Upcycled vs. Sustainable: Identifying Consumer Segments and Recognition of Sustainable and Upcycled Foods Within the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

2.1.1. Demographics

2.1.2. Food and Basic Lifestyle

2.1.3. Food Neophobia and Food Technology Neophobia Scales

2.1.4. Diet and Food Purchasing Factors

2.1.5. Influence of Beliefs on Consumption

2.1.6. Awareness and Familiarity

2.1.7. Product Recognition and Role of Information

2.1.8. Cost and Hesitation

2.2. Analysis

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Cluster Segmentation

2.2.3. Segment Comparison

2.3. Ethics Statement

3. Results

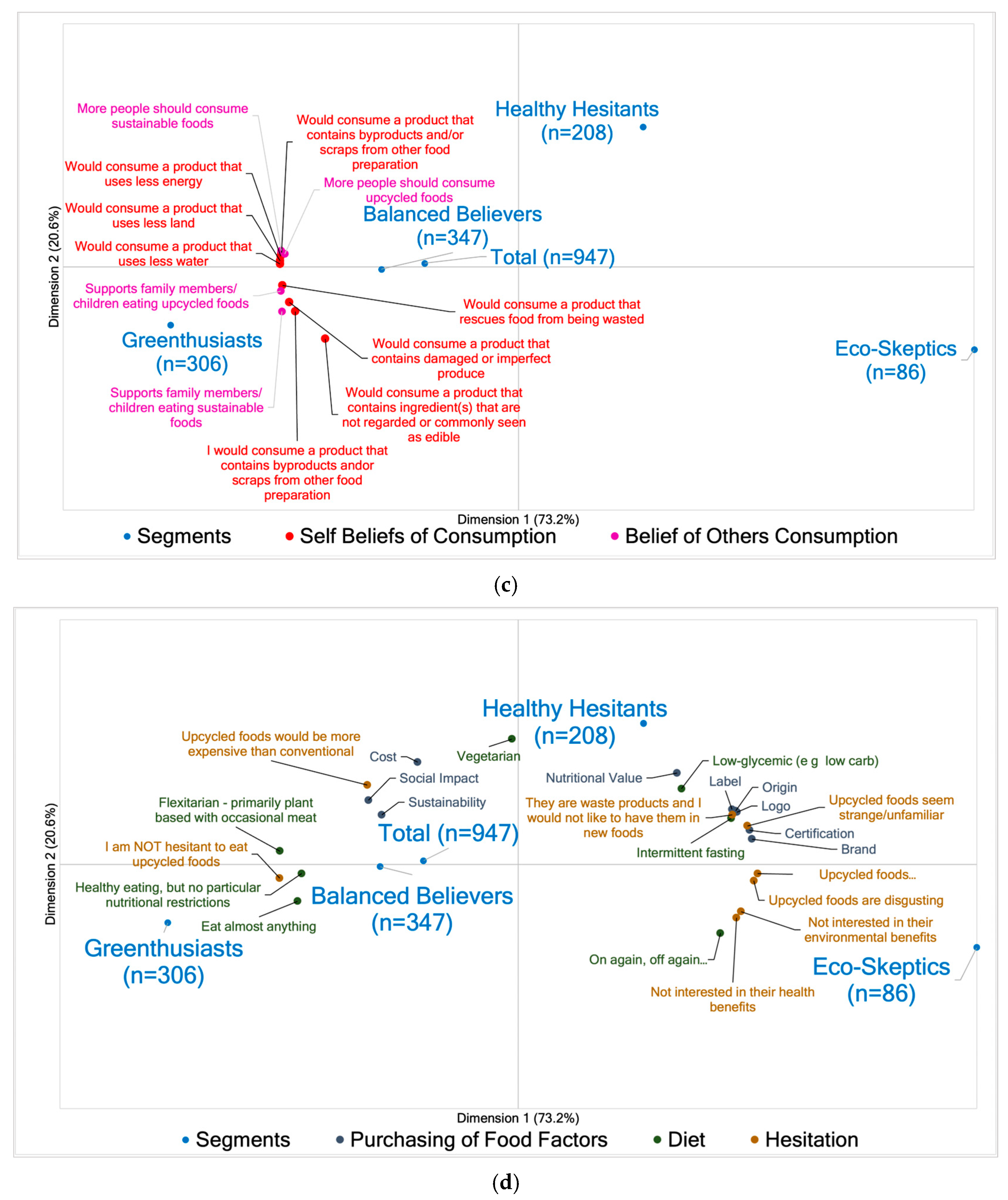

3.1. Cluster Segmentation

- Cluster 1 (n = 306) = Greenthusiasts;

- Cluster 2 (n = 347) = Balanced Believers;

- Cluster 3 (n = 208) = Healthy Hesitants;

- Cluster 4 (n = 86) = Eco-Skeptics.

