Abstract

Food insecurity comprises a major global public health threat, as its effects are detrimental to the mental, physical, and social aspects of the health and well-being of those experiencing it. We performed a narrative literature review on the magnitude of global food insecurity with a special emphasis on Greece and analyzed the major factors driving food insecurity, taking into consideration also the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. An electronic search of international literature was conducted in three databases. More than 900 million people worldwide experience severe food insecurity, with future projections showing increasing trends. Within Europe, Eastern and Southern European countries display the highest food insecurity prevalence rates, with Greece reporting a prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity ranging between 6.6% and 8% for the period 2019–2022. Climate change, war, armed conflicts and economic crises are major underlying drivers of food insecurity. Amidst these drivers, the COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on food insecurity levels around the globe, through halting economic growth, disrupting food supply chains and increasing unemployment and poverty. Tackling food insecurity through addressing its key drivers is essential to any progress towards succeeding the Sustainable Development Goal of “Zero Hunger”.

1. Introduction

While we are racing through the fourth industrial revolution of ground-breaking technological and scientific advancements, food insecurity remains an unresolved issue for humankind with profound impact on our societies, health and well-being [1].

Indicatively, according to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) in 2020, one in three people across the globe did not have access to adequate food [1]. Food insecurity refers to (a) the uncertain or limited availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods required for normal human growth and a healthy life and (b) the uncertain or limited ability to access such foods in socially acceptable ways (i.e., not live off charity-based food redistributions). In its broader sense, food insecurity also encompasses the pillars of food use or misuse (i.e., households and individuals must be able to utilize the food in a way that has a positive nutritional impact) [2,3].

Overarching the conditions of malnutrition, undernutrition, undernourishment, hidden hunger (i.e., micronutrient deficiency), hunger and starvation in multifarious contexts (e.g., high/borderline food security settings expressed as chronic, acute or transitory food insecurity) [4], food insecurity comprises a major global public health problem [5], which may affect health in multiple ways, including all three aspects of mental, physical and social well-being. Moreover, food insecurity may have detrimental effects on any life stage, whether in a cyclical continuum form (i.e., from pregnancy to infancy and childhood) or by developmental and life stage per se [6].

Notably, food insecurity, especially during childhood, is linked to increased morbidity and mortality [7,8]. It is estimated that nearly 45% of global child mortality is associated with malnutrition [9], while nearly 66 million children go to school hungry on a daily basis [10]. Amongst an array of detrimental effects in children, food insecurity is associated with suboptimal physical child development, such as stunting, mediated by inadequate food intake, but also increased susceptibility to infections and development of chronic diseases later in life (e.g., cardiovascular disease, obstructive pulmonary disease, cancers, asthma and autoimmune disease, and depression) [8,11]. Furthermore, food insecurity during childhood is associated with reduced learning and productivity, delayed speech development, behavioral problems, and poor social relationships [8]. In addition, childhood hunger is considered a risk factor both for depression and suicidal tendencies in adolescence and young adulthood [12,13].

An additional health concern is the association of food insecurity with obesity among both children and adults [1,14]. While food insecurity is not the generative cause of obesity, the intake of non-nutritious, energy-dense, low-cost foods in conjunction with food insecurity associated stress and downstream physiological adaptations (such as low birthweight and stunting in children) are associated with the occurrence of obesity later in life [14].

Food insecurity largely stems from poverty and economic inequalities at the individual, community and country level [15]. Within this causal context, identifying and analyzing key systemic macro-factors determining and co-driving food insecurity trends and their associated burden in our societies is key to informing and strengthening food security state policies and social actions. Moreover, analyzing the magnitude of food insecurity through a country case-study approach whilst also maintaining a global outlook may raise awareness and support multi-level evidence-based decision making [16].

Taking into consideration the complexity and immediate need for addressing the public health problem of food insecurity and from an advocacy standpoint of the WHO framework ‘’leave no one behind’’, alongside the 2030 interconnected sustainable development goals, ‘’Zero Hunger’’, “Zero Poverty”, “Reduce Inequalities” and ‘’Good Health and Well-being’’ [17], the aims of the current review are to (i) summarize the global magnitude of food insecurity with a special emphasis on Greece, as a developed European country experiencing a profound financial crisis in recent years further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, and (ii) analyze the major macro-factors driving food insecurity taking into consideration also the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially during the pandemic’s acute emergency phase.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Information Sources

For the aims of this narrative review, an electronic search of international literature was conducted in three different databases (PubMeD/MEDLINE® (US National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA), Scopus (Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and Google Scholar (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA) from December 2021 until November 2023. The following keywords and Boolean operators were used in our search: (“food insecurity” OR “food security” OR “food deprivation” OR “malnutrition” OR “undernutrition” OR “undernourishment” OR “micronutrient deficiency” OR “overweight” OR “food waste” OR “hunger” OR “hidden hunger”) AND (“COVID-19 Pandemic” OR “financial crisis” OR “economic crisis” OR “war” OR “armed conflict” OR “climate change” OR “climate/Climatic crisis” OR “environmental degradation”), with or without defining geographic areas of interest (at continent or country level).

In addition, we screened the websites of the World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), World Food Program, UNICEF, Greek Ministry of Health, Hellenic Statistical Authority and other organizations, institutes and institutions for any information referring to food insecurity between 2005 and 2023. Finally, data aggregator and visualization platforms obtaining primary data from official sources were also screened for relevant information [18].

2.2. Eligibility of Studies, Measures of Food Insecurity and Food Insecurity Categorization Levels

All types of observational studies, as well as reviews, meta-analyses and reports from Greek and international official authorities, were included. Only articles published in English were examined. Articles that had no full text available were excluded. No restriction was applied regarding the year of publication. In addition, no restriction was applied on the methods, metrics and indicators used for measuring food insecurity in the individual studies (i.e., Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) survey module, which refers to household access to adequate food [19]; the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) [20]; the Household Dietary Diversity Scale (HDDS) [21]; the Household Hunger Scale (HHS) [22]; the Coping Strategies Index (CSI) [23]; the Global Hunger Index [24]; and a series of other proxy measures). Finally, we retained the categorization levels of food insecurity (i.e., non-severe, mild, moderate, severe) as described in the original studies. Specifically, several indexes/scales such as HFIAS and HHS have commonly-used cut-offs determining food insecurity levels, although different assumptions and methods underlie each measure’s cut-offs. On the other hand, universal categorization thresholds are not available for other indexes/scales (e.g., CSI). The different indicators used for measuring food insecurity per study are described in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Selected studies evaluating the magnitude of food insecurity (FI) globally.

