Consumer Perceptions of Botanical Sources of Nutrients: A UK-Based Visual Focus Group Study Exploring Perceptions of Nettles (Urtica dioica) as a Sustainable Food Source

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Screening Questionnaire

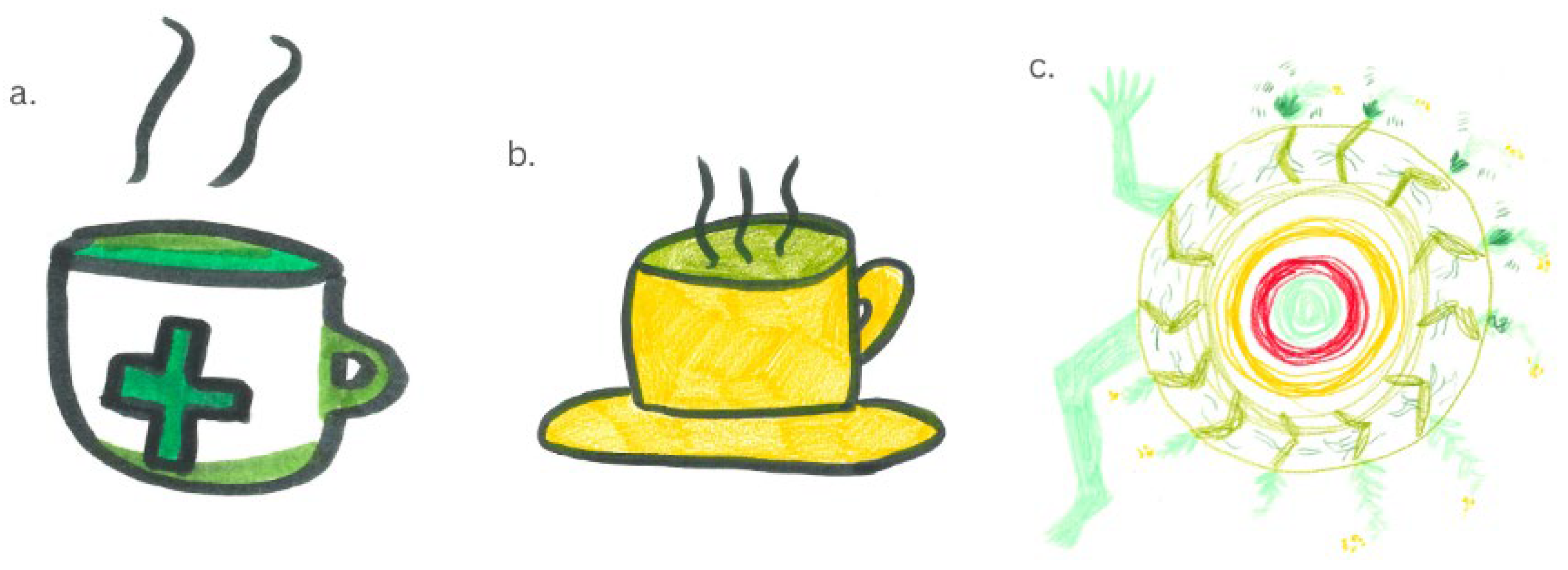

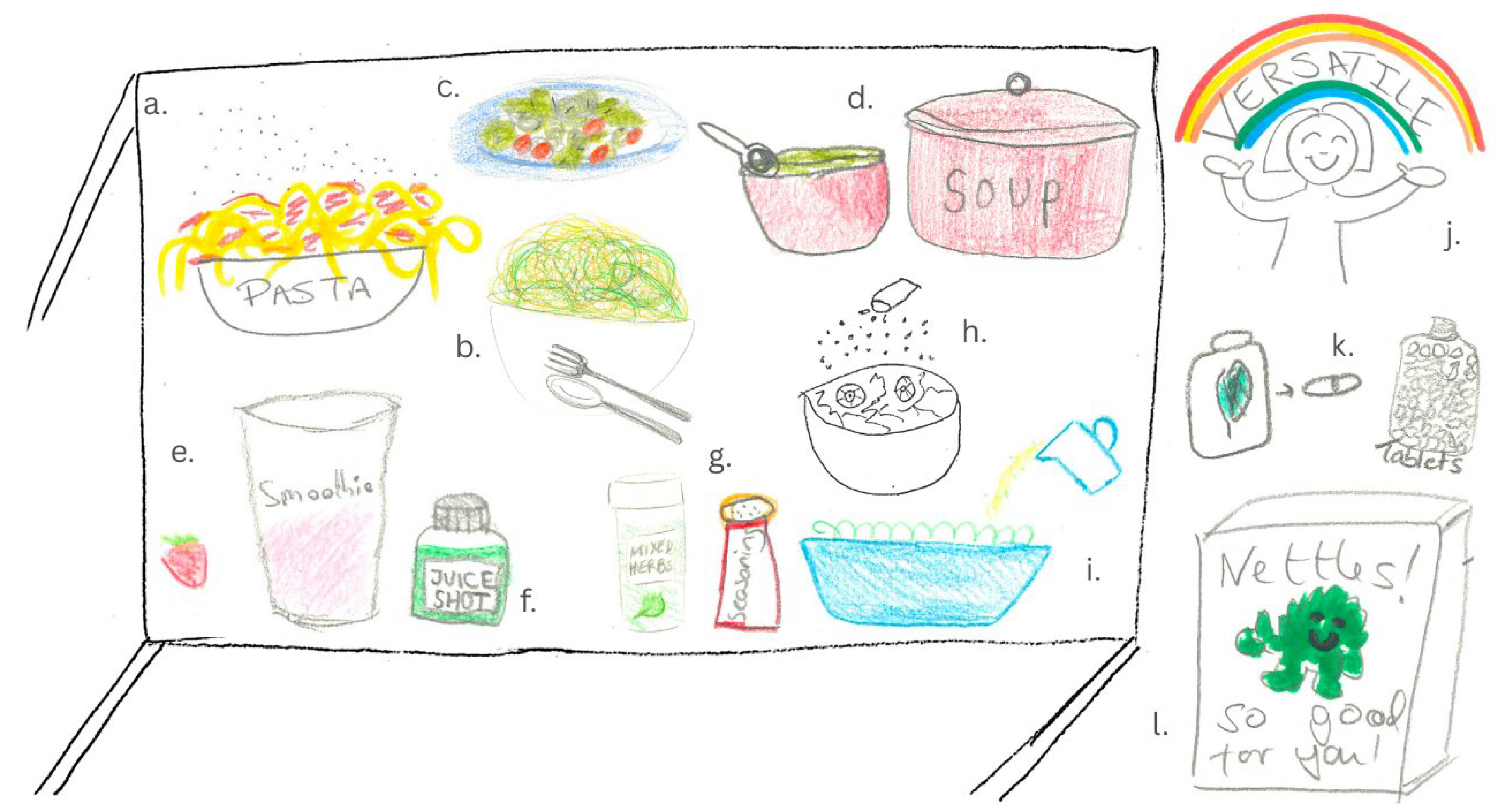

2.2.2. Visual Focus Groups

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: “Why Would You Want to Eat a Cactus?” “It’s Healthy for You”: Familiarity with Consuming Nettles

3.1.1. Sub-Theme 1: Never Heard of Eating Nettles

“There’s a horrible texture that you would associate with it. […] Yeah, definitely. Because that’s the whole thing is the texture of it. Because it like gives you bumps and makes you itch and things.”

3.1.2. Sub-Theme 2: Heard of Eating Nettles but Not Tried Them

“My nan recommended drinking it one time […] and I passed […] it was around spring when I was getting hay fever bad, so she was like, “This will help,” and I was like, “I’ll just suffer.”

“I think it’s more like, experience with nettles is they’re painful. So then the idea of something, they’re like, “Drink this painful drink.” It’s like, “Danger juice.”

“I’m thinking it’s warm and cosy […] I only knew about soup and that last year.”