3.2. Segment Comparison

3.2.1. Demographics

3.2.2. Awareness and Familiarity

3.2.3. Product Recognition and Role of Information

3.2.4. Cost

4. Discussion

4.1. Cluster Segmentation

4.2. Segment Comparison

4.2.1. Demographics

4.2.2. Diet and Purchasing of Food Factors

4.2.3. Awareness and Familiarity

4.2.4. Product Recognition and Role of Information

4.2.5. Cost and Hesitation

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| U.S. | United States |

| FNS | Food Neophobia Scale |

| FTNS | Food Technology Neophobia Scale |

| CATA | Check-all-that-apply |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

Appendix A

| FLA and BLA Statements | Average n = 947 | Greenthusiasts n = 306 | Balanced Believers n = 347 | Healthy Hesitants n = 208 | Eco-Skeptics n = 86 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLA: I am willing to pay more for all natural or organic foods | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| FLA: I am concerned about the environmental impact of the foods I eat | 3.7 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.2 |

| FLA: It’s difficult for me to understand what products are truly nutritious and/or healthy for me and my family | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.2 |

| FLA: I am willing to modify my diet in order to be healthier | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 3.9 |

| FLA: I am concerned about the food I consume going to waste | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 |

| FLA: I am always looking for new foods to help me live a healthier life | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.6 |

| FLA: I and/or other members of my household have food allergies that prevent us from eating certain foods | 2.1 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 3.0 |

| FLA: I believe organic food is more sustainable | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.4 |

| FLA: I am able to trust the food industry | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.2 |

| FLA: I think about examples and benefits of food products | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| FLA: I crave sweet foods | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.9 |

| FLA: I use food as a reward | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.3 |

| FLA: I buy new types of food earlier than other people | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.9 |

| BLA: I am loyal to brands that I like | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| BLA: I exercise regularly | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| BLA: I am able to trust most strangers | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.8 |

| BLA: It is important that others like the products and brands I buy | 2.1 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.9 |

| BLA: Sometimes I buy a product because my friends do so | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| BLA: Name-brand purchase is a good way to distinguish people from others | 2.1 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 3.0 |

| BLA: Name products and brands purchased can bring me a sense of prestige | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.0 |

| BLA: I purchase certain products because it is morally the right thing | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.1 |

| BLA: I often try to avoid products that are bought by the general population | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.8 |

| BLA: I would never throw away things that are still useful | 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.6 |

| BLA: I only buy what I need | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.6 |

| BLA: If I can re-use an item I already have, there’s no sense in buying something new | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 3.8 |

| FNS and FTNS | Average n = 947 | Greenthusiasts n = 306 | Balanced Believers n = 347 | Healthy Hesitants n = 208 | Eco-Skeptics n = 86 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FNS: I am constantly sampling new and different foods | 5.0 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 4.3 |

| FNS: I don’t trust new foods | 2.8 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 4.2 |

| FNS: If I don’t know what is in a food, I won’t try it | 3.7 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 4.9 |

| FNS: I like foods from different countries | 6.0 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 4.5 |

| FNS: Ethnic food looks too weird to eat | 2.0 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 4.1 |

| FNS: At dinner parties, I will try a new food | 5.8 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 4.6 |

| FNS: I am afraid to eat things I have never had before | 2.7 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 4.4 |

| FNS: I am very particular about the foods I will eat | 3.4 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 4.6 | 4.9 |

| FNS: I will eat almost anything | 4.7 | 5.6 | 4.7 | 3.6 | 3.9 |

| FNS: I like to try new ethnic restaurants | 5.7 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 5.0 | 3.9 |

| FTNS: There are plenty of tasty foods around so we don’t need to use new food technologies to produce more | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 4.6 |

| FTNS: The benefits of new food technologies are often grossly overstated | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 4.4 |

| FTNS: New food technologies decrease the natural quality of food | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 4.3 | 4.4 |

| FTNS: There is no sense trying out high-tech food products because the ones I eat are already good enough | 3.3 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 4.3 |

| FTNS: New foods are not healthier than traditional foods | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 4.1 |

| FTNS: New food technologies are something I am uncertain about | 4.2 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 4.6 |

| FTNS: Society should not depend heavily on technologies to solve its food problems | 3.6 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 4.5 |

| FTNS: New food technologies may have long term negative environmental effects | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| FTNS: It can be risky to switch to new food technologies too quickly | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 4.7 |

| FTNS: New food technologies are unlikely to have long term negative health effects | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.9 |

| FTNS: New products produced using new food technologies can help people have a balanced diet | 4.7 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 4.4 |

| FTNS: New food technologies give people more control over their food choices | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 4.5 |

| FTNS: The media usually provides a balanced and unbiased view of new food technologies | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.7 |

| SBC and BOC Statements | Average n = 947 | Greenthusiasts n = 306 | Balanced Believers n = 347 | Healthy Hesitants n = 208 | Eco-Skeptics n = 86 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBC: I would consume a plant-based product | 4.4 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 3.4 |

| SBC: I would consume a product that uses less water to be produced | 4.3 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.4 |

| SBC: I would consume a product that uses less energy to be produced | 4.3 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 3.5 |

| SBC: I would consume a product that uses less land to be produced | 4.3 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 3.4 |

| SBC: I would consume a product that rescues food from being wasted | 4.1 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 3.3 |

| SBC: I would consume a product that contains ingredient(s) that are not regarded or commonly seen as edible | 2.8 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| SBC: I would consume a product that contains damaged or imperfect produce | 3.8 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 2.9 |

