From Ethnobotany to Food Innovation: Applications and Functional Potential of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Morphological, Genetic, and Ecophysiological Diversity

2.1. Morphological Diversity

2.2. Genetic Diversity and Comparative Context

2.3. Ecophysiological Adaptation and Accumulation of Bioactive Substances

2.4. Ecophysiological Diversity

3. Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds

3.1. Macronutrients

3.1.1. Carbohydrates

3.1.2. Proteins

3.1.3. Lipids

3.2. Micronutrients

3.2.1. Minerals

3.2.2. Vitamins

3.3. Bioactive Compounds

3.3.1. Glucosinolates

3.3.2. Phenolic Compounds

3.3.3. Anthocyanins

3.3.4. Other Bioactive Compounds

4. Functional Properties and Biological Activity

4.1. Antioxidant Activity

4.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

4.3. Antiproliferative and Cytotoxic Activities

4.4. Antimicrobial Activity

4.5. Organ and System Protection Activities

5. Processing Technologies and Product Development

5.1. Primary Processing

5.2. Emerging Extraction and Processing Technologies

5.3. Fermented Products

5.4. Bakery and Cereal-Based Products

6. Commercial Perspectives and Sustainability

6.1. Segmentation of Emerging Markets

6.2. Technological Scaling Strategies

6.3. Value Chain Models

6.4. Industrially Scalable Products

7. Current Challenges and Future Research Directions

7.1. Current Challenges and Limitations

7.2. Challenges in Developing Functional Products

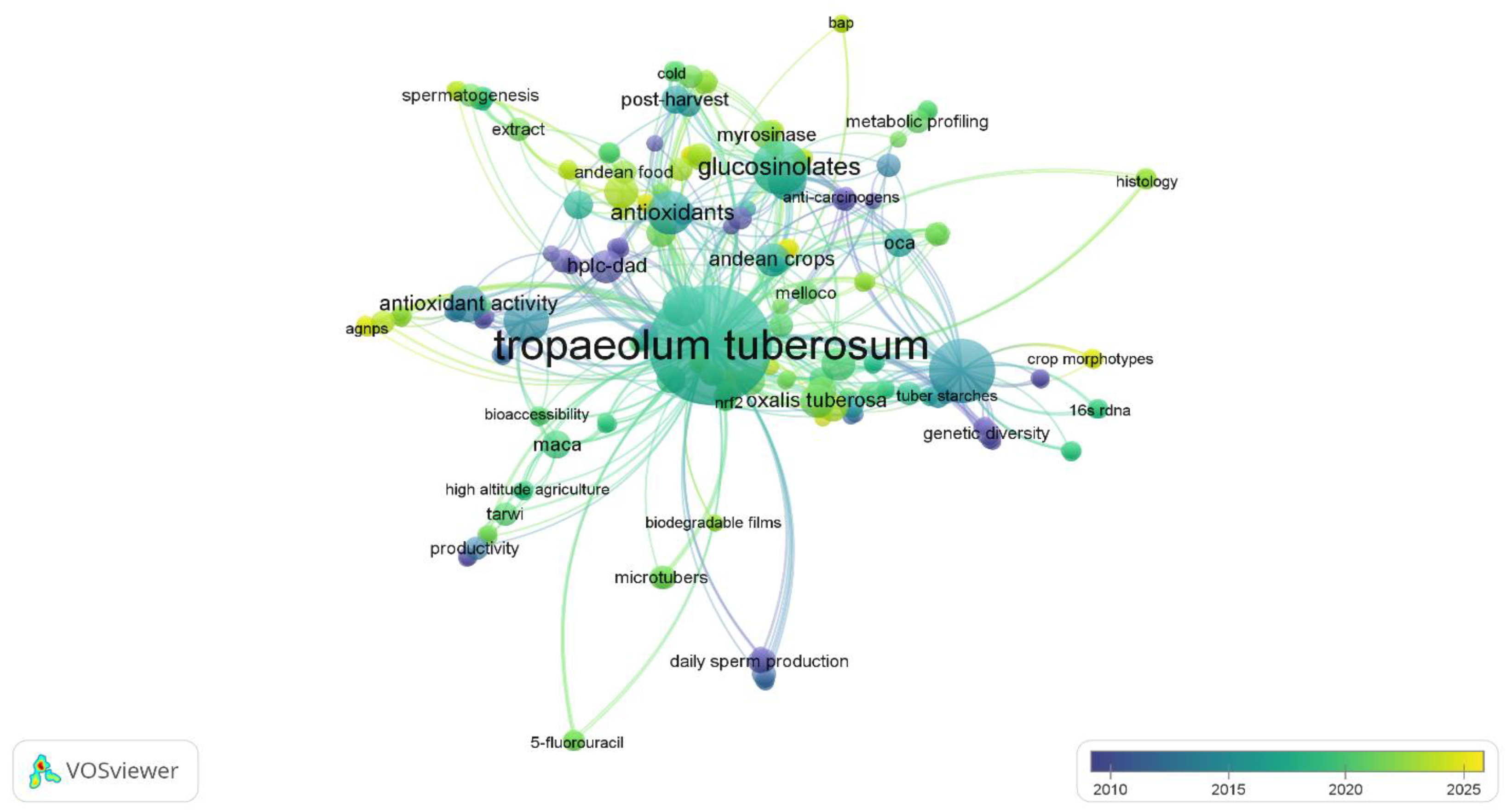

7.3. Research Trends

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS | 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| AFLP | Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism |

| AGE | Advanced Glycation End Products |

| APC | Antioxidant Power Composite Index |

| aPTT | Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time |

| BSA-MGO | Bovine Serum Albumin–Methylglyoxal |

| C3G | Cyanidin-3-Glucoside Equivalents |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Units |