3.1.3. Sub-Theme 3: Tried Eating Nettles

“I liked it. I enjoy it. I think it has that kind of earthy maybe tones and definitely not sweet. And I enjoy all those kinds of stuff, especially if they are taken from a field or something. I come from Poland, so maybe like we’re like taking all different kind of like flowers and leaves and stuff, drying them out and taking them. And I enjoy things like that myself.”

3.2. Theme 2: “Disguise It in Your Own Way” “Done and Dusted”: Sensory Attributes and Convenience Influences Format

“[…] I think the, like, benefits of it make me think of perhaps wanting to cook it into comfort food as well. So, you know, the things that you really love, and then adding something as well, where you know it’s not just the psychological benefits that you’re eating this meal, it makes you feel good. You know that you can have all these, like, dose of vitamins as well.”

“I said that we could add it to salads. That’s how I would personally use it as long as it was tasteless and it didn’t affect the salad. In the form of a tea, if it could be like shaken up and then put it into a tea or something like that. Or added to like a soup that’s already your favourite and it wasn’t going to add anything except for nutritional value to it.”

“If you were to sprinkle it on something you’d imagine it wouldn’t necessarily taste of much.”

“I think a capsule could be beneficial for people who are busy or don’t have time to incorporate it in their cooking or anything like that. It’s easy to take. It would be done and dusted without having to do anything else.”

“Like having it in a vitamin form or a gummy because then you just have it, you don’t have to worry about the taste or how much extra in […] Like making it in that form or you buying it in that form? […] Buying in that form, yeah. And then its already, you don’t have to worry about how much you use. It’s already done for you, you just take it as a multi-vitamin.”

3.3. Theme 3: “I Can’t See Why Anyone Wouldn’t Take It” “There Are Nicer Things to Drink” It Might Be Healthy but…

“[…] convincing people that it would actually be good, because most of our, initial reactions was—[…] negativity in general, or pain or disgust. So, that would be a big issue, it’s just general perceptions.”

3.3.1. Sub-Theme One: … It Will Not Be Nice to Eat

“And there are so many other [options], like, they say about the health benefits, but there are nicer things to drink to get it, so why would I go for something that has bad connotations?”

“I don’t care if it tastes bad, if I really need it.”

3.3.2. Sub-Theme Two: … It Is Ultra-Processed Which Reduces Its Healthiness

“Well, I know about potatoes.”

“And I was just thinking about how much of the potato starch that you have in that, versus the actual nettles. So, it is just like 5 percentage of the nettle and then 95 or something else. Why would I have the actual pill, you know, I might as well just have the leaf?”

“They can’t be that horrid or awful if they’ve been used in other things already.”

3.3.3. Sub-Theme Three: … It Is Too Expensive and Difficult to Find

“I’d like to think it would be reasonably priced just because it is easy to grow and harvest nettles.”

“And then if it was accessible, like if it was in easily to access in [global brand] or it was in your general supermarket rather than you having to go to [UK health food shop brand name] and like fish through all the other supplements that it was just there on the shelf as a powder that you can spread on your salad and on the package it said it helps with arthritis say for example. And then people would be like right I’ll try that and see if it helps.“

3.3.4. Sub-Theme Four… I Do Not Know How Much to Consume

“The thing about powder, I would think, when you’re talking about the negative about the powder that you can now use, it’s going to be a minimal amount, when it’s dry too. So, it’s getting the right, correct measurement. […] Whereas in the capsule you don’t have to worry about the amount.”

3.3.5. Sub-Theme Five… I Do Not Trust the Health Claims

“But I also concern if it’s in powder form. Would it affect the effectiveness of the ingredient to my body? So, I would like, I think I would just read the studies and see what kind of, what in what form that the, I don’t know if it’s a trial or something that the participants take during that trial and then see if that’s powder. (Participant 2: Yeah.) And then that’s, I’ll know it’s effective because they’re using the same thing I’m using.”

