Strategies for Traceability to Prevent Unauthorised GMOs (Including NGTs) in the EU: State of the Art and Possible Alternative Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodological Approach

3. Traceability Strategies and Their Implementation in Global Supply Chains

3.1. Existing Traceability Systems within Voluntary Sustainability Standards for Globally Traded Agro-Food Products

- “Identity Preserved” ensures the physical separation of the certified raw material from its extraction or agricultural production to the final consumer good, allowing traceability.

- “Segregation” keeps certified and non-certified materials separate, allowing the mixing of compliant materials from different producers.

- “Mass Balance” tracks certified raw material by weight, allowing mixing before separation for accounting.

- “Book & Claim” involves purchasing sustainability certificates based on raw material quantity, without guaranteeing physical traceability. This model helps manufacturers meet procurement goals when direct sourcing is not possible.

- At the outset, the farmer is obliged to meticulously maintain purchase receipts for seeds or relevant inputs, alongside comprehensive records of yields and resale transactions. In most cases, products are endowed with a unique identification number right at the farm level.

- Subsequently, the initial processor or intermediary entity is tasked with documenting vital details, such as the quantity and origin of certified raw materials received. Moreover, in cases of resale, pertinent information including the buyer’s name and address, loading or dispatch/delivery dates, document issuance dates, certificate number, product description and delivered quantity has to be recorded, along with all associated transport documents.

- The verification process is conducted by external auditors hailing from accredited certification bodies who conduct on-site assessments. These audits encompass a comprehensive review of documents in conjunction with physical site visits including plausibility checks, e.g., to ensure that the seed input is consistent with the crop yield. The frequency of the audits and their intervals are specified in the respective standards. Often, standards employ a risk-based approach, wherein regions with an elevated risk of misdeclaration necessitate a higher frequency of audits, as opposed to regions deemed to have a lower risk of misdeclaration.