| SBC: I would consume a product that contains byproducts and/or scraps from other food preparation | 3.5 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| BOC: I would support my family members or children eating sustainable foods | 4.5 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 3.7 |

| BOC: I think more people should consume sustainable foods | 4.3 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 3.5 |

| BOC: I think more people should consume upcycled foods | 3.9 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| BOC: I would support my family members or children eating upcycled foods | 4.2 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 3.3 |

| Dietary Restrictions | Average n = 947 | Greenthusiasts n = 306 | Balanced Believers n = 347 | Healthy Hesitants n = 208 | Eco-Skeptics n = 86 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eat almost anything | 56.1 | 70.3 | 53.3 | 45.7 | 41.9 |

| Healthy eating, but no particular nutritional restrictions | 57.6 | 58.5 | 59.9 | 54.3 | 52.3 |

| On again, off again healthy eating | 35.6 | 34.3 | 35.4 | 34.6 | 43.0 |

| Flexitarian—primarily plant based with occasional meat | 10.6 | 13.7 | 10.7 | 8.7 | 3.5 |

| Clean—try to eat gluten free, soy-free, and organic when possible | 6.5 | 5.2 | 7.8 | 5.3 | 9.3 |

| Ketogenic | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| Paleo | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| Whole 30/Anti-inflammatory | 3.8 | 2.6 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 9.3 |

| Pescatarian—primarily vegetarian, eats fish and seafood | 5.3 | 4.2 | 6.3 | 5.3 | 4.7 |

| Vegetarian | 9.7 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 14.4 | 7.0 |

| Vegan (no animal products) | 2.6 | 1.3 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 2.3 |

| Gluten-free | 4.6 | 2.3 | 6.9 | 3.8 | 5.8 |

| Dairy-free | 5.6 | 3.9 | 7.8 | 4.3 | 5.8 |

| Intermittent fasting | 13.4 | 11.4 | 13.8 | 14.9 | 15.1 |

| Low-glycemic (e.g. low carb) | 6.5 | 5.6 | 4.9 | 10.1 | 8.1 |

| Other | 3.5 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 3.5 |

| Purchasing of Food Factors | Average n = 947 | Greenthusiasts n = 306 | Balanced Believers n = 347 | Healthy Hesitants n = 208 | Eco-Skeptics n = 86 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | 4.47 | 4.55 | 4.49 | 4.42 | 4.20 |

| Convenience | 4.01 | 3.95 | 4.03 | 4.05 | 4.01 |

| Nutritional Value | 4.44 | 4.49 | 4.46 | 4.42 | 4.24 |

| Upcycled Content | 2.91 | 2.99 | 2.87 | 2.89 | 2.83 |

| Origin | 3.34 | 3.24 | 3.30 | 3.51 | 3.43 |

| Brand | 2.78 | 2.36 | 2.81 | 3.10 | 3.34 |

| Label | 2.90 | 2.50 | 2.95 | 3.26 | 3.24 |

| Logo | 2.13 | 1.77 | 2.14 | 2.47 | 2.50 |

| Certification | 3.29 | 3.01 | 3.28 | 3.59 | 3.63 |

| Taste | 4.77 | 4.81 | 4.78 | 4.75 | 4.62 |

| Quality | 4.63 | 4.59 | 4.65 | 4.67 | 4.58 |

| Product Category | 3.41 | 3.29 | 3.47 | 3.48 | 3.48 |

| Locality | 3.52 | 3.55 | 3.51 | 3.51 | 3.43 |

| Sustainability | 3.58 | 3.78 | 3.48 | 3.59 | 3.28 |

| Social Impact | 2.97 | 3.14 | 2.86 | 3.02 | 2.67 |

| Traceability | 3.10 | 3.01 | 3.12 | 3.16 | 3.17 |

| Hesitation to Purchase or Consume Upcycled Food | Average n = 947 | Greenthusiasts n = 306 | Balanced Believers n = 347 | Healthy Hesitants n = 208 | Eco-Skeptics n = 86 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I think that upcycled foods are disgusting | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 4.8 | 10.5 |

| I have a feeling that upcycled foods would not taste good | 23.1 | 11.1 | 19.6 | 33.7 | 54.7 |

| I think that upcycled foods seem strange/unfamiliar | 20.1 | 7.5 | 17.6 | 35.1 | 38.4 |

| I think that upcycled foods would be more expensive than conventional foods | 46.7 | 45.8 | 48.1 | 47.1 | 43.0 |

| They are waste products and I would not like to have them in new foods | 6.3 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 15.9 | 15.1 |

| I am not interested in their health benefits | 2.4 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 10.5 |

| I am not interested in their environmental benefits | 2.7 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 3.4 | 14.0 |

