Characterization of Semisweet and Sweet Wines from Kos Island Produced Traditionally and Conventionally

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

2.3. Chemical Analysis of Wines

2.4. Wine Color Determinations

2.5. Determination of Phenolics and Antioxidant Capacity

2.6. Elemental Analysis by ICP–OES of Wines

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Variation of Physicochemical Properties of Wines

3.2. Variation of Chromatic Parameters

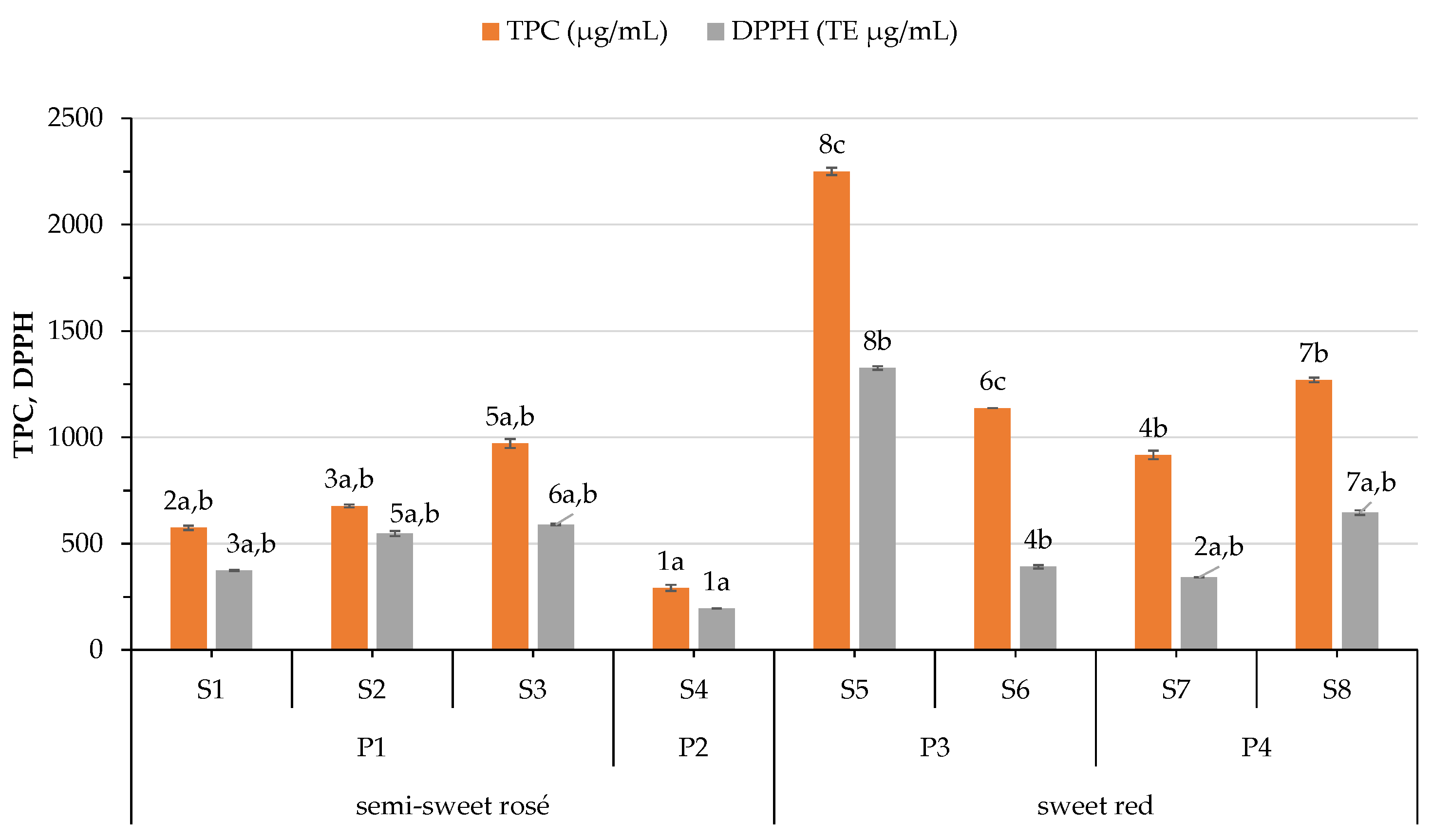

3.3. Variation on Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Capacity

3.4. Level of Elemental Concentrations in Wines

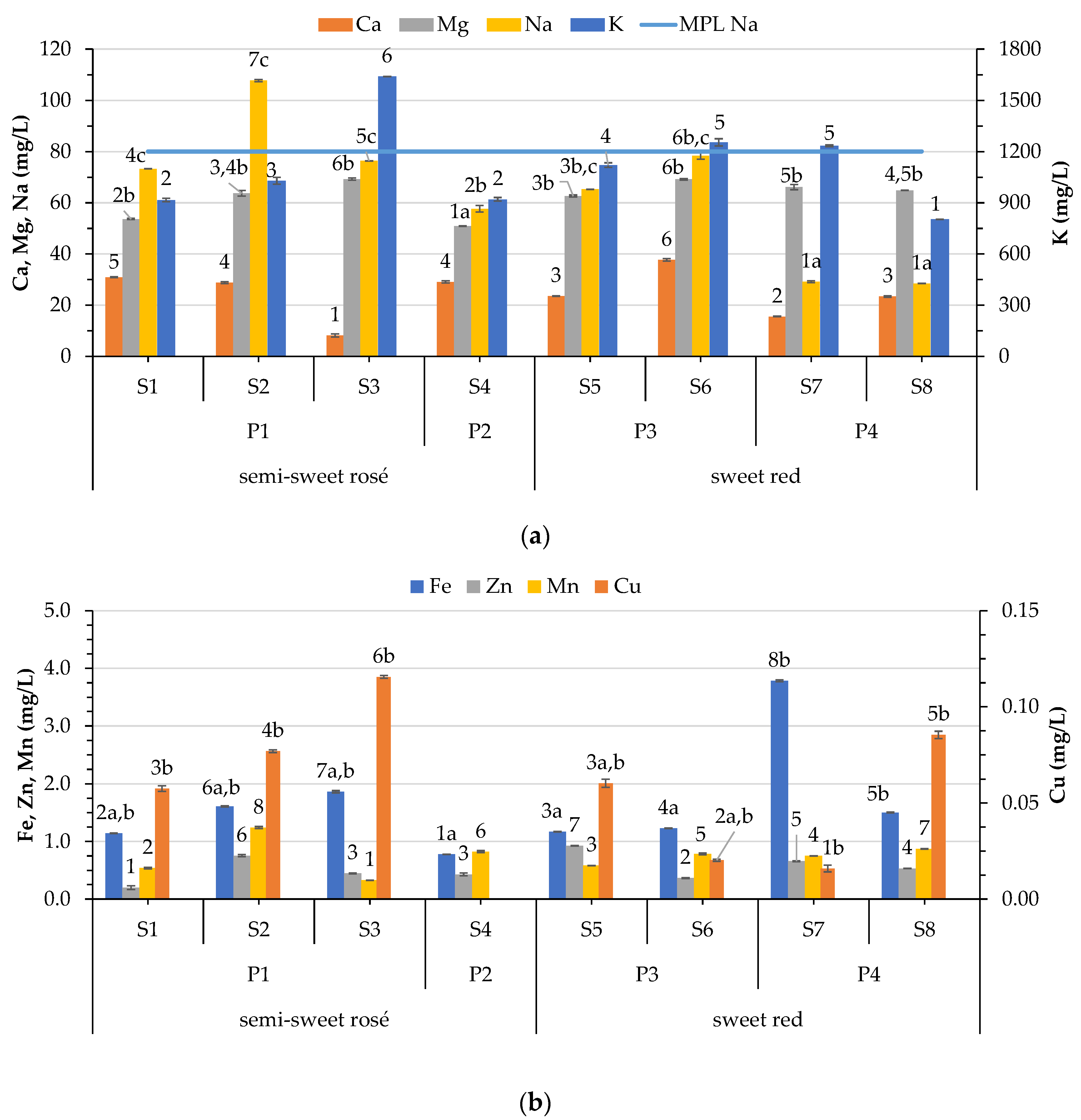

3.4.1. Variation of Macroelement Concentrations in Wines

3.4.2. Variation of Microelement Concentrations in Wines

3.4.3. Variation of Trace Element Concentrations in Wines

3.5. Chemometric Assessment of Wines

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EU. eAmbrosia the EU geographical indications register, File number PGI-GR-A0981, Registered 01/08/2009. In e-Ambrosia Database; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J.; Peinado, J.; Peinado, R.A. Antioxidant activity of musts from Pedro Ximénez grapes subjected to off-vine drying process. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.J.; Cerpa-Calderón, F.; Cohen, S.D.; Fang, Y.; Qian, M.; Kennedy, J.A. Effect of postharvest dehydration on the composition of pinot noir grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) and wine. Food Chem. 2008, 109, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peinado, J.; Lerma, N.; Moreno, J.; Peinado, R. Antioxidant activity of different phenolics fraction isolated in must from Pedro Ximénez grapes at different stages of the off-vine drying process. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellincontro, A.; De Santis, D.; Botondi, R.; Villa, I.; Mencarelli, F. Different postharvest dehydration rates affect quality characteristics and volatile compounds of Malvasia, Trebbiano and Sangiovese grapes for wine production. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2004, 84, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawel, R. Red wine astringency: A review. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 1998, 4, 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.A.; Matthews, M.A.; Waterhouse, A.L. Effect of maturity and vine water status on grape skin and wine flavonoids. