Advances in Food Processing Techniques for Allergenicity Reduction and Allergen Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Origin of Food Allergens

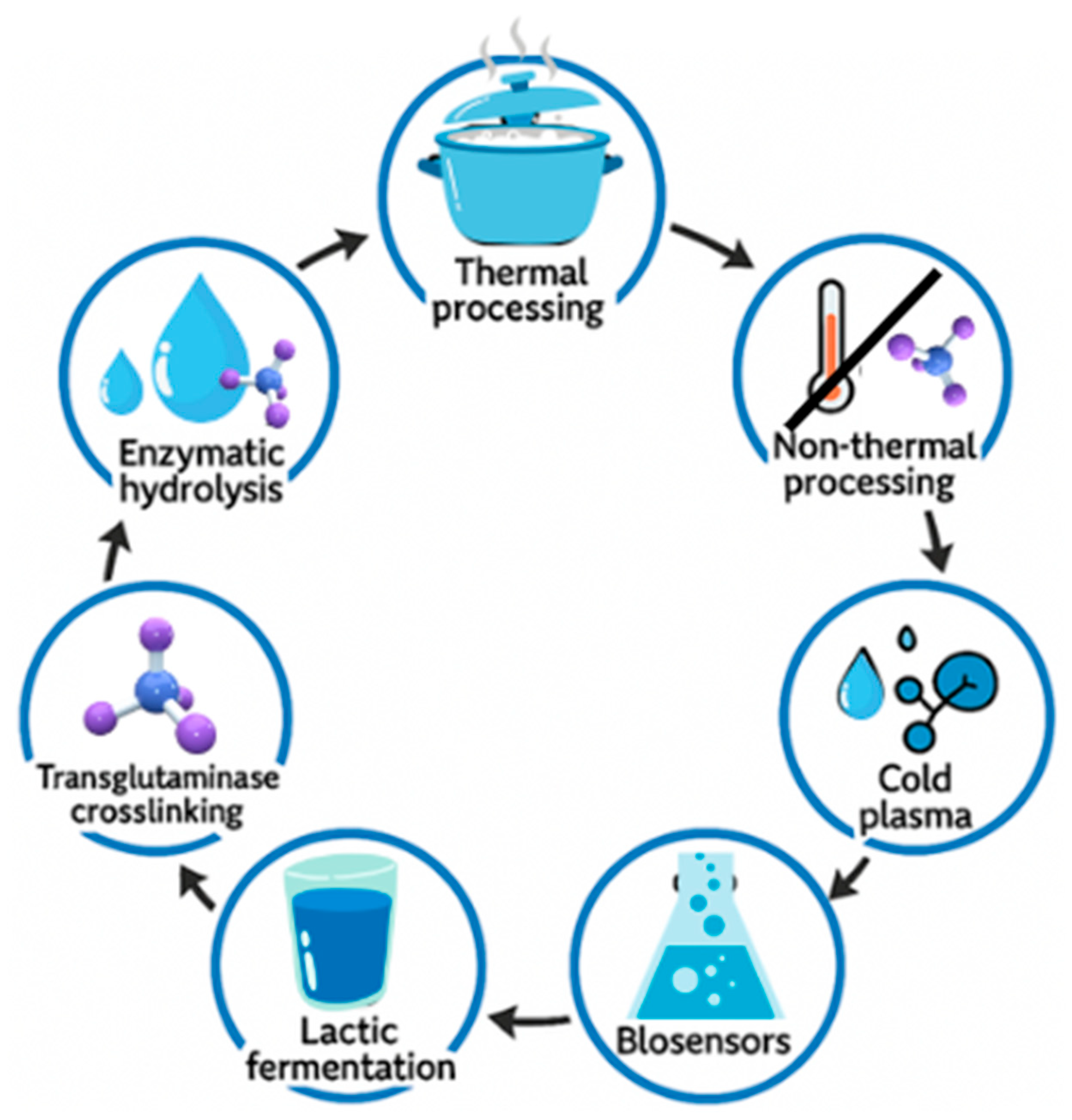

3. Allergen-Reducing Food Processing

3.1. Thermal Food Processing

3.2. Acid Treatment Method

3.3. Microwave Treatment

3.4. Food Fermentation

3.5. High-Pressure Processing (HPP)

3.6. Ultrasound, Pulsed Electric Field (PEF)

3.7. UV Radiation

3.8. Enzymatic Modification

3.9. Cold Plasma

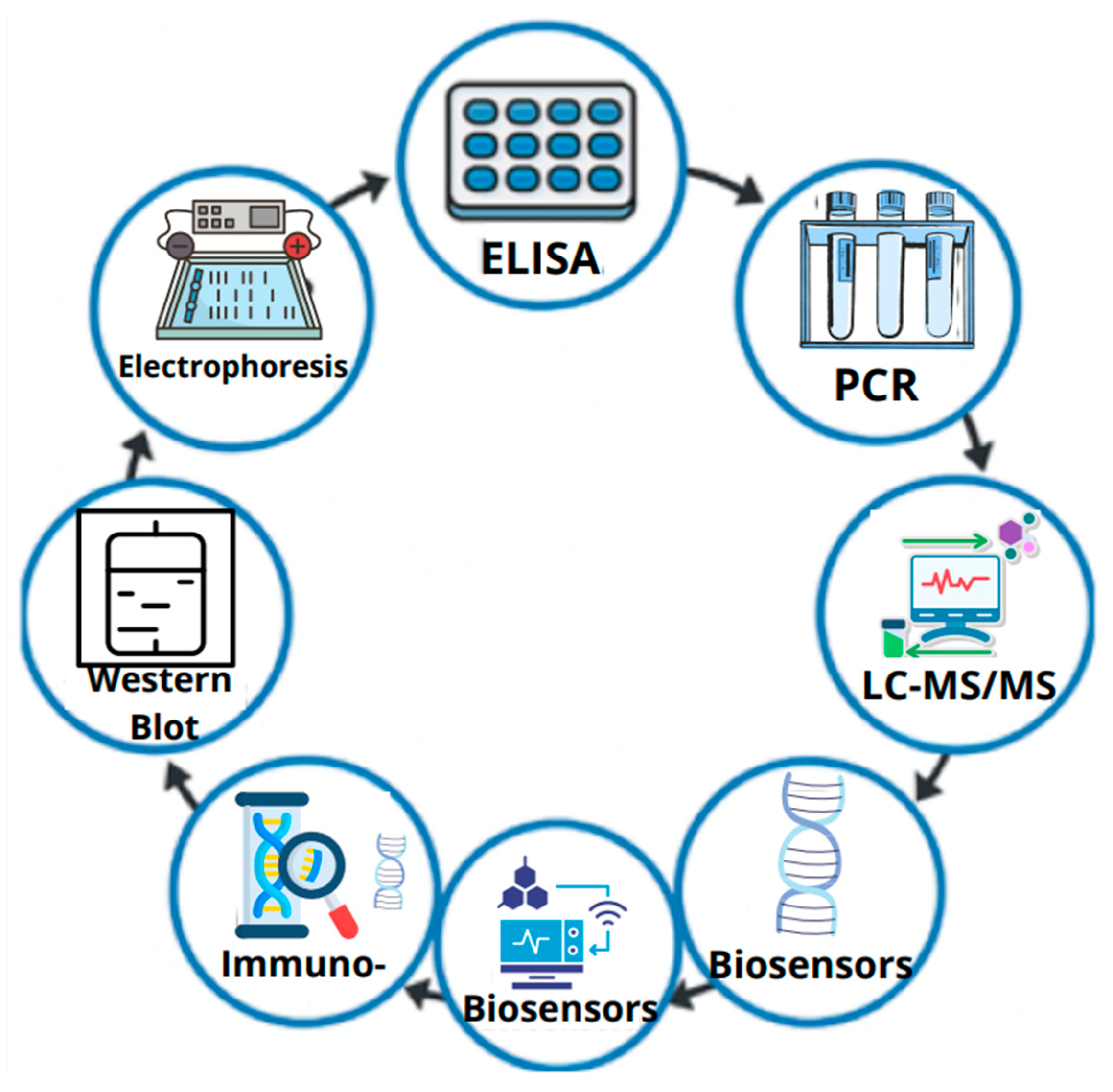

4. Methods for the Detection of Allergenic Proteins

4.1. Immunoblotting

4.1.1. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.1.2. SDS-PAGE: Separation of Proteins by Electrophoresis in a Polyacrylamide Gel