Table 2.

Selected studies evaluating the magnitude of food insecurity (FI) in Europe.

3. Results

3.1. Magnitude of Food Insecurity

3.1.1. The World at a Glance

Available studies point towards an increasing trend in food insecurity. From 777 million people affected by hunger globally in 2015, the number of people affected rose above 820 million in 2019 [2,24]. Latest estimates show that in 2022 approximately 900 million people experienced severe food insecurity (i.e., struggled to meet their energy needs), corresponding to 11.3% of the world’s population [25]. The sheer magnitude of the problem skyrockets when considering hidden hunger, which is estimated to affect approximately two billion people across the world (mostly children and pregnant women in developing and low-income countries) [31].

Food insecurity comprises a hallmark of health inequalities both between and within countries and is largely interconnected to the social determinants of health [32]. It affects different socioeconomic groups in diverse forms and levels of gravity, dependent also on the territorial context/geographical macro-area of residence [2].

The majority of the world’s undernourished persons (more than 400 million in 2022) live in Asia, whereas more than 280 million live in Africa which displays the highest increasing rate of undernourishment [18,23,25]. The remaining are split amongst Europe, Australia and the Americas. As a share of the population, severe food insecurity is highest in Sub-Saharan Africa, where almost 33% of the population are defined as severely insecure [16,18], whilst as of 2019 the projected mid-ranges of the prevalence of undernourishment exceeds 25% in Eastern and Central Africa [25]. Moderate or mild food insecurity (i.e., affecting those who worry or struggle about accessing a healthy, nutritious diet), although highest in South Asia and African countries, poses an important public health issue across the globe, including developed and high–income countries [18,26]. Regarding food crises (i.e., situations in which food quantity and/or quality drastically decrease within a short period of time), Yemen, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Afghanistan, Venezuela and Ethiopia were the most severely affected countries in 2019 with a total of 60.1 million people affected by the crisis turmoil [1].

Overall, women appear to have a higher probability of being food insecure compared to men [27], whilst girls and adolescent females are more likely to report being food insecure than boys [2,33]. Particularly vulnerable are mothers with young children and pregnant women [3]. As regards children, the most vulnerable population group, in 2019 approximately 149 million children below the age of 5 years were stunted, nearly 50 million were wasted or subject to acute undernutrition, 340 million experienced systematic micronutrient deficiencies and 38.2 million were overweight or obese [28].

3.1.2. Europe and Greece

Europe is characterized by satisfactory levels of food security, compared to other continents. Specifically, in 2010, food insecurity prevalence in Europe was recorded at 2.7%; i.e., a considerably lower rate compared to other regions of the world, although higher than what was expected for the region based on previous trends [2,34]. Nonetheless, the risk and burden of food insecurity is not homogeneous amongst European Member States [29]. Recent data generated via the FAO’s FIES shows that the prevalence rates of food insecurity in European countries range from 3.1% to over 20% [30], peaking in Eastern and Southern European countries [34].

With the onset of the economic crisis in 2008, food insecurity escalated in Greece [29]. In 2015, more than 1.4 million people were estimated to have experienced food insecurity, corresponding to 12.9% of the country’s population [35]. Moderate/severe food insecurity prevalence appears slightly higher during the period 2014–2018, estimated at 14.5% [36]. In 2019, the Hellenic Statistical Authority reported that 8% of the Greek population experienced moderate or severe food insecurity, with1.5% of the population experiencing severe food insecurity [37]. Similar prevalence rates were recorded in 2022 when 6.6% of the population experienced moderate or severe food insecurity and 1.5% severe food insecurity [37].

According to the results of the Hellenic Statistical Authority’s Income and Living Conditions Survey (SILC) in 2020, 13.2% of the population worried about not having enough food to cover their needs, 12.8% were not able to sustain a healthy and nutritious diet, 14.1% of the population consumed only certain food groups, 6.2% were forced to skip a meal, 6.6% consumed less food than what they believed was necessary for their needs, 2.7% of the households experienced low food adequacy, 3.0% of the population was hungry but did not eat, and 2.2% did not consume foods during a whole day [38].

Regarding the burden of food insecurity in specific population groups, Gatton and Gallegos [36] found that, during 2014–2018, Greece reported the highest prevalence of moderate/severe food insecurity (12.2%) in those aged 65 years and above among 34 high income countries. Notably, a cross-sectional study conducted in Northern Greece in 2017 focusing on older adults revealed that 69% of the study population experienced some degree of food insecurity, while it found a positive association between food insecurity and a lower educational level, reduced monthly income and low adherence to the Mediterranean Diet [39]. Moreover, in a second study from Greece conducted in 2019, the prevalence of elder participants’ food insecurity reached 50.4%, with men and older adults malnourished or at risk for malnutrition displaying higher odds of food insecurity [40]. Additionally, another study conducted in Greece in 2019 indicated that, nearly a decade following the onset of the economic crisis, a notable and concerning percentage of adult participants in a food assistance initiative still suffered from protein and energy deficiencies [41].

University students in Greece, also appear to be affected by a certain level of food insecurity. The study conducted by Theodoridis et al. (2018) on a non-probability sample revealed a significant proportion of students (45.3%) experiencing severe food insecurity, while increased food insecurity was inversely correlated to students adhering to the Mediterranean Diet [42].

Existing evidence indicates that the economic crisis in Greece had a serious impact on food security for the most vulnerable population groups, especially children and adolescents. During the 2012–2013 and 2014–2015 school years, 56.3% and 45% of children’s households residing in the poorer socioeconomic areas of Greece experienced high levels of food insecurity [43,44].