| I am NOT hesitant to eat upcycled foods | 51.2 | 68.6 | 55.0 | 33.2 | 17.4 |

| Other | 4.2 | 4.6 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 8.1 |

References

- McKenzie, F.C.; Williams, J. Sustainable Food Production: Constraints, Challenges and Choices by 2050. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2024; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024; Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/45230 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Richards, J.; Lammert, A.; Madden, J.; Cahn, A.; Kang, I.; Amin, S. Addition of Carrot Pomace to Enhance the Physical, Sensory, and Functional Properties of Beef Patties. Foods 2024, 13, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Upcycled Foods Definition Task Force. Defining Upcycled Foods; Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation. 2020. Available online: https://chlpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Upcycled-Food_Definition.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- Lu, P.; Parrella, J.A.; Xu, Z.; Kogut, A. A Scoping Review of the Literature Examining Consumer Acceptance of Upcycled Foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 114, 105098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, E.; Kahveci, D. Consumers’ Purchase Intention for Upcycled Foods: Insights from Turkey. Future Foods 2022, 6, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Asioli, D.; Banovic, M.; Perito, M.A.; Peschel, A.O. Communicating Upcycled Foods: Frugality Framing Supports Acceptance of Sustainable Product Innovations. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 100, 104596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, S.; Asioli, D. Consumer Preferences for Upcycled Ingredients: A Case Study with Biscuits. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 84, 103951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, B.; Kapetanaki, A.B.; Wang, P. Completing the Food Waste Management Loop: Is There Market Potential for Value-Added Surplus Products (VASP)? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ye, H.; Bhatt, S.; Jeong, H.; Deutsch, J.; Ayaz, H.; Suri, R. Addressing Food Waste: How to Position Upcycled Foods to Different Generations. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 20, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Peschel, A.O. How Circular Will You Eat? The Sustainability Challenge in Food and Consumer Reaction to Either Waste-to-Value or yet Underused Novel Ingredients in Food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 77, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coderoni, S.; Perito, M.A. Sustainable Consumption in the Circular Economy. An Analysis of Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for Waste-to-Value Food. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, S.; Ardoin, R.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Willingness-to-Try Seafood Byproducts. Foods 2023, 12, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Cai, X.; Song, Y.; Jiang, H.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Q. Using Imagination to Overcome Fear: How Mental Simulation Nudges Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for Upcycled Food. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Akter, S.; Fogarassy, C. Analysis of Circular Thinking in Consumer Purchase Intention to Buy Sustainable Waste-To-Value (WTV) Foods. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coderoni, S.; Perito, M.A. Approaches for Reducing Wastes in the Agricultural Sector. An Analysis of Millennials’ Willingness to Buy Food with Upcycled Ingredients. Waste Manag. 2021, 126, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proserpio, C.; Fia, G.; Bucalossi, G.; Zanoni, B.; Spinelli, S.; Dinnella, C.; Monteleone, E.; Pagliarini, E. Winemaking Byproducts as Source of Antioxidant Components: Consumers’ Acceptance and Expectations of Phenol-Enriched Plant-Based Food. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo, C.; Lavelli, V.; Proserpio, C.; Laureati, M.; Pagliarini, E. Consumers’ Attitude towards Food by-Products: The Influence of Food Technology Neophobia, Education and Information. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perito, M.A.; Coderoni, S.; Russo, C. Consumer Attitudes towards Local and Organic Food with Upcycled Ingredients: An Italian Case Study for Olive Leaves. Foods 2020, 9, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, S.; Fu, R.; Goodman-Smith, F.; Lalor, F.; Crofton, E. Consumer Attitudes to Upcycled Foods in US and China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, 135919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; COM(2020) 381 Final; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Melios, S.; Johnson, H.; Grasso, S. Sensory Quality and Regulatory Aspects of Upcycled Foods: Challenges and Opportunities. Food Res. Int. 2025, 199, 115360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. National Strategy for Reducing Food Loss and Waste and Recycling Organics; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA; United States Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2025-02/14451_food-waste-strategy_v5_508.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Upcycled Certified. Where Food Comes From. Available online: https://www.wherefoodcomesfrom.com/upcycled (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a Scale to Measure the Trait of Food Neophobia in Humans. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.N.; Evans, G. Construction and Validation of a Psychometric Scale to Measure Consumers’ Fears of Novel Food Technologies: The Food Technology Neophobia Scale. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellali, W.; Koraï, B. The Impact of Innovation Level and Emotional Response on Upcycled Food Acceptance. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 107, 104849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perito, M.A.; Fonzo, A.D.; Sansone, M.; Russo, C. Consumer Acceptance of Food Obtained from Olive By-Products: A Survey of Italian Consumers. Br. Food J. 2019, 122, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimitri, P.; Michailidis, A.; Loizou, E.; Mantzouridou, F.T.; Gkatzionis, K.; Mugampoza, E.; Nastis, S.A. Novel Foods and Neophobia: Evidence from Greece, Cyprus, and Uganda. Resources 2022, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Ye, H.; Deutsch, J.; Ayaz, H.; Suri, R. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Upcycled Foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 86, 104035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Deutsch, J.; Suri, R. Differentiating Price Sensitivity from Willingness to Pay: Role of Pricing in Consumer Acceptance of Upcycled Foods. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2021, 27, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Ye, H.; Deutsch, J.; Jeong, H.; Zhang, J.; Suri, R. Food Waste and Upcycled Foods: Can a Logo Increase Acceptance of Upcycled Foods? J. Food Prod. Mark. 2021, 27, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Smith, F.; Bhatt, S.; Moore, R.; Mirosa, M.; Ye, H.; Deutsch, J.; Suri, R. Retail Potential for Upcycled Foods: Evidence from New Zealand. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschel, A.O.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. Sell More for Less or Less for More? The Role of Transparency in Consumer Response to Upcycled Food Products. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Lee, J.; Deutsch, J.; Ayaz, H.; Fulton, B.; Suri, R. From Food Waste to Value-Added Surplus Products (VASP): Consumer Acceptance of a Novel Food Product Category. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curutchet, A.; Trias, J.; Tárrega, A.; Arcia, P. Consumer Response to Cake with Apple Pomace as a Sustainable Source of Fibre. Foods 2021, 10, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, Y.; Kubota, S. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Reprocessed Fried Chicken: A Way of Reducing Uneaten Food. Appetite 2018, 120, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altintzoglou, T.; Honkanen, P.; Whitaker, R.D. Influence of the Involvement in Food Waste Reduction on Attitudes towards Sustainable Products Containing Seafood By-Products. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 125487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asioli, D.; Grasso, S. Do Consumers Value Food Products Containing Upcycled Ingredients? The Effect of Nutritional and Environmental Information. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 91, 104194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelick, A.; Sogari, G.; Rodolfi, M.; Dando, R.; Paciulli, M. Impact of Sustainability and Nutritional Messaging on Italian Consumers’ Purchase Intent of Cereal Bars Made with Brewery Spent Grains. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovai, D.; Michniuk, E.; Roseman, E.; Amin, S.; Lesniauskas, R.; Wilke, K.; Garza, J.; Lammert, A. Insects as a Sustainable Food Ingredient: Identifying and Classifying Early Adopters of Edible Insects Based on Eating Behavior, Familiarity, and Hesitation. J. Sens. Stud. 2021, 36, e12681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Gregory, P.J. Climate Change and Sustainable Food Production. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygorczyk, A.; Blake, A. Particle Perception: Defining Sensory Thresholds for Grittiness of Upcycled Apple Pomace Powders. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 111, 104985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Asioli, D.; Banovic, M.; Perito, M.A.; Peschel, A.O.; Stancu, V. Defining Upcycled Food: The Dual Role of Upcycling in Reducing Food Loss and Waste. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 132, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshtaghian, H.; Bolton, K.; Rousta, K. Challenges for Upcycled Foods: Definition, Inclusion in the Food Waste Management Hierarchy and Public Acceptability. Foods 2021, 10, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flock Chicken Skin Crisps Original 2.5 oz. Bag. Available online: https://boxncase.com/products/flock-chicken-skin-crisps-original-2-5-oz-bag (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Flock Chicken Skin Crisps. Available online: https://flockfoods.com/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Amazon.Com: Nut Free Cookies—Buttery Delicious & Crunchy Variety (2 Chocolate Chips, 1 Double Dutch Chocolate Chip, 1 Brown Sugar Oatmeal)—Non-GMO Bagged Cookies—Fancypants Baking Co.—4 Pack (5oz): Grocery & Gourmet Food. Available online: https://us.amazon.com/Fancypants-Cookies-Buttery-Delicious-Chocolate/dp/B07RZMRNRD (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Fancypants Baking Co. Authentic & Sustainable Cookies. Available online: https://fancypantsbakery.com/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Don’t Just Drink Beer—Eat It, Too; Food Gal. Available online: https://www.foodgal.com/2016/03/dont-just-drink-beer-eat-it-too/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Ingredients. Available online: https://upcycledfoods.com/ingredients/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Ascent Protein. Available online: https://www.ascentprotein.com/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Sulima, J. Matriark Foods Turns Wasted Vegetables Into Climate-Friendly Pantry Staples. Available online: https://www.thrillist.com/eat/nation/matriark-foods-climate-friendly-pantry-staples (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Matriark Foods. Available online: https://matriarkfoods.com/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Impossible Foods. Available online: https://impossiblefoods.com/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Rule Breaker Snacks. Available online: https://www.rulebreakersnacks.com/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Rule Breaker Singles Variety Pack 4-1.9 oz. Available online: https://www.target.com/p/rule-breaker-singles-variety-pack-4-1-9-oz/-/A-93108275 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Grain Berry: Antioxidant-Rich, Whole Grain Foods. Available online: https://grainberry.com/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Get to Know Our Animal-Free Dairy Partner, Brave Robot; Perfect Day. 2022. Available online: https://perfectday.com/blog/brave-robots-animal-free-ice-cream-the-future-favors-the-brave/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Shieber, J. Brave Robot Ice Cream Launches as the First Brand from the Perfect Day-Backed Urgent Company. TechCrunch. 2020. Available online: https://techcrunch.com/2020/07/15/brave-robot-ice-cream-launches-as-the-first-brand-from-the-perfect-day-backed-urgent-company/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Revol Greens. Available online: https://www.revolgreens.com/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Riemenschneider, P. Revol Greens Releases Three New Products. Blue Book. 2020. Available online: https://www.bluebookservices.com/revol-greens-releases-three-new-products/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- The Interceptors Resources. Available online: https://www.storymoneyimpact.com/resources-interceptors (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Sustainable Nutrition Scientific Board. What Is Sustainable Nutrition? Available online: https://sustainablenutrition-sb.com/about/infographics/ (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Upcycled Food Association. What Is Upcycled Food? 2020. Available online: https://foodtank.com/news/2020/05/upcycled-food-is-officially-defined-with-a-goal-of-paving-the-way-for-industry-food-waste-reduction/upcycled-food-infographic/ (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Asioli, D.; Banovic, M.; Perito, M.A.; Peschel, A.O. Consumer Understanding of Upcycled Foods—Exploring Consumer-Created Associations and Concept Explanations across Five Countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 112, 105033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teisl, M.F.; Fein, S.B.; Levy, A.S. Information Effects on Consumer Attitudes toward Three Food Technologies: Organic Production, Biotechnology, and Irradiation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardello, A.V.; Schutz, H.G.; Lesher, L.L. Consumer Perceptions of Foods Processed by Innovative and Emerging Technologies: A Conjoint Analytic Study. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2007, 8, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brian Kennedy; Alec Tyson How Americans View Climate Change and Policies to Address the Issue. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2024/12/09/how-americans-view-climate-change-and-policies-to-address-the-issue/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

