The Impact of Advertising Image Types on Consumer Purchasing Behavior of Fresh Agricultural Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

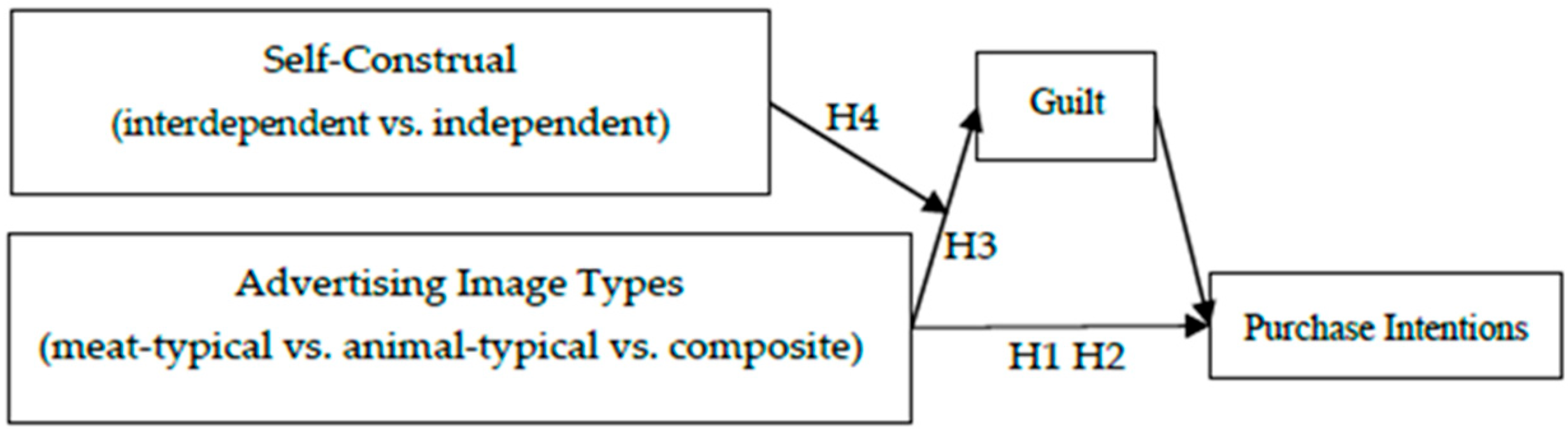

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Elaboration Likelihood Model