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2002, 53, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.A.; Matthews, M.A.; Waterhouse, A.L. Changes in grape seed polyphenols during fruit ripening. Phytochemistry 2000, 55, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spayd, S.E.; Tarara, J.M.; Mee, D.L.; Ferguson, J.C. Separation of sunlight and temperature effects on the composition of Vitis vinifera cv. Merlot berries. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2002, 53, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forino, M.; Picariello, L.; Rinaldi, A.; Moio, L.; Gambuti, A. How must pH affects the level of red wine phenols. LWT 2020, 129, 109546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, R.F.; Cantos-Villar, E. Demonstrating the efficiency of sulphur dioxide replacements in wine: A parameter review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 42, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zara, G.; Nardi, T. Yeast metabolism and its exploitation in emerging winemaking trends: From sulfite tolerance to sulfite reduction. Fermentation 2021, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzálvez, A.; Armenta, S.; Pastor, A.; de la Guardia, M. Searching the most appropriate sample pretreatment for the elemental analysis of wines by Inductively Coupled Plasma-based techniques. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 4943–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallithraka, S.; Arvanitoyannis, I.S.; Kefalas, P.; El-Zajouli, A.; Soufleros, E.; Psarra, E. Instrumental and sensory analysis of Greek wines; implementation of principal component analysis (PCA) for classification according to geographical origin. Food Chem. 2001, 73, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.M.; Otero, M.; Alves, A.A.; Coimbra, J.; Coimbra, M.A.; Pereira, E.; Duarte, A.C. Elemental analysis for categorization of wines and authentication of their certified brand of origin. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, R.; Petric, I.V.; Jusup, J.; Banović, M. Geographical discrimination of Croatian wines by stable isotope ratios and multielemental composition analysis. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 625613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurđić, S.; Pantelić, M.; Trifković, J.; Vukojević, V.; Natić, M.; Tešić, Ž.; Mutić, J. Elemental composition as a tool for the assessment of type, seasonal variability, and geographical origin of wine and its contribution to daily elemental intake. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 2151–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabjanowicz, M.