Blanching of Two Commercial Norwegian Brown Algae for Reduction of Iodine and Other Compounds of Importance for Food Safety and Quality †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Blanching Methods and Conditions

2.3. Chemical Analysis

2.3.1. Sample Preparation

2.3.2. Dry Matter and Ash

2.3.3. Iodine, Inorganic Arsenic, and Other Minerals and Trace Elements

2.3.4. Lipids

2.3.5. Free and Total Amino Acids

2.3.6. Carbohydrates

2.3.7. Water-Soluble Vitamins (Vitamin C and Folate)

2.4. Microbial Counts

2.5. Data Presentation and Statistics

3. Results and Discussion

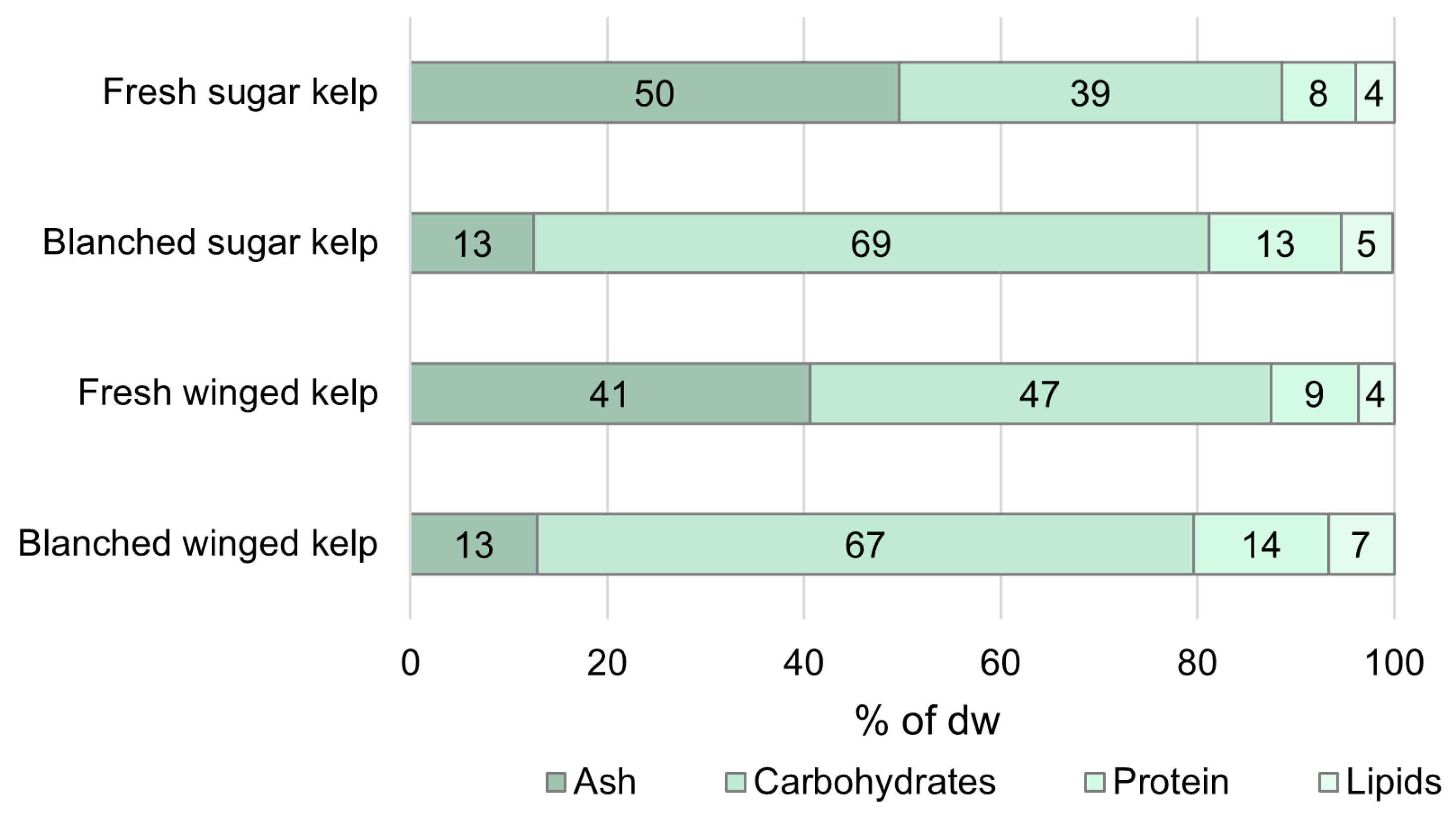

3.1. Proximate Composition of Fresh and Blanched Biomass

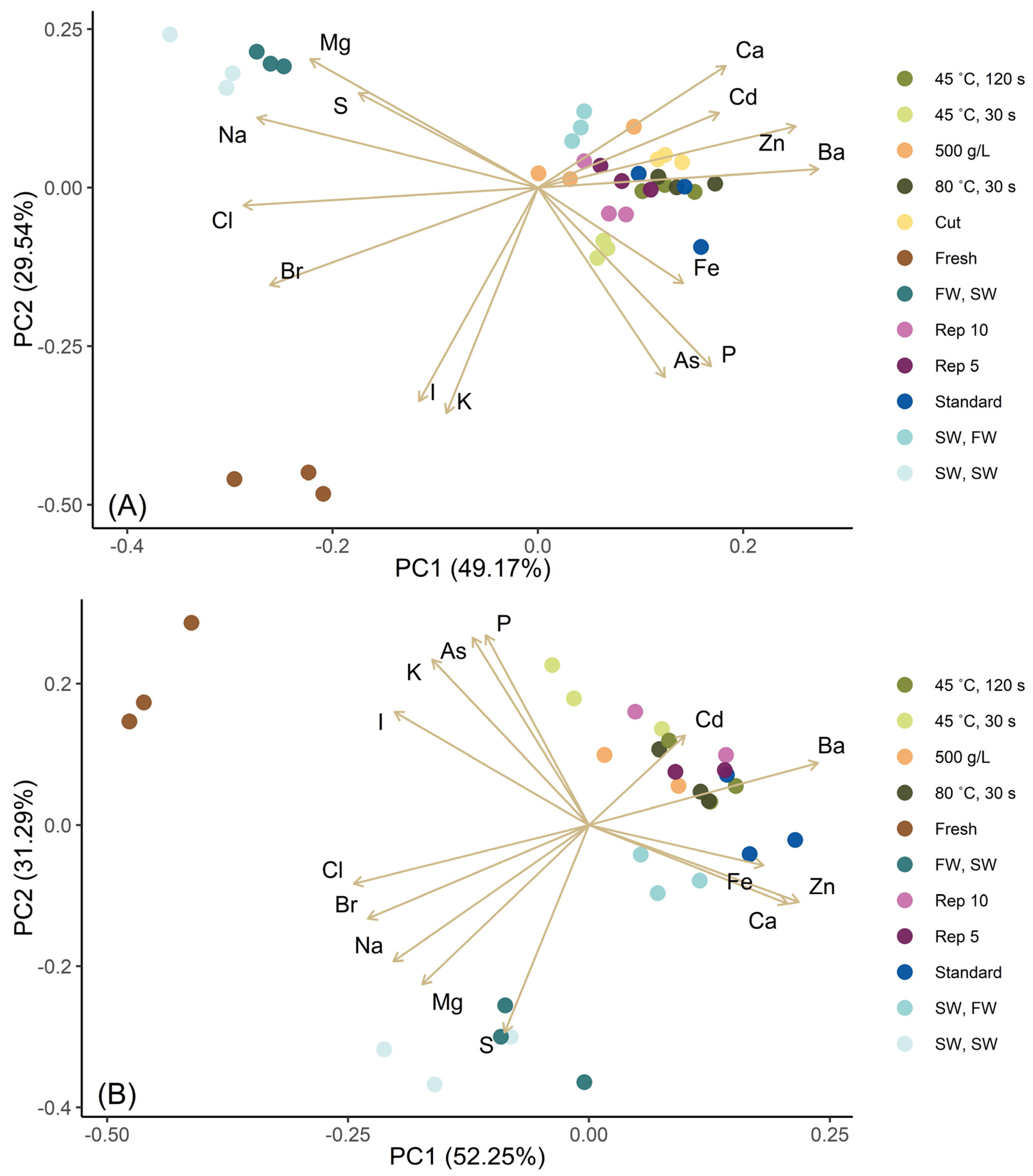

3.2. Reduction of Minerals and Trace Elements by Blanching at Different Conditions

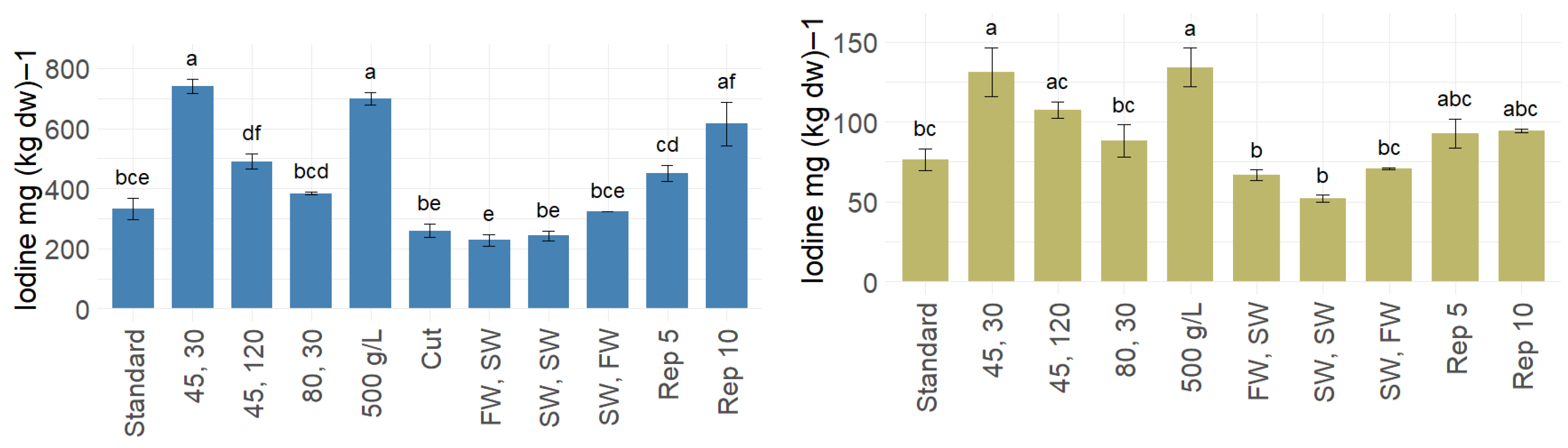

3.3. Iodine Reduction, Blanching Water Recycling, and Allowable Seaweed Consumption Levels

3.4. The Possibility of Lowering the Potentially Toxic Elements, Arsenic and Cadmium, Using Various Blanching Conditions

3.5. Loss of Flavor Compounds and Nutrients

3.6. The Effect of Blanching on the Soluble Carbohydrates of the Biomass

3.7. The Decrease in Microbial Load

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries. Akvakulturstatistikk: Andre Arter. Available online: https://www.fiskeridir.no/Akvakultur/Tall-og-analyse/Akvakulturstatistikk-tidsserier/Alger (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Küpper, F.C.; Carpenter, L.J.; McFiggans, G.B.; Palmer, C.J.; Waite, T.J.; Boneberg, E.M.; Woitsch, S.; Weiller, M.; Abela, R.; Grolimund, D.; et al. Iodide accumulation provides kelp with an inorganic antioxidant impacting atmospheric chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 6954–6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO Expert Consultation. Human Vitamin and Mineral Requirements; Food and Nutrition Division, FAO: Rome, Italy, 2001; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42716 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- EFSA. Overview on Tolerable Upper Intake Levels as Derived by the Scientific Committee on Food (SCF) and the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA); European Food Safety Authorities: Parma, Italy, 2018. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/assets/UL_Summary_tables.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Küpper, F.C.; Schweigert, N.; Ar Gall, E.; Legendre, J.M.; Vilter, H.; Kloareg, B. Iodine uptake in Laminariales involves extracellular, haloperoxidase-mediated oxidation of iodide. Planta 1998, 207, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreissig, K.J.; Hansen, L.T.; Jensen, P.E.; Wegeberg, S.; Geertz, O.H.; Sloth, J.J. Characterisation and chemometric evaluation of 17 elements in ten seaweed species from Greenland. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0243672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, C.W.; Holdt, S.L.; Sloth, J.J.; Marinho, G.S.; Sæther, M.; Funderud, J.; Rustad, T. Reducing the High Iodine Content of Saccharina latissima and Improving the Profile of Other Valuable Compounds by Water Blanching. Foods 2020, 9, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roleda, M.Y.; Skjermo, J.; Marfaing, H.; Jónsdóttir, R.; Rebours, C.; Gietl, A.; Stengel, D.B.; Nitschke, U. Iodine content in bulk biomass of wild-harvested and cultivated edible seaweeds: Inherent variations determine species-specific daily allowable consumption. Food Chem. 2018, 254, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stévant, P.; Marfaing, H.; Duinker, A.; Fleurence, J.; Rustad, T.; Sandbakken, I.; Chapman, A. Biomass soaking treatments to reduce potentially undesirable compounds in the edible seaweeds sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima) and winged kelp (Alaria esculenta) and health risk estimation for human consumption. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 2047–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlov, Ø.; Nøkling-Eide, K.; Aarstad, O.A.; Jacobsen, S.S.; Langeng, A.