3.2. Status Quo of Labelling and Traceability of GM Crop Imports to Europe

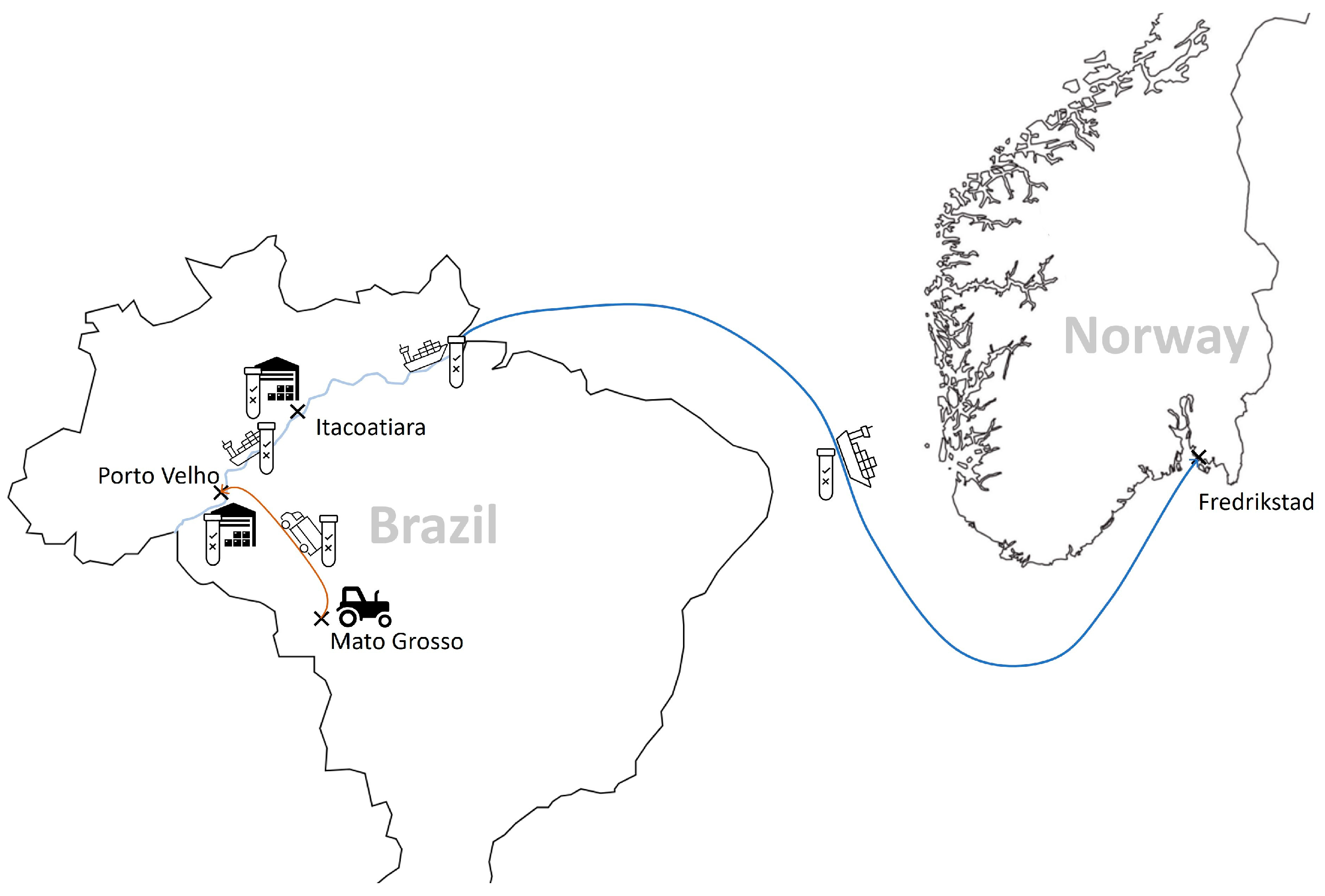

3.3. Traceability of Non-GMO-Labelled Globally Traded Commodities: The Case of Soy from Brazil

3.4. Due-Diligence-Based Regulatory Instruments Contributing to Traceability of Imported Goods

4. Alternative Traceability Strategies to Prevent the Import of Unauthorised GMOs into the EU

4.1. A Risk-Based Approach to Traceability to Prevent the Import of Unauthorised GMOs into the EU—Using Elements of Due Diligence Legal Obligations

4.2. Validation of the Developed Alternative Risk-Based Approach to Prevent the Import of Unauthorised GMOs into the EU

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Questionnaire

| Questions | Relevant Stakeholders |

| All |

| Standard organisations; associations; logistics; businesses; importers |

| Standards; importers, businesses; control laboratories and other stakeholders responsible for spot checks |

| All |

| Non-GMO standards or companies working with isotope analysis; logistics; control laboratories |

| Control laboratories |

| All |

| All |

| All |

References

- European Commission. Directive 2001/18/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 March 2001 on the Deliberate Release into the Environment of Genetically Modified Organisms and Repealing Council Directive 90/220/EEC; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 on Genetically Modified Food and Feed; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) No 1830/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 Concerning the Traceability and Labelling of Genetically Modified Organisms and the Traceability of Food and Feed Products Produced from Genetically Modified Organisms and Amending Directive 2001/18/EC; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ribarits, A.; Narendja, F.; Stepanek, W.; Hochegger, R. Detection Methods Fit-for-Purpose in Enforcement Control of Genetically Modified Plants Produced with Novel Genomic Techniques (NGTs). Agronomy 2021, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 503/2013 of 3 April 2013 on Applications for Authorisation of Genetically Modified Food and Feed in Accordance with REGULATION (EC) No 1829/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Amending Commission Regulations (EC) No 641/2004 and (EC) No 1981/200; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Broothaerts, W.; Jacchia, S.; Angers, A.; Petrillo, M.; Querci, M.; Savini, C.; van den Eede, G.; Emons, H. New Genomic Techniques: State-of-the-Art Review; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; ISBN 9789276246961. [Google Scholar]

- Court of Justice of the European Union. Judgement of the Court (Grand Chamber) of 25 July 2018 in Case C-528/16 Concerning the Request for a Preliminary Ruling under Article 267 TFEU from the Conseil d’État (Council of State, France); European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ribarits, A.; Eckerstorfer, M.; Simon, S.; Stepanek, W. Genome-Edited Plants: Opportunities and Challenges for an Anticipatory Detection and Identification Framework. Foods 2021, 10, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Network of GMO Laboratories. Detection of Food and Feed Plant Products Obtained by New Mutagenesis Techniques; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019; JRC116289. [Google Scholar]

