The Connection Between Socioeconomic Factors and Dietary Habits of Children with Down Syndrome in Croatia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

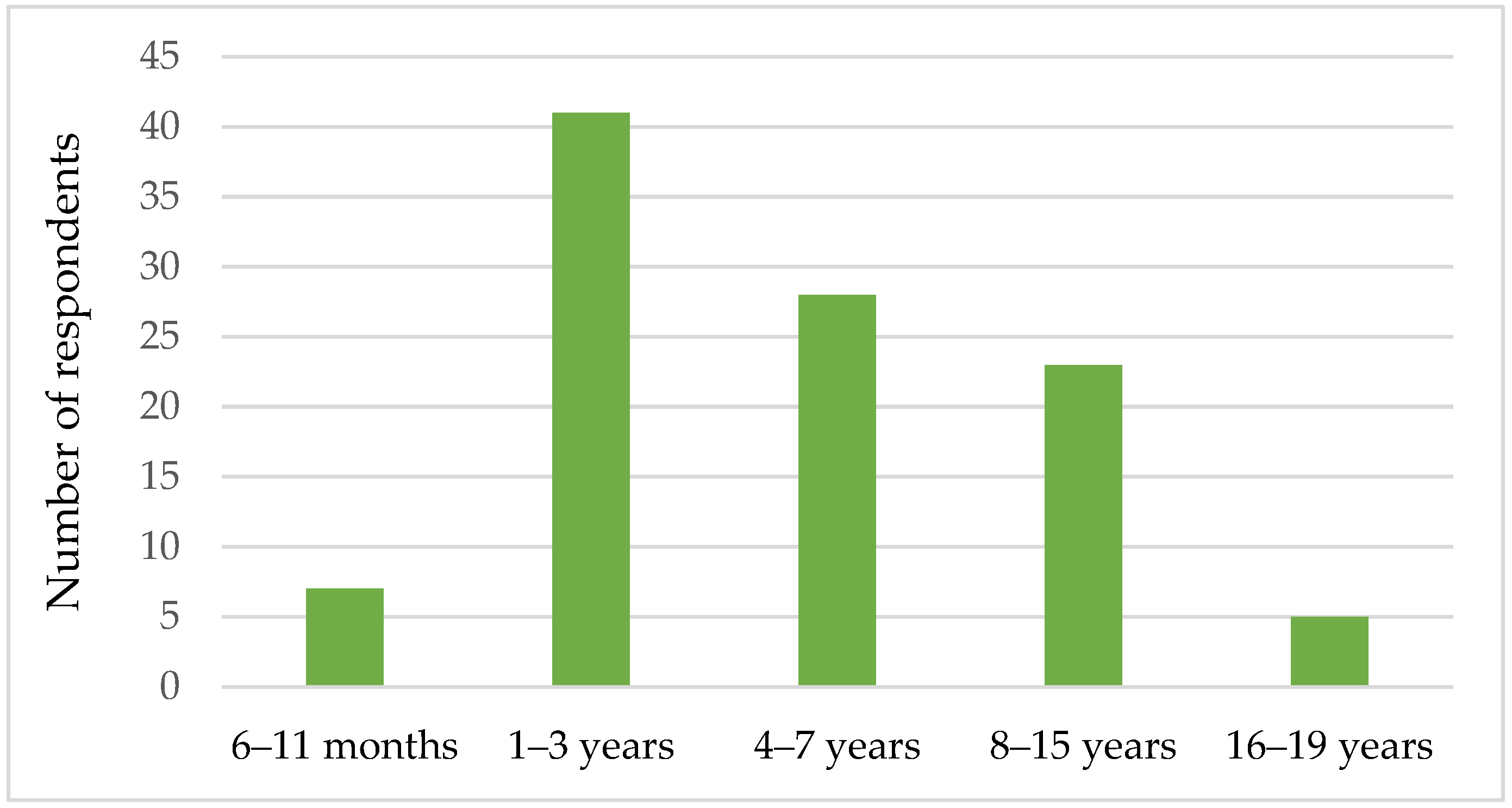

3.1. Nutritional and Health Status of Children with Down Syndrome

3.2. Analysis of Respondents’ Grocery Shopping Habits in Relation to Place of Residence

3.3. Dietary Habits of Children with Down Syndrome

3.3.1. Analysis of Respondents’ Dietary Habits in Relation to Gender and Place of Residence

Carbohydrate-Rich Foods Consumption

Milk and Dairy Products Consumption

Fruit and Vegetables Consumption

Protein-Rich Food Consumption

Oils and Fats, Nuts and Seeds Consumption

Fast Food, Sweets, and Snack Consumption

Liquids Consumption

3.3.2. Analysis of Respondents’ Dietary Habits in Relation to Parental Educational Attainment

Carbohydrate-Rich Foods Consumption

Milk and Dairy Products Consumption

Fruit and Vegetable Consumption

Protein-Rich Food Consumption

Oils and Fats, Nuts and Seeds Consumption

Fast Food, Sweets, and Snack Consumption

Liquids Consumption

3.3.3. Analysis of Respondents’ Dietary Habits in Relation to Mother’s Employment Status and Monthly Financial Expenditure on Food

Carbohydrate-Rich Foods Consumption

Milk and Dairy Products Consumption

Fruits and Vegetables Consumption

Protein-Rich Food Consumption

Oil, Fat, Nut, and Seed Consumption

Fast Food, Sweets, and Snack Consumption

Liquids Consumption

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Franceschetti, S.; Tofani, M.; Mazzafoglia, S.; Pizza, F.; Capuano, E.; Raponi, M.; Della Bella, G.; Cerchiari, A. Assessment and Rehabilitation Intervention of Feeding and Swallowing Skills in Children with Down Syndrome Using the Global Intensive Feeding Therapy (GIFT). Children 2024, 11, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ruparelia, A.; Mobley, W.C. Down Syndrome. In Neurobiology of Brain Disorders; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 59–77. ISBN 978-0-12-398270-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mégarbané, A.; Ravel, A.; Mircher, C.; Sturtz, F.; Grattau, Y.; Rethoré, M.-O.; Delabar, J.-M.; Mobley, W.C. The 50th Anniversary of the Discovery of Trisomy 21: The Past, Present, and Future of Research and Treatment of Down Syndrome. Genet. Med. 2009, 11, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dijk, M.; Lipke-Steenbeek, W. Measuring Feeding Difficulties in Toddlers with Down Syndrome. Appetite 2018, 126, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, M.J.; The Committee on Genetics. Health Supervision for Children With Down Syndrome. Pediatrics 2011, 128, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentis, A.F. Epigenomic Engineering for Down Syndrome. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 71, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Serrano, J.L.; Kang, H.J.; Tyler, W.A.; Silbereis, J.C.; Cheng, F.; Zhu, Y.; Pletikos, M.; Jankovic-Rapan, L.; Cramer, N.P.; Galdzicki, Z.; et al. Down Syndrome Developmental Brain Transcriptome Reveals Defective Oligodendrocyte Differentiation and Myelination. Neuron 2016, 89, 1208–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenini, G.; Fiorini, A.; Sultana, R.; Perluigi, M.; Cai, J.; Klein, J.B.; Head, E.; Butterfield, D.A. An Investigation of the Molecular Mechanisms Engaged before and after the Development of Alzheimer Disease Neuropathology in Down Syndrome: A Proteomics Approach. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 76, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydar, T.F.; Reeves, R.H. Trisomy 21 and Early Brain Development. Trends Neurosci. 2012, 35, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roizen, N.J.; Magyar, C.I.; Kuschner, E.S.; Sulkes, S.B.; Druschel, C.; Van Wijngaarden, E.; Rodgers, L.; Diehl, A.; Lowry, R.; Hyman, S.L. A Community Cross-Sectional Survey of Medical Problems in 440 Children with Down Syndrome in New York State. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccatello, G.; Cocchi, G.; Dimastromatteo, R.T.; Cavallo, A.; Biserni, G.B.; Selicati, M.; Forchielli, M.L. Eating and Lifestyle Habits in Youth With Down Syndrome Attending a Care Program: An Exploratory Lesson for Future Improvements. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 641112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptomey, L.T.; Oreskovic, N.M.; Hendrix, J.A.; Nichols, D.; Agiovlasitis, S. Weight Management Recommendations for Youth with Down Syndrome: Expert Recommendations. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 10, 1064108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, D.; Garland, M.; Williams, K. Correlates of Specific Childhood Feeding Problems. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2003, 39, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, A.C.; Richter, G.T. Pharyngeal Dysphagia in Children with Down Syndrome. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2013, 149, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.; Maybee, J.; Moran, M.K.; Wolter-Warmerdam, K.; Hickey, F. Clinical Characteristics of Dysphagia in Children with Down Syndrome. Dysphagia 2016, 31, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narawane, A.; Eng, J.; Rappazzo, C.; Sfeir, J.; King, K.; Musso, M.F.; Ongkasuwan, J. Airway Protection & Patterns of Dysphagia in Infants with down Syndrome: Videofluoroscopic Swallow Study Findings & Correlations. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 132, 109908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.F.; Bernhard, C.B.; Surette, V.; Hasted, A.; Wakeling, I.; Smith-Simpson, S. Eating Behaviors in Children with Down Syndrome: Results of a Home-use Test. J. Texture Stud. 2022, 53, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, M.A.; Shabnam, S.; Narayanan, S. Feeding and Swallowing Difficulties in Children with Down Syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2019, 63, 992–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assery, M.K.; Albusaily, H.S.; Pani, S.C.; Aldossary, M.S. Bite Force and Occlusal Patterns in the Mixed Dentition of Children with Down Syndrome. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.F.; Bernhard, C.B.; Smith-Simpson, S. Parent-reported Ease of Eating Foods of Different Textures in Young Children with Down Syndrome. J. Texture Stud. 2019, 50, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surette, V.A.; Bernhard, C.B.; Smith-Simpson, S.; Ross, C.F. Development of a Home-use Method for the Evaluation of Food Products by Children with and without Down Syndrome. J. Texture Stud. 2021, 52, 424–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Dwyer, J.; Holland, M. Overcoming Weight Problems in Adults With Down Syndrome. Nutr. Today 2014, 49, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, K.; Rimmer, J.H.; Heller, T. Obesity and Associated Factors in Adults with Intellectual Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2014, 58, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandini, L.G.; Fleming, R.K.; Scampini, R.; Gleason, J.; Must, A. Is Body Mass Index a Useful Measure of Excess Body Fatness in Adolescents and Young Adults with Down Syndrome? J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2013, 57, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertapelli, F.; Pitetti, K.; Agiovlasitis, S.; Guerra-Junior, G. Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome—Prevalence, Determinants, Consequences, and Interventions: A Literature Review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 57, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypek, M.; Koch, W.; Goral, K.; Soczyńska, K.; Poźniak, O.; Cichoń, K.; Przybysz, O.; Czop, M. Analysis of the Diet Quality and Nutritional State of Children, Youth and Young Adults with an Intellectual Disability: A Multiple Case Study. Preliminary Polish Results. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaili, T.M.; Attlee, A.; Naveed, H.; Maklai, H.; Mahmoud, M.; Hamadeh, N.; Asif, T.; Hasan, H.; Obaid, R.S. Physical Status and Parent-Child Feeding Behaviours in Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome in The United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiverling, L.; Hendy, H.M.; Williams, K. The Screening Tool of Feeding Problems Applied to Children (STEP-CHILD): Psychometric Characteristics and Associations with Child and Parent Variables. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białek-Dratwa, A.; Żur, S.; Wilemska-Kucharzewska, K.; Szczepańska, E.; Kowalski, O. Nutrition as Prevention of Diet-Related Diseases—A Cross-Sectional Study among Children and Young Adults with Down Syndrome. Children 2022, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleri, P.; Mazzuca, G.; Pietrobelli, A.; Zampieri, N.; Piacentini, G.; Zaffanello, M.; Pecoraro, L. The Role of Diet and Physical Activity in Obesity and Overweight in Children with Down Syndrome in Developed Countries. Children 2024, 11, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura Paroche, M.; Caton, S.J.; Vereijken, C.M.J.L.; Weenen, H.; Houston-Price, C. How Infants and Young Children Learn About Food: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrøm, M.; Retterstøl, K.; Hope, S.; Kolset, S.O. Nutritional Challenges in Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datar, A.; Nicosia, N.; Shier, V. Maternal Work and Children’s Diet, Activity, and Obesity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 107, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.W.; Hearst, M.O.; Escoto, K.; Berge, J.M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Parental Employment and Work-Family Stress: Associations with Family Food Environments. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauch, C.E.; Wycherley, T.P.; Bell, L.K.; Laws, R.A.; Byrne, R.; Golley, R.K. Parental Work Hours and Household Income as Determinants of Unhealthy Food and Beverage Intake in Young Australian Children. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croatian Institute for Public Health. Report on Persons with Disabilities in the Republic of Croatia; Croatian Institute for Public Health: Zagreb, Croatia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC Growth Charts; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024.

