Preharvest UVA-LED Enhancing Growth and Antioxidant Properties of Chinese Cabbage Microgreens: A Comparative Study of Single Versus Fractionated Irradiation Patterns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Microgreen Cultivation and Treatments

2.1.1. Growth Condition

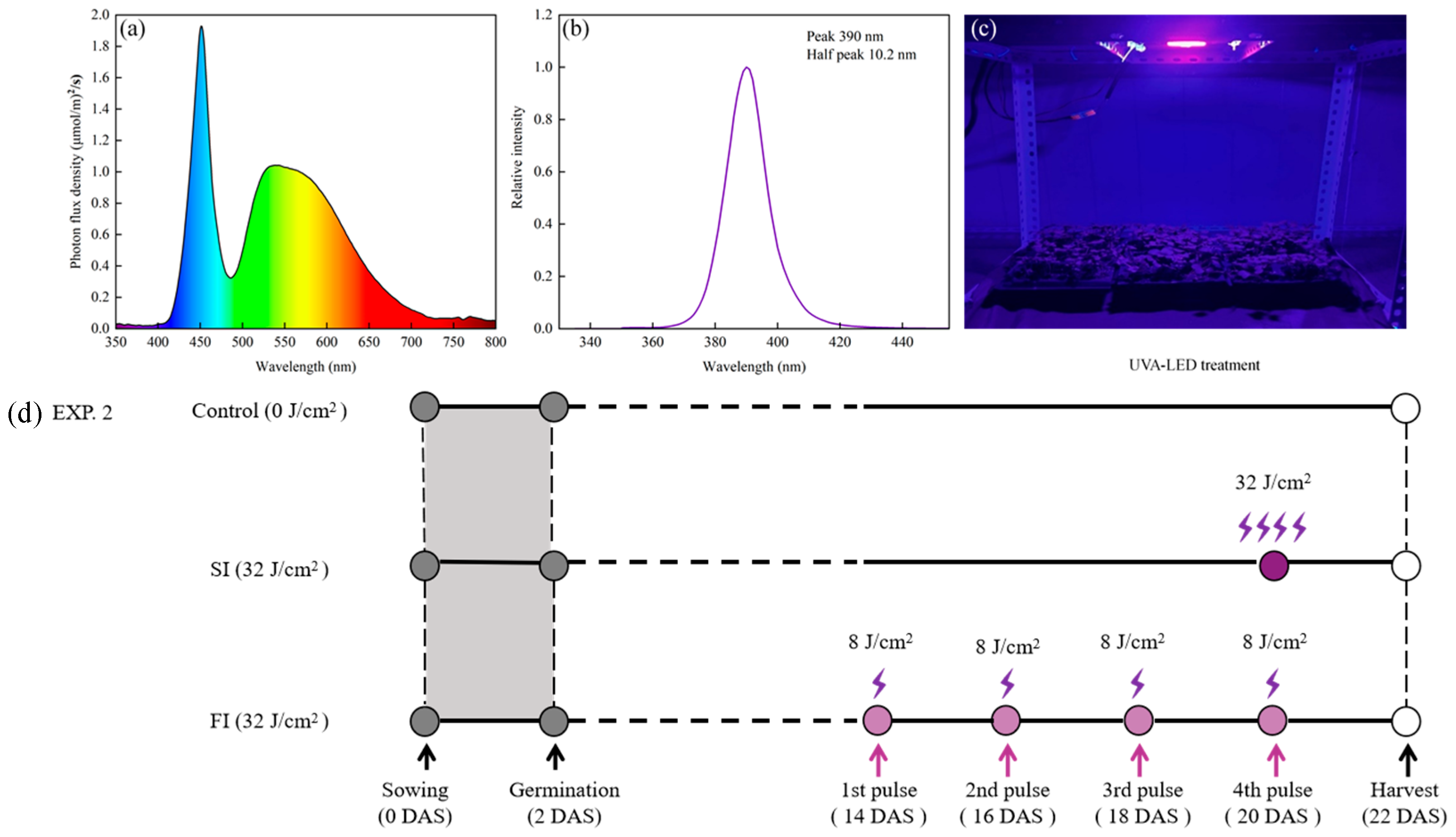

2.1.2. UVA-LED Irradiation Dose Selection

2.1.3. UVA-LED Irradiation Patterns Comparison

2.2. Growth Parameters Assay

2.2.1. Growth Morphology and Agronomy Traits

2.2.2. Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Assay

2.3. Antioxidants and Total Antioxidant Capacity Assay

2.3.1. Total Phenolic Compounds and Total Flavonoid Content Assay

2.3.2. Total Ascorbic Acid and Ascorbic Acid

2.3.3. Total Antioxidant Capacity Assay

2.4. Antioxidant Enzyme Activities and MDA Content Assay

2.4.1. Antioxidant Enzyme Activities Assays

2.4.2. MDA Content Assay

2.5. Nitrate Content Assay

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

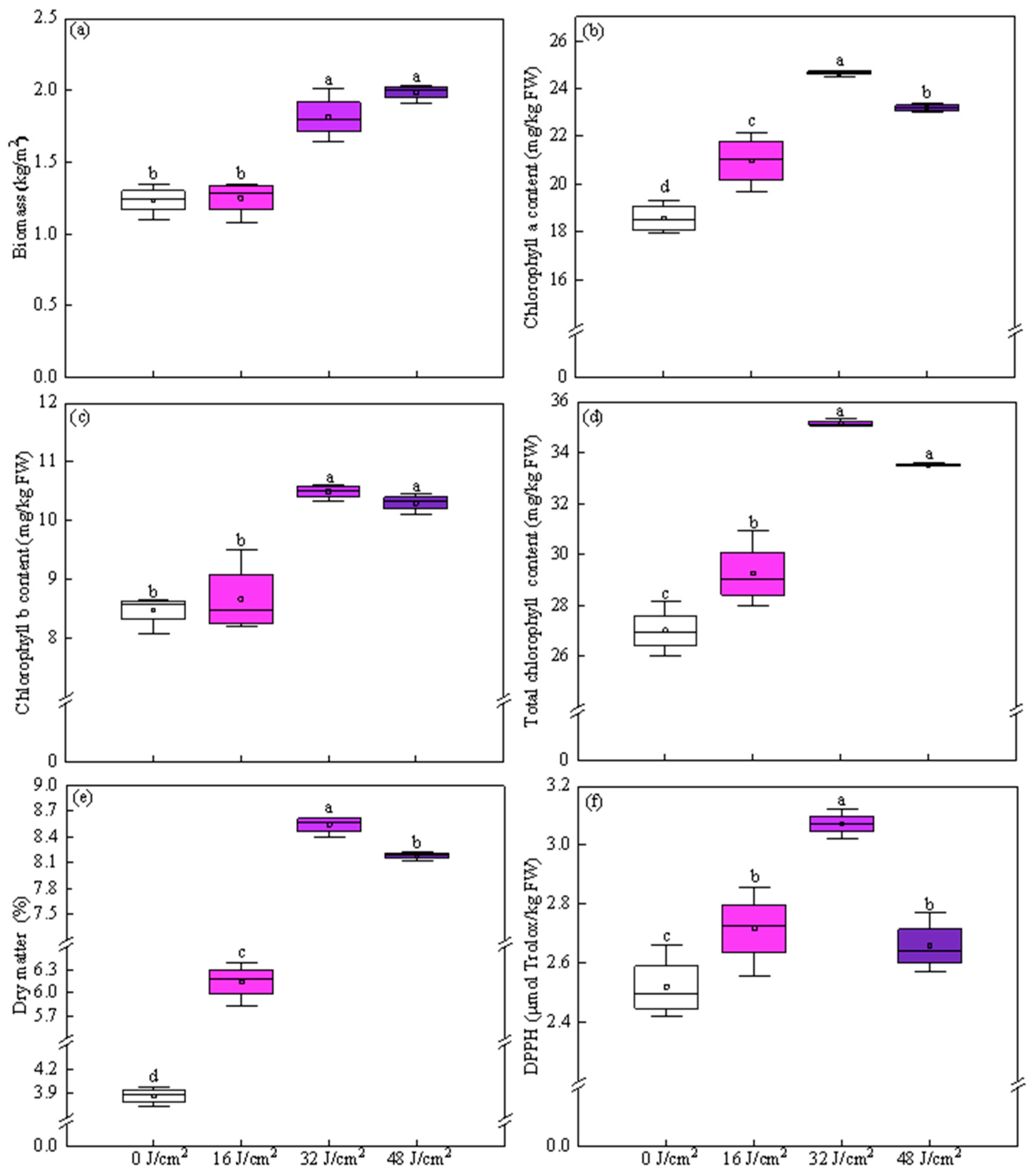

3.1. Selection of Irradiation Dose

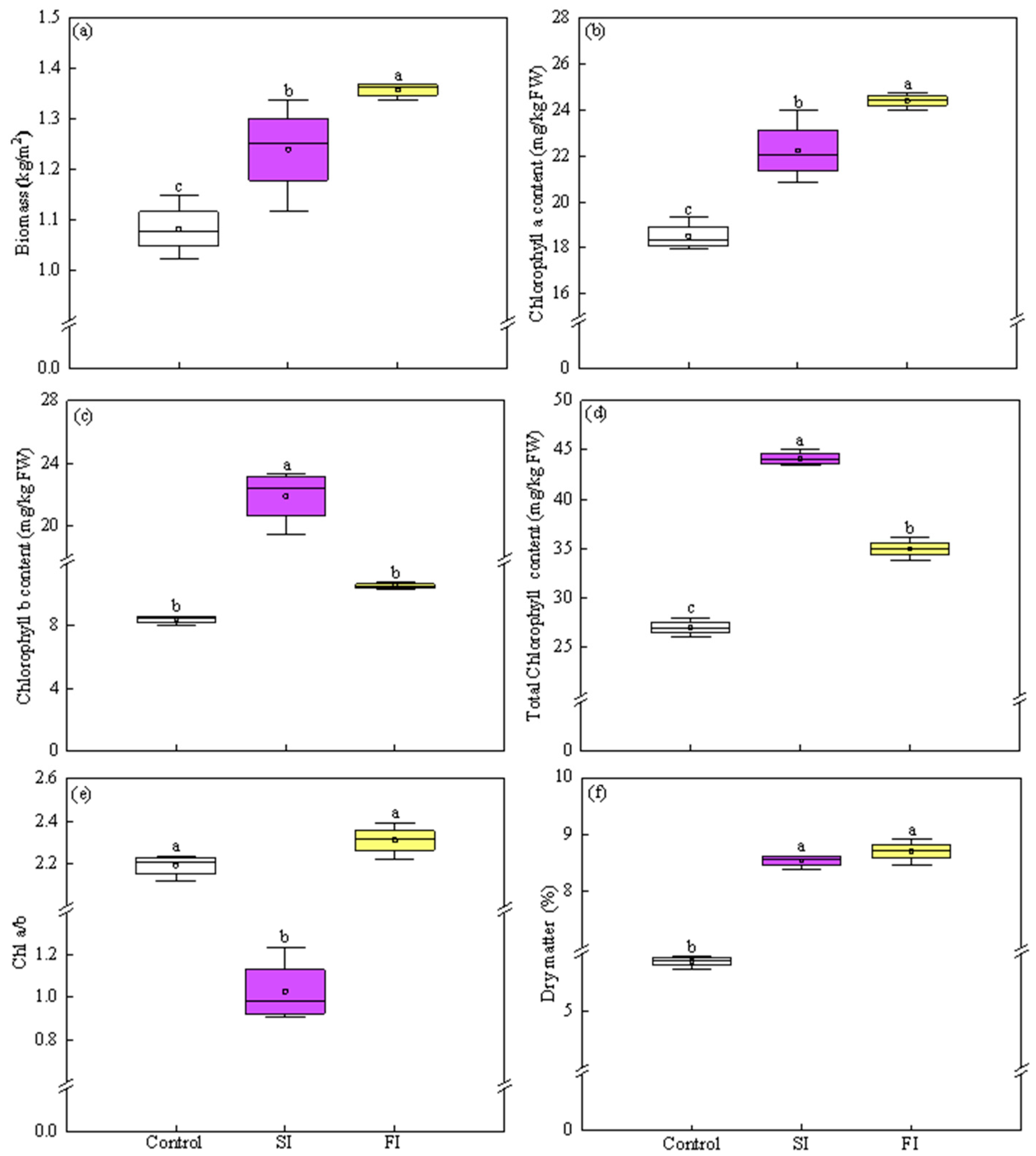

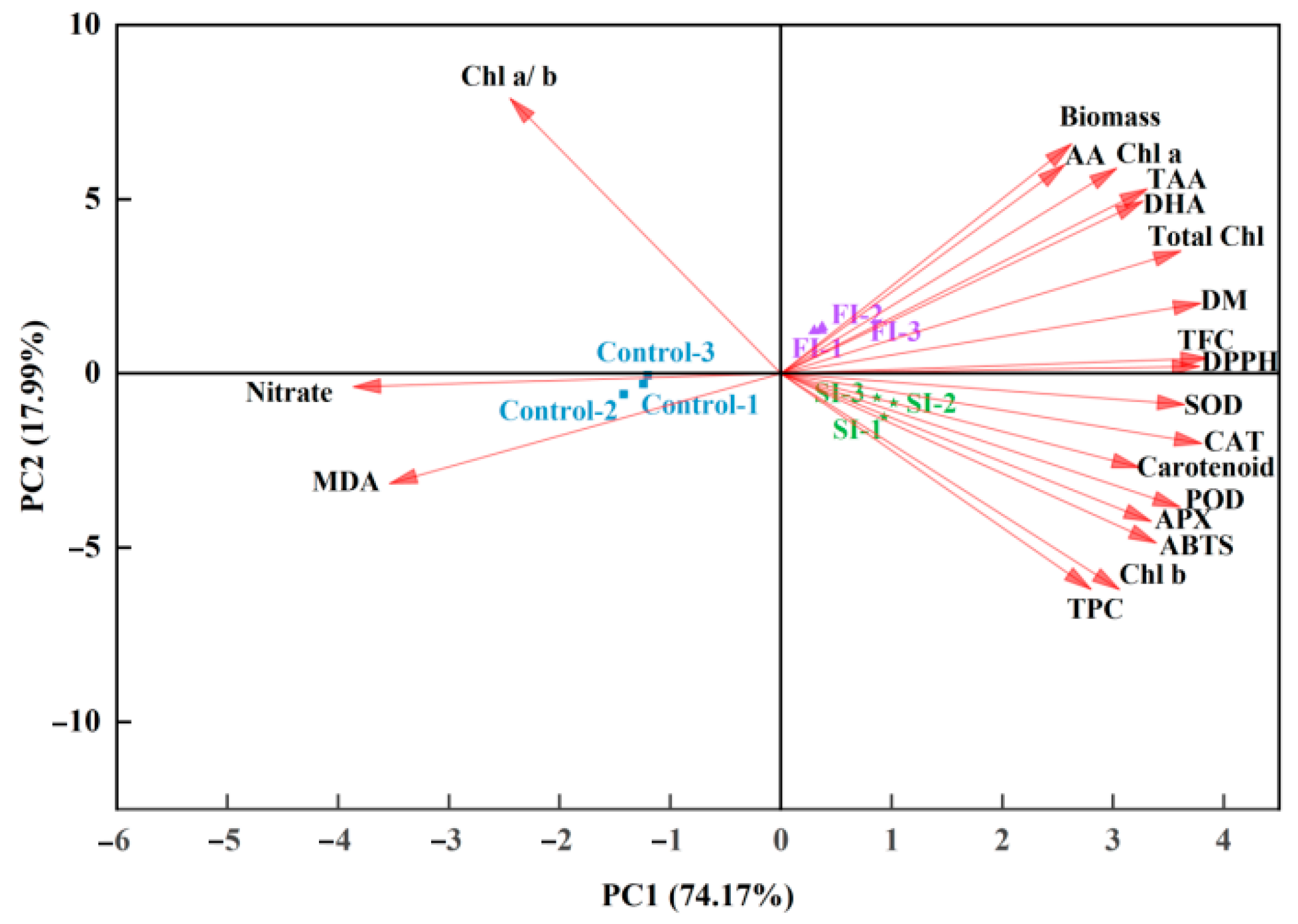

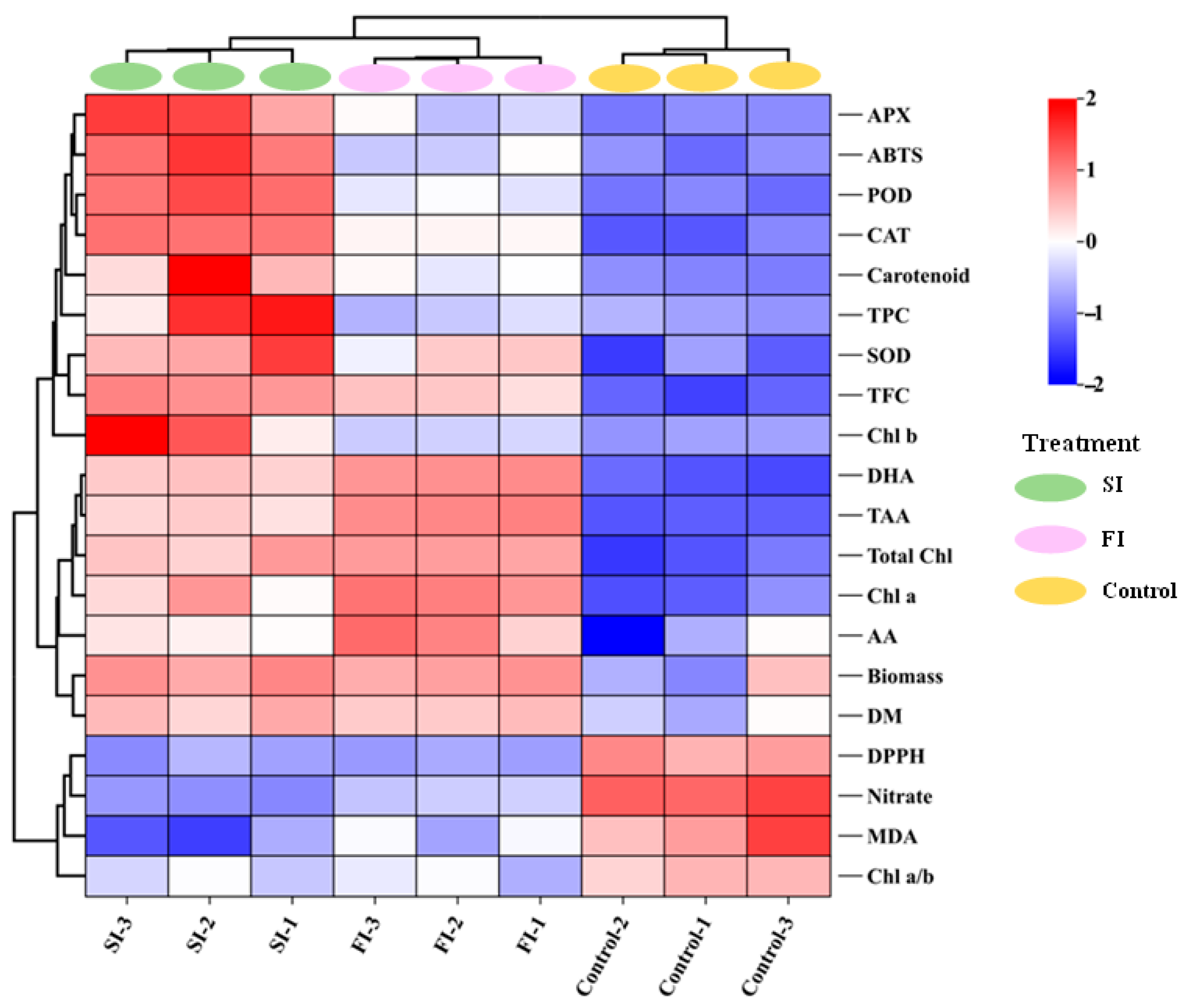