- European Network of GMO Laboratories. Detection of Food and Feed Plant Products Obtained by Targeted Mutagenesis and Cisgenesis; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; ISBN 9789268039342. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Plants Obtained by Certain New Genomic Techniques and Their Food and Feed, and Amending Regulation (EU) 2017/625 COM(2023) 411 Final; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2018/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on Organic Production and Labelling of Organic Products and Repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eckerstorfer, M.F.; Engelhard, M.; Heissenberger, A.; Simon, S.; Teichmann, H. Plants Developed by New Genetic Modification Techniques-Comparison of Existing Regulatory Frameworks in the EU and Non-EU Countries. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. BCH—Biosafety Clearing House. Available online: https://bch.cbd.int/en/ (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- EUginius. The European GMO Database. Available online: https://euginius.eu/euginius/pages/home.jsf (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Parisi, C.; Rodríguez-Cerezo, E. Current and Future Market Applications of New Genomic Techniques; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; ISBN 9789276302063. [Google Scholar]

- Montet, D.; Dey, G. History of Food Traceability. In Food Traceability and Authenticity: Analytical Techniques; Montet, D., Ray, R.C., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 1–30. ISBN 9781351228435. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Sustainable Traceability in the Food Supply Chain: The Impact of Consumer Willingness to Pay. Sustainability 2017, 9, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 Laying down the General Principles and Requirements of Food Law, Establishing the European Food Safety Authority and Laying down Procedures in Matters of Food Safety: (EC) No 178/2002; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- International Trade Centre. Standards Map: The World’s Largest Database for Sustainability Standards. Available online: https://www.standardsmap.org/en/home (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2017/821 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2017 Laying down Supply Chain Due Diligence Obligations for Union Importers of Tin, Tantalum and Tungsten, Their Ores, and Gold Originating from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas: (EU) 2017/821; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes Martins, K.; Teixeira, D.; de Oliveira Corrêa, R. Gains in sustainability using Voluntary Sustainability Standards: A systematic review. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain. 2022, 5, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISEAL Alliance. Chain of Custody Models and Definitions: A Reference Document for Sustainability Standards Systems, and to Complement ISEAL’s Sustainability Claims Good Practice Guide; Cersion 1.0; ISEAL Alliance: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Commandré, Y.; Macombe, C.; Mignon, S. Implications for Agricultural Producers of Using Blockchain for Food Transparency, Study of 4 Food Chains by Cumulative Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, C.; Lillemo, M.; Hvoslef-Eide, T.A.K. Global Regulation of Genetically Modified Crops Amid the Gene Edited Crop Boom—A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 630396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GAIN. Biotechnology and Other New Production Technologies Annual: European Union E42021-0088; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United Nation’s Statistics Division. UN Comtrade Database. Available online: https://comtradeplus.un.org/ (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- ProTerra Foundation. ProTerra Standard: Social Responsibility and Environmental Sustainability. Version 4.1. Available online: https://www.proterrafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ProTerra-Standard-V4.1_EN-2.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Thadani, R.; Rocha, A. Soja não geneticamente modificada no Brasil: A diferenciação interessa ao Produtor? In Proceedings of the XI CASI—Congresso de Administração, Sociedade e Inovação, ECEME, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 6–7 December 2018; Even3: Recife, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leitão, F.O. Análise Sistêmica da Segregação na Cadeia Logística da Soja Após o Advento e a Difusão dos Transgênicos; Universidade de Brasília: Brasilia, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggie, J.G. Business and human rights: The evolving international agenda. Am. J. Int. Law 2007, 101, 819–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggie, J.G. Just Business: Multinational Corporations and Human Rights; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA; London, UK,, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Scherf, C.-S.; Gailhofer, P.; Kampffmeyer, N.; Hilbert, I.; Schleicher, T. Umweltbezogene und Menschenrechtliche Sorgfaltspflichten als Ansatz zur Stärkung Einer Nachhaltigen Unternehmensführung: Zwischenbericht Arbeitspaket 1—Analyse der Genese und des Status quo; TEXTE 102/2019; Umweltbundesamt: Dessau, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kampffmeyer, N.; Gailhofer, P.; Scherf, C.-S.; Schleicher, T.; Westphal, I. Umweltschutz wahrt Menschenrechte! Unternehmen und Politik in der Verantwortung; Öko-Institut Working Paper 3/2018; Öko-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Altenschmidt, S.; Helling, D. Gesetz Über die Unternehmerischen Sorgfaltspflichten zur Vermeidung von Menschenrechtsverletzungen in Lieferketten: Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz—LkSG; Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on the Making Available on the Union Market and the Export from the Union of Certain Commodities and Products Associated with Deforestation and Forest Degradation and Repealing Regulation (EU) No 995/2010: (EU) 2023/1115; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937: CSDDD; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/GuidingprinciplesBusinesshr_eN.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- BDI. EU-Lieferkettengesetz: Entwurf Droht Unternehmen zu Überfordern. Available online: https://bdi.eu/artikel/news/entwurf-droht-unternehmen-zu-ueberfordern (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- DIHK. EU-Lieferkettengesetz Belastet Unternehmen Unverhältnismäßig: DIHK Sieht Auch den Aufbau Resilienterer Wertschöpfungsketten in Gefahr. Available online: https://www.dihk.de/de/aktuelles-und-presse/aktuelle-informationen/eu-lieferkettengesetz-belastet-unternehmen-unverhaeltnismaessig-96298 (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Debevoise & Plimpton; Enodo Rights. Practical Definitions of Cause, Contribute, and Directly Linked to Inform Business Respect for Human Rights: Discussion Draft. 2017. Available online: https://www.business-humanrights.org/sites/default/files/documents/Debevoise-Enodo-Practical-Meaning-of-Involvement-Draft-2017-02-09.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2018).

