Gastronomic Experience and Consumer Behavior: Analyzing the Influence on Destination Image

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Model

2.1. Key Concepts

‘The total outcome involving a combination of customer’s cognitive, affective, emotional, social, and physical responses gained from participating in activities and interacting with both tangible and intangible components in the consumption process, which in turn influences how consumers interpret the world.’

2.2. Hypotheses Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures

3.2. Sample

3.3. Study Context

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sthapit, E. Exploring tourists’ memorable food experiences: A study of visitors to Santa’s official hometown. Anatolia 2017, 28, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.T.S.; Wang, Y.C. Experiential value in branding food tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, S.S. Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertella, G. Re-thinking sustainability and food in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Iwashita, C. Cooking identity and food tourism: The case of Japanese udon noodles. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2016, 41, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Power in Tourism Communities. Tourism in Destination Communities; Informatics Publishing: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, Q.-L.; Ab Karim, S.; Awang, K.W.; Abu Bakar, A.Z. An integrated structural model of gastronomy tourists’ behaviour. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 11, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causevic, S.; Lynch, P. Political (in)stability and its influence on tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, F. Memory of war in Croatia: Between tourism and nationalism. Balkan heritages: Negotiating history and culture. Plan. Perspect. 2017, 33, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, I.; Portela, S.L.; Dias, Á. Determinants of the perception of the personality of brand: An application to the Azores regional brand. Int. J. Acad. Res. 2013, 5, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.K.; Prayag, G. Gastronomic tourism experiences and experiential marketing. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2022, 47, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidis, G.; Markantonatou, S. Gastronomic tourism in Greece and beyond: A thorough review. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 21, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santich, B. The study of gastronomy and its relevance to hospitality education and training. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2004, 23, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.M. Culinary Tourism. J. Am. Folk. 2008, 121, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivela, J.; Crotts, J.C. Tourism and Gastronomy: Gastronomy’s Influence on How Tourists Experience a Destination. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S.; Suntikul, W.; Agyeiwaah, E. Determining the attributes of gastronomic tourism experience: Applying impact-range performance and asymmetry analyses. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 45, 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Okumus, F.; Okumus, B. Food Tourism as a Viable Market Segment: It’s All How You Cook the Numbers! J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckercher, B.; Chan, A. How Special Is Special Interest Tourism? J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.; Silva, G.M. Willingness to stay of tourism lifestyle entrepreneurs: A configurational perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Yeoman, I. What is food tourism? Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Ron, A.S. Understanding heritage cuisines and tourism: Identity, image, authenticity, and change. J. Herit. Tour. 2013, 8, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Evolving Gastronomic Experiences: From Food to Foodies to Foodscapes. J. Gastron. Tour. 2015, 1, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, R. Understanding the role of local food in sustaining Chinese destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 22, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panova, I.; Zhuravchak, Y. Problems and Prospects of Gastronomic Tourism Development in Ukraine (On the Example of Zakarpattia Oblast). J. V. N. Karazin Kharkiv Natl. Univ. Ser. Int. Relat. Econ. Ctry. Stud. Tour. 2021, 13, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillel, D.; Belhassen, Y.; Shani, A. What makes a gastronomic destination attractive? Evidence from the Israeli Negev. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Eves, A. Construction and validation of a scale to measure tourist motivation to consume local food. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1458–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, J.; Wood, C.; Payne, E.; Fouracre, H.; Lammyman, F. “Snack” versus “meal”: The impact of label and place on food intake. Appetite 2018, 120, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.M.; Richards, G. (Eds.) Tourism and Gastronomy; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson, B.J.; Beck, J.A. Identifying the Dimensions of the Experience Construct. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2004, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.E.; Kim, D.C.; Lehto, X.; Behnke, C.A. Destination restaurants, place attachment, and future destination patronization. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022, 28, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Youngman, P.A.; Hadzikadic, M. (Eds.) Complexity and the Human Experience: Modeling Complexity in the Humanities and Social Sciences; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Berbel-Pineda, J.M.; Palacios-Florencio, B.; Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M.; Santos-Roldán, L. Gastronomic experience as a factor of motivation in the tourist movements. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2019, 18, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendijani, R.B. Effect of food experience on tourist satisfaction: The case of Indonesia. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.; González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Patuleia, M. Creative tourism destination competitiveness: An integrative model and agenda for future research. Creat. Ind. J. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, N.A.; Commey, V.; Mohamed, B. Determinant factors of consumers choice of formal full service restaurants in Ghana. J. Hosp. Manag. Tour. 2022, 13, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, Á.L.; Gomes, M.F.M.; Pereira, L.; Costa, R.L. Local Knowledge Management and Innovation Spillover: Exploring Tourism Entrepreneurship Potential. Int. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. Eng. Technol. 2022, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.N.; Lumbers, M.; Eves, A.; Chang, R.C. Factors influencing tourist food consumption. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.C.Y.; Kivela, J.; Mak, A.H.N. Attributes that influence the evaluation of travel dining experience: When East meets West. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G.; Dubelaar, C. A General Theory of Tourism Consumption Systems: A Conceptual Framework and an Empirical Exploration. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.J.; Russo, J.E. Product Familiarity and Learning New Information. J. Consum. Res. 1984, 11, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, P.; Crotts, J.C. Antecedents of novelty seeking: International visitors’ propensity to experiment across Hong Kong’s culinary traditions. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 965–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Jang, S. Intention to Experience Local Cuisine in a Travel Destination: The Modified Theory of Reasoned Action. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. Culinary-gastronomic tourism—A search for local food experiences. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 44, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieson, A.; Wall, G. Tourism: Economic, Physical, and Social Impacts; Longman Scientific & Technical: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, J.; Jones, D.L. The Contribution of Local Cuisine to Destination Attractiveness: An Analysis Involving Chinese Tourists’ Heterogeneous Preferences. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 20, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Rojas, R.D.; Folgado-Fernandez, J.A.; Palos-Sanchez, P.R. Influence of the restaurant brand and gastronomy on tourist loyalty. A study in Córdoba (Spain). Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 23, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.C. The study of consumer behavior in event tourism-a case of the Taiwan Coffee Festival. J. Hum. Resour. Adult Learn. 2010, 6, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.K.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, S.K.; Babin, B.J. Festivalscapes and patrons’ emotions, satisfaction, and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.N.; Getz, D.; Dolnicar, S. Food tourism subsegments: A data-driven analysis. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; López-Guzmán, T. Protection of culinary knowledge generation in Michelin-Starred Restaurants. The Spanish case. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2018, 14, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, A.; Yüksel, F. Measurement of tourist satisfaction with restaurant services: A segment-based approach. J. Vacat. Mark. 2003, 9, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, D. Examining the Impact of Food Attributes and Restaurant Services on Tourist Satisfaction: Evidence from Mountainous State of India. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjos, C.J.F.; Marques, S.; Dias, A. The impact of Instagram influencer marketing in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. Eng. Technol. 2022, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarelli, A.; Brorström, S. Problematising place branding research: A meta-theoretical analysis of the literature. Mark. Rev. 2013, 13, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. An assessment of the image of Mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon the image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 18, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chi, C.G.Q.; Xu, H. Developing destination loyalty: The case of Hainan Island. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 547–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.O.; Sevón, G. Food-branding places—A sensory perspective. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2014, 10, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.A.; Williams, R.L., Jr.; Omar, M. Gastro-tourism as destination branding in emerging markets. Int. J. Leis. Tour. Mark. 2014, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martin, J.D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.S.; Tsai, C.T.S. Government websites for promoting East Asian culinary tourism: A cross-national analysis. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; López-Guzmán, T. Gastronomy as a tourism resource: Profile of the culinary tourist. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.C.; Román, C.; Guzmán, T.L.G.; Moral-Cuadra, S. A fuzzy segmentation study of gastronomical experience. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 22, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Explore Wine Tourism: Management, Development & Destinations; Cognizant Communication Corporation: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Viruel, M.J.; López-Guzmán, T.; Gálvez, J.C.P.; Jara-Alba, C. Emotional perception and tourist satisfaction in world heritage cities: The Renaissance monumental site of úbeda and baeza, Spain. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 27, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. Food and culture: In search of a Singapore cuisine. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, M.Y.; Cai, L.A. A Model of Virtual Destination Branding. In Tourism Branding: Communities in Action; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Okumus, B.; Okumus, F.; McKercher, B. Incorporating local and international cuisines in the marketing of tourism destinations: The cases of Hong Kong and Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björner, E.; Berg, P.O. Strategic creation of experiences at Shanghai World Expo: A practice of communification. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2012, 3, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gato, M.; Dias, Á.; Pereira, L.; da Costa, R.L.; Gonçalves, R. Marketing Communication and Creative Tourism: An Analysis of the Local Destination Management Organization. J. Open Innov. Technol. Market Complex. 2022, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Tepanon, Y.; Uysal, M. Measuring tourist satisfaction by attribute and motivation: The case of a nature-based resort. J. Vacat. Mark. 2008, 14, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Moital, M.; Da Costa, C.F.; Peres, R. The determinants of gastronomic tourists’ satisfaction: A second-order factor analysis. J. Foodserv. 2008, 19, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Zaman, M.H.; Hassan, H.; Wei, C.C. Tourist’s preferences in selection of local food: Perception and behavior embedded model. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Yun, N.; Kim, O.Y. Destination food image and intention to eat destination foods: A view from Korea. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 20, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kong, W.H.; Yang, F.X. Authentic food experiences bring us back to the past: An investigation of a local food night market. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Konge, L.; Artino, A.R. The Positivism Paradigm of Research. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrag, F. In Defense of Positivist Research Paradigms. Educ. Res. 1992, 21, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, D.; Solano-Sánchez, M.; López-Guzmán, T.; Moral-Cuadra, S. Gastronomic experiences as a key element in the development of a tourist destination. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 25, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Duarte, P. Destination image and loyalty development: The impact of tourists’ food experiences at gastronomic events. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.; Chi, C.G.-Q. Culinary Tourism as a Destination Attraction: An Empirical Examination of Destinations’ Food Image. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 531–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism Economics. Driving the Tourism Recovery in Ukraine. 2021. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/tourism-economics/craft/Google_Ukraine_Final.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- SATD. State Agency of Tourism Development. 2022. Available online: https://www.tourism.gov.ua/ (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3; SmartPLS: Bönningstedt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J. On the convergence of the partial least squares path modeling algorithm. Comput. Stat. 2009, 25, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usakli, A.; Kucukergin, K.G. Using partial least squares structural equation modeling in hospitality and tourism. International. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 3462–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. In. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Treating unobserved heterogeneity in PLS-SEM: A multi-method approach. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Baltar, F.; Brunet, I. Social research 2.0: Virtual snowball sampling method using Facebook. Internet Res. 2012, 22, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckathorn, D.D. Comment: Snowball versus Respondent-Driven Sampling. Sociol. Methodol. 2011, 41, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saufi, A.; O’Brien, D.; Wilkins, H. Inhibitors to host community participation in sustainable tourism development in developing countries. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. Local food: A source for destination attraction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braichenko, O.; Kravchenko, O. Ukraine, Food and History; Ïzhakultura: Kiev, Ukraine, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alekseeva, T. International tourism as a factor of European integration of Ukraine: Present and Future. Int. Econ. Relat. World Econ. 2019, 23, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basuk, D. Innovation Development of Gastotourism in Ukraine. Sci. Res. NYHT 2012, 45, 128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Gopinath, M.; Nyer, P.U. The role of emotions in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.L.; Cunha, I.; Pereira, L.; Costa, R.L.; Gonçalves, R. Revisiting Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises’ Innovation and Resilience during COVID-19: The Tourism Sector. J. Open Innov. Technol. Market. Complex. 2022, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silkes, C.A.; Cai, L.A.; Lehto, X.Y. Marketing To the Culinary Tourist. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatov, E.; Smith, S. Segmenting Canadian culinary tourists. Cur. Issues Tour. 2006, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Jerónimo, C.; Sempiterno, M.; Lopes da Costa, R.; Dias, Á.; António, N. Events and festivals contribution for local sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items |