- Bertapelli, F.; Agiovlasitis, S.; Machado, M.R.; Do Val Roso, R.; Guerra-Junior, G. Growth Charts for Brazilian Children with Down Syndrome: Birth to 20 Years of Age. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertapelli, F.; Machado, M.R.; Roso, R.D.V.; Guerra-Júnior, G. Body Mass Index Reference Charts for Individuals with Down Syndrome Aged 2–18 Years. J. Pediatr. 2017, 93, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrelid, A.; Gustafsson, J.; Ollars, B.; Annerén, G. Growth Charts for Down’s Syndrome from Birth to 18 Years of Age. Arch. Dis. Child. 2002, 87, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.; Kritzinger, A. Parental Experiences of Feeding Problems in Their Infants with Down Syndrome. Downs Syndr. Res. Pract. 2004, 9, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlen, J.E.G. The Down Syndrome Nutrition Handbook: A Guide to Promoting Healthy Lifestyles, 2nd ed.; Phronesis Publishing, LLC.: Portland, OR, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-9786118-0-4. [Google Scholar]

- Magenis, M.L.; Machado, A.G.; Bongiolo, A.M.; Silva, M.A.D.; Castro, K.; Perry, I.D.S. Dietary Practices of Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 22, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravel, A.; Mircher, C.; Rebillat, A.-S.; Cieuta-Walti, C.; Megarbane, A. Feeding Problems and Gastrointestinal Diseases in Down Syndrome. Arch. Pédiatrie 2020, 27, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisacane, A.; Toscano, E.; Pirri, I.; Continisio, P.; Andria, G.; Zoli, B.; Strisciuglio, P.; Concolino, D.; Piccione, M.; Giudice, C.L.; et al. Down Syndrome and Breastfeeding. Acta Paediatr. 2003, 92, 1479–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sarheed, M. Feeding Habits of Children with Down’s Syndrome Living in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2005, 52, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hielscher, L.; Irvine, K.; Ludlow, A.K.; Rogers, S.; Mengoni, S.E. A Scoping Review of the Complementary Feeding Practices and Early Eating Experiences of Children With Down Syndrome. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2023, 48, 914–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Croatia. Available online: https://mpudt.gov.hr/sustav-lokalne-i-podrucne-regionalne-samouprave/22979?lang=hr (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Dean, W.R.; Sharkey, J.R. Rural and Urban Differences in the Associations between Characteristics of the Community Food Environment and Fruit and Vegetable Intake. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegler, M.C.; Prakash, R.; Hermstad, A.; Anderson, K.; Haardörfer, R.; Raskind, I.G. Food Acquisition Practices, Body Mass Index, and Dietary Outcomes by Level of Rurality. J. Rural Health 2022, 38, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacko, A.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B. Urban vs. Rural Socioeconomic Differences in the Nutritional Quality of Household Packaged Food Purchases by Store Type. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, T.M.D.; Pereira, K.S.F.; Tahim, J.C.; Sichieri, R.; Bezerra, I.N. Places to Purchase Food in Urban and Rural Areas of Brazil. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2024, 27, e240047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colić-Barić, I.; Kajfež, R.; Šatalić, Z.; Cvjetić, S. Comparison of Dietary Habits in the Urban and Rural Croatian Schoolchildren. Eur. J. Nutr. 2004, 43, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sila, S.; Pavić, A.M.; Hojsak, I.; Ilić, A.; Pavić, I.; Kolaček, S. Comparison of Obesity Prevalence and Dietary Intake in School-Aged Children Living in Rural and Urban Area of Croatia. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2018, 23, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, M.M.; Bel-Serrat, S.; Kelleher, C.C.; Buoncristiano, M.; Spinelli, A.; Nardone, P.; Milanović, S.M.; Rito, A.I.; Bosi, A.T.B.; Gutiérrrez-González, E.; et al. Urban and Rural Differences in Frequency of Fruit, Vegetable, and Soft Drink Consumption among 6–9-year-old Children from 19 Countries from the WHO European Region. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkkilä, A.T.; Herrington, D.M.; Mozaffarian, D.; Lichtenstein, A.H. Cereal Fiber and Whole-Grain Intake Are Associated with Reduced Progression of Coronary-Artery Atherosclerosis in Postmenopausal Women with Coronary Artery Disease. Am. Heart J. 2005, 150, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amr, N.H. Thyroid Disorders in Subjects with Down Syndrome: An Update. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 2018, 89, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brdar, D.; Gunjača, I.; Pleić, N.; Torlak, V.; Knežević, P.; Punda, A.; Polašek, O.; Hayward, C.; Zemunik, T. The Effect of Food Groups and Nutrients on Thyroid Hormone Levels in Healthy Individuals. Nutrition 2021, 91–92, 111394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszka, J.; Włodarek, D. General Dietary Recommendations for People with Down Syndrome. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, S.; Parkin, K.L.; Fennema, O.R. Fennema’s Food Chemistry, 4th ed.; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-62870-571-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zmijewski, P.A.; Gao, L.Y.; Saxena, A.R.; Chavannes, N.K.; Hushmendy, S.F.; Bhoiwala, D.L.; Crawford, D.R. Fish Oil Improves Gene Targets of Down Syndrome in C57BL and BALB/c Mice. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourre, J.M. Roles of Unsaturated Fatty Acids (Especially Omega-3 Fatty Acids) in the Brain at Various Ages and during Ageing. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2004, 8, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Schuchardt, J.P.; Huss, M.; Stauss-Grabo, M.; Hahn, A. Significance of Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs) for the Development and Behaviour of Children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2010, 169, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lott, I.T. Antioxidants in Down Syndrome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Basis Dis. 2012, 1822, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.; Raza, S.T.; Ahmed, F.; Ahmad, A.; Abbas, S.; Mahdi, F. The Role of Vitamin e in Human Health and Some Diseases. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2014, 14, e157–e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, C.J.; Burford, D. Should Children Drink More Water? Appetite 2009, 52, 776–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, H.; Kavouras, S.A. Water Intake and Hydration State in Children. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ansem, W.J.; Schrijvers, C.T.; Rodenburg, G.; Van De Mheen, D. Maternal Educational Level and Children’s Healthy Eating Behaviour: Role of the Home Food Environment (Cross-Sectional Results from the INPACT Study). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Alvira, J.M.; Mouratidou, T.; Bammann, K.; Hebestreit, A.; Barba, G.; Sieri, S.; Reisch, L.; Eiben, G.; Hadjigeorgiou, C.; Kovacs, E.; et al. Parental Education and Frequency of Food Consumption in European Children: The IDEFICS Study. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, S.; Asakura, K.; Sasaki, S.; Nishiwaki, Y. Relationship between Maternal Employment Status and Children’s Food Intake in Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2021, 26, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möser, A.; Chen, S.E.; Jilcott, S.B.; Nayga, R.M. Associations between Maternal Employment and Time Spent in Nutrition-Related Behaviours among German Children and Mothers. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1256–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | n (F) | Average Percentile Weight-for-Age F | n (F) < 5th Percentile | n (F) 85th –94th Percentile | n (F) > 95th Percentile | n (M) | Average Percentile Weight-for-Age M | n (M) < 5th Percentile | n (M) 85th –94th Percentile | n (M) > 95th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–11 months | 1 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 50 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 |

| 1–3 years | 17 | 56 | 1 (5.9%) | 3 (17.6%) | 0 | 24 | 61 | 3 (12.5%) | 4 (16.7%) | 4 (16.7%) |

| 4–7 years | 5 | 62 | 0 | 1 (20%) | 0 | 23 | 69 | 2 (8.7%) | 5 (21.7%) | 3 (13.1%) |