4.1.3. Western Blot (WB) Analysis

4.2. Mass Spectrometry-Based Techniques

4.2.1. Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

4.2.2. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

4.3. Biological Biosensors

4.4. DNA-Based Methods for Understanding Proteins Encoded in DNA

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Method

5. Technological and Economic Aspects of Reducing Protein Allergenicity

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D-E | Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis |

| AF | Allergenicity Factor |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| EU | European Union |

| FA | Food Allergy |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| HPP | High-Pressure Processing |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| Ka | Constant Association Rate |

| LAB | Lactic Acid Bacteria |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| NHIS | National Health Interview Survey |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PEF | Ultrasound, Pulsed Electric Field |

| RAST | Radio Allergo Sorbent Test |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| WB | Western Blot |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Kostova, P.; Papochieva, V.; Shahid, M.; Petrova, G. Food allergy as one of the faces of primary immunodeficiency. Explor. Asthma Allergy 2024, 2, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Chen, H.; Gao, J. Oral exposure to nano- and microplastics: Potential effects in food allergies? Allergy Med. 2024, 1, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, H.; Li, Z.; Lin, H. Dietary AGEs and food allergy: Insights into the mechanisms of AGEs-induced food allergy and mitigation strategies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 7853–7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, Y.S.; Williams, L.L. The Rising Incidence of Food Allergies and Infant Food Allergies. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 16, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.M.; Sehgal, S.; Sicherer, S.H.; Gupta, R.S. Epidemiology and the Growing Epidemic of Food Allergy in Children and Adults Across the Globe. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2024, 24, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Crowe, S.E. Food Allergies. In Clinical Nutrition in Gastrointestinal Disease; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.C.K.; Trogen, B.; Brady, K.; Ford, L.S.; Wang, J. The Natural History and Risk Factors for the Development of Food Allergies in Children and Adults. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2024, 24, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaneghah, A.M.; Nematollahi, A.; AbdiMoghadam, Z.; Davoudi, M.; Mostashari, P.; Marszałek, K.; Aliyeva, A.; Javanmardi, F. Research progress in the application of emerging technology for reducing food allergens as a global health concern: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 9789–9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Warren, C.M.; Brewer, A.; Soffer, G.; Gupta, R.S. Racial, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Differences in Food Allergies in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2318162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manti, S.; Galletta, F.; Bencivenga, C.L.; Bettini, I.; Klain, A.; D’Addio, E.; Mori, F.; Licari, A.; del Giudice, M.M.; Indolfi, C. Food Allergy Risk: A Comprehensive Review of Maternal Interventions for Food Allergy Prevention. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Wang, J.; Raghavan, V. Gut microbiome modulation by probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics: A novel strategy in food allergy prevention and treatment. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 5984–6000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, D.M.; Chan, E.S.; Venter, C.; Spergel, J.M.; Abrams, E.M.; Stukus, D.; Groetch, M.; Shaker, M.; Greenhawt, M.; Durham, K.A.; et al. A consensus approach to the primary prevention of food allergy through nutrition. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Food Allergens. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/pl/safe2eat/food-allergens (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Spolidoro, G.C.I.; Nyassi, S.; Lisik, D.; Ioannidou, A.; Ali, M.M.; Amera, Y.T.; Rovner, G.; Khaleva, E.; Venter, C.; van Ree, R.; et al. Food allergy outside the eight big foods in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2024, 14, e12338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caimmi, D.; Clark, E.; Giannì, G.; Caffarelli, C. IgE-Mediated Food Allergy. In Textbook of Pediatric Allergy; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Chittipolu, A.; Yerrakula, G. Technology to Produce Hypoallergenic Food with High Quality. In Food Allergies: Processing Technologies for Allergenicity Reduction; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; p. 276. [Google Scholar]

- Soós, G.; Lugasi, A. Consumer attitude research regarding food hypersensitivity. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 36, 100918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźniar, J.; Kozubek, P.; Gomułka, K. Differences in the Course, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Food Allergies Depending on Age—Comparison of Children and Adults. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas, Y.; Broekaert, I.; Domellöf, M.; Indrio, F.; Lapillonne, A.; Pienar, C.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Shamir, R.; Szajewska, H.; Thapar, N.; et al. An ESPGHAN position paper on the diagnosis, management, and prevention of cow’s milk allergy. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 78, 386–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, A.A.; Priyesh, P.V.; Odugbemi, A.A. The Magnitude and Impact of Food Allergens and the Potential of AI-Based Non-Destructive Testing Methods in Their Detection and Quantification. Foods 2024, 13, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Weger, W.W.; Sprikkelman, A.B.; Herpertz, C.E.; van Der Meulen, G.N.; Vonk, J.M.; Koppelman, G.H.; Kamps, A.W. Comparison of Double-Blind and Open Food Challenges for the Diagnosis of Food Allergy in Childhood: The ALDORADO Study. Allergy 2025, 80, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S.; Warren, C.M.; Smith, B.M.; Jiang, J.; Blumenstock, J.A.; Davis, M.M.; Schleimer, R.P.; Nadeau, K.C. Prevalence and Severity of Food Allergies Among US Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e185630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.G.; Kosowan, L.; Soller, L.; Chan, E.S.; Nankissoor, N.N.; Phung, R.R.; Abrams, E.M. Prevalence of physician-reported food allergy in Canadian children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.A.; Silva, A.F.M.; Ribeiro, Â.C.; Silva, A.O.; Vieira, F.A.; Segundo, G.R. Adult food allergy prevalence: Reducing questionnaire bias. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 171, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.A.; Clausen, M.; Knulst, A.C.; Ballmer-Weber, B.K.; Fernandez-Rivas, M.; Barreales, L.; Bieli, C.; Dubakiene, R.; Fernandez-Perez, C.; Jedrzejczak-Czechowicz, M.; et al. Prevalence of food sensitization and food allergy in children across Europe. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 2736–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, I.; Almulhem, N.; Santos, A.F. Feast for thought: A comprehensive review of food allergy 2021–2023. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 153, 576–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolidoro, G.C.; Amera, Y.T.; Ali, M.M.; Nyassi, S.; Lisik, D.; Ioannidou, A.; Rovner, G.; Khaleva, E.; Venter, C.; van Ree, R.; et al. Frequency of food allergy in Europe: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2023, 78, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knyziak-Mędrzycka, I.; Majsiak, E.; Gromek, W.; Kozłowska, D.; Swadźba, J.; Bierła, J.B.; Kurzawa, R.; Cukrowska, B. The Sensitization Profile for Selected Food Allergens in Polish Children Assessed with the Use of a Precision Allergy Molecular Diagnostic Technique. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahid, U.; Ashraf, W.; Ali, K.; Niazi, S.; Iqbal, M.W.; Nisha, S.; Mustafa, S.; Naseem, T.; Nasir, M.A.; Shoaib, M.; et al. Emerging Nonthermal Technologies for Allergen Reduction in Foods: A Systematic Review. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2025, 2025, 3503385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, C.; Sanchiz, Á.; Linacero, R. Nut Allergenicity: Effect of food processing. Allergies 2021, 1, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaghi, M.; Maleki, S.J. Mitigating Food Protein Allergenicity with Biopolymers, Bioactive Compounds, and Enzymes. Allergies 2024, 4, 234–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Hinds, L.M.; Soro, A.B.; Hu, Z.; Sun, D.-W.; Tiwari, B.K. Non-Thermal Processing Technologies for Allergen Control in Alternative Protein Sources for Food Industry Applications. Food Eng. Rev. 2024, 16, 595–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, C.; Cheng, H.; Sanchiz, A.; Ballesteros, I.; Easson, M.; Grimm, C.C.; Dieguez, M.C.; Linacero, R.; Burbano, C.; Maleki, S.J. Influence of enzymatic hydrolysis on the allergenic reactivity of processed cashew and pistachio. Food Chem. 2018, 241, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.N.; Rodrigues, R.M.; Madalena, D.A.; Vicente, A. Tackling food allergens—The role of food processing on proteins’ allergenicity. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 106, 317–351. [Google Scholar]