|---|---|

| Knowledge Leong, Q.-L., Ab Karim, S., Awang, K.W. and Abu Bakar, A.Z. [7]. | Read about local food prior to travel. |

| Aware of local eating customs. | |

| Knowledgeable about local food. | |

| Informed about popular local food. | |

| Informed of the location of popular local food. | |

| Past experience Leong, Q.-L., Ab Karim, S., Awang, K.W. and Abu Bakar, A.Z. [7]. | Enjoyable. |

| Good quality service. | |

| Learnt about the local food culture. | |

| Enhanced travel experience. | |

| Destination brand José A. Folgado-Fernández, José M. Hernández-Mogollón, and Paulo Duarte [79] | Good infrastructures. |

| Well trained/good workmanship. | |

| Good living and working conditions. | |

| Communication of an appealing vision of the country. | |

| Attractive image. | |

| I will recommend this destination to family and friends. | |

| Food/Cuisine Shahrim Ab Karim and Christina Geng-Qing Chi [80] | Offers a variety of foods. |

| Offers good quality food. | |

| Offers regionally produced food products. | |

| Offers attractive food presentation. | |

| Offers exotic cooking methods. | |

| Offers delicious food. | |

| Dining/Restaurant Shahrim Ab Karim and Christina Geng-Qing Chi [80] | Offers reasonable price for dining out. |

| Offers many attractive restaurants. | |

| Offers easy access to restaurants. | |

| Offers varieties of specialty restaurants. | |

| Offers friendly service personnel. | |

| Offers restaurants menus in English. | |

| Food-related tourism activities Shahrim Ab Karim and Christina Geng-Qing Chi [80] | Offers food and wine regions. |

| Offers package tours related to food and wine. | |

| Offers a unique cultural experience. | |

| Offers an opportunity to visit street markets. | |

| Offers unique street food vendors. | |

| Offers various food activities, e.g., cooking classes and farm visits. | |

| Offers much literature on food and tourism. | |

| Gastronomic experience Moral-Cuadra, S., Acero de la Cruz, R., Rueda López, R. and Salinas Cuadrado, E. [78]. | Quality of the dishes. |

| Price. | |

| Installation. | |

| Atmosphere of the establishment. | |

| Innovation and new flavors of the dishes. | |

| Service and hospitality. | |

| Experience with traditional gastronomy. | |

| Offers genuine gastronomic products. | |

| Satisfaction Berbel-Pineda, J.M., Palacios-Florencio, B., Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M. and Santos-Roldán, L. [33]. | How important is gastronomy for you as a destination choice when travelling? |

| How important are gastronomic experiences for you when you choose a destination for your trip? | |

| How important is gastronomy for you in relation with the satisfaction of your trip? | |

| My level of satisfaction with the gastronomy has been significant. |

| Variable | Percentage | Variable | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 76.4% | Country of origin | Ukraine | 56.4% |

| Male | 23.6% | Other | 43.6% | ||

| Age | 18–29 | 76.4% | Gastronomic experience during the trip | Yes | 95% |

| 30–39 | 20% | No | 5% | ||

| 40–49 | 1% | ||||

| 50–59 | 1% | ||||

| Professional activity | Student | 36.4% | Education | High school | 17.5% |

| Full-time/part-time job | 45.5% | Associate degree | 21.3% | ||

| Self-employed/freelance | 16.4% | Bachelor’s degree | 43% | ||

| Master’s degree | 18.2% | ||||

| Unemployed | 1.8% |

| Latent Variables | α | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Cuisine | 0.874 | 0.904 | 0.615 | 0.784 | 0.437 | 0.257 | 0.491 | 0.493 | 0.533 | 0.635 | 0.433 |