| 8–15 years | 6 | 75 | 0 | 2 (33.3%) | 0 | 17 | 62 | 0 | 3 (17.6%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| 16–19 years | 3 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Single Answers Only | All Answers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Answer | Urban (n = 59) | Rural (n = 45) | p | p Global | Urban (n = 59) | Rural (n = 45) | p | p Global |

| Where do you most often buy fresh fruits and vegetables? | At the local market | 14 | 6 | 0.176 | 0.293 | 33 | 14 | 0.07 | 0.084 |

| In large retail chains | 12 | 10 | 1.000 | 22 | 17 | 0.849 | |||

| Directly from the manufacturer | 2 | 1 | 1.000 | 12 | 6 | 0.61 | |||

| I don’t buy. We produce ourselves | 8 | 12 | 0.113 | 17 | 22 | 0.035 | |||

| Where do you most often buy fresh meat? | At the local market | 8 | 8 | 0.589 | 0.052 | 19 | 11 | 0.529 | 0.015 |

| In large retail chains | 21 | 7 | 0.019 | 28 | 11 | 0.034 | |||

| Directly from the manufacturer | 13 | 12 | 0.637 | 21 | 19 | 0.448 | |||

| I don’t buy. We produce ourselves | 4 | 9 | 0.067 | 5 | 13 | 0.009 | |||

| Where do you most often buy other food? | In small specialty stores | 8 | 14 | 0.051 | 0.051 | ||||

| In large retail chains | 51 | 31 | 0.051 | ||||||

| Question | Gender | Place of Residence | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How Often Does Your Child with Down Syndrome Consume: | Frequency of Consumption | F (n = 32) | M (n = 72) | F (%) | M (%) | p | p Global | U (n = 59) | R (n = 45) | U (%) | R (%) | p | p Global |

| White/semi-white bread | Two or more times a day | 6 | 14 | 18.75 | 19.44 | 1.000 | 0.797 | 7 | 13 | 11.86 | 28.89 | 0.043 | 0.162 |

| Once a day | 8 | 15 | 25.00 | 20.83 | 0.620 | 15 | 8 | 25.42 | 17.78 | 0.475 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 3 | 6 | 9.38 | 8.33 | 1.000 | 6 | 3 | 10.17 | 6.67 | 0.729 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 6 | 9 | 18.75 | 12.50 | 0.550 | 11 | 4 | 18.64 | 8.89 | 0.260 | |||

| Rarely/never | 9 | 28 | 28.13 | 38.89 | 0.380 | 20 | 17 | 33.90 | 37.78 | 0.686 | |||

| Black/wholemeal bread | Two or more times a day | 3 | 3 | 9.38 | 4.17 | 0.370 | 0.810 | 5 | 1 | 8.47 | 2.22 | 0.231 | 0.295 |

| Once a day | 2 | 8 | 6.25 | 11.11 | 0.720 | 5 | 5 | 8.47 | 11.11 | 0.743 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 2 | 5 | 6.25 | 6.94 | 1.000 | 4 | 3 | 6.78 | 6.67 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 5 | 11 | 15.63 | 15.28 | 1.000 | 12 | 4 | 20.34 | 8.89 | 0.169 | |||

| Rarely/never | 20 | 45 | 62.50 | 62.50 | 1.000 | 33 | 32 | 55.93 | 71.11 | 0.153 | |||

| Whole grains such as barley, oats, etc., in the form of grains, groats, or flour | Two or more times a day | 2 | 8 | 6.25 | 11.11 | 0.720 | 0.807 | 4 | 6 | 6.78 | 13.33 | 0.323 | 0.225 |

| Once a day | 11 | 17 | 34.38 | 23.61 | 0.340 | 20 | 8 | 33.90 | 17.78 | 0.078 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 2 | 6 | 6.25 | 8.33 | 1.000 | 6 | 2 | 10.17 | 4.44 | 0.461 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 6 | 17 | 18.75 | 23.61 | 0.800 | 12 | 11 | 20.34 | 24.44 | 0.641 | |||

| Rarely/never | 11 | 24 | 34.38 | 33.33 | 1.000 | 17 | 18 | 28.81 | 40.00 | 0.296 | |||

| Potatoes | Two or more times a day | 1 | 2 | 3.13 | 2.78 | 1.000 | 0.291 | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 6.67 | 0.078 | 0.069 |

| once a day | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 4.17 | 0.550 | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 6.67 | 0.078 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 7 | 0.00 | 9.72 | 0.100 | 4 | 3 | 6.78 | 6.67 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 27 | 53 | 84.38 | 73.61 | 0.310 | 49 | 31 | 83.05 | 68.89 | 0.104 | |||

| Rarely/never | 4 | 7 | 12.50 | 9.72 | 0.730 | 6 | 5 | 10.17 | 11.11 | 1.000 | |||

| Pasta | Two or more times a day | 1 | 1 | 3.13 | 1.39 | 0.520 | 0.839 | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 4.44 | 0.185 | 0.105 |

| Once a day | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 2.78 | 1.000 | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 4.44 | 0.185 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 2 | 3.13 | 2.78 | 1.000 | 3 | 0 | 5.08 | 0.00 | 0.256 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 22 | 53 | 68.75 | 73.61 | 0.640 | 44 | 31 | 74.58 | 68.89 | 0.659 | |||

| Rarely/never | 8 | 14 | 25.00 | 19.44 | 0.600 | 12 | 10 | 20.34 | 22.22 | 0.814 | |||

| Rice | Two or more times a day | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 4.17 | 0.550 | 0.841 | 1 | 2 | 1.69 | 4.44 | 0.577 | 0.650 |

| Once a day | 2 | 1 | 6.25 | 1.39 | 0.220 | 1 | 2 | 1.69 | 4.44 | 0.577 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | |||

| Once or twice a week | 23 | 52 | 71.88 | 72.22 | 1.000 | 45 | 30 | 76.27 | 66.67 | 0.378 | |||

| Rarely/never | 7 | 16 | 21.88 | 22.22 | 1.000 | 12 | 11 | 20.34 | 24.44 | 0.641 | |||

| Milk | Two or more times a day | 5 | 11 | 15.63 | 15.28 | 1.000 | 0.839 | 9 | 7 | 15.25 | 15.56 | 1.000 | 0.022 |

| Once a day | 6 | 16 | 18.75 | 22.22 | 0.800 | 18 | 4 | 30.51 | 8.89 | 0.008 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 5 | 10 | 15.63 | 13.89 | 0.770 | 8 | 7 | 13.56 | 15.56 | 0.786 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 5 | 8 | 15.63 | 11.11 | 0.530 | 9 | 4 | 15.25 | 8.89 | 0.384 | |||

| Rarely/never | 11 | 27 | 34.38 | 37.50 | 0.830 | 15 | 23 | 25.42 | 51.11 | 0.008 | |||

| Fermented dairy products (yogurt, cream, kefir, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 2 | 8 | 6.25 | 11.11 | 0.720 | 0.076 | 5 | 5 | 8.47 | 11.11 | 0.743 | 0.053 |

| Once a day | 4 | 21 | 12.50 | 29.17 | 0.084 | 13 | 12 | 22.03 | 26.67 | 0.647 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 12 | 12 | 37.50 | 16.67 | 0.025 | 10 | 14 | 16.95 | 31.11 | 0.104 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 9 | 14 | 28.13 | 19.44 | 0.440 | 19 | 4 | 32.20 | 8.89 | 0.005 | |||

| Rarely/never | 5 | 17 | 15.63 | 23.61 | 0.440 | 12 | 10 | 20.34 | 22.22 | 0.814 | |||

| Cheese | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.516 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.306 |

| Once a day | 2 | 6 | 6.25 | 8.33 | 1.000 | 4 | 4 | 6.78 | 8.89 | 0.724 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 8 | 3.13 | 11.11 | 0.270 | 3 | 6 | 5.08 | 13.33 | 0.171 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 15 | 26 | 46.88 | 36.11 | 0.390 | 27 | 14 | 45.76 | 31.11 | 0.158 | |||

| Rarely/never | 14 | 32 | 43.75 | 44.44 | 1.000 | 25 | 21 | 42.37 | 46.67 | 0.694 | |||

| Fruit | Two or more times a day | 8 | 21 | 25.00 | 29.17 | 0.810 | 0.607 | 14 | 15 | 23.73 | 33.33 | 0.378 | 0.484 |

| Once a day | 16 | 24 | 50.00 | 33.33 | 0.130 | 26 | 14 | 44.07 | 31.11 | 0.314 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 5 | 13 | 15.63 | 18.06 | 1.000 | 10 | 8 | 16.95 | 17.78 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 2 | 9 | 6.25 | 12.50 | 0.500 | 7 | 4 | 11.86 | 8.89 | 0.753 | |||

| Rarely/never | 1 | 5 | 3.13 | 6.94 | 0.660 | 2 | 4 | 3.39 | 8.89 | 0.399 | |||

| Vegetables | Two or more times a day | 4 | 13 | 12.50 | 18.06 | 0.575 | 0.748 | 7 | 10 | 11.86 | 22.22 | 0.187 | 0.309 |

| Once a day | 12 | 29 | 37.50 | 40.28 | 0.831 | 26 | 15 | 44.07 | 33.33 | 0.314 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 9 | 18 | 28.13 | 25.00 | 0.810 | 17 | 10 | 28.81 | 22.22 | 0.504 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 3 | 8 | 9.38 | 11.11 | 1.000 | 4 | 7 | 6.78 | 15.56 | 0.201 | |||

| Rarely/never | 4 | 4 | 12.50 | 5.56 | 0.247 | 5 | 3 | 8.47 | 6.67 | 1.000 | |||

| Meat | Two or more times a day | 0 | 8 | 0.00 | 11.11 | 0.056 | 0.263 | 4 | 4 | 6.78 | 8.89 | 0.724 | 0.583 |

| Once a day | 9 | 18 | 28.13 | 25.00 | 0.810 | 15 | 12 | 25.42 | 26.67 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 12 | 29 | 37.50 | 40.28 | 0.831 | 27 | 14 | 45.76 | 31.11 | 0.158 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 9 | 12 | 28.13 | 16.67 | 0.195 | 10 | 11 | 16.95 | 24.44 | 0.460 | |||

| Rarely/never | 2 | 5 | 6.25 | 6.94 | 1.000 | 3 | 4 | 5.08 | 8.89 | 0.463 | |||

| Meat products (salami, hot dogs, pâté, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 1 | 3 | 3.13 | 4.17 | 1.000 | 0.989 | 4 | 0 | 6.78 | 0.00 | 0.131 | 0.225 |

