Deciphering the Complexity of Smoke Point in Virgin Olive Oils to Develop Simple Predictive Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Analytical Methods

2.2.1. Trade Quality Indices

2.2.2. Moisture and Volatile Matter

2.2.3. Oxidative Stability

2.2.4. Fatty Acid Composition

2.2.5. Lipophilic and Polar Phenolic Compounds

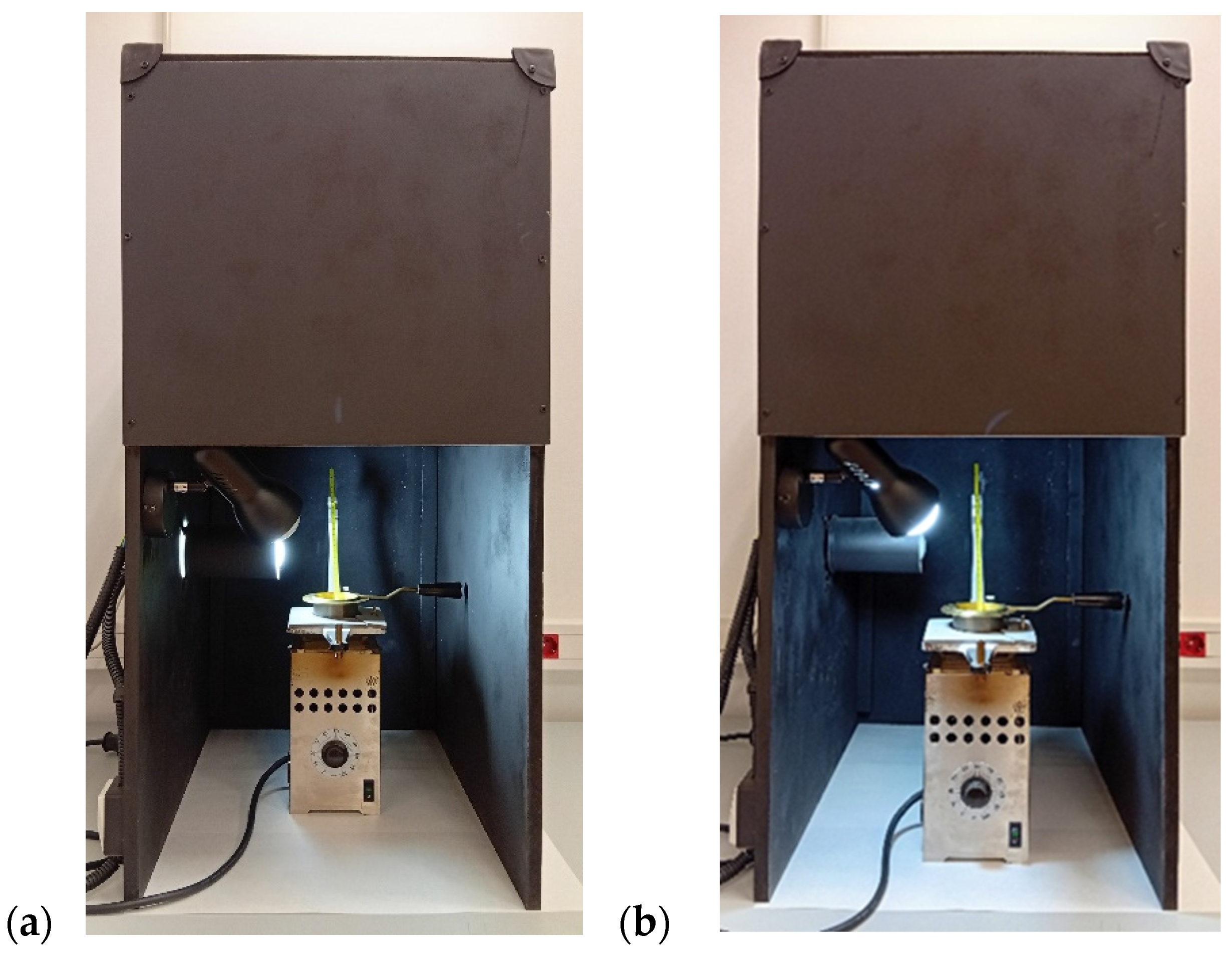

2.2.6. Smoke Point

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Models Using Partial Least Squares Regression