Furthermore, a study examining diet quality and food insecurity in pairs of mothers and their children in Greece in 2017 reported that more than 1/4 (26.3%) of the pairs reported some degree of food insecurity, with a greater prevalence (64.7%) within single-mother families [45], while a pilot study on refugee children living in two reception centers in Greece revealed that 13.0% of the participants had at least one form of malnutrition, 7.8% were underweight and 7.3% were affected by stunting [46].

The main findings regarding the magnitude of food insecurity globally, in Europe and in Greece are summarized in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 3.

Selected studies evaluating the magnitude of food insecurity (FI) in Greece.

3.2. Macro-Factors Driving Food Insecurity

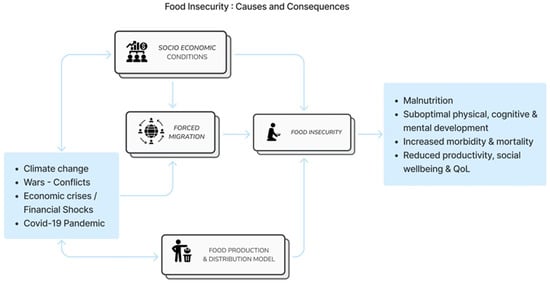

The root causes of food insecurity and their consequences on health are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Root Causes and Health Consequences of Food Insecurity.

3.2.1. Climate Change

Climate change and climate extremes (i.e., droughts, floods, heatwaves, and other phenomena) are currently undermining food availability, access, utilization and stability in many ways resulting in a downward spiral of increasing food insecurity and food crises [1].

Hunger is substantially worse in countries and regions with agricultural systems sensitive to droughts, rainfalls, and temperature changes and where the population’s livelihood is tied to agriculture production and agricultural product consumption [1]. Notably, between 2008 and 2018, climate induced extreme weather events and associated disasters in low- and middle-income countries caused an estimated crop and livestock production loss of 6.9 trillion kilocalories per year, which corresponds to the yearly energy intake of 7 million adults [47].

As global warming increases, the risks to food security become more serious and complex. Regarding agricultural production, the increase in temperature reduces the production yield of important crops (such as wheat, rice and maize), especially in areas where these crops are already at the limits of their temperature tolerance (mainly in tropical and temperate regions), while floods and droughts contribute to the removal of fertile topsoil [48]. In fact, a number of studies predict a reduction in crop production of up to 50% by 2050 in developing countries in South America, Africa and South/Southeast Asia as a result of a temperature rise by 3 °C [49]. It is estimated that extreme climate conditions could force an excess of 100 million more people into hunger and poverty by 2030 and displace 1 billion people by 2050 [49].

Food availability (referring to absolute food quantities, nutrient quality or dietary diversity) is further reduced by the need for increasing amounts of water for crops in areas affected by drought and increased temperature, a demand often unmet in countries with weak economies.

Climate change and extreme climatic events also largely impact the livestock and dairy industry [50]. Temperature increase (coupled with other climate phenomena, e.g., floods) impacts the quantity, availability and quality of food and water intended for animals, posing significant challenges in maintaining livestock numbers and managing grazing intensity (especially in pastoralist herder settings) [51].

Higher temperatures may also lead to the deterioration of animals’ health and development, affecting food intake levels, animal behavior and their metabolism [52]. Thermal stress is also often accompanied by reduced productivity and fertility and increased vulnerability to infectious diseases [53].

Climate variability and extremes and their underlying ties to food insecurity largely impact the lives of households with the lowest incomes [1]. Food utilization in developing countries and low-income households is undermined by temperature increases and rainfall pattern changes, which often drive and alter the population dynamics of insects, weeds and micro-organisms with detrimental effects on the quantity, quality and safety of stored food [54]. Extreme climate events also affect food distribution via the destruction of roads and other infrastructure, preventing markets from being stocked adequately and in a timely fashion [4].

Moreover, food access for low-income persons is affected by: (a) food price increases and volatility as a downstream effect of climate variability induced food loss at the production/distribution stage, as well as through (b) climate extreme induced diminished employment opportunities in the food (or other) sector, collectively resulting in income loss and inability to reach household food demands [55]. Furthermore, extreme climate events and subsequent environmental degradation reduce developing countries’ and low-income communities’ resilience and adaptive capacity, increasing their vulnerability to food insecurity, malnutrition and food crises [1,56].

3.2.2. Wars/Conflicts

Wars and armed conflicts are a major driver of intense food insecurity. It is indicative that all countries currently facing food crises and/or a high risk of famine are experiencing armed conflicts [57] whilst, according to the World Food Program (WFP), 60% of the world’s hungriest people live in conflict zones [58]. Currently, more than 35 million acutely food insecure people attributed to conflicts are situated in Asia and the Middle East, while conflict driven food insecurity is also reported at high levels in the Lake Chad Basin and Central Sahel (Africa) [4].

Wars and conflicts disrupt food systems and markets in multiple ways. They generate inflation, particularly in food prices (in addition, black markets often flourish in such circumstances) and reduce people’s capacity to produce, trade and buy, collectively resulting in food scarcity [59]. Conflicts also undermine food system infrastructure (e.g., food markets are almost non-existent in Yemen and several regions of Syria) and weaken economies, thus reducing employment and increasing poverty levels, further straining peoples’ access to adequate food [60]. Deterioration in public health systems in conflict zones also has a toll on crop and livestock production due to diseases and sickness [60].

A major side-effect of conflicts is the displacement of large populations, which are acutely susceptible to food insecurity along their treacherous journeys to seek safety and better lives, or upon their obligatory enclosure in refugee camps under poor living conditions where food is often scarce and inadequate in meeting their nutritional needs [4,46,61,62].

3.2.3. Economic Crises and Economic Shocks

In 2009 alone, the global financial and economic crisis forced an additional 100 million people into hunger, resulting in a total of 1 billion undernourished people across the globe [63]. In Europe, the 2008–2009 economic crisis increased food insecurity levels in nearly all countries [64]. Indicatively in 2013–2014, nearly 1 million people in the United Kingdom visited food banks (a proxy measure of food insecurity) [65,66]. Moreover, a study investigating the effect of the economic crisis on food insecurity in Greece found an increasing food insecurity trend over the period 2008–2015, coinciding with the implementation of austerity measures [67,68].