| Once a day | 3 | 6 | 9.38 | 8.33 | 1.000 | 5 | 4 | 8.47 | 8.89 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 3 | 9 | 9.38 | 12.50 | 0.751 | 4 | 8 | 6.78 | 17.78 | 0.121 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 9 | 18 | 28.13 | 25.00 | 0.810 | 15 | 12 | 25.42 | 26.67 | 1.000 | |||

| Rarely/never | 16 | 36 | 50.00 | 50.00 | 1.000 | 31 | 21 | 52.54 | 46.67 | 0.694 | |||

| Eggs | Two or more times a day | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 2.78 | 1.000 | 0.790 | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 4.44 | 0.185 | 0.548 |

| Once a day | 1 | 4 | 3.13 | 5.56 | 1.000 | 2 | 3 | 3.39 | 6.67 | 0.650 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 2 | 7 | 6.25 | 9.72 | 0.718 | 5 | 4 | 8.47 | 8.89 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 19 | 33 | 59.38 | 45.83 | 0.288 | 30 | 22 | 50.85 | 48.89 | 1.000 | |||

| Rarely/never | 10 | 26 | 31.25 | 36.11 | 0.663 | 22 | 14 | 37.29 | 31.11 | 0.540 | |||

| Fish | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.788 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.929 |

| once a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 2 | 3.13 | 2.78 | 1.000 | 2 | 1 | 3.39 | 2.22 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 15 | 40 | 46.88 | 55.56 | 0.524 | 32 | 23 | 54.24 | 51.11 | 0.844 | |||

| Rarely/never | 16 | 30 | 50.00 | 41.67 | 0.522 | 25 | 21 | 42.37 | 46.67 | 0.694 | |||

| Olive oil | Two or more times a day | 1 | 6 | 3.13 | 8.33 | 0.430 | 0.829 | 3 | 4 | 5.08 | 8.89 | 0.463 | 0.730 |

| Once a day | 5 | 13 | 15.63 | 18.06 | 1.000 | 11 | 7 | 18.64 | 15.56 | 0.796 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 6 | 10 | 18.75 | 13.89 | 0.560 | 11 | 5 | 18.64 | 11.11 | 0.412 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 5 | 10 | 15.63 | 13.89 | 0.770 | 9 | 6 | 15.25 | 13.33 | 1.000 | |||

| Rarely/never | 15 | 33 | 46.88 | 45.83 | 1.000 | 25 | 23 | 42.37 | 51.11 | 0.430 | |||

| Coconut oil | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.456 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.469 |

| Once a day | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.39 | 1.000 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 2.22 | 0.433 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 2.78 | 1.000 | 2 | 0 | 3.39 | 0.00 | 0.504 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 4 | 4 | 12.50 | 5.56 | 2.320 | 4 | 4 | 6.78 | 8.89 | 0.724 | |||

| rarely/never | 28 | 65 | 87.50 | 90.28 | 0.430 | 53 | 40 | 89.83 | 88.89 | 1.000 | |||

| Refined oils and saturated fats (sunflower oil, canola oil, lard, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 2.78 | 1.000 | 0.554 | 1 | 1 | 1.69 | 2.22 | 1.000 | 0.239 |

| Once a day | 6 | 9 | 18.75 | 12.50 | 0.546 | 12 | 3 | 20.34 | 6.67 | 0.055 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 7 | 11 | 21.88 | 15.28 | 0.413 | 10 | 8 | 16.95 | 17.78 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 8 | 19 | 25.00 | 26.39 | 1.000 | 12 | 15 | 20.34 | 33.33 | 0.176 | |||

| Rarely/never | 11 | 31 | 34.38 | 43.06 | 0.517 | 24 | 18 | 40.68 | 40.00 | 1.000 | |||

| Butter | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.267 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.487 |

| Once a day | 2 | 4 | 6.25 | 5.56 | 1.000 | 3 | 3 | 5.08 | 6.67 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 2 | 8 | 6.25 | 11.11 | 0.720 | 8 | 2 | 13.56 | 4.44 | 0.181 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 13 | 16 | 40.63 | 22.22 | 0.062 | 16 | 13 | 27.12 | 28.89 | 1.000 | |||

| Rarely/never | 15 | 44 | 46.88 | 61.11 | 0.202 | 32 | 27 | 54.24 | 60.00 | 0.690 | |||

| Fast food (burgers, pizza, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.39 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 2.22 | 0.433 | 0.641 |

| Once a day | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.39 | 1.000 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 2.22 | 0.433 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.39 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 1.69 | 0.00 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 5 | 11 | 15.63 | 15.28 | 1.000 | 9 | 7 | 15.25 | 15.56 | 1.000 | |||

| Rarely/never | 27 | 58 | 84.38 | 80.56 | 0.786 | 49 | 36 | 83.05 | 80.00 | 0.799 | |||

| Sweets (biscuits, cakes, chocolate, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 2 | 1 | 6.25 | 1.39 | 0.223 | 0.186 | 1 | 2 | 1.69 | 4.44 | 0.577 | 0.341 |

| Once a day | 3 | 12 | 9.38 | 16.67 | 0.384 | 7 | 8 | 11.86 | 17.78 | 0.414 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 7 | 7 | 21.88 | 9.72 | 0.121 | 8 | 6 | 13.56 | 13.33 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 12 | 24 | 37.50 | 33.33 | 0.824 | 18 | 18 | 30.51 | 40.00 | 0.406 | |||

| Rarely/never | 8 | 28 | 25.00 | 38.89 | 0.188 | 25 | 11 | 42.37 | 24.44 | 0.064 | |||

| Salty snacks (crackers, pretzels, chips, flips, popcorn, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 2 | 4 | 6.25 | 5.56 | 1.000 | 0.920 | 2 | 4 | 3.39 | 8.89 | 0.399 | 0.615 |

| Once a day | 5 | 10 | 15.63 | 13.89 | 0.772 | 7 | 8 | 11.86 | 17.78 | 0.414 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 5 | 7 | 15.63 | 9.72 | 0.507 | 7 | 5 | 11.86 | 11.11 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 10 | 26 | 31.25 | 36.11 | 0.663 | 23 | 13 | 38.98 | 28.89 | 0.306 | |||

| Rarely/never | 10 | 25 | 31.25 | 34.72 | 0.824 | 20 | 15 | 33.90 | 33.33 | 1.000 | |||

| Nuts (walnuts, almonds, hazelnuts, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.214 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.490 |

| Once a day | 1 | 9 | 3.13 | 12.50 | 0.169 | 5 | 5 | 8.47 | 11.11 | 0.743 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 0 | 3.13 | 0.00 | 0.308 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 2.22 | 0.433 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 12 | 22 | 37.50 | 30.56 | 0.504 | 22 | 12 | 37.29 | 26.67 | 0.295 | |||

| Rarely/never | 18 | 41 | 56.25 | 56.94 | 1.000 | 32 | 27 | 54.24 | 60.00 | 0.690 | |||

| Seeds (chia, pumpkin, flax, sesame, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.39 | 1.000 | 0.174 | 1 | 0 | 1.69 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.452 |

| Once a day | 3 | 6 | 9.38 | 8.33 | 1.000 | 5 | 4 | 8.47 | 8.89 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 5 | 2 | 15.63 | 2.78 | 0.286 | 4 | 3 | 6.78 | 6.67 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 7 | 17 | 21.88 | 23.61 | 1.000 | 17 | 7 | 28.81 | 15.56 | 0.159 | |||

| Rarely/never | 17 | 46 | 53.13 | 63.89 | 0.696 | 32 | 31 | 54.24 | 68.89 | 0.158 | |||

| Carbonated drinks and syrups | Two or more times a day | 2 | 4 | 6.25 | 5.56 | 1.000 | 0.550 | 4 | 2 | 6.78 | 4.44 | 0.696 | 0.961 |

| Once a day | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 4.17 | 0.550 | 2 | 1 | 3.39 | 2.22 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 4.17 | 0.550 | 2 | 1 | 3.39 | 2.22 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 2 | 6 | 6.25 | 8.33 | 1.000 | 5 | 3 | 8.47 | 6.67 | 1.000 | |||

| Rarely/never | 28 | 56 | 87.50 | 77.78 | 0.290 | 46 | 38 | 77.97 | 84.44 | 0.460 | |||

| Natural juices (squeezed from fruit or purchased without added sugar, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 3 | 9 | 9.38 | 12.50 | 0.750 | 0.940 | 4 | 8 | 6.78 | 17.78 | 0.121 | 0.485 |

| Once a day | 4 | 9 | 12.50 | 12.50 | 1.000 | 8 | 5 | 13.56 | 11.11 | 0.773 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 3 | 7 | 9.38 | 9.72 | 1.000 | 5 | 5 | 8.47 | 11.11 | 0.743 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 6 | 17 | 18.75 | 23.61 | 0.800 | 14 | 9 | 23.73 | 20.00 | 0.812 | |||

| Rarely/never | 16 | 30 | 50.00 | 41.67 | 0.520 | 28 | 18 | 47.46 | 40.00 | 0.551 | |||

| Tea | Two or more times a day | 4 | 5 | 12.50 | 6.94 | 0.620 | 0.323 | 4 | 5 | 6.78 | 11.11 | 0.496 | 0.557 |

| Once a day | 3 | 3 | 9.38 | 4.17 | 0.545 | 2 | 4 | 3.39 | 8.89 | 0.399 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 3 | 9 | 9.38 | 12.50 | 1.000 | 6 | 6 | 10.17 | 13.33 | 0.759 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 5 | 5 | 15.63 | 6.94 | 0.650 | 7 | 3 | 11.86 | 6.67 | 0.509 | |||

| Rarely/never | 17 | 50 | 53.13 | 69.44 | 0.566 | 40 | 27 | 67.80 | 60.00 | 0.418 | |||

| Water | Two or more times a day | 28 | 54 | 87.50 | 75.00 | 0.739 | 0.164 | 50 | 32 | 84.75 | 71.11 | 0.145 | 0.006 |

| Once a day | 0 | 6 | 0.00 | 8.33 | 0.455 | 5 | 1 | 8.47 | 2.22 | 0.231 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 4.17 | 1.000 | 2 | 1 | 3.39 | 2.22 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 2 | 1 | 6.25 | 1.39 | 0.400 | 1 | 2 | 1.69 | 4.44 | 0.577 | |||

