Investigating the Impact of Amylopectin Chain-Length Distribution on the Structural and Functional Properties of Waxy Rice Starch

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Total Starch and Crude Protein Content

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.4. Size-Exclusion Chromatography

2.5. Fluorophore-Assisted Carbohydrate Electrophoresis and Model Fitting

2.6. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

2.7. Small Angle X-Ray Scattering

2.8. Rapid Visco Analyzer

2.9. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

2.10. In Vitro Starch Digestibility and Model Fitting

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition

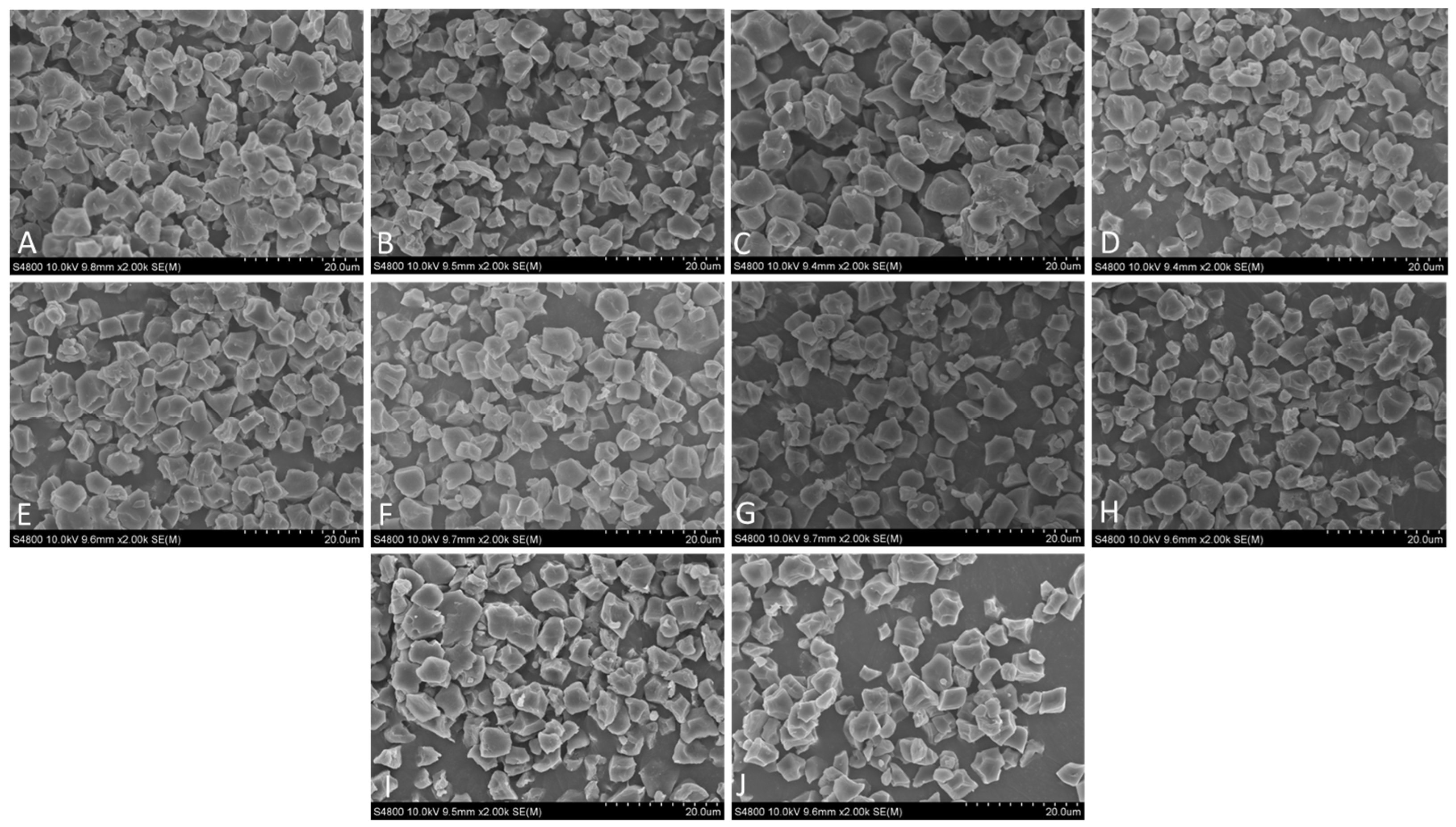

3.2. Starch Granule Morphology

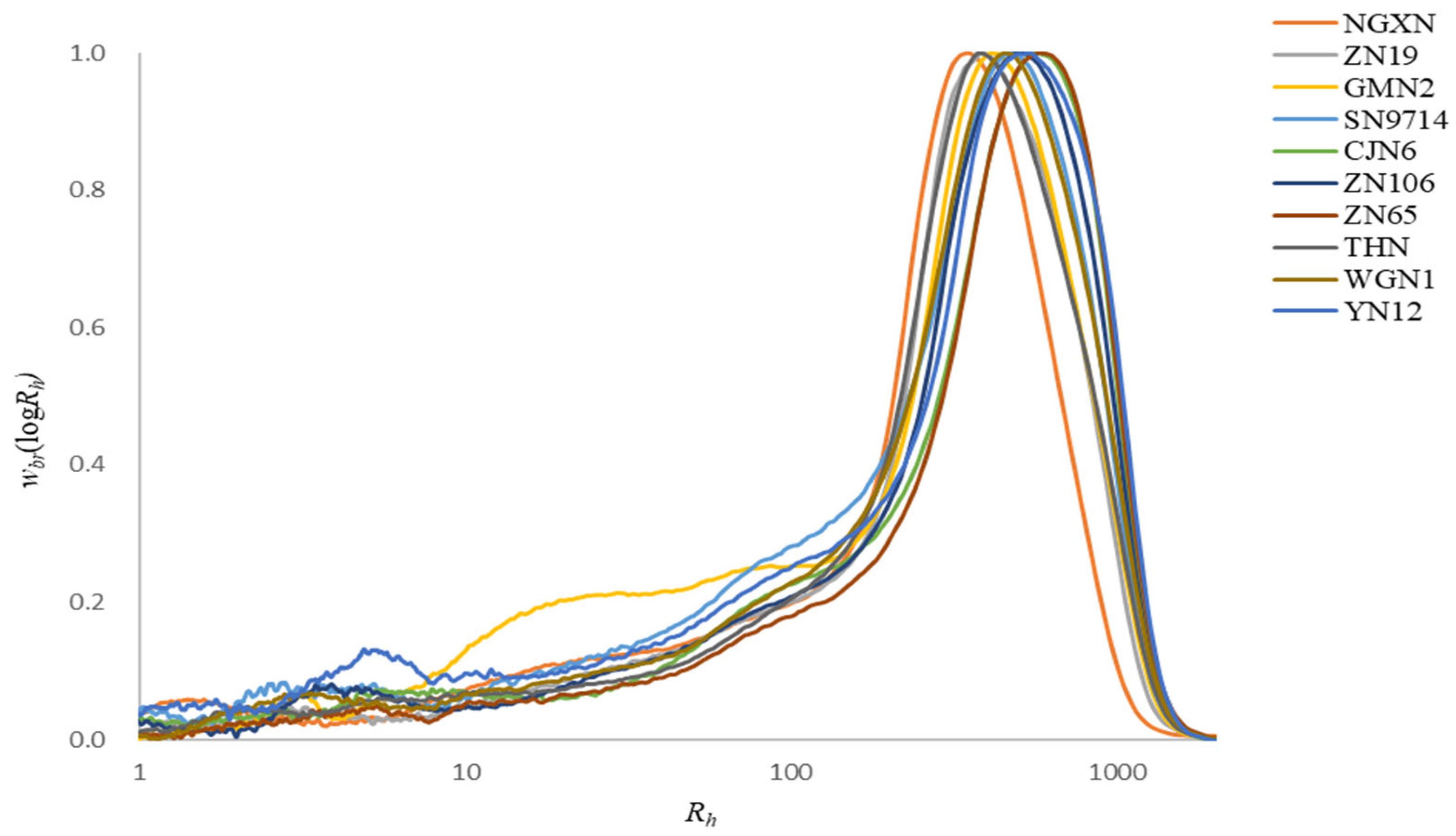

3.3. Molecular Size Distribution of Fully Branched Waxy Rice Starches

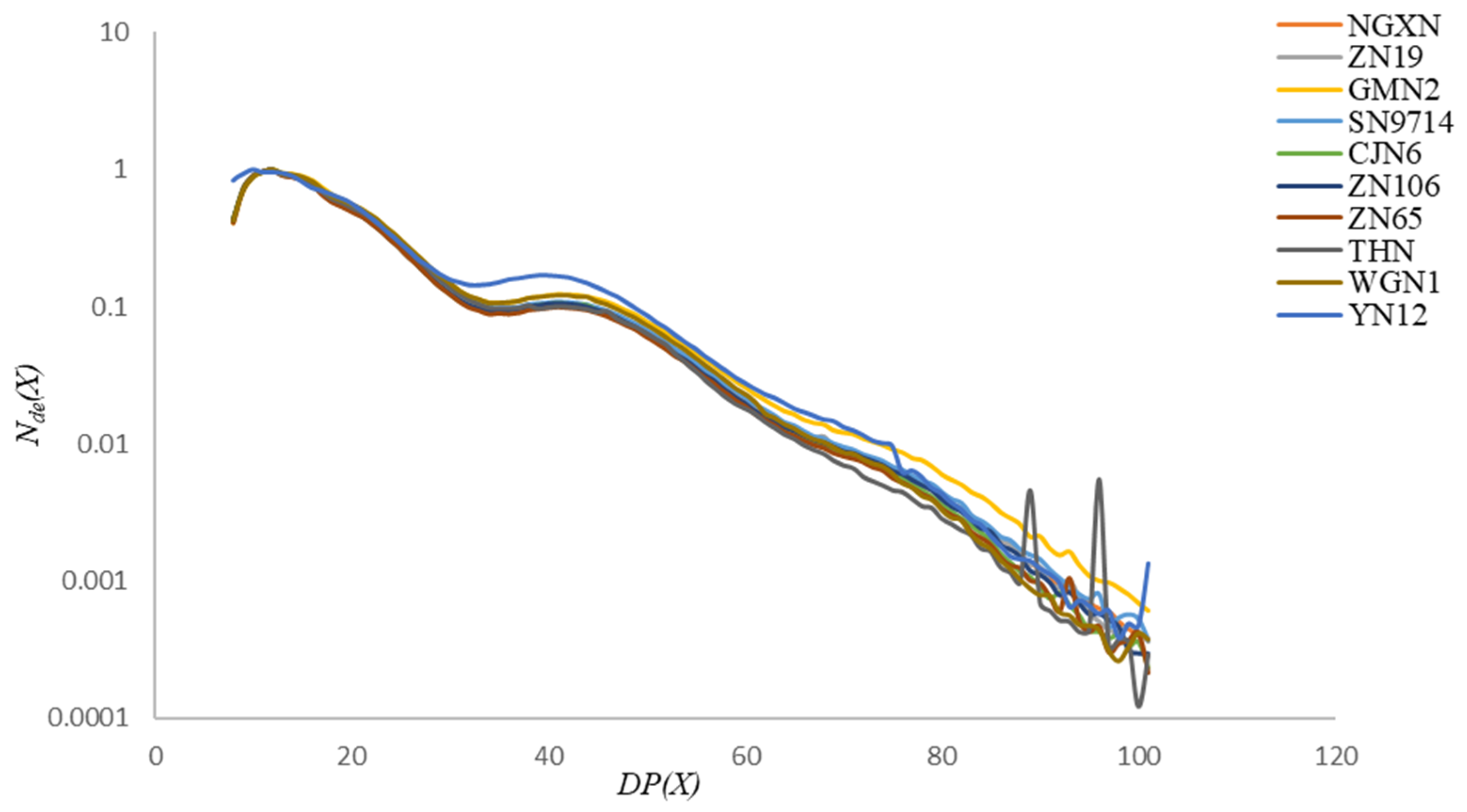

3.4. Structural Analysis of Amylopectin Chain-Length Distribution

3.5. Biosynthesis Model for Amylopectin CLD Fitting

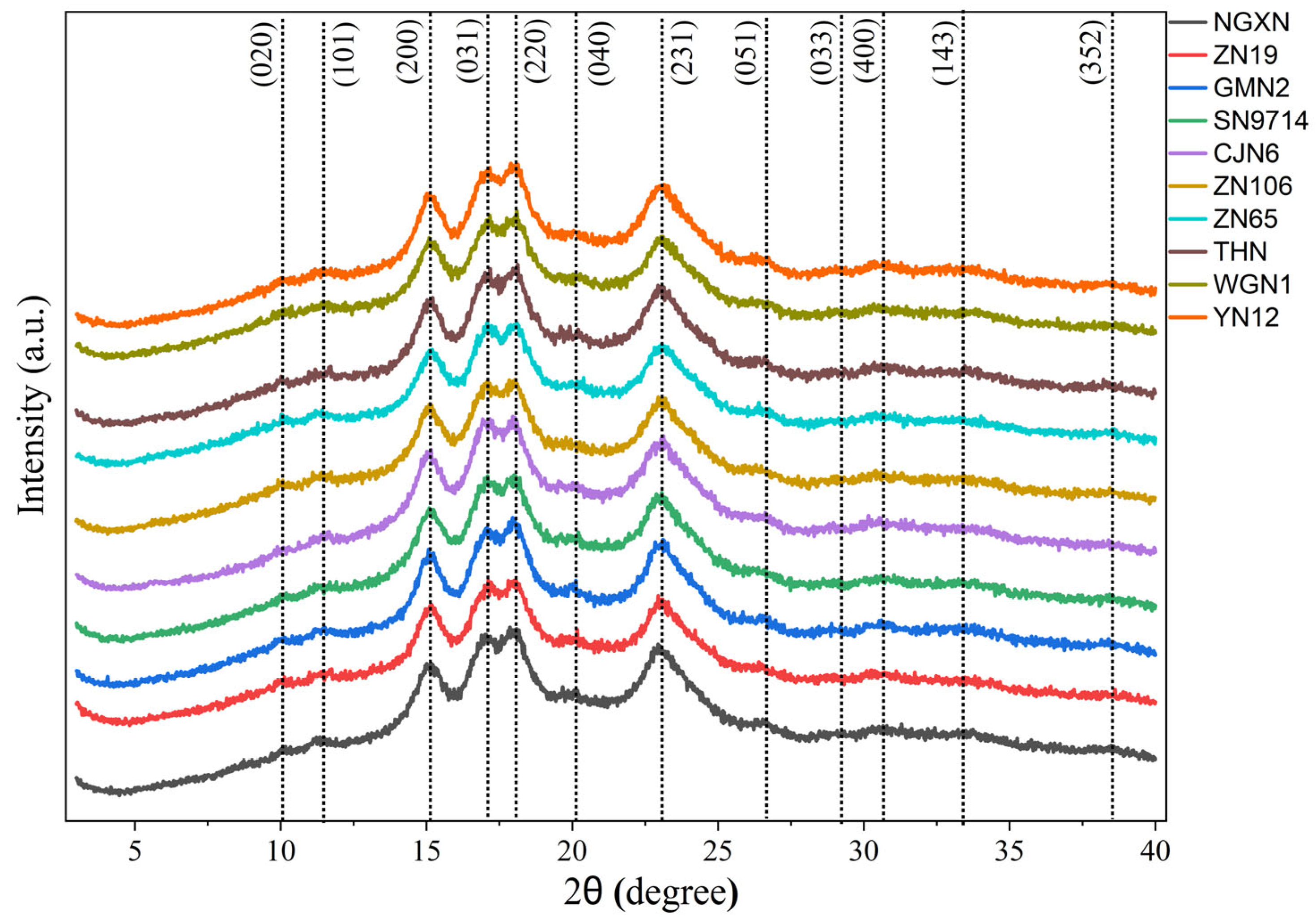

3.6. Relative Crystallinity

3.7. Lamellar Structure

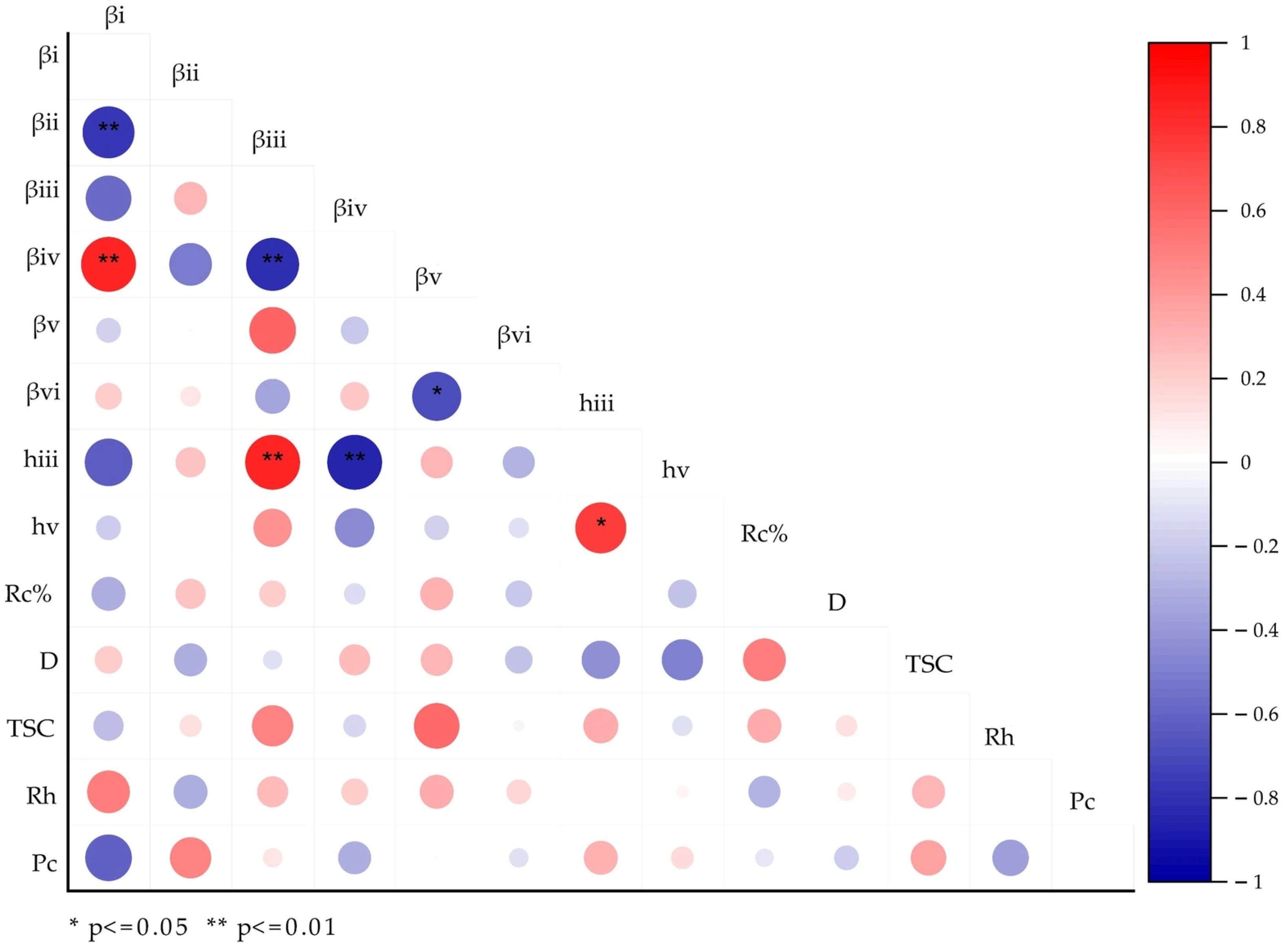

3.8. Structural Correlation Analysis

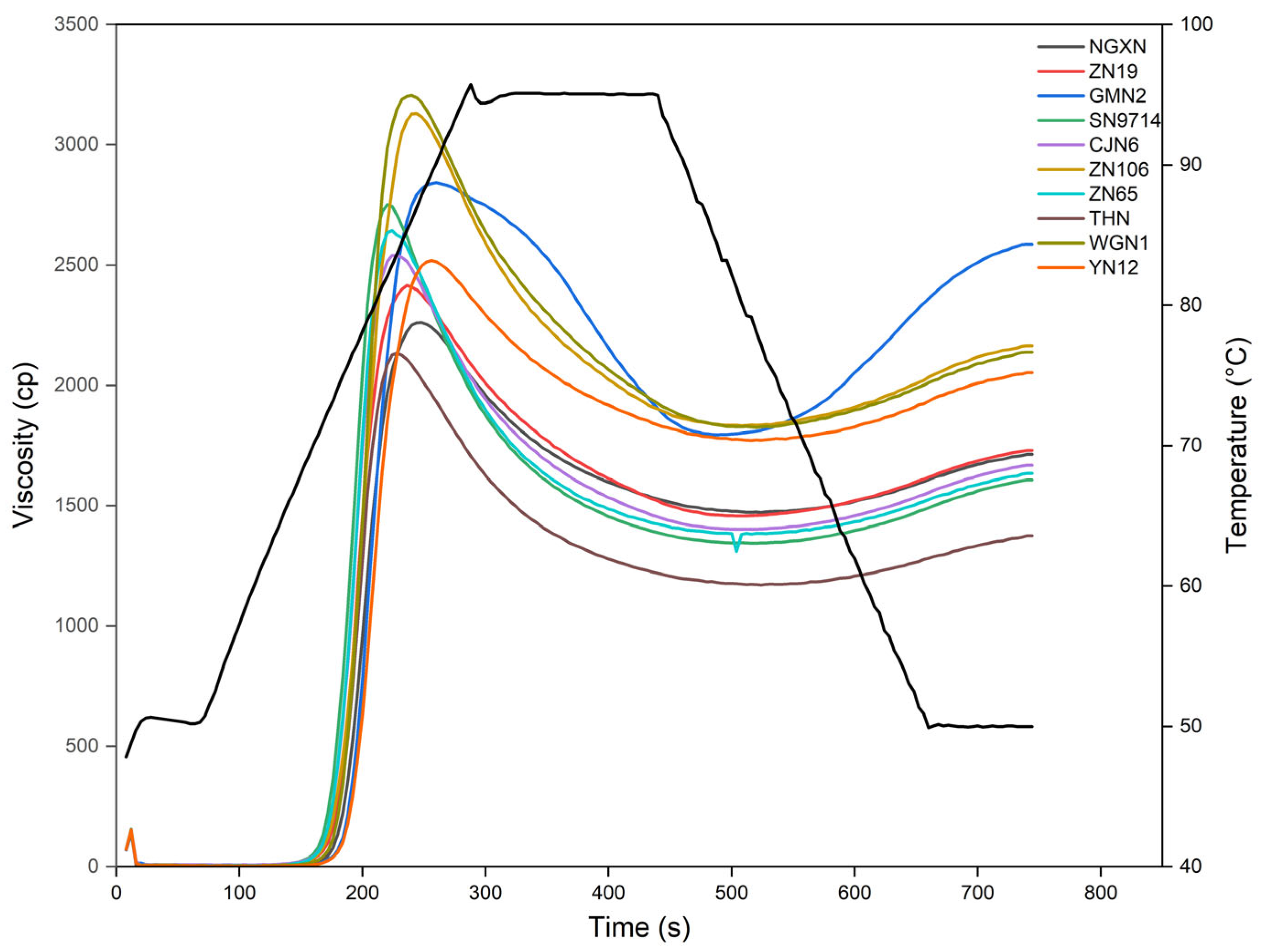

3.9. Pasting Properties

3.10. Thermal Properties

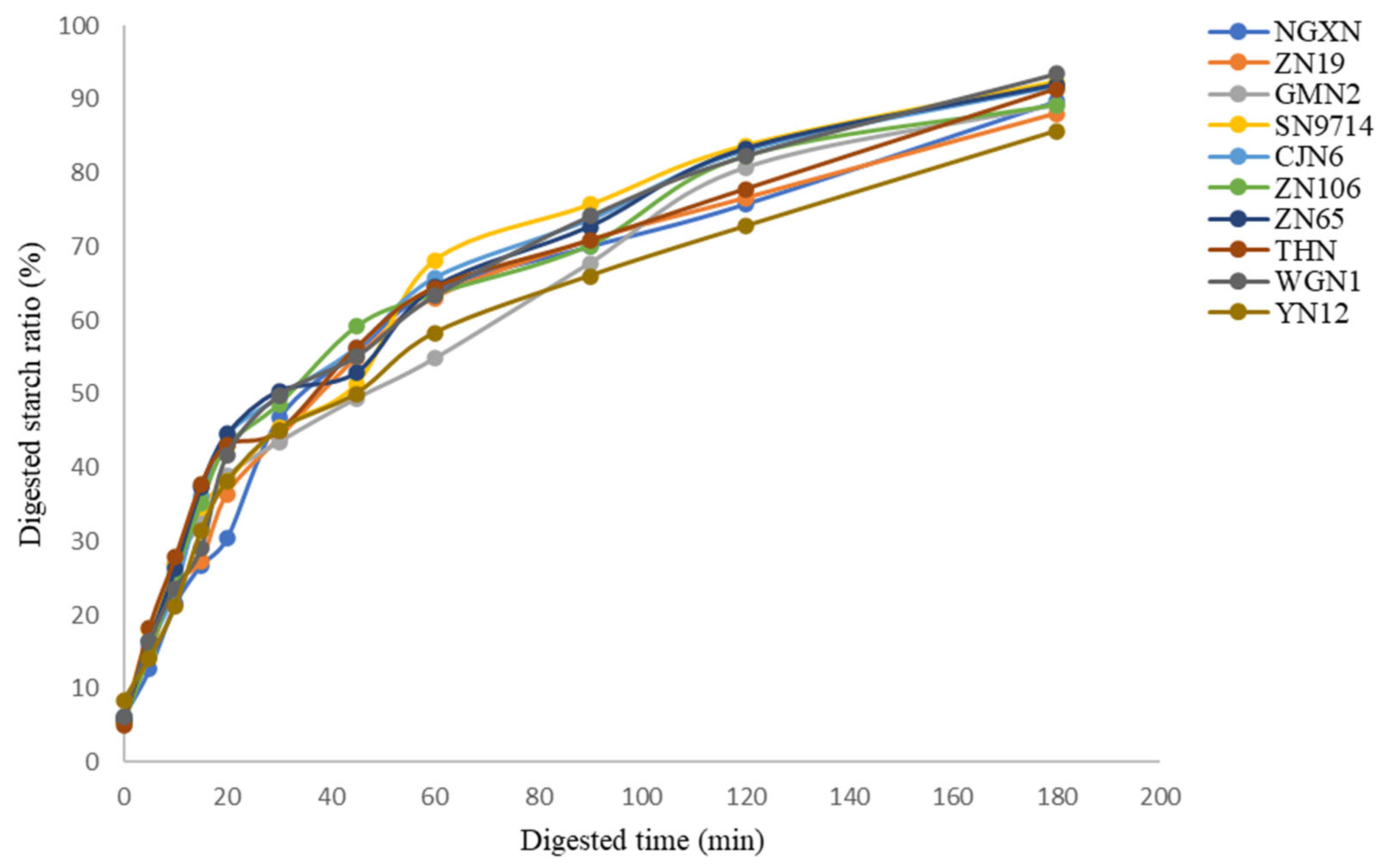

3.11. In Vitro Starch Digestibility

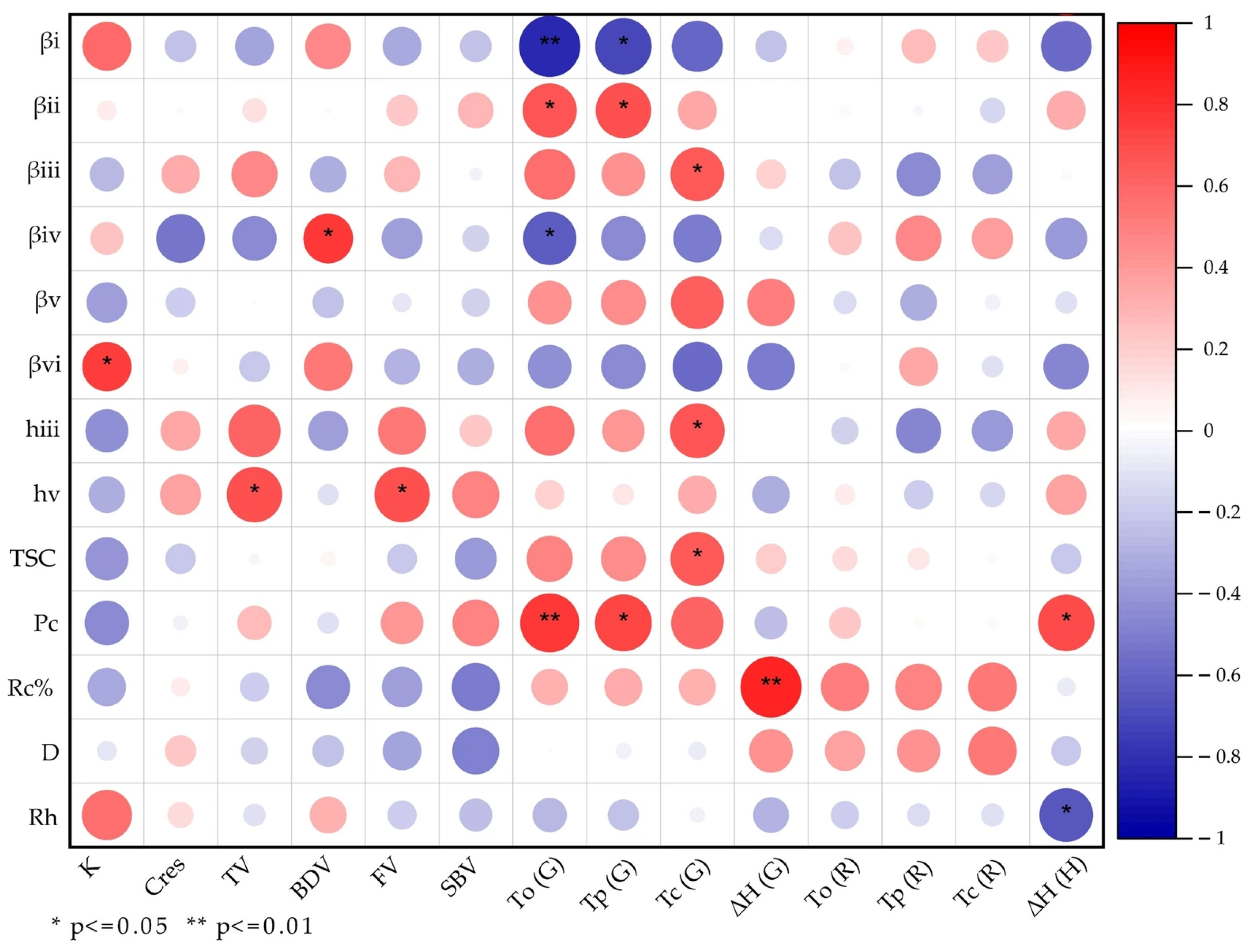

3.12. Correlation Analysis Between Structural Parameters and Functional Characteristics

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu, Y.; Hua, Y.; Luo, T.; Liu, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Tao, Y.; Zhu, Z. Generating waxy rice starch with target type of amylopectin fine structure and gelatinization temperature by waxy gene editing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 306, 120595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazek, J.; Gilbert, E.P. Application of small-angle X-ray and neutron scattering techniques to the characterisation of starch structure: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 85, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.Y.; Lim, S.T.; Lee, J.H.; Chung, H.J. Impact of molecular and crystalline structures on in vitro digestibility of waxy rice starches. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 112, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.H.; Singh, H.; Ciao, J.Y.; Kao, W.T.; Huang, W.H.; Chang, Y.H. Genotype diversity in structure of amylopectin of waxy rice and its influence on gelatinization properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 1858–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, Q.; Gilbert, R.G. The effects of chain-length distributions on starch-related properties in waxy rices. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 339, 122264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, C.; Ma, Z.; Chen, H.; Gao, H. Toward an understanding of potato starch structure, function, biosynthesis, and applications. Food Front. 