| CI | Combination Index |

| d.b. | D.b. |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| EaF | Ethyl Acetate Fraction |

| 5-FU | 5-Fluorouracil |

| FRAP | Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power |

| GAE | Gallic Acid Equivalents |

| GSL | Glucosinolates |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| HPLC-DAD/MS | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detector and Mass Spectrometry |

| ISSR | Inter-Simple Sequence Repeats |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoproteins |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2–Related Factor 2 |

| ORAC | Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity |

| PT | Prothrombin Time |

| RAPD | Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA |

| RE | Retinol Equivalents |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SSR | Simple Sequence Repeats |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances |

| TE | Trolox Equivalents |

| TEAC | Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

References

- Choque-Delgado, G.T.; Carpio-Coaguila, D.M.; Cáceres-La Torre, L.D. Peruvian native roots and tubers: Nutritional, functional, and industrial aspects. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Portillo, S.; del Rosario Salazar-Sánchez, M.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R. Andean Tubers, Morphological Diversity, and Agronomic Management: A Review. Plant Sci. Today 2023, 10, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, A.; Andrade, N.J.P.; Sørensen, M. Traditional Uses, Processes, and Markets: The Case of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruíz & Pav.). In Traditional Products and Their Processes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; Volume 4, pp. 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, O.R.; Duran, E.; Arbizu, C.; Ortega, R.; Roca, W.; Potter, D.; Quiros, C.F. Pattern of Genetic Diversity of Cultivated and Non-Cultivated Mashua, Tropaeolum tuberosum, in the Cusco Region of Perú. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2007, 54, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaza, L.; Tena, V.; Bermejo, P. Local/Traditional Uses, Secondary Metabolites and Biological Activities of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruíz & Pavón). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 247, 112152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantre-López, A.R.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Ascacio-Valdes, J.A.; Salazar-Sánchez, M.d.R.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Nery-Flores, S.D.; Silva-Belmares, S.Y.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R. Andean tubers: Traditional medicine and other applications. Plant Sci. Today 2024, 11, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luziatelli, G.; Sørensen, M.; Jacobsen, S.E. Current Uses of Andean Roots and Tuber Crops in South American Gourmet Restaurants. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 22, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Portillo, S.; Salazar-Sánchez, M.D.R.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R. Sustainable Use of Andean Tubers: Nutritional, Bioactive, and Functional Properties. In Sustainable Environment and Health: Practical Strategies; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acurio, L.; Salazar, D.; Montero, C.M.; Matas, A.; Debut, A.; Vizuete, K.; Martínez-Monzó, J.; García-Segovia, P.; Igual, M. Viability of 3D Printing of Andean Tubers and Tuberous Root Puree. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 38, 101025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Barreto, F.F.; Sánchez, C.E.V. Microencapsulation of Purple Mashua Extracts Using Andean Tuber Starches Modified by Octenyl Succinic Anhydride. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 2022, 8133970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pissard, A.; Arbizu, C.; Ghislain, M.; Bertin, P. Influence of Geographical Provenance on the Genetic Structure and Diversity of the Vegetatively Propagated Andean Tuber Crop, Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum), Highlighted by Intersimple Sequence Repeat Markers and Multivariate Analysis Methods. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2008, 169, 1248–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Parra, M.; Pomboza-Tamaquiza, P.; Buenaño-Sanchez, M.; Guevara-Freire, D.; Chasi-Vizuete, P.; Vásquez-Freitez, C.; Pérez-Salinas, M. Morphology, Phenology, Nutrients and Yield of Six Accessions of Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz y Pav (Mashua). Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2018, 21, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pilar Márquez-Cardona, M.; Fonseca Hernández, L.R. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Cubios (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz & Pavón) Collected in Two Municipalities in Boyaca—Colombia. Univ. Sci. 2024, 29, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, G.; Carhuaz, R.; Davalos, J.; Andía Ayme, V. Use of Rita® Temporary Sion System to Obtain Microtubers of Several Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz & Pavón) Morphotypes. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2020, 23, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malice, M.; Bizoux, J.P.; Blas, R.; Baudoin, J.P. Genetic Diversity of Andean Tuber Crop Species in the in Situ Microcenter of Huanuco, Peru. Crop Sci. 2010, 50, 1915–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behar, H.; Reategui, O.; Liviac, D.; Arcos, J.; Best, I. Phenolic Compounds and in Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Six Accessions of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum R. & P.) from Puno Region, Peru. Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellin 2021, 74, 9707–9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.; Aguilar-Galvez, A.; García-Ríos, D.; Chirinos, R.; Limaymanta, E.; Pedreschi, R. Postharvest Storage and Cooking Techniques Affect the Stability of Glucosinolates and Myrosinase Activity of Andean Mashua Tubers (Tropaeolum tuberosum). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 2387–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirinos, R.; Pedreschi, R.; Rogez, H.; Larondelle, Y.; Campos, D. Phenolic Compound Contents and Antioxidant Activity in Plants with Nutritional and/or Medicinal Properties from the Peruvian Andean Region. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 47, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Galvez, A.; Pedreschi, R.; Carpentier, S.; Chirinos, R.; García-Ríos, D.; Campos, D. Proteomic Analysis of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum) Tubers Subjected to Postharvest Treatments. Food Chem. 2020, 305, 125485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condori, B.; Mamani, P.; Botello, R.; Patiño, F.; Devaux, A.; Ledent, J.F. Agrophysiological Characterisation and Parametrisation of Andean Tubers: Potato (Solanum sp.), Oca (Oxalis tuberosa), Isaño (Tropaeolum tuberosum) and Papalisa (Ullucus tuberosus). Eur. J. Agron. 2008, 28, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.C.; Higuera, B.L. Glucosinolate Composition of Colombian Accessions of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruíz & Pavón), Structural Elucidation of the Predominant Glucosinolate and Assessment of Its Antifungal Activity. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4702–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, O.R.; Kliebenstein, D.J.; Arbizu, C.; Ortega, R.; Quiros, C.F. Glucosinolate Survey of Cultivated and Feral Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruíz & Pavón) in the Cuzco Region of Peru. Econ. Bot. 2006, 60, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A.; Peña-Rojas, G.; Paredes-Avila, L.E.; Andía-Ayme, V.; Torres-Contreras, A.M.; Herrera-Calderon, O. Phytochemical Characterization of Twenty-Seven Peruvian Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruíz & Pavón) Morphotypes and the Effect of Postharvest Methyl Jasmonate Application on the Accumulation of Antioxidants. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Marroquín, L.A.; Yucra-Condori, H.R.; Gárate, J.; Mendoza, C.; Deflorio, E. Effect of Heat Processing on Bioactive Compounds of Dehydrated (Lyophilized) Purple Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum). Sci. Agropecu. 