| Demographics | Average n = 947 | Greenthusiasts n = 306 | Balanced Believers n = 347 | Healthy Hesitants n = 208 | Eco-Skeptics n = 86 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| 18–27 | 39.4 | 36.6 | 41.8 | 44.2 | 27.9 |

| 28–43 | 29.9 | 34.6 | 30.0 | 20.2 | 36.0 |

| 44–59 | 19.0 | 23.2 | 16.1 | 17.3 | 19.8 |

| 60–78 | 11.3 | 5.2 | 12.1 | 17.3 | 15.1 |

| 79–96 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| 97 and Over | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 26.0 | 23.5 | 25.1 | 26.9 | 36.0 |

| Female | 72.3 | 73.2 | 74.1 | 72.1 | 62.8 |

| Not Listed | 0.8 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Prefer Not to Answer | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| Ethnic Background | |||||

| White or Caucasian | 68.6 | 79.1 | 69.2 | 57.2 | 57.0 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 10.3 | 12.7 | 8.6 | 10.6 | 8.1 |

| Black or African-American | 5.3 | 2.3 | 4.6 | 7.2 | 14.0 |

| Native American or American Indian | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 2.3 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 20.9 | 12.7 | 22.8 | 29.3 | 22.1 |

| Not Listed | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Prefer Not to Answer | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.0 |

| Education Level | |||||

| Some High School | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| High School Graduate or Equivalent | 4.5 | 2.6 | 3.7 | 8.2 | 5.8 |

| Some College | 14.6 | 13.1 | 15.3 | 14.9 | 16.3 |

| Trade, Technical or Vocational Training | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 1.2 |

| Associate Degree | 5.8 | 4.2 | 6.6 | 5.3 | 9.3 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 40.7 | 42.5 | 45.0 | 36.1 | 27.9 |

| Master’s Degree | 26.8 | 27.1 | 24.2 | 28.4 | 32.6 |

| Professional Degree | 1.1 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.0 |

| Doctorate Degree | 5.2 | 6.9 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 7.0 |

| Student Status | |||||

| Yes | 36.7 | 32.0 | 39.2 | 40.4 | 34.9 |

| No | 63.3 | 68.0 | 60.8 | 59.6 | 65.1 |

| Employment Status | |||||

| Not Employed | 11.0 | 8.2 | 11.8 | 12.5 | 14.0 |

| Employed Part-Time | 20.5 | 17.3 | 20.5 | 25.5 | 19.8 |

| Employed Full-Time | 55.9 | 67.3 | 54.8 | 45.2 | 45.3 |

| Self Employed | 2.4 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 3.5 |

| Retired | 6.7 | 3.6 | 6.1 | 10.1 | 11.6 |

| Full-time Homemaker | 3.6 | 1.6 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 5.8 |

| Household Income | |||||

| Under USD 20,000 | 10.7 | 7.8 | 10.1 | 15.9 | 10.5 |

| USD 20,000 to USD 49,999 | 16.9 | 15.0 | 18.2 | 18.3 | 15.1 |

| USD 50,000 to USD 74,999 | 18.2 | 17.3 | 18.4 | 16.8 | 23.3 |

| USD 75,000 to USD 99,999 | 14.5 | 15.4 | 15.6 | 12.5 | 11.6 |

| USD 100,000 to USD 149,999 | 18.3 | 23.2 | 16.7 | 14.4 | 16.3 |

| USD 150,000 or more | 14.5 | 15.4 | 13.8 | 14.4 | 14.0 |

| Prefer not to answer | 7.1 | 5.9 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 9.3 |

| Current Residence | |||||

| West | 32.8 | 39.2 | 30.8 | 29.3 | 26.7 |

| Midwest | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 3.5 |

| South/South East | 63.8 | 58.2 | 67.4 | 64.9 | 66.3 |

| North East | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 3.4 | 3.5 |

| Outside of U.S. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Origin | |||||

| West | 31.9 | 36.9 | 31.1 | 29.3 | 23.3 |

| Midwest | 8.3 | 9.5 | 7.2 | 8.7 | 8.1 |

| South/South East | 35.4 | 32.4 | 38.3 | 32.2 | 41.9 |

| North East | 10.5 | 13.1 | 9.5 | 7.7 | 11.6 |

| Outside of U.S. | 13.9 | 8.2 | 13.8 | 22.1 | 15.1 |

| Awareness | Average n = 947 | Greenthusiasts n = 306 | Balanced Believers n = 347 | Healthy Hesitants n = 208 | Eco-Skeptics n = 86 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | |||||

