Mechanism and Potential of Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction for Constructing Green Production System for Lipids and Proteins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cell Structure of Oilseed Crops

2.1. Cell Wall

2.2. Oil Body

3. Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction Technology

3.1. Key Process Parameters in AEE

3.1.1. Enzyme Type

3.1.2. Enzyme Concentration

3.1.3. Reaction Time

3.2. Physical Integration AEE Technology

3.2.1. Ultrasonic Integration AEE

3.2.2. Microwave Integration AEE

3.2.3. High Hydrostatic Pressure Integration AEE

3.2.4. Pulsed Electric Field Integration AEE

3.2.5. Comparison of Physical Technologies Integrated with AEE

| Technology | Efficiency (Typical Oil Yield Improvement) | Key Advantages | Critical Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | 10–25% | Effective for hard-walled materials; rapid | High energy consumption; potential for protein/peptide degradation; probe erosion at scale | [79,80,81,82] |

| Microwave | 15–30% | Rapid, uniform heating; high efficiency | High energy consumption; potential for protein/peptide degradation; probe erosion at scale | [83,84,85,86] |

| High hydrostatic pressure | 5–20% | Excellent for preserving thermo-labile compounds | Extremely high capital cost; batch processing limits throughput | [87,88,89] |

| Pulsed Electric Field | 10–25% | Low thermal load, energy-efficient for liquids | Limited efficacy on dry or high-fat materials; electrode fouling | [90,91,92] |