2.2. The Influence of Advertising Images on Purchase Intention

2.3. Moral–Emotion Routes: The Guilt Emotion Pathway

2.4. The Mediating Role of Guilt

2.5. Moderating Effect of Self-Construal

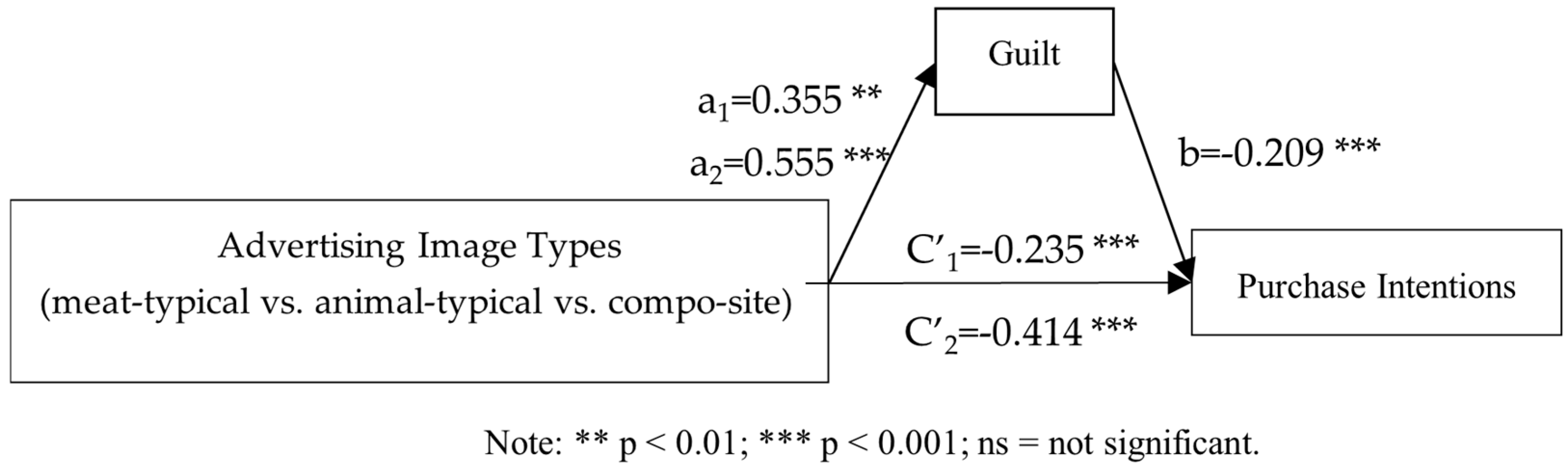

3. Experiment 1: The Impact of Advertising Image Types on Purchase Intentions and the Mediating Role of Guilt

3.1. Experimental Purpose

3.2. Experimental Sample and Design

3.3. Experimental Procedure

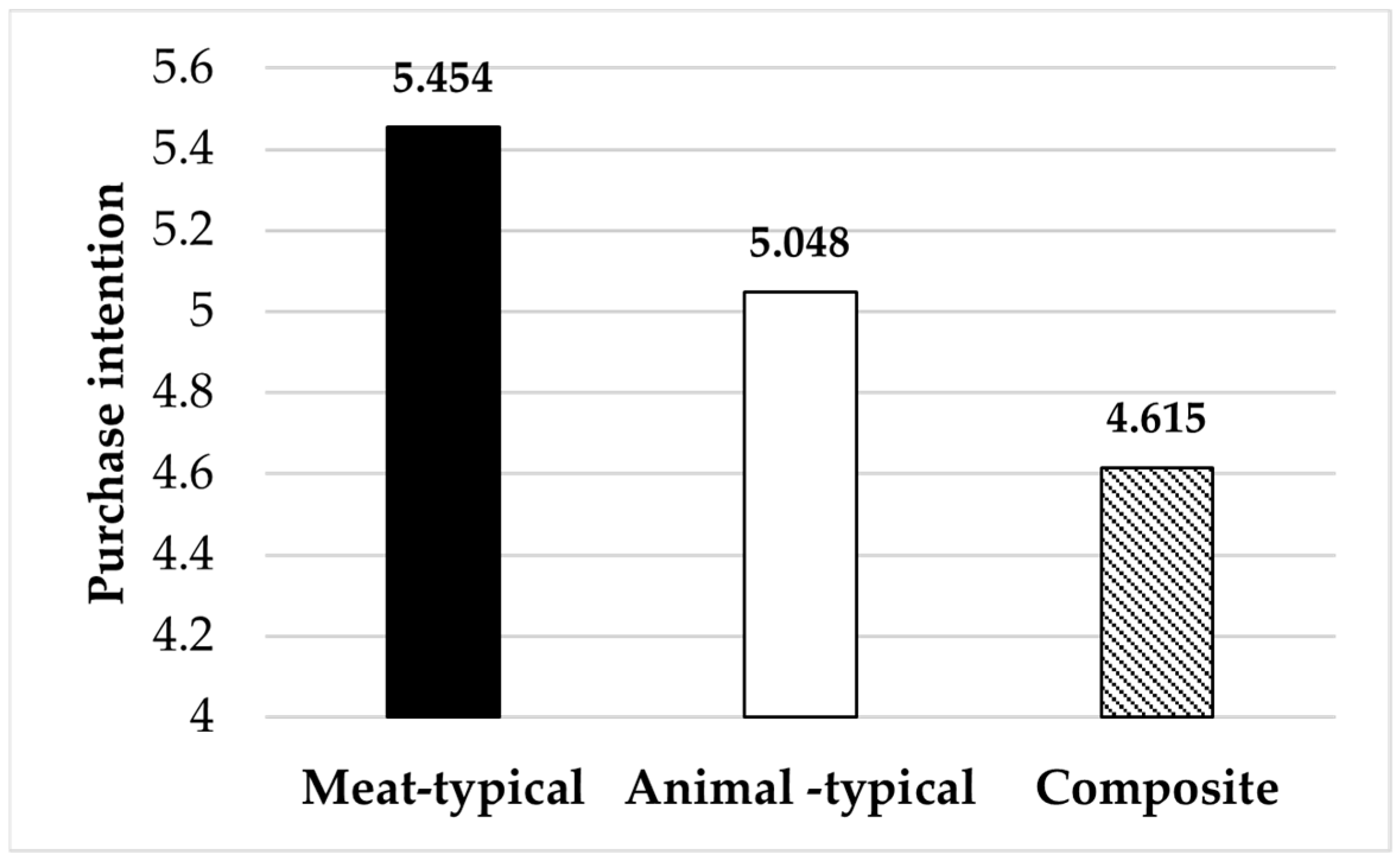

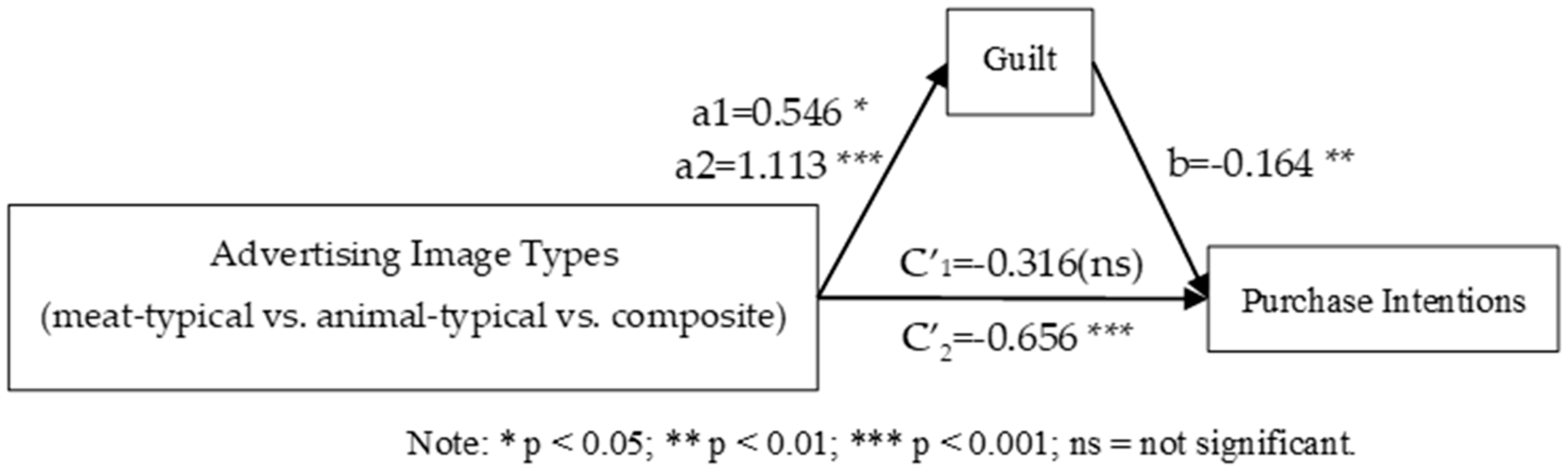

3.4. Results

3.5. Discussion