Nonetheless, the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 impacted food security in the developing world, with countries such as Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Haiti and Sudan affected most [4].

Financial and economic crises negatively affect food insecurity at the country and individual level through a number of channels. Economic crises, inherently tied to inflation and currency devaluation, significantly reduce incomes, while food prices stand high, reducing the purchasing power and access of low-income persons and households to adequate and high-quality food [4,69].

Specifically, households with low income spend less on food and tend toward low-cost meals that provide high amounts of sugar, saturated and trans fats, and sodium [70]. Moreover, many foods that are considered healthy (fruits, vegetables, fish) have a high cost, making them less affordable [71]. For instance, healthy dietary choices during austerity in Greece have been influenced negatively by diminishing consumer level financial affordability [72].

Economic crises also increase unemployment rates, hence reducing food purchasing power, while crisis-related factors, such as poor working conditions (e.g., non-conventional working hours, part-time work, etc.), increase food insecurity risk [73].

3.2.4. COVID-19 Pandemic Effect on Food Insecurity

It is difficult to definitively assess and evaluate the pandemic’s full impact on food insecurity levels. Even so, several public health agencies and organizations (e.g., WHO, FAO) estimated in 2021 an increase of at least 83 million undernourished people worldwide, possibly extending to 132 million, predominantly as a downstream result of the SARS-CoV-2 triggered economic crisis [47]. Moreover, in 2020 (the year of strict lockdowns in many countries), European food banks redistributed 68% more food compared to 2019 with a number of countries, including Greece, doubling their food distribution [74].

The COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted food security levels in both developed and developing countries [66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76]. For example, Nigeria reported significantly increased household food insecurity levels throughout 2020 compared to the pre-pandemic years [75], while 10% of American adults reported a threefold increase in food insecurity compared to pre-pandemic years [76]. Further evidence frοm the USA shows food insecurity prevalence exceeding 30% during the first 4 months of the pandemic in 2020 [77], whilst several USA surveys indicate a steep rise in food insecurity (post-pandemic onset) in households with children, in comparison to previous years [78,79].

The COVID-19 pandemic worsened food insecurity due to a number of reasons. Firstly, during the pandemic’s acute phase, agriculture and food systems were largely crippled (especially in developing countries), thus halting and even reverting economic growth [47]. Lockdown measures affected all stages of the food supply chain, including logistics [80]. Shortages, production falloffs and food export reductions were recorded in many countries, with the International Food Policy Research Institute estimating in 2021 a 25% reduction in agricultural food exports in developing countries [47].

Concomitantly to reduced food production, food prices increased, jointly resulting in reduced food availability and access [47]. Notably, a large number of small-scale farmers, vendors and food distributors utilizing unofficial marketplaces were impacted by the COVID-19 restriction measures, hindering supply delivery [81]. At the same time, food costs skyrocketed making food unaffordable for millions of people living in poverty [81].

Furthermore, the pandemic and associated economic recession led to an overall increase in poverty, unemployment, under-employment and working poverty with devastating downstream effects on food security especially in economically insecure households [3].

The main findings regarding key drivers of food insecurity are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Selected studies investigating the major macro-factors driving food insecurity (FI).

4. Discussion

Investigating the magnitude of food insecurity worldwide, we observed high levels of moderate and severe food insecurity across the globe, affecting hundreds of millions of people, impacting most socioeconomically deprived populations and areas. In Greece specifically, we found moderate or severe food insecurity prevalence rates ranging between 6.6% and 8% for the years 2019–2022 [37], necessitating food security action with a prime focus on the most vulnerable populations (i.e., children, refugees and socioeconomically deprived individuals). Furthermore, we identified several interrelated key drivers fueling food insecurity across the globe, including war, climate change and economic crises, with their negative impacts further amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our review findings align with food insecurity studies and reports available for 2024. According to the WFP, over 309 million people across 72 countries are facing acute levels of food insecurity in 2024 [83]. Specifically, latest evidence from the Gaza Strip describes one of the worst war-driven food crises ever recorded with over two million people currently facing highly acute food insecurity [84]. Moreover, reports from Yemen covering the period October 2023—February 2024 describe over 4.5 million people experiencing high level acute food insecurity, attributed to economic crisis, armed conflict, and climatic extremes [85,86]. Last but not least, food insecurity appears to be worsening in West and Central Africa where 49.5 million people are expected to experience hunger between June and August 2024, corresponding to a 4% increase compared to 2023 [87].

Overall, the world stands far from progressing towards the sustainable development goal 2 “Zero Hunger” and specifically the targets 2.1 “End hunger and ensure nutritious and sufficient food to all”, and 2.2 “Eradicate all forms of malnutrition”, by 2030 [17,88]. More so, amidst the unravelling global multi-crisis, we are standing at a critical crossroads: (a) further increase in food insecurity or (b) the application of new knowledge, tools, competences and good health, as well as inequality reduction policies tackling food insecurity, with an end goal of zero hunger across the globe.

Public health policies, such as intensifying humanitarian aid, including food aid programs [56,89] and setting up food banks, are definitely important relief measures to a number of people experiencing food insecurity [90,91]. However, in the best-case scenario, these measures may improve people’s food insecurity status only on a temporary basis; thus, they do not challenge the underlying causes and mechanisms of food insecurity.

Rather, eliminating food insecurity requires acting upon the interrelations of several sustainable development goals with food insecurity, including “Zero Poverty”, “Climate Action”, “Decent Work and Economic Growth”, “Reduced Inequalities” and “Responsible Consumption and Production” [15,92].

For instance, food insecurity is worsening concomitantly with food overproduction and massive food loss and waste [93,94,95,96], both governed by the existing system’s tendency to provide a constant oversupply of food to the western markets in support of the overconsumption model in place. Indicatively in the EU, approximately 131 kg of food waste per person were generated in 2021 [97].