“If you want to market it, it would have to be, as broad as possible, if that makes sense? Because, you know, if it just said, benefits arthritis, then I feel like I wouldn’t be too keen on it. Or my people, my age demographic wouldn’t be too… into that. But if it was like, antioxidant, has these vitamins, it does this and this it would be a bit more enticing I suppose?”

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GHG | Green House Gas |

| SFC | Sustainable Food Consumption |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UN | United Nations |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behaviour |

| EFSA | European Food Standards Agency |

References

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Campbell, B.M.; Ingram, J.S.I. Climate Change and Food Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F.N.; Leip, A. Food Systems Are Responsible for a Third of Global Anthropogenic GHG Emissions. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuckler, D.; Nestle, M. Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, K.; Wieck, C.; Rudloff, B. Sustainable Food Consumption and Sustainable Development Goal 12: Conceptual Challenges for Monitoring and Implementation. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milford, A.B.; Le Mouël, C.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Rolinski, S. Drivers of Meat Consumption. Appetite 2019, 141, 104313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzgys, S.; Pickering, G.J. Perceptions of a Sustainable Diet among Young Adults. Environ. Educ. Res. 2024, 31, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; WHO. Sustainable Healthy Diets-Guiding Principles; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Shukla, P.R., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C.; Barioni, L.G.; Benton, T.G.; Herrero, M.; Krishnapillai, M.; Liwenga, E.; Pradhan, P.; Rivera-Ferre, M.G.; Sapkota, T.; et al. Food Security. In Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 437–550. ISBN 9781009157988. [Google Scholar]

- Galanakis, C.M. The Future of Food. Foods 2024, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijksterhuis, G.; Wallner, M. Eight Easy Pieces: Challenges for the Science of Food Perception and Behaviour. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 159, 104985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cueto, F.J.A. Sustainability, Health and Consumer Insights for Plantbased Food Innovation. Int. J. Food Des. 2020, 5, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardello, A.V.; Schutz, H.G.; Lesher, L.L. Consumer Perceptions of Foods Processed by Innovative and Emerging Technologies: A Conjoint Analytic Study. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2007, 8, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hässig, A.; Hartmann, C.; Sanchez-Siles, L.; Siegrist, M. Perceived Degree of Food Processing as a Cue for Perceived Healthiness: The NOVA System Mirrors Consumers’ Perceptions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 110, 104944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrus, R.R.; do Amaral Sobral, P.J.; Tadini, C.C.; Gonçalves, C.B. The NOVA Classification System: A Critical Perspective in Food Science. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren-Walker, A.; Beckmann, M.; Watson, A.; McAllister, S.; Lloyd, A.J. Effect of Thermal Processing by Spray Drying on Key Ginger Compounds. Metabolites 2025, 15, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, S.; Sánchez-Siles, L.M.; Siegrist, M. The Importance of Food Naturalness for Consumers: Results of a Systematic Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, H.P.; Paudel, K.R.; Khanal, S.; Baral, A.; Panth, N.; Adhikari-Devkota, A.; Jha, N.K.; Das, N.; Singh, S.K.; Chellappan, D.K.; et al. Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica L.): Nutritional Composition, Bioactive Compounds, and Food Functional Properties. Molecules 2022, 27, 5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, P.; Bogati, S.; Joshi, D.; Shah, P. A Review on Stinging Nettle: Medicinal and Traditional Uses. Matrix Sci. Pharma 2023, 7, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauso, L.; de Falco, B.; Lanzotti, V.; Motti, R. Stinging Nettle, Urtica dioica L.: Botanical, Phytochemical and Pharmacological Overview. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 1341–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toplicean, I.M.; Ianuș, R.D.; Datcu, A.D. An Overview on Nettle Studies, Compounds, Processing and the Relation with Circular Bioeconomy. Plants 2024, 13, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinelli, P.; Ieri, F.; Vignolini, P.; Bacci, L.; Baronti, S.; Romani, A. Extraction and HPLC Analysis of Phenolic Compounds in Leaves, Stalks, and Textile Fibers of Urtica dioica L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 9127–9132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Virgilio, N.; Papazoglou, E.G.; Jankauskiene, Z.; Di Lonardo, S.; Praczyk, M.; Wielgusz, K. The Potential of Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica L.) as a Crop with Multiple Uses. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 68, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kregiel, D.; Pawlikowska, E.; Antolak, H. Urtica Spp.: Ordinary Plants with Extraordinary Properties. Molecules 2018, 23, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Foods Standards Agency Health Claims. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/health-claims-art-13 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Saeed Ahmad, S.; Javed, S. Exploring the Economic Value of Underutilized Plant Species in Ayubia National Park. Pak. J. Bot. 2007, 39, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar]