| Rarely/never | 2 | 8 | 6.25 | 11.11 | 0.628 | 1 | 9 | 1.69 | 20.00 | 0.002 | |||

| Question | Mother’s Level of Education | Father’s Level of Education | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How Often Does Your Child with Down Syndrome Consume | Frequency of Consumption | HS (n = 55) | UD (n = 49) | HS (%) | UD (%) | p | p Global | HS (n = 72) | UD (n = 32) | HS (%) | UD (%) | p | p Global |

| White/semi-white bread | Two or more times a day | 12 | 8 | 21.82 | 16.33 | 0.619 | 0.105 | 13 | 7 | 18.06 | 21.88 | 0.788 | 0.482 |

| Once a day | 17 | 6 | 30.91 | 12.24 | 0.032 | 18 | 5 | 25.00 | 15.63 | 0.321 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 3 | 6 | 5.45 | 12.24 | 0.301 | 8 | 1 | 11.11 | 3.13 | 0.269 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 6 | 9 | 10.91 | 18.37 | 0.403 | 9 | 6 | 12.50 | 18.75 | 0.546 | |||

| Rarely/never | 17 | 20 | 30.91 | 40.82 | 0.312 | 24 | 13 | 33.33 | 40.63 | 0.511 | |||

| Black/wholemeal bread | Two or more times a day | 4 | 2 | 7.27 | 4.08 | 0.681 | 0.631 | 6 | 0 | 8.33 | 0.00 | 0.174 | 0.575 |

| Once a day | 6 | 4 | 10.91 | 8.16 | 0.746 | 7 | 3 | 9.72 | 9.38 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 3 | 4 | 5.45 | 8.16 | 0.704 | 5 | 2 | 6.94 | 6.25 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 6 | 10 | 10.91 | 20.41 | 0.276 | 10 | 6 | 13.89 | 18.75 | 0.562 | |||

| Rarely/never | 36 | 29 | 65.45 | 59.18 | 0.548 | 44 | 21 | 61.11 | 65.63 | 0.827 | |||

| Whole grains such as barley, oats, etc., in the form of grains, groats, or flour | Two or more times a day | 5 | 5 | 9.09 | 10.20 | 1.000 | 0.882 | 7 | 3 | 9.72 | 9.38 | 1.000 | 0.691 |

| Once a day | 14 | 14 | 25.45 | 28.57 | 0.826 | 21 | 7 | 29.17 | 21.88 | 0.483 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 3 | 5 | 5.45 | 10.20 | 0.471 | 4 | 4 | 5.56 | 12.50 | 0.247 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 13 | 10 | 23.64 | 20.41 | 0.814 | 17 | 6 | 23.61 | 18.75 | 0.798 | |||

| Rarely/never | 20 | 15 | 36.36 | 30.61 | 0.678 | 23 | 12 | 31.94 | 37.50 | 0.655 | |||

| Potatoes | Two or more times a day | 2 | 1 | 3.64 | 2.04 | 1.000 | 0.125 | 3 | 0 | 4.17 | 0.00 | 0.551 | 0.216 |

| Once a day | 3 | 0 | 5.45 | 0.00 | 0.245 | 3 | 0 | 4.17 | 0.00 | 0.551 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 5 | 2 | 9.09 | 4.08 | 0.443 | 4 | 3 | 5.56 | 9.38 | 0.673 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 37 | 43 | 67.27 | 87.76 | 0.019 | 52 | 28 | 72.22 | 87.50 | 0.130 | |||

| Rarely/never | 8 | 3 | 14.55 | 6.12 | 0.210 | 10 | 1 | 13.89 | 3.13 | 0.166 | |||

| Pasta | Two or more times a day | 1 | 1 | 1.82 | 2.04 | 1.000 | 0.467 | 2 | 0 | 2.78 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.561 |

| Once a day | 2 | 0 | 3.64 | 0.00 | 0.497 | 2 | 0 | 2.78 | 0.00 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 2 | 1.82 | 4.08 | 0.600 | 1 | 2 | 1.39 | 6.25 | 0.223 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 42 | 33 | 76.36 | 67.35 | 0.382 | 52 | 23 | 72.22 | 71.88 | 1.000 | |||

| Rarely/never | 9 | 13 | 16.36 | 26.53 | 0.236 | 15 | 7 | 20.83 | 21.88 | 1.000 | |||

| Rice | Two or more times a day | 2 | 1 | 3.64 | 2.04 | 1.000 | 0.261 | 3 | 0 | 4.17 | 0.00 | 0.551 | 0.519 |

| Once a day | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 6.12 | 0.101 | 2 | 1 | 2.78 | 3.13 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | |||

| Once or twice a week | 39 | 36 | 70.91 | 73.47 | 0.829 | 49 | 26 | 68.06 | 81.25 | 0.236 | |||

| Rarely/never | 14 | 9 | 25.45 | 18.37 | 0.480 | 18 | 5 | 25.00 | 15.63 | 0.321 | |||

| Milk | Two or more times a day | 12 | 4 | 21.82 | 8.16 | 0.062 | 0.063 | 16 | 0 | 22.22 | 0.00 | 0.002 | 0.009 |

| Once a day | 14 | 8 | 25.45 | 16.33 | 0.337 | 16 | 6 | 22.22 | 18.75 | 0.798 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 4 | 11 | 7.27 | 22.45 | 0.048 | 8 | 7 | 11.11 | 21.88 | 0.224 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 7 | 6 | 12.73 | 12.24 | 1.000 | 10 | 3 | 13.89 | 9.38 | 0.750 | |||

| Rarely/never | 18 | 20 | 32.73 | 40.82 | 0.421 | 22 | 16 | 30.56 | 50.00 | 0.078 | |||

| Fermented dairy products (yogurt, cream, kefir, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 8 | 2 | 14.55 | 4.08 | 0.098 | 0.067 | 8 | 2 | 11.11 | 6.25 | 0.720 | 0.947 |

| Once a day | 16 | 9 | 29.09 | 18.37 | 0.253 | 18 | 7 | 25.00 | 21.88 | 0.808 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 13 | 11 | 23.64 | 22.45 | 1.000 | 16 | 8 | 22.22 | 25.00 | 0.803 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 7 | 16 | 12.73 | 32.65 | 0.018 | 15 | 8 | 20.83 | 25.00 | 0.620 | |||

| Rarely/never | 11 | 11 | 20.00 | 22.45 | 0.813 | 15 | 7 | 20.83 | 21.88 | 1.000 | |||

| Cheese | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.625 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.345 |

| Once a day | 6 | 2 | 10.91 | 4.08 | 0.276 | 5 | 3 | 6.94 | 9.38 | 0.699 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 4 | 5 | 7.27 | 10.20 | 0.732 | 4 | 5 | 5.56 | 15.63 | 0.129 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 21 | 20 | 38.18 | 40.82 | 0.842 | 29 | 12 | 40.28 | 37.50 | 0.831 | |||

| Rarely/never | 24 | 22 | 43.64 | 44.90 | 1.000 | 34 | 12 | 47.22 | 37.50 | 0.398 | |||

| Fruit | Two or more times a day | 14 | 15 | 25.45 | 30.61 | 0.663 | 0.587 | 20 | 9 | 27.78 | 28.13 | 1.000 | 0.625 |

| Once a day | 21 | 19 | 38.18 | 38.78 | 1.000 | 30 | 10 | 41.67 | 31.25 | 0.385 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 10 | 8 | 18.18 | 16.33 | 1.000 | 11 | 7 | 15.28 | 21.88 | 0.413 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 8 | 3 | 14.55 | 6.12 | 0.210 | 7 | 4 | 9.72 | 12.50 | 0.734 | |||

| Rarely/never | 2 | 4 | 3.64 | 8.16 | 0.417 | 4 | 2 | 5.56 | 6.25 | 1.000 | |||

| Vegetables | Two or more times a day | 6 | 11 | 10.91 | 22.45 | 0.183 | 0.031 | 11 | 6 | 15.28 | 18.75 | 0.78 | 0.207 |

| Once a day | 21 | 20 | 38.18 | 40.82 | 0.842 | 28 | 13 | 38.89 | 40.63 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 12 | 15 | 21.82 | 30.61 | 0.373 | 16 | 11 | 22.22 | 34.38 | 0.362 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 9 | 2 | 16.36 | 4.08 | 0.056 | 9 | 2 | 12.50 | 6.25 | 0.503 | |||

| Rarely/never | 7 | 1 | 12.73 | 2.04 | 0.063 | 8 | 0 | 11.11 | 0.00 | 0.102 | |||

| Meat | Two or more times a day | 4 | 4 | 7.27 | 8.16 | 1.000 | 0.025 | 4 | 4 | 5.56 | 12.50 | 0.267 | 0.119 |

| Once a day | 13 | 14 | 23.64 | 28.57 | 0.656 | 19 | 8 | 26.39 | 25.00 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 16 | 25 | 29.09 | 51.02 | 0.028 | 25 | 16 | 34.72 | 50.00 | 0.433 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 16 | 5 | 29.09 | 10.20 | 0.026 | 17 | 4 | 23.61 | 12.50 | 0.428 | |||

| Rarely/never | 6 | 1 | 10.91 | 2.04 | 0.117 | 7 | 0 | 9.72 | 0.00 | 0.190 | |||

| Meat products (salami, hot dogs, pâté, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 2 | 2 | 3.64 | 4.08 | 1.000 | 0.008 | 1 | 3 | 1.39 | 9.38 | 0.099 | 0.046 |

| Once a day | 6 | 3 | 10.91 | 6.12 | 0.495 | 9 | 0 | 12.50 | 0.00 | 0.059 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 11 | 1 | 20.00 | 2.04 | 0.005 | 10 | 2 | 13.89 | 6.25 | 0.505 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 16 | 11 | 29.09 | 22.45 | 0.506 | 17 | 10 | 23.61 | 31.25 | 0.644 | |||

| Rarely/never | 20 | 32 | 36.36 | 65.31 | 0.006 | 35 | 17 | 48.61 | 53.13 | 0.856 | |||

| Eggs | Two or more times a day | 1 | 1 | 1.82 | 2.04 | 1.000 | 0.298 | 2 | 0 | 2.78 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.417 |

