Structures, Biological Activities, and Food Industry Applications of Anthocyanins Sourced from Three Berry Plants from the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Brief Introduction of Three Berry Plants from the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau

2.1. Lycium ruthenicum Murr.

2.2. Nitraria tangutorun Bobr

2.3. Rubus idaeus

3. Chemical Structures of Anthocyanins from Three Berry Plants

3.1. Anthocyanins Structures of LRM

3.2. Anthocyanin Structure of NTB

3.3. Anthocyanin Structure of RI

4. Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Pathway

5. Biological Activities of Anthocyanins from Three Berry Plants

5.1. Antioxidant Activity

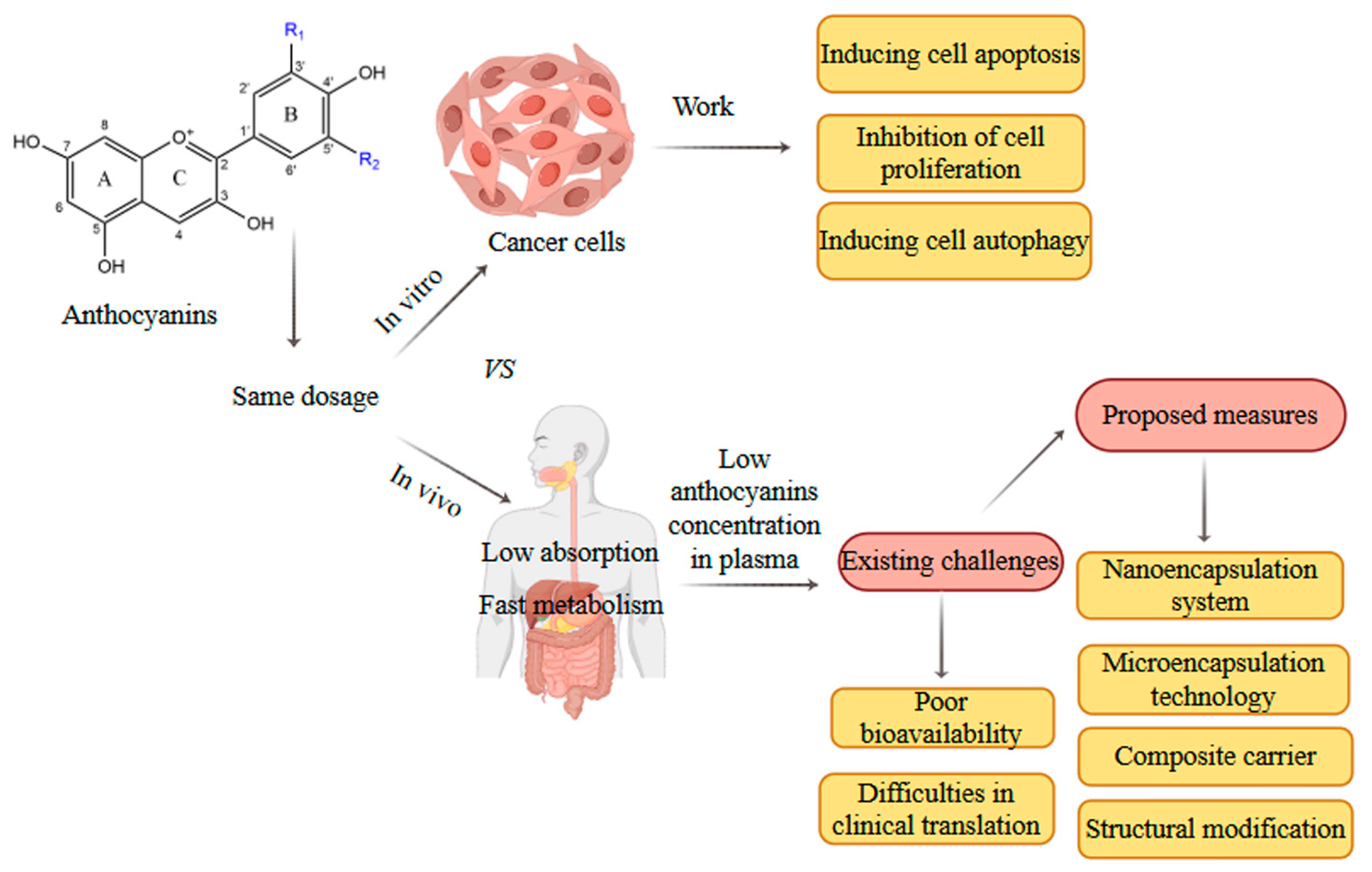

5.2. Anti-Tumor Activity

5.3. Anti-Aging Activity

5.4. Hypoglycemic Activity

5.5. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

5.6. Neuroprotective Activity

5.7. Impacts on Gut Microbiota

5.8. Other Biological Activities

6. Applications in Food Industry

6.1. Natural Colorants

6.2. Packaging Materials and Smart Labels

6.3. Functional Food and Health Supplements

7. Limitations and Future Prospects

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yao, T.; Thompson, L.G.; Mosbrugger, V.; Zhang, F.; Ma, Y.; Luo, T.; Xu, B.; Yang, X.; Joswiak, D.R.; Wang, W. Third pole environment (TPE). Environ. Dev. 2012, 3, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.-p.; Chen, X.-d.; Li, B.-l.; Yao, Y.-h. Biodiversity and conservation in the Tibetan Plateau. J. Geogr. Sci. 2002, 12, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Jia, Q. Integrated Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis of Nitraria Berries Indicate the Role of Flavonoids in Adaptation to High Altitude. Metabolites 2024, 14, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Hao, R.; Fan, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, F. Adaptation of High-Altitude Plants to Plateau Abiotic Stresses: A Case Study of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y. A systematic review on the morphology structure, propagation characteristics, resistance physiology and exploitation and utilization of Nitraria tangutorum Bobrov. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Dong, B.; Liu, C.; Zong, Y.; Shao, Y.; Liu, B.; Yue, H. Variation of anthocyanin content in fruits of wild and cultivated Lycium ruthenicum. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020, 146, 112208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Duan, N.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, N.; Cao, W.; Li, H.; Liu, B.; Tan, F.; Zhao, X. Transcriptome profiling and chlorophyll metabolic pathway analysis reveal the response of Nitraria tangutorum to increased nitrogen. Plants 2023, 12, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tang, X.; Liu, C.; Dong, B.; Shao, Y.; Liu, B.; Yue, H. Ultrasonic extraction of anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murr. and its antioxidant activity. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 2642–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Tao, W.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X.; Yong, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Duan, J.-a. Lycium ruthenicum studies: Molecular biology, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, J.M.; Sáez-Plaza, P.; Ramos-Escudero, F.; Jiménez, A.M.; Fett, R.; Asuero, A.G. Analysis and antioxidant capacity of anthocyanin pigments. Part II: Chemical structure, color, and intake of anthocyanins. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2012, 42, 126–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.W.K.; Solka, M.; Jóźwik, A.; Ksepka, N.; Matin, M.; Wang, D.; Zielińska, A.; Mohanasundaram, A.; Vejux, A.; Zarrouk, A. Anthocyanins-dietary natural products with a variety of bioactivities for the promotion of human and animal health. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep. 2024, 42, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowd, V.; Jia, Z.Q.; Chen, W. Anthocyanins as promising molecules and dietary bioactive components against diabetes A—Review of recent advances. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Giusti, M.M. Anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 620–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.H.; Lin, S.; Wang, Z.Q.; Zong, Y.; Wang, Y. The health-promoting anthocyanin petanin in fruit: A promising natural colorant. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 10484–10497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tena, N.; Martín, J.; Asuero, A.G. State of the art of anthocyanins: Antioxidant activity, sources, bioavailability, and therapeutic effect in human health. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Müller, D.; Richling, E.; Wink, M. Anthocyanin-rich purple wheat prolongs the life span of Caenorhabditis elegans probably by activating the DAF-16/FOXO transcription factor. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 3047–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Les, F.; Cásedas, G.; Gómez, C.; Moliner, C.; Valero, M.S.; López, V. The role of anthocyanins as antidiabetic agents: From molecular mechanisms to in vivo and human studies. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 77, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhi, S. Discovery, development and design of anthocyanins-inspired anticancer agents: A comprehensive review. Anti Cancer Agents Med. Chem. Anti Cancer Agents 2022, 22, 3219–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Khan, M.I.; Shang, X.; Kumar, V.; Kumari, V.; Kesarwani, A.; Ko, E.-Y. Dietary sources, stabilization, health benefits, and industrial application of anthocyanins—A review. Foods 2024, 13, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Hao, F.; Fei, P.; Chen, D.; Fan, H.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, X. Advance on Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Lycium ruthenicum MURR. Pharm. Chem. J. 2022, 56, 844–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Ding, C.; Wang, L.; Li, G.; Shi, J.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Suo, Y. Anthocyanins composition and antioxidant activity of wild Lycium ruthenicum Murr. from Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, J.; Ma, Q.; Li, B.; Li, C.-Q. An approach for extraction, purification, characterization and quantitation of acylated-anthocyanins from Nitraria tangutorun Bobr. fruit. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, H.; Ding, C.; Suo, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, H. Anthocyanins composition and antioxidant activity of two major wild Nitraria tangutorun Bobr. variations from Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2041–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, G.; Liao, X.; Hu, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of anthocyanins in red raspberries and identification of anthocyanins in extract using high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2007, 14, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, M.; Chim, J.F. Nutritional and bioactive value of Rubus berries. Food Biosci. 2019, 31, 100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Q.; Wang, B.; Chen, F.; Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Luo, P.G. Comparison of anthocyanins and phenolics in organically and conventionally grown blueberries in selected cultivars. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.C.; Falcão, A.; Alves, G.; Lopes, J.A.; Silva, L.R. Employ of anthocyanins in nanocarriers for nano delivery: In vitro and in vivo experimental approaches for chronic diseases. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.L.; Escribano-Bailón, M.T.; Alonso, J.J.P.; Rivas-Gonzalo, J.C.; Santos-Buelga, C. Anthocyanin pigments in strawberry. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimerdová, B.; Bobríková, M.; Lhotská, I.; Kaplan, J.; Křenová, A.; Šatínský, D. Evaluation of anthocyanin profiles in various blackcurrant cultivars over a three-year period using a fast HPLC-DAD method. Foods 2021, 10, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbstaite, R.; Raudone, L.; Janulis, V. Phytogenotypic anthocyanin profiles and antioxidant activity variation in fruit samples of the American cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton). Antioxidants 2022, 11, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, S.; Conte, A.; Tagliazucchi, D. Phenolic compounds profile and antioxidant properties of six sweet cherry (Prunus avium) cultivars. Food Res. Int. 2017, 97, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Raghuvanshi, R.; Kumar, R.; Thakur, M.S.; Kumar, S.; Patel, M.K.; Chaurasia, O.; Saxena, S. Current findings and future prospective of high-value trans Himalayan medicinal plant Lycium ruthenicum Murr: A systematic review. Clin. Phytoscience 2022, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.-L.; He, Y.-F.; Xie, L.; Qu, L.-B.; Xu, G.-R.; Cui, C.-X. Research progress on active ingredients and product development of Lycium ruthenicum Murray. Molecules 2024, 29, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Dong, H.; Li, L.; Chen, G. Comparison of different drying pretreatment combined with ultrasonic-assisted enzymolysis extraction of anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murr. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2024, 107, 106933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Xi, J. An efficient approach for the extraction of anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum using semi-continuous liquid phase pulsed electrical discharge system. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 80, 103099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhong, W.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D. Study on anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murr via ultrasonic microwave synergistic extraction and its antioxidant properties. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1052499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Liu, K.; Liang, Y.; Liu, G.; Sang, J.; Li, C. Extraction optimization and purification of anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murr. and evaluation of tyrosinase inhibitory activity of the anthocyanins. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, J.; Dang, K.-k.; Ma, Q.; Li, B.; Huang, Y.-y.; Li, C.-q. Partition Behaviors of Different Polar Anthocyanins in Aqueous Two-Phase Systems and Extraction of Anthocyanins from Nitraria tangutorunBobr. and Lycium ruthenicum Murr. Food Anal. Meth. 2018, 11, 980–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, J.; Ma, Q.; Ren, M.-j.; He, S.-t.; Feng, D.-d.; Yan, X.-l.; Li, C.-q. Extraction and characterization of anthocyanins from Nitraria tangutorunbobr. dry fruit and evaluation of their stability in aqueous solution and taurine-contained beverage. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, J.; Liu, K.; Ma, Q.; Li, B.; Li, C.-q. Combination of a deep eutectic solvent and macroporous resin for green recovery of anthocyanins from Nitraria tangutorunBobr. fruit. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 3082–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Wang, L.; Yin, W.; Liang, J. Antioxidant activity and subcritical water extraction of anthocyanin from raspberry process optimization by response surface methodology. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Tan, J.; Li, Q.; Tang, J.; Cai, X. Optimization ultrasound-assisted deep eutectic solvent extraction of anthocyanins from raspberry using response surface methodology coupled with genetic algorithm. Foods 2020, 9, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhou, X.; Deng, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, C.; Gong, X. Optimization of the microwave-assisted extraction and antioxidant activities of anthocyanins from blackberry using a response surface methodology. Rsc Adv. 2015, 5, 19686–19695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Gao, T.; Yang, H.; Du, Y.; Li, C.; Wei, L.; Zhou, T.; Lu, J.; Bi, H. Simultaneous microwave/ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic extraction of antioxidant ingredients from Nitraria tangutorunBobr. juice by-products. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 66, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Bakar, M.F.; Ismail, N.A.; Isha, A.; Mei Ling, A.L. Phytochemical composition and biological activities of selected wild berries (Rubus moluccanus L., R. fraxinifolius Poir., and R. alpestris Blume). Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 2482930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Nisar, T.; Fang, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Gu, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, W. Current developments on chemical compositions, biosynthesis, color properties and health benefits of black goji anthocyanins: An updated review. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Giusti, M.M. Anthocyanins: Natural colorants with health-promoting properties. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 1, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, J.; Fu, D.; Zhang, X.; Peng, X.; Liang, X. Characterization of anthocyanins in wild Lycium ruthenicum Murray by HPLC-DAD/QTOF-MS/MS. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 4947–4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Aierken, A.; Pang, H.; Du, S.; Feng, M.; Ma, K.; Gao, S.; Bai, G.; Ma, C. Constituent analysis and quality control of anthocyanin constituents of dried Lycium ruthenicum Murray fruits by HPLC–MS and HPLC–DAD. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2016, 39, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, G.; Meng, J.; Deng, K.; Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Hu, N.; Suo, Y. Anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murr. ameliorated d-galactose-induced memory impairment, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation in adult rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 3140–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sang, J.; Li, C.Q. Anthocyanins from Nitraria tangutorun: Qualitative and quantitative analyses, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities and their stabilities as affected by some phenolic acids. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ma, J.; Bi, H.; Song, J.; Yang, H.; Xia, Z.; Du, Y.; Gao, T.; Wei, L. Characterization and cardioprotective activity of anthocyanins from Nitraria tangutorum Bobr. by-products. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2771–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, G.; Dong, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Hu, N. Characterization, antioxidant, and neuroprotective effects of anthocyanins from Nitraria tangutorum Bobr. fruit. Food Chem. 2021, 353, 129435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Zheng, J.; Li, W.; Suo, Y. Isolation, stability, and antioxidant activity of anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murray and Nitraria tangutorum Bobr of Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 2897–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ancos, B.; Gonzalez, E.; Cano, M.P. Differentiation of raspberry varieties according to anthocyanin composition. Z. Für Leb. Und Forsch. A 1999, 208, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jia, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ren, F. Anthocyanin and its Bioavailability, Health Benefits, and Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Food Rev. Int. 2024, 40, 3666–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.; Fang, T.; Lin, Q.; Song, H.; Liu, B.; Chen, L. Red raspberry and its anthocyanins: Bioactivity beyond antioxidant capacity. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2017, 66, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Giusti, M.M.; Stoner, G.D.; Schwartz, S.J. Characterization of a new anthocyanin in black raspberries (Rubus occidentalis) by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2006, 94, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čanadanović-Brunet, J.; Vulić, J.; Ćebović, T.; Ćetković, G.; Čanadanović, V.; Djilas, S.; Šaponjac, V.T. Phenolic profile, antiradical and antitumour evaluation of raspberries pomace extract from Serbia. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2017, 16, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Y.; Sasaki, N.; Ohmiya, A. Biosynthesis of plant pigments: Anthocyanins, betalains and carotenoids. Plant J. 2008, 54, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, M.; Pop, R.; Daescu, A.; Pintea, A.; Socaciu, C.; Rugina, D. Anthocyanins as key phytochemicals acting for the prevention of metabolic diseases: An overview. Molecules 2022, 27, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Putterill, J.; Dare, A.P.; Plunkett, B.J.; Cooney, J.; Peng, Y.; Souleyre, E.J.; Albert, N.W.; Espley, R.V.; Günther, C.S. Two genes, ANS and UFGT2, from Vaccinium spp. are key steps for modulating anthocyanin production. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1082246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, T.; Ge-Zhang, S.; Song, M. Anthocyanins in metabolites of purple corn. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1154535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonekura-Sakakibara, K.; Nakayama, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Saito, K. Modification and stabilization of anthocyanins. In Anthocyanins: Biosynthesis, Functions, and Applications; Spring: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hichri, I.; Barrieu, F.; Bogs, J.; Kappel, C.; Delrot, S.; Lauvergeat, V. Recent advances in the transcriptional regulation of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2465–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuglevand, G.; Jackson, J.A.; Jenkins, G.I. UV-B, UV-A, and blue light signal transduction pathways interact synergistically to regulate chalcone synthase gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1996, 8, 2347–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, Y.J.; Zhang, F.J.; Zhang, G.Z.; Jiang, X.Y.; Yu, H.M.; Hou, B.K. The Arabidopsis UDP-glycosyltransferases UGT79B2 and UGT79B3, contribute to cold, salt and drought stress tolerance via modulating anthocyanin accumulation. Plant J. 2017, 89, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, J.-Y.; Felippes, F.F.; Liu, C.-J.; Weigel, D.; Wang, J.-W. Negative regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis by a miR156-targeted SPL transcription factor. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hu, N.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, G. Bioactivity-guided isolation of the major anthocyanin from Lycium ruthenicum Murr. fruit and its antioxidant activity and neuroprotective effects in vitro and in vivo. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 3247–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yan, Y.; Ran, L.; Mi, J.; Sun, Y.; Lu, L.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, X.; Cao, Y. Isolation, antioxidant property and protective effect on PC12 cell of the main anthocyanin in fruit of Lycium ruthenicum Murray. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 30, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Hu, N.; Ding, C.; Zhang, Q.; Li, W.; Suo, Y.; Wang, H.; Bai, B.; Ding, C. In vitro and in vivo biological activities of anthocyanins from Nitraria tangutorunBobr. fruits. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wan, P.; Dong, W.; Huang, K.; Ran, L.; Mi, J.; Lu, L.; Zeng, X.; Cao, Y. Effects of long-term intake of anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murray on the organism health and gut microbiota in vivo. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Ji, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Wei, T.; Cao, X.; Yang, M.; Bai, C.; Wang, Z. Anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum murray inhibit HepG2 cells growth, metastasis and promote apoptosis and G2/M phase cycle arrest by activating the AMPK/mTOR autophagy pathway. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 9609596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.S.; Wang, X.Y.; Xu, K.; Yang, X.B.; Wang, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.K.; Guo, X.; Sun, J.Y.; Li, L.; et al. Synergistic antitumor effects of polysaccharides and anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murr. on human colorectal carcinoma LoVo cells and the molecular mechanism. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 2956–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, M.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Y.; Pang, W.; Ma, T.; Niu, C.; Yang, Z.; Chang, A.K.; Li, X. Sirtuin1 (SIRT1) is involved in the anticancer effect of black raspberry anthocyanins in colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Feng, R.; Wang, S.Y.; Bowman, L.; Lu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Castranova, V.; Jiang, B.-H.; Shi, X. Cyanidin-3-glucoside, a natural product derived from blackberry, exhibits chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 17359–17368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.W.; Wan, G.M.; Wang, G.; Zhang, M.H.; Li, N.X.; Zhang, Q.N.; Yan, H.L. Anthocyanin from Lycium ruthenicum Murr. in the Qaidam Basin Alleviates Ultraviolet-Induced Apoptosis of Human Skin Fibroblasts by Regulating the Death Receptor Pathway. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 2925–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Wang, Y.-s.; Hwang, E.; Lin, P.; Bae, J.; Seo, S.A.; Yan, Z.; Yi, T.-H. Rubus idaeus L. (red raspberry) blocks UVB-induced MMP production and promotes type I procollagen synthesis via inhibition of MAPK/AP-1, NF-κβ and stimulation of TGF-β/Smad, Nrf2 in normal human dermal fibroblasts. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018, 185, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Hu, N. Long-term dietary Lycium ruthenicum murr. Anthocyanins intake alleviated oxidative stress-mediated aging-related liver injury and abnormal amino acid metabolism. Foods 2022, 11, 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ren, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, N.; Tie, F.; Dong, Q.; Wang, H. Multi-Protective Effects of Petunidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroylrutinoside)-5-O-glucoside on D-Gal-Induced Aging Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, L.; Fang, Z.; Nisar, T.; Zou, L.; Li, D.; Guo, Y. Lycium ruthenicum Murray anthocyanins effectively inhibit α-glucosidase activity and alleviate insulin resistance. Food Biosci. 2021, 41, 100949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Dong, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tan, N.; Wang, H.; Hu, N. Optimization of subcritical water extraction, UPLC–triple–TOF–MS/MS analysis, antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of anthocyanins from Nitraria sibirica Pall. fruits. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, B.; Zhao, J.; Xie, X.; Chen, T.; Yin, Y.; Zhai, R.; Wang, X.; An, W.; Li, J. Anthocyanins from the fruits of Lycium ruthenicum Murray improve high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance by ameliorating inflammation and oxidative stress in mice. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 3855–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Tan, N.; Ouyang, J.; Wang, R.; Tie, F.; Dong, Q.; Wang, H.; Hu, N. Hypoglycaemic activity of the anthocyanin enriched fraction of Lycium ruthenicum Murr. Fruits and its ingredient identification via UPLC–triple-TOF-MS/MS. Food Chem. 2024, 461, 140837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pergola, C.; Rossi, A.; Dugo, P.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Sautebin, L. Inhibition of nitric oxide biosynthesis by anthocyanin fraction of blackberry extract. Nitric Oxide 2006, 15, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanowska, U.; Baraniak, B.; Bogucka-Kocka, A. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and postulated cytotoxic activity of phenolic and anthocyanin-rich fractions from polana raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) fruit and juice—In vitro study. Molecules 2018, 23, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, S.; Zhou, W.; Meng, J.; Deng, K.; Zhou, H.; Hu, N.; Suo, Y. Anthocyanin composition of fruit extracts from Lycium ruthenicum and their protective effect for gouty arthritis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 129, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.J.; Yan, Y.M.; Wan, P.; Chen, D.; Ding, Y.; Ran, L.W.; Mi, J.; Lu, L.; Zhang, Z.J.; Li, X.Y.; et al. Gut microbiota modulation and anti-inflammatory properties of anthocyanins from the fruits of Murray in dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 136, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, T.; Guan, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, S.; Li, M.; Chang, A.K.; Yang, Z.; Bi, X. Black raspberry anthocyanins protect BV2 microglia from LPS-induced inflammation through down-regulating NOX2/TXNIP/NLRP3 signaling. J. Berry Res. 2021, 11, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Johnson, S.L.; Liu, W.; DaSilva, N.A.; Meschwitz, S.; Dain, J.A.; Seeram, N.P. Evaluation of polyphenol anthocyanin-enriched extracts of blackberry, black raspberry, blueberry, cranberry, red raspberry, and strawberry for free radical scavenging, reactive carbonyl species trapping, anti-glycation, anti-β-amyloid aggregation, and microglial neuroprotective effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Peng, Y.; Tang, J.; Mi, J.; Lu, L.; Li, X.; Ran, L.; Zeng, X.; Cao, Y. Effects of anthocyanins from the fruit of Lycium ruthenicum Murray on intestinal microbiota. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 48, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wan, P.; Chen, C.; Chen, D.; Zeng, X.; Cao, Y. Prebiotic effects in vitro of anthocyanins from the fruits of Lycium ruthenicum Murray on gut microbiota compositions of feces from healthy human and patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Lwt 2021, 149, 111829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhou, W.; Xu, W.; Peng, Y.; Yan, Y.; Lu, L.; Mi, J.; Zeng, X.; Cao, Y. The main anthocyanin monomer from Lycium ruthenicum Murray fruit mediates obesity via modulating the gut microbiota and improving the intestinal barrier. Foods 2021, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Xie, L.; Xu, Y.; Ke, H.; Bao, T.; Li, Y.; Chen, W. Pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside derived from wild raspberry exerts antihyperglycemic effect by inducing autophagy and modulating gut microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 68, 13025–13037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhong, W.; Shu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D. Antibacterial effect and mechanism of anthocyanin from Lycium ruthenicum Murr. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 974602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vara, A.L.; Pinela, J.; Dias, M.I.; Petrović, J.; Nogueira, A.; Soković, M.; Ferreira, I.C.; Barros, L. Compositional features of the “Kweli” red raspberry and its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Foods 2020, 9, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauze-Baranowska, M.; Majdan, M.; Hałasa, R.; Głód, D.; Kula, M.; Fecka, I.; Orzeł, A. The antimicrobial activity of fruits from some cultivar varieties of Rubus idaeus and Rubus occidentalis. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 2536–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.J.; Xing, L.J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, R.F.; Li, X.Y.; Dong, J. Anti-fatigue activities of anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murry. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e242703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, Z.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, W.; Huang, X.; Si, M.; Du, X.; Wang, S. Protective effect and mechanism of Lycium ruthenicum Murray anthocyanins against retinal damage induced by blue light exposure. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 5113–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Zhi, Y.; Tian, F.; Huang, F.; Cheng, X.; Wu, A.; Tao, L.; Guo, Z.; Shen, X. Ameliorative effect of black raspberry anthocyanins on diabetes retinopathy by inhibiting axis protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B-endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 107, 105696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Luo, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wang, X.; Ding, M.; Wang, W.; Shen, X.; Zhao, Y. Multiple roles of black raspberry anthocyanins protecting against alcoholic liver disease. Molecules 2021, 26, 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighodaro, O.; Akinloye, O. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alex. J. Med. 2018, 54, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: How are they linked? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1603–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Su, H.; Xu, Y.; Bao, T.; Zheng, X. Protective effect of wild raspberry (Rubus hirsutus Thunb.) extract against acrylamide-induced oxidative damage is potentiated after simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demain, A.L.; Vaishnav, P. Natural products for cancer chemotherapy. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011, 4, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavas, S.; Quazi, S.; Karpiński, T.M. Nanoparticles for cancer therapy: Current progress and challenges. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lou, W.; Wang, J. Advances in nucleic acid therapeutics: Structures, delivery systems, and future perspectives in cancer treatment. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-S.; Stoner, G.D. Anthocyanins and their role in cancer prevention. Cancer Lett. 2008, 269, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.W.; Gong, C.C.; Song, H.F.; Cui, Y.Y. Effects of anthocyanins on the prevention and treatment of cancer. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1226–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashwan, A.K.; Karim, N.; Xu, Y.; Xie, J.; Cui, H.; Mozafari, M.; Chen, W. Potential micro-/nano-encapsulation systems for improving stability and bioavailability of anthocyanins: An updated review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 3362–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G.; del Castillo, M.L.R.; Costabile, A.; Klee, A.; Guergoletto, K.B.; Gibson, G.R. In vitro fermentation of anthocyanins encapsulated with cyclodextrins: Release, metabolism and influence on gut microbiota growth. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 16, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.; Rojanasasithara, T.; Mutilangi, W.; McClements, D.J. Enhanced stability of anthocyanin-based color in model beverage systems through whey protein isolate complexation. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, F. Enhancing the Bioavailability and Stability of Anthocyanins for the Prevention and Treatment of Central Nervous System-Related Diseases. Foods 2025, 14, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Tang, X.; Mao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Tian, F.; Zhao, J.; Cui, S.; Chen, W. Anti-aging effects and mechanisms of anthocyanins and their intestinal microflora metabolites. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2024, 64, 2358–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-D.; Li, J.-J.; Zhang, S.; Chen, D.-X.; Chen, X.; Yin, Z.-C.; Shen, Y.-P.; Gao, J.-Y.; Zhang, J.-K.; Chen, H.-B. Research progress on the regulatory effects of Chinese food and medicine homology on type 1 diabetes mellitus. Food Med. Homol. 2025, 3, 9420085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, R.A.S.; Pastore, G.M. Evaluation of the effects of anthocyanins in type 2 diabetes. Food Res. Int. 2012, 46, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Lee, H.-J. Anti-inflammatory activity of bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.). Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 4570–4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Du, B.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, F. An insight into anti-inflammatory activities and inflammation related diseases of anthocyanins: A review of both in vivo and in vitro investigations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanowska, U.; Baraniak, B. Antioxidant and potentially anti-inflammatory activity of anthocyanin fractions from pomace obtained from enzymatically treated raspberries. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Feng, D.; Yang, D.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Wang, G.; Tian, L.; Jiang, X.; Bai, W. Protective effects of anthocyanins on neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 117, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Xu, J.; Yang, M.; Hussain, M.; Liu, X.; Feng, F.; Guan, R. Protective effect of anthocyanins against neurodegenerative diseases through the microbial-intestinal-brain axis: A critical review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badshah, H.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, M.O. Protective effects of anthocyanins against amyloid beta-induced neurotoxicity in vivo and in vitro. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 80, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, A.; Fernandes, I.; Norberto, S.; Mateus, N.; Calhau, C. Interplay between anthocyanins and gut microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 6898–6902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Tan, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, G.; Sun, J.; Ou, S.; Chen, W.; Bai, W. Metabolism of anthocyanins and consequent effects on the gut microbiota. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, G.C.V.; Goh, J.K.; Choo, W.S. Application of anthocyanins from black goji berry in fermented dairy model food systems: An alternate natural purple color. LWT 2024, 198, 115975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.; Pinela, J.; Abreu, R.M.; Añibarro-Ortega, M.; Pires, T.C.; Saldanha, A.L.; Alves, M.J.; Nogueira, A.; Ferreira, I.C.; Barros, L. Extraction of anthocyanins from red raspberry for natural food colorants development: Processes optimization and in vitro bioactivity. Processes 2020, 8, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patras, A.; Brunton, N.P.; O’Donnell, C.; Tiwari, B.K. Effect of thermal processing on anthocyanin stability in foods; mechanisms and kinetics of degradation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, B.; Gul, K.; Wani, A.A.; Singh, P. Health benefits of anthocyanins and their encapsulation for potential use in food systems: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 2223–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudharsan, M.S.; Mani, H.; Kumar, L.; Pazhamalai, V.; Hari, S. Pectin based colorimetric film for monitoring food freshness. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2023, 11, 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Yun, D.; Xu, F.; Chen, D.; Kan, J.; Liu, J. Smart packaging films based on starch/polyvinyl alcohol and Lycium ruthenicum anthocyanins-loaded nano-complexes: Functionality, stability and application. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 119, 106850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Gao, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, P. Preparation of soybean isolate protein/xanthan gum/agar-Lycium ruthenicum anthocyanins intelligent indicator films and its application in mutton preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Gao, L.; Wang, J.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, M.; Ma, X.; Wang, G.; Lv, S. Preparation and Application of pH-Sensitive Film Containing Anthocyanins Extracted from Lycium ruthenicum Murr. Materials 2023, 16, 3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, C.; Codină, G.G.; Héjja, M.; András, C.D.; Chetrariu, A.; Dabija, A. Study of antioxidant activity of garden blackberries (Rubus fruticosus L.) extracts obtained with different extraction solvents. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Yao, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z. Anthocyanins in Black Wolfberry (Lycium ruthenicum Murray): Chemical Structure, Composition, Stability and Biological Activity. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowska, A.; Dzierżanowski, T. Targeting inflammation by anthocyanins as the novel therapeutic potential for chronic diseases: An update. Molecules 2021, 26, 4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bars-Cortina, D.; Sakhawat, A.; Piñol-Felis, C.; Motilva, M.-J. Chemopreventive effects of anthocyanins on colorectal and breast cancer: A review. In Seminars in Cancer Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, B.; Pandey, R.P.; Darsandhari, S.; Parajuli, P.; Sohng, J.K. Combinatorial approach for improved cyanidin 3-O-glucoside production in Escherichia coli. Microb. Cell Factories 2019, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Ren, J.; Lu, J.; Luo, F. Advances in embedding techniques of anthocyanins: Improving stability, bioactivity and bioavailability. Food Chem. X 2023, 20, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-H.; Stephen Inbaraj, B. Nanoemulsion and nanoliposome based strategies for improving anthocyanin stability and bioavailability. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, H.; Sang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Liao, J.; Tan, J. Research progress on absorption, metabolism, and biological activities of anthocyanins in berries: A review. Antioxidants 2022, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sources | Main Anthocyanin Types | Total Anthocyanins Content (mg C3G/100 g FW) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lycium ruthenicum Murr. | Petunidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl-rutino side)-5-glucoside Pentunidin-3-O-(cis-p-coumaroyl-rutinoside)-5-O-glucoside Petundin-3-O-galactoside-5-O-glucoside Petunidin-3-O-(caffeoyl-rutinoside)-5-O-glucoside | 450–550 | [21] |