- Klinger, R.; Krajewski, M.; Krebs, D.; Hartmann, C. Verankerung Menschenrechtlicher Sorgfaltspflichten von Unternehmen im Deutschen Recht; Germanwatch: Bonn, Germany, 2016; ISBN 3943704459. [Google Scholar]

| Stakeholder Type | Number of Interviews |

|---|---|

| European producers of soy-based intermediates for the food and feed industry | 1 |

| Associations (food producers, processing industry) | 3 |

| NGO | 1 |

| Science/research | 1 |

| Voluntary sustainability standard organisations | 2 |

| Authorities | 1 |

| Agricultural trade company | 1 |

| European food manufacturers * | 0 |

| Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) | Bonsucro | Fair Trade USA (APS for Large Farms and Facilities) | Rainforest Alliance—2020 | Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) | Union for Ethical Biotrade (UEBT) | ProTerra Europe | Round Table on Responsible Soy Association—RTRS | Donau Soja Standard | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product/commodity | Cotton, fibres | Sugarcane | Cocoa, coffee, sugarcane, tea | Various (including cocoa, coffee, tea, bananas, palm oil) | Palm oil | Various (including honey, flowers, nuts, spices, sugar, tea) | Raw materials, ingredients or multi-ingredient products of food and feed including soybeans, sugarcane | Soybeans | Soybeans |

| CoCmodelsused | Segregation (farm to ginner) Mass Balance (after ginner level) | Mass balance | Segregation Mass Balance (only allowed for cacao, sugar, tea and fruit juice) | Segregation Mass Balance (only possible for flowers, processed fruits and coconut oil) | Identity Preserved Segregation Mass Balance | Identity Preserved/Segregation (or combination of both) | Segregation Mass Balance (“conventional” or “Country Material Balance”) Book & Claim | Identity Preserved | |

| Dedicated CoC guidelines/ annex | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Non-GMO criteria | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes, core principle | Yes (additional standard) | Yes, core principle, only non-GMO varieties listed in the EU Variety Catalogue or respective national catalogues allowed |

| Input material/seedtraceability criteria | Yes, seed must be traced back to BCI ginnery | Yes, origin matching requirements for cocoa beans and nibs (regional approach possible with few exceptions) | Yes, at least identifying the country of cultivation or wild collection | Yes | Yes, proof of the use of non-GMO seeds (documentation of the entire seed purchase) | Yes, verification of origin based on analytical results. Plausibility check based on risk-based approach | |||

| Documentation requirements | All invoices and shipping documents | Purchase and sales documents linked to physical deliveries of certified, multi-certified and non-certified products. All transactions are recorded | All receipts of RSPO-certified fresh fruit bunches (FFBs) and deliveries of RSPO-certified crude palm oil and palm kernel on a real-time basis | Crop type and volume records (including seed, planted area and plots). Analysis reports. Process, storage, shipment, reception, processing records | All delivery notes and invoices (including lot number and code of certification body) | ||||