- Masson, P.; Lushchekina, S. Conformational Stability and Denaturation Processes of Proteins Investigated by Electrophoresis under Extreme Conditions. Molecules 2022, 27, 6861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogahawaththa, D.; Vasiljevic, T. Denaturation of selected bioactive whey proteins during pasteurization and their ability to modulate milk immunogenicity. J. Dairy Res. 2020, 87, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawanda, S.K.; Ramaswamy, H.S. Yellow Mustard Protein a Immunoreactivity Reduction Through Seed Germination, Lactic Acid Fermentation, and Cooking. Foods 2024, 13, 3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahe, M.; Käser, T. Immune System. Dis. Swine 2025, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Freeland, D.M.H.; Nadeau, K.C. Food allergy: Immune mechanisms, diagnosis and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerezsi, A.D.; Wang, W.; Jacquet, N.; Blecker, C. Advances on physical treatments for soy allergens reduction—A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 122, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, H.; Yamamura, A.; Kimijima, T.; Ishizaki, S.; Ochiai, Y. Elimination of the major allergen tropomyosin from shrimp muscle by boiling treatment. Fish. Sci. 2020, 86, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipozenčić, J.; Wolf, R. Life-threatening severe allergic reactions: Urticaria, angioedema, and anaphylaxis. Clin. Dermatol. 2005, 23, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luccioli, S.; Seabol, L. Anaphylaxis in children: Latest insights. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2025, 46, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and the Council. Off. J. Eur. Union 2011, L 304/18, 18–63. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, T.; Rustgi, S. Peanut Genotypes with Reduced Content of Immunogenic Proteins by Breeding, Biotechnology, and Management: Prospects and Challenges. Plants 2025, 14, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evrard, B.; Cosme, J.; Raveau, M.; Junda, M.; Michaud, E.; Bonnet, B. Utility of the Basophil Activation Test Using Gly m 4, Gly m 5 and Gly m 6 Molecular Allergens for Characterizing Anaphylactic Reactions to Soy. Front. Allergy 2022, 3, 908435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppelman, S.; Wensing, M.; Ertmann, M.; Knulst, A.; Knol, E. Relevance of Ara h1, Ara h2 and Ara h3 in peanut-allergic patients, as determined by immunoglobulin E Western blotting, basophil–histamine release and intracutaneous testing: Ara h2 is the most important peanut allergen. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2004, 34, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousou, C.; Kostin, E.; Christodoulou, E.; Theodorou, T.; Pavlou, Z.; Pitsios, C. Pollen Food Allergy Syndrome in Southern European Adults: Patterns and Insights. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Deng, S.; Guan, K.; Xiang, L. Pollen food allergy syndrome in China: Current knowledge and future research needs. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2025, 186, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Figueroa, R.H.; López-Malo, A.; Mani-López, E. Sourdough Fermentation and Gluten Reduction: A Biotechnological Approach for Gluten-Related Disorders. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, J.M.; Buckow, R.; Vasiljevic, T.; Donkor, O.P. Effect of simulated digestion on antigenicity of banana prawn (Fenneropenaeus merguiensis) after high pressure processing at different temperatures. Food Control 2019, 104, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasekan, A.; Cao, H.J.; Maleki, S.; Nayak, B. Shrimp tropomyosin retains antibody reactivity after exposure to acidic conditions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 3623–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Platts-Mills, T.A. Meat allergy and allergens. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 100, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdougall, J.D.; O Thomas, K.; I Iweala, O. The Meat of the Matter: Understanding and Managing Alpha-Gal Syndrome. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2022, 11, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakonechna, A.; van Bergen, A.; Anantharachagan, A.; Arnold, D.; Johnston, N.; Nadeau, K.; Rutkowski, K.; Sindher, S.B.; Sriaroon, P.; Thomas, I.; et al. Fish and shellfish allergy: Presentation and management differences in the UK and US—Analysis of 945 patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Glob. 2024, 3, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remington, B.C.; Westerhout, J.; Meima, M.Y.; Blom, W.M.; Kruizinga, A.G.; Wheeler, M.W.; Taylor, S.L.; Houben, G.F.; Baumert, J.L. Updated population minimal eliciting dose distributions for use in risk assessment of 14 priority food allergens. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 139, 111259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ul Ain, N.; Anjum, S.A. Food allergens: Identification, cross-reactivity, and advances in detection strategies. Food Nutr. Insights 2024, 2, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lisiecka, M.Z. Meat allergy: Specific reactions to chicken, beef, pork, and alternative protein sources. Asia Pac. Allergy 2025, 15, e5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhout, J.; Baumert, J.L.; Blom, W.M.; Allen, K.J.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; Crevel, R.W.; Dubois, A.E.; Fernández-Rivas, M.; Greenhawt, M.J.; Hourihane, J.O.; et al. Deriving individual threshold doses from clinical food challenge data for population risk assessment of food allergens. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 1290–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, G.F.; Baumert, J.L.; Blom, W.M.; Kruizinga, A.G.; Meima, M.Y.; Remington, B.C.; Wheeler, M.W.; Westerhout, J.; Taylor, S.L. Full range of population Eliciting Dose values for 14 priority allergenic foods and recommendations for use in risk characterization. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 146, 111831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popping, B. FAO/WHO Publish New Recommended Food Allergen Threshold Levels. FOCOS. Available online: https://www.focos-food.com/fao-who-publish-new-recommended-food-allergen-threshold-levels/ (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- FAO/WHO. Recommended Food Allergen Thresholds. Open Knowledge Repository. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240042391 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Gunal-Koroglu, D.; Karabulut, G.; Ozkan, G.; Yılmaz, H.; Gültekin-Subaşı, B.; Capanoglu, E. Allergenicity of alter-native proteins: Reduction mechanisms and processing strategies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 7522–7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, E.; Li, Q.; Zhu, D.; Chen, G.; Wu, L. Characterization of physicochemical and immunogenic properties of allergenic proteins altered by food processing: A review. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 1135–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, P.M.; Cassin, A.M.; Durban, R.; Upton, J.E. Effects of food processing on allergenicity. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2025, 25, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Raghavan, V.; Wang, J. Traditional and Emerging Physical Processing Technologies: Applications and Challenges in Allergen Control of Animal and Plant Proteins. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokri, S.; Jarpa-Parra, M. Editorial: Advancements in protein modification for enhanced digestibility. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1603394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarhan, Ö.; Venerando, A.; Falsafi, R.; Rostamabadi, H.; Rashidinejad, A.; Capanoglu, E.; Tomas, M.; Karaca, A.C.; Lee, C.-C.; Pourjafar, H.; et al. Minimization of Protein Allergenicity in Food Products Through Conventional and Novel Processes: A Comprehensive Review on Mechanisms, Detection, and Applications. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Qu, X.; Xie, C.; Xu, T.; Song, F.; Lv, L. Impact of Heat Treatment on the Allergenic Potential of Penaeus chinensis TM: A Comprehensive Analysis of Structural Changes, Molecular Dynamics, Digestibility, Allergenicity and Gut Microbiota Alterations. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 15321–15332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.H.; Huang, Y.; Burton-Freeman, B.M.; Edirisinghe, I. Chemical Changes of Bioactive Phytochemicals during Thermal Processing. Food Sci. 2016, 9, 137734480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, F.; Tabbassum, M.; Kesharwani, P. Investigation on Secondary Structure Alterations of Protein Drugs as an Indicator of Their Biological Activity Upon Thermal Exposure. Protein J. 2019, 38, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcune, I.; Elorza, E.; de Luzuriaga, A.R.; Huegun, A.; Rekondo, A.; Grande, H.-J. Analysis of the Effect of Network Structure and Disulfide Concentration on Vitrimer Properties. Polymers 2023, 15, 4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satish, L.; Millan, S.; Das, S.; Jena, S.; Sahoo, H. Thermal Aggregation of Bovine Serum Albumin in Conventional Buffers: An Insight into Molecular Level Interactions. J. Solut. Chem. 2017, 46, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodkorb, A.; Croguennec, T.; Bouhallab, S.; Kehoe, J.J. Heat-Induced Denaturation, Aggregation and Gelation of Whey Proteins. In Advanced Dairy Chemistry: Volume 1B: Proteins: Applied Aspects; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschke, A. Aspects of food processing and its effect on allergen structure. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009, 53, 959–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Κωστή, Ρ.Ι.; Τρίγκα, Μ.; Τσαμπούρη, Σ.; Πρίφτης, Κ.Ν. Food allergen selective thermal processing regimens may change oral tolerance in infancy. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2015, 41, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Duodu, S.O.; Santra, S.; Lalsangi, S.B.; Naduviledathu, A.; Bharati, R.; Das, S.; Banerjee, R. An inclusive insight on dietary resistant protein and protein hydrolysates: Structural intricacy, bioactivity and benefits on human health. Food Bioacromol. 2025, 2, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wei, M.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Ning, C.; Hu, F. Effects of Heat Treatment on Structure and Processing Characteristics of Donkey Milk Whey Protein. J. Food Biochem. 2024, 2024, 5598462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Cherayil, B.J.; Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, L.; Zhu, Y. Food Processing to Eliminate Food Allergens and the Development of Hypoallergenic Foods. In Food Allergy: From Molecular Mechanisms to Control Strategies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavaro, S.L.; Di Stasio, L.; Mamone, G.; De Angelis, E.; Nocerino, R.; Canani, R.B.; Logrieco, A.F.; Montemurro, N.; Monaci, L. Effect of thermal/pressure processing and simulated human digestion on the immunoreactivity of extractable peanut allergens. Food Res. Int. 2018, 109, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomaa, N.A.; Boye, J.I. Impact of thermal processing time and cookie size on the detection of casein, egg, gluten and soy allergens in food. Food Res. Int. 2013, 52, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Meng, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z. Study on the technological process of hydrolyzed whey protein. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2011, 34, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, H.; Wu, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, Z. The effect of processing methods on the immunologic of the major allergens of Penes prawns. Aquac. J. 2011, 35, 948–953. [Google Scholar]