2023, 4, 980–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.H.; Xu, C.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Ji, S.Y.; Ren, Y.C.; Chen, Z.Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, B.; Lu, B.Y. Investigating the evolution of the fine structure in cassava starch during growth and its correlation with gelatinization performance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 265, 130422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, E.; Fan, X.; Yang, C.; Ma, H.; Gilbert, R.G. The effects of the chain-length distributions of starch molecules on rheological and thermal properties of wheat flour paste. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 101, 105563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Tai, L.; Blennow, A.; Ding, L.; Herburger, K.; Qu, J.; Xin, A.; Guo, D.; Hebelstrup, K.H.; Liu, X. High-amylose starch: Structure, functionality and applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 8568–8590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Li, E.; Khalifa, I.; Walayat, N.; Liu, J.; Irshad, S.; Zahra, A.; Ahmed, S.; Simirgiotis, M.J.; Pateiro, M. Effect of different processing methods on quality, structure, oxidative properties and water distribution properties of fish meat-based snacks. Foods 2021, 10, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaichoompu, E.; Ruengphayak, S.; Wattanavanitchakorn, S.; Wansuksri, R.; Yonkoksung, U.; Suklaew, P.O.; Chotineeranat, S.; Raungrusmee, S.; Vanavichit, A.; Toojinda, T. Development of Whole-Grain Rice Lines Exhibiting Low and Intermediate Glycemic Index with Decreased Amylose Content. Foods 2024, 13, 3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liang, C.; Liu, J.; Zhou, C.; Wu, Z.; Guo, S.; Liu, J.; A, N.; Wang, S.; Xin, G.; et al. Moderate Reduction in Nitrogen Fertilizer Results in Improved Rice Quality by Affecting Starch Properties without Causing Yield Loss. Foods 2023, 12, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.W.; Li, C.M.; Gu, Z.B.; Qiu, Y.J.; Cheng, L.; Hong, Y.; Li, Z.F. Relationship between structure and retrogradation properties of corn starch treated with 1,4-alpha-glucan branching enzyme. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.L.; Chang, Y.H.; Ko, W.C.; Sriroth, K.; Huang, T.C. Influence of amylopectin structure and amylose content on the gelling properties of five cultivars of cassava starches. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2717–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, J.; Chen, S.; Fan, X.; Li, Q.; Lu, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, H.; Yi, C.; Tang, S. Wxlv, the ancestral allele of rice Waxy gene. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Cao, P.; Wu, P.; Yu, W.; Gilbert, R.G.; Li, E. Effects of endogenous proteins on rice digestion during small intestine (in vitro) digestion. Food Chem. 2021, 344, 128687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, Z.; Hettiarachchy, N.; Rath, N. Extraction, denaturation and hydrophobic properties of rice flour proteins. J. Food Sci. 2001, 66, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Gong, B.; Gilbert, R.G.; Yu, W.; Li, E.; Li, C. Relations between changes in starch molecular fine structure and in thermal properties during rice grain storage. Food Chem. 2019, 295, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahariza, Z.A.; Li, E.; Hasjim, J. Extraction and dissolution of starch from cereal grains for accurate structural analysis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Prakesh, S.; Nicholson, T.H.; Fitzgerald, M.A.; Gilbert, R.G. The importance of amylose and amylopectin fine structure for textural properties of cooked rice grains. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cave, R.A.; Seabrook, S.A.; Gidley, M.J.; Gilbert, R.G. Characterization of starch by size-exclusion chromatography: The limitations imposed by shear scission. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 2245–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.C.; Li, E.; Gilbert, R.G. Exploring extraction/dissolution procedures for analysis of starch chain-length distributions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 114, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.C.; Gilbert, R.G. Molecular weight distributions of starch branches reveal genetic constraints on biosynthesis. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 3539–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Gao, W.; Jia, W.; Xiao, P. Crystallography, morphology and thermal properties of starches from four different medicinal plants of Fritillaria species. Food Chem. 2006, 96, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Wang, P.; Huang, J.; Chen, S.; Li, D.; Pu, S.; Li, J.; Wen, J. Structural and physicochemical properties of rice starch from a variety with high resistant starch and low amylose content. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1413923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hu, Y.; Gu, F.; Gong, B. Causal relations among starch fine molecular structure, lamellar/crystalline structure and in vitro digestion kinetics of native rice starch. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 682–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chao, C.; Yu, J.; Copeland, L.; Wang, S. New insight into starch retrogradation: The effect of short-range molecular order in gelatinized starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 120, 106921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Cheng, L.; Gilbert, R.G.; Li, C. Distribution of short to medium amylose chains are major controllers of in vitro digestion of retrograded rice starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 96, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Dhital, S.; Gidley, M.J.; Gilbert, R.G. A more general approach to fitting digestion kinetics of starch in food. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 225, 115244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Wu, S.; Lai, S.; Ye, F. Effects of Stir-Frying and Heat–Moisture Treatment on the Physicochemical Quality of Glutinous Rice Flour for Making Taopian, a Traditional Chinese Pastry. Foods 2024, 13, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, Z.; Liu, L.; Cao, F.; Chen, J.; Huang, M. Relationships between texture properties of cooked rice with grain amylose and protein content in high eating quality indica rice. Cereal Chem. 2024, 101, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Copeland, L. Molecular disassembly of starch granules during gelatinization and its effect on starch digestibility: A review. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 1564–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhao, S.; Qiao, D.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, B.; Xie, F. Multiscale structural disorganization of indica rice starch under microwave treatment with high water contents. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xu, X.; Hemar, Y.; Mo, G.; de Campo, L.; Gilbert, E.P. Effect of porous waxy rice starch addition on acid milk gels: Structural and physicochemical functionality. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 109, 106092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Yao, Y. Small-granule starches from sweet corn and cow cockle: Physical properties and amylopectin branching pattern. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 74, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yi, X.; Yang, C.; Li, E. Starch fine molecular structures as driving factors for multiphasic starch gelatinization property in rice flour. Cereal Chem. 2023, 100, 816–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Zhang, J.; Shao, T.; Li, Y.; He, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Cao, R.; Li, A.; Du, X. Modification of Structure, Pasting, and In Vitro Digestion Properties of Glutinous Rice Starch by Different Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation. Foods 2025, 14, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yang, H.; Zhang, B.; Wu, L.; Huang, Q.; Zou, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, N. Effects of warming on starch structure, rice flour pasting property, and cooked rice texture in a double rice cropping system. Cereal Chem. 2022, 99, 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kang, X.; Hu, J.; Gao, W.; Cheng, Y.; Yu, B.; Sui, J.; Wang, J.; Cui, B. Evaluation of starch properties for selecting sorghum planted under environmental stress with superior noodle-making properties. Starch-Stärke 2023, 75, 2200265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, X.; Ma, C.; Wu, M.; Fan, Q.