Reducing food loss and waste, apart from being an ethical priority [98], may enhance food security through improving nutritional status and health in an environmentally sustainable manner [99], and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, a well-known driver of climate change [93,100]. Utilizing, in this direction, cutting edge technology across the food supply chain (including advancements in artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, robotics and automation [101]) may significantly reduce food loss [102].

FAO suggests integrating the right to adequate food in national food and nutrition security policies and programs. Key points of such policies include (a) identifying vulnerable groups, (b) addressing the underlying causes of food insecurity for each group, (c) establishing specific time-bound goals, and (d) integrating food insecurity policies in multisectoral policies [103,104]. Considering the burden of food insecurity in socioeconomically deprived populations, as well as their vulnerability to food insecurity amidst economic crisis contexts, implementing socioeconomic policies improving the financial and employment circumstances of low-income households may significantly decrease food insecurity prevalence and severity [105]. EU policies concerning food security and food crises appear to be receiving greater attention nowadays compared to the past. Between the Seventh Framework Programme (2007–2013) and Horizon 2020 (2014–2020), the number of EU-funded Research and Innovation projects related to food security has more than doubled, increasing from around 200 to over 450. Some projects have already demonstrated successful application, such as InnovAfrica, which introduced technologies and approaches to enhance food security in sub-Saharan Africa, resulting in positive impacts on agricultural systems. Additionally, the DiverIMPACTS project aimed to fully leverage the diversification of cropping systems, offering various benefits, such as improved food security, and a steady supply of agricultural products for feed [106].

Coupling such efforts with capacity building in developing countries and regional/global food distribution regulation policies aiming to ensure consistent food availability and accessibility in crisis (e.g., war-ridden) settings are essential if we are to curb food insecurity and prevent food crises [107].

Climate change is a key food insecurity driver, posing as essential both system sustainability and resilience against climatic extremes [108]. In a broader sense, the concept of Planetary Health, recently gaining increasing recognition, appears highly promising within the context of addressing climate change and its downstream effects on food insecurity.

Planetary Health focuses on two main interrelated axes: (a) the interactions between human activities and the natural environment and their imprint on the state of environmental and human health; and (b) the sustainability of human civilization, that is, the ability of global society to act in a way that is beneficial to its long-term survival through the challenging of existing political and socio-economic frameworks of human activity [109]. From a strategic standpoint, Planetary Health sets a theoretical framework against the status quo condition of health inequalities and food insecurity for the most vulnerable, through which the 2030 sustainable development goals “Climate Action” and the interrelated “Zero Hunger” may be realized.

Our study has several limitations. Although we thoroughly searched the international literature measuring the magnitude of food insecurity, we do not include here the entirety of available studies potentially meeting our inclusion/exclusion criteria. Hence, certain inter-regional or between-country food insecurity prevalence variations may not be described. A second limitation is that the included studies display a wide range of study designs, including usage of different indicators measuring the magnitude of food insecurity, making strict geographical and temporal comparisons difficult. Furthermore, in the absence of golden standard cut-offs determining the levels of food insecurity (e.g., moderate or severe), interpretation of food insecurity estimates described here by severity level requires caution [110]. Finally, we highlight several major macro-factors driving food insecurity, though other secondary contextual factors acting in conjunction with those identified and described may exist.

5. Conclusions

Food insecurity comprises a major global public health threat and currently the world stands far from progressing towards the 2030 sustainable development goal “Zero Hunger”. Key underlying food insecurity macro-drivers include climate change, economic crises and conflicts/wars, whilst the COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated food security inequalities to the disadvantage of socioeconomically deprived populations. Tackling food insecurity through addressing its key drivers is essential if we aim to progress towards succeeding in the goal of eliminating hunger worldwide.

Author Contributions

E.A.F. and T.V. performed the literature search; E.A.F. prepared the literature review and drafted the manuscript; E.A.F., T.V. and I.K. revised the manuscript; M.T., M.G.G., E.A., T.N.S., K.K., E.K. and T.V. critically reviewed, edited and revised the manuscript; T.V. supervised and coordinated the project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Athina Mikrou, designer, for her contribution to the manuscript with creation of the figures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. Transforming Food Systems for Food Security, Improved Nutrition and Affordable Healthy Diets for All; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaccia, E.; Naccarato, A. Food Insecurity in Europe: A Gender Perspective. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 161, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, Z.; Scott, S.; Visram, S.; Rankin, J.; Bambra, C.; Heslehurst, N. Food insecurity and the nutritional health and well-being of women and children in high-income countries: Protocol for a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Security Information Network. Global Report on Food Crises 2020. Joint Analysis for Better Decisions. 2020. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/publications/2020-global-report-food-crises (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Vassilakou, T. Childhood Malnutrition: Time for Action. Children 2021, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundersen, C.; Ziliak, J.P. Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, D.; Eivers, A.; Sondergeld, P.; Pattinson, C. Food Insecurity and Child Development: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Ford-Jones, E.L. Food insecurity and hunger: A review of the effects on children’s health and behaviour. Paediatr. Child. Health 2015, 20, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheets—Malnutrition. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- World Child Hunger Facts—World Hunger Education. World Hunger News. Available online: https://www.worldhunger.org/world-child-hunger-facts/ (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Weaver, L.J.; Fasel, C.B. A Systematic Review of the Literature on the Relationships between Chronic Diseases and Food Insecurity. Food Nutr. Sci. 2018, 9, 519–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, L.; Williams, J.V.A.; Lavorato, D.H.; Patten, S. Depression and suicide ideation in late adolescence and early adulthood are an outcome of child hunger. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 150, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Theodoridis, X.; Chourdakis, M.; Oikonomou, A.; Tirodimos, I.; Dardavessis, T. Food insecurity during childhood: Causes, prevalence, results and recommendations. Paediatriki 2017, 80, 186–199. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya, A.L.; Roberts, S. Stunting and future risk of obesity: Principal physiological mechanisms. Cad. Saude Publica 2003, 19 (Suppl. S1), S21–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, P.D.; Larson, N.M. The Hunger of Nations: An empirical study of inter-relationships among the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 12, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Hunger Index Organization. 2023 Global Hunger Index. Global, Regional and National Trends. Available online: https://www.globalhungerindex.org/trends.html (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Sustainable Development. The 17 Goals of Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P.; Roser, M. Hunger and Undernourishment. Our World in Data. 2023. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/hunger-and-undernourishment (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Voices of the Hungry. Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES). Available online: https://www.fao.org/in-action/voices-of-the-hungry/fies/en/ (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide (v3). Washington, DC, 2007: FHI 360/FANTA-2. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/eufao-fsi4dm/doc-training/hfias.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide (v.2). Washington, D.C.: FHI 360/FANTA, 2006. Available online: https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/HDDS_v2_Sep06_0.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Deitchler, M.; Ballard, T.; Swindale, A.; Coates, J. Validation of a Measure of Household Hunger for Cross-Cultural Use. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance II Project (FANTA-2), FHI 360, 2010. Available online: https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/HHS_Validation_Report_May2010_0.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Barrett, C.B. Measuring food insecurity. Science 2010, 327, 825–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of Food Insecurity in the World. Safeguarding against Economic Slowdowns and Downturns. Rome, 2019. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca5162en/ca5162en.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Urbanization, Agrifood Systems Transformation and Healthy Diets across the Rural–Urban Continuum. Rome, 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cc3017en/cc3017en.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Pereira, A.L.; Handa, S.; Holmqvist, G. Prevalence and Correlates of Food Insecurity among Children across the Globe, Innocenti Working Paper 2017-09; UNICEF Office of Research: Florence, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/IWP_2017_09.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Broussand, N.H. What explains gender differences in food insecurity? Food Policy 2019, 83, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2019. Children, Food and Nutrition: Growing Well in a Changing World. New York, 2019. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-of-worlds-children-2019 (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Tsapogias, C. Climate Crisis and Food Security in Europe. Master’s Thesis, Athens. 2023. Available online: https://polynoe.lib.uniwa.gr/xmlui/handle/11400/4173 (accessed on 16 January 2024). (In Greek).

