The Use of Ultraviolet Irradiation to Improve the Efficacy of Acids That Are Generally Recognized as Safe for Disinfecting Fresh Produce in the Ready-to-Eat Stage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Inoculation

2.3. Wash Water Preparation

2.4. Disinfection

2.5. Microbiological Analysis

2.6. Cross-Contamination Incidence Analysis

2.7. Color Analysis

2.8. Analysis of Nutrition Properties

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

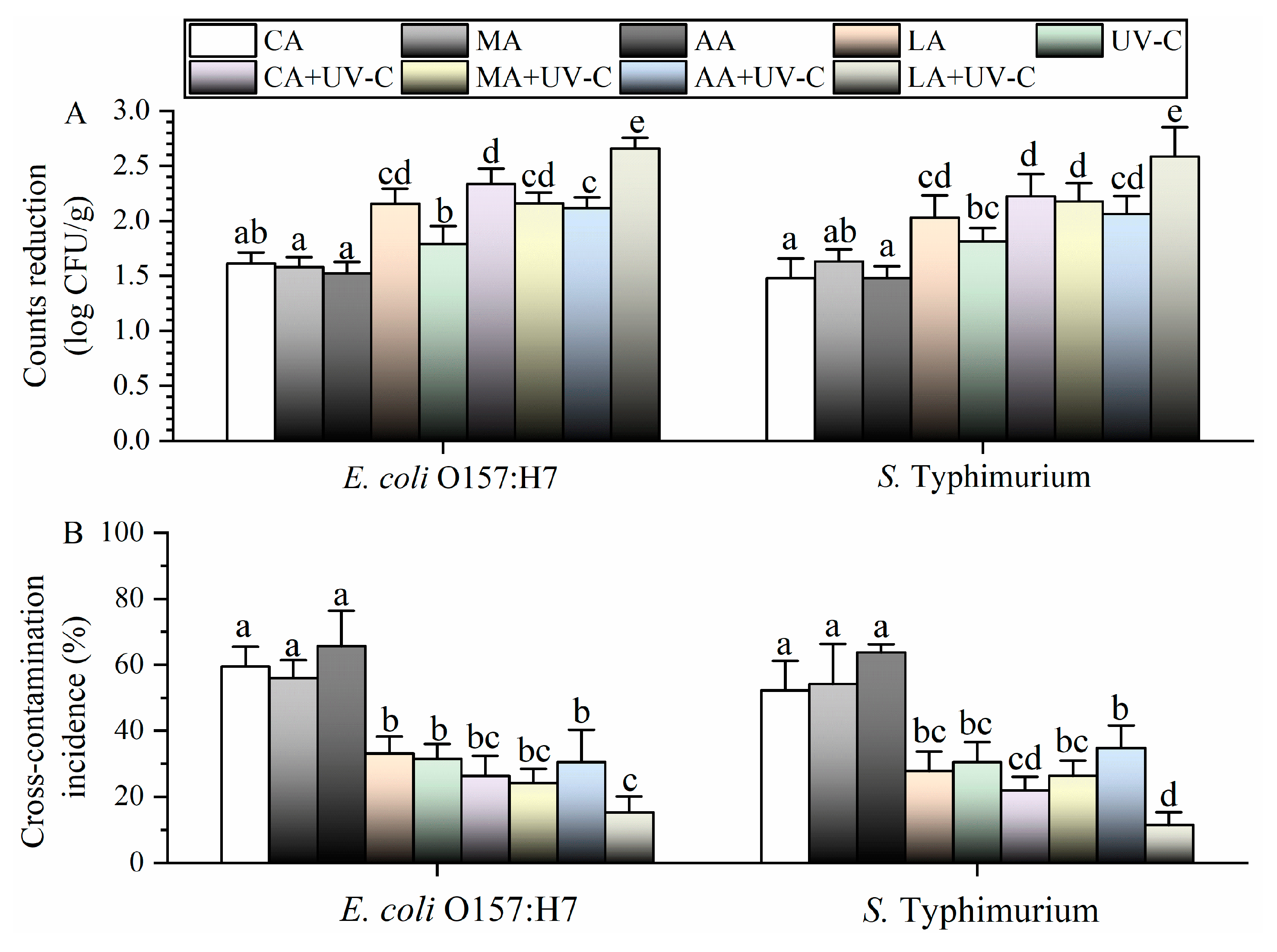

3.1. Effects of Different Treatments against Pathogens on Lettuce

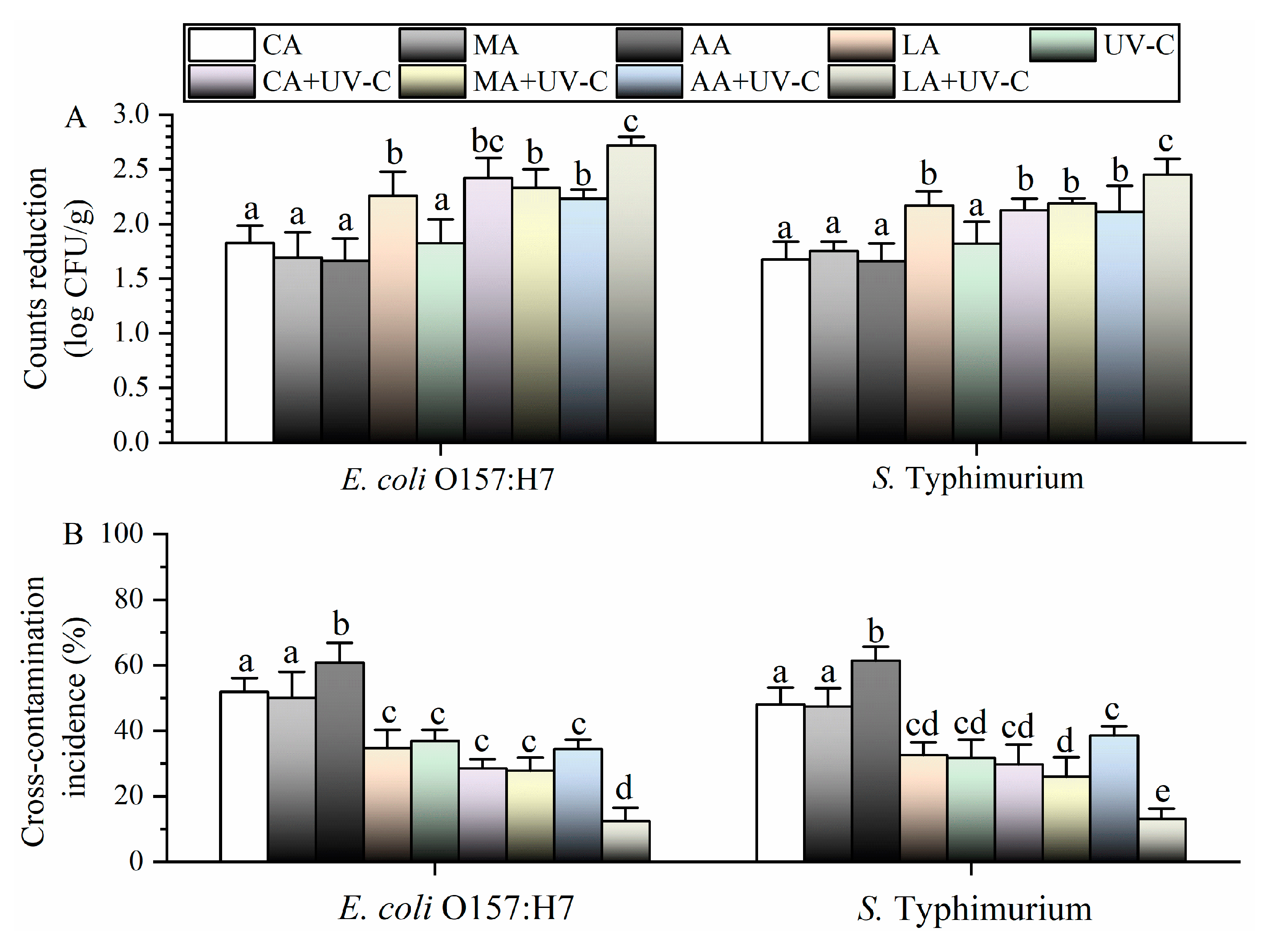

3.2. Effects of Different Treatments against Pathogens on Cherry Tomatoes

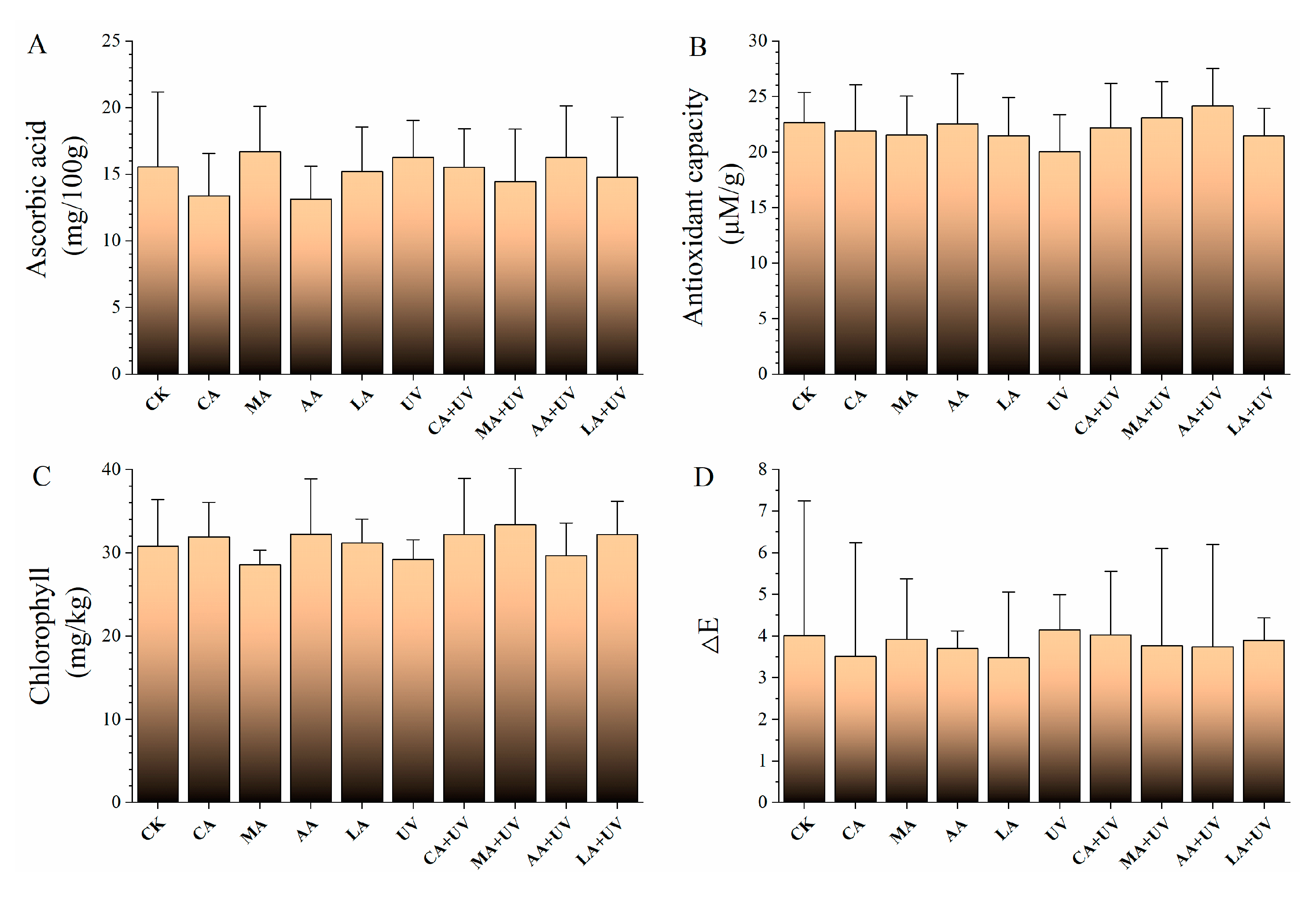

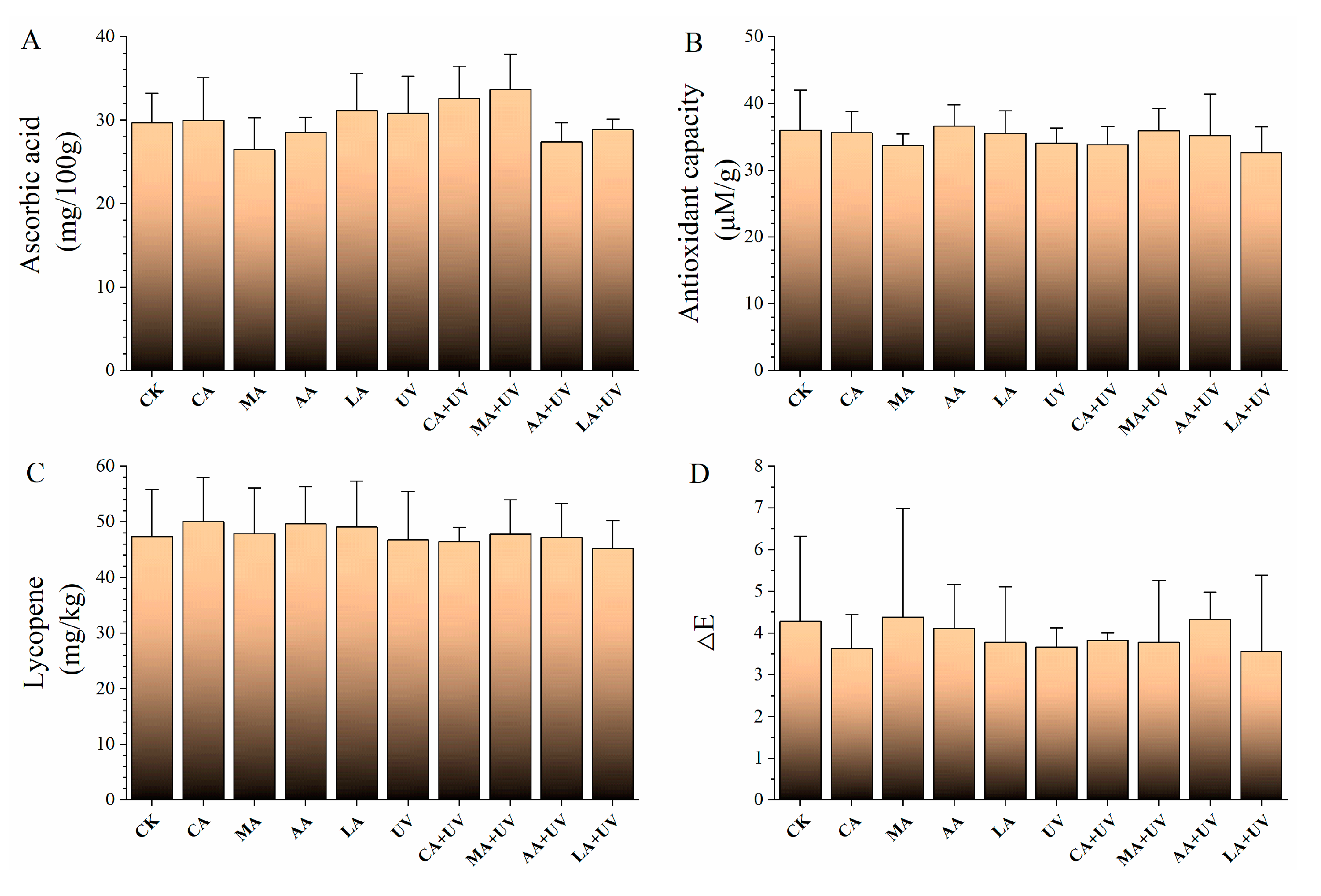

3.3. Effects of Different Treatments on Quality Indicators in Lettuce and Cherry Tomatoes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H. Combination of ozone and ultrasonic-assisted aerosolization sanitizer as a sanitizing process to disinfect fresh-cut lettuce. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 76, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Salmonella Outbreak Linked to Fresh Basil. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/basil-04-24/index.html (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- De Corato, U. Improving the shelf-life and quality of fresh and minimally-processed fruits and vegetables for a modern food industry: A comprehensive critical review from the traditional technologies into the most promising advancements. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 60, 940–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssemanda, J.N.; Joosten, H.; Bagabe, M.C.; Zwietering, M.H.; Reij, M.W. Reduction of microbial counts during kitchen scale washing and sanitization of salad vegetables. Food Control 2018, 85, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombas, D.; Luo, Y.; Brennan, J.; Shergill, G.; Petran, R.; Walsh, R.; Hau, H.; Khurana, K.; Zomorodi, B.; Rosen, J.; et al. Guidelines to validate control of cross-contamination during washing of fresh-cut leafy vegetables. J. Food Prot. 2017, 80, 312–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meireles, A.; Giaouris, E.; Simões, M. Alternative disinfection methods to chlorine for use in the fresh-cut industry. Food Res. Int. 2016, 82, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ölmez, H.; Kretzschmar, U. Potential alternative disinfection methods for organic fresh-cut industry for minimizing water consumption and environmental impact. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finten, G.; Agüero, M.V.; Jagus, R.J. Citric acid as alternative to sodium hypochlorite for washing and disinfection of experimentally-infected spinach leaves. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 82, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Pang, X.; Zhao, X.; Yang, H. Sanitising efficacy of lactic acid combined with low-concentration sodium hypochlorite on Listeria innocua in organic broccoli sprouts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 295, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-H.; Song, K.B. Combined effect of a positively charged cinnamon leaf oil emulsion and organic acid on the inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes inoculated on fresh-cut Treviso leaves. Food Microbiol. 2018, 76, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Villarroel, A.Y.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Soliva-Fortuny, R. Combined effects of malic acid dip and pulsed light treatments on the inactivation of Listeria innocua and Escherichia coli on fresh-cut produce. Food Control 2015, 52, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, W.; Jing, X.; Liu, Y.; Yan, J.; Liu, S.; Qin, W. Combination of calcium