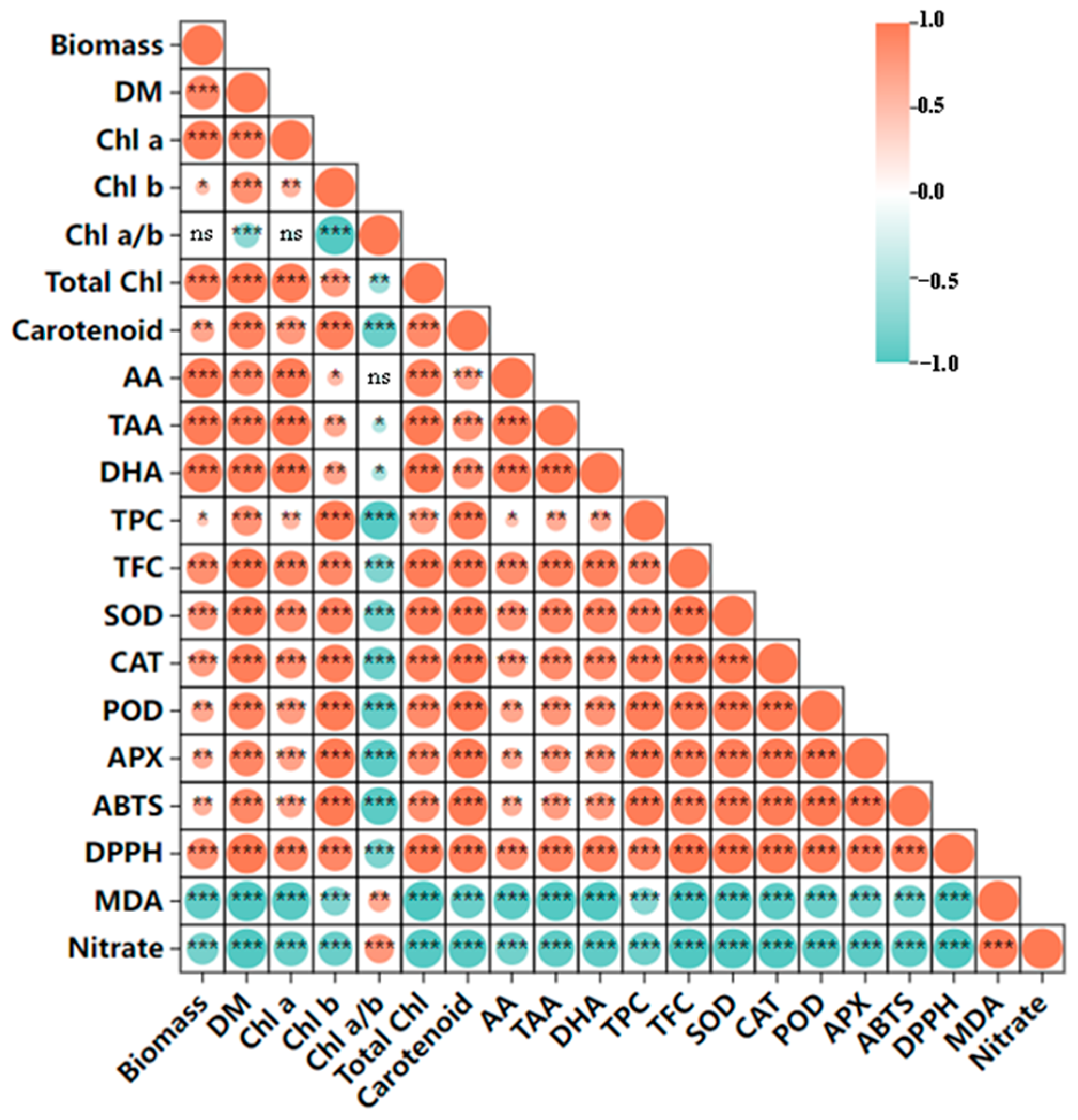

3.2. Effect of Irradiation Patterns on Growth Traits

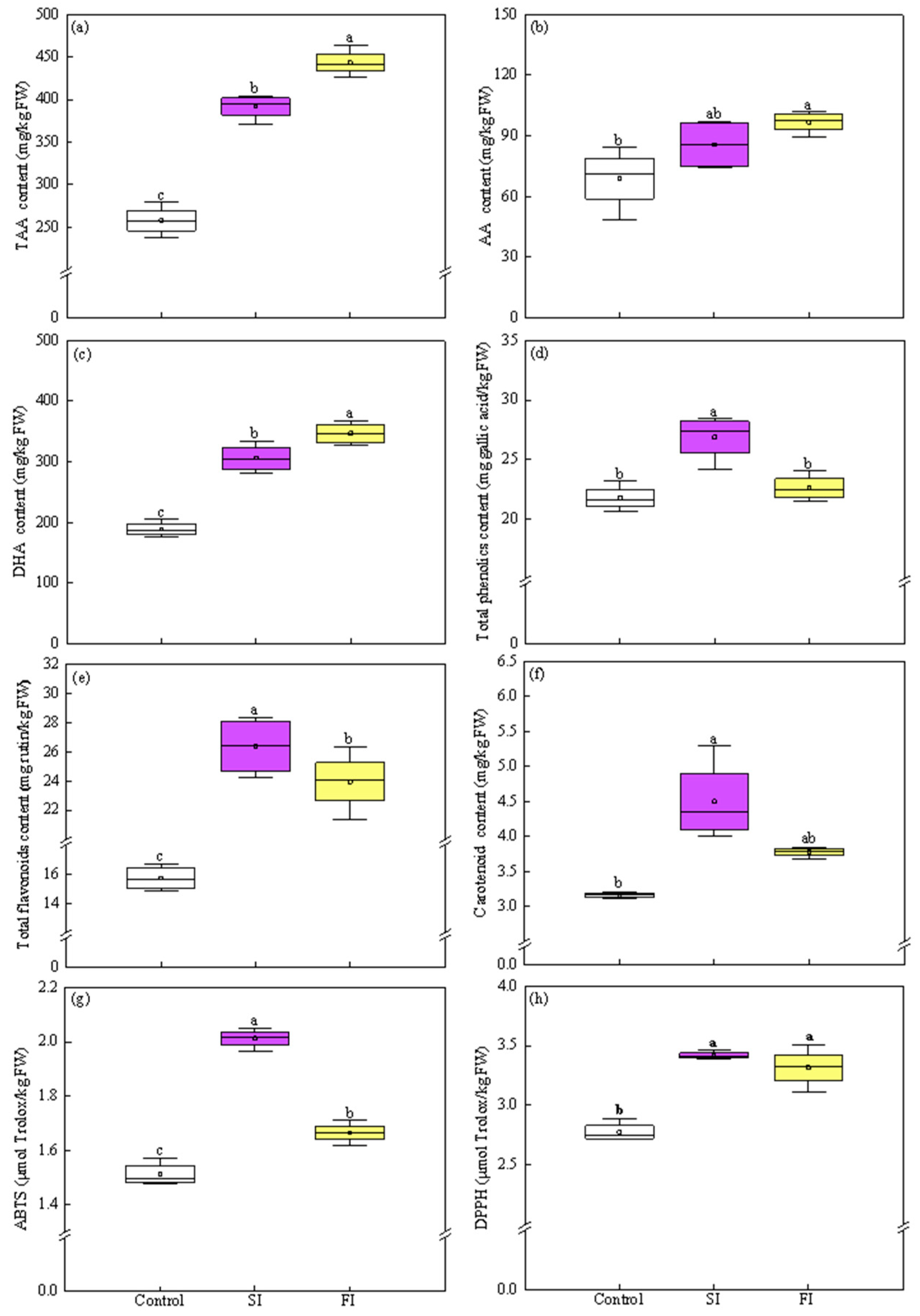

3.3. Effect of Irradiation Pattern on Antioxidants and TAC

3.3.1. TAA, AA, and DHA Content

3.3.2. TPC, TF, and Carotenoids Content

3.3.3. TAC Values

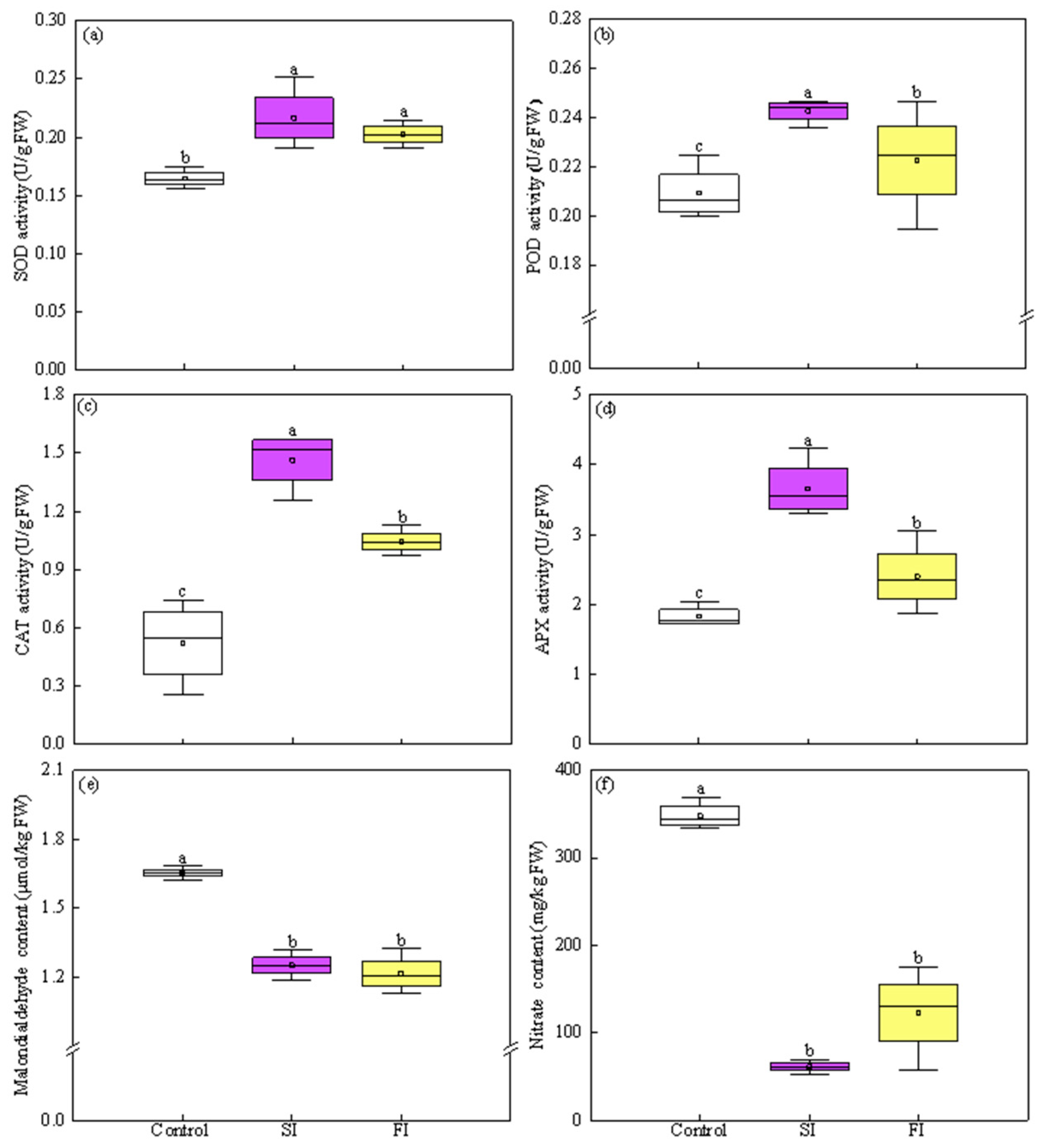

3.4. Effect of Irradiation Pattern on Antioxidant Enzymes and MDA

3.5. Effect of Irradiation Pattern on Nitrate Content

4. Discussion

4.1. UVA-LED Promotes the Growth and Total Antioxidant Capacity of CCM, but Strongly Dose-Dependent

4.2. Both FI and SI Positively Affect Growth and Antioxidant Components, but Through Distinct Mode of Actions

4.3. UVA-LED Improves the Antioxidant Property of CCM via Accumulating the Antioxidants

4.4. The Nitrate Content in CCM Is Far Below the Threshold of Trade Limitation and Reduced by UVA-LED Regardless of Irradiation Patterns

4.5. Research Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turner, E.R.; Luo, Y.; Buchanan, R.L. Microgreen nutrition, food safety, and shelf life: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 85, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artes-Hernandez, F.; Castillejo, N.; Martinez-Zamora, L. UV