What Makes Consumers Behave Sustainably When It Comes to Food Waste? An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

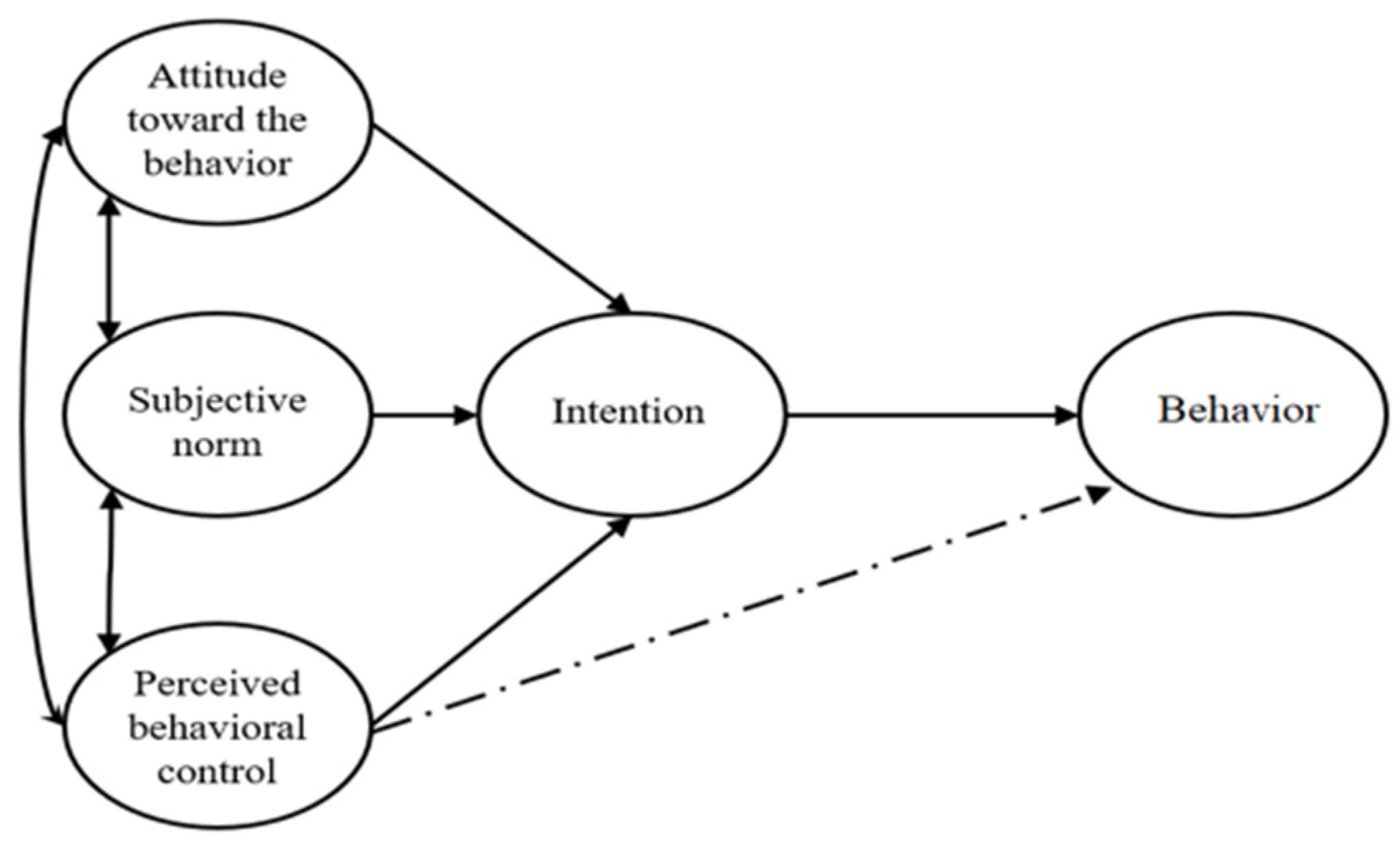

2.2. Conceptual Framework and Data Analysis

- Description of the model: the structural model is specified, including the causal relationship between items and constructs.

- Validity and reliability of the model.

- Assessment of the structural model: to know the effect and the significance of relationships established between variables (path coefficient and p value).