lactate impregnation with UV-C irradiation maintains quality and improves antioxidant capacity of fresh-cut kiwifruit slices. Food Chem. X 2022, 14, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Z. Minimal processing of produce using a combination of UV-C irradiation and ultrasound-assisted washing. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 182, 114901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyne, A.L.; Blessington, T.; Williams, T.R.; Koike, S.T.; Harris, L.J.J.F.M. Conditions at the time of inoculation influence survival of attenuated Escherichia coli O157:H7 on field-inoculated lettuce. Food Microbiol. 2019, 85, 103274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, K.; Wu, Z.; Yu, Y. Effects of ultrasound-assisted low-concentration chlorine washing on ready-to-eat winter jujube (Zizyphus jujuba Mill. cv. Dongzao): Cross-contamination prevention, decontamination efficacy, and fruit quality. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 82, 105905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Maimaitiyiming, R.; Aihaiti, A. Comparison of plasma-activated water and free chlorine in disinfecting Escherichia coli O157:H7- and Salmonella Typhimurium-inoculated blueberry, cherry tomato, fresh-cut lettuce, and baby spinach. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 187, 115384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, A.; Koutsoumanis, K.P. Effect of treating lettuce surfaces with acidulants on the behaviour of Listeria monocytogenes during storage at 5 and 20 °C and subsequent exposure to simulated gastric fluid. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 129, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, H. Effect of organic acids, hydrogen peroxide and mild heat on inactivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 on baby spinach. Food Control 2011, 22, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Jeong, S.