and Visible Spectrum LED Lighting as Abiotic Elicitors of Bioactive Compounds in Sprouts, Microgreens, and Baby Leaves-A Comprehensive Review including Their Mode of Action. Foods 2022, 11, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, S.A.; Shah, M.A.; Mir, M.M. Microgreens: Production, shelf life, and bioactive components. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2730–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research and Markets. Microgreens Market 2025–2033. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/microgreen#tag-pos-1 (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Brazaityte, A.; Virsile, A.; Jankauskiene, J.; Sakalauskiene, S.; Samuoliene, G.; Sirtautas, R.; Novickovas, A.; Dabasinskas, L.; Miliauskiene, J.; Vastakaite, V.; et al. Effect of supplemental UV-A irradiation in solid-state lighting on the growth and phytochemical content of microgreens. Int. Agrophys. 2015, 29, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloggia, F.P.; Bafumo, R.F.; Ramirez, D.A.; Maza, M.A.; Camargo, A.B. Brassicaceae microgreens: A novel and promissory source of sustainable bioactive compounds. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neugart, S.; Schreiner, M. UVB and UVA as eustressors in horticultural and agricultural crops. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 234, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Yuk, H.-G.; Khoo, G.H.; Zhou, W. Application of Light-Emitting Diodes in Food Production, Postharvest Preservation, and Microbiological Food Safety. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 14, 719–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdaguer, D.; Jansen, M.A.K.; Llorens, L.; Morales, L.O.; Neugart, S. UV-A radiation effects on higher plants: Exploring the known unknown. Plant Sci. 2017, 255, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.-S.; Nguyen, T.K.L.; Oh, M.-M. Growth and biochemical responses of kale to supplementary irradiation with different peak wavelengths of UV-A light-emitting diodes. Hortic. Environ. Biote. 2022, 63, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazaityte, A.; Virsile, A.; Samuoliene, G.; Vastakaite-Kairiene, V.; Jankauskiene, J.; Miliauskiene, J.; Novickovas, A.; Duchovskis, P. Response of Mustard Microgreens to Different Wavelengths and Durations of UV-A LEDs. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, T.