2.3. Cluster Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondent Classification

3.2. SEM Analysis

3.3. Hypothesis Evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. General Model

4.2. Cluster Comparisons

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mesías, F.J.; Fernández, J.A.; Horrillo, A.; Escribano, A.J. An Approach to the Perceptions of Spanish Consumers on Food Sustainability through the Use of Projective Techniques. New Medit. 2023, 22, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. SAVE FOOD: Global Initiative: On Food Loss and Waste Reduction—Definitional Framework of Food Loss; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Stewart, A.; Smith, E.; Warne, T.; Byker-Shanks, C. Consumer Perceptions, Behaviors, and Knowledge of Food Waste in a Rural American State. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, M.; Falasconi, L. Addressing Food Wastage in the Framework of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Waste Manag. Res. 2018, 36, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardra, S.; Barua, M.K. Halving Food Waste Generation by 2030: The Challenges and Strategies of Monitoring UN Sustainable Development Goal Target 12.3. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bajželj, B.; Quested, T.E.; Röös, E.; Swannell, R.P.J. The Role of Reducing Food Waste for Resilient Food Systems. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 45, 101140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Statistics Division (ESS). Available online: https://www.fao.org/food-agriculture-statistics/en/ (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Kummu, M.; de Moel, H.; Porkka, M.; Siebert, S.; Varis, O.; Ward, P.J. Lost Food, Wasted Resources: Global Food Supply Chain Losses and Their Impacts on Freshwater, Cropland, and Fertiliser Use. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 438, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, M.; Pastorello, T.; Carlesso, A.; Tesser, S.; Semenzin, E. Quantifying Environmental Implications of Surplus Food Redistribution to Reduce Food Waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizcano-Prada, J.; Mesías, F.J.; Lami, O.; Sama-Berrocal, C.; Maestre-Matos, M. Gestión Sostenible de Los Alimentos. Una Aplicación de La Teoría Del Comportamiento Planificado En El Contexto de Un País Emergente: Colombia. ITEA Inf. Tec. Econ. Agrar. 2024, 120, 397–423. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Initiative Mondiale de Réduction des Pertes et du Gaspillage Alimentaires; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2021; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat Food Waste per Capita in the EU Remained Stable in 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Food_waste_and_food_waste_prevention_-_estimates (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Bengtsson, M.; Alfredsson, E.; Cohen, M.; Lorek, S.; Schroeder, P. Transforming Systems of Consumption and Production for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: Moving beyond Efficiency. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1533–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K.A.; Cassidy, E.S.; Gerber, J.S.; Johnston, M.; Mueller, N.D.; O’Connell, C.; Ray, D.K.; West, P.C.; et al. Solutions for a Cultivated Planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Pucci, T.; Caputo, V.; Van Loo, E.J. The Theory of Planned Behaviour and Healthy Diet: Examining the Mediating Effect of Traditional Food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 104, 104709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.K.; Mishra, A.; Singh, S.; Jaiswal, D. Household Food Waste and Theory of Planned Behavior: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 97645–97659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, S.V.; Young, C.W.; Unsworth, K.L.; Robinson, C. Bringing Habits and Emotions into Food Waste Behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, E.; Sahin, H.; Topaloglu, Z.; Oledinma, A.; Huda, A.K.S.; Irani, Z.; Sharif, A.M.; van’t Wout, T.; Kamrava, M. A Consumer Behavioural Approach to Food Waste. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2018, 31, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Mirzaii, F.; Rahnama, M.; Alidoost, F. A Theoretical Framework for Explaining the Determinants of Food Waste Reduction in Residential Households: A Case Study of Mashhad, Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 6774–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistic of Spain. España en Cifras 2019; National Institute of Statistic of Spain: Madrid, Spain, 2019; 60p. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prodyser/espa_cifras/2019/ (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Stone, D.H. Design a Questionnaire. Br. Med. J. 1993, 307, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.H.; Nguyen, P.M. Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Norm Activation Model to Investigate Organic Food Purchase Intention: Evidence from Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 14, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, B.A.; Casey, L.M. Technological Adjuncts to Increase Adherence to Therapy: A Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.F.; Charoghchian Khorasani, E.; Namkhah, Z.; Afzal Aghaee, M.; Peyman, N. Factors Affecting Food Waste Management Behavior in Iran: A Systematic Review Based on Behavioral Theories. J. Nutr. Fasting Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, B.; Chaturvedi, S.; Bhati, N.S. Extending the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Sustainable Food Consumption. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 31277–31300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, N.A.A.; Sulaiman, N.; Zainal Badari, S.A.; Sabran, M.R. Mindful Eating for a Sustainable Future: Predicting Organic Food Consumption among Malaysian Adults Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2024, 20, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soorani, F.; Ahmadvand, M. Determinants of Consumers’ Food Management Behavior: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Waste Manag. 2019, 98, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Werf, P.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J.A. Food for Thought: Comparing Self-Reported versus Curbside Measurements of Household Food Wasting Behavior and the Predictive Capacity of Behavioral Determinants. Waste Manag. 2020, 101, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehman, J.M.; Babbitt, C.W.; Flynn, C. What Predicts and Prevents Source Separation of Household Food Waste? An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretter, C.; Unsworth, K.L.; Russell, S.V.; Quested, T.E.; Doriza, A.; Kaptan, G. Corrigendum to <‘Don’t Put All Your Eggs in One Basket: Testing an Integrative Model of Household Food Waste’>. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre-Matos, M.; Lombana-Coy, J.; Mesías, F.J. Creation of Shared Value in Cooperatives: Informal Institutions’ Perspective of Small-Sized Banana Growers from Colombia. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2023, 28, 134–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780130329295. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM Methods for Research in Social Sciences and Technology Forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach for Structural Equation Modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Methodology for Business and Management; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. ISBN 0-8058-2677-7 (Hardcover)/0-8058-3093-6 (Paperback). [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, N.; Karunasena, G.G.; Pearson, D. Food Waste in Australian Households: Role of Shopping Habits and Personal Motivations. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 1523–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó-Bódi, B.; Kasza, G.; Szakos, D. Assessment of Household Food Waste in Hungary. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakos, D.; Szabó-Bódi, B.; Kasza, G. Consumer Awareness Campaign to Reduce Household Food Waste Based on Structural Equation Behavior Modeling in Hungary. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 24580–24589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kritikou, T.; Panagiotakos, D.; Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K. Investigating the Determinants of Greek Households Food Waste Prevention Behaviour. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiak, M.; Kruger, D.; Kruger, J.S.; Sorokowski, P. Moral Judgments of Food Wasting Predict Food Wasting Behavior. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 3547–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Gil, N.Y.; Favila-Cisneros, H.J.; Zaragoza-Alonso, J.; Cuffia, F.; Rojas-Rivas, E. Using Projective Techniques and Food Neophobia Scale to Explore the Perception of Traditional Ethnic Foods in Central Mexico: A Preliminary Study on the Beverage Sende. J. Sens. Stud. 2020, 35, e12606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Book Review: Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Werts, C.E.; Linn, R.L.; Jöreskog, K.G. Intraclass Reliability Estimates: Testing Structural Assumptions. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent and Asymptotically Normal PLS Estimators for Linear Structural Equations. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2015, 81, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. Bridging Design and Behavioral Research With Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 0805802835. [Google Scholar]