| Once a day | 3 | 2 | 5.45 | 4.08 | 1.000 | 2 | 3 | 2.78 | 9.38 | 0.325 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 2 | 7 | 3.64 | 14.29 | 0.080 | 5 | 4 | 6.94 | 12.50 | 0.463 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 27 | 25 | 49.09 | 51.02 | 1.000 | 38 | 14 | 52.78 | 43.75 | 0.711 | |||

| Rarely/never | 22 | 14 | 40.00 | 28.57 | 0.302 | 25 | 11 | 34.72 | 34.38 | 1.000 | |||

| Fish | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.359 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.172 |

| Once a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 2 | 1.82 | 4.08 | 0.628 | 1 | 2 | 1.39 | 6.25 | 0.236 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 26 | 29 | 47.27 | 59.18 | 0.529 | 36 | 19 | 50.00 | 59.38 | 0.721 | |||

| Rarely/never | 28 | 18 | 50.91 | 36.73 | 0.372 | 35 | 11 | 48.61 | 34.38 | 0.439 | |||

| Olive oil | Two or more times a day | 3 | 4 | 5.45 | 8.16 | 0.704 | 0.003 | 3 | 4 | 4.17 | 12.50 | 0.211 | 0.039 |

| Once a day | 9 | 9 | 16.36 | 18.37 | 0.801 | 11 | 7 | 15.28 | 21.88 | 0.586 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 3 | 13 | 5.45 | 26.53 | 0.005 | 9 | 7 | 12.50 | 21.88 | 0.390 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 6 | 9 | 10.91 | 18.37 | 0.403 | 9 | 6 | 12.50 | 18.75 | 0.556 | |||

| Rarely/never | 34 | 14 | 61.82 | 28.57 | 0.0008 | 40 | 8 | 55.56 | 25.00 | 0.076 | |||

| Coconut oil | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.210 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.014 |

| Once a day | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 2.04 | 0.471 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 3.13 | 0.314 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 4.08 | 0.22 | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 6.25 | 0.101 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 3 | 5 | 5.45 | 10.20 | 0.471 | 4 | 4 | 5.56 | 12.50 | 0.267 | |||

| Rarely/never | 52 | 41 | 94.55 | 83.67 | 0.109 | 68 | 25 | 94.44 | 78.13 | 0.637 | |||

| Refined oils and saturated fats (sunflower oil, canola oil, lard, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 1 | 1 | 1.82 | 2.04 | 1.000 | 0.623 | 1 | 1 | 1.39 | 3.13 | 0.528 | 0.736 |

| Once a day | 6 | 9 | 10.91 | 18.37 | 0.403 | 9 | 6 | 12.50 | 18.75 | 0.556 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 12 | 6 | 21.82 | 12.24 | 0.299 | 13 | 5 | 18.06 | 15.63 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 15 | 12 | 27.27 | 24.49 | 0.825 | 18 | 9 | 25.00 | 28.13 | 0.818 | |||

| Rarely/never | 21 | 21 | 38.18 | 42.86 | 0.691 | 31 | 11 | 43.06 | 34.38 | 0.69 | |||

| Butter | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.507 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.051 |

| Once a day | 3 | 3 | 5.45 | 6.12 | 1.000 | 3 | 3 | 4.17 | 9.38 | 0.38 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 3 | 7 | 5.45 | 14.29 | 0.185 | 4 | 6 | 5.56 | 18.75 | 0.081 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 16 | 13 | 29.09 | 26.53 | 0.829 | 19 | 10 | 26.39 | 31.25 | 0.822 | |||

| Rarely/never | 33 | 26 | 60.00 | 53.06 | 0.554 | 46 | 13 | 63.89 | 40.63 | 0.276 | |||

| Fast food (burgers, pizza, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 1 | 0 | 1.82 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.492 | 1 | 0 | 1.39 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.923 |

| Once a day | 1 | 0 | 1.82 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 1.39 | 0.00 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 0 | 1.82 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 1.39 | 0.00 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 10 | 6 | 18.18 | 12.24 | 0.43 | 12 | 4 | 16.67 | 12.50 | 0.774 | |||

| Rarely/never | 42 | 43 | 76.36 | 87.76 | 0.203 | 57 | 28 | 79.17 | 87.50 | 0.756 | |||

| Sweets (biscuits, cakes, chocolate, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 3 | 0 | 5.45 | 0.00 | 0.245 | 0.159 | 2 | 1 | 2.78 | 3.13 | 1.000 | 0.304 |

| Once a day | 10 | 5 | 18.18 | 10.20 | 0.278 | 11 | 4 | 15.28 | 12.50 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 8 | 6 | 14.55 | 12.24 | 0.781 | 8 | 6 | 11.11 | 18.75 | 0.353 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 20 | 16 | 36.36 | 32.65 | 0.837 | 29 | 7 | 40.28 | 21.88 | 0.078 | |||

| Rarely/never | 14 | 22 | 25.45 | 44.90 | 0.042 | 22 | 14 | 30.56 | 43.75 | 0.264 | |||

| Salty snacks (crackers, pretzels, chips, flips, popcorn, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 6 | 0 | 10.91 | 0.00 | 0.028 | 0.040 | 5 | 1 | 6.94 | 3.13 | 0.664 | 0.318 |

| Once a day | 11 | 4 | 20.00 | 8.16 | 0.101 | 11 | 4 | 15.28 | 12.50 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 6 | 6 | 10.91 | 12.24 | 1.000 | 11 | 1 | 15.28 | 3.13 | 0.099 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 16 | 20 | 29.09 | 40.82 | 0.223 | 24 | 12 | 33.33 | 37.50 | 0.824 | |||

| Rarely/never | 16 | 19 | 29.09 | 38.78 | 0.306 | 21 | 14 | 29.17 | 43.75 | 0.179 | |||

| Nuts (walnuts, almonds, hazelnuts, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.090 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.375 |

| Once a day | 4 | 6 | 7.27 | 12.24 | 0.511 | 5 | 5 | 6.94 | 15.63 | 0.277 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 2.04 | 0.471 | 1 | 0 | 1.39 | 0.00 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 14 | 20 | 25.45 | 40.82 | 0.142 | 23 | 11 | 31.94 | 34.38 | 0.824 | |||

| Rarely/never | 37 | 22 | 67.27 | 44.90 | 0.029 | 43 | 16 | 59.72 | 50.00 | 0.396 | |||

| Seeds (chia, pumpkin, flax, sesame, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 2.04 | 0.471 | 0.562 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 3.13 | 0.308 | 0.465 |

| Once a day | 4 | 5 | 7.27 | 10.20 | 0.732 | 8 | 1 | 11.11 | 3.13 | 0.269 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 3 | 4 | 5.45 | 8.16 | 0.704 | 5 | 2 | 6.94 | 6.25 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 11 | 13 | 20.00 | 26.53 | 0.489 | 16 | 8 | 22.22 | 25.00 | 0.803 | |||

| Rarely/never | 37 | 26 | 67.27 | 53.06 | 0.162 | 43 | 20 | 59.72 | 62.50 | 0.831 | |||

| Carbonated drinks and syrups | Two or more times a day | 4 | 2 | 7.27 | 4.08 | 0.681 | 0.713 | 4 | 2 | 5.56 | 6.25 | 1.000 | 0.981 |

| Once a day | 1 | 2 | 1.82 | 4.08 | 0.300 | 2 | 1 | 2.78 | 3.13 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 2 | 1.82 | 4.08 | 0.600 | 2 | 1 | 2.78 | 3.13 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 3 | 5 | 5.45 | 10.20 | 0.471 | 5 | 3 | 6.94 | 9.38 | 0.699 | |||

| Rarely/never | 46 | 38 | 83.64 | 77.55 | 0.464 | 59 | 25 | 81.94 | 78.13 | 0.788 | |||

| Natural juices (squeezed from fruit or purchased without added sugar, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 8 | 4 | 14.55 | 8.16 | 0.369 | 0.223 | 7 | 5 | 9.72 | 15.63 | 0.507 | 0.837 |

| Once a day | 7 | 6 | 12.73 | 12.24 | 1.000 | 9 | 4 | 12.50 | 12.50 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 8 | 2 | 14.55 | 4.08 | 0.098 | 7 | 3 | 9.72 | 9.38 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 9 | 14 | 16.36 | 28.57 | 0.160 | 15 | 8 | 20.83 | 25.00 | 0.62 | |||

| Rarely/never | 23 | 23 | 41.82 | 46.94 | 0.693 | 34 | 12 | 47.22 | 37.50 | 0.398 | |||

| Tea | Two or more times a day | 7 | 2 | 12.73 | 4.08 | 0.167 | 0.448 | 8 | 1 | 11.11 | 3.13 | 0.269 | 0.700 |

| Once a day | 4 | 2 | 7.27 | 4.08 | 0.681 | 4 | 2 | 5.56 | 6.25 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 7 | 5 | 12.73 | 10.20 | 0.765 | 9 | 3 | 12.50 | 9.38 | 0.751 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 4 | 6 | 7.27 | 12.24 | 0.511 | 6 | 4 | 8.33 | 12.50 | 0.493 | |||

| Rarely/never | 33 | 34 | 60.00 | 69.39 | 0.412 | 45 | 22 | 62.50 | 68.75 | 0.658 | |||

| Water | Two or more times a day | 39 | 43 | 70.91 | 87.76 | 0.053 | 0.259 | 55 | 27 | 76.39 | 84.38 | 0.442 | 0.261 |

| Once a day | 4 | 2 | 7.27 | 4.08 | 0.681 | 4 | 2 | 5.56 | 6.25 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 2 | 1 | 3.64 | 2.04 | 1.000 | 1 | 2 | 1.39 | 6.25 | 0.223 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 3 | 0 | 5.45 | 0.00 | 0.245 | 3 | 0 | 4.17 | 0.00 | 0.551 | |||

| Rarely/never | 7 | 3 | 12.73 | 6.12 | 0.328 | 9 | 1 | 12.50 | 3.13 | 0.169 | |||

| Question | Mother’s Employment Status | Share of Food Costs in Family Income | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How Often Does Your Child with Down Syndrome Consume | Frequency of Consumption | UE (n = 39) | E (n = 65) | UE (%) | E (%) | p | p Global | >50% (n = 35) | <50% (n = 69) | >50% (%) | <50% (%) | p | p Global |