- Shonte, T.T.; W/Tsadik, K. Indigenous Knowledge and Consumer’s Perspectives of Stinging Nettle (Urtica Simensis) in the Central and Southeastern Highlands of Oromia Regional States of Ethiopia. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-809967/v1 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Bhusal, K.K.; Magar, S.K.; Thapa, R.; Lamsal, A.; Bhandari, S.; Maharjan, R.; Shrestha, S.; Shrestha, J. Nutritional and Pharmacological Importance of Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica L.): A Review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, M.; Khoshkhat, P.; Chamani, M.; Shahsavari, S.; Dorkoosh, F.A.; Rajabi, A.; Maniruzzaman, M.; Nokhodchi, A. In-Depth Multidisciplinary Review of the Usage, Manufacturing, Regulations & Market of Dietary Supplements. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 67, 102985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Murga, L.; Garcia-Alvarez, A.; Roman-Viñas, B.; Ngo, J.; Ribas-Barba, L.; van den Berg, S.J.P.L.; Williamson, G.; Serra-Majem, L. Plant Food Supplement (PFS) Market Structure in EC Member States, Methods and Techniques for the Assessment of Individual PFS Intake. Food Funct. 2011, 2, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, S.A.O.; Ashaolu, T.J.; Babu, A.S. Food Drying: A Review. Agric. Rev. 2022, 46, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, S.; Rac, V.; Manojlovi, V.; Raki, V.; Bugarski, B.; Flock, T.; Krzyczmonik, K.E.; Nedovi, V. Limonene Encapsulation in Alginate/Poly (Vinyl Alcohol). Procedia Food Sci. 2011, 1, 1816–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Alvarez, A.; Egan, B.; De Klein, S.; Dima, L.; Maggi, F.M.; Isoniemi, M.; Ribas-Barba, L.; Raats, M.M.; Meissner, E.M.; Badea, M.; et al. Usage of Plant Food Supplements across Six European Countries: Findings from the Plantlibra Consumer Survey. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeurissen, S.M.F.; Buurma-Rethans, E.J.M.; Beukers, M.H.; Jansen-van der Vliet, M.; van Rossum, C.T.M.; Sprong, R.C. Consumption of Plant Food Supplements in the Netherlands. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.M.; Bajracharya, A.; Shrestha, A.K. Comparison of Nutritional Properties of Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) Flour with Wheat and Barley Flours. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 4, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, C.; Embling, R.; Neilson, L.; Randall, T.; Wakeham, C.; Lee, M.D.; Wilkinson, L.L. Consumer Knowledge and Acceptance of “Algae” as a Protein Alternative: A UK-Based Qualitative Study. Foods 2022, 11, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, E. Visual Focus Groups: Stimulating Reflexive Conversations with Collective Drawing. New Media Soc. 2024, 26, 5486–5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnoli, A. Beyond the Standard Interview: The Use of Graphic Elicitation and Arts-Based Methods. Qual. Res. 2009, 9, 547–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, L.; Ploeger, A.; Strassner, C. Participative Processes as a Chance for Developing Ideas to Bridge the Intention-Behavior Gap Concerning Sustainable Diets. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample Sizes for Saturation in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review of Empirical Tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, T.; Cousins, A.L.; Neilson, L.; Price, M.; Hardman, C.A.; Wilkinson, L.L. Sustainable Food Consumption across Western and Non-Western Cultures: A Scoping Review Considering the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 114, 105086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M.; Lohmann, S.; Albarracin, D. The Influence of Attitudes on Behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes, Volume 1: Basic Principles, 2nd ed.; Albarracin, D., Johnson, B.T., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 197–255. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, R. Rhetoric of the Image (S. Heath, Trans.). In Image, Music, Text (S. Heath, Trans.); Fontana Press: London, UK, 1977; pp. 32–51. [Google Scholar]