2023, 14, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillajo, J.; Bravo-Vásquez, J.; Vernaza, M.G. Efecto de La Cocción y La Concentración de Sal Como Pretratamiento de Chips de Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum) Obtenidos Por Fritura al Vacío. Inf. Tecnológica 2019, 30, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, D.; Arancibia, M.; Ocaña, I.; Rodríguez-Maecker, R.; Bedón, M.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Montero, M.P. Characterization and Technological Potential of Underutilized Ancestral Andean Crop Flours from Ecuador. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acurio, L.; Salazar, D.; García, M.E.; García-Segovia, P.; Martínez-Monzó, J.; Igual, M. Characterization, Mathematical Modeling of Moisture Sorption Isotherms and Bioactive Compounds of Andean Root Flours. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 8, 100752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velásquez-Barreto, F.F.; Bello-Pérez, L.A.; Nuñez-Santiago, C.; Yee-Madeira, H.; Velezmoro Sánchez, C.E. Relationships among Molecular, Physicochemical and Digestibility Characteristics of Andean Tuber Starches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, M.T.; Hernández-Hernández, O.; Moreno, F.J.; Villamiel, M. Andean Tubers Grown in Ecuador: New Sources of Functional Ingredients. Food Biosci. 2020, 35, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coloma, A.; Flores-Mamani, E.; Quille-Calizaya, G.; Zaira-Churata, A.; Apaza-Ticona, J.; Calsina-Ponce, W.C.; Huata-Panca, P.; Inquilla-Mamani, J.; Huanca-Rojas, F. Characterization of Nutritional and Bioactive Compound in Three Genotypes of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz and Pavón) from Different Agroecological Areas in Puno. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 2022, 7550987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Galvez, A.; García-Ríos, D.; Ramírez-Guzmán, D.; Lindo, J.; Chirinos, R.; Pedreschi, R.; Campos, D. In Vitro and In Vivo Biotransformation of Glucosinolates from Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum) by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeta, G.; Miranda-Flores, D.; Bascopé, M.; Peñarrieta, J.M. Characterization of Carotenoids, Proximal Analysis, Phenolic Compounds, Anthocyanidins and Antioxidant Capacity of an Underutilized Tuber (Tropaeolum tuberosum) from Bolivia. Discov. Food 2024, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paucar-Menacho, L.M.; Peñas, E.; Hernandez-Ledesma, B.; Frias, J.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C. A Comparative Study on the Phenolic Bioaccessibility, Antioxidant and Inhibitory Effects on Carbohydrate-Digesting Enzymes of Maca and Mashua Powders. LWT 2020, 131, 109798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choquechambi, L.A.; Callisaya, I.R.; Ramos, A.; Bosque, H.; Mújica, A.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Sørensen, M.; Leidi, E.O. Assessing the Nutritional Value of Root and Tuber Crops from Bolivia and Peru. Foods 2019, 8, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaza, L.; Tena, V.; Serban, A.; Alonso, M.; Rumbero, A. Alkamides from Tropaeolum tuberosum Inhibit Inflammatory Response Induced by TNF–α and NF–ΚB. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 235, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinert, M.E.J.; Martínez, M.M.; Guaranda, I.A.C.; Gaitén, Y.I.G.; Lizama, R.S. Morphological, Chemical Characterization and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Tropaeolum tuberosum (Ruiz & Pav.) Kuntze (Tropaeolaceae) Pink Variety. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/pages/publications/85117564681?origin=scopusAI (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Bayas-Chacha, F.; Bermeo-Sanchez, M.; Herrera-Chavez, B.; Bayas-Morejon, F. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties of Tropaeolum tuberosum Extracts from Ecuador. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2022, 21, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Correa, C.R.; Pazo-Medina, G.I.; Villarreal-La Torre, V.E.; Calderón-Peña, A.A.; Aspajo-Villalaz, C.L.; Cruzado-Razco, J.L.; Del Rosario-Chávarri, J.; González-Siccha, A.D.; Guerrero-Espino, L.M.; González-Blas, M.V.; et al. Wound Healing Activity of Tropaeolum tuberosum-Based Topical Formulations in Mice. Vet. World 2022, 15, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcárcel-Yamani, B.; Rondán-Sanabria, G.G.; Finardi-Filho, F. The Physical, Chemical and Functional Characterization of Starches from Andean Tubers: Oca (Oxalis tuberosa Molina), Olluco (Ullucus tuberosus Caldas) and Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz & Pavón). Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 49, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, S.S.; Taboada, C.; Gonzalez, R.V.; Evans, T.; Damsteegt, V.D.; Kitto, S. In Vitro and Ecuador-Field Performance of Virus-Tested and Virus-Infected Plants of Tropaeolum Tuberosum. Exp. Agric. 2009, 45, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizzolari, A.; Brandolini, A.; Glorio-Paulet, P.; Hidalgo, A. Antioxidant Capacity and Heat Damage of Powder Products from South American Plants with Functional Properties. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2019, 31, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamani, E.F.; Ticona, J.A.; Ponce, W.C.C.; Calizaya, G.Q.; Rojas, F.H.; Paxi, A.C.; Mamani, J.I.; Panca, P.H.; Churata, A.Z. Ancestral Knowledge in Healing the Prostate Based on Isaño (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz y Pavón)|Conocimiento Ancestral En La Curación de La Próstata a Base de Isaño (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz y Pavón). Idesia 2020, 38, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.; Noratto, G.; Chirinos, R.; Arbizu, C.; Roca, W.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L. Antioxidant Capacity and Secondary Metabolites in Four Species of Andean Tuber Crops: Native Potato (Solanum sp.), Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz & Pavón), Oca (Oxalis tuberosa Molina) and Ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus Caldas). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 1481–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Galvez, A.; García-Ríos, D.; Lindo, J.; Ramírez-Guzmán, D.; Chirinos, R.; Pedreschi, R.; Campos, D. Impact of Cold Storage Followed by Drying of Mashua Tuber (Tropaeolum tuberosum) on the Glucosinolate Content and Their Transformation Products. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 7797–7805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela Huamán, C.J.; Gongora Amaut, N.; Dueñas Aragón, M.; Velázquez Rojas, L.; Ramos Calcina, A.; Valenzuela Huamán, N.M. Efecto de Los Extractos Secos Clorofórmico y de Diclorometano de Tropaeolum tuberosum (Ruiz & Pavón) Mashua Sobre Los Parámetros Seminales y Toxicidad Aguda. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Químico-Farm. 2019, 48, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirinos, R.; Campos, D.; Costa, N.; Arbizu, C.; Pedreschi, R.; Larondelle, Y. Phenolic Profiles of Andean Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruíz & Pavón) Tubers: Identification by HPLC-DAD and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activity. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, M.T.; Escribano-Bailón, M.T.; Moreno, F.J.; Villamiel, M.; Dueñas, M. Determination by HPLC-DAD-ESI/MSn of Phenolic Compounds in Andean Tubers Grown in Ecuador. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 84, 103258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirinos, R.; Rogez, H.; Campos, D.; Pedreschi, R.; Larondelle, Y. Optimization of Extraction Conditions of Antioxidant Phenolic Compounds from Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruíz & Pavón) Tubers. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2007, 55, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, E.; Jhunior, R.; Chuquilín-Goicochea, R.; López, J.; Areche, F.; Ruíz, J.; Herrera, A. Obtaining a Natural Dye from Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruíz & Pavón for Application in Yogurt. Bionatura 2023, 8, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Apaza, L.; Peña-Rojas, G.; Andía-Ayme, V.; Durán García, B.; Rumbero Sánchez, A. Anti-Glycative and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Macamides Isolated from Tropaeolum tuberosum in Skin Cells. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 5803–5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirinos, R.; Campos, D.; Warnier, M.; Pedreschi, R.; Rees, J.F.; Larondelle, Y. Antioxidant Properties of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum) Phenolic Extracts against Oxidative Damage Using Biological in Vitro Assays. Food Chem. 2008, 111, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ticona, L.A.; Sánchez, Á.R.; Gonzáles, Ó.O.; Doménech, M.O. Antimicrobial Compounds Isolated from Tropaeolum tuberosum. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 4698–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaza, L.; Arnanz, J.; Serban, A.; Rumbero, Á. Alkaloids Isolated from Tropaeolum tuberosum with Cytotoxic Activity and Apoptotic Capacity in Tumour Cell Lines. Phytochemistry 2020, 177, 112435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva-Revilla, J.; Cárdenas-Valencia, I.; Rubio, J.; Guerra-Castañón, F.; Olcese-Mori, P.; Gasco, M.; Gonzales, G.F. Evaluation of Different Doses of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum) on the Reduction of Sperm Production, Motility and Morphology in Adult Male Rats. Andrologia 2012, 44, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, J.H.; Gonzáles, J.M.; Pino, J.L. Decrease in Spermatic Parameters of Mice Treated with Hydroalcoholic Extract Tropaeolum tuberosum “Mashua”. Rev. Peru. Biol. 2012, 19, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Valencia, I.; Nieto, J.; Gasco, M.; Gonzales, C.; Rubio, J.; Portella, J.; Gonzales, G.F. Tropaeolum tuberosum (Mashua) Reduces Testicular Function: Effect of Different Treatment Times. Andrologia 2008, 40, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaza, L.; Tena Pérez, V.; Serban, A.M.; Sánchez-Corral, J.; Rumbero Sánchez, Á. Design, Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of N -Benzyl Linoleamide Analogues from Tropaeolum tuberosum as NF-κB Inhibitors and Nrf2 Activators. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 11825–11836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirinos, R.; Pedreschi, R.; Cedano, I.; Campos, D. Antioxidants from Mashua (Tropaeolum Tuberosum) Control Lipid Oxidation in Sacha Inchi (Plukenetia volubilis L.) Oil and Raw Ground Pork Meat. J. Food Process Preserv. 2015, 39, 2612–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A. Concept, Mechanism, and Applications of Phenolic Antioxidants in Foods. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Du, L.; Wei, Q.; Lu, M.; Xu, D.; Li, Y. Synthesis and Health Effects of Phenolic Compounds: A Focus on Tyrosol, Hydroxytyrosol, and 3,4-Dihydroxyacetophenone. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Tryniszewski, W.; Sarniak, A.; Wlodarczyk, A.; Nowak, P.J.; Nowak, D. Concentration Dependence of Anti- and Pro-Oxidant Activity of Polyphenols as Evaluated with a Light-Emitting Fe2+-Egta-H2O2 System. Molecules 2022, 27, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sou’od, K.A. Mechanism Engineering of Polyphenol Antioxidants: DFT/TD-DFT Evidence for HAT-SPLET Switching via Targeted Functional Blocking in Curcumin, Quercetin, and Resveratrol Derivatives. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2025, 1254, 115470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Torre, H.; Aliaga-Barrera, I.; Velásquez-Barreto, F.F. Effect of Chlorpropham on the Sprouting and Behavior of Bioactive Compounds in Purple Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruíz & Pavón) During Postharvest Storage. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/pages/publications/85078624579?origin=scopusAI (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Muñoz, A.M.; Jimenez-Champi, D.; Contreras-López, E.; Fernández-Jerí, Y.; Best, I.; Aguilar, L.; Ramos-Escudero, F. Valorization of Extracts of Andean Roots and Tubers and Its Byproducts: Bioactive Components and Antioxidant Activity In Vitro. Food Res. 2023, 7, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merecz-Sadowska, A.; Sitarek, P.; Kucharska, E.; Kowalczyk, T.; Zajdel, K.; Cegliński, T.; Zajdel, R. Antioxidant Properties of Plant-Derived Phenolic Compounds and Their Effect on Skin Fibroblast Cells. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuel, M.; Mesas, C.; Martínez, R.; Ortiz, R.; Quiñonero, F.; Prados, J.; Porres, J.M.; Melguizo, C. Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Potential of Ethanolic Extracts from Moringa oleifera, Tropaeolum tuberosum and Annona cherimola in Colorrectal Cancer Cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeFort, K.R.; Rungratanawanich, W.; Song, B.-J. Contributing Roles of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Hepatocyte Apoptosis in Liver Diseases through Oxidative Stress, Post-Translational Modifications, Inflammation, and Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña-Rojas, G.; Fernández-Núñez, K.J.; Andía-Ayme, V.; Pereda-Medina, A.; Dorca-Fornell, C.; Fernández-Ocaña, A.M. Use of PTC3 as a Pathogen-Growth Inhibitor: Comparative Study with Silver Nanoparticles in in Vitro Propagation of Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz & Pavón “Mashua”. Vegetos 2023, 37, 2647–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Lv, Y.; Zhao, C.; Shi, Y.; Tang, R.; He, L.; Fan, R.; Jia, X. Extraction of Anthocyanins from Purple Sweet Potato: Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Effects in a Rheumatoid Arthritis Animal Model, Mechanistic Studies on Inflammatory Cells, and Development of Exosome-Based Delivery for Enhanced Targeting. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1559874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabuncu, M.; Dulger Altıner, D.; Sahan, Y. In Vitro Biological Activity and Nutritional Evaluation of Purple Potato (Solanum tuberosum L. Var. Vitelotte). BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widowati, W.; Tjokropranoto, R.; Onggowidjaja, P.; Widya Kusuma, H.S.; Wijayanti, C.R.; Marthania, M.; Yati, A.; Rizal, R. Protective Effect of Yacon Leaves Extract (Smallanthus sonchifolius (Poepp.) H. Rob) through Antifibrosis, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antioxidant Mechanisms toward Diabetic Nephropathy. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 18, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhers, I.; Morel, S.; Kongolo, J.; Domingo, R.; Servent, A.; Ollier, L.; Kodja, H.; Petit, T.; Poucheret, P. Immunomodulatory and Antioxidant Properties of Ipomoea Batatas Flour and Extracts Obtained by Green Extraction. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 6967–6985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, M.T.; Moreno, F.J.; Moreno, R.; Villamiel, M.; Hernandez-Hernandez, O. Morphological, Technological and Nutritional Properties of Flours and Starches from Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum) and Melloco (Ullucus tuberosus) Cultivated in Ecuador. Food Chem. 2019, 301, 125268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acurio, L.; Salazar, D.; García-Segovia, P.; Martínez-Monzó, J.; Igual, M. Third-Generation Snacks Manufactured from Andean Tubers and Tuberous Root Flours: Microwave Expansion Kinetics and Characterization. Foods 2023, 12, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triana, M.M.; López-Molinello, A.; Prieto, L.; Povea, I.; Sáenz, S. Development of an Alcoholic Beverage from Cubio (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz & Pav.) Using Saccharomyces bayanus Yeast. Ingenieria 2024, 29, e21059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acurio, L.; Salazar, D.; Castillo, B.; Santiana, C.; Martínez-Monzó, J.; Igual, M. Characterization of Second-Generation Snacks Manufactured from Andean Tubers and Tuberous Root Flours. Foods 2024, 13, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, A.R.; Cuenca, M. Evaluation of Lactic Acid Fermentation in a Dairy and Non-Dairy Beverage Using Two Commercial Starter Cultures. Vitae 2022, 29, 347447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, D.; Arancibia, M.; Silva, D.R.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Montero, M.P. Exploring the Potential of Andean Crops for the Production of Gluten-Free Muffins. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre Forero, S.E.; Piraneque Gambasica, N.V.; Perez Mojica, I. Andean Tuber Production System in Boyacá, Colombia. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural 2012, 9, 257–273. [Google Scholar]