| (2) Destination_brand | 0.845 | 0.890 | 0.619 | 0.384 | 0.787 | 0.538 | 0.752 | 0.689 | 0.658 | 0.645 | 0.688 |

| (3) Food_activities | 0.856 | 0.889 | 0.534 | 0.217 | 0.477 | 0.731 | 0.718 | 0.593 | 0.829 | 0.580 | 0.586 |

| (4) Gastro_experience | 0.908 | 0.926 | 0.613 | 0.469 | 0.673 | 0.643 | 0.783 | 0.776 | 0.701 | 0.743 | 0.744 |

| (5) Past_experience | 0.911 | 0.937 | 0.789 | 0.473 | 0.607 | 0.534 | 0.801 | 0.888 | 0.626 | 0.787 | 0.663 |

| (6) Prior_knowledge | 0.866 | 0.904 | 0.656 | 0.488 | 0.565 | 0.724 | 0.634 | 0.563 | 0.810 | 0.583 | 0.619 |

| (7) Restaurants | 0.802 | 0.858 | 0.504 | 0.566 | 0.537 | 0.489 | 0.646 | 0.684 | 0.493 | 0.710 | 0.802 |

| (8) Satisfaction | 0.908 | 0.942 | 0.845 | 0.420 | 0.605 | 0.549 | 0.692 | 0.611 | 0.557 | 0.683 | 0.919 |