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. Metals and metal-binding ligands in wine: Analytical challenges in identification. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajek, M.; Pawlaczyk, A.; Szynkowska-Jozwik, M.I. Multi-elemental analysis of wine samples in relation to their type, origin, and grape variety. Molecules 2021, 26, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galani-Nikolakaki, S.M.; Kallithrakas-Kontos, N.G. Elemental content of wines. In Mineral Components in Foods; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo-González, M.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gándara, J. Effects on colour and phenolic composition of sugar concentration processes in dried-on- or dried-off-vine grapes and their aged or not natural sweet wines. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 31, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías, S.; Conde, J.E.; Rodríguez-Bencomo, J.J.; García-Montelongo, F.; Pérez-Trujillo, J.P. Classification of commercial wines from the Canary Islands (Spain) by chemometric techniques using metallic contents. Talanta 2003, 59, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías, S.; Trujillo, J.P.; Peña, E.; Conde, J.E. Classification and differentiation of bottled sweet wines of Canary Islands (Spain) by their metallic content. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2001, 213, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, R.; Malegori, C.; Oliveri, P.; Medici, I.; Cavaglioni, A.; Rossi, C. Prediction of quality parameters in straw wine by means of FT-IR spectroscopy combined with multivariate data processing. Food Chem. 2020, 305, 125512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feliciano, R.P.; Bravo, M.N.; Pires, M.M.; Serra, A.T.; Duarte, C.M.; Boas, L.V.; Bronze, M.R. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of Moscatel Dessert wines from the Setúbal region in Portugal. Food Anal. Method 2009, 2, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo-González, M.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gándara, J. Garnacha Tintorera-based sweet wines: Chromatic properties and global phenolic composition by means of UV–Vis spectrophotometry. Food Chem. 2013, 140, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo-González, M.