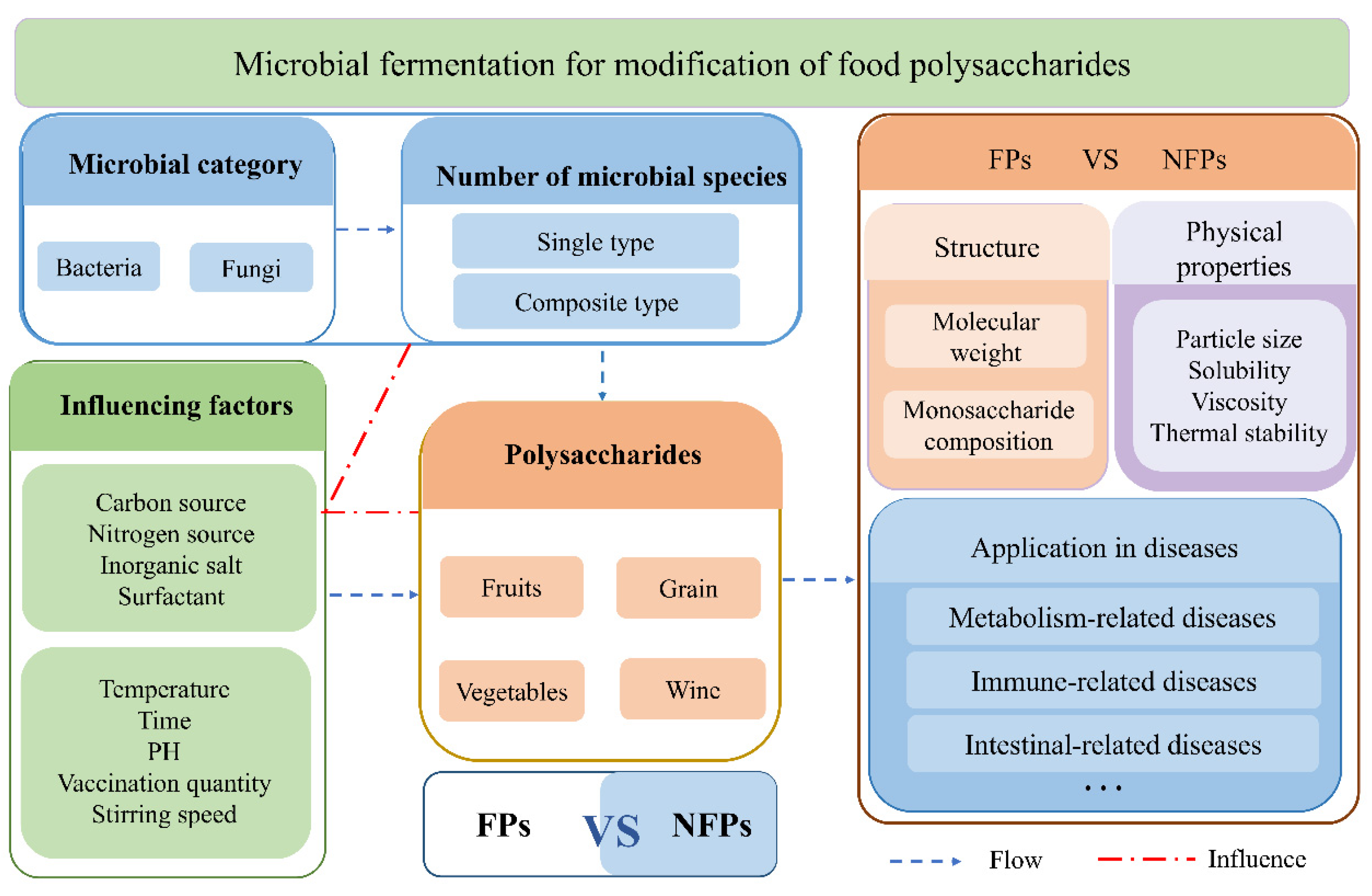

Fermented Food–Polysaccharides as Gut Health Regulators: Sources, Optimization, Structural Characteristics and Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Source

2.1. Bacterial Fermentation Food–Polysaccharides

2.2. Fungal Fermentation Food–Polysaccharides

3. Optimization of Fermentation Conditions

3.1. Optimization of Culture Medium Components

3.2. Optimization of Fermentation Conditions

3.3. Methodology of Condition Optimization and Fermentation Amplification Strategy

4. The Effect of Fermentation on Structure and Physical Properties of Food–Polysaccharides

4.1. Effect of Fermentation on Molecular Weight of Polysaccharides

4.2. Monosaccharide Composition

4.3. Physical and Chemical Properties

| Microbial Type | Microorganisms | Polysaccharides | Mw | Monosaccharide Composition | Physical Properties | Enhanced Bioactivities | Refences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Lactobacillus plantarum NCU116 | Momordica charantia L. polysaccharides | ↓ | Galactose ↑ (29.71–34.99%), Glucose ↓ (14.24–10.48%), Mannose ↓ (14.24–1.85%) | Viscosity ↓ | Antioxidant activity, anti-diabetic activity | [78] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum NCU137 | coix seed polysaccharides | ↓ | Glucose ↑ (68.61–72.91%) | Immunomodulatory activity | [24] | ||