-M.; Borrero, A.; Sæther, M.; Rustad, T.; Aachmann, F.L.; Sletta, H. Variations in chemical composition of Norwegian cultivated brown algae Saccharina latissima and Alaria esculenta based on deployment and harvest times. Algal Res. 2024, 78, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, J.L.; Hoek-van den Hil, E.F.; van der Fels-Klerx, H.J. Food safety hazards in the European seaweed chain. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 332–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballance, S.; Rieder, A.; Arlov, Ø.; Knutsen, S.H. Brown seaweed as a food ingredient contributing to an adequate but not excessive amount of iodine in the European diet. A case study with bread. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 8897–8906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Kim, J.; Noh, C.H.; Choi, S.; Joo, Y.S.; Lee, K.W. Monitoring arsenic species content in seaweeds produced off the southern coast of Korea and its risk assessment. Environments 2020, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, A.; Smidsrød, O. The Effect of Divalent Metals on the Properties of Alginate Solutions. II. Comparison of Different Metal Ions. Acta Chem. Scand. 1965, 19, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, S.S.; Wakayama, M.; Ashino, Y.; Kadowaki, R.; Soga, T.; Tomita, M. Effect of blanching on the concentration of metabolites in two parts of Undaria pinnatifida, Wakame (leaf) and Mekabu (sporophyll). Algal Res. 2020, 47, 101829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.W.; Pan, Z.; Deng, L.Z.; El-Mashad, H.M.; Yang, X.H.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Gao, Z.J.; Zhang, Q. Recent developments and trends in thermal blanching—A comprehensive review. Inform. Proc. Agric. 2017, 4, 101–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, M.; Nordberg Karlsson, E. Chemical food safety of seaweed: Species, spatial and thallus dependent variation of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) and techniques for their removal. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blikra, M.J.; Henjum, S.; Aakre, I. Iodine from brown algae in human nutrition, with an emphasis on bioaccessibility, bioavailability, chemistry, and effects of processing: A systematic review. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 1517–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, A.; Brynning, G.; Johansen, A.; Lindegaard, M.S.; Sveigaard, H.H.; Aarup, B.; Fonager, L.; Andersen, L.L.; Rasmussen, M.B.; Larsen, M.M.; et al. Fermentation of sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima)—Effects on sensory properties, and content of minerals and metals. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 3175–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, U.; Stengel, D.B. Quantification of iodine loss in edible Irish seaweeds during processing. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 3527–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blikra, M.J.; Rode, T.M.; Skåra, T.; Maribu, I.; Sund, R.; Vaka, M.R.; Skipnes, D. Processing of sugar kelp: Effects on mass balance, nutrient composition, and color. LWT 2024, 203, 116402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC Method 950.46 Official Methods of Analysis (Issue 15); Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 1990.

- Yu, L.L.; Butler, T.A.; Turk, G.C. Effect of valence state on ICP-OES value assignment of SRM 3103a arsenic spectrometric solution. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 1651–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stévant, P.; Indergård, E.; Ólafsdóttir, A.; Marfaing, H.; Larssen, W.E.; Fleurence, J.; Roleda, M.Y.; Rustad, T.; Slizyte, R.; Nordtvedt, T.S. Effects of drying on the nutrient content and physico-chemical and sensory characteristics of the edible kelp Saccharina latissima. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 2587–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osnes, K.K.; Mohr, V. Peptide Hydrolases of Antarctic Krill, Euphausia superba. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1985, 82, 599–606. [Google Scholar]