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gándara, J.; Teixeira, N.; Mateus, N.; De Freitas, V. The phenolic chemistry and spectrochemistry of red sweet wine-making and oak-aging. Food Chem. 2014, 152, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo-González, M.; Regueiro, J.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gándara, J. Garnacha Tintorera-based sweet wines: Detailed phenolic composition by HPLC/DAD–ESI/MS analysis. Food Chem. 2014, 143, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, A.; Gambuti, A.; Piombino, P.; Moio, L. Sensory properties and aroma compounds of sweet Fiano wine. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguerol-Pato, R.; González-Álvarez, M.; González-Barreiro, C.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gándara, J. Evolution of the aromatic profile in Garnacha Tintorera grapes during raisining and comparison with that of the naturally sweet wine obtained. Food Chem. 2013, 139, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budić-Leto, I.; Humar, I.; Kljusurić, J.G.; Zdunić, G.; Zlatić, E. Free and bound volatile aroma compounds of ´Maraština´ grapes as influenced by dehydration techniques. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIV. International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV). In International Standard for the Labelling of Wines; OIV Publications: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OIV. International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV). In Compendium of International Methods of Wine and Must Analysis; OIV Publications: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Glories, Y. La couleur des vins rouges. lre partie : Les équilibres des anthocyanes et des tanins. OENO One 1984, 18, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendi, A.; Papageorgiou, M.; Stefanou, S. Preliminary Study of Microelements, Phenolics as well as Antioxidant Activity in Local, Homemade Wines from North-East Greece. Foods 2020, 9, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drava, G.; Minganti, V. Mineral composition of organic and conventional white wines from Italy. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IUPAC. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Nomenclature in evaluation of analytical methods including detection and quantification capabilities. Pure Appl. Chem. 1995, 67, 1699–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockley, C.; Paschke-Kratzin, A.; Teissedre, P.; Restani, P.; Tejedor, N.G.; Quini, C. SO2 and Wine: A Review, 1st ed.; OIV Publications/Francuska: Paris, France, 2021; OIV COLLECTIVE EXPERTISE DOCUMENT. [Google Scholar]