- Dalila; Latif, H.; Jaafar, N.; Aziz, I.; Afthanorhan, A. The Mediating Effect of Personal Values on the Relationships between Attitudes, Subjective Norms, Perceived Behavioral Control and Intention to Use. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.H.; Saleem, F.; Zakariya, R.; Ahmad, A. The Determinants of Food Waste Behavior in Young Consumers in a Developing Country. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 1953–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, A.M.; Grappi, S.; Romani, S. “The Road to Food Waste Is Paved with Good Intentions”: When Consumers’ Goals Inhibit the Minimization of Household Food Waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, L.; Francioni, B.; Murmura, F.; Savelli, E. Factors Affecting Household Food Waste among Young Consumers and Actions to Prevent It. A Comparison among UK, Spain and Italy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, A.C.; Olthof, M.R.; Boevé, A.J.; van Dooren, C.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Brouwer, I.A. Socio-Demographic Predictors of Food Waste Behavior in Denmark and Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Deliberador, L.; Octávio-Batalha, M.; Aldara da Silva, C.; Masood-Azeem, M.; Lee-Lane, J.; Rodrigues-Silva, P. Why Do We Waste so Much Food? Understanding Household Food Waste through a Theoretical Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 137974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ling, M.; Lu, Y.; Shen, M. Understanding Household Waste Separation Behaviour: Testing the Roles of Moral, Past Experience, and Perceived Policy Effectiveness within the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Sustainability 2017, 9, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.M. Determinants of Food Waste: TPB and Moderating Impact of Demographics & Guilt. J. Glob. Hosp. Tour. 2023, 2, 157–182. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli, M.; Sun, Z.; McDade, E.; Snitz, B.; Hughes, T.; Jacobsen, E.; Chang, C.C.H. That’s Inappropriate! Social Norms in an Older Population-Based Cohort. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2018, 32, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaus, C.J.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M.; Ellison, B. Wasted Food: A Qualitative Study of U.S. Young Adults’ Perceptions, Beliefs and Behaviors. Appetite 2018, 130, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-C.; Chen, X.; Yang, C. Consumer Food Waste Behavior among Emerging Adults: Evidence from China. Foods 2020, 9, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Yiridoe, E. A Behavioural Model of Urban Household Food Waste Reduction: An Empirical Study in Beijing, China. In Environmental Sustainability in Emerging Markets: Consumer, Organisation and Policy Perspectives; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jungowska, J.; Kulczyński, B.; Sidor, A.; Gramza-Michałowska, A. Assessment of Factors Affecting the Amount of Food Waste in Households Run by Polish Women Aware of Well-Being. Sustainability 2021, 13, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyam, M.; Chuanmin, S.; Qasim, H.; Ihtisham, M.; Anjum, R.; Jiaxin, L.; Tikhomirova, A.; Khan, N. Food Consumption Behavior of Pakistani Students Living in China: The Role of Food Safety and Health Consciousness in the Wake of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 673771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viccaro, M.; Coppola, A.; D’Angelo, M.C.; Genovese, F.; Romano, S.; Cozzi, M. Young People Are Not All the Same! The Theory of Planned Behaviour Applied to Food Waste Behaviour across Young Italian Generations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Barbera, F.; Amato, M.; Riverso, R.; Verneau, F. Social Emotions and Good Provider Norms in Tackling Household Food Waste: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, B.; Cudjoe, D.; Farrukh, M.; Bai, R. What Influences Students’ Food Waste Behaviour in Campus Canteens? Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porpino, G.; Wanink, B.; Juracy, P. From the Table to Waste: An Exploratory Study on Behaviour towards Food Waste of Spanish and Italian Youths. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Informe Sobre el Desperdicio Alimentario en los Hogares 2021; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2021.