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, J.; Bian, Z.; Wen, X. UVA Radiation Is Beneficial for Yield and Quality of Indoor Cultivated Lettuce. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fanourakis, D.; Tsaniklidis, G.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Yang, Q.; Li, T. Low UVA intensity during cultivation improves the lettuce shelf-life, an effect that is not sustained at higher intensity. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 172, 111376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, T.; Sun, L.; Kong, Y.; Masabni, J.; Niu, G. Short-Term Pre-Harvest Supplemental Lighting with Different Light Emitting Diodes Improves Greenhouse Lettuce Quality. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanindi, A.; Sutjahjo, S.; Aisyah, S.; Purwantari, N. Characteristic morphology and genetic variability of benggala grass (panicum maximum cv purple guinea) through gamma ray irradiated on acid land. J. Ilmu Ternak Dan Veterine 2016, 21, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedea, M.; Castel, A.; Arnalte, M.; Mollera, A.; Munoz, V.; Guedea, F. Single high-dose vs. fractionated radiotherapy: Effects on plant growth rates. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2013, 18, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Silva, M.; Machado, J.; López-Ruiz, R.; Marín-Sáez, J.; Viegas, O.; Faria, M.; Romero-Gonzalez, R.; Garrido-Frenich, A.; Carvalho, S.; Ferreira, I. Hormetic effect of UV-C radiation on red mustard microgreens growth and chemical composition. J. Agr. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Huang, W.; Gao, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhan, L. A novel strategy of using ultraviolet a light emitting diodes (UVA-LED) irradiation extends the shelf-life and enhances the antioxidant property of minimally processed pakchoi (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis). Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Yang, M.H.; Wen, H.M.; Chern, J.C. Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colorimetric methods. J. Food Drug Anal. 2002, 10, 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kampfenkel, K.; Van Montagu, M.; Inze, D. Extraction and determination of ascorbate and dehydroascorbate from plant tissue. Anal. Biochem. 1995, 225, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrauri, J.A.; Sanchez-Moreno, C.; Ruperez, P.; Saura-Calixto, F. Free radical scavenging capacity in the aging of selected red Spanish wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 1603–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, I.; Marschner, H. Magnesium deficiency and high light intensity enhance activities of superoxide dismutase, ascorbate peroxidase, and glutathione reductase in bean leaves. Plant Physiol. 1992, 98, 1222–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibaeva, T.G.; Sherudilo, E.G.; Rubaeva, A.A.; Titov, A.F. Continuous LED Lighting Enhances Yield and Nutritional Value of Four Genotypes of Brassicaceae Microgreens. Plants 2022, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Wu, W.; Chen, H.; Niu, B.; Han, Y.; Fang, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, R.; Gao, H. Nitric oxide treatment delays quality deterioration and enzymatic browning of Agaricus bisporus via reactive oxygen metabolism regulation. Food Front. 2023, 4, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NY/T 1279-2007; Determination of Nitrate Content in Vegetables and Fruits. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2007. (In Chinese)