| White/semi-white bread | Two or more times a day | 13 | 7 | 33.33 | 10.77 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 11 | 9 | 31.43 | 13.04 | 0.035 | 0.255 |

| Once a day | 10 | 13 | 25.64 | 20.00 | 0.626 | 8 | 15 | 22.86 | 21.74 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 2 | 7 | 5.13 | 10.77 | 0.478 | 2 | 7 | 5.71 | 10.14 | 0.714 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 1 | 14 | 2.56 | 21.54 | 0.008 | 4 | 11 | 11.43 | 15.94 | 0.769 | |||

| Rarely/never | 13 | 24 | 33.33 | 36.92 | 0.833 | 10 | 27 | 28.57 | 39.13 | 0.386 | |||

| Black/wholemeal bread | Two or more times a day | 3 | 3 | 7.69 | 4.62 | 0.669 | 0.602 | 3 | 3 | 8.57 | 4.35 | 0.402 | 0.192 |

| Once a day | 3 | 7 | 7.69 | 10.77 | 0.740 | 2 | 8 | 5.71 | 11.59 | 0.489 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 6 | 2.56 | 9.23 | 0.252 | 2 | 5 | 5.71 | 7.25 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 5 | 11 | 12.82 | 16.92 | 0.780 | 2 | 14 | 5.71 | 20.29 | 0.082 | |||

| Rarely/never | 27 | 38 | 69.23 | 58.46 | 0.302 | 26 | 39 | 74.29 | 56.52 | 0.090 | |||

| Whole grains such as barley, oats, etc., in the form of grains, groats, or flour | Two or more times a day | 4 | 6 | 10.26 | 9.23 | 1.000 | 0.646 | 3 | 7 | 8.57 | 10.14 | 1.000 | 0.155 |

| Once a day | 12 | 16 | 30.77 | 24.62 | 0.503 | 11 | 17 | 31.43 | 24.64 | 0.489 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 7 | 2.56 | 10.77 | 0.253 | 0 | 8 | 0.00 | 11.59 | 0.049 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 8 | 15 | 20.51 | 23.08 | 0.812 | 6 | 17 | 17.14 | 24.64 | 0.460 | |||

| Rarely/never | 14 | 21 | 35.90 | 32.31 | 0.831 | 15 | 20 | 42.86 | 28.99 | 0.190 | |||

| Potatoes | Two or more times a day | 3 | 0 | 7.69 | 0.00 | 0.050 | 0.019 | 1 | 2 | 2.86 | 2.90 | 1.000 | 0.479 |

| Once a day | 2 | 1 | 5.13 | 1.54 | 0.555 | 2 | 1 | 5.71 | 1.45 | 0.261 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 4 | 3 | 10.26 | 4.62 | 0.421 | 3 | 4 | 8.57 | 5.80 | 0.685 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 24 | 56 | 61.54 | 86.15 | 0.007 | 24 | 56 | 68.57 | 81.16 | 0.217 | |||

| Rarely/never | 6 | 5 | 15.38 | 7.69 | 0.323 | 5 | 6 | 14.29 | 8.70 | 0.501 | |||

| Pasta | Two or more times a day | 2 | 0 | 5.13 | 0.00 | 0.138 | 0.093 | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 2.90 | 0.549 | 0.330 |

| Once a day | 1 | 1 | 2.56 | 1.54 | 1.000 | 2 | 0 | 5.71 | 0.00 | 0.111 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 4.62 | 0.290 | 1 | 2 | 2.86 | 2.90 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 25 | 50 | 64.10 | 76.92 | 0.180 | 24 | 51 | 68.57 | 73.91 | 0.645 | |||

| Rarely/never | 11 | 11 | 28.21 | 16.92 | 0.217 | 8 | 14 | 22.86 | 20.29 | 0.802 | |||

| Rice | Two or more times a day | 2 | 1 | 5.13 | 1.54 | 0.554 | 0.085 | 2 | 1 | 5.71 | 1.45 | 0.261 | 0.064 |

| Once a day | 3 | 0 | 7.69 | 0.00 | 0.050 | 2 | 1 | 5.71 | 1.45 | 0.261 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | |||

| Once or twice a week | 26 | 49 | 66.67 | 75.38 | 0.372 | 20 | 55 | 57.14 | 79.71 | 0.021 | |||

| Rarely/never | 8 | 15 | 20.51 | 23.08 | 0.812 | 11 | 12 | 31.43 | 17.39 | 0.134 | |||

| Milk | Two or more times a day | 7 | 9 | 17.95 | 13.85 | 0.586 | 0.972 | 7 | 9 | 20.00 | 13.04 | 0.395 | 0.709 |

| Once a day | 8 | 14 | 20.51 | 21.54 | 1.000 | 9 | 13 | 25.71 | 18.84 | 0.452 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 6 | 9 | 15.38 | 13.85 | 1.000 | 4 | 11 | 11.43 | 15.94 | 0.769 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 5 | 8 | 12.82 | 12.31 | 1.000 | 3 | 10 | 8.57 | 14.49 | 0.536 | |||

| Rarely/never | 13 | 25 | 33.33 | 38.46 | 0.676 | 12 | 26 | 34.29 | 37.68 | 0.831 | |||

| Fermented dairy products (yogurt, cream, kefir, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 8 | 2 | 20.51 | 3.08 | 0.006 | 0.042 | 3 | 7 | 8.57 | 10.14 | 1.000 | 0.255 |

| Once a day | 6 | 19 | 15.38 | 29.23 | 0.155 | 10 | 15 | 28.57 | 21.74 | 0.473 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 9 | 15 | 23.08 | 23.08 | 1.000 | 6 | 18 | 17.14 | 26.09 | 0.338 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 7 | 16 | 17.95 | 24.62 | 0.474 | 5 | 18 | 14.29 | 26.09 | 0.216 | |||

| Rarely/never | 9 | 13 | 23.08 | 20.00 | 0.805 | 11 | 11 | 31.43 | 15.94 | 0.08 | |||

| Cheese | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.366 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.106 |

| Once a day | 4 | 4 | 10.26 | 6.15 | 0.469 | 5 | 3 | 14.29 | 4.35 | 0.115 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 8 | 2.56 | 12.31 | 0.148 | 3 | 6 | 8.57 | 8.70 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 16 | 25 | 41.03 | 38.46 | 0.838 | 9 | 32 | 25.71 | 46.38 | 0.056 | |||

| Rarely/never | 18 | 28 | 46.15 | 43.08 | 0.839 | 18 | 28 | 51.43 | 40.58 | 0.305 | |||

| Fruit | Two or more times a day | 13 | 16 | 33.33 | 24.62 | 0.372 | 0.633 | 10 | 19 | 28.57 | 27.54 | 1.000 | 0.060 |

| Once a day | 12 | 28 | 30.77 | 43.08 | 0.298 | 8 | 32 | 22.86 | 46.38 | 0.032 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 6 | 12 | 15.38 | 18.46 | 0.793 | 7 | 11 | 20.00 | 15.94 | 0.596 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 5 | 6 | 12.82 | 9.23 | 0.743 | 6 | 5 | 17.14 | 7.25 | 0.176 | |||

| Rarely/never | 3 | 3 | 7.69 | 4.62 | 0.669 | 4 | 2 | 11.43 | 2.90 | 0.176 | |||

| Vegetables | Two or more times a day | 6 | 11 | 15.38 | 16.92 | 1.000 | 0.104 | 5 | 12 | 14.29 | 17.39 | 0.785 | 0.308 |

| Once a day | 12 | 29 | 30.77 | 44.62 | 0.214 | 14 | 27 | 40.00 | 39.13 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 9 | 18 | 23.08 | 27.69 | 0.651 | 6 | 21 | 17.14 | 30.43 | 0.164 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 8 | 3 | 20.51 | 4.62 | 0.018 | 6 | 5 | 17.14 | 7.25 | 0.176 | |||

| Rarely/never | 4 | 4 | 10.26 | 6.15 | 0.469 | 4 | 4 | 11.43 | 5.80 | 0.438 | |||

| Meat | Two or more times a day | 5 | 3 | 12.82 | 4.62 | 0.148 | 0.116 | 3 | 5 | 8.57 | 7.25 | 1.000 | 0.002 |

| Once a day | 10 | 17 | 25.64 | 26.15 | 1.000 | 14 | 13 | 40.00 | 18.84 | 0.032 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 11 | 30 | 28.21 | 46.15 | 0.097 | 5 | 36 | 14.29 | 52.17 | 0.002 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 8 | 13 | 20.51 | 20.00 | 1.000 | 8 | 13 | 22.86 | 18.84 | 0.616 | |||

| Rarely/never | 5 | 2 | 12.82 | 3.08 | 0.100 | 5 | 2 | 14.29 | 2.90 | 0.041 | |||

| Meat products (salami, hot dogs, pâté, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 3 | 1 | 7.69 | 1.54 | 0.147 | 0.233 | 2 | 2 | 5.71 | 2.90 | 0.601 | 0.244 |

| Once a day | 3 | 6 | 7.69 | 9.23 | 1.000 | 5 | 4 | 14.29 | 5.80 | 0.16 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 6 | 6 | 15.38 | 9.23 | 0.359 | 6 | 6 | 17.14 | 8.70 | 0.212 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 12 | 15 | 30.77 | 23.08 | 0.489 | 8 | 19 | 22.86 | 27.54 | 0.645 | |||

| Rarely/never | 15 | 37 | 38.46 | 56.92 | 0.105 | 14 | 38 | 40.00 | 55.07 | 0.213 | |||

| Eggs | Two or more times a day | 2 | 0 | 5.13 | 0.00 | 0.138 | 0.020 | 2 | 0 | 5.71 | 0.00 | 0.111 | 0.020 |

| Once a day | 4 | 1 | 10.26 | 1.54 | 0.064 | 3 | 2 | 8.57 | 2.90 | 0.332 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 4 | 5 | 10.26 | 7.69 | 0.725 | 0 | 9 | 0.00 | 13.04 | 0.027 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 13 | 39 | 33.33 | 60.00 | 0.015 | 16 | 36 | 45.71 | 52.17 | 0.678 | |||

| Rarely/never | 16 | 20 | 41.03 | 30.77 | 0.297 | 14 | 22 | 40.00 | 31.88 | 0.513 | |||

| Fish | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.129 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.202 |

| Once a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 2 | 2.56 | 3.08 | 1.000 | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 4.35 | 0.549 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 16 | 39 | 41.03 | 60.00 | 0.070 | 16 | 39 | 45.71 | 56.52 | 0.308 | |||