| Nitraria tangutorun | Cyanidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-diglucoside Cyanidin-3-O-(cis-p-coumaroyl)-diglucoside Cyanidin-3-O-(caffeoyl)-diglucoside | 8.1–239.86 | [22,23] |

| Raspberry | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside Cyanidin-3-O-sophoroside Cyanidin-3-O-sambubioside Cyanidin-3-O-xylosylrutinoside | 14.7–336 | [24,25] |

| Blueberry | Cyanidin-3-O-galactoside Petunidin-3-O-glucoside Peonidin-3-O-galactoside Delphinidin-3-O-galactoside Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside | 69.97–378.31 | [26,27] |

| Strawberry | Pelargonium-3-O-rutinoside Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside Pelargonium-3-O-glucoside | 29.00–49.43 | [27,28] |

| Blackcurrant Cultivars | Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside Delphinidin 3-O-rutinoside Cyanidin-3-O-utinoside | 62.80–271.33 | [27,29] |

| Cranberry | Cyanidin-3-O-galactoside Cyanidin-3-O-arabinoside Peonidin-3-O-galactoside Peonidin-3-O-arabinoside | 11.10–32.00 | [27,30] |

| Sweet cherry | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside Peonidin-3-O-rutinoside Pelargonidin-3-O-rutinoside | 1.03–179.14 | [27,31] |

| Sources | Extraction Method | Optimal Extraction Condition | Extraction Yield | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lycium ruthenicum Murr. | Semi-continuous liquid phase pulsed electrical discharge system | Solvent composition: 20% ethanol Input voltage: 8 KV Extraction time: 8 min Solid–liquid ratio: 1:2 g/mL | 15.75 ± 0.28 mg/g DW | [35] |

| Ultrasonic microwave synergistic extraction | Solvent composition: 1% HCl-70% ethanol Extraction time: 26.141 min Ultrasonic power: 216.253 W Microwave power: 89.311 W Solid–liquid ratio: 1:17.294 g/mL | 10.157 mg/g DW | [36] | |

| Enzyme-assisted extraction | Solvent composition: 0.1%HCl water-containing pectinase Extraction temperature: 37 min Extraction time: 38 °C Solid–liquid ratio: 1:20 g/mL | 19.51 ± 0.21 mg/g DW | [37] | |

| Ultrasonic extraction | Solvent composition: 90% ethanol Extraction temperature: 40 °C Ultrasonic power: 300 W Extraction time: 30 min Solid–liquid ratio: 1:20 g/mL | 27.66 mg/g DW | [8] | |

| Ultrasonic-assisted enzymolysis extraction | Solvent composition: 0.24% pectinase Extraction temperature: 48 °C Extraction time: 21 min Solid–liquid ratio: 1:21 g/mL | 31.6 mg/g DW | [34] | |