- Wirenfeldt, C.B.; Sørensen, J.S.; Kreissig, K.J.; Hyldig, G.; Holdt, S.L.; Hansen, L.T. Post-harvest quality changes and shelf-life determination of washed and blanched sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima). Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 1030229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ložnjak Švarc, P.; Oveland, E.; Strandler, H.S.; Kariluoto, S.; Campos-Giménez, E.; Ivarsen, E.; Malaviole, I.; Motta, C.; Rychlik, M.; Striegel, L.; et al. Collaborative study: Quantification of total folate in food using an efficient single-enzyme extraction combined with LC-MS/MS. Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NMKL Method 184, Aerobic Count and Specific Spoilage Organisms in Fish and Fish Products. Nordic Committee on Food Analysis. 2006. Available online: https://www.nmkl.org/product/aerobic-count-and-specific-spoilage-organisms-in-fish-and-fish-products/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- R-Core-Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2022. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Wright, J.; Colling, A. Seawater: Its Composition, Properties and Behaviour; Pergamon/Elsevier Walton Hall: Milton Keyes, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AFSSA. Opinion of the French Food Safety Agency on the Recommended Maximum Inorganic Arsenic Content of Laminaria and Consumption of These Seaweeds in Light of Their High Iodine Content. 2009. Available online: https://www.anses.fr/en/system/files/RCCP2007sa0007EN.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on Arsenic in Food. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blikra, M.J.; Wang, X.; James, P.; Skipnes, D. Saccharina latissima cultivated in Northern Norway: Reduction of potentially toxic elements during processing in relation to cultivation depth. Foods 2021, 10, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norsk Lovtidend. Forskrift om Endring i Fôrvareforskriften. 2020. Available online: https://lovdata.no/LTI/forskrift/2020-06-25-1515 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Sá Monteiro, M.; Sloth, J.; Holdt, S.; Hansen, M. Analysis and Risk Assessment of Seaweed. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e170915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pétursdóttir, Á.H.; Blagden, J.; Gunnarsson, K.; Raab, A.; Stengel, D.B.; Feldmann, J.; Gunnlaugsdóttir, H. Arsenolipids are not uniformly distributed within two brown macroalgal species Saccharina latissima and Alaria esculenta. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019, 411, 4973–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2019/1869, Official Journal of the European Union 8.11.2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1869/oj (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Mouritsen, O.G.; Williams, L.; Bjerregaard, R.; Duelund, L. Seaweeds for umami flavour in the New Nordic Cuisine. Flavour 2012, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delchier, N.; Herbig, A.L.; Rychlik, M.; Renard, C.M.G.C. Folates in Fruits and Vegetables: Contents, Processing, and Stability. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 506–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, C.W.; Rustad, T.; Holdt, S.L. Vitamin C from seaweed: A review assessing seaweed as contributor to daily intake. Foods 2021, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for folate. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Bernaldo De Quirós, A.; Castro De Ron, C.; López-Hernández, J.; Lage-Yusty, M.A. Determination of folates in seaweeds by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chrom. A 2004, 1032, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiger-Pouvreau, V.; Bourgougnon, N.; Deslandes, E. Carbohydrates from Seaweeds. In Seaweed in Health and Disease Prevention; Academic Press/Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, C.; Sørensen, A.-D.M.; Holdt, S.L.; Akoh, C.C.; Hermund, D.B. Source, extraction, characterization, and applications of novel antioxidants from seaweed. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 541–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birgersson, P.S.; Oftebro, M.; Strand, W.I.; Aarstad, O.A.; Sætrom, G.I.; Sletta, H.; Arlov, Ø.; Aachmann, F.L. Sequential extraction and fractionation of four polysaccharides from cultivated brown algae Saccharina latissima and Alaria esculenta. Algal Res. 2023, 69, 102928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blikra, M.J.; Løvdal, T.; Vaka, M.R.; Roiha, I.S.; Lunestad, B.T.; Lindseth, C.; Skipnes, D. Assessment of food quality and microbial safety of brown macroalgae (Alaria esculenta and Saccharina latissima). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Set-Up | Abbreviation for Condition | Seaweed-to-Water Ratio (g ww) L−1 | Blade | Blanching Water, Cooling Water | Temp (°C), Duration (s) | Number of Blanchings in Same Water | Reuse of Water | Experimental Replicates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugar Kelp | Winged Kelp | ||||||||

| Standard | Standard | 50 | whole | FW, FW | 80, 120 | 1 | No | n = 3 | n = 3 |

| Exp. 1 | 45 °C, 30 s 45 °C, 120 s 80 °C, 30 s | 50 | whole | FW, FW | 45, 30 45, 120 80, 30 | 1 | No | n