- EU. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/934 of 12 March 2019 supplementing Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards wine-growing areas where the alcoholic strength may be increased, authorised oenological practices and restrictions applicable to the production and conservation of grapevine products, the minimum percentage of alcohol for by-products and their disposal, and publication of OIV files. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, 149, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- EU. Commision Regulation (EC) No 606/2009 of 10 July 2009 laying down certain detailed rules for implementing Council Regulation (EC) No 479/2008 as regards the categories of grapevine products, oenological practices and the applicable restrictions. Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, 193, 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Costanigro, M.; Appleby, C.; Menke, S.D. The wine headache: Consumer perceptions of sulfites and willingness to pay for non-sulfited wines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrzębska, A. Determination of home-made wine selected parameters and study of honey addition impact on pro-healthy components content. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 248, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payan, C.; Gancel, A.-L.; Jourdes, M.; Christmann, M.; Teissedre, P.-L. Wine acidification methods: A review. OENO One 2023, 57, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C.A.; Morris, J.R. Effects of pH, sulfur dioxide, storage time, and temperature on the color and stability of red Muscadine grape wine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1984, 35, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paixão, N.; Perestrelo, R.; Marques, J.C.; Câmara, J.S. Relationship between antioxidant capacity and total phenolic content of red, rosé and white wines. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisov, N.; Čakar, U.; Milenković, D.; Čebela, M.; Vuković, G.; Despotović, S.; Petrović, A. The Influence of Cabernet Sauvignon Ripeness, Healthy State and Maceration Time on Wine and Fermented Pomace Phenolic Profile. Fermentation 2023, 9, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, P.J.; Francis, I.L.; Bartowsky, E.J. Variations in the effect of malolactic fermentation on the chemical and sensory properties of Cabernet Sauvignon wine: Interactive influences of Oenococcus oeni strain and wine matrix composition. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2012, 18, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaguso, I.; Nardini, M. Polyphenols content, phenolics profile and antioxidant activity of organic red wines produced without sulfur dioxide/sulfites addition in comparison to conventional red wines. Food Chem. 2015, 179, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, H.W.; Akiyoshi, M.; Amerine, M.A. Potassium and sodium content of California wines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1979, 30, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabani, M.P.; Arrúa, R.C.; Vázquez, F.; Diaz, M.P.; Baroni, M.V.; Wunderlin, D.A. Evaluation of elemental profile coupled to chemometrics to assess the geographical origin of Argentinean wines. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Frankowski, M.; Simeonov, V.; Polkowska, Ż.; Namieśnik, J. Determination of metals content in wine samples by Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry. Molecules 2018, 23, 2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, S.; Pinto, E.; Almeida, A.; Fernandes, E. Multi-elemental analysis as a tool for characterization and differentiation of Portuguese wines according to their Protected Geographical Indication. Food Control 2019, 103, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, F.D.; Călugăr, A.; Bunea, C.-I.; Rozsa, S.; Bunea, A. Assessment of physicochemical, macro- and microelements, heavy metals, and related human health risk from organically, conventionally, and homemade Romanian wines. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masayoshi, K.; Paola, V.; Linda, F.B. Imbalance of pH and potassium concentration as a cause of stuck fermentations. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1998, 49, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauff, D.B.; Santa-María, G.E. Potassium deprivation is sufficient to induce a cell death program in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010, 10, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schmidt, S.A.; Dillon, S.; Kolouchova, R.; Henschke, P.A.; Chambers, P.J. Impacts of variations in elemental nutrient concentration of Chardonnay musts on Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation kinetics and wine composition. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 91, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, R.R.; Blackmore, D.H. Potassium concentration and pH inter-relationships in grape juice and wine of Chardonnay and Shiraz from a range of rootstocks in different environments. Aust. J. Grape Wine R. 2012, 18, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kment, P.; Mihaljevič, M.; Ettler, V.; Šebek, O.; Strnad, L.; Rohlová, L. Differentiation of Czech wines using multielement composition—A comparison with vineyard soil. Food Chem. 2005, 91, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, R.M.; Ciani, M.; Walker, G.M. Magnesium, calcium and fermentative metabolism in wine yeasts. J. Wine Res. 2003, 14, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, C.; Conde, J.E.; Estévez, D.; Olivero, S.J.P.; Trujillo, J.P.P. Application of multivariate analysis and artificial neural networks for the differentiation of red wines from the Canary Islands according to the island of origin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 4303–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lima, M.T.R.; Cabanis, M.-T.; Cassanas, G.; Matos, L.; Pinheiro, J.; Cabanis, J.-C.; Blaise, A. Volcanic soils composition impact on the major mineral elements content of grapes and wines. OENO One 2003, 37, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, C.; Castells, J.E.; Adoración, E.; Berta, L.; Nuria, S. Iron, copper, and manganese influence on wine oxidation. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 1995, 46, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, G.; Larcher, R.; Pangrazzi, P.; Bontempo, L. Changes in the contents of micro-and trace-elements in wine due to winemaking treatments. Vitis 2004, 43, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza, I.; Salinas, I.; Caballero, I.; Santamaría, C.; Calvo, I.; García-Mina, J.M.; Fernández, J.M. Evolution of metal and polyphenol content over a 1-year period of vinification: Sample fractionation and correlation between metals and anthocyanins. Anal. Chim. Acta 2004, 524, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gambuti, A.; Picariello, L.; Rinaldi, A.; Moio, L. Evolution of Sangiovese Wines With Varied Tannin and Anthocyanin Ratios During Oxidative Aging. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, A.; Wang, H. Mechanisms of oxidative browning of wine. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariba, B. Metals in wine—Impact on wine quality and health outcomes. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 144, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkış, İ.M.; Öz, S.; Atakol, A.; Yılmaz, N.; Anlı, R.E.; Atakol, O. Investigation of heavy metal concentrations in some Turkish wines. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2014, 33, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dong, S.; Su, X. Copper and other heavy metals in grapes: A pilot study tracing influential factors and evaluating potential risks in China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granchi, L.; Ganucci, D.; Buscioni, G.; Mangani, S.; Guerrini, S. The biodiversity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in spontaneous wine fermentation: The occurrence and persistence of winery-strains. Fermentation 2019, 5, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Wine | Sample Code | Varietal Composition | Altitude | Treatment after Grape Harvest | Addition of SO2 | Production Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semisweet rosé | S1 | Muscat–Moschofilero | 35 | Grapes sun-dried for 1 week until ~18–19° Baume | Yes | Inoculation of must in tank. Fermentation is stopped by cooling to 9 °C for a few days. |

