | 32.693 ± 1.953 (c) | |

| Reducing Sugar (g/100 g) | |||||||||

| Maltotriose | 0 | 1.142 ± 0.055 b; (b) | 0.709 ± 0.034 d; (d) | 0.909 ± 0.058 c; (c) | 1.011 ± 0.062 c; (c) | 1.207 ± 0.073 ab; (ab) | 1.807 ± 0.016 a; (a) | 0.495 ± 0.030 (g) | 0.498 ± 0.014 (g) |

| 18 | 0.391 ± 0.002 g; (h) | 0.452 ± 0.031 fg; (h) | 0.729 ± 0.005 d; (d) | 0.722 ± 0.099 de; (de) | 0.497 ± 0.010 f; (g) | 0.634 ± 0.007 e; (ef) | 0.994 ± 0.021 (c) | 0.610 ± 0.038 (f) | |

| Maltose | 0 | 1.866 ± 0.093 b; (b) | 1.737 ± 0.088 c; (c) | 1.396 ± 0.004 e; (de) | 1.951 ± 0.017 b; (b) | 1.596 ± 0.007 d; (d) | 2.745 ± 0.024 a; (a) | 0.308 ± 0.006 (j) | 0.386 ± 0.013 (j) |

| 18 | 0.775 ± 0.008 h; (g) | 0.615 ± 0.046 i; (g) | 0.378 ± 0.001 j; (i) | 0.390 ± 0.026 j; (i) | 0.863 ± 0.006 g; (f) | 0.977 ± 0.010 f; (e) | 0.881 ± 0.025 (f) | 0.425 ± 0.016 (h) | |

| Glucose | 0 | 1.645 ± 0.085 l; (m) | 4.694 ± 0.223 f; (g) | 2.812 ± 0.148 h; (i) | 3.057 ± 0.027 g; (h) | 1.805 ± 0.011 k; (l) | 2.224 ± 0.017 j; (k) | 0.438 ± 0.038 (o) | 0.904 ± 0.061 (n) |

| 18 | 12.322 ± 0.114 b; (b) | 12.806 ± 0.223 a; (a) | 2.495 ± 0.063 i; (j) | 8.366 ± 0.099 d; (d) | 7.989 ± 0.316 e; (e) | 11.282 ± 0.469 c; (c) | 12.992 ± 0.288 (a) | 6.922 ± 0.373 (f) | |

| Fructose | 0 | 0.119 ± 0.007 h; (jk) | 0.304 ± 0.013 d; (fg) | 0.136 ± 0.018 g; (j) | 0.129 ± 0.004 gh; (i) | 0.177 ± 0.002 f; (i) | 0.238 ± 0.003 e; (hi) | 0.081 ± 0.07 (k) | 0.132 ± 0.021 (j) |

| 18 | 0.694 ± 0.028 a; (a) | 0.606 ± 0.026 a; (bc) | 0.247 ± 0.009 e; (gh) | 0.553 ± 0.012 b; (cd) | 0.497 ± 0.043 c; (ef) | 0.504 ± 0.038 c; (de) | 0.652 ± 0.047 (ab) | 0.585 ± 0.050 (c) | |

| Organic Acids (g/100 g) | |||||||||

| Latic | 0 | 0.067 ± 0.006 e; (f) | 0.182 ± 0.019 b; (cd) | 0.021 ± 0.003 g; (h) | 0.037 ± 0.009 f; (g) | 0.036 ± 0.007 f; (g) | 0.024 ± 0.003 g; (h) | 0.058 ± 0.006 (f) | 0.043 ± 0.002 (g) |

| 18 | 0.690 ± 0.012 a; (f) | 0.276 ± 0.029 ab; (ab) | 0.067 ± 0.013 e; (f) | 0.138 ± 0.006 c; (de) | 0.129 ± 0.005 cd; (e) | 0.127 ± 0.012 d; (e) | 0.059 ± 0.011 (f) | 0.250 ± 0.008 (bc) | |

| Acetic | 0 | 0.103 ± 0.004 d; (gh) | 0.041 ± 0.004 e; (i) | 0.036 ± 0.005 ef; (ij) | 0.041 ± 0.009 e; (i) | 0.026 ± 0.005 g; (k) | 0.031 ± 0.007 fg; (jk) | 0.159 ± 0.009 (e) | 0.114 ± 0.012 (fg) |

| 18 | 0.361 ± 0.018 a; (a) | 0.275 ± 0.013 bc; (cd) | 0.259 ± 0.009 c; (de) | 0.318 ± 0.017 ab; (bc) | 0.116 ± 0.007 d; (fg) | 0.127 ± 0.018 d; (f) | 0.075 ± 0.003 (h) | 0.368 ± 0.034 (ab) | |

| Citric | 0 | 0.082 ± 0.009 f; (i) | 0.113 ± 0.008 de; (gh) | 0.040 ± 0.009 g; (j) | 0.034 ± 0.002 g; (j) | 0.098 ± 0.014 e; (hi) | 0.115 ± 0.008 d; (g) | 0.030 ± 0.001 (k) | 0.033 ± 0.003 (j) |

| 18 | 0.597 ± 0.020 a; (ab) | 0.640 ± 0.011 a; (a) | 0.322 ± 0.017 c; (ef) | 0.544 ± 0.006 b; (bc) | 0.502 ± 0.038 b; (cd) | 0.379 ± 0.022 c; (e) | 0.284 ± 0.011 b(f) | 0.484 ± 0.024 (d) | |

| Malic | 0 | 0.104 ± 0.007 g; (hi) | 0.121 ± 0.010 fg; (g) | 0.092 ± 0.007 h; (ij) | 0.093 ± 0.001 h; (j) | 0.109 ± 0.016 g; (h) | 0.124 ± 0.006 f; (g) | 0.117 ± 0.011 (gh) | 0.127 ± 0.002 (g) |

| 18 | 1.316 ± 0.008 a; (a) | 1.193 ± 0.042 ab; (ab) | 0.758 ± 0.030 de; (de) | 1.108 ± 0.010 bc; (b) | 1.057 ± 0.048 cd; (bc) | 0.580 ± 0.018 e; (ef) | 0.471 ± 0.007 (f) | 0.807 ± 0.025 (cd) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, R.; Parente, B.; Mota, M.; Raymundo, A.; Prista, C. Fermentation Process Evaluation of a Sustainable and Innovative Miso Made from Alternative Legumes. Foods 2025, 14, 4131. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234131

Santos R, Parente B, Mota M, Raymundo A, Prista C. Fermentation Process Evaluation of a Sustainable and Innovative Miso Made from Alternative Legumes. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4131. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234131

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Rafaela, Beatriz Parente, Mariana Mota, Anabela Raymundo, and Catarina Prista. 2025. "Fermentation Process Evaluation of a Sustainable and Innovative Miso Made from Alternative Legumes" Foods 14, no. 23: 4131. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234131

APA StyleSantos, R., Parente, B., Mota, M., Raymundo, A., & Prista, C. (2025). Fermentation Process Evaluation of a Sustainable and Innovative Miso Made from Alternative Legumes. Foods, 14(23), 4131. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234131