3.1.1. Model Building and Variable Selection

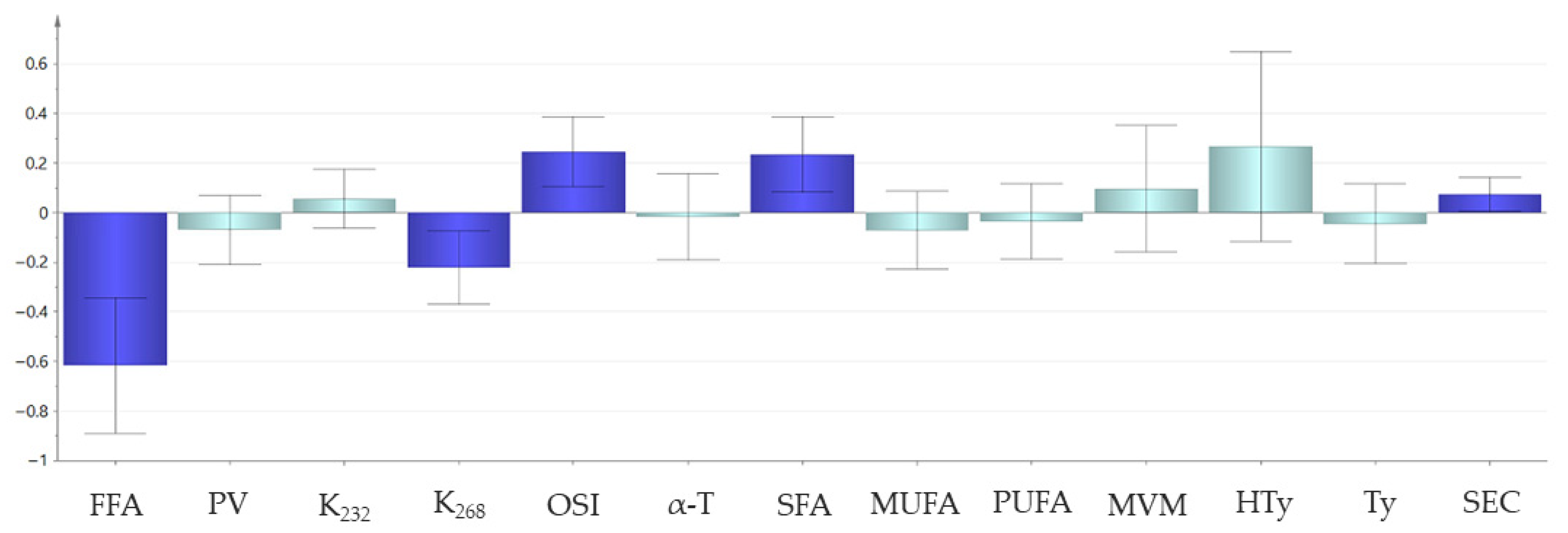

3.1.2. Relationship Between the Smoke Point and Other Quality and Compositional Parameters of Virgin Olive Oils

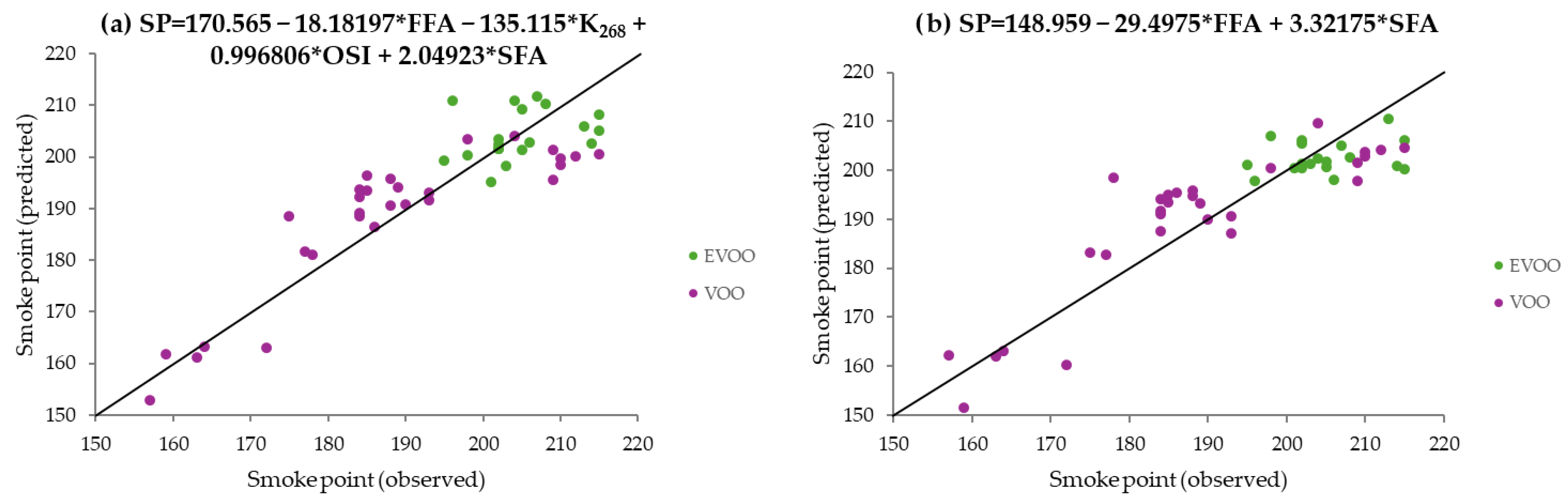

3.1.3. Predictive Models Using PLS

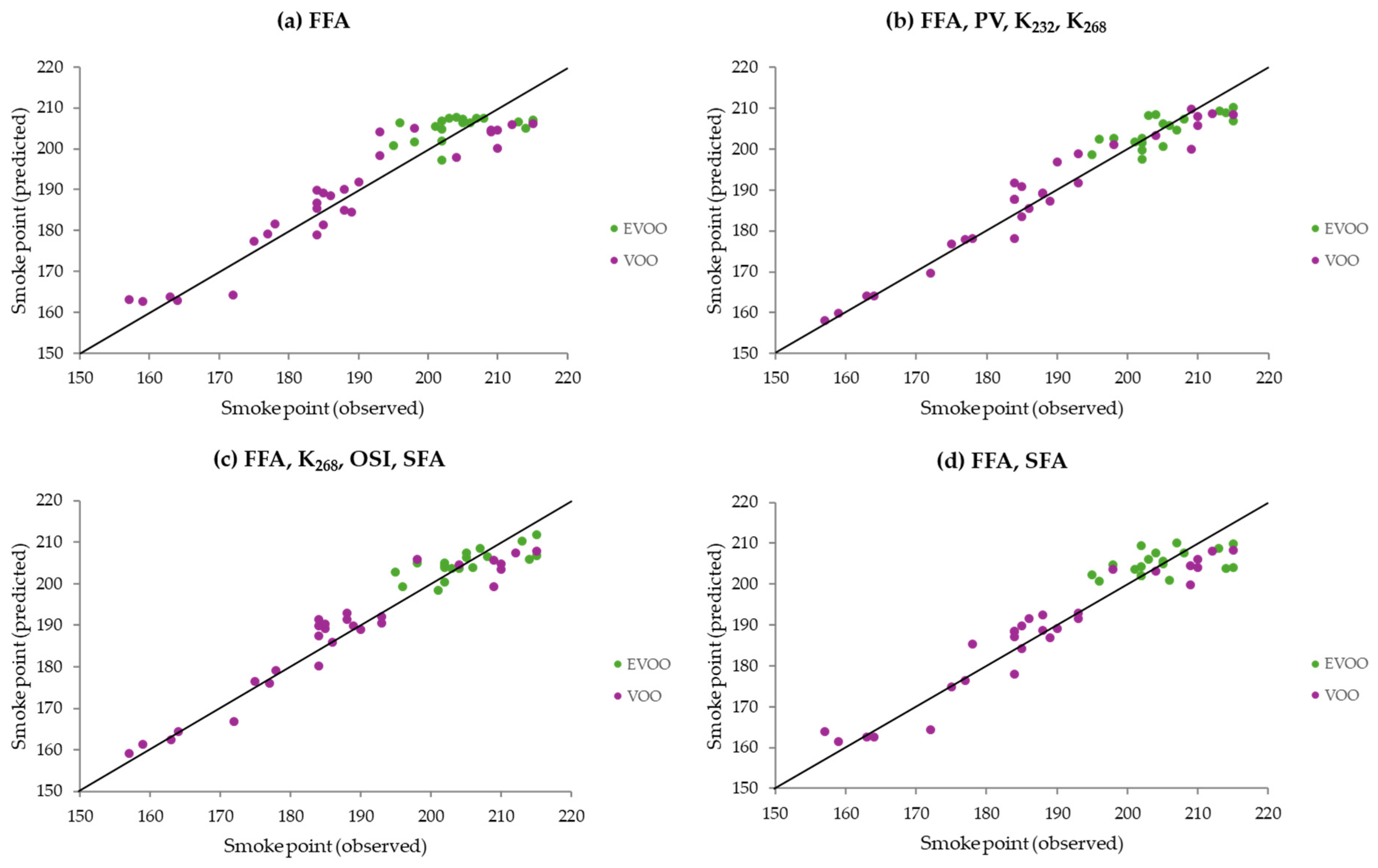

3.2. Models Using Gaussian Process Regression

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AOCS. Smoke, Flash and Fire Points Cleveland Open Cup Method; Official Method Cc 9a-48. In Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 7th ed.; AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tsaknis, J.; Spiliotis, V.; Lalas, S.; Gergis, V.; Dourtoglou, V. Quality Changes of Moringa Oleifera, Variety Mbololo of Kenya, Seed Oil during Frying. Grasas Aceites 1999, 50, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dobarganes, C.; Márquez-Ruiz, G. Analysis of Used Frying Oils. Lipid Technol. 2013, 25, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katragadda, H.R.; Fullana, A.; Sidhu, S.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Emissions of Volatile Aldehydes from Heated Cooking Oils. Food Chem. 2010, 120, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, K.L.; Delgado-Saborit, J.M.; Harrison, R.M. Emissions and Indoor Concentrations of Particulate Matter and Its Specific Chemical Components from Cooking: A Review. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 71, 260–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Sukalingam, K.; Xu, B. Impact of Consumption of Repeatedly Heated Cooking Oils on the Incidence of Various Cancers: A Critical Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 488–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Liu, W.; Meng, C.; Dong, J.; Zhang, S. Temperature-dependent particle mass emission rate during heating of edible oils and their regression models. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 323, 121221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ölzigen, S. Cooking as a Chemical Reaction: Culinary Science with Experiments, 2nd ed.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; ISBN 9788578110796. [Google Scholar]

- Culinary Institute of America (Ed.) The Professional Chef, 7th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 0471382574. [Google Scholar]

- Rossell, J.B. Factors Affecting the Quality of Frying Oils and Fats. In Frying: Improving Quality; Rossell, J.B., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2001; pp. 115–164. [Google Scholar]