| Lactobacillus plantarum M616 | Chinese yam polysaccharides | ↓ | Glccose ↑ 3.34%, Rhamnose ↓ 34.3%, Arabinose ↓ 48.4%, Galactose ↓ 15.0%, Mannose ↓ 15.6% | Anti-inflammatory activity | [53] | ||

| Bacillus sp. DU-106 | Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide | ↓ | Mannose ↑ (35.65–53.97%) | Immunomodulatory activity | [79] | ||

| Lactobacillus fermentum 21828 | Lentinus edodes polysaccharides | ↑ | Glucose ↑ (45.94–48.16%) | Immunomodulatory activity | [65] | ||

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Lanzhou Lily Bulbs polysaccharides | ↓ | Glucose ↑, Mannose ↓ | Particle size ↓, Solubility ↑ | Antioxidant activity | [74] | |

| Fungal | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | longan vinegar polysaccharides | ↓ | Glucose content ↓ Rhamnose ↑ | Viscosity ↓, Particle size ↓ | Immunomodulatory activity | [19] |

| Wine yeast | Lycium barbarum polysaccharide | ↓ | Anti-aging activity both in vivo and in vitro | [80] | |||

| Saccharomyces boulardii | Chinese yam polysaccharide | ↓ | Antioxidant | [45] | |||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae W5 | Blue honeysuckle polysaccharide | ↓ | Galactose ↑, Glccose ↑ | Solubility ↑ | Antioxidant and hypoglycemic in vitro | [69] | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae GIW-1 | Panax ginseng polysaccharide | ↓ | Arabinose ↑, Galactose ↓ | Antioxidant in vitro | [81] | ||