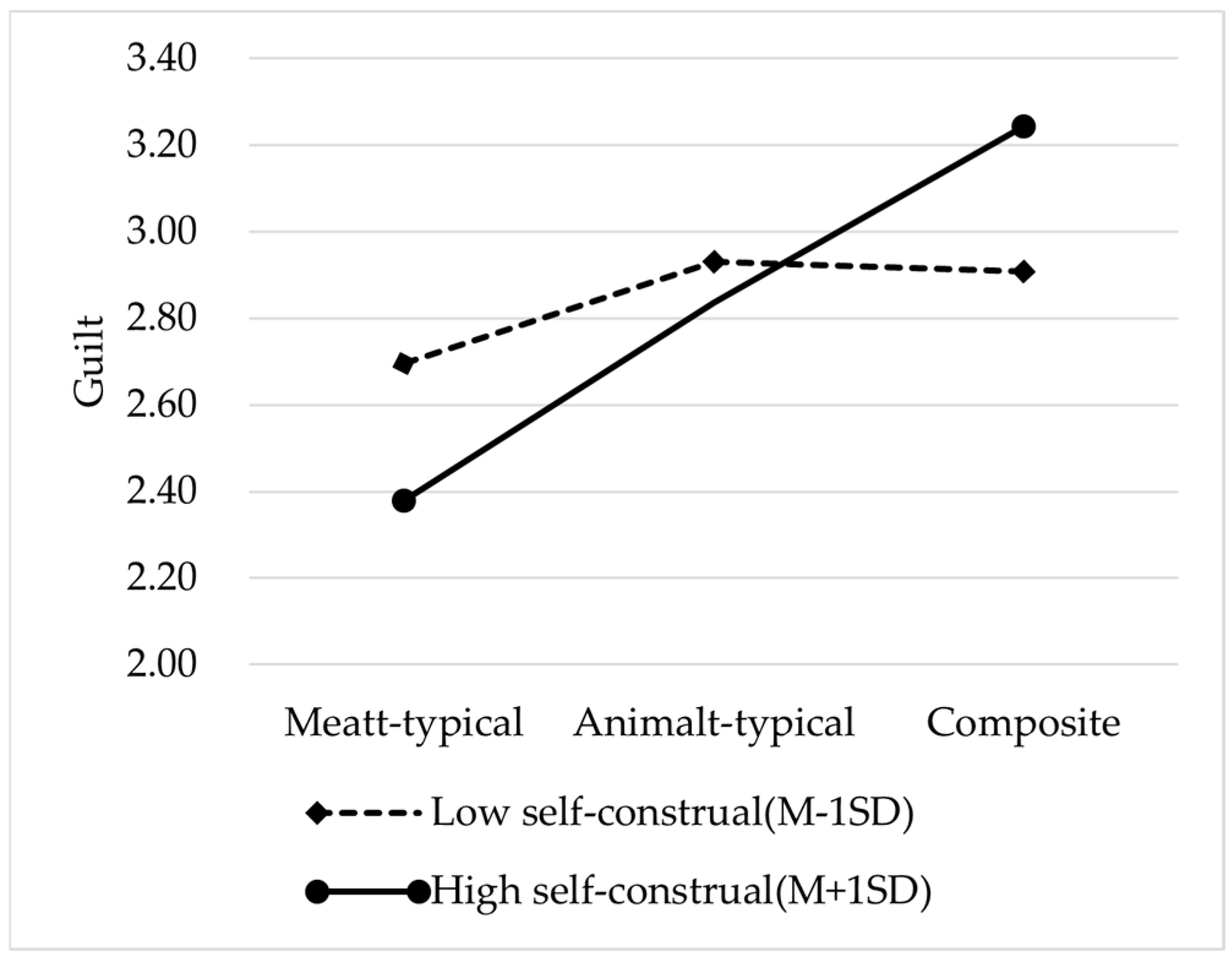

4. Experiment 2: The Moderating Role of Self-Construal in the Relationship Between Advertising Image Types and Purchase Intentions

4.1. Experimental Purpose

4.2. Experimental Sample and Design

4.3. Experimental Procedure

“You are participating in a badminton championship and have reached the finals. It is 3:32 p.m., and the sunlight shines on you. At this moment, you are the center of the world. You tell yourself: This is my battle; this is my opportunity. Regardless of winning or losing, I will prove my worth to myself.”

“You are participating in a badminton championship, and you will represent your team in the finals. It is 3:32 p.m., and the sunlight shines on you while your coach and teammates cheer for you. You tell yourself: This is our team’s battle; this is our team’s opportunity. Regardless of winning or losing, I will prove our value to my team.”

“Beef is a staple meat in daily life. Suppose you plan to purchase beef at a nearby fresh food supermarket; when you enter the meat section, you see the advertisement displayed above the counter.”