- Partearroyo, T.; Samaniego-Vaesken, M.; Ruiz, E.; Aranceta-Bartrina, J.; González-Gross, M.; Varela-Moreiras, G. Plate waste generated by Spanish households and out-of-home consumption: Results from the ANIBES study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items |

|---|---|

| Attitude [31,32] | |

| AT1 | It upsets me when unused food products end up in the waste bin or garburator. |

| AT2 | I believe that being aware about the difference between “use by” and “best before” dates is very important to reduce food waste. |

| AT3 | Food waste is immoral while other people are starving. |

| AT4 | I think that wasting food is a waste of money. |

| AT5 | I sometimes think about reducing food waste. |

| AT6 | Preventing food waste is everyone’s responsibility. |

| AT7 | I always think about the environment when I throw away food. |

| Subjective Norms [33] | |

| SN1 | Most of my family and friends are sensitive to food waste and always try to avoid it. |

| SN2 | I do not usually provide several different types of meals so that everyone can eat what he/she likes when I have guests./I try to provide the right quantity of meals needed when I have guests to avoid leftovers. |

| SN3 | If I generate food waste, my family/friends would find it undesirable. |

| SN4 | In my area, social pressure makes me feel guilty when I throw away food. |

| SN5 | Reducing household food waste will benefit future generations. |

| SN6 | Reducing household food waste is the duty of a responsible citizen. |

| Perceived Behavioral Control [32] | |

| PBC1 | I find it easy to prepare a new meal from leftovers. |

| PBC2 | I find it easy to plan my food shopping in such a way that all the food I purchase is eaten. |