| Sampling on representative parts of the operation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Product testing requirements | No | No | No | No | Yes (Immunologically based screening using strip tests and PCR analyses) | Yes, PCR tests at various stages of the value chain (producers, first buyers of the harvest) | Yes, rapid tests, PCR tests and risk-based origin analysis using the Soy Isotope Database | ||

| Identification/labelling requirement | Unique physical identification through batch numbers, labelling or visual and physical identification throughout the supply chain | Physical and visual identification during processing (through lot numbers, record keeping, etc.) | Unique identification number available in all documentation for incoming and outgoing product quantities | Lot numbers linked to traceability information, physical labelling of facilities and conveyances. Unique identification number of received consignments | Lot and quality label “Donau Soja” | ||||

| Digital tools to support traceability | Better Cotton Platform (BCP) for electronic documentation | Online traceability platform | Platform PalmTrace | RTRS Trading Platform | Donau Soya IT database IT-supported batch certification system |

| Article in EU Conflict Minerals Regulation | Content and Relevance for GMO Practice Example |

|---|---|

| Article 1 * | Subject matter and scope—Comprises a clarification of the regulation´s scope and introduction of threshold values for its applicability. Defining a clear scope and introducing threshold values need to be considered for a theoretical transfer to the GMO sector. |

| Article 2 | Definitions—Explains how specific terms used in the regulation shall be understood. Although this is highly relevant for all (real) regulations, it does not add any value at the stage of a theoretical transfer to the GMO sector. |

| Article 3 | Compliance of Union importers with supply chain due diligence obligations—Requests that union importers have to comply with the regulation, assigns responsibility for checks to the competent authorities and introduces the possibility that due diligence schemes might apply for recognition by the European Commission. As the requirements are elaborated in more detail in other Articles, no transfer for the theoretical practice example in the GMO sector is necessary. |

| Article 4 * | Management system obligations—Describes, on a more abstract level, which management systems need to be introduced by importers of conflict minerals into the EU. Some of the rather holistic requirements help to understand the theoretical transfer to the GMO sector. |

| Article 5 * | Risk management obligations—Comprises a more detailed description of how risk identification and assessment should be conducted. A transfer to the GMO example is very important to understand what due diligence efforts could look like in the sector. |

| Article 6 | Third-party audit obligations—Specifies how third-party audits should be carried out. A theoretical transfer to the food sector is not necessary as there are well-established routines that could be used for this purpose. |

| Article 7 | Disclosure obligations—In addition to rather general disclosure requirements, it is specified in more detail how companies must share certain information. As public reporting is also requested in Article 4, a transfer to the GMO sector does not add any additional value. |

| Article 8 * | Recognition of supply chain due diligence schemes—Introduces the possibility of due diligence schemes becoming officially recognised by the European Commission. If schemes are successfully recognised, members are automatically considered compliant. Found to be relevant for a theoretical transfer, as this might be applicable for (existing) non-GMO certifications. |

| Article 9 | List of global responsible smelters and refiners—Description of what the European Commission shall do to provide a list of global responsible smelters and refiners. Relevant for the practical GMO example in order to analyse if there are comparable mechanisms that support companies with the implementation of due diligence. |

| Article 10 | Member state competent authorities—Requirements for how responsible competent authorities shall be assigned with the application for the regulation. These organisational requirements are found to be too detailed for the intended transfer to the GMO sector. |

| Article 11 | Ex post checks on Union importers—Outlines how ex post compliance checks shall be carried out. These requirements are found to be too detailed for the intended transfer for the GMO sector. |

| Article 12 | Records of ex post checks on Union importers—Establishes rules on how ex post checks shall be documented. These requirements are found to be too detailed for the intended transfer for the GMO sector. |

| Article 13 | Cooperation and information exchange—Depicts how competent authorities of Member States shall cooperate and exchange information. These requirements are found to be too detailed for the intended transfer for the GMO sector. |

| Article 14 * | Guidelines—Defines that the European Commission will provide (non-binding) guidelines to support implementation of the regulation by economic operators. This shall include a regularly updated list of conflict-affected and high-risk areas. Relevant for the theoretical practice example, as guidelines for risk evaluation could also facilitate applicability here. |

| Article 15 | Committee procedures—Description of an assistant committee. These requirements are found to be too detailed for the intended transfer for the GMO sector. |

| Article 16 | Rules applicable to infringement—Requirements on how to follow up on non-compliance. These requirements are found to be too detailed for the intended transfer for the GMO sector. |