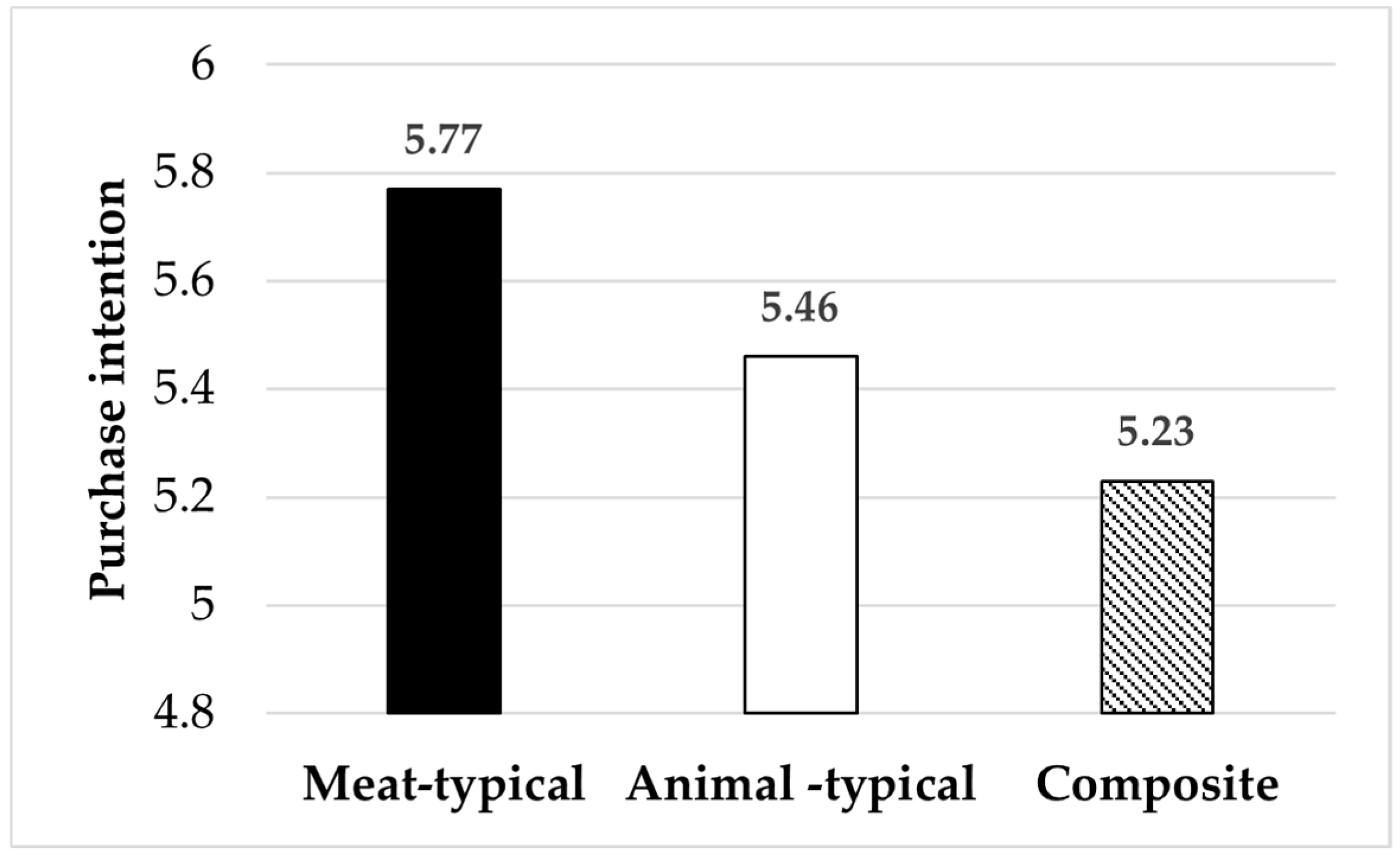

4.4. Results

4.5. Discussion

5. General Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Contributions

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Summary of Measurement Items

| Construct | Measurement Items (Seven-Point Scales) | Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| Purchasing intention |

| Experiment 1 |

| Purchasing intention |

| Experiment 2 |

| Guilt |

| Experiment 1 Experiment 2 |

| Disgust |

| Experiment 1 Experiment 2 |

Appendix B. Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

| Measurement Items | Factor | Standardized Loading | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| The happiness of my team members is important to me. | Interdependent Self-Construal | 0.740 | <0.001 |

| It is important to maintain harmony within the team. | 0.698 | <0.001 | |

| My happiness largely depends on the happiness of those around me. | 0.736 | <0.001 | |

| If my family disapproves, I am willing to give up an activity I really enjoy. | 0.584 | <0.001 | |

| Even if I strongly disagree with group members, I try to avoid conflict. | 0.580 | <0.001 | |