-G.; Back, K.-H.; Park, K.-H.; Chung, M.-S.; Kang, D.-H. Effect of various conditions on inactivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Listeria monocytogenes in fresh-cut lettuce using ultraviolet radiation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 166, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Dong, Y. Combination of polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride and potassium peroxymonosulfate to disinfect ready-to-eat lettuce. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 40316–40320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; Aihaiti, A.; Maimaitiyiming, R. Pulsed-control plasma-activated water: An emerging technology to assist ultrasound for fresh-cut produce washing. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 102, 106739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tao, D.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Zheng, F.; Wu, Z. Disinfection of lettuce using organic acids: An ecological analysis using 16S rRNA sequencing. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 17514–17520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricke, S.C. Perspectives on the use of organic acids and short chain fatty acids as antimicrobials. Poult. Sci. 2003, 82, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Chang, T.; Yang, H.; Cui, M. Antibacterial mechanism of lactic acid on physiological and morphological properties of Salmonella Enteritidis, Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control 2015, 47, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Tao, D.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Zheng, F.; Wu, Z. Reduction of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, and naturally present microbe counts on lettuce using an acid mixture of acetic and lactic acid. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, Z. Reduction of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and naturally present microbes on fresh-cut lettuce using lactic acid and aqueous ozone. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 22636–22643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Use of aqueous ozone rinsing to improve the disinfection efficacy and shorten the processing time of ultrasound-assisted washing of fresh produce. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 105931, 105931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Z. Combined use of ultrasound-assisted washing with in-package atmospheric cold plasma processing as a novel non-thermal hurdle technology for ready-to-eat blueberry disinfection. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 84, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, H. Effects of potential organic compatible sanitisers on organic and conventional fresh-cut lettuce (Lactuca sativa Var. Crispa L.). Food Control 2017, 72, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-B.; Kang, J.-H.; Song, K.B. Combined treatment of cinnamon bark oil emulsion washing and ultraviolet-C irradiation improves microbial safety of fresh-cut red chard. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 93, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haute, S.; Uyttendaele, M.; Sampers, I. Organic acid based sanitizers and free chlorine to improve the microbial quality and shelf-life of sugar snaps. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 167, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haute, S.; Tryland, I.; Escudero, C.; Vanneste, M.; Sampers, I. Chlorine dioxide as water disinfectant during fresh-cut iceberg lettuce washing: Disinfectant demand, disinfection efficiency, and chlorite formation. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 75, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez-Aguirre, D.