- Dobarganes, M.C.; Velasco, J.; Márquez-Ruiz, G. La Calidad de Los Aceites y Grasas de Fritura. Aliment. Nutr. Salud 2002, 9, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, E.; Min, D.B. Chemistry of Deep-Fat Frying Oils. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österreichisches Lebensmittelbuch IV. Auflage Codexkapitel/B 30/Speisefette, Speiseöle, Streichfette Und Andere Fetterzeugnisse; Bundesministerium Arbeit, Soziales, Gesundheit Und Konsumentenschutz: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Matthäus, B. Utilization of High-Oleic Rapeseed Oil for Deep-Fat Frying of French Fries Compared to Other Commonly Used Edible Oils. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2006, 108, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.Y.; Sharifudin, M.S.; Hasmadi, M.; Chew, H.M. Frying Stability of Rice Bran Oil and Palm Olein. Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 20, 403–407. [Google Scholar]

- Quaglia, G.B.; Bucarelli, F.M. Effective Process Control in Frying. In Frying: Improving Quality; Rossell, J.B., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2001; pp. 236–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kalogianni, E.P.; Georgiou, D.; Romaidi, M.; Exarhopoulos, S.; Petridis, D.; Karastogiannidou, C.; Dimitreli, G.; Karakosta, P. Rapid Methods for Frying Oil Quality Determination: Evaluation with Respect to Legislation Criteria. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2017, 94, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallikarjunan, P.K.; Ngadi, M.O.; Chinnan, M.S. Breaded Fried Foods; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bockisch, M. (Ed.) Fats and Oils Handbook; AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-9818936-0-0. [Google Scholar]