3.3. Economic and Environmental Benefits

3.3.1. Enzyme Recycling Strategies

3.3.2. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

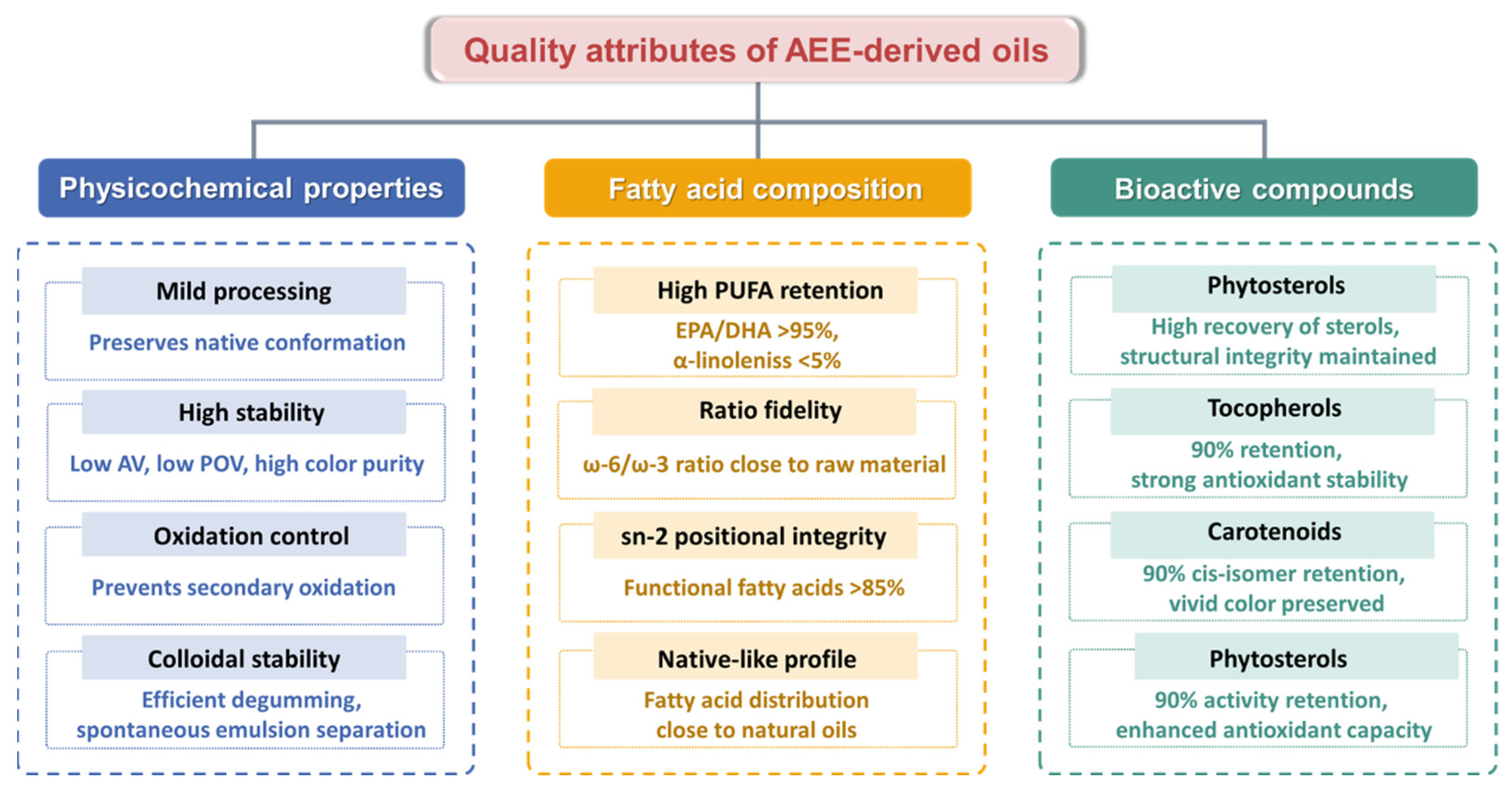

4. High Quality Oils

4.1. Physicochemical Properties

4.2. Fatty Acid Composition

4.3. Bioactive Compounds

4.3.1. Phytosterols

4.3.2. Tocopherol

4.3.3. Carotenoid

4.3.4. Polyphenols

5. Multiphase Proteins

5.1. Aqueous Phase Protein

5.2. Emulsion Phase Proteins

5.3. Solid Phase Proteins

6. Conclusions and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lligadas, G.; Ronda, J.C.; Galià, M.; Cádiz, V. Renewable Polymeric Materials from Vegetable Oils: A Perspective. Mater. Today 2013, 16, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candellone, E.; Aleta, A.; Ferraz de Arruda, H.; Meijaard, E.; Moreno, Y. Characteristics of the Vegetable Oil Debate in Social-Media and Its Implications for Sustainability. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global 2025/26 Vegetable Oil Production Set to Hit Record Levels. Renewable Carbon News, 21 May 2025.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, P.; Wu, F.; He, W.; Mao, L.; Jia, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Jiao, J. Cooking Oil/Fat Consumption and Deaths from Cardiometabolic Diseases and Other Causes: Prospective Analysis of 521,120 Individuals. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025–2034. In OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Shen, M.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Liang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X. Edible Vegetable Oils from Oil Crops: Preparation, Refining, Authenticity Identification and Application. Process Biochem. 2023, 124, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadfar, T.; Sahari, M.A.; Barzegar, M. Bleaching of Olive Oil by Membrane Filtration. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2020, 122, 1900151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, N.-C.; Gao, H.-H.; Qiu, Z.-J.; Deng, Y.-H.; Zhang, Y.-T.; Yang, Z.-C.; Gu, L.-B.; Liu, H.-M.; Zhu, X.-L.; Qin, Z.; et al. Quality and Active Constituents of Safflower Seed Oil: A Comparison of Cold Pressing, Hot Pressing, Soxhlet Extraction and Subcritical Fluid Extraction. LWT 2024, 200, 116184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Ma, X.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Shi, R. Comparison of Key Aroma-Active Compounds between Roasted and Cold-Pressed Sesame Oils. Food Res. Int. 2021, 150, 110794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoro-Alonso, S.; Expósito-Almellón, X.; Martínez-Baena, D.; Martínez-Martí, J.; Rueda-Robles, A.; Pérez-Gálvez, R.; Quirantes-Piné, R.; Lozano-Sánchez, J. Bioactive Enrichment and Sustainable Processing of Vegetable Oils: New Frontiers in Agri-Food Technology. Foods 2025, 14, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahovac, N.; Aleksić, M.; Trajkovska, B.; Marjanović Jeromela, A.; Nakov, G. Extraction and Valorization of Oilseed Cakes for Value-Added Food Components—A Review for a Sustainable Foodstuff Production in a Case Process Approach. Foods 2025, 14, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.S.; Dias, F.F.G.; McDonald, K.A.; de Moura Bell, J.M.L.N. Integrating Functional and Techno-Economic Analyses to Optimize Black Bean Protein Extraction: A Holistic Framework for Process Development. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2025, 10, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Xue, W.; Shen, X.; Hu, W.; Zhao, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, Q. Effects of Microwave-Assisted Enzymatic Treatment on the Quality Characteristics of Sunflower Seed Oil: A Comprehensive Investigation Based on Lipidomics and Volatile Flavor Compound Profiling. Food Chem. 2025, 491, 145217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuhanioglu, A.; Ubeyitogullari, A. Recent Advances in Eco-Friendly Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Fractionation Techniques for Food Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ding, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.-J. Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction: A Green, Environmentally Friendly and Sustainable Oil Extraction Technology. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 144, 104315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassen, A.; Fabre, J.-F.; Lacroux, E.; Cerny, M.; Vaca-Medina, G.; Mouloungui, Z.; Merah, O.; Valentin, R. Aqueous Integrated Process for the Recovery of Oil Bodies or Fatty Acid Emulsions from Sunflower Seeds. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolli, V.; Viscusi, P.; Bonzanini, F.; Conte, A.; Fuso, A.; Larocca, S.; Leni, G.; Caligiani, A. Oil and Protein Extraction from Fruit Seed and Kernel By-Products Using a One Pot Enzymatic-Assisted Mild Extraction. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Yuan, Y.; Xie, T.; Tang, G.; Song, G.; Li, L.; Yuan, T.; Zheng, F.; Gong, J. Ultrasound-Assisted Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction of Gardenia Fruits (Gardenia jasminoides Ellis) Oil: Optimization and Quality Evaluation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 191, 116021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Yong, S.; Yu, Z.; Du, Z. Assembly Complexes of Egg Yolk Low-Density Lipoprotein and Auricularia auricula Polysaccharide Stabilized High Internal Phase Pickering Emulsions: Insights into the Stabilization Mechanism via Fluid-Fluid Interaction between Water and Oil Phases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 141027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshani, R.; Pitcher, M.L.; Yu, J.; Mahajan, C.L.; Kim, S.H.; Sheikhi, A. Plant Cell Wall-Like Soft Materials: Micro- and Nanoengineering, Properties, and Applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 17, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, X.; Durachko, D.M.; Zhang, S.; Cosgrove, D.J. Molecular Insights into the Complex Mechanics of Plant Epidermal Cell Walls. Science 2021, 372, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Structure and Growth of Plant Cell Walls. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, J.; Mikkelsen, D.; Flanagan, B.M.; Dhital, S.; Gaunitz, S.; Henriksson, G.; Lindström, M.E.; Yakubov, G.E.; Gidley, M.J.; Vilaplana, F. Wood Hemicelluloses Exert Distinct Biomechanical Contributions to Cellulose Fibrillar Networks. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Che, R.; Zhu, J.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Fernie, A.R.; Yan, J. Multi-Omics-Driven Advances in the Understanding of Triacylglycerol Biosynthesis in Oil Seeds. Plant J. 2024, 117, 999–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şen, A.; Acevedo-Fani, A.; Dave, A.; Ye, A.; Husny, J.; Singh, H. Plant Oil Bodies and Their Membrane Components: New Natural Materials for Food Applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 256–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Plankensteiner, L.; de Groot, A.; Hennebelle, M.; Sagis, L.M.C.; Nikiforidis, C.V. The Role of Oleosins and Phosphatidylcholines on the Membrane Mechanics of Oleosomes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 678, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- zaaboul, F.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y. Soybean Oil Bodies: A Review on Composition, Properties, Food Applications, and Future Research Aspects. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Fu, R.; Mei, Y.; Wen, X.; Ni, Y.; Boom, R.M.; Nikiforidis, C.V. Combining Colloid Milling and Twin Screw Pressing for Oleosome Extraction. J. Food Eng. 2024, 368, 111908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vovk, H.; Karnpakdee, K.; Ludwig, R.; Nosenko, T. Enzymatic Pretreatment of Plant Cells for Oil Extraction. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2023, 61, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorita, G.D.; Favaro, S.P.; Ambrosi, A.; Di Luccio, M. Aqueous Extraction Processing: An Innovative and Sustainable Approach for Recovery of Unconventional Oils. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 133, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Pignitter, M. Mechanisms of Lipid Oxidation in Water-in-Oil Emulsions and Oxidomics-Guided Discovery of Targeted Protective Approaches. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 2678–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.R.; Stephani, R.; Perrone, Í.T.; de Carvalho, A.F. Plant-Based Proteins: A Review of Factors Modifying the Protein Structure and Affecting Emulsifying Properties. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouseti, O.; Larsen, M.E.; Amin, A.; Bakalis, S.; Petersen, I.L.; Lametsch, R.; Jensen, P.E. Applications of Enzyme Technology to Enhance Transition to Plant Proteins: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, K.; Raak, N.; Gregersen, S.B.; Månsson, L.; Miquel Becker, E. Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of Rapeseed Oil with Minimum Water Addition: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 3013–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelsang-O’Dwyer, M.; Sahin, A.W.; Arendt, E.K.; Zannini, E. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Pulse Proteins as a Tool to Improve Techno-Functional Properties. Foods 2022, 11, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, K.R.; Nema, P.K.; Gupta, R.; Dadhaneeya, H. Optimization and Characterization of Aqueous Enzyme-Assisted Solvent Extraction of Apricot Kernel Oil. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 2989–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ettelaie, R.; Sarkar, A. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Legume Proteins: Lessons on Surface Property Outcomes. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2025, 62, 101259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseke, T.; Opara, U.L.; Fawole, O.A. Effects of Enzymatic Pretreatment of Seeds on the Physicochemical Properties, Bioactive Compounds, and Antioxidant Activity of Pomegranate Seed Oil. Molecules 2021, 26, 4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, F.F.G.; Taha, A.Y.; Leite Nobrega de Moura Bell, J. Effects of Enzymatic Extraction on the Simultaneous Extraction of Oil and Protein from Full-Fat Almond Flour, Insoluble Microstructure, Emulsion Stability and Functionality. Future Foods 2022, 5, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, R.K.; Mondal, I.H.; Dash, K.K.; shaikh, A.M.; Béla, K. Effectiveness of Sustainable Oil Extraction Techniques: A Comprehensive Review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 19, 101546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Ma, Z.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Zheng, H. Optimizing Enzymatic Oil Extraction: Critical Roles of Enzyme Selection, Process Parameters, and Synergistic Effects on Yield and Quality. Food Chem. 2025, 495, 146347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Pérez, L.; Castañeda-Valbuena, D.; Rosales-Quintero, A.; Santiz-Gómez, J.A.; Zimmermann, V.; Virgen-Ortiz, J.J.; Galindo-Ramírez, S.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Tacias-Pascacio, V. Evaluation of Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction for Obtaining Oil from Thevetia peruviana Seeds. Catalysts 2025, 15, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, A.S.; Kashyap, P.; Thakur, M. Effect of Extraction Methods on Functional Properties of Plant Proteins: A Review. eFood 2024, 5, e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piseskul, J.; Suttisansanee, U.; Chupeerach, C.; Khemthong, C.; Thangsiri, S.; Temviriyanukul, P.; Sahasakul, Y.; Santivarangkna, C.; Chamchan, R.; Aursalung, A.; et al. Optimization of Enzyme-Assisted Mechanical Extraction Process of Hodgsonia Heteroclita Oilseeds and Physical, Chemical, and Nutritional Properties of the Oils. Foods 2023, 12, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounika, E.; Smith, D.D.; Edukondalu, D.L.; Raja, D.S. Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction of Rice Bran Oil. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 3149–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Ji, H.; Lin, Q.; Li, X.; Sang, S.; Julian McClements, D.; Chen, L.; Long, J.; Jiao, A.; et al. Physicochemical Stability, Antioxidant Activity, and Antimicrobial Activity of Quercetin-Loaded Zein Nanoparticles Coated with Dextrin-Modified Anionic Polysaccharides. Food Chem. 2023, 415, 135736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Huang, Y.; Islam, S.; Fan, B.; Tong, L.; Wang, F. Influence of the Degree of Hydrolysis on Functional Properties and Antioxidant Activity of Enzymatic Soybean Protein Hydrolysates. Molecules 2022, 27, 6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Tan, Y.; Chang, S.; Li, J.; Maleki, S.; Puppala, N. Peanut Allergen Reduction and Functional Property Improvement by Means of Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Transglutaminase Crosslinking. Food Chem. 2020, 302, 125186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunford, N.T. Enzyme-Aided Oil and Oilseed Processing: Opportunities and Challenges. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 48, 100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Xu, L.; Guan, G.; Wang, F. Ultrasound-Assisted Enzymatic Protein Hydrolysis in Food Processing: Mechanism and Parameters. Foods 2023, 12, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, I.; Kaur, R.; Kumar, A.; Paul, M.; Singh, N. Emerging Protein Sources and Novel Extraction Techniques: A Systematic Review on Sustainable Approaches. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2024, 59, 6797–6820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehrawat, R.; Kaur, B.P.; Nema, P.K.; Tewari, S.; Kumar, L. Microbial Inactivation by High Pressure Processing: Principle, Mechanism and Factors Responsible. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 30, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yao, D.; Xia, S.; Cheong, L.; Tu, M. Recent Progress in Plant-Based Proteins: From Extraction and Modification Methods to Applications in the Food Industry. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Xiao, K.; Li, H.; Qi, Y.; Zou, Z.; Liu, Z. Optimization of Ultrasound Assisted Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction of Oil from Cinnamomum camphora Seeds. LWT 2022, 164, 113689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Z.; Liu, B.; Lai, S.; Wang, Z.; Lv, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, H. Ultrasound-Assisted Enzymatic Extraction of Pinus Pumila Nut Protein: Effects on Yield, Physicochemical and Functional Properties. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Kim, Y. Structural and Functional Enhancement of Okara (Soybean Residue) Proteins Using Microwave- and Ultrasound-Assisted Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Food Biosci. 2025, 71, 107165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Han, L.; Cheng, Y.; Li, G.; Feng, R.; Liu, W.; Sun, Z. Establishment and optimization of the ultrasonic-enzyme assisted aqueous two-phase extraction for obtaining the flavanones from Zhiqiao (Fructus aurantii). Food Ferment. Ind. 2023, 49, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Li, Z.-G.; Gai, Q.-Y.; Li, X.-J.; Wei, F.-Y.; Fu, Y.-J.; Ma, W. Microwave-Assisted Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction of Oil from Pumpkin Seeds and Evaluation of Its Physicochemical Properties, Fatty Acid Compositions and Antioxidant Activities. Food Chem. 2014, 147, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taqi, A.; Farcot, E.; Robinson, J.P.; Binner, E.R. Understanding Microwave Heating in Biomass-Solvent Systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, F.; Du, F.; Wang, A.; Gao, W.; Wang, Q.; Yin, X.; Xie, T. A Novel and Efficient Method for the Immobilization of Thermolysin Using Sodium Chloride Salting-in and Consecutive Microwave Irradiation. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 115, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Cai, Y.; Liu, T.; Long, Z.; Huang, L.; Deng, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, M. Effects of Pretreatments on the Structure and Functional Properties of Okara Protein. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 90, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. Optimization of Microwave Pretreatment Followed by Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction of Tea Seed Oil. Food Sci. 2012, 33, 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Ding, Y.; Rizwan, M.; Ding, Z.; He, Y. Microwave-High Temperature Steaming Assisted Enzymatic Extraction of Soluble Dietary Fiber from Dajiao (Musa paradisiaca L. spp. sapientum (L.), AAB). Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Pino, F.; Leon, M.J.; Millan-Linares, M.C.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S. Antimicrobial Plant-Derived Peptides Obtained by Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Fermentation as Components to Improve Current Food Systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 135, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Oliveira, L.; Martinez-Villaluenga, C.; Frias, J.; Elena Cartea, M.; Francisco, M.; Cristianini, M.; Peñas, E. High Pressure-Assisted Enzymatic Hydrolysis Potentiates the Production of Quinoa Protein Hydrolysates with Antioxidant and ACE-Inhibitory Activities. Food Chem. 2024, 447, 138887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, N.; Shuang, Q.; Bao, X. High-Pressure Processing-Assisted Limited Enzymatic Hydrolysis Improves the Luminosity, Functional Properties, and Digestibility of Sunflower Meal Protein. LWT 2025, 227, 117989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Ban, J.; Li, H.; Chem, J. Lipid extraction from Schizochytrium sp. by enzyme assisted with ultra-high pressure homogenization. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 42, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Huang, Y. Extraction of Antioxidant Peptides and Activity Evaluation of Frog (Rana nigromaculata) Skin by Ultra-high Pressure Assisted Enzyme Hydrolysis. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2025, 46, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbruch, E.; Wise, J.; Levkov, K.; Chemodanov, A.; Israel, Á.; Livney, Y.D.; Golberg, A. Enzymatic Cell Wall Degradation Combined with Pulsed Electric Fields Increases Yields of Water-Soluble-Protein Extraction from the Green Marine Macroalga Ulva sp. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 84, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Sun, Z.; Li, N.; Chen, Q.; Liu, W.; Li, W.; Sun, J. Electrophoretic Coalescence Behavior of Oil Droplets in Oil-in-Water Emulsions Containing SDS under DC Electric Field: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Fuel 2023, 338, 127258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, H. Molecular Dynamics Simulation for the Demulsification of O/W Emulsion under Pulsed Electric Field. Molecules 2022, 27, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbruch, E.; Kashyap, M.; Chemodanov, A.; Levkov, K.; Golberg, A. Continuous Pulsed Electric Field Processing for Intensification of Aqueous Extraction of Protein from Fresh Green Seaweed Ulva sp. Biomass. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 157, 110477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouissi, E.; Faucher, M.; Turgeon, S.L.; Ravallec, R.; Mikhaylin, S. Enhancing the Potential of Brewer’s Spent Grain Utilization in Human Nutrition through Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Protein Extraction. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 104, 104082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prempeh, N.Y.A.; Nunekpeku, X.; Murugesan, A.; Li, H. Ultrasound in the Food Industry: Mechanisms and Applications for Non-Invasive Texture and Quality Analysis. Foods 2025, 14, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandi, B.; Di Massimo, M.; Tedeschi, T.; Rodríguez-Turienzo, L.; Rodríguez, Ó. Ultrasound and Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Proteins from Coffee Green Beans: Effects of Process Variables on the Protein Integrity. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15, 2712–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Sheikh, M.A.; Mir, N.A. A Review on Pulsed Electric Field Modification of Proteins: Effect on the Functional and Structural Properties. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, R.; Krishnan, S.B.; Leong, S.S.J. Pulsed Electric Field Technology for Recovery of Proteins from Waste Plant Resources and Deformed Mushrooms: A Review. Processes 2024, 12, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ji, S.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y.; Tang, W.; Lyu, F. Research Progress and Latest Application of Ultrasonic Treatment on Protein Extraction and Modification. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2024, 59, 4374–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilakarathna, R.C.N.; Siow, L.F.; Tang, T.-K.; Lee, Y.Y. A Review on Application of Ultrasound and Ultrasound Assisted Technology for Seed Oil Extraction. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 1222–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardella, M.; Moscetti, R.; Nallan Chakravartula, S.S.; Bedini, G.; Massantini, R. A Review on High-Power Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Olive Oils: Effect on Oil Yield, Quality, Chemical Composition and Consumer Perception. Foods 2021, 10, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Chaudhary, K.; Amin, S.; Raana, S.; Zahid, M.; Naeem, M.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Aadil, R.M. Recent Advances in the Implementation of Ultrasound Technology for the Extraction of Essential Oils from Terrestrial Plant Materials: A Comprehensive Review. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2024, 107, 106914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, O.V.d.; Freires, S.C.V.; Palheta, H.C.d.O.; Ferreira, P.H.d.M. Impact of Use of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction on the Quality of Brazil Nut Oil (Bertholletia excelsa HBK). Separations 2025, 12, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allay, A.; Benkirane, C.; Moumen, A.B.; Rbah, Y.; Fauconnier, M.-L.; Caid, H.S.; Elamrani, A.; Mansouri, F. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Hemp Seed Oil: Process Optimization for Enhancing Oil Yield and Bioactive Compound Extractability. Int. J. Food Sci. 2025, 2025, 7381308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Poggetto, G.; Di Maro, M.; Gargiulo, L.; Duraccio, D.; Santagata, G.; Gomez d’Ayala, G. Sustainable Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Hemp Seed Oil as Functional Additive into Polybutylene Succinate (PBS) Films for Food Packaging. Polymers 2025, 17, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhadange, Y.A.; Carpenter, J.; Saharan, V.K. A Comprehensive Review on Advanced Extraction Techniques for Retrieving Bioactive Components from Natural Sources. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 31274–31297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Blázquez, S.; Gómez-Mejía, E.; Rosales-Conrado, N.; León-González, M.E. Recent Insights into Eco-Friendly Extraction Techniques for Obtaining Bioactive Compounds from Fruit Seed Oils. Foods 2025, 14, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landim, A.P.M.; Tiburski, J.H.; Mellinger, C.G.; Juliano, P.; Rosenthal, A. Potential Application of High Hydrostatic Pressure on the Production of Hydrolyzed Proteins with Antioxidant and Antihypertensive Properties and Low Allergenicity: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuhanioglu, A.; Alpas, H.; Cekmecelioglu, D. High Hydrostatic Pressure-Assisted Extraction of Lipids from Lipomyces starkeyi Biomass. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 5029–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ates, E.G.; Tonyali Karsli, G.; Alpas, H.; Ozvural, E.B.; Oztop, M.H. Effects of High Hydrostatic Pressure (HHP) on the Extraction and Functional Characteristics of Chickpea Proteins and Saponins. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, A.; Ruiz-Méndez, M.-V.; Sanz, C.; Martínez, M.; Rego, D.; Pérez, A.G. Application of Pulsed Electric Fields to Pilot and Industrial Scale Virgin Olive Oil Extraction: Impact on Organoleptic and Functional Quality. Foods 2022, 11, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Beamonte, R.; Ripalda, M.; Herrero-Continente, T.; Barranquero, C.; Dávalos, A.; López de las Hazas, M.C.; Álvarez-Lanzarote, I.; Sánchez-Gimeno, A.C.; Raso, J.; Arnal, C.; et al. Pulsed Electric Field Increases the Extraction Yield of Extra Virgin Olive Oil without Loss of Its Biological Properties. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1065543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamborrino, A.; Mescia, L.; Taticchi, A.; Berardi, A.; Lamacchia, C.M.; Leone, A.; Servili, M. Continuous Pulsed Electric Field Pilot Plant for Olive Oil Extraction Process. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 82, 103192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, G.; Binello, A.; Aimone, C.; Mantegna, S.; Grillo, G.; Cravotto, G. New Trends in Extraction-Process Intensification: Hybrid and Sequential Green Technologies. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 209, 117906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghraby, Y.R.; El-Shabasy, R.M.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Azzazy, H.M.E.-S. Enzyme Immobilization Technologies and Industrial Applications. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 5184–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekavac, N.; Benković, M.; Jurina, T.; Valinger, D.; Gajdoš Kljusurić, J.; Jurinjak Tušek, A.; Šalić, A. Advancements in Aqueous Two-Phase Systems for Enzyme Extraction, Purification, and Biotransformation. Molecules 2024, 29, 3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R.; Spinelli, R.; Neri, P.; Pini, M.; Barbi, S.; Montorsi, M.; Maistrello, L.; Marseglia, A.; Caligiani, A.; Ferrari, A.M. Life Cycle Assessment of Chemical vs Enzymatic-Assisted Extraction of Proteins from Black Soldier Fly Prepupae for the Preparation of Biomaterials for Potential Agricultural Use. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 14752–14764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravotto, C.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Claux, O.; Abert-Vian, M.; Tabasso, S.; Cravotto, G.; Chemat, F. Towards Substitution of Hexane as Extraction Solvent of Food Products and Ingredients with No Regrets. Foods 2022, 11, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, M.; Cheng, S.; Boonyubol, S.; Cross, J.S. Evaluating Green Solvents for Bio-Oil Extraction: Advancements, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Energies 2023, 16, 5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiri, B.; Cropotova, J.; Kvangarsnes, K.; Gavrilova, O.; Vilu, R. Environmental and Economic Life Cycle Assessment of Enzymatic Hydrolysis-Based Fish Protein and Oil Extraction. Resources 2024, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Hao, J.; Wang, Z.; Liang, D.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, M. Physicochemical Properties, Fatty Acid Compositions, Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Activity and Thermal Behavior of Rice Bran Oil Obtained with Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction. LWT 2021, 149, 111817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prommaban, A.; Kuanchoom, R.; Seepuan, N.; Chaiyana, W. Evaluation of Fatty Acid Compositions, Antioxidant, and Pharmacological Activities of Pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata) Seed Oil from Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction. Plants 2021, 10, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Shen, J.; Wei, J.; Chen, Y. A Critical Review of the Bioactive Ingredients and Biological Functions of camellia oleifera Oil. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 8, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swayne, M.; Perumal, G.; Padmanaban, D.B.; Mariotti, D.; Brabazon, D. Improved Lifetime of a Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) System-Using Laser Induced Surface Oxidation. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 97, 103789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöblom, J.; Mhatre, S.; Simon, S.; Skartlien, R.; Sørland, G. Emulsions in External Electric Fields. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 294, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Martínez, P.; Ortiz-Martínez, V.M.; Sánchez Segado, S.; Salar-García, M.J.; de los Ríos, A.P.; Hernández Fernández, F.J.; Lozano-Blanco, L.J.; Godínez, C. Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Extraction of Fatty Acids from Microalgae Biomass: Recovery of Omega-3 Eicosapentaenoic Acid. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 300, 121842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jiang, N.; Guo, G.; Lu, S.; Li, Z.; Mu, Y.; Xia, X.; Xu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Xiang, X. Perilla Seed Oil: A Review of Health Effects, Encapsulation Strategies and Applications in Food. Foods 2024, 13, 3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, H.; Arai, H.; Kakiuchi, S.; Ito, A.; Sato, K.; Jinno, S.; Takahashi, N.; Masumoto, K.; Yoda, H.; Shimizu, T. Infant Formula with 50% or More of Palmitic Acid Bound to the sn-2 Position of Triacylglycerols Eliminate the Association between Formula-Feeding and the Increase of Fecal Palmitic Acid Levels in Newborns: An Exploratory Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Lehnert, K.; Vetter, W. The High Share of Steryl Esters Is Responsible for the Unusual Sterol Pattern of Black Goji Berries. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 137, 106921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Jing, Y.; Zeng, F.; Xie, J. Phytosterols: Physiological Functions and Potential Application. Foods 2024, 13, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Wu, C.; Lin, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. Integrated Utilization Strategy for Soybean Oil Deodorizer Distillate: Synergically Synthesizing Biodiesel and Recovering Bioactive Compounds by a Combined Enzymatic Process and Molecular Distillation. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 9141–9152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes, S.A.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Dulf, F.V.; Fărcas, A.C.; Vodnar, D.C. Integrated Technology for Cereal Bran Valorization: Perspectives for a Sustainable Industrial Approach. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Lv, M.; Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Chen, D. Analytical Strategies for Tocopherols in Vegetable Oils: Advances in Extraction and Detection. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlton, N.C.; Mastyugin, M.; Török, B.; Török, M. Structural Features of Small Molecule Antioxidants and Strategic Modifications to Improve Potential Bioactivity. Molecules 2023, 28, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tufail, T.; Ain, H.B.U.; Chen, J.; Virk, M.S.; Ahmed, Z.; Ashraf, J.; Shahid, N.U.A.; Xu, B. Contemporary Views of the Extraction, Health Benefits, and Industrial Integration of Rice Bran Oil: A Prominent Ingredient for Holistic Human Health. Foods 2024, 13, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghelichi, S.; Hajfathalian, M.; Yesiltas, B.; Sørensen, A.-D.M.; García-Moreno, P.J.; Jacobsen, C. Oxidation and Oxidative Stability in Emulsions. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 1864–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopov, T.; Nikolova, M.; Dobrev, G.; Taneva, D. Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of Carotenoids from Bulgarian Tomato Peels. Acta Aliment. 2017, 46, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemani, N.; Dehnavi, S.M.; Pazuki, G. Extraction and Separation of Astaxanthin with the Help of Pre-Treatment of Haematococcus Pluvialis Microalgae Biomass Using Aqueous Two-Phase Systems Based on Deep Eutectic Solvents. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narra, F.; Piragine, E.; Benedetti, G.; Ceccanti, C.; Florio, M.; Spezzini, J.; Troisi, F.; Giovannoni, R.; Martelli, A.; Guidi, L. Impact of Thermal Processing on Polyphenols, Carotenoids, Glucosinolates, and Ascorbic Acid in Fruit and Vegetables and Their Cardiovascular Benefits. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Luo, J.; Yang, R.; Li, W. Profiles of Free and Bound Phenolics and Their Antioxidant Capacity in Rice Bean (Vigna umbellata). Foods 2023, 12, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligor, O.; Mocan, A.; Moldovan, C.; Locatelli, M.; Crișan, G.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Enzyme-Assisted Extractions of Polyphenols—A Comprehensive Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poblete, J.; Aranda, M.; Quispe-Fuentes, I. Efficient Conditions of Enzyme-Assisted Extractions and Pressurized Liquids for Recovering Polyphenols with Antioxidant Capacity from Pisco Grape Pomace as a Sustainable Strategy. Molecules 2025, 30, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, L.; Wu, L.; Lin, Q.; Ding, S. Highly Efficient Extraction of Ferulic Acid from Cereal Brans by a New Type A Feruloyl Esterase from Eupenicillium parvum in Combination with Dilute Phosphoric Acid Pretreatment. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 190, 1561–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amić, A.; Mastil’ák Cagardová, D. A DFT Study of the Antioxidant Potency of α-Tocopherol and Its Derivatives: PMHC, Trolox, and α-CEHC. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 403, 124796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Xu, Y.; Chang, M.; Tang, L.; Lu, M.; Liu, R.; Jin, Q.; Wang, X. Antioxidant Interaction of α-Tocopherol, γ-Oryzanol and Phytosterol in Rice Bran Oil. Food Chem. 2021, 343, 128431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesano, D.; Rocchetti, G.; Cossignani, L.; Senizza, B.; Pollini, L.; Lucini, L.; Blasi, F. Untargeted Metabolomics to Evaluate the Stability of Extra-Virgin Olive Oil with Added Lycium barbarum Carotenoids during Storage. Foods 2019, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wu, B.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, B.; Wang, Q. Improving Enzyme Accessibility in the Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction Process by Microwave-Induced Porous Cell Walls to Increase Oil Body and Protein Yields. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liang, X.; Wei, M.; Zhao, W.; He, B.; Lu, Q.; Huo, Q.; Ma, C. Optimization of Glutamine Peptide Production from Soybean Meal and Analysis of Molecular Weight Distribution of Hydrolysates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 7483–7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-H.; Wang, X.-Y.; Yang, X.-Q.; Li, L. Formation of Soluble Aggregates from Insoluble Commercial Soy Protein Isolate by Means of Ultrasonic Treatment and Their Gelling Properties. J. Food Eng. 2009, 92, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Gao, L.; Geng, Q.; Li, T.; He, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Dai, T. Effects of Moderate Enzymatic Hydrolysis on Structure and Functional Properties of Pea Protein. Foods 2022, 11, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, A.; Liu, H.; Hu, H.; Wang, Q.; Adhikari, B.; Jiao, B.; Pignitter, M. Effect of Hydrothermal Cooking Combined with High-Pressure Homogenization and Enzymatic Hydrolysis on the Solubility and Stability of Peanut Protein at Low pH. Foods 2022, 11, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Yu, G.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, T.; Zhu, J. Effect of Enzymatic Hydrolysis on the Physicochemical and Emulsification Properties of Rice Bran Albumin and Globulin Fractions. LWT 2022, 156, 113005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner-Williams, W.M.; Stevens, B.R.; Moughan, P.J. Are Intact Peptides Absorbed from the Healthy Gut in the Adult Human? Nutr. Res. Rev. 2014, 27, 308–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Du, W.; Huang, H.; Wan, L.; Shang, C.; Mao, X.; Kong, X. Research Progress on the Mechanism of Action of Food-Derived ACE-Inhibitory Peptides. Life 2025, 15, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qi, B.; Sui, X.; Jiang, L. Recovery of High Value-added Protein from Enzyme-assisted Aqueous Extraction (EAE) of Soybeans by Dead-end Ultrafiltration. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, X.; Lian, Z.; Miao, L.; Qi, B.