- Lechevalier, V.; Guérin-Dubiard, C.; Anton, M.; Beaumal, V.; David Briand, E.; Gillard, A.; Le Gouar, Y.; Musikaphun, N.; Pasco, M.; Dupont, D. Effect of dry heat treatment of egg white powder on its functional, nutritional and allergenic properties. J. Food Eng. 2017, 195, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, M.L.; Soumya, C.; Prabhasankar, P. Use of dry-moist heat effects to improve the functionality, immunogenicity of whole wheat flour and its application in bread making. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 69, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.; Moura, M.B.M.V.; Costa, J.; Mafra, I. Immunoreactivity of Lupine and Soybean Allergens in Foods as Affected by Thermal Processing. Foods 2020, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, A.; Ramaswamy, H.S. ELISA Based Immunoreactivity Reduction of Soy Allergens through Thermal Processing. Processes 2022, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobajas, A.P.; Agulló-García, A.; Cubero, J.L.; Colás, C.; Civera, A.; Condón, S.; Sánchez, L.; Pérez, M.D. Effect of thermal and ultrasound treatments on denaturation and allergenic potential of Pru p 3 protein from peach. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.F.; He, S.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Advances in epitope mapping technologies for food protein allergens: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 107, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namiki, M. Chemistry of Maillard reactions: Recent studies on the browning reaction mechanism and the development of antioxidants and mutagens. Adv. Food Res. 1988, 32, 115–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, M.N.; Ray, C.A. Control of Maillard Reactions in Foods: Strategies and Chemical Mechanisms. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 4537–4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparini, A.; Buhler, S.; Faccini, A.; Sforza, S.; Tedeschi, T. Thermally-Induced Lactosylation of Whey Proteins: Identification and Synthesis of Lactosylated β-lactoglobulin Epitope. Molecules 2020, 25, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, M.; Wellner, A.; Gadermaier, G.; Ilchmann, A.; Briza, P.; Krause, M.; Nagai, R.; Burgdorf, S.; Scheurer, S.; Vieths, S.; et al. Ovalbumin Modified with Pyrraline, a Maillard Reaction Product, shows Enhanced T-cell Immunogenicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 7919–7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B. Effect of Thermal Processing on Food Allergenicity: Mechanisms, Application, Influence Factor, and Future Perspective. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 20225–20240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Rao, H.; Zhang, K.; Tao, S.; Xue, W. Effects of different thermal processing methods on the structure and allergenicity of peanut allergen Ara h 1. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golkar, A.; Milani, J.M.; Vasiljevic, T. Altering allergenicity of cow’s milk by food processing for applications in infant formula. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas, B.; Novak, N. Effects of daily food processing on allergenicity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymkiewicz, A.; Jędrychowski, L.; Wagner, A.N.E.T.A. The effect of thermal treatment and enzymatic hydrolysis on the allergenicity of pea proteins. Food Sci. Technol. Qual. 2007, 3, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Sung, D.; Park, S.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Shon, D.; Ahn, K.; Han, Y. Effect of acid treatment on allergenicity of peanut and egg. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 2116–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.; Mattison, C.P.; Grimm, C.C.; Reed, S. Simple methods to reduce major allergens Ara h 1 and Ana o 1/2 in peanut and cashew extracts. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 5, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.-Y.; Mattison, C.P.; Reed, S.; Wasserman, R.L.; Desormeaux, W.A. Treatment with oleic acid reduces IgE binding to peanut and cashew allergens. Food Chem. 2015, 180, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Fang, L.; Gu, R.; Lu, J.; Li, G. Effect of acid and in vitro digestion on conformation and IgE-binding capacity of major oyster allergen Cra g 1 (tropomyosin). Allergol. Immunopathol. 2020, 48, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, F.E.B.; Rodrigues, S.; Fonteles, T.V. Non-Thermal Technologies in Food Fermentation: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Industrial Perspectives for Sustainable Development. Processes 2025, 13, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Li, R.; Chen, C.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Man, C.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Y. Combined processing technologies: Promising approaches for reducing Allergenicity of food allergens. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Chen, C.; Liu, M.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Shi, J.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Y. A comprehensive review of effects of ultrasound pretreatment on processing technologies for food allergens: Allergenicity, nutritional value, and technofunctional properties and safety assessment. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röder, M.; Wiacek, C.; Lankamp, F.; Kreyer, J.; Weber, W.; Ueberham, E. Improved Sensitivity of Allergen Detection by Immunoaffinity LC-MS/MS Using Ovalbumin as a Case Study. Foods 2021, 10, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Tian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, M.; Guo, J.; Song, Y.; et al. Electromagnetic wave-based technology for ready-to-eat foods preservation: A review of applications, challenges and prospects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 4703–4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Huang, H.; Huang, S.; Yang, M.; Wu, J.; Ci, Z.; He, Y.; Wu, Z.; Han, L.; Zhang, D. Insight into the incredible effects of microwave heating: Driving changes in the structure, properties and functions of macromolecular nutrients in novel food. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 941527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, M.; Szczepańska-Stolarczyk, J.; Woźniak, Ł.; Jasińska, U.T.; Trych, U.; Cywińska-Antonik, M.; Kosiński, J.; Kaniewska, B.; Marszałek, K. Evaluating the Impact of Microwave vs. Conventional Pasteurization on NFC Apple–Peach and Apple–Chokeberry Juices: A Comparative Analysis at Industrial Scale. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.; Irawan, F.; Han, H.E.; Jun, S.; Cho, D.H.; Chung, H.J. Effect of Thermal Treatment on Nutritional and Physicochemical Properties of Sweet Pumpkin Flour and its Impact on Resistant Starch and Sensory Quality of Muffins and Noodles. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zou, Y.; Yan, B.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Fan, D. Microwave treatment on structure and digestibility characteristics of Spirulina platensis protein. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Hoz, A.; Díaz-Ortiz, Á.; Moreno, A. Microwaves in organic synthesis. Thermal and non-thermal microwave effects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczynska, J.; Łącka, A.; Szemraj, J.; Lukamowicz, J.; Zegota, H. The effect of microwave treatment on the im-munoreactivity of gliadin and wheat flour. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2003, 217, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Banik, B.K. Microwave-Assisted Enzymatic. In Microwaves in Chemistry Applications: Fundamentals, Methods and Future Trends; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 245–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanga, S.K.; Singh, A.; Raghavan, V. Review of conventional and novel food processing methods on food allergens. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2077–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap-Singh, A.; Shabbir, M.A.; Ahmed, W. Effect of Microwaves on Food Proteins. In Microwave Processing of Foods; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Shi, J.; Vanga, S.K.; Raghavan, V. Effect of microwave processing on the nutritional properties and allergenic potential of kiwifruit. Food Chem. 2023, 401, 134189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Tu, Z.C.; Wen, P.W.; Hu, Y.M.; Wang, H. Investigating the Mechanism of Microwave-Assisted Enzymolysis Synergized with Magnetic Bead Adsorption for Reducing Ovalbumin Allergenicity through Biomass Spectrometry Analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 14011–14021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazikalović, I.; Mijalković, J.; Šekuljica, N.; Tanasković, S.J.; Vuković, A.Đ.; Mojović, L.; Knežević-Jugović, Z. Synergistic Effect of Enzyme Hydrolysis and Microwave Reactor Pretreatment as an Efficient Procedure for Gluten Content Reduction. Foods 2021, 10, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mecherfi, K.E.; Curet, S.; Lupi, R.; Larré, C.; Rouaud, O.; Choiset, Y.; Rabesona, H.; Haertlé, T. Combined microwave processing and enzymatic proteolysis of bovine whey proteins: The impact on bovine β-lactoglobulin allergenicity. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.A.; Rodrigues, S. Cold plasma technology for sustainable food production: Meeting the United Nations sustainable development goals. Sustain. Food Technol. 2025, 3, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, A.; Villanueva, M.; Caballero, P.A.; Lazaridou, A.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Ronda, F. Flours from microwave-treated buckwheat grains improve the physical properties and nutritional quality of gluten-free bread. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 149, 109644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Marin, S.; Ayala-Larrea, D.; Cardador-Martínez, A.; Tellez-Perez, C.; Resendiz-Vazquez, J.A.; Alonzo-Macias, M. Non-Thermal Food Processing for Plant Protein Allergenicity Reduction: A Systematic Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chobot, M.; Kozłowska, M.; Ignaczak, A.; Kowalska, H. Drying and roasting processes for plant-based snacks. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 149, 104553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielak, M.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Kraujutienė, I. Microwave heating in food industry and households. Post. Techn. Przetw. Spoż. 2022, 1, 152–167. Available online: https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-5a3ca383-80bd-4872-840f-7526abf3c253 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Yang, X.; Ren, X.; Ma, H. Effect of Microwave Pretreatment on the Antioxidant Activity and Stability of Enzymatic Products from Milk Protein. Foods 2022, 11, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap-Singh, A.; Ahmed, W. Effect of Microwaves on Food Quality Parameters. In Microwave Processing of Foods; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.L.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y.M.; Wang, X.M.; Chen, H.Q.; Tu, Z.C. Allergenicity reduction of ovalbumin by mi-crowave-assisted enzymolysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 15363–15374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.C.; Paramithiotis, S.; Thekkangil, A.; Nethravathy, V.; Rai, A.K.; Martin, J.G.P. Food Fermentation in Human History. In Trending Topics on Fermented Foods; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.-H.; Mu, D.-D.; Guo, L.; Wu, X.-F.; Chen, X.-S.; Li, X.-J. From flavor to function: A review of fermented fruit drinks, their microbial profiles and health benefits. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 115095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, S.S.; Park, H.Y.; Sim, E.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Choi, H.S. Microbial fermentation in food: Functional properties and nutritional enhancement. Fermentation 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, N. Fermentation’s role in plant-based foods. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Erol, Z.; Rugji, J.; Taşçı, F.; Kahraman, H.A.; Toppi, V.; Musa, L.; Di Giacinto, G.; Bahmid, N.A.; Mehdizadeh, M.; et al. Fermentation in the food industry. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2023, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, L. Lactic acid bacteria as mucosal delivery vehicles: A realistic therapeutic option. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 5691–5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofvendahl, K.; Hahn–Hägerdal, B. Factors affecting the fermentative lactic acid production from renewable resources1. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2000, 26, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnu, C.; Bachinger, T.; Seenayya, G.; Reddy, G. Direct conversion of starch to L (+) lactic acid. Bioprocess. Eng. 2000, 23, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, G.T.; Cao, N.J.; Du, J.; Gong, C.S. Production of Multifunctional Organic Acids from Renewable Resources. In Recent Progress in Bioconversion of Lignocellulosics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 65, pp. 243–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Rahim, M.H.; Hazrin-Chong, N.H.; Harith, H.H.; Wan, W.A.A.Q.I.; Sukor, R. Roles of fermented plant-, dairy-and meat-based foods in the modulation of allergic responses. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, J.; Song, Y.S.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; de Mejia, E.G.; Vidal-Valverde, C. Fermented soyabean products as hypoallergenic food. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2008, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mecherfi, K.-E.; Todorov, S.D.; de Albuquerque, M.A.C.; Denery-Papini, S.; Lupi, R.; Haertlé, T.; Franco, B.D.G.d.M.; Larré, C. Allergenicity of Fermented Foods: Emphasis on Seeds Protein-Based Products. Foods 2020, 9, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, R.; Harada, Y.; Yano, E.; Zaima, N.; Moriyama, T. Soybean Allergen Detection for Hypoallergenicity Val-idation of Natto—A Fermented Soybean Food. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Fu, G.; Dong, B.; Yang, Y.; Wan, Y.; Xie, M. Effects of fermentation with Bacillus natto on the allergenicity of peanut. LWT 2021, 141, 110862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mecherfi, K.E.; Lupi, R.; Cherkaoui, M.; Albuquerque, M.A.; Todorov, S.D.; Tranquet, O.; Klingebiel, C.; Rogniaux, H.; Denery-Papini, S.; Onno, B.; et al. Fermentation of gluten by Lactococcus lactis LLGKC18 reduces its antigenicity and allergenicity. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 14, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, K.; Lidzba, N.; Ueberham, E.; Eisner, P.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U. Fermentation of Lupin Protein Hydrolysates—Effects on Their Functional Properties, Sensory Profile and the Allergenic Potential of the Major Lupin Allergen Lup an 1. Foods 2021, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.S.; Frías, J.; Martinez-Villaluenga, C.; Vidal-Valdeverde, C.; de Mejia, E.G. Immunoreactivity reduction of soybean meal by fermentation. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.W.; Hsu, C.P.; Wang, C.Y. Healthy expectations of high hydrostatic pressure treatment in food processing industry. J. Food Drug Anal. 2020, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, V.R.; Popović, V.; Bissonnette, S.; Ros, I.; Mats, L.; Duizer, L.; Warriner, K.; Koutchma, T. Quality changes in cold pressed juices after processing by high hydrostatic pressure, ultraviolet-c light and thermal treatment at commercial regimes. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 64, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehrawat, R.; Kaur, B.P.; Nema, P.K.; Tewari, S.; Kumar, L. Microbial inactivation by high pressure processing: Principle, mechanism and factors responsible. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 30, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Shahbaz, H.; Javed, F.; Park, J. Applications of HPP for Extraction of Bioactive Compounds. In Advances in Food Applications for High Pressure Processing Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lamela, C.; Franco, I.; Falqué, E. Impact of High-Pressure Processing on Antioxidant Activity during Storage of Fruits and Fruit Products: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goraya, R.K.; Singla, M.; Kaura, R.; Singh, C.B.; Singh, A. Exploring the impact of high pressure processing on the characteristics of processed fruit and vegetable products: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 3856–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghmare, R. High pressure processing of fruit beverages: A recent trend. Food Humanit. 2024, 2, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, P.; Ganguly, A.; Nanda, S.; Ghanty, S. Food Allergies and Processing of Soy Products. In Food Allergies; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braspaiboon, S.; Laokuldilok, T. High hydrostatic pressure: Influences on allergenicity, bioactivities, and structural and functional properties of proteins from diverse food sources. Foods 2024, 13, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.K.; Sit, N. Fruit and vegetable processing using traditional and novel methods: A review. Future Postharvest Food 2025, 2, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavilla, M.; Puértolas, E.; Orcajo, J. HPP Impact to Reduce Allergenicity of Foods. In Present and Future of High Pressure Processing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Hsu, C.; Yang, B.B.; Wang, C. Potential Utility of High-Pressure Processing to Address the Risk of Food Allergen Concerns. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavilla, M.; Orcajo, J.; Díaz-Perales, A.; Gamboa, P. Examining the effect of High Pressure Processing on the allergenic potential of the major allergen in peach (Pru p 3). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 38, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Liu, J.; Ren, S.; Zhu, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, B. Ultrasound-assisted treatment to reduce food allergenicity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Chua, J.V.; Le, Q.A.; Trujillo, F.J.; Oh, M.-H.; Campbell, D.E.; Mehr, S.; Lee, N.A. Optimizing attenuation of IgE-reactivity to β-Lactoglobulin by high pressure processing. Foods 2021, 10, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klinmalai, P.; Kamonpatana, P.; Thongpech, A.; Sodsai, J.; Promhuad, K.; Srisa, A.; Laorenza, Y.; Kovitvadhi, A.; Areerat, S.; Seubsai, A.; et al. Alternative proteins in pet food: Trends in plant, aquatic, insect, and cell-based sources. Foods 2025, 14, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kumar, N.; Kuang, H.; Song, J.; Li, Y. Changes of digestive stability and potential allergenicity of high hydrostatic pressure-treated ovalbumin during in vitro digestion. Food Chemis. 2025, 473, 142962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landim, A.P.M.; Tiburski, J.H.; Mellinger, C.G.; Juliano, P.; Rosenthal, A. High pressure processing for hydrolyzed proteins with antioxidant and antihypertensive properties. Foods 2023, 12, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouryieh, H. Impact of High Pressure Processing on the Safety and Quality of Food Products: A Review. Recent. Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 2024, 16, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, J.; Aleanizy, F.S.; Alqahtani, F.Y. Nanotechnology Approaches for Mitigating Biologic Immunogenicity: A Literature Review. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, A.; Fatma, N.; Faraz, A.; Pervez, M.; Khan, M.A.; Husain, A. Advancements in the conservation of the conformational epitope of membrane protein immunogens. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1538871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Tang, B.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Ma, R.; Peng, Y.; Wu, X.; Che, L.; He, N.; Ling, X.; et al. Effect of High Hydrostatic Pressure (HHP) Processing on Immunoreactivity and Spatial Structure of Peanut Major Allergen Ara h 1. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2020, 13, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landim, A.P.; Matsubara, N.K.; da Silva-Santos, J.E.; Mellinger-Silva, C.; Rosenthal, A. High-pressure processing for improving bioactivity and reducing antigenicity of whey protein hydrolysates. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2022, 28, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Ojalvo, D.; Pérez-Rodríguez, L.; Pablos-Tanarro, A.; López-Fandiño, R.; Molina, E. Pepsin treatment of whey proteins under high pressure produces hypoallergenic hydrolysates. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 43, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathania, N.; Dubey, P.K. Influence of ultrasonication on nutritional aspects of fruit juice blends. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 60, vvae086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Ye, H.; Cao, Q.; Jia, Y.; Chen, Y.; Bo, C.; Li, B.; Chu, J. Recent advances of high-intensity ultrasound on protein structure and quality: Allergenicity, physicochemical properties, functionality assessment and future perspective. Food Chem. 2025, 495, 146518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pi, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, F.; Zhang, B. Combined ultrasound with other technologies for reducing food aller-genicity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 16095–16111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prempeh, N.Y.A.; Nunekpeku, X.; Murugesan, A.; Li, H. Ultrasound in food industry: Non-invasive texture and quality analysis. Foods 2025, 14, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, A.S.; Suryawanshi, D.; Kumar, M.; Waghmare, R. Ultrasonic treatment: A cohort review on bioactive compounds, allergens and physico-chemical properties of food. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, P.Y.; Yu, R.; Yeo, S.E.; Choi, Y.S.; Hwangbo, S.; Yong, H.I. Ultrasound application to animal-based food for microbial safety. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2025, 45, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Ren, S.; Ye, H.; Cao, J.; Chu, J.; Cao, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, B. A review of wheat allergy: Allergens characteristic, the impact of processing on allergenicity and future perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 164, 105244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Cui, F.-J.; Ullah, M.W.; Qayum, A.; Khalifa, I.; Bacha, S.A.S.; Ying, Z.-Z.; Khan, I.; Zeb, U.; Alarfaj, A.A.; et al. Bioactive curdlan and sodium alginate films for shelf life extension. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlan, M.; Rosarina, D.; Ratna Suminar, H.F.; Diatama Pohan, Y.; Hidayatullah, I.M.; Narawangsa, D.R.; Putri, D.N.; Sari, E.; Perdani, M.S.; Wibowo, Y.G.; et al. Microwave–Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Coupled with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent Enables High-Yield, Low-Solvent Recovery of Curcumin from Curcuma longa L. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, F.Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, R.R.; Hu, X.S.; Chen, F. Combined high pressure and thermal treatments on shrimp allergen tropomyosin. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2015, 29, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Wan, Y.; Fu, G.; Li, X.; Cheng, J. Food irradiation for hypoallergenic food production. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 62, 6698–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Bu, G.; Xi, G. Heat treatment effects on β-conglycinin antigenicity and structure. Food Chem. 2021, 346, 128962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, K.S.; Tiwari, B.K.; O’Donnell, C.P. Ultrasound technology effects on food and nutrition. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 84, 207–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; Ramísio, P.J.; Van Hulle, S.W.; Puga, H. Ultrasound-assisted advanced oxidation removal of contaminants of emerging concern: A review on present status and an outlook to future possibilities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 496, 139164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-X.; Lin, H.; Cao, L.-M.; Jameel, K. High intensity ultrasound reduces shrimp allergenicity. J. Zhejiang Univ. B 2006, 7, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilles, C.; Newgreen, D.F.; Sato, H.; Thompson, E.W. Matrix Metalloproteases and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. In Rise and Fall of Epithelial Phenotype; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 297–315. [Google Scholar]