- Grange, H.; Lian, O.S. “Doors Started to Appear:” A Methodological Framework for Analyzing Visuo-Verbal Data Drawing on Roland Barthes’s Classification of Text-Image Relations. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2022, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, M.V.; Wu, S.; Zhu, M. What Is a Picture Worth? A Primer for Coding and Interpreting Photographic Data. Qual. Soc. Work 2017, 16, 810–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2022, 9, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, T.; Jewitt, C. Semiotics and Iconography. In The Handbook of Visual Analysis; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2004; pp. 92–118. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, P. Content Analysis of Visual Images. In The Handbook of Visual Analysis; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2004; pp. 10–34. [Google Scholar]

- Di Tizio, A.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Quave, C.L.; Redžić, S.; Pieroni, A. Traditional Food and Herbal Uses of Wild Plants in the Ancient South-Slavic Diaspora of Mundimitar/Montemitro (Southern Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2012, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, G.; Scariot, V.; Peira, G.; Lombardi, G. Foraging Practices and Sustainable Management of Wild Food Resources in Europe: A Systematic Review. Land 2023, 12, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakofjewa, J.; Sartori, M.; Šarka, P.; Kalle, R.; Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R. Boundaries Are Blurred: Wild Food Plant Knowledge Circulation across the Polish-Lithuanian-Belarusian Borderland. Biology 2023, 12, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christenhusz, M.J.M.; Twyford, A.D. The Genome Sequence of the Small Nettle, Urtica urens L. (Urticaceae). Wellcome Open Res. 2024, 9, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcorta, A.; Porta, A.; Tárrega, A.; Alvarez, M.D.; Pilar Vaquero, M. Foods for Plant-Based Diets: Challenges and Innovations. Foods 2021, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a Scale to Measure the Trait of Food Neophobia in Humans. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesías, F.J.; Martín, A.; Hernández, A. Consumers’ Growing Appetite for Natural Foods: Perceptions towards the Use of Natural Preservatives in Fresh Fruit. Food Res. Int. 2021, 150, 110749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujapanda, R.; Hamid; Bashir, O.; Shams, R.; Dash, K.K.; Goksen, G.; Shaikh, A.M.; Béla, K. Influence of Carrier Agents on Nutritional, Chemical, and Antioxidant Profiles of Fruit Juices during Drying Processes: A Comprehensive Review. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, N.; Collier, J.; Neilson, L.; Mellor, C.; Urbanek, E.; Lee, M.; Gatzemeier, J.; Wilkinson, L.L. The Relative Influence of Perceived Processing Level alongside Nutrition, Health, Sustainability and Price on Consumer Decision-Making for Meal-Replacement Products: A Conjoint Analysis. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 133, 105620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embling, R.; Neilson, L.; Mellor, C.; Durodola, M.; Rouse, N.; Haselgrove, A.; Shipley, K.; Tales, A.; Wilkinson, L. Exploring Consumer Beliefs about Novel Fortified Foods: A Focus Group Study with UK-Based Older and Younger Adult Consumers. Appetite 2024, 193, 107139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.; Watkins, L.; Williams, J.; Kean, A. The Positive Role of Labelling on Consumers’ Perceived Behavioural Control and Intention to Purchase Organic Food. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauso, L.; Emrick, S.; de Falco, B.; Lanzotti, V.; Bonanomi, G. Common Dandelion: A Review of Its Botanical, Phytochemical and Pharmacological Profiles. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 1115–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voća, S.; Žlabur, J.Š.; Uher, S.F.; Peša, M.; Opačić, N.; Radman, S. Neglected Potential of Wild Garlic (Allium ursinum L.)—Specialized Metabolites Content and Antioxidant Capacity of Wild Populations in Relation to Location and Plant Phenophase. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant Characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Man | 7 (20.6%) |