| Nitraria tangutorun | Aqueous two-phase extraction | Solvent composition: 28% NaH2PO4 Extraction temperature: 65 °C Extraction time: 45 min Ultrasonic power: 300 W Solid–liquid ratio: 1:10 g/mL | 3.62 ± 0.05 mg/g DW | [38] |

| Ultrasound-assisted extraction | Solvent composition: 54% ethanol containing 0.1%HCl Extraction temperature: 68 °C Extraction time: 30 min Ultrasonic power: 300 W Solid–liquid ratio: 15 g/mL | 3.862 mg/g DW | [39] | |

| Ultrasound-assisted deep eutectic solvent extraction | Solvent composition: Choline chloride/1,2-propanediol containing 25% water Extraction temperature: 50 °C Extraction time: 30 min Ultrasonic power: 300 W | 1.413 ± 0.054 mg/g DW | [40] | |

| Raspberry | Subcritical water extraction | Solvent composition: superheated water Extraction temperature: 130 °C Flow rate: 3 mL/min Extraction time: 9 min Extraction pressure: 7 MPa | 0.98 ± 0.33 mg/g FW | [41] |

| Ultrasound-assisted deep eutectic solvent extraction | Solvent composition: 1,4-butanediol as the HBD and mole ratio of 1:3 Extraction temperature: 51 °C Extraction time: 32 min Ultrasonic power: 210 W | 1.378 mg/g DW | [42] | |

| Ultrasound-assisted extraction | Solvent composition: 1.5 M HCl–95% ethanol (15:85) Extraction temperature: 51 °C Extraction time: 200 s Ultrasonic power: 400 W Solid–liquid ratio: 1:4 g/mL | 0.345 mg/g FW | [24] | |

| Microwave-assisted extraction | Solvent composition: 52% ethanol Extraction temperature: 55 °C Extraction time: 4 min Microwave power: 469 W Solid–liquid ratio: 1:25 g/mL | 2.18 ± 0.06 mg/g DW | [43] |

| NO. | Compound Name | Position 3 | Position 5 | Analytical Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petunidin | |||||

| 1 | Petundin-3-O-galactoside-5-O-glucoside | Gal | Glu | HPLC-MS | [21] |

| 2 | Petundin-3-O-glucoside-5-O-glucoside | Glu | Glu | HPLC-MS/NMR | [21] |

| 3 | Petunidin-3-O-rutinoside (caffeoyl)-5-O-glucoside | Rut (caffeoyl) | Glu | HPLC-MS | [21] |

| 4 | Pentunidin-3-O-rutinoside (cis-p-coumaroyl)-5-O-glucoside | Rut (cis-p-coumaroyl) | Glu | HPLC-MS/NMR | [21] |

| 5 | Pentunidin-3-O-rutinoside (trans-p-coumaroyl)-5-O-glucoside | Rut (trans-p-coumaroyl) | Glu | HPLC-MS | [21] |

| 6 | Pentunidin-3-O-glucoside (maloyl)-5-O-glucoside | Glu (maloyl) | Glu | HPLC-MS | [21] |

| 7 | Pentunidin-3-O-glucoside (feruloyl)-5-O-glucoside | Glu (feruloyl) | Glu | HPLC-MS | [21] |

| 8 | Petunidin-3-O- rutinoside isomer-(p-coumaroyl) | Rut isomer-(p-coumaroyl) | OH | HPLC-MS | [37] |

| Delphinidin | |||||

| 9 | Delphinidin-3-O-rutinoside (cis-p-coumaroyl)-5-O-glucoside | Rut (cis-p-coumaroyl) | Glu | HPLC-MS | [21] |

| 10 | Delphinidin-3-O-rutinoside (trans-p-coumaroyl)-5-O-glucoside | Rut (trans-p-coumaroyl) | Glu | HPLC-MS | [21] |

| 11 | Delphinidin-3-O-rutinoside-5-O-glucoside | Rut | Glu | HPLC-MS | [37] |

| 12 | Delphinidin-3-O-(p-coumaroyl)-glucoside | (p-coumaroyl)-Glu | OH | HPLC-MS | [37] |

| Malvidin | |||||

| 13 | Malvidin-3-O-rutinoside (cis-p-coumaroyl)-5-O-glucoside | Rut (cis-p-coumaroyl) | Glu | HPLC-MS | [21] |

| 14 | Malvidin-3-O-rutinoside(trans-p-coumaroyl)-5-O-glucoside | Rut (trans-p-coumaroyl) | Glu | HPLC-QTOF-MS/MS | [48] |

| 15 | Malvidin-3-O-rutinoside(feruloyl)-5-O-glucoside | Rut (feruloyl) | Glu | HPLC-QTOF-MS/MS | [48] |

| 16 | Malvidin-3-O-rutinoside-5-O-glucoside | Rut | Glu | HPLC- QTOF-MS/MS | [48] |

| Pelargonidin | |||||

| 17 | Pelargonidin-3-O-galactoside | Gal | OH | HPLC-MS | [49] |

| 18 | Pelargonidin-3-O-diglucoside | Di-Glu | OH | HPLC-MS | [49] |

| 19 | Pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside | Glu | OH | HPLC-MS | [49] |

| Cyanidin | |||||

| 20 | Cyanidin-3-O-galactoside | Gal | OH | UPLC- TOF/MS | [50] |

| 21 | Cyanidin-3,5-O-diglucoside | Di-Glu | Di-Glu | UPLC- TOF/MS | [50] |

| 22 | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside | Glu | OH | UPLC- TOF/MS | [50] |

| NO. | Compound Name | Position 3 | Position 5 | Analytical Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyanidin | |||||

| 1 | Cyanidin-3-O-diglucoside-isomer | Di-Glu-isomer | OH | UPLC-MS | [51] |

| 2 | Cyanidin-3-O-hexose | hexose | OH | UPLC-MS | [51] |

| 3 | Cyanidin-3-O-(feruloyl)-diglucoside | (feruloyl)-Di-Glu | OH | UPLC-MS | [51] |

| 4 | Cyanidin-3-O-(cis-p-coumaroyl)-diglucoside | (cis-p-coumaroyl)- Di-Glu | OH | UPLC-MS | [51] |

| 5 | Cyanidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-diglucoside | (trans-p-coumaroyl)-Di-Glu | OH | UPLC-MS/NMR | [51] |

| 6 | Cyanidin-3-O-(p-coumaroyl)-glucoside | (p-coumaroyl)-Glu | OH | UPLC-MS | [51] |

| 7 | Cyanidin-3-O-diglucoside | Di-Glu | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [52] |

| 8 | Cyanidin-3-O-sambubioside | sambubioside | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [52] |

| 9 | Cyanidin-3-O-(cis-caffeoyl)- diglucoside | (cis-caffeoyl)-Di-Glu | OH | UPLC- TOF-MS | [53] |

| 10 | Cyanidin-3-O-(trans-caffeoyl)- diglucoside | (trans-caffeoyl)-Di-Glu | OH | UPLC-TOF-MS | [53] |

| Malvidin | |||||

| 11 | Malvidin-3-O-glucoside | Glu | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [52] |

| 12 | Malvidin-3-O-(acetyl)-glucoside | (acetyl)-Glu | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [52] |

| 13 | Malvidin-3-O-(coumaroyl)-glucoside-5-O-glucoside | (coumaroyl)-Glu | Glu | HPLC-ESI-MS | [52] |

| 14 | Malvidin-3-O-(cis-coumaroyl)-glucoside | (cis-coumaroyl)-Glu | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [52] |