| No, I have never heard of it | 4.3 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 7.7 | 7.0 |

| Yes, I have heard of it but I don’t know what it means | 37.8 | 32.4 | 35.7 | 44.2 | 50.0 |

| Yes, I have heard of it and I know what it means | 57.9 | 65.0 | 61.1 | 48.1 | 43.0 |

| Upcycling | |||||

| No, I have never heard of it | 44.4 | 37.3 | 42.7 | 53.8 | 53.5 |

| Yes, I have heard of it but I don’t know what it means | 30.8 | 33.3 | 32.9 | 26.0 | 25.6 |

| Yes, I have heard of it and I know what it means | 24.8 | 29.4 | 24.5 | 20.2 | 20.9 |

| Familiarity of Sustainable Food | Average n = 906 | Greenthusiasts n = 298 | Balanced Believers n = 336 | Healthy Hesitants n = 192 | Eco-Skeptics n = 80 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I am familiar with the concept of sustainability | |||||

| No | 3.31 | 2.01 | 2.38 | 4.17 | 10.00 |

| Maybe | 15.34 | 6.04 | 13.39 | 25.00 | 35.00 |

| Yes | 81.35 | 91.95 | 84.23 | 70.83 | 55.00 |

| I know what sustainable food is | |||||

| No | 9.60 | 6.71 | 10.12 | 8.85 | 20.00 |

| Maybe | 30.46 | 27.18 | 28.57 | 36.46 | 36.25 |

| Yes | 59.93 | 66.11 | 61.31 | 54.69 | 43.75 |

| I can think of examples of sustainable food(s) | |||||

| No | 18.87 | 13.09 | 19.94 | 20.31 | 32.50 |

| Maybe | 30.13 | 26.85 | 30.36 | 34.38 | 31.25 |

| Yes | 50.99 | 60.07 | 49.70 | 45.31 | 36.25 |

| I have eaten sustainable food(s) | |||||

| No | 5.52 | 2.01 | 5.65 | 5.21 | 18.75 |

| Maybe | 40.40 | 32.21 | 41.67 | 47.92 | 47.50 |

| Yes | 54.08 | 65.77 | 52.68 | 46.88 | 33.75 |

| I have purchased sustainable food(s) | |||||

| No | 9.38 | 4.36 | 10.42 | 8.85 | 25.00 |

| Maybe | 42.27 | 36.91 | 43.15 | 48.96 | 42.50 |

| Yes | 48.34 | 58.72 | 46.43 | 42.19 | 32.50 |

| I have read about and/or seen videos/documentaries about sustainable food(s) | |||||

| No | 27.59 | 23.83 | 28.27 | 29.17 | 35.00 |

| Maybe | 26.60 | 22.48 | 29.76 | 27.60 | 26.25 |

| Yes | 45.81 | 53.69 | 41.96 | 43.23 | 38.75 |

| I have heard about sustainable food(s) through marketing (products) and/or word of mouth | |||||

| No | 10.60 | 8.05 | 12.50 | 8.85 | 16.25 |

| Maybe | 26.16 | 22.15 | 25.89 | 28.13 | 37.50 |

| Yes | 63.25 | 69.80 | 61.61 | 63.02 | 46.25 |

| Familiarity of Upcycled Food | Average n = 527 | Greenthusiasts n = 192 | Balanced Believers n = 199 | Healthy Hesitants n = 96 | Eco-Skeptics n = 40 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I am familiar with the concept of upcycling | |||||

| No | 11.39 | 6.77 | 11.56 | 17.71 | 17.50 |

| Maybe | 28.08 | 23.44 | 32.16 | 26.04 | 35.00 |

| Yes | 60.53 | 69.79 | 56.28 | 56.25 | 47.50 |

| I know what upcycled food is | |||||

| No | 14.99 | 13.02 | 18.09 | 13.54 | 12.50 |

| Maybe | 39.66 | 35.42 | 40.20 | 43.75 | 47.50 |

| Yes | 45.35 | 51.56 | 41.71 | 42.71 | 40.00 |

| I can think of examples of upcycled food(s) | |||||

| No | 30.36 | 27.60 | 32.66 | 30.21 | 32.50 |

| Maybe | 33.59 | 30.21 | 35.18 | 35.42 | 37.50 |

| Yes | 36.05 | 42.19 | 32.16 | 34.38 | 30.00 |

| I have eaten upcycled food(s) | |||||

| No | 17.65 | 11.98 | 16.08 | 23.96 | 37.50 |

| Maybe | 53.89 | 55.21 | 57.79 | 51.04 | 35.00 |

| Yes | 28.46 | 32.81 | 26.13 | 25.00 | 27.50 |

| I have purchased upcycled food(s) | |||||

| No | 29.22 | 20.83 | 32.16 | 33.33 | 45.00 |

| Maybe | 47.25 | 51.04 | 48.24 | 45.83 | 27.50 |

| Yes | 23.53 | 28.13 | 19.60 | 20.83 | 27.50 |

| I have read about and/or seen videos/documentaries about upcycled food(s) | |||||