| If they need me, I would stay in a group even if I do not like it. | 0.584 | <0.001 | |

| Respecting the group’s decision is important to me. | 0.536 | <0.001 | |

| My personal identity is independent of others, and this is very important to me. | Independent Self-Construal | 0.760 | <0.001 |

| I like to be different from others in many ways. | 0.689 | <0.001 | |

| I am unique. | 0.555 | <0.001 | |

| I would rather say “no” directly to others than risk being misunderstood. | 0.458 | <0.001 | |

| I enjoy working in situations where I am in competition with others. | 0.507 | <0.001 | |

| Competition is the law of nature. | 0.604 | <0.001 | |

| When discussing with others, I prefer to be straightforward. | 0.802 | <0.001 |

References

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Meat and Seafood Production & Consumption. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/meat-and-seafood-production-consumption (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Loughnan, S.; Haslam, N.; Bastian, B. The role of meat consumption in the denial of moral status and mind to meat animals. Appetite 2010, 55, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, J.R.; Hohle, S.M. Meat eaters by dissociation: How we present, prepare and talk about meat increases willingness to eat meat by reducing empathy and disgust. Appetite 2016, 105, 758–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozin, P.; Markwith, M.; Stoess, C. Moralization and becoming a vegetarian: The transformation of preferences into values and the recruitment of disgust. Psychol. Sci. 1997, 8, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. Application of animal anthropomorphic images mixed with graffiti style in packaging design. Xin Mei Yu 2022, 10, 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L. Application of animal images in food packaging design: Taking traditional Tibetan auspicious patterns as an example. Green Packag. 2021, 6, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Park, J. “Human-like” is powerful: The effect of anthropomorphism on psychological closeness and purchase intention in insect food marketing. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 109, 104901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, S. The influence of visual marketing on consumers’ purchase intention of fast fashion brands in China—An exploration based on fsQCA method. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1190571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, M.A.; Belgiawan, P.F. Designing Instagram Advertisement Content: What Design Elements Influence Customer Attitude and Purchase Behavior? Contemp. Manag. Res. 2023, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.M.; Yoon, S. Guilt of the meat-eating consumer: When animal anthropomorphism leads to healthy meat dish choices. J. Consum. Psychol. 2021, 31, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, B.; Loughnan, S.; Haslam, N.; Radke, H.R. Don’t mind meat? The denial of mind to animals used for human consumption. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, H. Negative emotions and attitudes in anthropomorphic advertising based on human authenticity: The mediating role of guilt. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2017, 49, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubberød, E.; Dingstad, G.I.; Ueland, O.; Risvik, E. The effect of animality on disgust response at the prospect of meat preparation—An experimental approach from Norway. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Schumann, D. Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, R.L.; Klein, N.M. Packaging as brand communication: Effects of product pictures on consumer responses to the package and brand. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2002, 10, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silayoi, P.; Speece, M. Packaging and purchase decisions: An exploratory study on the impact of involvement level and time pressure. Br. Food J. 2004, 106, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Sadachar, A. “Why Should I Buy Sustainable Apparel?” Impact of User-Centric Advertisements on Consumers’ Affective Responses and Sustainable Apparel Purchase Intentions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, X.; Antille, N.; de Lavergne, M.D.; Moccand, C.; Labbe, D. Impact of visual cues on consumers’ freshness perception of prepared vegetables. Foods 2024, 13, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.J. The sexual politics of meat. In Living with Contradictions; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 548–557. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, N. The Civilizing Process: The History of Manners; The Wilson Quarterly: Washington, DC, USA, 1978; Volume 1, pp. 970–989. [Google Scholar]