- López-Expósito, I.E. Processing technologies and food allergenicity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 1902–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moirangthem, R.; Gamage, M.N.; Rokita, S.E. Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and DNA conformation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 5341–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzza, P.; Honisch, C.; Hussain, R.; Siligardi, G. Free Radicals and ROS Induce Protein Denaturation by UV Photostability Assay. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhendi, A.S. Pulsed light treatment effects on enzymes and protein allergens. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 2853–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.W.; Mwakatage, N.R.; Goodrich-Schneider, R.; Krishnamurthy, K.; Rababah, T.M. Mitigation of peanut allergens by pulsed UV light. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 2728–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, F.; Pizarro-Oteíza, S.; Kasahara, I.; Labbé, M.; Estay, C.; Tarnok, M.E.; Aguilar, L.; Ibáñez, R.A. Pulsed UV light effects on cow’s milk proteins. J. Food Process. Eng. 2024, 47, e14629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, K.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Lou, Q.; Xu, D.; Yang, W. Studying on the IgG binding capacity and conformation of tropomyosin in Ovalipes punctatus meat irradiated with electron beam. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2020, 168, 108525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, A.; Mei, K.; Lv, M.; Lu, J.; Lou, Q.; Yang, W. Electron beam irradiation effects on shrimp tropomyosin. Food Chem. 2018, 264, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemmireddy, V.; Adhikari, A.; Moreira, J. Effect of ultraviolet light treatment on microbiological safety and quality of fresh produce: An overview. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 871243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, F.; Pizarro-Oteíza, S.; Kasahara, I.; Labbé, M. Effect of ultraviolet light-emitting diode processing on fruit and vegetable-based liquid foods: A review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1020886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager, T.L.; Cockrell, A.E.; Du Plessis, S.S. Ultraviolet Light Induced Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species. In Ultraviolet Light in Human Health, Diseases and Environment; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 996, pp. 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khora, S.S. Marine Fish-Derived Proteins as Antioxidants. In Marine Antioxidants; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhong, H.; Cheng, J.-H. Non-thermal processing effects on seafood allergens. Molecules 2022, 27, 5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azubuike-Osu, S.O.; Ekezie, F.-G.C.; Ibegbunam, W.E.; Udenigwe, C.C. Allergic Effects of Bioactive Peptides. In Bioactive Peptides; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 363–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Liu, M.; Li, X.; Guo, L.; Man, C.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Y. Enzymatic hydrolysis and allergenicity. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, T.; Vasiljevic, T.; Ramchandran, L. Processing effects on protein allergenicity. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 49, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Mi, R.; Li, Y.; Wen, Z.; Li, S. Protease hydrolysis of Antheraea pernyi pupa protein. J. Insect Sci. 2021, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.; Huang, G. Enzymatic crosslinking and food allergenicity: A comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 5856–5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, S.; Chen, Y.; Song, J.; Jin, J.; Gao, R. Effects of enzymolysis on allergenicity and digestibility of food allergens. Food Sci. Anim. Prod. 2024, 2, 9240082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Luo, X.; Sun, J.; Yang, M.; Zheng, Y. Cow milk allergenicity after enzymatic hydrolysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.; Shi, J.; Zhao, Q.; Jiang, Y. Effect of enzymatic hydrolysis pretreatment on beta-lactoglobulin amyloid fibril allergenicity: In vivo studies and in vitro digestion product. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 145701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.; Teixeira, C.; Carriço-Sá, B.; Dias, C.; Costa, J.; Mafra, I. Enzymatic hydrolysis as a strategy to reduce the allergenicity in sesame (Sesamum indicum) proteins. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 106, 104284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimareva, L.V.; Sokolova, E.N.; Serba, E.M.; Borshcheva, Y.A.; Kurbatova, E.I.; Krivova, A.Y. Reduced allergenicity of plant foods via enzymatic hydrolysis. Orient. J. Chem. 2017, 33, 2009–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparre, N.; Rosell, C.M.; Boukid, F. Enzymatic hydrolysis of plant proteins. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 18, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Gao, L.; Geng, Q.; Li, T.; He, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Dai, T. Moderate enzymatic hydrolysis of pea protein. Foods 2022, 11, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunde, O.O.; Owolabi, I.O.; Fadairo, O.S.; Ghosal, A.; Coker, O.J.; Soladoye, O.P.; Aluko, R.E.; Bandara, N. Enzymatic Modification of Plant Proteins for Improved Functional and Bioactive Properties. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 16, 1216–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadorshabi, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Shamloo, E.; Mahmoudzadeh, M. Marine Algae-Derived Bioactives: A Sustainable Resource for the Food and Agriculture Industries. Food Front. 2025, 6, 2514–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintieri, L.; Monaci, L.; Baruzzi, F.; Giuffrida, M.G.; de Candia, S.; Caputo, L. Reduction of whey protein anti-genicity. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 1910–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcinai, L.; Bonomini, M.G.; Leni, G.; Faccini, A.; Puxeddu, I.; Giannini, D.; Petrelli, F.; Prandi, B.; Sforza, S.; Tedeschi, T. Effectiveness of enzymatic hydrolysis for reducing the allergenic potential of legume by-products. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanillas, B.; Pedrosa, M.M.; Rodríguez, J.; Muzquiz, M.; Maleki, S.J.; Cuadrado, C.; Burbano, C.; Crespo, J.F. Enzymatic hydrolysis reduces allergenicity of roasted peanut protein. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2011, 157, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, S.; Li, Y. Two-step enzymatic modification reduces milk protein immunoreactivity. Food Chem. 2017, 237, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Liu, M.; Chen, C.; Huang, Z.; Liu, S.; Man, C.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X. Effects of ultrasound pretreatment on the structure, IgE binding capacity, functional properties and bioactivity of whey protein hydrolysates via multispectroscopy and peptidomics revealed. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 110, 107025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedé, S.; Martínez-Blanco, M.; López-Fandiño, R.; Molina, E. IgE-Binding and Immunostimulating Properties of Enzymatic Crosslinked Milk Proteins as Influenced by Food Matrix and Digestibility. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cywińska-Antonik, M.; Chen, Z.; Groele, B.; Marszałek, K. Application of Emerging Techniques in Reduction of the Sugar Content of Fruit Juice: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Foods 2023, 12, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P. Enzymes in Food Processing: A Condensed Overview on Strategies for Better Biocatalysts. Enzym. Res. 2010, 2010, 862537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allai, F.M.; Azad, Z.R.A.A.; Mir, N.A.; Gul, K. Advances in nonthermal processing for shelf life and safety. Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucar, Y.; Ceylan, Z.; Durmus, M.; Tomar, O.; Cetinkaya, T. Cold plasma in food industry and emerging tech. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melios, S.; Stramarkou, M.; Grasso, S. Consumer perception of nonthermal food processing. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 223, 117688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelakshmi, V.P.; Vendan, S.E.; Negi, P.S. Cold plasma for pesticide decontamination in spinach. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 220, 113322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.-C.; Lin, C.-S.; Lee, Y.-C.; Kang, C.; Kuo, C.-H.; Hsu, T.; Tsai, Y.-H. High-hydrostatic pressure extends shelf life of miso-marinated escolar. Food Control 2025, 169, 111031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaddu, S.; Sonkar, S.; Seth, D.; Dwivedi, M.; Pradhan, R.C.; Goksen, G.; Sarangi, P.K.; Jambrak, A.R. Cold plasma effects on food hydration and nutrition. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtaza, B.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Saleemi, M.K.; Nawaz, M.Y.; Li, M.; Xu, Y. Cold plasma: Cold plasma mitigates mycotoxins and enhances food value. Food Chem. 2024, 445, 138378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrads, H.; Schmidt, M. Plasma generation and plasma sources. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2000, 9, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peratt, A.L. Physics of the Plasma Universe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Varilla, C.; Marcone, M.; Annor, G.A. Cold plasma for food safety: A review. Foods 2020, 9, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwabor, O.F.; Onyeaka, H.; Miri, T.; Obileke, K.; Anumudu, C.; Hart, A. Cold plasma for microbiological safety. Food Eng. Rev. 2022, 14, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.C.; Lin, W.T.; Hsieh, K.C.; Cheng, K.C.; Wu, J.S.B.; Ting, Y. Cold plasma mitigates peanut allergen Ara h 1. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 3017–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, K.-C.; Ting, Y. Atmospheric cold plasma reduces Ara h 1 antigenicity. Food Chem. 2024, 441, 138115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataratnam, H.; Cahill, O.; Sarangapani, C.; Cullen, P.J.; Barry-Ryan, C. Cold plasma processing impacts peanut allergens. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W. Cold plasma reduces coconut globulin IgE affinity. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Raghavan, V.; Wang, J. Cold plasma improves egg white protein digestibility. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 105014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Wang, F.; Cheng, J.H.; Wong, S.H.D. Cold plasma + glycation alters shrimp tropomyosin IgE binding. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 15796–15808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Gao, Z.; Liu, D.; Chitrakar, B. Allergens from wheat and wheat products: A comprehensive review on allergy mechanisms and modifications. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luparelli, A.; De Angelis, E.; Pilolli, R.; Lambertini, F.; Suman, M.; Monaci, L. Mass Spectrometry-Based Method for Multiple Allergens Control: Application to Bakery Goods. Foods 2025, 14, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, V.V.; Pratima, C. Modalities of protein denaturation and nature of denaturants. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2021, 69, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatelain, P.G.; Van Wyk, J.J.; Copeland, K.C.; Blethen, S.L.; Underwood, L.E. Serum proteases and somatomedin-C. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1983, 56, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveday, S.M. Protein digestion and food processing. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2023, 36, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, S.; Zou, H.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, R. Microwave heating effects on gluten proteins. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2139–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, C.; Sanchiz, A.; Vicente, F.; Ballesteros, I.; Linacero, R. Pressure processing alters tree nut proteins. Molecules 2020, 25, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, R.; Li, W.; Rui, X. Lactic acid fermentation and soy protein immunoreactivity. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 4291–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Pang, L.; Li, S.; Su, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Y. Effects of physical processing on food protein allergenicity: A focus on differences between animal and alternative proteins. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhao, Q.; Bu, G.; Shi, S.; Zhu, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure combined with enzymatic hydrolysis on the allergenicity, structural properties, and antigenic epitopes of soybean glycinin. LWT 2025, 236, 118682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifa Lestari, T.F.; Irkham, I.; Pratomo, U.; Gaffar, S.; Zakiyyah, S.N.; Rahmawati, I.; Topkaya, S.N.; Hartati, Y.W. Label-free and label-based electrochemical detection of disease biomarker proteins. ADMET DMPK 2024, 12, 463–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Cavaco-Paulo, A. Effect of ultrasound on protein functionality. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 76, 105653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Camarillo, C.; Ocampo, E.A.; Casamichana, M.L.; Perez-Plasencia, C.; Alvarez-Sanchez, E.; Marchat, L.A. UV radiation and skin protein activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 13, 142–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, S.K. UV-induced immune suppression and chemoprevention. Cancer Lett. 2007, 255, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-W.; Kim, J.-H.; Yook, H.-S.; Kang, K.-O.; Lee, S.-Y.; Hwang, H.-J.; Byun, M.-W. Gamma radiation effects on milk proteins. J. Food Prot. 2001, 64, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanca, M.; Gaidau, C.; Zaharescu, T.; Balan, G.-A.; Matei, I.; Precupas, A.; Leonties, A.R.; Ionita, G. Gamma irradiation and protein structure. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, B.; Troszyńska, A. Enzymatic hydrolysis of cow’s whey proteins. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2005, 14, 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewska, B.; Karamać, M.; Amarowicz, R.; Szymkiewicz, A.; Troszyńska, A.; Kubicka, E. Immunoreactive properties of hydrolyzed whey peptides. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 39, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, B.; Jedrychowski, L.; Hajos, G.; Szabo, E. Alcalase and transglutaminase effects on whey proteins. Czech J. Food Sci. 2008, 26, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Han, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hui, T.; Ding, L.; Dai, W.; Han, Y.; Zheng, M.; Xing, G. Transglutaminase crosslinking and β-lactoglobulin. Molecules 2025, 30, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Xie, X.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, J.; Ma, M.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, D.; Lu, X.; Yang, G.; He, G. Cold plasma effects on celiac-toxic peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Qian, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L.; Raghavan, V.; Wang, J. Cold plasma and peanut protein immunore-activity. J. Future Foods. 2025, 6, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, C.A.; Zeindl, R.; Fernández-Quintero, M.L.; Tollinger, M.; Liedl, K.R. Allergenicity and Conformational Diversity of Allergens. Allergies 2024, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Jin, S.; Gang, D.D.; Yang, F. Analytical progress in house dust mite allergens. Rev. Environ. Health 2025, 40, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, D.; Appanna, R.; Santonicola, A.; De Bartolomeis, F.; Stellato, C.; Cianferoni, A.; Casolaro, V.; Iovino, P. Food allergy and intolerance: Nutritional concerns. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzhauser, T.; Röder, M. PCR Methods for Allergen Detection. In Handbook of Food Allergen Detection and Control; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2025; pp. 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lei, S.; Zou, W.; Wang, L.; Yan, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Q. Detection methods for food allergens. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 137, 106906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacorn, M.; Immer, U. ELISAs for Allergen Detection. In Handbook of Food Allergen Detection and Control; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2025; pp. 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchiz, A.; Sánchez-Enciso, P.; Cuadrado, C.; Linacero, R. Real-time PCR for peanut allergen detection. Foods 2021, 10, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engvall, E.; Perlmann, P. ELISA quantitation of antibodies. J. Immunol. 1972, 109, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuppo, L.; Giangrieco, I.; Tamburrini, M.; Alessandri, C.; Mari, A.; Ciardiello, M.A. Multiplex allergen microarray vs conventional methods. Foods 2022, 11, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelfi, A. Immunoassays/ELISA. In Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress: Basics and Measurement of Oxidative Stress; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzhauser, T.; Stephan, O.; Vieths, S. Hazelnut allergen detection: PCR-ELISA vs. sandwich-ELISA. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5808–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segundo-Acosta, P.S.; Oeo-Santos, C.; Benedé, S.; Ríos, V.d.L.; Navas, A.; Ruiz-Leon, B.; Moreno, C.; Pastor-Vargas, C.; Jurado, A.; Villalba, M.; et al. Proteomic profiling of food allergens. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 3052–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeberl, M.; Clarke, D.; Lopata, A.L. Food allergen detection via proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 3499–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.V.; Williams, K.M.; Ferguson, M.; Lee, D.; Sharma, G.M.; Do, A.B.; Khuda, S.E. Quantitative egg allergen ELISA. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1081, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.A.; Lopata, A.L.; Colgrave, M.L. Analytical methods for allergen control. Foods 2023, 12, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, S. (Ed.) Handbook of Food Allergen Detection and Control; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Thermo Fisher Scientific. ELISA Guide TR0065; Thermo Fisher Scientific: Waltham, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Engvall, E.; Perlmann, P. ELISA for IgG quantification. Immunochemistry 1971, 8, 871–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, Y.; Hamasaka, T.; Okada, H.; Nagashima, Y.; Morita, M. Improved multi-food allergen analysis of processed foods using HRAM-LC–MS/MS with an ELISA-validated extraction solution and MS sample prep kit. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 5165–5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, S.; Sun, L.; Zhao, J.; Huang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wan, S.; Pavase, T.R.; Li, Z. Sandwich ELISA for soybean allergens. Process Biochem. 2022, 117, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayla, M.E. ELISA detection of A2 milk. J. Adv. Res. Nat. Appl. Sci. 2023, 9, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasanayaka, B.P.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Yu, M.; Ahmed, A.M.M.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, H.; Wang, X. ELISA for fish protein antigenicity. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 112, 104690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Zheng, S.; Jin, X.; Chen, H.; Wu, Y. Developing a dual-antibody Sandwich ELISA and LFIA for detecting the cashew allergen Ana o 3 in foods. Food Chem. 2025, 472, 142942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Civera, A.; Galan-Malo, P.; Segura-Gil, I.; Mata, L.; Tobajas, A.P.; Sánchez, L.; Pérez, M.D. Development of sandwich ELISA and lateral flow immunoassay to detect almond in processed food. Food Chem. 2022, 371, 131338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Pramod, S.N.; Zhang, L.; Lin, H. Development of ELISA Method for Detecting Crustacean Major Allergen Tropomyosin in Processed Food Samples. Food Anal. Methods 2019, 12, 2719–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Song, S.; Zheng, Q.; Luo, P.; Wu, X.; Kuang, H. Development of a sandwich ELISA and immunochromatographic strip for the detection of shrimp tropomyosin. Food Agric. Immunol. 2019, 30, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Xu, L.; Dias, A.C.; Zhang, X. A sensitive sandwich ELISA using a modified biotin-streptavidin amplified system for histamine detection in fish, prawn and crab. Food Chem. 2021, 350, 129196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoormasti, R.S.; Fazlollahi, M.R.; Kazemnejad, A.; Movahedi, M.; Tayebi, B.; Yazdanyar, Z.; Azadi, Z.; Pourpak, Z.; Moin, M. Accuracy of immunoblotting assay for detection of specific IgE compared with ImmunoCAP in allergic patients. Electron. Physician 2018, 10, 6327–6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ansotegui, I.J.; Melioli, G.; Canonica, G.W.; Caraballo, L.; Villa, E.; Ebisawa, M.; Passalacqua, G.; Savi, E.; Ebo, D.; Gómez, R.M.; et al. IgE allergy diagnostics and other relevant tests in allergy, a World Allergy Organization position paper. World Allergy Organ. J. 2020, 13, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsonova, A.; Riabova, K.; Villazala-Merino, S.; Campana, R.; Niederberger, V.; Eckl-Dorna, J.; Fröschl, R.; Perkmann, T.; Zhernov, Y.V.; Elisyutina, O.G.; et al. Highly sensitive ELISA-based assay for quantification of allergen-specific IgE antibody levels. Allergy 2020, 75, 2668–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moritz, C.P.; Do, L.-D.; Tholance, Y.; Vallayer, P.-B.; Rogemond, V.; Joubert, B.; Ferraud, K.; La Marca, C.; Camdessanché, J.-P.; Honnorat, J.; et al. Conformation-stabilizing ELISA and cell-based assays reveal patient subgroups targeting three different epitopes of AGO1 antibodies. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 972161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, O.S.; Idoko, D.O.; Ogundipe, S.O.; Mensah, E. SDS-PAGE optimization for protein characterization. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2025, 10, 1008–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, D.; Yadav, P.; Yadav, M.; Jha, A. Analytical biotechnology tools. In Analytical Biotechnology: Tools and Applications. Am. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 17, 135–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, A.B.; Wobig, W.J.; Petering, D.H. Native SDS-PAGE for metal-bound proteins. Metallomics 2014, 6, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberstein, G.; Korol, L.; Righetti, P.G.; Bukshpan, S. SDS-PAGE Focusing: Preparative Aspects. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 8624–8630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, N. SDS-PAGE overview. Int. J. Chem. Sep. Technol. 2017, 3, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick, N.; Darie, C.C.; Hoelter, M.; Powers, G.; Johansen, J. 2D SDS-PAGE with Western Blot and MS. In Advancements of Mass Spectrometry in Biomedical Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindmark-Månsson, H.; Månsson, H.; Timgren, A.; Alden, G.; Paulsson, M. 2D gel electrophoresis of bovine milk proteins. Int. Dairy J. 2005, 15, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorri, Y. Vertical Isoelectric Focusing in 2D Electrophoresis. In Electrophoretic Separation of Proteins; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Haniu, H.; Komori, N. Determining Protein Molecular Weights via SDS-PAGE. In Electrophoretic Separation of Proteins; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Zienkiewicz, K.; Alché, J.d.D.; Zienkiewicz, A.; Tormo, A.; Castro, A.J. Identification of olive pollen allergens using a fluorescence-based 2D multiplex method. Electrophoresis 2015, 36, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez, L.; Barros, L.; Muñoz, S.; Medina, I. FTSC Labeling with 2DE-LC–MS/MS for Tissue Carbonyl Quantification. In Shotgun Proteomics: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, C.; Dhanapala, P.; Doran, T.; Tang, M.L.; Suphioglu, C. Molecular insights into food allergy. Mol. Immunol. 2016, 71, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, N.; Sircar, G.; Saha, B.; Pandey, N.; Bhattacharya, S.G. Proteomic dataset on allergen response. Data Brief. 2016, 7, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, N.; Halima, O.; Akhter, K.T.; Nuzhat, N.; Rao, R.S.P.; Wilson, R.S.; Ahsan, N. Proteomic characterization of low molecular weight allergens and putative allergen proteins in lentil (Lens culinaris) cultivars of Bangladesh. Food Chem. 2019, 297, 124936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allergome. Available online: https://www.allergome.org/script/search_step1.php?clear=1 (accessed on 1 February 2003).