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Bian, X.; Zhang, N. Effects of extrusion technology on physicochemical properties and microstructure of rice starch added with soy protein isolate and whey protein isolate. Foods 2024, 13, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.C.; Morell, M.K.; Gilbert, R.G. A parameterized model of amylopectin synthesis provides key insights into the synthesis of granular starch. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sissons, M.; Palombieri, S.; Sestili, F.; Lafiandra, D. Impact of variation in amylose content on durum wheat cv. Svevo technological and starch properties. Foods 2023, 12, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Munoz, P.E.; Gutierrez-Cortez, E.; Hernandez-Urbiola, M.I.; Lopez-Leon, A.; Barron-Garcia, O.Y.; Rodriguez-Garcia, M.E. Physicochemical characterization of isolated nanocrystals in starch and isolated rice starch: A new perspective. Food Chem. 2025, 495, 146590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Garcia, M.E.; Hernandez-Landaverde, M.A.; Delgado, J.M.; Ramirez-Gutierrez, C.F.; Ramirez-Cardona, M.; Millan-Malo, B.M.; Londoño-Restrepo, S.M. Crystalline structures of the main components of starch. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 37, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Xu, X. Microstructure, gelatinization and pasting properties of rice starch under acid and heat treatments. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazek, J.; Salman, H.; Rubio, A.L.; Gilbert, E.; Hanley, T.; Copeland, L. Structural characterization of wheat starch granules differing in amylose content and functional characteristics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 75, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, F.; Zhang, J.; Qian, J.Y. Characterization of Corn Starch Granules Modified by Glucan 1, 4-α-Maltotriohydrolase from Microbacterium imperiale. Starch-Stärke 2023, 75, 2200259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yang, C.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Bai, Y.; Li, E.; Gilbert, R.G. Competition between granule bound starch synthase and starch branching enzyme in starch biosynthesis. Rice 2019, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, B.R.; Abraão, A.S.; Lemos, A.M.; Nunes, F.M. Chemical composition and functional properties of native chestnut starch (Castanea sativa Mill). Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 94, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.-X.; Chen, J.; Xu, F.; Chen, L.; Zhao, J.-W. Study on crystalline, gelatinization and rheological properties of japonica rice flour as affected by starch fine structure. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 1232–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Lu, C.; Yang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Li, Q.; Huang, L.; Fan, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C. The physicochemical properties of starch are affected by wxlv in indica rice. Foods 2021, 10, 3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Kawamata, K.; Okamoto, K. Comparison of starch physicochemical properties