= 3

n = 3 n = 3 | n

= 3

n = 3 n = 3 |

| Exp. 2 | 500 g/L | 500 | whole | FW, FW | 80, 120 | 1 | No | n = 3 | n = 2 |

| Exp. 3 | Cut | 50 | cut | FW, FW | 80, 120 | 1 | No | n = 3 | - |

| Exp. 4 | FW, SW SW, SW SW, FW | 50 | whole | FW, SW SW, SW SW, FW | 80, 120 | 1 | No | n

= 3

n = 3 n = 3 | n

= 3

n = 3 n = 3 |

| Exp. 5 | Rep X | 50 | whole | FW, FW | 80, 120 | 1–10 | Yes, up to 9 times | n = 3 | n = 2 |

| Blanching Conditions | S. latissima | A. esculenta | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Weight [% of ww] | Ash [% of dw] | Protein [% of dw] | Dry Weight [% of ww] | Ash [% of dw] | Protein [% of dw] | |

| Standard | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 12.5 ± 1.3 | 13.4 ± 1.2 | 7.2 ± 0.84 | 12.9 ± 0.46 | 13.7 ± 1.5 |

| 45 °C, 30 s | 6.6 ± 0.84 | 16.5 ± 1.1 | 12.0 ± 0.05 | 8.9 ± 1.2 | 18.7 ± 3.5 | 11.5 ± 0.93 |

| 45 °C, 120 s | 5.2 ± 1.1 | 13.3 ± 1.3 | 14.3 ± 0.19 | 9.9 ± 1.3 | 16.4 ± 2.8 | 12.4 ± 1.1 |

| 80°, 30 s | 5.3 ± 0.75 | 13.9 ± 1.7 | 13.1 ± 0.55 | 9.9 ± 2.1 | 13.8 ± 1.2 | 12.3 ± 1.6 |

| FW, SW | 8.0 ± 0.63 | 39.9 ± 2.9 | - | 11.7 ± 1.1 | 28.1 ± 2.1 | - |

| SW, SW | 9.6 ± 1.4 | 41.9 ± 3.7 | 7.2 ± 0.33 | 13.3 ± 1.4 | 31.8 ± 3.7 | 8.8 ± 0.44 |

| SW, FW | 6.7 ± 1.0 | 17.8 ± 3.2 | - | 10.8 ± 1.6 | 16.3 ± 1.7 | 13.2 ± 0.54 |

| Blanching Conditions—S. latissima | ||||||||

| Minerals | Fresh | Standard | 45 °C, 30 s | 45 °C, 120 s | 80 °C, 30 s | FW, SW | SW, SW | SW, FW |

| I [mg/kg dw] | 4818 ± 405 | 331 ± 61 | 741 ± 41 | 490 ± 44 | 384 ± 8 | 228 ± 34 | 243 ± 28 | 324 ± 2 |

| As [mg/kg dw] | 67 ± 13 | 63 ± 4.0 | 68 ± 2.2 | 60 ± 2.5 | 65 ± 1.5 | 40 ± 1.6 | 40 ± 4.3 | 54 ± 4.5 |

| Cd [mg/kg dw] | 0.8 ± 0.25 | 1.3 ± 0.14 | 1.1 ± 0.08 | 1.2 ± 0.11 | 1.4 ± 0.05 | 1.1 ± 0.11 | 1.0 ± 0.08 | 1.6 ± 0.10 |

| Br [mg/kg dw] | 1768 ± 360 | 297 ± 27 | 593 ± 17 | 428 ± 16 | 383 ± 1 | 1072 ± 37 | 1173 ± 39 | 628 ± 25 |

| Na [g/kg dw] | 53 ± 1.8 | 11 ± 1.7 | 11 ± 0.95 | 10 ± 0.20 | 11 ± 0.89 | 103 ± 5.1 | 111 ± 11 | 40 ± 0.85 |

| K [g/kg dw] | 143 ± 50 | 30 ± 9.7 | 50 ± 4.1 | 34 ± 3.0 | 34 ± 2.3 | 18 ± 3.2 | 18 ± 2.6 | 17 ± 1.9 |

| Cl [g/kg dw] | 232 ± 50 | 12 ± 9.3 | 32 ± 4.0 | 11 ± 1.4 | 15 ± 2.2 | 219 ± 11 | 240 ± 19 | 68 ± 4.9 |

| Ca [g/kg dw] | 9.1 ± 0.12 | 13 ± 0.77 | 12 ± 0.42 | 14 ± 0.17 | 14 ± 0.56 | 12 ± 0.71 | 12 ± 0.38 | 14 ± 0.70 |