| Rarely/never | 22 | 24 | 56.41 | 36.92 | 0.067 | 19 | 27 | 54.29 | 39.13 | 0.151 | |||

| Olive oil | Two or more times a day | 0 | 7 | 0.00 | 10.77 | 0.043 | 0.120 | 3 | 4 | 8.57 | 5.80 | 0.685 | 0.858 |

| Once a day | 9 | 9 | 23.08 | 13.85 | 0.286 | 6 | 12 | 17.14 | 17.39 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 4 | 12 | 10.26 | 18.46 | 0.400 | 4 | 12 | 11.43 | 17.39 | 0.569 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 7 | 8 | 17.95 | 12.31 | 0.565 | 4 | 11 | 11.43 | 15.94 | 0.769 | |||

| Rarely/never | 19 | 29 | 48.72 | 44.62 | 0.691 | 18 | 30 | 51.43 | 43.48 | 0.533 | |||

| Coconut oil | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.142 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.555 |

| Once a day | 1 | 0 | 2.56 | 0.00 | 0.375 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.45 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 3.08 | 0.527 | 1 | 1 | 2.86 | 1.45 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 1 | 7 | 2.56 | 10.77 | 0.253 | 1 | 7 | 2.86 | 10.14 | 0.262 | |||

| Rarely/never | 37 | 56 | 94.87 | 86.15 | 0.202 | 33 | 60 | 94.29 | 86.96 | 0.327 | |||

| Refined oils and saturated fats (sunflower oil, canola oil, lard, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 1 | 1 | 2.56 | 1.54 | 1.000 | 0.970 | 1 | 1 | 2.86 | 1.45 | 1.000 | 0.823 |

| Once a day | 6 | 9 | 15.38 | 13.85 | 1.000 | 6 | 9 | 17.14 | 13.04 | 0.568 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 6 | 12 | 15.38 | 18.46 | 0.793 | 6 | 12 | 17.14 | 17.39 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 11 | 16 | 28.21 | 24.62 | 0.818 | 7 | 20 | 20.00 | 28.99 | 0.356 | |||

| Rarely/never | 15 | 27 | 38.46 | 41.54 | 0.838 | 15 | 27 | 42.86 | 39.13 | 0.833 | |||

| Butter | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.017 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.089 |

| Once a day | 3 | 3 | 7.69 | 4.62 | 0.669 | 4 | 2 | 11.43 | 2.90 | 0.176 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 10 | 0.00 | 15.38 | 0.012 | 2 | 8 | 5.71 | 11.59 | 0.489 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 15 | 14 | 38.46 | 21.54 | 0.073 | 6 | 23 | 17.14 | 33.33 | 0.106 | |||

| Rarely/never | 21 | 38 | 53.85 | 58.46 | 0.686 | 23 | 36 | 65.71 | 52.17 | 0.214 | |||

| Fast food (burgers, pizza, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 1 | 0 | 2.56 | 0.00 | 0.375 | 0.420 | 1 | 0 | 2.86 | 0.00 | 0.337 | 0.464 |

| Once a day | 1 | 0 | 2.56 | 0.00 | 0.375 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.45 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.54 | 1.000 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.45 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 5 | 11 | 12.82 | 16.92 | 0.780 | 7 | 9 | 20.00 | 13.04 | 0.395 | |||

| Rarely/never | 32 | 53 | 82.05 | 81.54 | 1.000 | 27 | 58 | 77.14 | 84.06 | 0.427 | |||

| Sweets (biscuits, cakes, chocolate, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 3 | 0 | 7.69 | 0.00 | 0.050 | 0.198 | 1 | 2 | 2.86 | 2.90 | 1.000 | 0.951 |

| Once a day | 6 | 9 | 15.38 | 13.85 | 1.000 | 6 | 9 | 17.14 | 13.04 | 0.568 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 4 | 10 | 10.26 | 15.38 | 0.561 | 4 | 10 | 11.43 | 14.49 | 0.769 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 15 | 21 | 38.46 | 32.31 | 0.531 | 11 | 25 | 31.43 | 36.23 | 0.669 | |||

| Rarely/never | 11 | 25 | 28.21 | 38.46 | 0.395 | 13 | 23 | 37.14 | 33.33 | 0.828 | |||

| Salty snacks (crackers, pretzels, chips, flips, popcorn, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 6 | 0 | 15.38 | 0.00 | 0.002 | 0.016 | 2 | 4 | 5.71 | 5.80 | 1.000 | 0.077 |

| Once a day | 7 | 8 | 17.95 | 12.31 | 0.565 | 9 | 6 | 25.71 | 8.70 | 0.035 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 4 | 8 | 10.26 | 12.31 | 1.000 | 1 | 11 | 2.86 | 15.94 | 0.056 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 10 | 26 | 25.64 | 40.00 | 0.201 | 11 | 25 | 31.43 | 36.23 | 0.669 | |||

| Rarely/never | 12 | 23 | 30.77 | 35.38 | 0.673 | 12 | 23 | 34.29 | 33.33 | 1.000 | |||

| Nuts (walnuts, almonds, hazelnuts, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.014 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a | 0.001 |

| Once a day | 0 | 10 | 0.00 | 15.38 | 0.012 | 1 | 9 | 2.86 | 13.04 | 0.159 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 0 | 2.56 | 0.00 | 0.375 | 1 | 0 | 2.86 | 0.00 | 0.337 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 9 | 25 | 23.08 | 38.46 | 0.132 | 5 | 29 | 14.29 | 42.03 | 0.004 | |||

| Rarely/never | 29 | 30 | 74.36 | 46.15 | 0.008 | 28 | 31 | 80.00 | 44.93 | 0.0008 | |||

| Seeds (chia, pumpkin, flax, sesame, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.54 | 1.000 | 0.204 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.45 | 1.000 | 0.524 |

| Once a day | 5 | 4 | 12.82 | 6.15 | 0.290 | 3 | 6 | 8.57 | 8.70 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 6 | 2.56 | 9.23 | 0.251 | 1 | 6 | 2.86 | 8.70 | 0.419 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 6 | 18 | 15.38 | 27.69 | 0.229 | 6 | 18 | 17.14 | 26.09 | 0.338 | |||

| Rarely/never | 27 | 36 | 69.23 | 55.38 | 0.214 | 25 | 38 | 71.43 | 55.07 | 0.138 | |||

| Carbonated drinks and syrups | Two or more times a day | 3 | 3 | 7.69 | 4.62 | 0.669 | 0.234 | 5 | 1 | 14.29 | 1.45 | 0.016 | 0.078 |

| Once a day | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 4.62 | 0.290 | 2 | 1 | 5.71 | 1.45 | 0.261 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 2 | 1 | 5.13 | 1.54 | 0.555 | 1 | 2 | 2.86 | 2.90 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 5 | 3 | 12.82 | 4.62 | 0.148 | 2 | 6 | 5.71 | 8.70 | 0.714 | |||

| Rarely/never | 29 | 55 | 74.36 | 84.62 | 0.210 | 25 | 59 | 71.43 | 85.51 | 0.114 | |||

| Natural juices (squeezed from fruit, or purchased without added sugar, etc.) | Two or more times a day | 4 | 8 | 10.26 | 12.31 | 1.000 | 0.664 | 4 | 8 | 11.43 | 11.59 | 1.000 | 0.650 |

| Once a day | 5 | 8 | 12.82 | 12.31 | 1.000 | 4 | 9 | 11.43 | 13.04 | 1.000 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 6 | 4 | 15.38 | 6.15 | 0.170 | 2 | 8 | 5.71 | 11.59 | 0.489 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 8 | 15 | 20.51 | 23.08 | 0.812 | 6 | 17 | 17.14 | 24.64 | 0.460 | |||

| Rarely/never | 16 | 30 | 41.03 | 46.15 | 0.685 | 19 | 27 | 54.29 | 39.13 | 0.151 | |||

| Tea | Two or more times a day | 5 | 4 | 12.82 | 6.15 | 0.290 | 0.273 | 3 | 6 | 8.57 | 8.70 | 1.000 | 0.503 |

| Once a day | 3 | 3 | 7.69 | 4.62 | 0.669 | 3 | 3 | 8.57 | 4.35 | 0.402 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 4 | 8 | 10.26 | 12.31 | 1.000 | 4 | 8 | 11.43 | 11.59 | 1.000 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 1 | 9 | 2.56 | 13.85 | 0.086 | 1 | 9 | 2.86 | 13.04 | 0.159 | |||

| Rarely/never | 26 | 41 | 66.67 | 63.08 | 0.833 | 24 | 43 | 68.57 | 62.32 | 0.665 | |||

| Water | Two or more times a day | 28 | 54 | 71.79 | 83.08 | 0.217 | 0.387 | 26 | 56 | 74.29 | 81.16 | 0.452 | 0.058 |

| Once a day | 2 | 4 | 5.13 | 6.15 | 1.000 | 1 | 5 | 2.86 | 7.25 | 0.661 | |||

| Up to five times a week | 1 | 2 | 2.56 | 3.08 | 1.000 | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 4.35 | 0.549 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 2 | 1 | 5.13 | 1.54 | 0.555 | 3 | 0 | 8.57 | 0.00 | 0.036 | |||

| Rarely/never | 6 | 4 | 15.38 | 6.15 | 0.17 | 5 | 5 | 14.29 | 7.25 | 0.298 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ergović Ravančić, M.; Obradović, V.; Vraneković, J. The Connection Between Socioeconomic Factors and Dietary Habits of Children with Down Syndrome in Croatia. Foods 2025, 14, 1910. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111910

Ergović Ravančić M, Obradović V, Vraneković J. The Connection Between Socioeconomic Factors and Dietary Habits of Children with Down Syndrome in Croatia. Foods. 2025; 14(11):1910. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111910

Chicago/Turabian StyleErgović Ravančić, Maja, Valentina Obradović, and Jadranka Vraneković. 2025. "The Connection Between Socioeconomic Factors and Dietary Habits of Children with Down Syndrome in Croatia" Foods 14, no. 11: 1910. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111910

APA StyleErgović Ravančić, M., Obradović, V., & Vraneković, J. (2025). The Connection Between Socioeconomic Factors and Dietary Habits of Children with Down Syndrome in Croatia. Foods, 14(11), 1910. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111910