| Article 17 | Reporting and review—Defines how Member States shall report back to the European Commission. These requirements are found to be too detailed for the intended transfer for the GMO sector. |

| Article 18 | Methodology for calculation of thresholds—Elaborates how threshold values shall be calculated. These requirements are found to be too detailed for the intended transfer for the GMO sector. |

| Article 19 | Exercise of the delegation—Defines under which conditions delegated acts might be adopted. These requirements are found to be too detailed for the intended transfer for the GMO sector. |

| Article 20 | Entry into force and date of application—Specifies when different sections of the regulation will enter into force. These requirements are found to not deliver any additional value for the intended transfer for the GMO sector. |

| Article 1—Subject matter and scope | Practical implications |

| The regulation applies to Union importers of agricultural food and feed materials (raw and pre-processed products). The regulation does not apply to importers below certain (to be defined) threshold values. | FoodAlternatives needs to conduct due diligence for all agricultural products used in its products. Only those agricultural products bought and used in minor quantities below certain threshold values can be exempted |

| Article 4—Management system obligations | Practical implications |

| (4a) Respective importers shall adopt and communicate to suppliers and the public their supply chain policy for their purchased agricultural raw materials. | Prior to the new regulation, FoodAlternatives had published on its website its reasoning and strategy for why and how it was able to obtain its non-GMO products. With the introduction of the new regulation, the company complements the reporting. It now includes various references to the EU regulation and sets out how the different requirements are implemented in practice. The company´s suppliers are already well aware of their non-GMO policy and do not need extra communication. |

| (4b) Importers shall introduce due diligence consistent with OECD due diligence guideline Annex II. | The company reviews the regulation and recognises that it fulfils almost all of the criteria mentioned. Only minor adaptations are necessary—a detailed description of their due diligence activities can be found below under Article 5. |

| (4c) Importers shall assign senior management responsibility to supply chain due diligence. | The company has a senior manager responsible for supply chain management. Her previous responsibilities included setting up appropriate non-GMO supply chains and overseeing the certification process. She is now also responsible for overseeing the due diligence process. |

| (4d) Importers shall incorporate due diligence requirements in contracts and agreements with suppliers (in line with OECD guidance). | The company only buys non-GMO agricultural goods, and its contracts oblige suppliers to deliver only goods with GMO contamination below the current EU threshold. There is no urgent need to adapt current contracts. |

| (4e) Importers shall establish a grievance mechanism, individually or in collaboration with other operators or by facilitating resources for external experts. |

|

| (4f) Importers shall introduce a traceability system for the supply chain. Therefore, they shall document information on the imported food ingredient´s name, name and address of the suppliers, country of origin and imported quantities. | FoodAlternatives has built up non-GMO supply chains over various years. For this purpose, different models are used. For its sugar cane supply, the company directly works together with a cooperative in Colombia. Therefore, the company has an overview of the whole supply chain and all involved actors. |

| (4g) Imported food ingredients must have proof that they do not contain GMOs that are not authorised in the EU. Records of third-party audits have to be provided. If no audits are available, further information on the supply chain has to be shared. | Soy is mainly bought from Brazil. The company has identified and established trade relations with a supplier that offers non-GMO-certified soy. As the used third-party non-GMO certification is accepted under the new due diligence regulation (see Article 8), the company does not need to investigate this soy supply chain itself. Also, for other supply chains that are third-party-certified with a recognised scheme, detailed traceability data are available at the supplier level. In these cases, there is no need for the company to collect data for itself. |

| Article 5—Risk management obligations | Practical implications |

| (5.1a) Importers shall identify and assess the risk of adverse impacts of their supply chain, based on the information collected (see Article 4). | The established non-GMO-certified Brazilian soy supply chain and the non-GMO-certified Colombian sugar cane supply chain are found to not represent increased risks for GMO contamination. However, based on the NGO report (see above), the maize supply chain originating in the USA represents an increased risk. The investigation of the supply chain and especially the involved seed producers does not confirm the possible use of an NGT maize variety. But it reveals an (unintended) contamination risk, as one intermediary trades with GMO and non-GMO maize and does not have strictly separated transport fleets. Therefore, FoodAlternatives decides to investigate further within this supply chain. Systematic laboratory testing over the next months shows regular contamination with known GMO varieties above the EU threshold. |