| Monascus purpureus | Ginseng polysaccharide | ↓ | Lower blood lipid | [82] |

5. The Role of Fermented Food–Polysaccharides in Improving Various Diseases by Regulating the Gut Microbiota

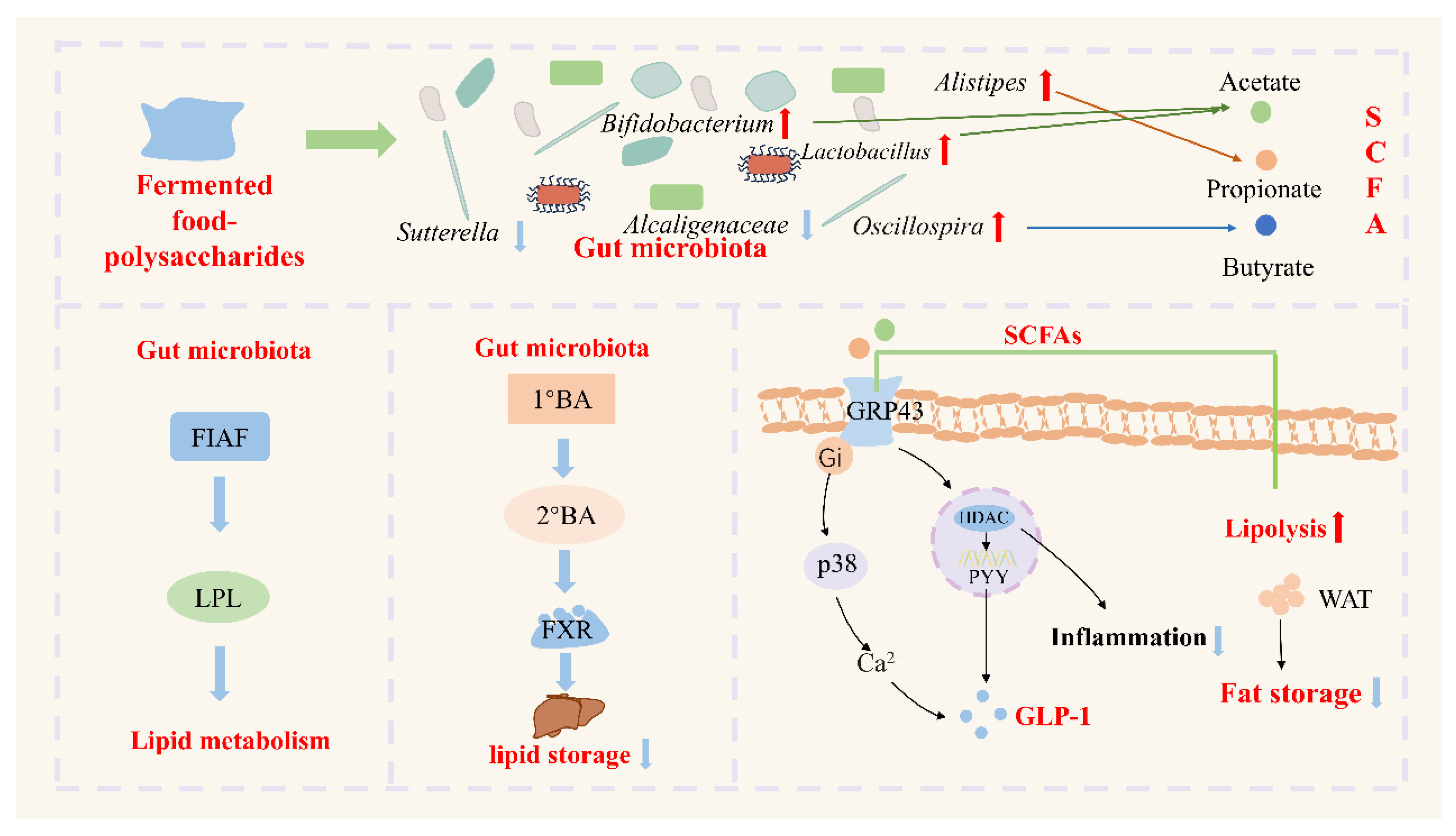

5.1. Metabolism-Related Diseases

5.2. Immune-Related Diseases

5.3. Intestinal-Related Diseases

5.4. Other Related Diseases

6. Safety Assessment and Insights of Fermented Food–Polysaccharides

7. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, L.; Chen, T.; Qi, X.; Li, H.; Xie, J.; Wang, L.; Xie, J.; Huang, Z. Exopolysaccharides from genistein-stimulated Monascus purpureus ameliorate cyclophosphamide-induced intestinal injury via PI3K/AKT-MAPKs/NF-κB pathways and regulation of gut microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 12986–13002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, M.F.; Artis, D.; Becker, C. The intestinal barrier: A pivotal role in health, inflammation, and cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 10, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Xie, L.; Shen, M.; Yu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J. Recent advances in Astragalus polysaccharides: Structural characterization, bioactivities and gut microbiota modulation effects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 153, 104707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Tang, Y.; Zha, M.; Xie, K.; Tan, J. The structure-function relationships and interaction between polysaccharides and intestinal microbiota: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 291, 139063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, H.; Liang, B.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Fang, S.; Xie, K.; Tan, J. The regulatory effect of polysaccharides on the gut microbiota and their effect on human health: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 132170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Shen, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, J. Structure, function and food applications of carboxymethylated polysaccharides: A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Sun, M.; Xu, L.; Kuang, H.; Xu, C.; Guo, L. The multiple benefits of bioactive polysaccharides: From the gut to overall health. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 152, 104677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Yan, M.; Liu, D.; Tao, C.; Hu, B.; Sun, S.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, L. Research progress on the structural characterization, biological activity and product application of polysaccharides from Crataegus pinnatifida. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 244, 125408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zou, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Zhai, S.; Chang, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J.; Luan, F.; Shi, Y. Extraction, purification, structural features, and pharmacological properties of polysaccharides from Houttuynia cordata: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Cui, F.J.; Sun, L.; Zan, X.Y.; Sun, W.J. Recent advances in Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides: Structures/bioactivities, biosynthesis and regulation. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, T.; Chen, X. A review of the antibacterial activity and mechanisms of plant polysaccharides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 123, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho Do, M.; Seo, Y.S.; Park, H.Y. Polysaccharides: Bowel health and gut microbiota. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1212–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, H.; Xiao, H.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, B.; Zeng, M. Recent advances in the anti-aging effects of natural polysaccharides: Sources, structural characterization, action mechanisms and structure-activity relationships. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 160, 105000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, R.O.; Castro, P.R.; Fachi, J.L.; Nirello, V.D.; El-Sahhar, S.; Imada, S.; Pereira, G.V.; Pral, L.P.; Araújo, N.V.P.; Fernandes, M.F.; et al. Inulin diet uncovers complex diet-microbiota-immune cell interactions remodeling the gut epithelium. Microbiome 2023, 11, 90. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos, W.M.; Tilg, H.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. Gut microbiome and health: Mechanistic insights. Gut 2022, 71, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Pei, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W.; Lu, W. Bridging dietary polysaccharides and gut microbiome: How to achieve precision modulation for gut health promotion. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 292, 128046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Song, Y.; Bi, X.; Liu, X.; Xing, Y.; Che, Z. Characterization of sea buckthorn polysaccharides and the analysis of its regulatory effect on the gut microbiota imbalance induced by cefixime in mice. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 104, 105511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xie, L.; Huang, Z.; Xie, J. Recent advances in polysaccharide biomodification by microbial fermentation: Production, properties, bioactivities, and mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 12999–13023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.G.; Zhu, W.L.; Yu, Y.S.; Zou, B.; Xu, Y.J.; Xiao, G.S.; Wu, J.J. The variation on structure and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharide during the longan pulp fermentation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-H.; Fan, S.-T.; Huang, D.-F.; Yu, Q.; Liu, X.-Z.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Xiong, T.; Nie, S.-P.; Xie, M.-Y. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum NCU116 fermentation on Asparagus officinalis polysaccharide: Characterization, antioxidative, and immunoregulatory activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 10703–10711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.J.; Zhang, X.; Dai, J.F.; Ma, Y.G.; Jiang, J.G. Effect of fermentation modification on the physicochemical characteristics and anti-aging related activities of Polygonatum kingianum polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 235, 123661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Tang, X.; Wang, L.; Gu, X.; Savelkoul, H.F.J.; Li, J. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction, Characterization, and Antioxidant Activities of the Polysaccharides from Fermented Astragalus membranaceus. Molecules 2025, 30, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Cheng, S.; Ding, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, M.; Man, C.