| PBC3 | Before I prepare food, I always consider precisely how much I need to prepare and what I will do with the leftovers. |

| PBC4 | I always plan the meals in my household ahead and I keep to this plan. |

| PBC5 | I do not think eating food leftovers results in any health damage. |

| Intention [32,34] | |

| IN1 | I intend to use all the leftovers. |

| IN2 | I try to check the best-before dates of the food products I have at home to avoid wasting. |

| IN3 | I intend to reduce the amount of food wasted by paying more attention to my purchases. |

| IN4 | I intend to reduce the amount of food wasted by paying more attention to my portions. |

| Behavior [31,34] | |

| B1 | I check what I have at home before food shopping. |

| B2 | I make a shopping list before shopping and do shopping according to it. |

| B3 | I buy the needed amount of food even when there are promotions. |

| B4 | To minimize waste, I try to buy smaller amounts of food. |

| B5 | In my family, the leftovers are eaten in the same form or reused in other meals. |

| B6 | I adjust my meal plan to use leftovers. |

| Item | Answer | C1: Women Involved in Food Purchasing and Cooking (27.9%) | C2: Older Men Quite Involved in Food Purchasing and Cooking (28.9%) | C3: Middle-Aged Affluent Male Foodies (33.2%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In charge of household food purchasing *** (%) | Always | 100 | 36.2 | |

| Sometimes | 38.4 | 74.7 | ||

| Rarely | 25.4 | 25.3 | ||

| Frequency of cooking at home *** (%) | Daily | 100 | 100 | |

| Sometimes | 75.6 | |||

| Rarely | 24.4 | |||

| Sex * (%) | Female | 58 | 48.7 | 47.7 |

| Male | 42 | 51.3 | 52.3 | |

| Age ** (%) | 18–35 years old | 31.5 | 26.5 | 22.4 |

| 36–55 years old | 32 | 27.2 | 37.1 | |

| >55 years old | 36.5 | 46.3 | 40.5 | |

| Income ** (%) | <1000 €/month | 7.1 | 4.3 | 4.3 |

| 1001–2000 €/month | 29.9 | 30.1 | 18.7 | |

| 2001–3000 €/month | 27.9 | 27.2 | 32.3 | |

| >3000 €/month | 35.1 | 38.4 | 44.7 |

| Construct | Indicator | Loading (λ) | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (rho_a) | Composite Reliability (rho_c) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample | ||||||