| 15 | Malvidin-3-O-(trans-coumaroyl)-glucoside | (trans-coumaroyl)-Glu | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [52] |

| Peonidin | |||||

| 16 | Peonidin-3-O-diglucoside | Di-Glu | OH | UPLC-MS | [51] |

| 17 | Peonidin-3-O-(coumaroyl)-glucoside-5-O-glucoside | (coumaroyl)-Glu | Glu | HPLC-ESI-MS | [52] |

| 18 | Peonidin-3-O-(coumaroyl)-glucoside | (coumaroyl)-Glu | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [52] |

| Pelargonidin | |||||

| 19 | Pelargonidin-3-O-diglucoside-isomer | Di-Glu-isomer | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [52] |

| 20 | Pelargonidin-3-O-(caffeoyl)-diglucoside | (caffeoyl)-Di-Glu | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [52] |

| 21 | Pelargonidin-3-O-(coumaroyl)-diglucoside | (coumaroyl)-Di-Glu | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS/NMR | [52,54] |

| 22 | Pelargonidin-3-O(ferulyl)- diglucoside | (ferulyl)-Di-Glu | OH | UPLC-TOF-MS | [53] |

| Delphinidin | |||||

| 23 | Delphinidin-3-O-(cis-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside-5-O-glucoside | (cis-p-coumaroyl)-Glu | Glu | UPLC-MS | [51] |

| 24 | Delphinidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside-5-O-glucoside | (trans-p-coumaroyl)-Glu | Glu | UPLC-MS | [51] |

| 25 | Delphinidin-3-O-(coumaroyl)-glucoside | (coumaroyl)-Glu | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [52] |

| NO. | Compound Name | Position 3 | Position 5 | Analytical Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyanidin | |||||

| 1 | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside | Glu | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [58] |

| 2 | Cyanidin-3-O-sambubioside | sambubioside | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [58] |

| 3 | Cyanidin-3-O-xylosylrutinoside | xylosylrutinoside | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [58] |

| 4 | Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside | Rut | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS/NMR | [58] |

| 5 | Cyanidin-3-O-sophoroside | sophoroside | OH | HPLC | [59] |

| 6 | Cyanidin-3-O- (2G-glucosyl-rutinoside) | Glucosyl- Rut | OH | HPLC | [59] |

| Pelargonidin | |||||

| 7 | Pelargonidin-3-O-rutinoside | Rut | OH | HPLC-ESI-MS | [58] |

| 8 | Pelargonidin-3-O-sophoroside | sophoroside | OH | HPLC | [59] |

| 9 | Pelargonidin-3-(2G-glucosyl-rutinoside) | Gucosyl-Rut | OH | HPLC | [59] |

| 10 | Pelargonidin-3-glucoside | Glu | OH | HPLC | [59] |

| Benefits | Treatment | Evaluation Items | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant activity | In vitro studies | ||

| Petunidin monomer from LRM (10 μM) on CML-induced oxidative stress in Neuro-2a cells | ↓ROS, ↓MDA, ↑GSH | [69] | |

| LRA extracts | ↓DPPH, ↓·OH, ↓ABTS, ↓O2•− and ↓ FRAP radicals | [36] | |

| Petunidin monomer from LRM (1–10 μM) on H2O2-induced neuron-like cells | ↑CAT, ↑SOD, ↑GSH-Px, ↓MDA | [70] | |

| RA extracts (containing 6 anthocyanins) | Rate of DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging was 83.77% and 66.66% | [41] | |

| In vivo studies | |||

| Cyanidin monomer from NTB (50 mg/kg) was administrated once daily to D-galactose-induced rats for 7 weeks | ↓ROS, ↓MDA, ↑T-SOD, ↑GSH | [53] | |

| The NTA extracts (0.35, 1.05 and 2.10 g/kg) for 4 weeks on hyperlipemia rats | ↑TAC, ↑SOD, ↓MDA | [71] | |

| LRA extracts (200 mg/kg/d) on C57BL/6 mice for 12 weeks | ↑T-AOC, ↑T-SOD, ↑CAT, ↑GSH, ↑GSH-Px, ↓AST, ↓ALT, ↓ALP and MDA↓ | [72] | |

| Anti-tumor activity | In vitro studies | ||

| Treatment of HepG2 cells with 500 and 1000 μg/mL LRA extracts for 24 h | ↓Cell viability and proliferation, ↓migration and invasion, ↑AMPK/mTOR, ↓G2/M phase, ↑Beclin-1, p62 and LC3-II/LC3-I | [73] | |

| Combined treatment with LRA extracts (20 μg/mL) and polysaccharide extracts from LRM on LoVo cells for 24 h | ↓Cell activity, ↓G0-G1 phase, ↑apoptosis, ↑PI3K-Akt, ↑p-JAK2 and p-STAT3, ↑Caspase-3, ↑Bax/Bcl-2, ↑ROS | [74] | |

| Applying RA extracts to AOM-induced colorectal cancer mice (4.1 g/kg) for 45 days and the CRC cell lines SW480 and Caco-2 cell (0, 25, 50 μg/mL) | ↓Sirtuin1, ↑MOF and EP300, ↑acetylated-p65, ↑NF-κB, ↑Bax, ↓Bcl-2, ↓cyclin-D1, ↓cellular myelocytomatosis oncogene, ↓NLRP3 | [75] | |

| Cyanidin-3-glucoside monomer from RAs on TPA-induced JB6 cells (10, 20, 40 μM) | ↓MAPK, ↓transactivation of NF-κB and AP-1, ↓COX-2, ↓TNFα, ↓AP-1, | [76] | |

| Anti-aging activity | In vitro studies | ||

| LRA extracts (0.1, 0.5, 1.0 mg/mL) against UVB-induced human skin fibroblast cells | ↓Apoptosis rate of HSFs, ↓TNF-α, ↓caspase-7, ↑survivin | [77] | |

| RA extracts against UVB-induced NHDFs cell (1, 10, 100 μg/mL) | ↓MMP, ↓MAPK, ↓NF-κβ, ↓IL-1β ↓AP-1, ↑Nrf2, ↑TGF-β/Smad | [78] | |

| In vivo studies | |||

| LRA extracts on D-galactose-induced aging rats (100 mg/kg/d, 8 weeks) | ↓AGEs, ↓MDA, ↑metallothionein, ↓GSH, ↑GSH-Px, ↑CAT, ↑T-SOD, ↓ TNF-α, ↓IL-6, ↑IL-10 | [79] | |

| Petunidin monomer from LRMs on D-galactose-induced aging mice (50, 100 mg/kg, 8 weeks) | ↑SOD, ↑GSH, ↓MDA, ↓AChE, ↓Iba1, ↓GFAP, ↓BACE-1, ↓Aβ (1–42) | [80] | |

| Hypoglycemic activity | In vitro studies | ||

| LRA extracts on Caco-2 cells (0, 5, 10, 20,40, 80 μg/mL) and IR-HepG2 (25 μg/mL) | IC50 value of α-glucosidase was 25.3 μg/mL, ↑glucose consumption and uptake, ↑PI3K/Akt, ↑GSK3β, ↑FOXO1, ↓ROS | [81] | |

| NTA extracts (containing 8 anthocyanins) | IC50 value of α-glucosidase was 0.1807 ± 0.0135 mg/mL | [82] | |