- De Alzaa, F.; Guillaume, C.; Ravetti, L. Evaluation of Chemical and Physical Changes in Different Commercial Oils during Heating. Acta Sci. Nutr. Health 2018, 2, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Matthäus, B.; Brühl, L. Quality Parameters for the Evaluation of Cold-Pressed Edible Argan Oil. J. Für Verbraucherschutz Und Leb. 2014, 10, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunstone, F.D. (Ed.) Vegetable Oils in Food Technology: Composition, Properties and Uses, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4443-3268-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, G.-C.; Shao, C.-H.; Chen, C.-J.; Duh, P.-D. Effects of Antioxidant and Cholesterol on Smoke Point of Oils. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1997, 30, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.T.; Fang, B.; Wu, H.Y.; Shen, Y.M. Establishment of Mathematical Relationships between Smoke Point and Minor Compounds in Vegetable Oils Using Principal Component Regression Analysis. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2016, 51, 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dabbas, M.M.; Al-Jaloudi, R.; Abdullah, M.A.; Abughoush, M. Characterization of olive oil volatile compounds after elution through selected bleaching materials—Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis. Molecules 2023, 28, 6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU). 2022/2105 of 29 July 2022 Laying down Rules on Conformity Checks of Marketing Standards for Olive Oil and Methods of Analysis of the Characteristics of Olive Oil. Off. J. Eur. Union 2022, L 284, 23–48, its subsequent amendments. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Bremer, G.C.; Connell, K.N.; Ngai, C.; Anh, Q.; Pham, T.; Wang, S.; Flynn, M.; Ravetti, L.; Guillaume, C.; et al. Changes in Chemical Compositions of Olive Oil under Different Heating Temperatures Similar to Home Cooking. J. Food Chem. Nutr. 2016, 4, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, H.Y.; Roy, P.K.; Chattopadhyay, S. Thermal Degradation in Edible Oils by Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Calibrated with Iodine Values. Vib. Spectrosc. 2020, 106, 103018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öğütcü, M.; Aydeniz, B.; Büyükcan, M.B.; Yılmaz, E. Determining Frying Oil Degradation by Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Using Chemometric Techniques. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2012, 89, 1823–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOCS. Moisture and Volatile Matter, Vacuum Oven Method; Official Method Ca 2d-25. In Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 7th ed.; AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- AOCS. Oil Stability Index (OSI); Official Method Cd 12b-92. In Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 7th ed.; AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Varona, E.; Tres, A.; Rafecas, M.; Vichi, S.; Barroeta, A.C.; Guardiola, F. Methods to Determine the Quality of Acid Oils and Fatty Acid Distillates Used in Animal Feeding. MethodsX 2021, 8, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOCS. Determination of Tocopherols and Tocotrienols in Vegetable Oils and Fats by HPLC; Official Method Ce 8-89. In Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 7th ed.; AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vichi, S.; Cortés-Francisco, N.; Caixach, J. Insight into Virgin Olive Oil Secoiridoids Characterization by High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry and Accurate Mass Measurements. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1301, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOC. Determination of Biophenols in Olive Oils by HPLC; COI/T.20/Doc No 29; Review International Olive Oil Council: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nenadis, N.; Mastralexi, A.; Tsimidou, M.Z.; Vichi, S.; Quintanilla-Casas, B.; Donarski, J.; Bailey-Horne, V.; Butinar, B.; Miklavčič, M.; García González, D.L.; et al. Toward a Harmonized and Standardized Protocol for the Determination of Total Hydroxytyrosol and Tyrosol Content in Virgin Olive Oil (VOO). Extraction Solvent. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2018, 120, 1800099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, R.; Espartero, J.L.; Trujillo, M.; Ríos, J.J.; León-Camacho, M.; Alcudia, F.; Cert, A. Determination of Phenols, Flavones, and Lignans in Virgin Olive Oils by Solid-Phase Extraction and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Ultraviolet Detection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 2185–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ST123 Oil Smoke Tester-Edible Oil Tester Oil Smoke Point Analyzer for Animal and Vegetable Oils. Available online: https://gonoava.en.made-in-china.com/product/utqYnPBHsiVz/China-Edible-Oil-Tester-Oil-Smoke-Point-Analyzer-for-Animal-and-Vegetable-Oils.html?pv_id=1j1r14a56bd4&faw_id=1j1r14bdd4ec&bv_id=1j1r14dnsd19 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- GB/T 20795-2006; Determination of Smoking Point for Vegetable Fats and Oils. The Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- Rasmussen, C.E.; Williams, C.K.I. Gaussian Processes for Machine; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 026218253X. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio, R.; Harwood, J. (Eds.) Handbook of Olive Oil: Analysis and Properties, 2nd ed.; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4614-7776-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalua, C.M.; Allen, M.S.; Bedgood, D.R.; Bishop, A.G.; Prenzler, P.D.; Robards, K. Olive oil volatile compounds, flavour development and quality: A critical review. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, M.E.; Mannu, A.; Mele, A. NMR Determination of Free Fatty Acids in Vegetable Oils. Processes 2020, 8, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelló, J.-R.; Motilva, M.-J.; Tovar, M.-J.; Romero, M.-P. Changes in commercial virgin olive oil (cv Arbequina) during storage, with special emphasis on the phenolic fraction. Food Chem. 2004, 85, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Hahm, T.S.; Min, D.B. Hydroperoxide as a prooxidant in the oxidative stability of soybean oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2007, 84, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, R.; Domínguez, M.M.; Espartero, J.L.; Cert, A. Antioxidant Effect of Phenolic Compounds, α-Tocopherol, and Other Minor Components in Virgin Olive Oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7170–7175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.W.; Mier, W.; Giacosa, A.; Hull, W.E.; Spiegelhalder, B.; Bartsch, H. Phenolic Compounds and Squalene in Olive Oils: The Concentration and Antioxidant Potential of Total Phenols, Simple Phenols, Secoiridoids, Lignans and Squalene. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2000, 38, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díez-Betriu, A.; Romero, A.; Ninot, A.; Tres, A.; Vichi, S.; Guardiola, F. Subzero Temperature Storage to Preserve the Quality Attributes of Veiled Virgin Olive Oil. Foods 2023, 12, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klisović, D.; Novoselić, A.; Lukić, M.; Kraljić, K.; Brkić Bubola, K. Thermal-Induced Alterations in Phenolic and Volatile Profiles of Monovarietal Extra Virgin Olive Oils. Foods 2024, 13, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| M2 | M2 * | M2 ** | M2 *** | M3 * | M3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoeffCS | SEcv | CoeffCS | SEcv | CoeffCS | SEcv | CoeffCS | SEcv | CoeffCS | SEcv | CoeffCS | SEcv | |