- Daza, L.D.; Umaña, M.; Simal, S.; Váquiro, H.A.; Eim, V.S. Non-Conventional Starch from Cubio Tuber (Tropaeolum tuberosum): Physicochemical, Structural, Morphological, Thermal Characterization and the Evaluation of Its Potential as a Packaging Material. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 221, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pico, C.; De la Vega, J.; Tubón, I.; Arancibia, M.; Casado, S. Nanoscopic Characterization of Starch Biofilms Extracted from the Andean Tubers Ullucus tuberosus, Tropaeolum tuberosum, Oxalis tuberosa, and Solanum tuberosum. Polymers 2022, 14, 4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña Beraun, S.R.; Parraga Melgarejo, N.; Alvarez Tolentino, D.M. Efecto de La Suplementación Con Harina de Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum) y Tarwi (Lupinus mutabilis) Sobre La Respuesta Productiva y Composición Nutricional de Cuyes (Cavia porcellus). Rev. Investig. Vet. Perú 2021, 32, e18430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Rojas, G.; Carhuaz-Condori, R.; Andía-Ayme, V.; Leon, V.A.; Herrera-Calderon, O. Improved Production of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum) Microtubers MAC-3 Morphotype in Liquid Medium Using Temporary Immersion System (TIS-RITA®). Agriculture 2022, 12, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Parra, M.; Lalaleo, L.; Pomboza-Tamaquiza, P.; Ramírez-Estrada, K.; Becerra-Martínez, E.; Hidalgo, D. From Morphological Traits to the Food Fingerprint of Tropaeolum Tuberosum through Metabolomics by NMR. LWT 2020, 119, 108869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daga, J.G.; Gaviño, J.P.; Dávila, R.A.; Quiroz, J.F.; Cortez, C.B.; Velásquez, P.P.; Oshige, B.S. Effect of Tropaeolum tuberosum “Mashua” (Tropaeolaceae) on Gene Expression Related To Spermatogenesis in Mouse. Rev. Fac. Med. Hum. 2023, 23, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal Huamán, F.G.; Sánchez Charcape, M.; Castro Mattos, M.; Gómez Rutti, Y. Conocimientos y Consumo de Alimentos Andinos En Universitarios Del Perú. Nutrición Clínica y Dietética Hospitalaria 2024, 44, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Daga, J.; Alvis-Dávila, R.; Pino-Gaviño, J.L.R.; Iziga-Goicochea, R. Effect of “mashua” Tropaeolum tuberosum’ Aqueous Extract in Sperm Quality and Its Implication in the Preimplantacional Development of Mouse Embryos. Rev. Fac. Med. Hum. 2020, 20, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.L.; Mattoo, A.K. Reducing Bitterness in Cucurbitaceae and Glucosinolates in Brassicaceae. In Next Generation Food Crops for Human Health; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, W.; Fan, X. An Improved Spectrophotometric Method for Quantificationally Measuring Total Glucosinolates Content in Tumorous Stem Mustard (Brassica juncea Var. Tumida). Food Anal. Methods 2024, 17, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska-Zimny, K.; Beneduce, L.; Sikorska-Zimny, K.; Beneduce, L. The Metabolism of Glucosinolates by Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Reported Range (d.b) | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | 6.96–18.25 | g/100 g | [10,12,29,30,39,40] |