| In vivo studies | |||

| LRA extracts (50, 100, 200 mg/kg/d for 12 weeks) against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance in mice | ↓AUC, ↓HOMA-IR, ↓fasting insulin, ↓GHb, ↑IRS-1/AKT, ↑Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1, ↓TLR4/NF-κB/JNK | [83] | |

| LRA extracts (containing 10 anthocyanins) on α-glucosidase in vivo (200 and 400 mg/kg) | IC50 value of α-glucosidase was 4.468 mg/mL, ↓AUC, ↓PBG | [84] | |

| Anti-inflammatory activity | In vitro studies | ||

| RA extracts on J774 cells (0, 11, 22, 45 and 90 μg/mL) by LPS stimulation | ↓NO, ↓iNOS, ↓NF-κB, ↓ERK-1/2 | [85] | |

| RA extracts | IC50 value of LOX was 4.85 mg FW/mL, IC50 value of COX-2 was 2.25 mg FW/mL | [86] | |

| In vivo studies | |||

| LRA extracts (200 mg/kg) and petunidin-3-glu (40 mg/kg) against gouty arthritis induced by monosodium urate | TNF-α, ↓IL-1β, ↓IL-18, ↓PE2, ↓COX-1, ↓paw COX-1 mRNA | [87] | |

| LRA extracts (200 mg/kg/d) and the main monomer (P3G) against DSS-induced colitis in mice | ↑body weight, ↑solid fecal weight, ↑colon length, ↓DAI, ↓TNF-α, ↓IL-6, ↓IL-1β, ↓IFN-γ,↑ZO-1, ↑occludin, ↑claudin-1 | [88] | |

| Neuroprotective activity | In vitro studies | ||

| RA extracts against LPS-induced BV2 microglia (3, 10, 30, 100 μg/mL) | ↓iNOS, ↓ROS, ↓gp91 phox, ↓NLRP3, ↓caspase-1, ↓TXNIP, ↑TRX | [89] | |

| RA extracts (20 μg/mL) on BV-2 Microglia | ↓Aβ Fibrillation, ↓NOS, ↓ROS, ↓Caspase-3/7, ↓AGEs | [90] | |

| In vivo studies | |||

| LRA extracts on D-galactose-treated rats (50, 100, 200mg/kg for 7 weeks) | ↓p-JNK, ↓caspase-3, ↓Bax/Bcl2, ↓ memory impairment, ↓RAGE | [50] | |

| NTA extracts on D-galactose-treated rats (50, 100mg/kg for 7 weeks) | ↑learning and memory, ↓RAGE,↓GFAP, ↓Iba-1, ↓ROS, ↓Aβ, ↓gliosis in the hippocampus | [53] | |

| Impacts on gut microbiota | In vitro studies | ||

| Effect on human intestinal microbiota of LRA extracts in vitro | ↓Firmicutes, ↓Bacteroidetes, ↑Actinobacteria,↑Bifidibacterium, ↓ Allisonella,↓Prevotella, ↓Dialister, ↓Megamonas, ↓Clostridium, ↑Allisonella, ↑Sutterellaceae, ↑Blautia, ↓Phascolarctobacterium, ↓Lachnospiraceae, ↓Faecalibacterium | [91] | |

| Effect of LRA extracts and the main monomer on gut microbiota of feces from patients with inflammatory bowel disease | ↑Lactobacillus, ↑Bifidibacteria, ↓Escherichia/Shigella, ↓SCFA, ↑Prevotella | [92] | |

| In vivo studies | |||

| The main LRA monomer on the HFD-induced obesity mice (100 mg/kg) | ↓LPS, ↑Claudin, ↑ZO-1, ↓IL-6, ↓IL-1β, ↓Firmicutes, ↓Lactobacillaceae, ↓Streptococcaceae, ↓Ruminococcaceae, ↓Erysipelotrichaceae, ↑Bifidobacteriaceae, ↑Helicobacteraceae, ↑Deferribacteraceae | [93] | |

| Intake of LRA extracts of mice (200 mg/kg/d for 12 weeks) | ↑ZO-1, ↑occludin, ↑claudin-1, ↑muc1, ↑Barnesiella, ↑Alistipes, ↑Eisenbergiella, ↑Coprobacter, ↑Odoribacter, ↑SCFA | [72] | |

| Pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside anthocyanin monomer from raspberry on db/db diabetic mice (150 mg/kg) | ↑occludin, ↑ZO-1, ↑Tlr2, ↑Pla2g2, ↑Lyz1, ↑Prevotella | [94] | |

| Other bioactivities | In vitro studies | ||

| LRA extracts | The MIC of S. aureus was 3.125 mg/mL, the number of S. aureus colonies was 4.88-log10 CFU/mL, the extracellular K+ concentration of S. aureus was 0.88 mmol/L, ↓intracellular protein of staphylococcus aureus | [95] | |

| RA extracts | The value of MIC of the Bacillus cereus, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella typhimurium was 0.78, 3.12, 3.12, and 3.12mg/mL, respectively. | [96] | |

| RA extracts | S. pneumoniae (MBC 8.0 mg/mL) and C. diphtheriae (MBC 0.5 mg/mL), M. catarrhalis (MBC 0.015 mg/mL), H. pylori (MIC 8 mg/mL), Neisseria meningitidis (MIC 0.06 mg/mL). | [97] | |

| In vivo studies | |||

| LRA extracts on mouse fatigue model (100, 400, 900 mg/kg) | ↑Glu, ↑SOD, ↓LDH, ↓MDA, ↓BUN | [98] | |

| LRA extracts on retinal damage induced by blue light exposure mice (50, 200 mg/kg) | ↑CAT, ↑SOD, ↑GSH-Px, ↓ROS, ↓MDA, ↑Nrf2, ↑HO-1, ↑NQO1, ↓IL-6, ↓L-1β, ↓TNF-α, ↓VEGF-A, ↓p-IκBα/IκBα, ↓Caspase-3/Bax, ↑retina, ↑PSL, ↑INL, ↑ONL | [99] | |

| RA extracts on STZ-induced diabetes rats (35, 140 mg/kg for 6 weeks) | Improved the disorder and disarrangement in INL and ONL, ↓GRP78, ↓RPEC apoptosis, ↓PTP1B, ↓Caspase-1 | [100] | |

| RA extracts on alcohol-induced hepatic injury mice (25, 50, 100 mg/kg) | ↓ALT, ↓AST, ↓CHO, ↓LDL, ↓TBIL, ↓NF-κB, ↓TGF-β | [101] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, Y.; Ren, L.; Zhang, S.; Xie, Y.; Wang, H.; Hu, N. Structures, Biological Activities, and Food Industry Applications of Anthocyanins Sourced from Three Berry Plants from the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Foods 2025, 14, 3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213660

Luo Y, Ren L, Zhang S, Xie Y, Wang H, Hu N. Structures, Biological Activities, and Food Industry Applications of Anthocyanins Sourced from Three Berry Plants from the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Foods. 2025; 14(21):3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213660

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Yaping, Lichengcheng Ren, Shizheng Zhang, Yongjing Xie, Honglun Wang, and Na Hu. 2025. "Structures, Biological Activities, and Food Industry Applications of Anthocyanins Sourced from Three Berry Plants from the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau" Foods 14, no. 21: 3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213660

APA StyleLuo, Y., Ren, L., Zhang, S., Xie, Y., Wang, H., & Hu, N. (2025). Structures, Biological Activities, and Food Industry Applications of Anthocyanins Sourced from Three Berry Plants from the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Foods, 14(21), 3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213660