- Loopstra, R. An overview of food insecurity in Europe and what works and what doesn’t work to tackle food insecurity. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30 (Suppl. S5), ckaa165.521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. The State of Food and Agriculture. Leveraging Automation in Agriculture for Transforming Agrifood Systems; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World: The argument. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1312–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadley, C.; Lindstromb, D.; Tessemac, F.; Belachewc, T. Gender bias in the food insecurity experience of Ethiopian adolescents. Social. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loopstra, R.; Reeves, A.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. Food insecurity and social protection in Europe: Quasi-natural experiment of Europe’s great recessions 2004–2012. Prev. Med. 2016, 89, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research. Food Bank: Instrument for Addressing Food Insecurity and Food Waste in Greece. Athens, 2017. Available online: http://iobe.gr/docs/research/RES_05_B_24102017_REP_GR.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024). (In Greek).

- Gatton, M.L.; Gallegos, D. A 5-year review of prevalence, temporal trends and characteristics of individuals experiencing moderate and severe food insecurity in 34 high income countries. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Press Release. Food Security. 2022 Survey on Income and Living Conditions. Piraeus. 2023. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/documents/20181/52ab7204-642e-cf81-f1ed-87f62f059174 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Press Release Food Security. 2020 Survey on Income and Living Conditions. Piraeus. 2021. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/el/statistics?p_p_id=documents_WAR_publicationsportlet_INSTANCE_qDQ8fBKKo4lN&p_p_lifecycle=2&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_cacheability=cacheLevelPage&p_p_col_id=column-2&p_p_col_count=4&p_p_col_pos=1&_documents_WAR_publicationsportlet_INSTANCE_qDQ8fBKKo4lN_javax.faces.resource=document&_documents_WAR_publicationsportlet_INSTANCE_qDQ8fBKKo4lN_ln=downloadResources&_documents_WAR_publicationsportlet_INSTANCE_qDQ8fBKKo4lN_documentID=478620&_documents_WAR_publicationsportlet_INSTANCE_qDQ8fBKKo4lN_locale=el (accessed on 20 December 2023). (In Greek).

- Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Gkiouras, K.; Theodoridis, X.; Tsisimiri, M.; Markaki, A.G.; Chourdakis, M.; Goulis, D.G. Food insecurity increases the risk of malnutrition among community-dwelling older adults. Maturitas 2019, 119, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkiouras, K.; Cheristanidis, S.; Papailia, T.D.; Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Karamitsios, N.; Goulis, D.G.; Papamitsou, T. Malnutrition and Food Insecurity Might Pose a Double Burden for Older Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzivagia, E.; Pepa, A.; Vlassopoulos, A.; Malisova, O.; Filippou, K.; Kapsokefalou, M. Nutrition Transition in the Post-Economic Crisis of Greece: Assessing the Nutritional Gap of Food-Insecure Individuals. A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, X.; Grammatikopoulou, Μ.; Gkiouras, K.; Papadopoulou, S.; Agorastou, T.; Gkika, I.; Maraki, M.; Dardavessis, T.; Chourdakis, M. Food Insecurity and Mediterranean diet adherence among Greek University students. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petralias, A.; Papadimitriou, E.; Riza, E.; Karagas, M.R.; Zagouras, A.B.A.; Linos, A.; on behalf of the DIATROFI Program Research Team. The impact of a school food aid program on household food insecurity. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalma, A.; Petralias, A.; Tsiampalis, Τ.; Nikolakopoulos, S.; Veloudaki, A.; Kastorini, C.M.; Papadimitriou, E.; Zota, D.; Linos, A.; on behalf of the DIATROFI Program Research Team. Effectiveness of a school food aid programme in improving household food insecurity; a cluster randomized trial. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggeli, C.; Patelida, M.; Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Matzaridou, E.-A.; Berdalli, M.; Theodoridis, X.; Gkiouras, K.; Persynaki, A.; Tsiroukidou, K.; Dardavessis, T.; et al. Moderators of food insecurity and diet quality in pairs of mothers and their children. Children 2022, 9, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Theodoridis, X.; Poulimeneas, D.; Maraki, M.I.; Gkiouras, K.; Tirodimos, I.; Dardavessis, T.; Chourdakis, M. Malnutrition surveillance among refugee children living in reception centres in Greece: A pilot study. Int. Health 2019, 11, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. The Impact of Disasters and Crises on Agriculture and Food Security. Rome, Italy, 2021. Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cb3673en (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Parry, M.; Rosenzweig, C.; Livermore, M. Climate change, global food supply and risk of hunger. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 2125–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Food Program USA. 14 Facts Linking Climate Change, Disasters & Hunger. Available online: https://www.wfpusa.org/articles/14-facts-climate-disasters-hunger/ (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Godde, C.M.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Mayberry, D.E.; Thornton, P.K.; Herrero, M. Impacts of climate change on the livestock food supply chain; a review of the evidence. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 28, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godde, C.M.; Boone, R.B.; Ash, A.J.; Waha, K.; Sloat, L.L.; Thornton, P.K.; Herrero, M. Global rangeland production systems and livelihoods at threat under climate change and variability. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 044021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipe, J.F.; Herrera, V.; Curone, G.; Vigo, D.; Riva, F. Floods, Hurricanes, and Other Catastrophes: A Challenge for the Immune System of Livestock and Other Animals. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevi, A.; Caroprese, M. Impact of heat stress on milk production, immunity and udder health in sheep: A critical review. Small Rumin. Res. 2012, 107, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Uzair, M.; Raza, A.; Habib, M.; Xu, Y.; Yousuf, M.; Yang, S.H.; Khan, M.R. Uncovering the Research Gaps to Alleviate the Negative Impacts of Climate Change on Food Security: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 927535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willenbockel, D. Extreme Weather Events and Crop Price Spikes in a Changing Climate: Illustrative global simulation scenarios. Research Report. OXFAM. 2012. Available online: https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/extreme-weather-events-and-crop-price-spikes-in-a-changing-climate-illustrative-241338/ (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Diamantis, D.V.; Katsas, K.; Kastorini, C.M.; Mugford, L.; Dalma, N.; Ramizi, M.; Papapanagiotou, O.; Veloudaki, A.; Linos, A.; Kouvari, M. Older People in Emergencies; Addressing Food Insecurity, Health Status and Quality of Life: Evaluating the “365+ Days of Care” Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brück, T.; d’Errico, M. Food security and violent conflict: Introduction to the special issue. World Dev. 2019, 117, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Food Program, U.S.A. What Causes Hunger. Available online: https://www.wfpusa.org/drivers-of-hunger/ (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Heinrich Böll Stiftung—The Green Political Foundation. War: Conflicts Feed Hunger, Hunger Feeds Conflict. 2021. Available online: https://www.boell.de/en/war-conflicts-feed-hunger (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Human Appeal. Hunger as a Weapon of War: How Food Insecurity Has Been Exacerbated in Syria and Yemen. United Kingdom, 2018. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/hunger-weapon-war-how-food-insecurity-has-been-exacerbated-syria-and (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Moffat, T.; Mohammed, C.; Newbold, K.B. Cultural Dimensions of Food Insecurity among Immigrants and Refugees. Hum. Organ. 2017, 76, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantopoulou, S.; Vassilakou, T.; Kontele, I.; Fouskas, T. Looking Arabs in the Teeth: Unveiling the Relation between Oral Health and Nutrition of Arabs in Greece; Chapter in Book Series Advances in Health and Disease; Duncan, L.T., Ed.; No. 58; Nova Sciences Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 49–89. ISBN 979-8-88697-192-7. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Food Security and the Financial Crisis. 2009. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/k6360e/k6360e.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Mittal, A. The 2008 Food Price Crisis: Rethinking Food Security Policies. G-24 Discussion Paper Series No. 56. United Nations. Geneva, 2009. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/gdsmdpg2420093_en.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- The Trussell Trust. Foodbank Use Tops One Million for First Time Says Trussell Trust. Press Release. UK, 2015. Available online: https://www.trusselltrust.org/2015/04/22/foodbank-use-tops-one-million-for-first-time-says-trussell-trust/ (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Ashton, J.R.; Middleton, J.; Lang, T. Open letter to Prime Minister David Cameron on food poverty in the UK. Lancet 2014, 383, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinidis, C. Food insecurity and the struggle for food sovereignty in the time of structural adjustment: The case of Greece. In Food Insecurity. A Matter of Justice, Sovereignty, and Survival; Mayer, T., Anderson, M.D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidis, C. Food insecurity, austerity, and household food production in Greece, 2009–2014. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2022, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, H.J.; de Pee, S.; Sanogo, I.; Subran, L.; Bloem, M.W. High Food Prices and the Global Financial Crisis Have Reduced Access to Nutritious Food and Worsened Nutritional Status and Health. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 153S–161S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A. Food insecurity has economic root causes. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 555–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. Challenges to the Mediterranean diet at a time of economic crisis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 26, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulierakis, G.; Dermati, A.; Vassilakou, T.; Pavi, E.; Zavras, D.; Kyriopoulos, J. Determinants of healthy diet choices during austerity in Greece. BFJ 2022, 124, 2893–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kim, Y.; Birkenmaier, J. Unemployment and household food hardship in the economic recession. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capodistrias, P.; Szulecka, J.; Corciolani, M.; Strøm-Andersen, N. European food banks and COVID-19: Resilience and innovation in times of crisis. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 82, 101187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, E. Food Insecurity Amid the COVID-19 Lockdowns in Nigeria: Do Impacts on Food Insecurity Persist After Lockdowns End? Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2021, 5, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Government. US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. Food Scarcity. June 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/hhp/#/?periodSelector=2&periodFilter=2 (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Drewnowski, A.; Otten, J.; Lewis, L.; Collier, S.; Sivaramakrishnan, B.; Rose, C.; Ismach, A.; Nguyen, E.; Buszkiewicz, J. Spotlight Series Brief: Washington State Households with Food Insecurity during the COVID-19 Pandemic, June to July 2020, Research Brief 7. Washington State Food Security Survey. January 2021. Available online: https://nutr.uw.edu/cphn/wafood/brief-7 (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Hake, M.; Dewey, A.; Engelhard, E.; Strayer, M.; Dawes, S.; Summerfelt, T. The Impact of the Coronavirus on Food Insecurity in 2020 & 2021. Feeding America 2021. Available online: https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/National%20Projections%20Brief_3.9.2021_0.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.A.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2021. Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=104655 (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Avery, A. Food Insecurity and Malnutrition. Kompass Nutr. Diet. 2021, 1, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Food Program USA. COVID-19 Pandemic Is Causing Global Hunger in Poor Countries. 2024. Available online: https://www.wfpusa.org/drivers-of-hunger/covid-19/ (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Gebeyehu, D.T.; East, L.; Wark, S.; Islam, M.S. A systematic review of the direct and indirect COVID-19’s impact on food security and its dimensions: Pre-and post-comparative analysis. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Food Programme. Global Operational Response Plan 2024—Update #10. WFP, February 2024. Available online: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000156760/download/?_ga=2.156345851.1907141673.1714023727-1895882399.1714023727 (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Integrated Food Security Phase Classification. Gaza Strip: IPC Acute Food Insecurity Analysis 15 February–15 July 2024—Special Brief. IPC, March 2024. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/occupied-palestinian-territory/gaza-strip-ipc-acute-food-insecurity-analysis-15-february-15-july-2024-special-brief (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Integrated Food Security Phase Classification. Yemen: Acute Food Insecurity Projection Update October 2023–February 2024. IPC, 2024. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-ipc-acute-food-insecurity-analysis-update-october-2023-february-2024-issued-february-2024-enar (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- World Food Programme. Emergencies: Sudan. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/emergencies/sudan-emergency (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- UNICEF. Food Insecurity and Malnutrition Reach New Highs in West and Central Africa as Funding to Address Acute Needs Dwindles. UNICEF, 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/wca/press-releases/food-insecurity-and-malnutrition-reach-new-highs-west-and-central-africa-funding (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- United Nations, United Nations Sustainable Development. Goal 2: Zero Hunger. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/hunger/ (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Kastorini, C.M.; Lykou, A.; Yannakoulia, M.; Petralias, A.; Riza, E.; Linos, A.; on behalf of the DIATROFI Program Research Team. The influence of a school-based intervention programme regarding adherence to a healthy diet in children and adolescents from disadvantaged areas in Greece: The DIATROFI study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Development Programme, Regional Bureau for Africa. Exploring the Role of Social Protection in Enhancing Food Security in Africa. NY, 2011. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/africa/Exploring-the-Role-of-Social-Protection-in-Enhancing-Food-Security-in-Africa.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Rizvi, A.; Wasfi, R.; Enns, A.; Kristjansson, E. The impact of novel and traditional food bank approaches on food insecurity: A longitudinal study in Ottawa, Canada. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Drumm, E. Implementing the SDG Stimulus. Sustainable Development Report 2023; SDSN: Paris, France; Dublin University Press: Dublin, Ireland, 2023; Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/sustainabledevelopment.report/2023/sustainable-development-report-2023.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Chalak, A.; Abou-Daher, C.; Chaaban, J.; Abiad, M.G. The global economic and regulatory determinants of household food waste generation: A cross-country analysis. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; De Hooge, I.; Amani, P.; Bech-Larsen, T.; Oostindjer, M. Consumer-Related Food Waste: Causes and Potential for Action. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6457–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations; Regional Information Centre for Western Europe. Food for Thought: Tackling Food Waste for a Sustainable Future. UNRIC, 2023. Available online: https://unric.org/en/food-for-thought-tackling-food-waste-for-a-sustainable-future/ (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention. Rome, 2011. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i2697e/i2697e.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Eurostat. Food Waste and Food Waste Prevention—Estimates. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Food_waste_and_food_waste_prevention_-_estimatesEurostat (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Tsekos, C.; Vassilakou, T. Food choices, morality and the role of environmental ethics. Philos. Study 2022, 12, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varzakas, T.; Smaoui, S. Global Food Security and Sustainability Issues: The Road to 2030 from Nutrition and Sustainable Healthy Diets to Food Systems Change. Foods 2024, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, A.; Browne, S. Food Waste and Nutrition Quality in the Context of Public Health: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aceto, G.; Persico, V.; Pescapé, A. Industry 4.0 and Health: Internet of Things, Big Data, and Cloud Computing for Healthcare 4.0. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2020, 18, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliem, H.P.; Mardianto, S.; Sumedi Suryani, E.; Widayanti, S.M. Policies and strategies for reducing food loss and waste in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 892, 012091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. The Right to Food. Policy and Programme. Available online: https://www.fao.org/right-to-food/areas-of-work/policy-programme/en/ (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- Food Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. The Right to Food Integrating the Right to Adequate Food in National Food Nutrition Security Policies Programmes Practical Approaches to Policy Programme Analysis, F.A.O. Rome, 2014. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/814a6044-b7f3-4e37-aefb-18851d9855f4/content (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- Dachner, N.; Tarasuk, V. Tackling household food insecurity: An essential goal of a national food policy. Can. Food Stud. 2018, 5, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Safeguarding Food Security and Reinforcing the Resilience of Food Systems. European Commission. Brussels, 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:5391557a-aaa2-11ec-83e1-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Committee on World Food Security. Global Strategic Framework for Food Security & Nutrition (GSF). CFS, 2013 (2nd Version). Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/cfs/Docs1213/gsf/GSF_Version_2_EN.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Kumar, L.; Chhogyel, N.; Gopalakrishnan, T.; Hasan, K.; Jayasinghe, S.L.; Kariyawasam, C.S.; Kogo, B.K.; Ratnayake, S. Climate Change and Future of Agri-Food Production; Chapter 4 in Future Foods Global Trends, Opportunities, and Sustainability Challenges; Bhat, R., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2021; pp. 49–79. ISBN 978-0323910019. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323910019000098 (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, D.; Vaitla, B.; Coates, J. How do indicators of household food insecurity measure up? An empirical comparison from Ethiopia. Food Policy 2014, 47, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).