| Total carbohydrates | 73.79–85.8 | g/100 g | [10,30] |

| Total sugars | 27.70–53.5 | g/100 g | [29,39,41] |

| Lipids | 0.92–1.67 | g/100 g | [10,29,32,39] |

| Dietary fiber | 0.7–15.59 | g/100 g | [10,39] |

| Energy | 343.66–440 | kJ/100 g | [12,26,32,42] |

| Compound | Reported Range (d.b.) | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | 0.65–446 | mg/100 g | [17,23,30] |

| Total carotenoids | 0.1–8.6 | mg/100 g | [17,23,29] |

| β-carotene (Provit. A) | 1.39–9.67 | mg/100 g | [34] |

| Calcium (Ca) | 50–90 | mg/100 g | [29,34] |

| Potassium (K) | 990–3250 | mg/100 g | [12,29,30,34] |

| Phosphorus (P) | 420–730 | mg/100 g | [12,34] |

| Zinc (Zn) | 2.95 | mg/100 g | [34] |

| Compound | Reported Range (d.b.) | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total glucosinolates | 27–9660 | µmol/100 g | [17,21,22,23,34] |

| Total polyphenols | 116–1630 | mg GAE/100 g | [18,23,30] |

| Caffeic acid | ≈888 (as glycoside) | mg/100 g | [33] |

| Total anthocyanins | 13–148,901 | mg C3G/100 g | [18,30] |

| Rutin | 144 | mg/100 g | [33] |

| Quercetin | 0.11–7.6 | mg/100 g | [16,48] |

| Biological Activity | Active Compounds | Main Results | Variety/Extraction | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant | Proanthocyanidins, flavan-3-ols, and anthocyanins | LDL inhibition: metal-catalyzed stability (Cu2+) extended by flavan-3-ol-rich fractions Anthocyanins retain activity despite limited bioaccessibility and moderately inhibit carbohydrate digestion. | Purple accessions: purified extracts | [33,42,46,51] |

| Anti-glycation (AGEs) | Macamides (S-N-(α-methylbenzyl)-oleamide/linoleamide) | BSA–MGO inhibition: 3.39–8.53%. AGE degradation: 6.58–18.08%. → Specific activity not described in the narrative and relevant to metabolic processes. | Isolated compounds | [50] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Alkamides, macamides, and anthocyanins | Potent activation of Nrf2 by synthetic analog (0.03 nM). NF-κB inhibitory activity documented in topical extracts (histological support). | Ethanolic extracts and synthetic compounds | [35,38,52,53] |