of waxy rice cultivars with different hardening rates. Cereal Chem. 2017, 94, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Z.; Yao, T.; Ye, X.; Bao, J.; Kong, X.; Wu, Y. Physicochemical properties and starch digestibility of in-kernel heat-moisture-treated waxy, low-, and high-amylose rice starch. Starch-Stärke 2017, 69, 1600164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez, G.; Ramirez-Gutierrez, C.F.; Mendez-Montealvo, G.; Velazquez-Castillo, R.; Morelos-Medina, L.F.; Morales-Sánchez, E.; Gaytán-Martínez, M.; Rodríguez-García, M.E.; Contreras-Jiménez, B. Effect of long-term retrogradation on the crystallinity, vibrational and rheological properties of potato, corn, and rice starches. Food Chem. 2025, 477, 143455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Miao, M. Dietary polyphenols modulate starch digestion and glycaemic level: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeva, K.; Srikaeo, K.; Sopade, P.A. Understanding starch digestibility of rice: A study in white rice. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 4849–4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Xie, F.; Li, L.; Huang, J. Effect of heat-moisture treatment on multi-scale structures and physicochemical properties of breadfruit starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 161, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, K.; Li, C.; Yu, W.; Gilbert, R.G.; Li, E. How amylose molecular fine structure of rice starch affects pasting and gelatinization properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 204, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahariza, Z.A.; Sar, S.; Tizzotti, M.; Hasjim, J.; Gilbert, R.G. The importance of amylose and amylopectin fine structures for starch digestibility in cooked rice grains. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Gilbert, R.G.; Li, S.; Li, E. Amylose inter-chain entanglement and inter-chain overlap impact rice quality. Foods 2022, 11, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.J.; Lai, P.Y.; Koh, Y.C.; Hung, C.C. Physicochemical characteristics and in vitro digestibility of indica, japonica, and waxy type rice flours and their derived resistant starch type III products. Starch-Stärke 2016, 68, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.-J.; Porter, R. Structures and physicochemical properties of six wild rice starches. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 2695–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Bi, J.; Gilbert, R.G.; Li, G.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Ding, Y. Amylopectin chain length distribution in grains of japonica rice as affected by nitrogen fertilizer and genotype. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 71, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Names | Sample Code | Total Starch Content (%) | Crude Protein Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nangengxiangnuo | NGXN | 83.35 ± 1.23 cde | 6.20 ± 0.08 de |