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V. Disinfection of selected vegetables under nonthermal treatments: Chlorine, acid citric, ultraviolet light and ozone. Food Control 2013, 29, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poimenidou, S.V.; Bikouli, V.C.; Gardeli, C.; Mitsi, C.; Tarantilis, P.A.; Nychas, G.J.; Skandamis, P.N. Effect of single or combined chemical and natural antimicrobial interventions on Escherichia coli O157:H7, total microbiota and color of packaged spinach and lettuce. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 220, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maimaitiyiming, R.; Yang, Y.; Mulati, A.; Aihaiti, A.; Wang, J. The Use of Ultraviolet Irradiation to Improve the Efficacy of Acids That Are Generally Recognized as Safe for Disinfecting Fresh Produce in the Ready-to-Eat Stage. Foods 2024, 13, 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13111723

Maimaitiyiming R, Yang Y, Mulati A, Aihaiti A, Wang J. The Use of Ultraviolet Irradiation to Improve the Efficacy of Acids That Are Generally Recognized as Safe for Disinfecting Fresh Produce in the Ready-to-Eat Stage. Foods. 2024; 13(11):1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13111723

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaimaitiyiming, Ruxianguli, Yuting Yang, Ailikemu Mulati, Aihemaitijiang Aihaiti, and Jiayi Wang. 2024. "The Use of Ultraviolet Irradiation to Improve the Efficacy of Acids That Are Generally Recognized as Safe for Disinfecting Fresh Produce in the Ready-to-Eat Stage" Foods 13, no. 11: 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13111723

APA StyleMaimaitiyiming, R., Yang, Y., Mulati, A., Aihaiti, A., & Wang, J. (2024). The Use of Ultraviolet Irradiation to Improve the Efficacy of Acids That Are Generally Recognized as Safe for Disinfecting Fresh Produce in the Ready-to-Eat Stage. Foods, 13(11), 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13111723