- Kubberød, E.; Ueland, O.; Dingstad, G.I.; Risvik, E.; Henjesand, I.J. The effect of animality in the consumption experience—A potential for disgust. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2008, 14, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. The interaction between contemporary discourse and historical narrative: The value logic of China’s modern advertising industry under the background of “telling China’s stories”. Xinwen Yu Chuanbo Pinglun 2019, 3, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. A Study and Practice on the Typical Characteristics of Advertising Images: Advertising Practice Works such as “Jieting Sanitary Napkins”. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Normal University, Harbin, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, M.; Cheng, Y. Narrative characteristics of advertising images. Xinwen Aihào Zhe 2010, 2, 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, G.; Xia, Q.; Yue, B. Effectiveness of green advertising from the perspective of image proximity. Xinwen Yu Chuanbo Pinglun 2020, 73, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, T.P.; Wang, M.; Leach, S.; Siu, H.L.; Khanna, M.; Chan, K.W.; Chau, H.T.; Tam, K.Y.Y.; Feldman, G. Revisiting the motivated denial of mind to animals used for food: Replication registered report of Bastian et al. (2012). Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 37, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradidge, S.; Zawisza, M.; Harvey, A.J.; McDermott, D.T. A structured literature review of the meat paradox. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 16, e5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechner, D.; Isbanner, S. Understanding the intention–behaviour gap in meat reduction: The role of cognitive dissonance in dietary change. Appetite 2025, 214, 108204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidou, M.; Lesk, V.; Stewart-Knox, B.; Francis, K.B. Moral emotions and justifying beliefs about meat, fish, dairy and egg consumption: A comparative study of dietary groups. Appetite 2023, 186, 106544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, E.P.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Onwezen, M.C.; Taufik, D. “Do you consider animal welfare to be important?” activating cognitive dissonance via value activation can promote vegetarian choices. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 83, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P.; Fallon, A.E. A perspective on disgust. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, A.; Machry, K.; Levinson, C.A. Disgust, shame, and guilt: Examining unique relationships with eating disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Eat. Behav. 2025, 58, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Stuewig, J.; Mashek, D.J. Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 345–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiulio, A.M.; Gaylin, W. Feelings: Our vital signs. Educ. Res. 1979, 24, 596–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.A.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, W.; Yang, Z.; Su, X. Too anthropomorphized to keep distance: The role of social psychological distance on meat inclinations. Appetite 2024, 196, 107272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.P.; Weick, M.; Vasiljevic, M. Impact of pictorial warning labels on meat meal selection: A randomised experimental study with UK meat consumers. Appetite 2023, 190, 107026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, M.; Hodson, G.; Dhont, K.; MacInnis, C. Eating with our eyes (closed): Effects of visually associating animals with meat on antivegan/vegetarian attitudes and meat consumption willingness. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2019, 22, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothgerber, H. Meat-related cognitive dissonance: A conceptual framework for understanding how meat eaters reduce negative arousal from eating animals. Appetite 2020, 146, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Jones, E.; Mills, J. Cognitive Dissonance: Progress on a Pivotal Theory in Social Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Redwood, CA, USA, 1957; Volume 72, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones, E.; Harmon-Jones, C. Cognitive dissonance theory after 50 years of development. Z. Sozialpsychol. 2007, 38, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.S.; Doan, T.T.T. The Impact of Regulatory Focus and Self-Construal on Guilt versus Shame Arousals in Health Communications: An Empirical Study from Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2022, 9, 387–397. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, E.Y.; Septianto, F. Self-construals and health communications: The persuasive roles of guilt and shame. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 170, 114357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, B.; Frijda, N.H. Emotion and Culture: Beyond Universalism. In Emotion and Culture: Beyond Universalism; Mesquita, B., Frijda, N.H., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.E.; Morris, M.L.; Gore, J.S. Thinking about oneself and others: The relational–interdependent self-construal and social cognition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Lee, S.W. Does culture influence what and how we think? Effects of priming individualism and collectivism. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 311–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafimow, D.; Triandis, H.C.; Goto, S.G. Some tests of the distinction between the private self and the collective self. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, R.E.; Peng, K.; Choi, I.; Norenzayan, A. Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 108, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S.; Kim, H. Temporal duration and attribution process of cause-related marketing: Moderating roles of self-construal and product involvement. Int. J. Advert. 2018, 37, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnen, U.; Oyserman, D. Thinking about the self influences thinking in general: Cognitive consequences of salient self-concept. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 38, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, R.E.; Miyamoto, Y. The influence of culture: Holistic versus analytic perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monga, A.S.; John, D.R. Cultural differences in brand extension evaluation: The influence of analytic versus holistic thinking. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 33, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, S. The effect of self-construal on spatial judgments. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.; Aaker, J.L. Bringing the frame into focus: The influence of regulatory fit on processing fluency and persuasion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemer, H.; Shavitt, S.; Koo, M.; Markus, H.R. Preferences don’t have to be personal: Expanding attitude theorizing with a cross-cultural perspective. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 121, 619–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalwani, A.K.; Shavitt, S. You get what you pay for? Self-construal influences price–quality judgments. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Yang, Z.; Mourali, M. Consumer adoption of new products: Independent versus interdependent self-perspectives. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Jiang, Y.; Miao, M.; Wang, Y. The effect of vividness of anthropomorphic advertising images based on different visual object structures on consumers’ product attitudes. J. Inf. Syst. 2019, 1, 68–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tudrej, B.; Bernard, A.; Delaunay, B.; Bernard, A.; Dupuy, A.; Malavergne, C.; Bacon, T.; Sebo, P.; Maisonneuve, H. Translation and validation of the meat attachment questionnaire (MAQ) in a French general practice population. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoons, F. Eat Not This Flesh: Food Avoidances from Prehistory to the Present, 2nd ed.; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Angyal, A. Disgust and related aversions. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1941, 36, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means–end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonetti, P.; Maklan, S. Feelings that make a difference: How guilt and pride convince consumers of the effectiveness of sustainable consumption choices. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xie, T.; Zhan, C. The negative impact of anthropomorphic avatars of intelligent customer service in service failure contexts: The mediating mechanism of disgust. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2021, 24, 194–206. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, M. Mediation analysis of categorical variables. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 40, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L.; Lee, A.Y. “I” seek pleasures and “we” avoid pains: The role of self-regulatory goals in information processing and persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Xu, Q. Preliminary application of the Chinese version of the Self-Construal Scale (SCS). Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 16, 602–604. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Wen, Z.; He, Z. Moderated mediation model analysis of common categorical variables. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 29, 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, K.F.; Sintov, N.D. Guilt consistently motivates pro-environmental outcomes while pride depends on context. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 80, 101776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.S.; Gamborg, C.; Lund, T.B. Eco-guilt and eco-shame in everyday life: An exploratory study of the experiences, triggers, and reactions. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1357656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, X. Traceable pork: Information combination and consumer willingness to pay. Chin. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2014, 24, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Wang, S.; Hu, W. Consumer preferences and willingness to pay for traceable food attributes: A case study of pork. Chin. Rural Econ. 2014, 8, 58–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, R.; Hou, B.; Chen, X. Analysis of consumers’ willingness to pay for traceable food information attributes: A case study of pork. Chin. Rural Econ. 2016, 11, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.A. The effect of verbal and visual components of advertisements on brand attitudes and attitude toward the advertisement. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edell, J.A.; Staelin, R. The information processing of pictures in print advertisements. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.M.M.I.; Olsen, G.D.; Pracejus, J.W. Affective responses to images in print advertising: Affect integration in a simultaneous presentation context. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madzharov, A.V.; Block, L.G. Effects of product unit image on consumption of snack foods. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Han, X.; Li, C.; Geng, N.; Yu, M. The influence of traceability label trust on consumers’ traceability pork purchasing behavior: Based on the moderating effect of food safety identification. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, M.; Yeh, C.H.; Chatzopoulou, E.; White, J.; Tocco, B.; Hubbard, C.; Hallam, F. Consumers’ willingness to pay for an animal welfare food label. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 209, 107852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, F.; Gu, Y.; Bai, Z.; Dong, Y. The Impact of Advertising Image Types on Consumer Purchasing Behavior of Fresh Agricultural Products. Foods 2025, 14, 3915. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223915

Huang F, Gu Y, Bai Z, Dong Y. The Impact of Advertising Image Types on Consumer Purchasing Behavior of Fresh Agricultural Products. Foods. 2025; 14(22):3915. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223915

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Fan, Yumeng Gu, Zhonghu Bai, and Yani Dong. 2025. "The Impact of Advertising Image Types on Consumer Purchasing Behavior of Fresh Agricultural Products" Foods 14, no. 22: 3915. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223915

APA StyleHuang, F., Gu, Y., Bai, Z., & Dong, Y. (2025). The Impact of Advertising Image Types on Consumer Purchasing Behavior of Fresh Agricultural Products. Foods, 14(22), 3915. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223915