| (5.1b) Importers shall implement a strategy to respond to identified risks in line with OECD due diligence guidance. (5.2) In this context, mitigating risks does not automatically mean stopping trade in respective regions, but trade might be continued while risk mitigation efforts are implemented at the same time. If trade is continued (or only temporarily suspended), a risk mitigation strategy has to be developed together with concerned stakeholders (government authorities, civil society organisations, affected third parties, etc.). | Based on the identified source of contamination, FoodAlternatives decides to restructure its maize supply chain from the USA. The company is able to identify a supplier that established a completely separate supply chain, including all intermediaries and transport companies. Also, the used seed varieties are disclosed and do not include NGT maize. |

| (5.4) Where available, existing third-party audits might be used as part of the risk mitigation strategy. | FoodAlternatives already uses various raw materials officially certified as non-GMO. Many of them use a certification scheme that is officially recognised by the European Commission (see Article 8). For the respective supply chains, the new regulation does not have any implications for trade relations and documentation requests. As FoodAlternatives is a member of a non-GMO association, it is also able to make use of regularly updated risk evaluations for supply chains from specific countries. The latest risk update confirms a low risk for sugar cane sourced from a specific region in Colombia. As this is in line with the risk evaluation conducted by the European Commission (see Article 9), no third-party audit is necessary. |

| Article 8—Recognition of supply chain due diligence schemes | Practical implications: |

| (8.1) “Scheme owners” can apply to the European Commission to have their due diligence scheme recognised. | FoodAlternatives buys certified non-GMO rapeseed from Ukraine. As the used non-GMO certification is not (yet) recognised by the European Commission, the company needs to document and explain the due diligence efforts taken in this supply chain. As the company knows various European companies are buying rapeseed from the same supplier, it decides to contact the supplier´s management to find out if the supplier would be willing to undergo the process of “official recognition” of the certificate by the European Commission. |

| (8.3) If a scheme is recognised, members fulfilling the requirements of the scheme automatically comply with the EU Conflict Minerals Regulation. | The Ukrainian rapeseed supplier is able to obtain the non-GMO certification officially recognised by the European Commission. In the following years, the company does not need to invest in any additional due diligence efforts for this supply chain. |

| Article 14—Guidelines | Practical implications: |

| (14.1 and 14.2) The Commission assigns external experts to provide an indicative list of high-risk areas of GMO agriculture for each crop. The list can be used as a guide for companies carrying out due diligence. | The European Commission decides to assign external experts to compile an annual overview of agricultural goods imported (in relevant amounts) into the EU. The list contains not only the exporting countries most relevant for European companies, but also an overview of GM varieties available in these countries. It also indicates countries in which GMOs are deregulated and NGT varieties are no longer accounted as GMOs. Looking at the practical implications, a company that already has a good overview of its supply chain and has already incorporated sustainability aspects into its strategy would not require too much additional effort to comply with the proposed alternative risk-based strategy for GMO traceability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teufel, J.; López Hernández, V.; Greiter, A.; Kampffmeyer, N.; Hilbert, I.; Eckerstorfer, M.; Narendja, F.; Heissenberger, A.; Simon, S. Strategies for Traceability to Prevent Unauthorised GMOs (Including NGTs) in the EU: State of the Art and Possible Alternative Approaches. Foods 2024, 13, 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13030369

Teufel J, López Hernández V, Greiter A, Kampffmeyer N, Hilbert I, Eckerstorfer M, Narendja F, Heissenberger A, Simon S. Strategies for Traceability to Prevent Unauthorised GMOs (Including NGTs) in the EU: State of the Art and Possible Alternative Approaches. Foods. 2024; 13(3):369. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13030369

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeufel, Jenny, Viviana López Hernández, Anita Greiter, Nele Kampffmeyer, Inga Hilbert, Michael Eckerstorfer, Frank Narendja, Andreas Heissenberger, and Samson Simon. 2024. "Strategies for Traceability to Prevent Unauthorised GMOs (Including NGTs) in the EU: State of the Art and Possible Alternative Approaches" Foods 13, no. 3: 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13030369

APA StyleTeufel, J., López Hernández, V., Greiter, A., Kampffmeyer, N., Hilbert, I., Eckerstorfer, M., Narendja, F., Heissenberger, A., & Simon, S. (2024). Strategies for Traceability to Prevent Unauthorised GMOs (Including NGTs) in the EU: State of the Art and Possible Alternative Approaches. Foods, 13(3), 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13030369