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L. An Innovative Two-Step Enzyme-Assisted Aqueous Extraction for the Production of Reduced Bitterness Soybean Protein Hydrolysates with High Nutritional Value. LWT 2020, 134, 110151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, S.; Sun, N.; Cui, W.; Cheng, L.; Ren, K.; Wang, M.; Tong, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, H. Effects of Sucrase Enzymatic Hydrolysis Combined with Maillard Reaction on Soy Protein Hydrolysates: Bitterness and Functional Properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Dai, F.-J.; Chen, C.-Y.; Fan, S.-L.; Zheng, J.-H.; Chau, C.-F.; Lin, Y.-S.; Chen, C.-S. Effects of Molecular Weight Fraction on Antioxidation Capacity of Rice Protein Hydrolysates. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasrichan, S.; Janssen, A.E.M.; Boom, R. Contribution of Sequential Pretreatments and Enzyme-Assisted Extraction to Rice Bran Protein Yield Improvement. J. Cereal Sci. 2024, 118, 103970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Kriisa, M.; Föste, M.; Kütt, M.-L.; Zhou, Y.; Laaksonen, O.; Yang, B. Impact of Enzymatic Pre-Treatment on Composition of Nutrients and Phytochemicals of Canola (Brassica napus) Oil Press Residues. Food Chem. 2022, 387, 132911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetzer, A.; Herfellner, T.; Stäbler, A.; Menner, M.; Eisner, P. Influence of Process Conditions during Aqueous Protein Extraction upon Yield from Pre-Pressed and Cold-Pressed Rapeseed Press Cake. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommi, K.; Hakala, T.K.; Holopainen, U.; Nordlund, E.; Poutanen, K.; Lantto, R. Effect of Enzyme-Aided Cell Wall Disintegration on Protein Extractability from Intact and Dehulled Rapeseed (Brassica rapa L. and Brassica napus L.) Press Cakes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 7989–7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Gasmalla, M.A.A.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, R.; Aboagarib, E.A.A. Characterization and Demusification of Cream Emulsion from Aqueous Extraction of Peanut. J. Food Eng. 2016, 185, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yang, C.; Liu, K.; Zhu, T.; Duan, X.; Xu, Y. Demulsification of Emulsion Using Heptanoic Acid during Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction and the Characterization of Peanut Oil and Proteins Extracted. Foods 2023, 12, 3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, X.; Lu, X.; Wei, S.; Sun, Q.; Jin, L.; Song, G.; You, J.; Li, F. Characterization of Peanut Protein Hydrolysate and Structural Identification of Umami-Enhancing Peptides. Molecules 2022, 27, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Feng, Z.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Feng, M.; Chen, Q.; Kong, B.; Liu, H. Synergistic Effects of Ultrasound and pH-Shifting on the Solubility and Emulsification Properties of Peanut Protein. Foods 2025, 14, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chutinara, C.; Sagis, L.M.C.; Landman, J. Interfacial Rheological Properties of Pepsin-Hydrolyzed Lentil Protein Isolate at Oil-Water Interfaces. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 155, 110201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, N.; Chen, F.; Zhang, J.; Sun, X.; Xu, L.; Fang, F. Review on the Release Mechanism and Debittering Technology of Bitter Peptides from Protein Hydrolysates. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 5153–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Ma, R.; Tang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. Structural Properties and Antioxidant Activities of Soybean Protein Hydrolysates Produced by Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus cell envelope proteinase. Food Chem. 2023, 410, 135392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ung, T.T.; Sah, D.K.; Park, S.Y.; Lakshmanan, V.-K.; Jung, Y.D. Piperine Attenuates Lithocholic Acid-Stimulated Interleukin-8 by Suppressing Src/EGFR and Reactive Oxygen Species in Human Colorectal Cancer Cells. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsaard, W.; Kate-Ngam, S.; Onsaard, E. Physicochemical and Antioxidant Properties of Rice Bran Protein Hydrolysates Obtained from Different Proteases. Food Meas. 2023, 17, 2374–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münch, K.; Takeuchi, M.; Tuinier, R.; Stoyanov, S.; Schroën, K.; Friedrich, H.; Berton-Carabin, C. Mixed Interfaces Comprising Pea Proteins and Phosphatidylcholine: A Route to Modulate Lipid Oxidation in Emulsions? Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 153, 109962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, F.; Pradilla, D.; Cruz, J.C.; Alvarez, O. Emerging Emulsifiers: Conceptual Basis for the Identification and Rational Design of Peptides with Surface Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yu, Y. Improving the Stability of Water-in-Oil Emulsions with Medium Internal Phase by the Introduction of Gelatin. Foods 2023, 12, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wali, A.; Ma, H.; Shahnawaz, M.; Hayat, K.; Xiaong, J.; Jing, L. Impact of Power Ultrasound on Antihypertensive Activity, Functional Properties, and Thermal Stability of Rapeseed Protein Hydrolysates. J. Chem. 2017, 2017, 4373859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Xiang, F.; Liu, Y.; Yan, J.; Wang, J. Fabrication and Encapsulation of Soy Peptide Nanoparticles Using Ultrasound Followed by Spray Drying. Foods 2024, 13, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Dou, J.; Zhu, B.; Ning, Y.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Qi, B.; Jiang, L. Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Heat-Induced Soybean Protein Hydrolysate Gels Subjected to Ultrasound-Assisted pH Pretreatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 95, 106403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Wei, S.; Qi, K.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Secondary Structure of Proteins on Oil Release in Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction of Rapeseed Oil as Affected Hydrolysis State. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés García, A.; Castillo Sanchis, J.; Cenitagoya Alonso, N.; Beltrán Sanahuja, A. Sustainable Valorization of Horchata de Chufa By-Products Through Optimized Ultrasound-Enzymatic Extraction: Recovery of Oil and Dietary Fiber. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 8670–8685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichare, S.A.; Morya, S. Exploring Waste Utilization Potential: Nutritional, Functional and Medicinal Properties of Oilseed Cakes. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1441029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process Parameter | Impact on Oil Extraction Yield | Impact on Protein Quality | Impact on Energy Consumption & Economics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Type | Combined enzymes (cellulase + pectinase) yield > 90%, significantly higher than single enzyme (~70%); proteases increase free oil yield by 5–15% via demulsification. | Proteases lead to a degree of hydrolysis (DH) of 5–15%; excessive hydrolysis (DH > 15%) increases bitter peptides and reduces the emulsifying activity index by over 30%. | Combined enzymes cost 20–50% more than single enzymes, but overall economics can be optimized via higher yield and reduced downstream demulsification steps. | [15,32,33,34,35] |