| Attitude | AT1 | 0.722 | ||||

| AT2 | 0.705 | |||||

| AT3 | 0.788 | 0.804 | 0.806 | 0.865 | 0.562 | |

| AT4 | 0.803 | |||||

| AT6 | 0.725 | |||||

| Behavior | B1 | 0.669 | 0.722 | 0.771 | 0.824 | 0.545 |

| B2 | 0.568 | |||||

| B5 | 0.819 | |||||

| B6 | 0.860 | |||||

| Intention | IN1 | 0.652 | ||||

| IN2 | 0.784 | 0.782 | 0.782 | 0.861 | 0.610 | |

| IN3 | 0.854 | |||||

| IN4 | 0.819 | |||||

| PBC | PBC1 | 0.625 | 0.701 | 0.702 | 0.806 | 0.512 |

| PBC2 | 0.707 | |||||

| PBC3 | 0.774 | |||||

| PBC4 | 0.746 | |||||

| SN | SN1 | 0.936 | 0.849 | 0.851 | 0.930 | 0.869 |

| SN2 | 0.928 | |||||

| Women involved in food purchasing and cooking | ||||||

| Attitude | AT1 | 0.722 | ||||

| AT2 | 0.724 | |||||

| AT3 | 0.788 | 0.757 | 0.759 | 0.837 | 0.507 | |

| AT4 | 0.697 | |||||

| AT6 | 0.651 | |||||

| Behavior | B1 | 0.649 | 0.720 | 0.818 | 0.820 | 0.546 |

| B2 | 0.479 | |||||

| B5 | 0.860 | |||||

| B6 | 0.891 | |||||

| Intention | IN1 | 0.704 | ||||

| IN2 | 0.800 | 0.790 | 0.791 | 0.863 | 0.613 | |

| IN3 | 0.838 | |||||

| IN4 | 0.784 | |||||

| PBC | PBC1 | 0.680 | 0.704 | 0.713 | 0.816 | 0.526 |

| PBC2 | 0.667 | |||||

| PBC3 | 0.769 | |||||

| PBC4 | 0.780 | |||||

| SN | SN1 | 0.952 | 0.890 | 0.893 | 0.948 | 0.901 |

| SN2 | 0.946 | |||||

| Older men quite involved in food purchasing and cooking | ||||||

| Attitude | AT1 | 0.764 | ||||

| AT2 | 0.739 | |||||

| AT3 | 0.827 | 0.839 | 0.842 | 0.886 | 0.611 | |

| AT4 | 0.854 | |||||

| AT6 | 0.713 | |||||

| Behavior | B1 | 0.673 | 0.702 | 0.731 | 0.815 | 0.527 |

| B2 | 0.607 | |||||

| B5 | 0.770 | |||||

| B6 | 0.832 | |||||

| Intention | IN1 | 0.591 | ||||

| IN2 | 0.756 | 0.751 | 0.757 | 0.845 | 0.582 | |

| IN3 | 0.562 | |||||

| IN4 | 0.833 | |||||

| PBC | PBC1 | 0.656 | 0.701 | 0.703 | 0.779 | 0.504 |

| PBC2 | 0.744 | |||||

| PBC3 | 0.702 | |||||

| PBC4 | 0.635 | |||||

| SN | SN1 | 0.935 | 0.832 | 0.842 | 0.922 | 0.856 |

| SN2 | 0.915 | |||||

| Middle-aged affluent male foodies | ||||||

| Attitude | AT1 | 0.678 | ||||

| AT2 | 0.656 | |||||

| AT3 | 0.781 | 0.803 | 0.816 | 0.864 | 0.561 | |

| AT4 | 0.821 | |||||

| AT6 | 0.795 | |||||

| Behavior | B1 | 0.685 | 0.748 | 0.792 | 0.839 | 0.570 |

| B2 | 0.599 | |||||

| B5 | 0.842 | |||||

| B6 | 0.862 | |||||

| Intention | IN1 | 0.656 | ||||

| IN2 | 0.818 | 0.807 | 0.806 | 0.875 | 0.639 | |

| IN3 | 0.870 | |||||

| IN4 | 0.828 | |||||

| PBC | PBC1 | 0.545 | 0.702 | 0.715 | 0.808 | 0.585 |

| PBC2 | 0.631 | |||||

| PBC3 | 0.836 | |||||

| PBC4 | 0.804 | |||||

| SN | SN1 | 0.924 | 0.834 | 0.834 | 0.923 | 0.858 |

| SN2 | 0.928 | |||||

| Construct | Attitudes | Behavior | Intention | PBC | SN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample | |||||

| Attitude | 0.750 | ||||

| Behavior | 0.474 | 0.738 | |||

| Intention | 0.505 | 0.492 | 0.781 | ||

| PBC | 0.326 | 0.580 | 0.417 | 0.715 | |

| SN | 0.633 | 0.344 | 0.420 | 0.212 | 0.932 |

| C1: Women involved in food purchasing and cooking | |||||

| Attitude | 0.712 | ||||

| Behavior | 0.417 | 0.739 | |||

| Intention | 0.484 | 0.440 | 0.783 | ||

| PBC | 0.245 | 0.608 | 0.333 | 0.726 | |

| SN | 0.554 | 0.378 | 0.444 | 0.138 | 0.949 |

| C2: Older men quite involved in food purchasing and cooking | |||||

| Attitude | 0.781 | ||||

| Behavior | 0.597 | 0.726 | |||

| Intention | 0.522 | 0.562 | 0.763 | ||

| PBC | 0.382 | 0.570 | 0.433 | 0.685 | |

| SN | 0.674 | 0.419 | 0.425 | 0.252 | 0.925 |

| C3: Middle-aged affluent male foodies | |||||

| Attitude | 0.749 | ||||

| Behavior | 0.380 | 0.755 | |||

| Intention | 0.542 | 0.483 | 0.799 | ||

| PBC | 0.277 | 0.549 | 0.449 | 0.765 | |

| SN | 0.638 | 0.239 | 0.406 | 0.192 | 0.926 |

| FIT | Overall Sample | C1: Women Involved in Food Purchasing and Cooking | C2: Older Men Quite Involved in Food Purchasing and Cooking | C3: Middle-Aged Affluent Male Foodies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2_Behavior | 0.242 | 0.194 | 0.316 | 0.234 |