- Marcelis, L.F.M.; Broekhuijsen, A.G.M.; Meinen, E.; Nijs, E.M.F.M.; Raaphorst, M.G.M. Quantification of the growth response to light quantity of greenhouse grown crops. Acta Hort. 2006, 711, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCree, K. The action spectrum, absorptance and quantum yield of photosynthesis in crop plants. Agr. Meteorol. 1972, 9, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Gao, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, S.; Su, W.; Liu, H. Supplemental UV-A Affects Growth and Antioxidants of Chinese Kale Baby-Leaves in Artificial Light Plant Factory. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, W.R.; Christie, J.M. Phototropins 1 and 2: Versatile plant blue-light receptors. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yu, L.; Liu, L.; Yang, A.; Huang, X.; Zhu, A.; Zhou, H. Effects of Ultraviolet-B radiation on the regulation of ascorbic acid accumulation and metabolism in lettuce. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Hu, J.; Ai, Z.; Pang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhu, M. Light exposure during storage preserving soluble sugar and L-ascorbic acid content of minimally processed romaine lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. var. longifolia). Food Chem. 2013, 136, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Patil, B.; Zhen, S. From ultraviolet-B to red photons: Effects of end-of-production supplemental light on anthocyanins, phenolics, ascorbic acid, and biomass production in red leaf lettuce. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0328303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, T.; Grundy, S.; Yang, Q.; Cheng, R. A Review of Environment Effects on Nitrate Accumulation in Leafy Vegetables Grown in Controlled Environments. Foods 2020, 9, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamaria, P. Nitrate in vegetables: Toxicity, content, intake and EC regulation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Yan, X.-J.; Hu, X.-F.; Yan, L.-J.; Cao, M.-Y.; Zhang, W.-J. Nitrate Quantification in Fresh Vegetables in Shanghai: Its Dietary Risks and Preventive Measures. Int. J. Env. Res. Pub. He. 2022, 19, 14487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.K.; Yang, Q.C.; Qiu, Z.P. Spatiotemporal changes of nitrate and Vc contents in hydroponic lettuce treated with various nitrogen-free solutions. Acta Agr. Scand B-S P 2012, 62, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, X.; He, X.; He, R.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, H. Effects of Pre-Harvest Supplemental UV-A Light on Growth and Quality of Chinese Kale. Molecules 2022, 27, 7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhaelewyn, L.; Van Der Straeten, D.; De Coninck, B.; Vandenbussche, F. Ultraviolet Radiation From a Plant Perspective: The Plant-Microorganism Context. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 597642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ai, J.; Gao, H.; Fan, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Wu, R.; Beyatli, A.; Shi, X.; Nicola, S.; Guo, S.; Suleria, H.A.R.; et al. Preharvest UVA-LED Enhancing Growth and Antioxidant Properties of Chinese Cabbage Microgreens: A Comparative Study of Single Versus Fractionated Irradiation Patterns. Foods 2025, 14, 4092. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234092

Ai J, Gao H, Fan Y, Yuan Q, Wu R, Beyatli A, Shi X, Nicola S, Guo S, Suleria HAR, et al. Preharvest UVA-LED Enhancing Growth and Antioxidant Properties of Chinese Cabbage Microgreens: A Comparative Study of Single Versus Fractionated Irradiation Patterns. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4092. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234092

Chicago/Turabian StyleAi, Junxi, Han Gao, Yamin Fan, Quan Yuan, Ran Wu, Ahmet Beyatli, Xiaoqiang Shi, Silvana Nicola, Shuihuan Guo, Hafiz A. R. Suleria, and et al. 2025. "Preharvest UVA-LED Enhancing Growth and Antioxidant Properties of Chinese Cabbage Microgreens: A Comparative Study of Single Versus Fractionated Irradiation Patterns" Foods 14, no. 23: 4092. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234092

APA StyleAi, J., Gao, H., Fan, Y., Yuan, Q., Wu, R., Beyatli, A., Shi, X., Nicola, S., Guo, S., Suleria, H. A. R., & Zhan, L. (2025). Preharvest UVA-LED Enhancing Growth and Antioxidant Properties of Chinese Cabbage Microgreens: A Comparative Study of Single Versus Fractionated Irradiation Patterns. Foods, 14(23), 4092. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234092