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y. A comparison of study on intestinal barrier protection of polysaccharides from Hericium erinaceus before and after fermentation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Yin, H.; Zhong, Y.; Hu, J.; Xia, S.; Wang, Z.; Nie, S.; Xie, M. Polysaccharides from fermented coix seed modulates circulating nitrogen and immune function by altering gut microbiota. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1994–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.; Shen, F.; Zhu, H.; Mu, W.; Qian, H.; Liu, Y. Extracellular polysaccharides from Sporidiobolus pararoseus alleviates rheumatoid through ameliorating gut barrier function and gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 260, 129436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, F.; Jin, Z.; Xia, X. Ecological succession and functional characteristics of lactic acid bacteria in traditional fermented foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 5841–5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, R.; Gao, M.; Li, Z.; Feng, Y.; et al. Effect of Lactobacillus fermentation on the structural feature, physicochemical property, and bioactivity of plant and fungal polysaccharides: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 148, 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Hong, S.; Zhang, J.-R.; Liu, P.-H.; Li, S.; Wen, Z.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, G.; Habimana, O.; Shah, N.P.; et al. The effect of lactic acid bacteria fermentation on physicochemical properties of starch from fermented proso millet flour. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Zabidi, N.A.; Foo, H.L.; Loh, T.C.; Mohamad, R.; Abdul Rahim, R. Enhancement of versatile extracellular cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic enzyme productions by Lactobacillus plantarum RI 11 isolated from Malaysian food using renewable natural polymers. Molecules 2020, 25, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Su, D.; Lee, Y.-K.; Zou, X.; Dong, L.; Deng, M.; Zhang, R.; Huang, F.; Zhang, M. Accumulation of Water-Soluble Polysaccharides during Lychee Pulp Fermentation with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Involves Endoglucanase Expression. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 73, 3669–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, T.; Jiang, T.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Dong, B.; Wu, Q.; Gu, B. Carbohydrate-active enzyme profiles of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strain 84-3 contribute to flavor formation in fermented dairy and vegetable products. Food Chem. X 2023, 20, 101036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, P.; Petrov, K.; Petrova, P. The cell wall anchored β-fructosidases of Lactobacillus paracasei: Overproduction, purification, and gene expression control. Process Biochem. 2017, 52, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, M.; Zheng, J.; Gänzle, M.G. Bacillus species in food fermentations: An underappreciated group of organisms for safe use in food fermentations. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2023, 50, 101007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, Q.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Z.; Tang, J.; Xu, Y. Bacillus licheniformis affects the microbial community and metabolic profile in the spontaneous fermentation of Daqu starter for Chinese liquor making. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 250, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthilkumar, P.K.; Uma, C.; Saranraj, P. Amylase production by Bacillus sp. using cassava as substrate. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Arch. 2012, 3, 274–280. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, R.A.; Berrin, J.G.; McKee, L.S.; Bissaro, B. Fungal cell walls: The rising importance of carbohydrate-active enzymes. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 1085–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.; Ortega, N.; Martín-Santamaría, M.; Acedo, A.; Marquina, D.; Pascual, O.; Rozès, N.; Zamora, F.; Santos, A.; Belda, I. Occurrence and enological properties of two new non-conventional yeasts (Nakazawaea ishiwadae and Lodderomyces elongisporus) in wine fermentations. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 305, 108255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wu, Q.; Xu, Y.; Sun, B. Synergistic effect of multiple saccharifying enzymes on alcoholic fermentation for Chinese Baijiu production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00013–e00020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Miao, W.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, N.; Wu, J.L. Microbiota drive insoluble polysaccharides utilization via microbiome-metabolome interplay during Pu-erh tea fermentation. Food Chem. 2022, 377, 132007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilgendorf, K.; Wang, Y.; Miller, M.J.; Jin, Y.S. Precision fermentation for improving the quality, flavor, safety, and sustainability of foods. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2024, 86, 103084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, M.A.; Hartley, C.J.; Maloney, G.; Tyndall, S. Innovation in precision fermentation for food ingredients. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 6218–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, H.; Wu, M.; Li, Y.; Xia, W.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, W. Physicochemical properties, antioxidant and cardioprotective activities of polysaccharides from fermented Polygonatum kingianum with Lactobacillus species. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 216, 118699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Shi, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, J. Response surface methodology for the fermentation of polysaccharides from Auricularia auricula using Trichoderma viride and their antioxidant activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, M.; Li, R.; Qu, Q.; Li, Z.; Feng, M.; Tian, Y.; Ren, W.; et al. Exploring the prebiotic potential of fermented astragalus polysaccharides on gut microbiota regulation in vitro. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Kang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, C.; Hao, L.; Huang, J.; Lu, J.; Jia, S.; Yi, J. Antioxidant properties and digestion behaviors of polysaccharides from Chinese yam fermented by Saccharomyces boulardii. LWT 2022, 154, 112752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, A.; Feng, X.; Sheng, Y.; Song, Z. Optimization of the Artemisia polysaccharide fermentation process by Aspergillus niger. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 842766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghonemy, D.H. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of exopolysaccharides produced by a novel Aspergillus sp. DHE6 under optimized submerged fermentation conditions. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 36, 102150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zu, Y.; Li, X.; Meng, Q.; Long, X. Recent progress towards industrial rhamnolipids fermentation: Process optimization and foam control. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 298, 122394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, P. Active polysaccharides from Lentinula edodes and Pleurotus ostreatus by addition of corn straw and xylosma sawdust through solid-state fermentation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 228, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Armenta, R.E.; Brooks, M.S.L. Arachidonic acid production by Mortierella alpina MA2-2: Optimization of combined nitrogen sources in the culture medium using mixture design. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 29, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholzen, K.C.; Arnér, E.S. Cellular activity of the cytosolic selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1) is modulated by copper and zinc levels in the cell culture medium. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2025, 88, 127624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Xie, J.; Chen, X.; Tao, X.; Xie, J.; Shi, X.; Huang, Z. Comparative transcriptome analysis of Monascus purpureus at different fermentation times revealed candidate genes involved in exopolysaccharide biosynthesis. Food Res. Int. 2022, 160, 111700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Sun, G.; Zhao, R.; Zhou, W.-W.; Cheong, K.-L.; Wang, Z.; Feng, S.; et al. Effects of microbial fermentation on the anti-inflammatory activity of Chinese yam polysaccharides. Front. Nutr. 2025, 11, 1509624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Fang, Y.; Huang, W.; Lei, P.; Xu, X.; Sun, D.; Wu, L.; Xu, H.; Li, S. Effect of surfactants on the production and biofunction of Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide through submerged fermentation. LWT 2022, 163, 113602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lu, L.; Song, T.; Xu, X.; Yu, J.; Liu, T. Optimization of Cordyceps sinensis fermentation Marsdenia tenacissima process and the differences of metabolites before and after fermentation. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hereher, F.; ElFallal, A.; Abou-Dobara, M.; Toson, E.; Abdelaziz, M.M. Cultural optimization of a new exopolysaccharide producer “Micrococcus roseus”. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, H.; Sun, H.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Fu, J. Optimization of Fermentation Culture Medium for Sanghuangporus alpinus Using Response-Surface Methodology. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, H.; He, H.; Hua, F.; Wang, Z.J.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Q. Production of Polysaccharides from Angelica sinensis by Microbial Fermentation. BioResources 2024, 19, 5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolmeh, M.; Jafari, S.M. Applications of response surface methodology in the food industry processes. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, K.M.; Survase, S.A.; Saudagar, P.S.; Lele, S.S.; Singhal, R.S. Comparison of artificial neural network (ANN) and response surface methodology (RSM) in fermentation media optimization: Case study of fermentative production of scleroglucan. Biochem. Eng. J. 2008, 41, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breig, S.J.M.; Luti, K.J.K. Response surface methodology: A review on its applications and challenges in microbial cultures. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021, 42, 2277–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinestock, T.; Short, M.; Ward, K.; Guo, M. Computer-aided chemical engineering research advances in precision fermentation. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2024, 58, 101196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, L.; Shao, M.; Man, C.; Jiang, Y. Research on degradation of polysaccharides during Hericium erinaceus fermentation. LWT 2023, 173, 114276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.-J.; Hong, T.; Shi, H.-F.; Yin, J.-Y.; Koev, T.; Nie, S.-P.; Gilbert, R.G.; Xie, M.-Y. Probiotic fermentation modifies the structures of pectic polysaccharides from carrot pulp. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 251, 117116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Yue, Y.; Wang, X.; Han, M.; Yue, T.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Z. Structure and immunomodulatory activity of Lentinus edodes polysaccharides modified by probiotic fermentation. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, K.; Cheng, Y.; Sheng, Q.; Kurtovic, I.; Yuan, Y.; Yue, T. Tibetan kefir grains fermentation alters physicochemical properties and improves antioxidant activities of Lycium barbarum pulp polysaccharides. Food Chem. 2024, 453, 139659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Wei, H.; He, L.; Hu, C.; Cheng, S.; Ji, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Huang, X.; et al. Fermentation-mediated variations in structure and biological activity of polysaccharides from Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Diels et Gilg. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Yu, Y. Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum FM 17 fermentation on jackfruit polysaccharides: Physicochemical, structural, and bioactive properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 258, 128988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, F.; Cao, X.; Wang, X.; Ren, Y.; Ge, J. Structural characteristics and bioactivities of polysaccharides from blue honeysuckle after probiotic fermentation. LWT 2022, 165, 113764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, P.; Tan, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Bai, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, L.; Teng, D.; Tian, J.; et al. Effects of L. plantarum dy-1 fermentation time on the characteristic structure and antioxidant activity of barley β-glucan in vitro. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; You, S.; Wang, D.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, J.; An, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, C. Fermented Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides protect UVA—Induced photoaging of human skin fibroblasts. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 1275–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zou, S.; Cen, Q.; Hu, W.; Tan, F.; Chen, H.; Hui, F.; Da, Z.; Zeng, X. Effects of Ganoderma lucidum fermentation on the structure of Tartary buckwheat polysaccharide and its impact on gut microbiota composition. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 140944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fan, S.; Huang, D.; Xiong, T.; Nie, S.; Xie, M. Polysaccharides from fermented Asparagus officinalis with Lactobacillus plantarum NCU116 alleviated liver injury via modulation of glutathione homeostasis, bile acid metabolism, and SCFA production. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 7681–7695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Liu, X.; Zhao, B.; Abubaker, M.A.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J. Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum fermentation on the chemical structure and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from bulbs of Lanzhou lily. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 29839–29851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Gu, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Xiao, A.; Liu, G. Effects of Lactobacillus fermentation on Eucheuma spinosum polysaccharides: Characterization and mast cell membrane stabilizing activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 310, 120742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, S.-H.; Yang, F.; Sahu, S.K.; Luo, R.-Y.; Liao, S.-L.; Wang, H.-Y.; Jin, T.; Wang, L.; Zhang, P.-F.; Liu, X.; et al. Deciphering the composition and functional profile of the microbial communities in Chinese Moutai liquor starters. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Zhang, S.; Waterhouse, G.I.; Zhou, T.; Du, Y.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Wu, P. Yeast fermentation of apple and grape pomaces affects subsequent aqueous pectin extraction: Composition, structure, functional and antioxidant properties of pectins. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 133, 107945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.-J.; Li, M.-Z.; Gao, H.; Hu, J.-L.; Nie, Q.-X.; Chen, H.-H.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Xie, M.-Y.; Nie, S.-P. Polysaccharides from fermented Momordica charantia L. with Lactobacillus plantarum NCU116 ameliorate metabolic disorders and gut microbiota change in obese rats. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 2617–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Dai, L.; Lu, S.; Luo, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Li, J.; Li, P.; Du, B. Effect of Bacillus sp. DU-106 fermentation on Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide: Structure and immunoregulatory activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 135, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, Q.; Fang, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, D.; Li, M. The anti-aging activity of Lycium barbarum polysaccharide extracted by yeast fermentation: In vivo and in vitro studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 209, 2032–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, Z.; You, Y.; Li, W.; Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. Enhanced uronic acid content, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities of polysaccharides from ginseng fermented by Saccharomyces cerevisiae GIW-1. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, M.; Qu, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Feng, M.; Tian, Y.; Ren, W.; Shi, X. Fermentation interactions and lipid-lowering potential of Monascus purpureus fermented Ginseng. Food Biosci. 2025, 66, 106260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Chang, S.; Zhang, X.; Luo, F.; Li, W.; Ren, J. The fate of dietary polysaccharides in the digestive tract. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 150, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Déjean, G.; Tamura, K.; Cabrera, A.; Jain, N.; Pudlo, N.A.; Pereira, G.; Viborg, A.H.; Van Petegem, F.; Martens, E.C.; Brumer, H. Synergy between cell surface glycosidases and glycan-binding proteins dictates the utilization of specific beta (1, 3)-glucans by human gut Bacteroides. MBio 2020, 11, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, H.; Xiong, L.; Jin, X.; Zhu, T.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H. Structural characterization and prebiotic activity of Bletilla striata polysaccharide prepared by one-step fermentation with Bacillus licheniformis BJ2022. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 258, 128822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, K.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, R.; Guan, H.; Tian, J. Targeting ion homeostasis in metabolic diseases: Molecular mechanisms and targeted therapies. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 212, 107579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.T.; Fu, Y.; Guo, H.; Yuan, Q.; Nie, X.R.; Wang, S.P.; Gan, R.Y. In vitro simulated digestion and fecal fermentation of polysaccharides from loquat leaves: Dynamic changes in physicochemical properties and impacts on human gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 168, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Yi, Y.; Shan, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Lü, X. Roles of intestinal Parabacteroides in human health and diseases. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2022, 369, fnac072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, E.; Ryan, P.M.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G.; Ross, R.P.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Stanton, C. Gut microbiota, obesity and diabetes. Postgrad. Med. J. 2016, 92, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Hu, J.; Nie, Q.; Nie, S. Effects of polysaccharides on glycometabolism based on gut microbiota alteration. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 92, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Yang, F.-Q.; Tang, P.; Gao, T.-H.; Yang, C.-X.; Tan, L.; Yue, P.; Hua, Y.-N.; Liu, S.-J.; Guo, J.-L. Regulation of the intestinal flora: A potential mechanism of natural medicines in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Hong, J.; Li, H.; Hu, Y.; Jia, L.; Cai, D.; Zhao, R. Butyrate stimulates adipose lipolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation through histone hyperacetylation-associated β3—Adrenergic receptor activation in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Exp. Physiol. 2017, 102, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmody, R.N.; Bisanz, J.E. Roles of the gut microbiome in weight management. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.W.; Huang, Z.Q.; Liu, K.; Li, D.Z.; Mo, T.L.; Liu, Q. The role of intestinal microbiota and metabolites in intestinal inflammation. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 288, 127838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, C.; Fan, X.; Xie, Y.; Zou, Y.; Geng, Z.; Huang, C. Effects of solid fermentation on Polygonatum cyrtonema polysaccharides: Isolation, characterization and bioactivities. Molecules 2023, 28, 5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.H.; Kang, S.G.; Park, J.H.; Yanagisawa, M.; Kim, C.H. Short-chain fatty acids activate GPR41 and GPR43 on intestinal epithelial cells to promote inflammatory responses in mice. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, E.C.; Piper, C.J.; Matei, D.E.; Blair, P.A.; Rendeiro, A.F.; Orford, M.; Alber, D.G.; Krausgruber, T.; Catalan, D.; Klein, N.; et al. Microbiota-derived metabolites suppress arthritis by amplifying aryl-hydrocarbon receptor activation in regulatory B cells. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhu, S.; Yang, H.; Wang, Z. Polygonatum odoratum fermented polysaccharides enhance the immunity of mice by increasing their antioxidant ability and improving the intestinal flora. Food Biosci. 2024, 58, 103650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Chen, T.; Li, H.; Xiao, J.; Wang, L.; Kim, S.-K.; Huang, Z.; Xie, J. An exopolysaccharide from genistein-stimulated monascus purpureus: Structural characterization and protective effects against DSS-induced intestinal barrier injury associated with the gut microbiota-modulated short-chain fatty acid-TLR4/MAPK/NF-κB cascade response. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 7476–7496. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, J.K.; Davenport, E.R.; Beaumont, M.; Jackson, M.A.; Knight, R.; Ober, C.; Spector, T.D.; Bell, J.T.; Clark, A.G.; Ley, R.E. Genetic determinants of the gut microbiome in UK twins. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Swallah, M.S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J.; Lu, J.; Yu, H. Structural characteristics of insoluble dietary fiber from okara with different particle sizes and their prebiotic effects in rats fed high-fat diet. Foods 2022, 11, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Deng, Z.; Lu, L.; Ouyang, Y.; Zhong, S.; Luo, T.; Fan, Y.; Zheng, L. Polysaccharides from soybean residue fermented by Neurospora crassa alleviate DSS-induced gut barrier damage and microbiota disturbance in mice. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 5739–5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Sun, C.; Yuan, J.; Tsopmejio, I.S.N.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Song, H. Hericium caput-medusae (Bull.: Fr.) Pers. fermentation concentrate polysaccharides improves intestinal bacteria by activating chloride channels and mucus secretion. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 300, 115721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, J.; Ison, J.; Tyagi, S.C.; Tyagi, N. The role of gut microbiota in bone homeostasis. Bone 2020, 135, 115317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Cheng, J.; Liu, L.; Luo, J.; Peng, X. Lactobacillus acidophilus (LA) fermenting Astragalus polysaccharides (APS) improves calcium absorption and osteoporosis by altering gut microbiota. Foods 2023, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-Y.; Zhou, Y.-C.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.-Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.-F.; Liu, W.-H.; Liu, G.-M.; Liu, Q.-M. Fermented Gracilaria lemaneiformis polysaccharides alleviate food allergy by regulating Treg cells and gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 269, 132215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Liu, F.; Zuo, P.; Huang, G.; Song, Z.; Wang, T.; Lu, H.; Guo, F.; Han, C.; Sun, G. Practical application of antidiabetic efficacy of Lycium barbarum polysaccharide in patients with type 2 diabetes. Med. Chem. 2015, 11, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.-C.; Chen, S.-C.; Wang, C.-H.; Hung, C.-M.; Peng, M.-T.; Liu, C.-T.; Chang, Y.-S.; Kuo, W.-L.; Chou, H.-H.; Yeh, K.-Y.; et al. Astragalus polysaccharides improve adjuvant chemotherapy-induced fatigue for patients with early breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wei, Y.; Li, F.; Weng, X.; Wei, X. Regulation of fungal community and the quality formation and safety control of Pu-erh tea. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 4546–4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, K.F.; Ng, K.R.; Samarasiri, M.; Chen, W.N. Precision fermentation to advance fungal food fermentations. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 47, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licandro, H.; Ho, P.H.; Nguyen, T.K.C.; Petchkongkaew, A.; Van Nguyen, H.; Chu-Ky, S.; Nguyen, T.V.A.; Lorn, D.; Waché, Y. How fermentation by lactic acid bacteria can address safety issues in legumes food products? Food Control. 2020, 110, 106957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Ding, Y.; Li, S.; Sang, X.; Li, T.; Zhao, Q.; Yu, S. Structure, in vitro digestive characteristics and effect on gut microbiota of sea cucumber polysaccharide fermented by Bacillus subtilis Natto. Food Res. Int. 2023, 169, 112872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lai, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Ding, L.; Wang, J.; Li, N.; Wang, Z.; et al. Structural characterization and combined immunomodulatory activity of fermented Chinese yam polysaccharides with probiotics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 142290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hu, K.; Chen, Y.; Lai, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Zhao, N.; Liu, S. Effect of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum fermentation on the physicochemical, antioxidant activity and immunomodulatory ability of polysaccharides from Lvjian okra. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 257, 128649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, C.; Li, M.; Peng, K.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wang, H.; Yi, Y. Physicochemical and bioactive modifications of lotus root polysaccharides associated with probiotic fermentation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 136211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.-I.; La, I.-J.; Han, X.; Men, X.; Lee, S.-J.; Oh, G.; Kwon, H.-Y.; Kim, Y.-D.; Seong, G.-S.; Kim, S.-H.; et al. Immunomodulatory effect of polysaccharide from fermented Morinda citrifolia L. (Noni) on RAW 264.7 macrophage and Balb/c mice. Foods 2022, 11, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, O.; Sudakaran, S.; Blonquist, T.; Mah, E.; Durkee, S.; Bellamine, A. Effect of arabinogalactan on the gut microbiome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial in healthy adults. Nutrition 2021, 90, 111273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Z.C.; Villa, M.M.; Durand, H.K.; Jiang, S.; Dallow, E.P.; Petrone, B.L.; Silverman, J.D.; Lin, P.-H.; David, L.A. Microbiota responses to different prebiotics are conserved within individuals and associated with habitual fiber intake. Microbiome 2022, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polysaccharides | Microorganisms | Optimization Method | Optimal Condition | Evaluation Indicators | Refences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polygonatum kingianum polysaccharides | Lactobacillus plantarum (M2) | RSM | 6.6% golden pine addition, 4.7% Inoculation rate, Temperature: 36 °C | Viable bacteria count: 8.9 × 108 CFU/mL | [42] |