- Ito, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Oyama, Y.; Tsuruma, R.; Saito, E.; Saito, Y.; Ozu, T.; Honjoh, T.; Adachi, R.; Sakai, S.; et al. Food allergen analysis for processed food using a novel extraction method to eliminate harmful reagents for both ELISA and lateral-flow tests. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 5973–5984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, R.; Tsuge, I.; Tokuda, R.; Teshima, R. Analysis of the distribution of rice allergens in brown rice grains and of the allergenicity of products containing rice bran. Food Chem. 2019, 276, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, S. Western Blot Analysis. In Nanotoxicity: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnasko, T.S.; Hnasko, R.M. The Western Blot. In ELISA: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai-Kastoori, L.; Schutz-Geschwender, A.R.; Harford, J.A. Quantitative Western blot analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2020, 593, 113608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sule, R.; Rivera, G.; Gomes, A.V. Western blotting: Theory and applications. Biotechniques 2023, 75, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurien, B.; Scofield, R. Western blotting. Methods 2006, 38, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeil, T.; Schwabl, U.; Ulmer, W.T.; König, W. Western blot of wheat flour allergens. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1990, 91, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Tao, X.; Liao, Y.; Yuan, C.; Lu, M.; Cui, Y. Tyr p 31 allergen characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 258, 128856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjos, L.; Loukissas, A.Z.; Power, D.M. Fish Muscle Proteomics and Allergen Detection. In Marine Genomics: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djeghim, H.; Benslama, O.; Ines, B.; Idoia, P.; Sanchez, P.; Douadi, K.; Alsaeedi, H.; Bechelany, M.; Barhoum, A. Integrated Detection and Computational Analysis of Allergens in Peanut Varieties Using 2-D Electrophoresis, Western Blotting. Lc-Ms/Ms Silico Approaches 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, E.; Di Bona, D.; Pilolli, R.; Loiodice, R.; Luparelli, A.; Giliberti, L.; D’uggento, A.M.; Rossi, M.P.; Macchia, L.; Monaci, L. In Vivo and In Vitro Assessment and Proteomic Analysis of the Effectiveness of Physical Treatments in Reducing Allergenicity of Hazelnut Proteins. Nutrients 2022, 14, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iddagoda, J.; Gunasekara, P.; Handunnetti, S.; Jeewandara, C.; Karunatilake, C.; Malavige, G.N.; de Silva, R.; Dasanayake, D. Identification of allergens in coconut milk and coconut oil in patients allergic to coconut milk. Sri Lance. Clin. Mol. Allergy 2022, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lyu, S.-C.; Nadeau, K.C.; McHugh, T. Identification of Almond (Prunus dulcis) Vicilin As a Food Allergen. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 67, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’ovidio, C.; Locatelli, M.; Perrucci, M.; Ciriolo, L.; Furton, K.G.; Gazioglu, I.; Kabir, A.; Merone, G.M.; de Grazia, U.; Ali, I.; et al. LC-MS/MS in pharmacotoxicology. Molecules 2023, 28, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merone, G.M.; Tartaglia, A.; Rossi, S.; Santavenere, F.; Bassotti, E.; D’Ovidio, C.; De Grazia, U. LC-MS/MS for illicit substance detection. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 16308–16313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campelo, J.D.M.; Rodrigues, T.B.; Costa, J.L.; Santos, J.M. QuEChERS optimization for antidepressant detection. Forensic Sci. Int. 2021, 319, 110660. [Google Scholar]