| No | 43.07 | 41.15 | 48.24 | 41.67 | 30.00 |

| Maybe | 26.94 | 24.48 | 23.62 | 37.50 | 30.00 |

| Yes | 29.98 | 34.38 | 28.14 | 20.83 | 40.00 |

| I have heard about upcycled food(s) through marketing (products) and/or word of mouth | |||||

| No | 24.10 | 21.35 | 28.64 | 22.92 | 17.50 |

| Maybe | 32.45 | 32.29 | 29.15 | 37.50 | 37.50 |

| Yes | 43.45 | 46.35 | 42.21 | 39.58 | 45.00 |

| Product Concepts | Greenthusiasts n = 306 | Balanced Believers n = 347 | Healthy Hesitants n = 208 | Eco-Skeptics n = 86 | Average n = 947 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Δ | Pre | Post | Δ | Pre | Post | Δ | Pre | Post | Δ | Δ | |

| Sustainable | |||||||||||||

| Beef | 93.5 | 97.1 | 3.6 | 90.2 | 94.2 | 4 | 85.6 | 90.4 | 4.8 | 79.1 | 79.1 | 0.0 | 3.1 |

| Greens | 97.7 | 97.4 | −0.3 | 91.9 | 95.1 | 3.2 | 89.9 | 89.4 | −0.5 | 81.4 | 88.4 | 7.0 | 2.4 |

| Cookies | 90.8 | 95.4 | 4.6 | 91.1 | 94.8 | 3.7 | 87.5 | 91.3 | 3.8 | 81.4 | 84.9 | 3.5 | 3.9 |

| Cereal | 88.6 | 92.8 | 4.2 | 82.1 | 90.2 | 8.1 | 77.9 | 85.6 | 7.7 | 79.1 | 83.7 | 4.6 | 6.2 |

| Ice Cream | 91.2 | 96.4 | 5.2 | 88.2 | 92.5 | 4.3 | 83.2 | 89.4 | 6.2 | 80.2 | 79.1 | −1.1 | 3.7 |

| Upcycled | |||||||||||||

| Whey | 83.3 | 94.8 | 11.5 | 79.0 | 90.2 | 11.2 | 71.6 | 85.6 | 14 | 69.8 | 81.4 | 11.6 | 12.1 |

| Cookies | 92.2 | 97.4 | 5.2 | 89.6 | 95.7 | 6.1 | 83.2 | 90.4 | 7.2 | 74.4 | 81.4 | 7.0 | 6.4 |

| Granola | 97.7 | 98.4 | 0.7 | 96.0 | 96.8 | 0.8 | 89.4 | 94.2 | 4.8 | 84.9 | 89.5 | 4.6 | 2.7 |

| Chicken | 93.5 | 97.4 | 3.9 | 89.6 | 96.3 | 6.7 | 86.5 | 91.8 | 5.3 | 75.6 | 83.7 | 8.1 | 6.0 |

| Tomato | 81.0 | 92.2 | 11.2 | 81.3 | 89.6 | 8.3 | 76.9 | 86.1 | 9.2 | 74.4 | 86.0 | 11.6 | 10.1 |

| Cost | Average n = 947 | Greenthusiasts n = 306 | Balanced Believers n = 347 | Healthy Hesitants n = 208 | Eco-Skeptics n = 86 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I would be willing to pay slightly more for an upcycled food product | 11.7 | 15.7 | 11.8 | 8.7 | 4.7 |

| I would buy an upcycled food product if the price was similar to the traditional product | 65.4 | 75.2 | 67.7 | 57.2 | 40.7 |

| I would buy an upcycled food product if the price was slightly less than the traditional product | 20.6 | 9.2 | 20.5 | 30.3 | 38.4 |

| I would NOT buy an upcycled food product, regardless of price | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 16.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, K.; DeGeorge, D.; Diehn, D.; Galatz, A.; Garza, J.; McGowan, L.; Drake, M.; Amin, S.; Lammert, A. Upcycled vs. Sustainable: Identifying Consumer Segments and Recognition of Sustainable and Upcycled Foods Within the United States. Foods 2025, 14, 3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203508

Chu K, DeGeorge D, Diehn D, Galatz A, Garza J, McGowan L, Drake M, Amin S, Lammert A. Upcycled vs. Sustainable: Identifying Consumer Segments and Recognition of Sustainable and Upcycled Foods Within the United States. Foods. 2025; 14(20):3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203508

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Karissa, Daniel DeGeorge, Dan Diehn, Alissa Galatz, Jeff Garza, Lucy McGowan, MaryAnne Drake, Samir Amin, and Amy Lammert. 2025. "Upcycled vs. Sustainable: Identifying Consumer Segments and Recognition of Sustainable and Upcycled Foods Within the United States" Foods 14, no. 20: 3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203508

APA StyleChu, K., DeGeorge, D., Diehn, D., Galatz, A., Garza, J., McGowan, L., Drake, M., Amin, S., & Lammert, A. (2025). Upcycled vs. Sustainable: Identifying Consumer Segments and Recognition of Sustainable and Upcycled Foods Within the United States. Foods, 14(20), 3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203508