| Mg [g/kg dw] | 8.5 ± 0.23 | 8.5 ± 0.48 | 7.1 ± 0.36 | 8.3 ± 0.29 | 8.7 ± 0.49 | 15 ± 0.68 | 17 ± 1.2 | 12 ± 0.11 |

| P [g/kg dw] | 3.2 ± 0.65 | 3 ± 0.19 | 2.8 ± 0.11 | 2.9 ± 0.07 | 3 ± 0.11 | 1.8 ± 0.09 | 1.8 ± 0.16 | 2.7 ± 0.09 |

| S [g/kg dw] | 8.4 ± 0.59 | 9.3 ± 0.62 | 9.9 ± 0.42 | 11 ± 0.20 | 10 ± 0.53 | 12 ± 0.52 | 13 ± 0.99 | 11 ± 0.23 |

| Fe [mg/kg dw] | 56 ± 1.4 | 100 ± 41 | 85 ± 5.7 | 106 ± 11 | 76 ± 5.5 | 40 ± 4.0 | 52 ± 9.3 | 92 ± 17 |

| Zn [mg/kg dw] | 26 ± 4.6 | 45 ± 6.7 | 42 ± 3.5 | 47 ± 3.1 | 53 ± 4.3 | 35 ± 2.5 | 32 ± 2.9 | 50 ± 2.9 |

| Blanching Conditions—A. esculenta | ||||||||

| Minerals | Fresh | Standard | 45 °C, 30 s | 45 °C, 120 s | 80 °C, 30 s | FW, SW | SW, SW | SW, FW |

| I [mg/kg dw] | 682 ± 120 | 76 ± 12 | 131 ± 26 | 108 ± 9.0 | 88 ± 18 | 67 ± 5.8 | 52 ± 3.5 | 71 ± 1.1 |

| As [mg/kg dw] | 48 ± 3.3 | 27 ± 0.96 | 33 ± 2.4 | 28 ± 1.9 | 31 ± 2.3 | 21 ± 0.95 | 20 ± 1.0 | 27 ± 1.4 |

| Cd [mg/kg dw] | 2.1 ± 0.05 | 2.3 ± 0.49 | 2.7 ± 0.10 | 2.8 ± 0.45 | 2.2 ± 0.18 | 1.8 ± 0.14 | 2.2 ± 0.76 | 2.6 ± 0.12 |

| Br [mg/kg dw] | 886 ± 110 | 117 ± 9.3 | 195 ± 25 | 164 ± 25 | 147 ± 38 | 657 ± 49 | 741 ± 54 | 256 ± 25 |

| Na [g/kg dw] | 77 ± 9.3 | 8.3 ± 1.7 | 14 ± 2.3 | 11 ± 0.37 | 12 ± 2.2 | 76 ± 2.7 | 88 ± 3.6 | 33 ± 1.9 |

| K [g/kg dw] | 94 ± 4.0 | 20 ± 6.1 | 60 ± 13 | 38 ± 5.4 | 36 ± 6.5 | 14 ± 4.8 | 13 ± 1.8 | 15 ± 3.7 |

| Cl [g/kg dw] | 251 ± 34 | 11 ± 5.1 | 62 ± 13 | 31 ± 6.5 | 31 ± 9.9 | 145 ± 5.9 | 174 ± 18 | 52 ± 6.2 |

| Ca [g/kg dw] | 10 ± 0.78 | 14 ± 0.41 | 12 ± 0.28 | 14 ± 0.76 | 13 ± 0.52 | 13 ± 0.51 | 12 ± 0.83 | 13 ± 0.30 |

| Mg [g/kg dw] | 12 ± 0.96 | 8.7 ± 0.38 | 7.4 ± 0.10 | 7.9 ± 0.27 | 8.1 ± 0.32 | 12 ± 0.06 | 13 ± 0.49 | 10 ± 0.23 |

| P [g/kg dw] | 4.3 ± 0.28 | 3.0 ± 0.07 | 3.1 ± 0.31 | 3.0 ± 0.13 | 3.1 ± 0.07 | 2.3 ± 0.10 | 2.2 ± 0.11 | 3.0 ± 0.09 |

| S [g/kg dw] | 9.4 ± 0.29 | 8.8 ± 0.69 | 8.1 ± 0.53 | 9.0 ± 0.28 | 8.9 ± 0.22 | 12 ± 0.45 | 12 ± 0.55 | 9.7 ± 0.17 |