- Rubicondo, J.; Scuffi, L.; Pietrosemoli, L.; Mineo, M.; Terranova, F.; Bartucca, M.; Trignano, C.; Bertol, E.; Vaiano, F. LC–MS-MS screening of NPS and drugs in hair. J. Audiov. Transl. 2022, 46, e262–e273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosch, J.; Lesur, A.; Kler, S.; Bernardin, F.; Dittmar, G.; Francescato, E.; Hewings, S.J.; Jakwerth, C.A.; Zissler, U.M.; Heath, M.D.; et al. Allergen content in immunotherapy preparations. Toxins 2022, 14, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.E.; Chun, Y.; Jeong, S.; Jumreornvong, O.; Sicherer, S.H.; Bunyavanich, S. Oral microbiome and peanut allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs, M.L.; Johnson, P. Target selection for LC-MS/MS allergen methods. J. AOAC Int. 2018, 101, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New, L.S.; Stahl-Zeng, J.; Schreiber, A.; Cafazzo, M.; Liu, A.; Brunelle, S.; Liu, H.-F. Detection and Quantitation of Selected Food Allergens by Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry: First Action 2017.17. J. AOAC Int. 2020, 103, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagu, S.T.; Huschek, G.; Homann, T.; Rawel, H.M. Effect of Sample Preparation on the Detection and Quantification of Selected Nuts Allergenic Proteins by LC-MS/MS. Molecules 2021, 26, 4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Hu, X.-C.; Cai, Z.-P.; Voglmeir, J.; Liu, L. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Carbohydrate Modification on Glycoproteins from Seeds of Ginkgo biloba. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 7669–7679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, B.N.H.; Wilfred, A.; Venkatesh, Y.P. Emerging food allergens: Identification of polyphenol oxidase as an important allergen in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Immunobiology 2017, 222, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torii, A.; Seki, Y.; Arimoto, C.; Hojo, N.; Iijima, K.; Nakamura, K.; Ito, R.; Yamakawa, H.; Akiyama, H. Development of a simple and reliable LC-MS/MS method to simultaneously detect walnut and almond as specified in food allergen labelling regulations in processed foods. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, R.; Morello, S.; Lupi, S.; Vivaldi, B.; Bianchi, D.M.; Razzuoli, E. Allergens in Food: Analytical LC-MS/MS Method for the Qualitative Detection of Pistacia vera. Foods 2025, 14, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffendorf, C.; Mischlinger, J.; Dejon-Agobé, J.C.; Maïga-Ascofaré, O.; Ahenkan, E.; Adegnika, A.A.; Ramharter, M.; Wicha, S.G. Multiplex LC–MS/MS assay for simultaneous quantification of artesunate and its active metabolite dihydroartemisinin with pyronaridine, proguanil, cycloguanil, and clindamycin in pharmacokinetic studies. Malar. J. 2025, 24, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torii, A.; Seki, Y.; Sasano, R.; Ishida, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Ito, R.; Iwasaki, Y.; Iijima, K.; Akiyama, H. Development of a rapid and reliable method to simultaneously detect seven food allergens in processed foods using LC-MS/MS. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spörl, J.; Speer, K.; Jira, W. A rapid LC-MS/MS multi-method for the detection of 23 foreign protein sources from legumes, oilseeds, grains, egg and milk in meat products. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 124, 105628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akash, M.S.H.; Rehman, K. NMR Spectroscopy Overview. In Essentials of Pharmaceutical Analysis; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 439–532. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, L.D. Nuclear magnetic resonance. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. 1964, 19, 51–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fu, B.J.C.L.; Fu, L.; Cherayil, B.J.; Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Food Allergy; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomés, A.; Smith, S.A.; Chruszcz, M.; Mueller, G.A.; Brackett, N.F.; Chapman, M.D. Engineering allergenic epitopes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 153, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeindl, R.; Tollinger, M. NMR assignments of PR-10 allergens. Biomol. NMR Assign. 2021, 15, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeindl, R.; Unterhauser, J.; Röck, M.; Eidelpes, R.; Führer, S.; Tollinger, M. NMR Characterization of Food Allergens. In Food Allergens: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kleine-Tebbe, J.; Ballmer-Weber, B.K.; Breiteneder, H.; Vieths, S. Bet v 1 and its Homologs: Triggers of Tree-Pollen Allergy and Birch Pollen-Associated Cross-Reactions. In Molecular Allergy Diagnostics: Innovation for a Better Patient Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, M.; Meyer, B. Group Epitope Mapping by Saturation Transfer Difference NMR To Identify Segments of a Ligand in Direct Contact with a Protein Receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 6108–6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]