| FFA | −0.498 1 | 0.115 | −0.66 | 0.184 | −0.674 | 0.192 | −0.736 | 0.15 | −0.751 | 0.109 | −0.807 | 0.161 |

| K268 | −0.26 | 0.157 | −0.108 | 0.262 | −0.133 | 0.263 | ||||||

| OSI | 0.341 | 0.084 | 0.231 | 0.264 | 0.216 | 0.13 | 0.163 | 0.147 | ||||

| SFA | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.309 | 0.256 | 0.315 | 0.251 | 0.291 | 0.145 | ||||

| Model | Variables | Latent Variables | R2X (%) | R2Y (%) | Q2 (%) | RMSEcv (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 13 | 3 | 65.1 | 85.9 | 78.6 | 7.09 |

| M2 | 4 | 1 | 42.7 | 78.3 | 76.9 | 7.38 |

| M2 * | 3 | 2 | 70.6 | 73.5 | 70.3 | 8.34 |

| M2 ** | 3 | 2 | 74.3 | 78.5 | 74.8 | 7.72 |

| M2 *** | 3 | 2 | 73.8 | 77.2 | 72.8 | 7.92 |

| M3 * | 2 | 2 | 100 | 72.5 | 71.6 | 8.18 |

| M3 | 2 | 1 | 52.2 | 76.7 | 75 | 7.68 |

| Model | Variables | MAE (°C) | MRE (%) | Max AE (°C) | Max RE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1SE | FFA | 4.69 | 2.40 | 10.82 | 5.61 |

| G2SE | FFA, PV | 4.69 | 2.40 | 10.82 | 5.61 |

| G3SE | FFA, PV, K232, K268 | 3.40 | 1.72 | 9.41 | 4.80 |

| G4SE | FFA, K268, OSI, SFA | 3.57 | 1.82 | 9.71 | 4.51 |

| G5SE | FFA, SFA | 3.87 | 1.99 | 9.62 | 4.82 |

| G1M3/2 | FFA | 4.50 | 2.29 | 11.20 | 5.80 |

| G2M3/2 | FFA, PV | 3.65 | 1.84 | 10.50 | 4.90 |

| G3M3/2 | FFA, PV, K232, K268 | 3.09 | 1.56 | 9.08 | 4.34 |

| G4M3/2 | FFA, K268, OSI, SFA | 3.42 | 1.74 | 9.77 | 4.68 |

| G5M3/2 | FFA, SFA | 3.84 | 1.96 | 10.96 | 5.10 |

| M2 | FFA, K268, OSI, SFA | 5.74 | 2.93 | 14.96 | 7.69 |

| M3 | FFA, SFA | 6.17 | 3.19 | 20.55 | 11.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Díez-Betriu, A.; Quintanilla-Casas, B.; Masdemont, J.J.; Tres, A.; Vichi, S.; Guardiola, F. Deciphering the Complexity of Smoke Point in Virgin Olive Oils to Develop Simple Predictive Models. Foods 2025, 14, 4099. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234099

Díez-Betriu A, Quintanilla-Casas B, Masdemont JJ, Tres A, Vichi S, Guardiola F. Deciphering the Complexity of Smoke Point in Virgin Olive Oils to Develop Simple Predictive Models. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4099. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234099

Chicago/Turabian StyleDíez-Betriu, Anna, Beatriz Quintanilla-Casas, Josep J. Masdemont, Alba Tres, Stefania Vichi, and Francesc Guardiola. 2025. "Deciphering the Complexity of Smoke Point in Virgin Olive Oils to Develop Simple Predictive Models" Foods 14, no. 23: 4099. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234099

APA StyleDíez-Betriu, A., Quintanilla-Casas, B., Masdemont, J. J., Tres, A., Vichi, S., & Guardiola, F. (2025). Deciphering the Complexity of Smoke Point in Virgin Olive Oils to Develop Simple Predictive Models. Foods, 14(23), 4099. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234099