| Fe [mg/kg dw] | 95 ± 15 | 147 ± 24 | 122 ± 9.3 | 132 ± 18 | 140 ± 2.5 | 139 ± 19 | 106 ± 19 | 140 ± 13 |

| Zn [mg/kg dw] | 39 ± 2.4 | 80 ± 11 | 60 ± 9.7 | 72 ± 5.6 | 74 ± 3.7 | 72 ± 12 | 64 ± 7.2 | 80 ± 6.3 |

| Vitamin C (1); | Total Folate (1) | Free Aspartic Acid | Free Glutamic Acid | Potassium | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg (g dw)−1 | µg (g dw)−1 | mg (g dw)−1 | mg (g dw)−1 | mg (g dw)−1 | |

| Sugar kelp | |||||

| Fresh | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 2.19 ± 0.20 | 1.68 ± 0.49 | 1.16 ± 0.40 | 143 ± 50 |

| Standard blanched | <LOQ | 1.05 ± 0.014 | 0.261 ± 0.105 | 0.334 ± 0.169 | 30.0 ± 9.7 |

| Loss [%] | - | 52 | 84 | 71 | 79 |

| Winged kelp | |||||

| Fresh | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 9.27 ± 3.8 | 1.02 ± 0.35 | 1.14 ± 0.12 | 93.9 ± 4.0 |

| Standard blanched | <LOQ | 2.31 ± 1.09 | 0.142 ± 0.094 | 0.359 ± 0.137 | 19.8 ± 6.1 |

| Loss [%] | - | 75 | 86 | 68 | 79 |

| Content in the Fresh Biomass (% of dw) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fucose | Glucose | Mannitol | |

| Sugar kelp | 0.93 ± 0.18 | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 7.7 ± 6.3 |

| Winged kelp | 1.02 ± 0.07 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.1 |

| Content in the Blanching Water (mg L−1) | |||

| Fucose | Glucose | Mannitol | |

| Sugar kelp | |||

| Standard | 26.6 ± 2.6 | 1.88 ± 0.61 | 140 ± 6 |

| 45 °C, 30 s | 6.59 ± 0.69 | 0.926 ± 0.123 | 11.9 ± 9.5 |

| Cut | 90.5 ± 6.7 | 2.68 ± 0.81 | 42.9 ± 29.2 |

| SW, SW | 0.933 ± 0.077 | 0.337 ± 0.089 | 9.32 ± 1.31 |

| Rep 5 | 128 ± 81 | 48.5 ± 61.3 | 764 ± 644 |

| Rep 10 | 296 ± 127 | 155 ± 127 | 2010 ± 1160 |

| Winged kelp | |||

| Standard | 6.37 ± 0.51 * | 0.666 ± 0.002 * | 112 ± 0 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sletta, M.S.; Wirenfeldt, C.B.; Sæther, M.; Arlov, Ø.; Švarc, P.L.; Jacobsen, S.S.; Aachmann, F.L.; Sletta, H.; Holdt, S.L.; Aasen, I.M.; et al. Blanching of Two Commercial Norwegian Brown Algae for Reduction of Iodine and Other Compounds of Importance for Food Safety and Quality. Foods 2025, 14, 4113. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234113

Sletta MS, Wirenfeldt CB, Sæther M, Arlov Ø, Švarc PL, Jacobsen SS, Aachmann FL, Sletta H, Holdt SL, Aasen IM, et al. Blanching of Two Commercial Norwegian Brown Algae for Reduction of Iodine and Other Compounds of Importance for Food Safety and Quality. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4113. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234113

Chicago/Turabian StyleSletta, Maria Stavnes, Cecilie Bay Wirenfeldt, Maren Sæther, Øystein Arlov, Petra Ložnjak Švarc, Synnøve Strand Jacobsen, Finn Lillelund Aachmann, Håvard Sletta, Susan Løvstad Holdt, Inga Marie Aasen, and et al. 2025. "Blanching of Two Commercial Norwegian Brown Algae for Reduction of Iodine and Other Compounds of Importance for Food Safety and Quality" Foods 14, no. 23: 4113. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234113

APA StyleSletta, M. S., Wirenfeldt, C. B., Sæther, M., Arlov, Ø., Švarc, P. L., Jacobsen, S. S., Aachmann, F. L., Sletta, H., Holdt, S. L., Aasen, I. M., & Rustad, T. (2025). Blanching of Two Commercial Norwegian Brown Algae for Reduction of Iodine and Other Compounds of Importance for Food Safety and Quality. Foods, 14(23), 4113. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234113