| R2_Intention | 0.343 | 0.328 | 0.346 | 0.396 |

| SRMR | 0.079 | 0.092 | 0.088 | 0.089 |

| NFI | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

| Variables/Tested Relationship | Path Coefficients | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample | ||||

| Attitude → Intention | 0.310 | 0.046 | 6.712 | 0.000 *** |

| Intention → Behavior | 0.492 | 0.037 | 13.201 | 0.000 *** |

| PBC → Intention | 0.281 | 0.036 | 7.819 | 0.000 *** |

| SN → Intention | 0.164 | 0.052 | 3.136 | 0.002 ** |

| C1: Women involved in food purchasing and cooking | ||||

| Attitude → Intention | 0.289 | 0.092 | 3.148 | 0.002 ** |

| Intention → Behavior | 0.440 | 0.069 | 6.380 | 0.000 *** |

| PBC → Intention | 0.227 | 0.067 | 3.401 | 0.000 *** |

| SN → Intention | 0.253 | 0.103 | 2.451 | 0.014 ** |

| C2: Older men quite involved in food purchasing and cooking | ||||

| Attitude → Intention | 0.325 | 0.069 | 4.707 | 0.000 *** |

| Intention → Behavior | 0.562 | 0.052 | 10.765 | 0.000 *** |

| PBC → Intention | 0.274 | 0.059 | 4.642 | 0.000 *** |

| SN → Intention | 0.137 | 0.074 | 1.857 | 0.063 |

| C3: Middle-aged affluent male foodies | ||||

| Attitude → Intention | 0.393 | 0.073 | 5.400 | 0.000 *** |

| Intention → Behavior | 0.483 | 0.069 | 7.014 | 0.000 *** |

| PBC → Intention | 0.322 | 0.055 | 5.900 | 0.000 *** |

| SN → Intention | 0.093 | 0.084 | 1.112 | 0.266 |

| F-Square | Overall Sample | Effect * | C1: Women Involved in Food Purchasing and Cooking | Effect | C2: Older Men Quite Involved in Food Purchasing and Cooking | Effect | C3: Middle-Aged Affluent Male Foodies | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude→ Intention | 0.082 | Small | 0.083 | Small | 0.080 | Small | 0.121 | Moderate |

| Intention→ Behavior | 0.319 | Moderate | 0.240 | Moderate | 0.463 | Large | 0.302 | Moderate |

| PBC → Intention | 0.108 | Small | 0.072 | Small | 0.098 | Small | 0.208 | Moderate |

| SN → Intention | 0.024 | Small | 0.066 | Small | 0.016 | Small | 0.009 | Small |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lizcano-Prada, J.; Ayouaz, R.; Mesías, F.J.; Maestre-Matos, L.-M. What Makes Consumers Behave Sustainably When It Comes to Food Waste? An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Spain. Foods 2025, 14, 2306. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132306

Lizcano-Prada J, Ayouaz R, Mesías FJ, Maestre-Matos L-M. What Makes Consumers Behave Sustainably When It Comes to Food Waste? An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Spain. Foods. 2025; 14(13):2306. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132306

Chicago/Turabian StyleLizcano-Prada, Julieth, Radia Ayouaz, Francisco J. Mesías, and Leydis-Marcela Maestre-Matos. 2025. "What Makes Consumers Behave Sustainably When It Comes to Food Waste? An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Spain" Foods 14, no. 13: 2306. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132306

APA StyleLizcano-Prada, J., Ayouaz, R., Mesías, F. J., & Maestre-Matos, L.-M. (2025). What Makes Consumers Behave Sustainably When It Comes to Food Waste? An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Spain. Foods, 14(13), 2306. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132306