| Zhennuo19 | ZN19 | 85.13 ± 1.38 bcd | 7.18 ± 0.16 a |

| Guangmingnuo2 | GMN2 | 81.93 ± 0.50 e | 7.21 ± 0.09 a |

| Shaonuo9714 | SN9714 | 85.13 ± 1.53 bcd | 6.81 ± 0.15 b |

| Chunjiangnuo6 | CJN6 | 83.03 ± 0.58 de | 5.97 ± 0.28 e |

| Zhenuo106 | ZN106 | 82.39 ± 2.87 e | 6.18 ± 0.01 de |

| Zhenuo65 | ZN65 | 85.65 ± 0.43 abc | 6.46 ± 0.04 cd |

| Taihunuo | THN | 85.72 ± 0.81 abc | 6.69 ± 0.02 bc |

| Wangengnuo1 | WGN1 | 88.01 ± 1.16 a | 6.95 ± 0.06 ab |

| Yannuo12 | YN12 | 86.99 ± 1.12 ab | 6.84 ± 0.04 b |

| Varieties | ꞵi/10−2 | ꞵii/10−2 | ꞵiii/10−2 | βiv/10−2 | ꞵv/10−2 | βvi/10−2 | hiii/10−2 | hv/10−2 | Rh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGXN | 9.22 ± 0.11 a | 1.38 ± 0.47 a | 6.01 ± 0.22 b | 2.48 ± 0.14 ab | 7.39 ± 0.35 a | 1.58 ± 0.45 ab | 7.92 ± 1.24 b | 0.32 ± 0.06 b | 317.84 ± 14.71 d |

| ZN19 | 9.25 ± 0.71 a | 1.25 ± 0.12 ab | 5.94 ± 1.48 b | 2.46 ± 0.18 ab | 6.83 ± 0.38 a | 2.17 ± 0.39 ab | 7.87 ± 0.21 b | 0.31 ± 0.00 b | 363.75 ± 15.71 bc |

| GMN2 | 8.68 ± 0.83 a | 2.15 ± 0.42 a | 6.26 ± 1.27 b | 1.80 ± 0.01 ab | 7.09 ± 1.12 a | 1.02 ± 0.64 b | 10.15 ± 0.07 b | 0.48 ± 0.09 ab | 323.70 ± 2.54 cd |

| SN9714 | 9.13 ± 2.23 a | 2.11 ± 0.19 a | 5.95 ± 1.13 b | 2.39 ± 0.33 ab | 5.16 ± 0.28 a | 3.75 ± 0.81 a | 8.72 ± 1.39 b | 0.34 ± 0.12 b | 364.21 ± 16.91 bc |

| CJN6 | 10.3 ± 0.01 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 6.12 ± 0.00 b | 2.89 ± 0.00 a | 8.15 ± 0.00 a | 1.72 ± 0.00 ab | 8.19 ± 0.00 b | 0.35 ± 0.00 b | 406.31 ± 29.96 ab |

| ZN106 | 8.47 ± 0.18 a | 1.12 ± 1.00 ab | 7.49 ± 1.57 ab | 1.27 ± 1.21 bc | 7.74 ± 1.22 a | 1.35 ± 1.33 b | 8.94 ± 0.47 b | 0.39 ± 0.02 ab | 396.55 ± 0.22 ab |

| ZN65 | 9.88 ± 0.60 a | 1.57 ± 1.05 a | 6.46 ± 0.60 b | 3.08 ± 0.49 a | 9.20 ± 1.12 a | 1.81 ± 0.83 ab | 8.05 ± 0.76 b | 0.38 ± 0.02 ab | 427.61 ± 11.82 a |

| THN | 8.64 ± 1.27 a | 2.31 ± 0.31 a | 6.86 ± 1.12 ab | 1.81 ± 0.04 ab | 10.51 ± 7.21 a | 1.44 ± 2.04 b | 8.02 ± 1.53 b | 0.13 ± 0.17 b | 366.83 ± 28.93 b |

| WGN1 | 9.09 ± 0.27 a | 1.53 ± 0.55 a | 6.96 ± 0.57 ab | 2.53 ± 0.93 ab | 10.04 ± 0.65 a | 1.47 ± 0.37 b | 9.72 ± 1.67 b | 0.33 ± 0.02 b | 379.59 ± 17.85 b |

| YN12 | 8.29 ± 0.00 a | 1.85 ± 0.00 a | 8.44 ± 0.01 a | 0.37 ± 0.00 c | 9.77 ± 0.01 a | 1.38 ± 0.03 b | 14.50 ± 0.03 a | 0.55 ± 0.00 a | 382.84 ± 10.13 b |

| Varieties | XRD | SAXS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rc (%) | Imax | Smax × 10−3 | ∆S × 10−4 | D (nm) | |

| NGXN | 22.83 ± 1.19 a | 558.58 | 68.00 | 195.10 | 9.24 |

| ZN19 | 20.83 ± 1.38 ab | 363.30 | 66.91 | 235.10 | 9.38 |

| GMN2 | 19.76 ±1.06 b | 496.93 | 70.89 | 197.50 | 8.86 |

| SN9714 | 20.14 ±1.01 b | 244.44 | 71.37 | 215.60 | 8.80 |

| CJN6 | 19.29 ±1.30 b | 492.92 | 69.08 | 201.20 | 9.09 |

| ZN106 | 20.80 ± 1.08 ab | 395.95 | 68.36 | 180.72 | 9.19 |

| ZN65 | 21.06 ± 1.41 ab | 456.56 | 68.96 | 203.60 | 9.11 |

| THN | 21.39 ± 0.84 ab | 500.00 | 68.24 | 197.59 | 9.20 |

| WGN1 | 21.24 ± 1.61 ab | 470.70 | 68.36 | 207.20 | 9.19 |

| YN12 | 21.28 ± 1.08 ab | 542.00 | 69.92 | 203.61 | 8.98 |

| Varieties | PV (cP) | TV (cP) | BDV (cP) | FV (cP) | SV (cP) | PT (min) | PT (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGXN | 2261 ± 31 h | 1473 ± 21 d | 788 ± 13 i | 1714 ± 5 ef | 241 ± 11 g | 3.91 ± 0.03 e | 72.80 ± 0.10 d |