| Antiproliferative/cytotoxic | Isothiocyanates derived from benzyl glucosinolate | Reversible spermatotoxic effects linked to isothiocyanate covalent reactivity (3.7 g/100 g). → Distinctive result of mashua compared with other tubers. | Aqueous extracts | [5,54,55,56] |

| Neuroprotective | N-benzyl linoleamide and analogs | Nrf2 activation with EC50 of 15.95–21.7 nM The most reactive analog activates Nrf2 at 0.03 nM (non-redundant due to extraordinary potency). | Synthetic and natural derivatives | [57] |

| Cardioprotective/hepatoprotective | β-sitosterol, phytosterols, triterpenoids, ethyl acetate fraction | EaF: high antioxidant capacity 200.2 µmol TE/mL and 22.2 mg GAE/mL (key metric for hepatoprotection). Evidence of reduced angiogenesis (not detailed in the narrative). | Lipophilic extracts and EaF | [36,58] |

| Technology | Application | Optimized Parameters | Main Outcome/Functional Benefit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction | Anthocyanin extraction | 48 °C, 33.93% ethanol, 20 min | Maximum yield of anthocyanins and polyphenols; high antioxidant capacity. | [49] |

| Microencapsulation (Spray-drying) | Stabilization of the extracts | 160 °C inlet temperature, 2% OSA starch | High encapsulation efficiency, low hygroscopicity, and low water activity. | [10] |

| Freeze-Drying | Dehydration/Flour | Low temperature/vacuum | Retention of >80% vitamin C; preservation of glucosinolate profile | [24] |

| Extrusion | Functional Snacks (2G/3G) | 20% flour substitution | Increased dietary fiber and phenolic content; minimal nutritional degradation. | [74] |

| 3D Printing | Personalized Food | Pretreatment with cooked puree | Optimal viscoelasticity (G′ > G″) and shape fidelity due to starch retrogradation. | [9] |

| Commercial Sector | Market Opportunities | Limiting Barriers | Viability Indicators | Implementation Strategies | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premium Functional Ingredients | Segmentation of purple is yellow varieties; R2 = 0.7 color–phenolic correlation | Inadequate regulatory frameworks for nutraceuticals | Tt-23: 220.83 ± 0.42 mg GAE/100 g; variability, 2.73–6.825 mg/g d.b. | Geographical origin and industrial visual classification | [16,26,30,33] |

| Natural industrial colorants | Synthetic dye substitution; stability of 3D printing; cosmetology applications | Competition with established dyes and lack of commercialization | Validated dimensional stability; stable and visually appealing natural pigments | Classification of Exotic, Organic, and Natural Products as Consumption Incentives | [74,79] |

| Mass of processed foods consumed | Snacks (71–84% porosity), flours (>80% acceptance), beverages (pH 3.9, >8 log CFU/mL, +38% antioxidant activity) | Consumer education, limited distribution, and uncommon organoleptic properties | Compliance with INEN (<40% fat); 60-day stability; wine 9.5% v/v alcohol; yogurt +6% higher acceptability | Partial substitution in established and differentiated formulations | [25,26,49,74,75,77] |

| Biodegradable packaging | Sustainable plastics alternative; high transparency; synthetic additive replacement | Scaling of starch extraction and production costs | Satisfactory barrier properties and adequate thermal stability | Integration into SSCs and technological partnerships | [80,81] |

| Extractive technologies | UAE: 251 mg GAE/100 g, DPPH >85%; superior time–energy efficiency | Protocol standardization, specialized purification, and methodological heterogeneity | Freeze-drying: >60-day bioactivity; 35–80% efficiency, >75% retention | Industrial technology transfer and site-specific optimization | [10,49,75] |

| Animal feed | 25% mashua supplementation improves productivity; excellent feed for cooked pigs | Undervalued feed rations; traditional management increases costs | Significant effect on carcass fat content (p < 0.05); O. tuberosa leaves as bovine forage | Replacement of soy and maize due to their high nutritional value and exploitation of their nutritional properties | [79,82] |

| Germplasm conservation | SIT-RITA® micropropagation, genetic diversity conservation, and scalable production | Expansion of germplasm banks and limited exchange of protocols | Virus-free microtubers; efficient seed systems; studied 27 morphotypes | Regional cooperation among Andean countries; development of appropriate technologies; availability of germplasm | [7,32,64,83] |