| S2 | Muscat–Merlot | 35 | Yes | |||

| S3 | Tempranillo | 25 | Harvesting when grapes reach ~17° Baume (vine-dried grape) | Yes | Inoculation of must with yeasts in tank. Fermentation is stopped by cooling to 0 °C. | |

| S4 | Assyrtiko–Syrah | 110 | Grapes sun-dried for 10 days until ~20–22° Baume | Yes | Spontaneous fermentation of the must. Fermentation stops due to the effect of osmotic pressure. | |

| Sweet red | S5 | Syrah | 45 | Harvesting when grapes reach ~14–14.5° Baume | Yes | Inoculation of pressed grapes. Added thyme honey (1 kg honey/10 L of wine). |

| S6 | Merlot–Syrah | 45 | Yes | |||

| S7 | Sultana–Syrah (40–60%) | 100 | Sultana traditional way without prior sampling The rest of grapes are harvested at 15.6–16.7° Baume | No | Part of Sultana must (S6)/Merlot must (S7) is boiled until 50% of the initial volume (“Κρύο -ψήμα” cold cooked must, CCM). Addition of CCM in the Syrah must until 18–18.5° Baume (S6)/the rest of grapes up to 18–22° Baume (S7). Spontaneous fermentation of the must. Fermentation stops due to the effect of osmotic pressure. | |

| S8 | Moschofilero (50%) Merlot (40%) Syrah (5%) Cabernet franc (5%) | 80 | No |

| pH | Total Acidity (Tartaric Acid g/L) | Free SO2 (mg/L) | Total SO2 (mg/L) | Alcohol Strength (vol. %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Wine | Process | Sample | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD |

| Semi-sweet rosé | P1 | S1 | 3.56 ± 0.05 3a | 5.55 ± 0.01 3a | 25.60 ± 0.42 6b | 130.45 ± 0.78 7c | 12.70 ± 0.14 2a |

| P1 | S2 | 3.70 ± 0.00 5a | 4.82 ± 0.05 1a | 10.25 ± 0.07 4b | 73.75 ± 0.92 4c | 12.00 ± 0.14 1a | |

| P1 | S3 | 3.91 ± 0.01 6a | 6.25 ± 0.08 5a | 16.10 ± 0.00 5b | 192.30 ± 0.71 8c | 14.00 ± 0.16 4a | |

| P2 | S4 | 3.35 ± 0.01 2a | 6.02 ± 0.05 4a | 64.60 ± 0.14 7c | 97.95 ± 0.78 6b,c | 12.00 ± 0.07 1a | |

| Sweet red | P3 | S5 | 3.57 ± 0.01 3a | 5.50 ± 0.04 3a | 6.80 ± 0.00 2a | 42.55 ± 0.35 3a,b | 13.00 ± 0.07 3a |

| P3 | S6 | 3.62 ± 0.01 4a | 7.49 ± 0.04 6a | 7.30 ± 0.42 2a | 76.20 ± 0.85 5a,b | 13.00 ± 0.06 3a | |

| P4 | S7 | 3.96 ± 0.01 6a | 5.33 ± 0.01 2a | 2.95 ± 0.21 1a | 15.60 ± 0.28 1a | 14.00 ± 0.06 4b | |

| P4 | S8 | 3.19 ± 0.02 1a | 8.38 ± 0.06 7a | 9.55 ± 0.21 3a | 29.55 ± 0.64 2a | 14.80 ± 0.03 5b |

| Cd (μg/L) | Pb (μg/L) | Ni (μg/L) | Cr (μg/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Wine | Process | Sample | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD |

| OIV Maximum Permissible Limit (μg/L) | 10 | 150 | - | - | ||

| Semisweet rosé | P1 | S1 | <LOD | <LOD | 102.92 ± 2.13 4b | <LOD |

| P1 | S2 | <LOD | <LOD | 88.59 ± 1.59 2b | 1.95 ± 0.17 2 | |

| P1 | S3 | 7.76 ± 0.01 2 | 53.22 ± 2.09 2 | 103.34 ± 2.88 4b | 0.78 ± 0.18 1 | |

| P2 | S4 | <LOD | <LOD | 79.90 ± 1.05 1a | <LOD | |

| Sweet red | P3 | S5 | <LOD | <LOD | 118.81 ± 1.54 5c | 1.83 ± 0.19 2 |

| P3 | S6 | 1.08 ± 0.29 1 | 32.02 ± 0.79 1 | 120.40 ± 3.02 5c | <LOD | |

| P4 | S7 | <LOD | <LOD | 97.81 ± 2.40 3b | <LOD | |

| P4 | S8 | <LOD | <LOD | 87.75 ± 2.02 2b | <LOD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skendi, A.; Stefanou, S.; Papageorgiou, M. Characterization of Semisweet and Sweet Wines from Kos Island Produced Traditionally and Conventionally. Foods 2023, 12, 3762. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12203762

Skendi A, Stefanou S, Papageorgiou M. Characterization of Semisweet and Sweet Wines from Kos Island Produced Traditionally and Conventionally. Foods. 2023; 12(20):3762. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12203762

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkendi, Adriana, Stefanos Stefanou, and Maria Papageorgiou. 2023. "Characterization of Semisweet and Sweet Wines from Kos Island Produced Traditionally and Conventionally" Foods 12, no. 20: 3762. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12203762

APA StyleSkendi, A., Stefanou, S., & Papageorgiou, M. (2023). Characterization of Semisweet and Sweet Wines from Kos Island Produced Traditionally and Conventionally. Foods, 12(20), 3762. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12203762