| ZN19 | 2415 ± 31 g | 1458 ± 27 d | 957 ± 21 g | 1730 ± 9 e | 272 ± 8 de | 3.93 ± 0.04 e | 72.50 ± 0.21 de |

| GMN2 | 2842 ± 36 c | 1795 ± 25 bc | 1047 ± 11 f | 2587 ± 6 a | 792 ± 11 a | 4.33 ± 0.04 a | 74.10 ± 0.15 b |

| SN9714 | 2752 ± 46 d | 1345 ± 25 f | 1407 ± 13 a | 1607 ± 7 i | 262 ± 5 ef | 3.67 ± 0.01 h | 70.95 ± 0.04 g |

| CJN6 | 2541 ± 39 ef | 1403 ± 25 e | 1138 ± 9 e | 1669 ± 11 g | 266 ± 7 e | 3.53 ± 0.02 i | 71.20 ± 0.15 g |

| ZN106 | 3130 ± 16 b | 1833 ± 11 a | 1297 ± 6 d | 2165 ± 11 b | 332 ± 6 b | 4.07 ± 0.02 c | 71.55 ± 0.33 f |

| ZN65 | 2643 ± 34 e | 1310 ± 15 g | 1333 ± 14 c | 1635 ± 10 h | 325 ± 6 bc | 3.73 ± 0.01 g | 71.70 ± 0.21 f |

| THN | 2134 ± 26 i | 1171 ± 14 h | 963 ± 7 h | 1375 ± 7 j | 204 ± 3 h | 3.80 ± 0.02 f | 72.45 ± 0.20 e |

| WGN1 | 3205 ± 26 a | 1826 ± 9 ab | 1379 ± 19 b | 2138 ± 11 c | 312 ± 14 c | 4.00 ± 0.03 d | 73.35 ± 0.15 c |

| YN12 | 2519 ± 29 ef | 1771 ± 16 c | 748 ± 10 j | 2053 ± 7 d | 282 ± 6 d | 4.27 ± 0.02 b | 74.90 ± 0.08 a |

| Varieties | Gelatinization | Retrogradation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To (°C) | Tp (°C) | Tc (°C) | ΔH (J/g) | To (°C) | Tp (°C) | Tc (°C) | ΔH (J/g) | |

| NGXN | 62.8 ± 1.6 d | 70.3 ± 0.3 d | 78.4 ± 0.4 cd | 14.8 ± 0.3 a | 63.4 ± 0.4 b | 65.1 ± 0.3 b | 69.0 ± 0.5 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 d |

| ZN19 | 64.7 ± 0.7 bc | 71.1 ± 0.4 c | 78.9 ± 0.5 bc | 12.7 ± 0.2 d | 65.1 ± 0.3 a | 66.9 ± 0.4 a | 69.2 ± 0.3 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 b |

| GMN2 | 65.7 ± 0.5 ab | 72.2 ± 0.3 a | 79.4 ± 0.4 b | 12.6 ± 0.2 de | 47.8 ± 0.3 f | 57.0 ± 0.5 d | 59.0 ± 0.3 b | 0.3 ± 0.0 a |

| SN9714 | 62.7 ± 0.6 d | 70.1 ± 0.4 d | 77.9 ± 0.3 de | 12.3 ± 0.2 e | 57.7 ± 0.4 c | 56.1 ± 0.3 e | 57.6 ± 0.4 de | 0.1 ± 0.0 f |

| CJN6 | 60.2 ± 0.0 e | 68.2 ± 0.3 e | 77.4 ± 0.3 e | 12.8 ± 0.2 d | 46.9 ± 0.7 g | 49.8 ± 0.4 h | 57.0 ± 0.4 e | 0.1 ± 0.0 i |

| ZN106 | 63.2 ± 0.8 d | 69.9 ± 0.3 d | 77.4 ± 0.4 e | 12.6 ± 0.2 de | 52.9 ± 0.6 d | 54.6 ± 0.5 f | 57.4 ± 0.4 e | 0.1 ± 0.0 g |

| ZN65 | 63.5 ± 0.5 cd | 71.6 ± 0.3 bc | 79.4 ± 0.3 b | 13.0 ± 0.2 d | 64.4 ± 0.6 a | 67.3 ± 0.5 a | 68.9 ± 0.2 a | 0.1 ± 0.0 h |

| THN | 65.3 ± 0.6 ab | 72.0 ± 0.2 ab | 79.1 ± 0.2 b | 13.9 ± 0.2 b | 50.0 ± 0.6 e | 52.6 ± 0.5 g | 59.1 ± 0.3 b | 0.1 ± 0.0 e |

| WGN1 | 65.6 ± 0.5 ab | 71.6 ± 0.4 bc | 79.8 ± 0.3 b | 13.4 ± 0.3 c | 52.2 ± 0.5 d | 56.7 ± 0.4 de | 58.2 ± 0.3 cd | 0.2 ± 0.0 d |

| YN12 | 66.4 ± 0.4 a | 72.0 ± 0.2 ab | 80.8 ± 0.5 a | 13.5 ± 0.2 c | 49.4 ± 0.3 e | 57.7 ± 0.4 c | 58.7 ± 0.4 bc | 0.2 ± 0.0 c |

| Samples | Log | |

|---|---|---|

| k 10−2 (min−1) | Cres (%) | |

| NGXN | 1.54 ± 0.08 d | 5.63 ± 0.11 d |

| ZN19 | 1.71 ± 0.04 c | 9.06 ± 0.04 b |

| GMN2 | 1.47 ± 0.03 e | 4.58 ± 0.03 f |

| SN9714 | 1.74 ± 0.03 bc | 3.97 ± 0.03 i |

| CJN6 | 1.79 ± 0.02 b | 5.20 ± 0.02 e |

| ZN106 | 1.90 ± 0.02 a | 8.66 ± 0.02 c |

| ZN65 | 1.72 ± 0.02 c | 4.38 ± 0.02 h |

| THN | 1.60 ± 0.02 d | 4.49 ± 0.03 g |

| WGN1 | 1.55 ± 0.03 d | 1.16 ± 0.02 j |

| YN12 | 1.48 ± 0.02 e | 9.81 ± 0.03 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaman, W.u.; Ijaz, Z.; Nadeem, M.Y.; Ahmed, S.; Li, E. Investigating the Impact of Amylopectin Chain-Length Distribution on the Structural and Functional Properties of Waxy Rice Starch. Foods 2025, 14, 4130. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234130

Zaman Wu, Ijaz Z, Nadeem MY, Ahmed S, Li E. Investigating the Impact of Amylopectin Chain-Length Distribution on the Structural and Functional Properties of Waxy Rice Starch. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4130. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234130

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaman, Waqar ul, Zainab Ijaz, Muhammad Yousaf Nadeem, Shibbir Ahmed, and Enpeng Li. 2025. "Investigating the Impact of Amylopectin Chain-Length Distribution on the Structural and Functional Properties of Waxy Rice Starch" Foods 14, no. 23: 4130. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234130

APA StyleZaman, W. u., Ijaz, Z., Nadeem, M. Y., Ahmed, S., & Li, E. (2025). Investigating the Impact of Amylopectin Chain-Length Distribution on the Structural and Functional Properties of Waxy Rice Starch. Foods, 14(23), 4130. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234130