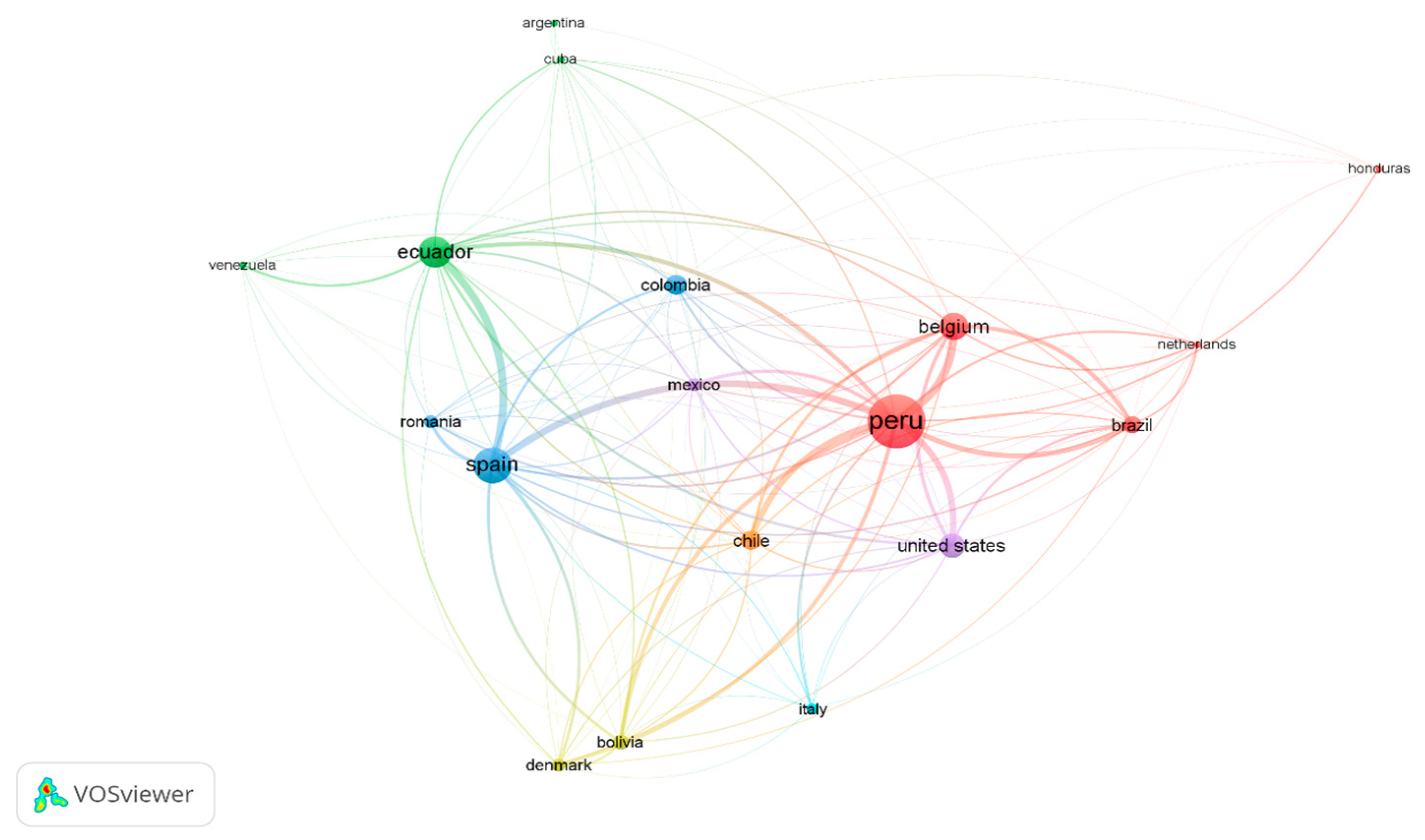

| International markets | Peruvian scientific leadership (48 documents, 1047 citations); strategic collaborations; New Zealand demand for scientific leadership | Limited availability, regulatory entry barriers, and lack of awareness among consumers | Perú–Belgium–Spain–Brazil partnerships; available germplasm; genetic improvement of species | Research–development–commercialization networks, clinical validation, and strategic provincial alliances | [64,79,84] |

| Identified Challenge | Evidence/Observed Limitation | Proposed Research Line |

|---|---|---|

| Variability in Results Reporting | Values reported on fresh vs. d.b.; non-standard units | Analytical protocols on a d.b. using SI units |

| Methodological heterogeneity in bioactive compound determination | Different techniques (spectrophotometry vs. HPLC) yield poorly comparable results | Harmonized methodologies and inter-laboratory validation |

| Lack of clinical trials | Evidence Limited to In Vitro and Animal Models | Human clinical studies on bioavailability and safety |

| Scarce postharvest information | Limited evidence on the stability of bioactive compounds during storage and transport | Kinetics of vitamin C, anthocyanins, and glucosinolate degradation |

| Poorly scaled emerging processes | Technologies, such as microencapsulation and 3D printing, are tested only at the laboratory level. | Validation at pilot and industrial scales with cost-effectiveness assessment |

| Low sensory acceptance | Bitterness and astringency associated with glucosinolate use | Applying partial detoxification techniques and blending with other ingredients |

| Insufficient integration into value chains | Limited articulation among Andean producers, industry, and the global market | Designing inclusive business models with traceability and certification |

| Poorly documented environmental impact | Lack of life cycle analysis in cultivation and processing | Development of studies on sustainability and carbon footprint |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vera, W.; Quevedo-Olaya, J.L.; Minchán-Velayarce, H.; Samaniego-Rafaele, C.; Rodríguez-León, A.; Salvador-Reyes, R.; Quispe-Santivañez, G.W. From Ethnobotany to Food Innovation: Applications and Functional Potential of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum). Foods 2025, 14, 4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234091

Vera W, Quevedo-Olaya JL, Minchán-Velayarce H, Samaniego-Rafaele C, Rodríguez-León A, Salvador-Reyes R, Quispe-Santivañez GW. From Ethnobotany to Food Innovation: Applications and Functional Potential of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum). Foods. 2025; 14(23):4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234091

Chicago/Turabian StyleVera, William, Jhonsson Luis Quevedo-Olaya, Hans Minchán-Velayarce, César Samaniego-Rafaele, André Rodríguez-León, Rebeca Salvador-Reyes, and Grimaldo Wilfredo Quispe-Santivañez. 2025. "From Ethnobotany to Food Innovation: Applications and Functional Potential of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum)" Foods 14, no. 23: 4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234091

APA StyleVera, W., Quevedo-Olaya, J. L., Minchán-Velayarce, H., Samaniego-Rafaele, C., Rodríguez-León, A., Salvador-Reyes, R., & Quispe-Santivañez, G. W. (2025). From Ethnobotany to Food Innovation: Applications and Functional Potential of Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum). Foods, 14(23), 4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234091