| Woman | 25 (73.5%) | |

| Non-binary/third gender | 2 (5.9%) | |

| Ethnicity | White | 27 (79.4%) |

| Asian | 6 (17.6%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Supporting Quotes from Focus Groups |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1. “Why would you want to eat a cactus?” “it’s healthy for you”: Familiarity with consuming nettles | Never heard of eating nettles | “I just thought about it as like, ‘why would you want to eat a cactus?’” |

| Heard of eating nettles but not tried them | “It’s meant to have positive things, but I can’t imagine doing it because to me it’s pain.” | |

| Tried eating nettles | “I think I can remember from when I was a child, so my grandma used to put stinging nettles in soup.” | |

| Theme 2. “Disguise it in your own way” “done and dusted”: Sensory Attributes and Convenience Influences Format. | “You can add it to something and disguise it in your own way.” | |

| Theme 3. “I can’t see why anyone wouldn’t take it” “there are nicer things to drink” It might be healthy but… | … it will not be nice to eat. | “The taste is something that would put me off trying/buying it.” |

| … it is ultra-processed which reduces its healthiness. | “Because you don’t want it to be like a natural supplement and then there’s like highly processed ingredients that, that defeats the point.” | |

| … it is too expensive and difficult to find. | “So if it’s fairly affordable, I’ll use it, I’ll add it to my food, health benefits are good, but if it’s probably over three quid, for the size of not gravy granules, garlic granules you buy, I’d say if it’s over three quid for that, I wouldn’t get it, just because it’s like why would I be buying that when I could go eat kale or something?” | |

| … I do not know how much to consume. | “How much nettle do you need to consume to get all those benefits? […] You know, like is it a dash of powder and suddenly you’re cured, or is it like a whole like five pounds?” | |

| … I do not trust the health claims. | “We’re worried who would be doing it. Who would be making it and for what reasons. If it was a commercial manufacturer who thought wow this is a great idea free, virtually free, nettles and we can sell it as a super super food.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bryant, E.; Walters, D.; Mellor, C.; Neilson, L.; Rouse, N.; Warren-Walker, A.; Lloyd, A.J.; Nash, R.J.; Randall, T.; Wilkinson, L.L. Consumer Perceptions of Botanical Sources of Nutrients: A UK-Based Visual Focus Group Study Exploring Perceptions of Nettles (Urtica dioica) as a Sustainable Food Source. Foods 2025, 14, 3702. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213702

Bryant E, Walters D, Mellor C, Neilson L, Rouse N, Warren-Walker A, Lloyd AJ, Nash RJ, Randall T, Wilkinson LL. Consumer Perceptions of Botanical Sources of Nutrients: A UK-Based Visual Focus Group Study Exploring Perceptions of Nettles (Urtica dioica) as a Sustainable Food Source. Foods. 2025; 14(21):3702. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213702

Chicago/Turabian StyleBryant, Eleanor, Danni Walters, Chloe Mellor, Louise Neilson, Natalie Rouse, Alina Warren-Walker, Amanda J. Lloyd, Robert J. Nash, Tennessee Randall, and Laura L. Wilkinson. 2025. "Consumer Perceptions of Botanical Sources of Nutrients: A UK-Based Visual Focus Group Study Exploring Perceptions of Nettles (Urtica dioica) as a Sustainable Food Source" Foods 14, no. 21: 3702. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213702

APA StyleBryant, E., Walters, D., Mellor, C., Neilson, L., Rouse, N., Warren-Walker, A., Lloyd, A. J., Nash, R. J., Randall, T., & Wilkinson, L. L. (2025). Consumer Perceptions of Botanical Sources of Nutrients: A UK-Based Visual Focus Group Study Exploring Perceptions of Nettles (Urtica dioica) as a Sustainable Food Source. Foods, 14(21), 3702. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213702