| Auricularia auricula polysaccharides | Trichoderma viride | RSM | Moisture content: 61.7%, inoculation amount: 12.4%, temperature: 31.0 °C, time: 5.5 days | Degradation rate: 26.89 ± 0.14% | [43] |

| Astragalus polysaccharides (APS) | Lactobacillus rhamnosus | RSM | APS: 10.28%, inoculate 5.83%, time: 35.6 h, temperature: 34.6 °C | Viable bacteria count: 1.348 × 109 CFU/mL | [44] |

| Chinese yam polysaccharides | Saccharomyces boulardii | Single-factor optimization method | Time: 36 h, inoculation volume: 6%, material-to-liquid ratio: 1:25 g/mL | The total reduction function (TRP) is the strongest | [45] |

| Artemisia polysaccharide | Aspergillus niger | RSM | Inoculation amount: 5%, temperature: 36 °C, time: 2 days, shaker speed: 180 r/min | Yield: 17.04% | [46] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, A.; Zhang, N.; Dong, H.; Huang, Y.; Xie, L. Fermented Food–Polysaccharides as Gut Health Regulators: Sources, Optimization, Structural Characteristics and Mechanism. Foods 2025, 14, 4108. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234108

Zhou A, Zhang N, Dong H, Huang Y, Xie L. Fermented Food–Polysaccharides as Gut Health Regulators: Sources, Optimization, Structural Characteristics and Mechanism. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4108. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234108

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Aoxiang, Nanhai Zhang, Huanhuan Dong, Yousheng Huang, and Liuming Xie. 2025. "Fermented Food–Polysaccharides as Gut Health Regulators: Sources, Optimization, Structural Characteristics and Mechanism" Foods 14, no. 23: 4108. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234108

APA StyleZhou, A., Zhang, N., Dong, H., Huang, Y., & Xie, L. (2025). Fermented Food–Polysaccharides as Gut Health Regulators: Sources, Optimization, Structural Characteristics and Mechanism. Foods, 14(23), 4108. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234108