| Enzyme Concentration | Oil yield increases significantly within 1.0–2.5%range (40–85%); plateaus with minimal gains (<5% increase) above 3.0%. | Concentrations > 2.5% cause over-hydrolysis, reducing emulsifying stability by 20–40% with negligible solubility improvement (<5%). | Enzymes account for 30–60% of production cost; each 0.5% concentration increase raises cost by 12–18% | [12,36,37,38] |

| Reaction Time | Oil yield peaks (85–92%) within 60–90 min; extending to 120 min increases yield <3%, but may raise oil peroxide value by 0.5–1.0 meq/kg | Time > 120 min reduces protein emulsifying capacity by 25% with no significant solubility gain, increasing microbial risk. | Each 30 min extension increases energy use by 15–25%; optimal timing saves 20–35% in total energy. | [29,36,39,40] |

| Reaction Temperature | Maximum oil yield (85–90%) at 45–55 °C; >60 °C causes rapid enzyme deactivation, reducing yield by 20–30%; <40 °C reduces reaction rate by 50%. | Temperatures > 65 °C induce protein denaturation, reducing Nitrogen Solubility Index (NSI) by 15–25%; <40 °C lowers protein yield by 30–40%. | Temperature control consumes 40–60% of total energy; each 5 °C increase raises energy use by 12–15%; optimal range maximizes energy efficiency. | [41,42,43,44] |

| Raw Material | Type & Molecular Weight | Key Functional Property | Application Potential | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean | AEE skim proteins & hydrolysates; peak < 10 kDa; UF 3–5 kDa | Higher solubility; fewer antinutritional factors | Nutrition supplements; acidic-pH beverages | [134,135,136] |

| Rice bran | Soluble proteins/hydrolysates; UF < 3, 3–5, 5–10 kDa; ≤3–5 kDa most active | Antioxidant and ACE-inhibitory; emulsification improved | Functional foods and beverages | [137,138] |

| Rapeseed/Canola | AEE skim proteins/hydrolysates; low-MW enriched (peak < 10 kDa); UF 3–5 kDa | High solubility; strong emulsifying/interfacial film-forming | Clean-label emulsifiers; plant-based beverages/creams | [139,140,141] |

| Peanut | Skim and demulsified interfacial proteins; low-MW enriched (peak < 10 kDa); UF 3–5 kDa | Superior interfacial/emulsifying performance; umami-enhancing peptides identified | Plant-based beverages/creams; clean-label emulsifiers | [142,143,144] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, Z.; Chen, J.; Guo, X.; Chen, F.; Guo, X.; Wang, Q.; Jiao, B. Mechanism and Potential of Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction for Constructing Green Production System for Lipids and Proteins. Foods 2025, 14, 3981. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14233981

Jiang Z, Chen J, Guo X, Chen F, Guo X, Wang Q, Jiao B. Mechanism and Potential of Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction for Constructing Green Production System for Lipids and Proteins. Foods. 2025; 14(23):3981. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14233981

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Zefang, Jiaqi Chen, Xin Guo, Fusheng Chen, Xingfeng Guo, Qiang Wang, and Bo Jiao. 2025. "Mechanism and Potential of Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction for Constructing Green Production System for Lipids and Proteins" Foods 14, no. 23: 3981. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14233981

APA StyleJiang, Z., Chen, J., Guo, X., Chen, F., Guo, X., Wang, Q., & Jiao, B. (2025). Mechanism and Potential of Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction for Constructing Green Production System for Lipids and Proteins. Foods, 14(23), 3981. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14233981