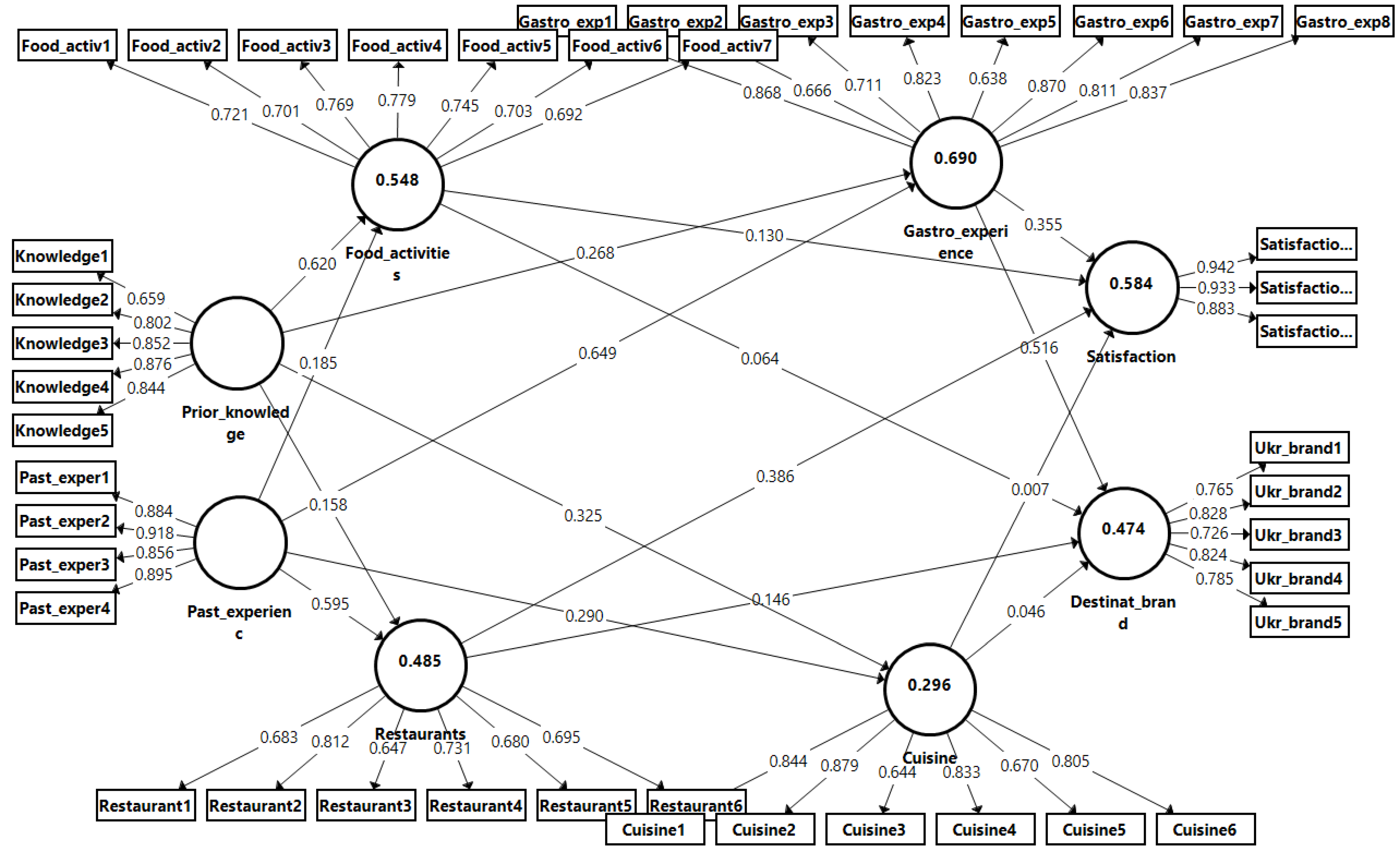

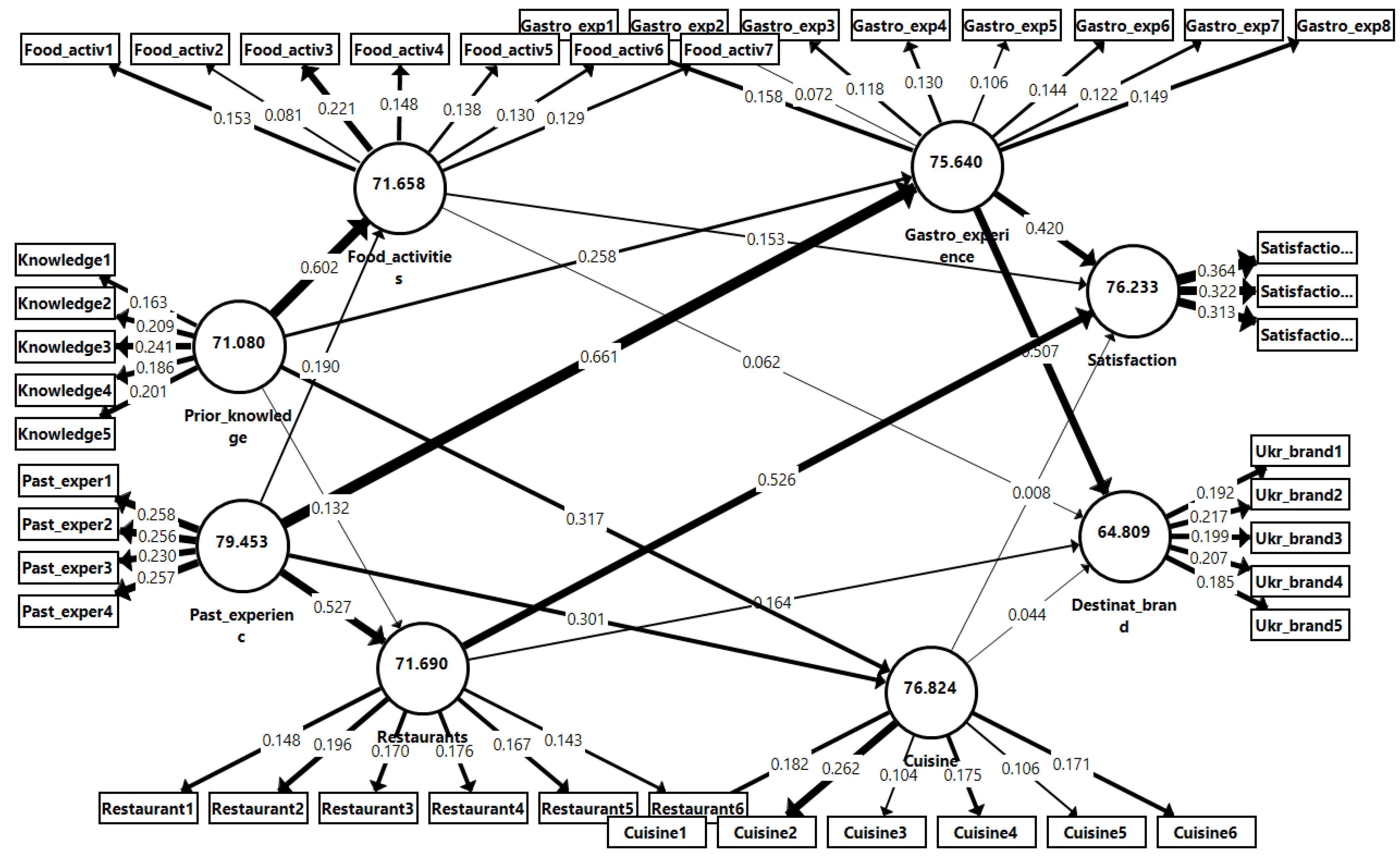

| Path | Path Coefficient | Standard Errors | t Statistics | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past_experience ® Cuisine | 0.290 | 0.133 | 2.185 | 0.029 |

| Past_experience ® Food_activities | 0.185 | 0.130 | 1.425 | 0.155 |

| Past_experience ® Gastro_experience | 0.649 | 0.102 | 6.370 | 0.000 |

| Past_experience ® Restaurants | 0.595 | 0.123 | 4.829 | 0.000 |

| Prior_knowledge ® Cuisine | 0.325 | 0.132 | 2.464 | 0.014 |

| Prior_knowledge ® Food_activities | 0.620 | 0.101 | 6.147 | 0.000 |

| Prior_knowledge ® Gastro_experience | 0.268 | 0.100 | 2.690 | 0.007 |

| Prior_knowledge ® Restaurants | 0.158 | 0.119 | 1.330 | 0.184 |

| Food_activities ® Destination_brand | 0.064 | 0.123 | 0.522 | 0.602 |

| Food_activities ® Satisfaction | 0.130 | 0.121 | 1.080 | 0.281 |

| Restaurants ® Destination_brand | 0.146 | 0.165 | 0.883 | 0.378 |

| Restaurants ® Satisfaction | 0.386 | 0.181 | 2.134 | 0.033 |

| Gastro_experience ® Destination_brand | 0.516 | 0.139 | 3.712 | 0.000 |

| Gastro_experience ® Satisfaction | 0.355 | 0.155 | 2.295 | 0.022 |

| Cuisine ® Destination_brand | 0.046 | 0.145 | 0.317 | 0.752 |

| Cuisine ® Satisfaction | 0.007 | 0.114 | 0.062 | 0.950 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kovalenko, A.; Dias, Á.; Pereira, L.; Simões, A. Gastronomic Experience and Consumer Behavior: Analyzing the Influence on Destination Image. Foods 2023, 12, 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12020315

Kovalenko A, Dias Á, Pereira L, Simões A. Gastronomic Experience and Consumer Behavior: Analyzing the Influence on Destination Image. Foods. 2023; 12(2):315. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12020315

Chicago/Turabian StyleKovalenko, Alina, Álvaro Dias, Leandro Pereira, and Ana Simões. 2023. "Gastronomic Experience and Consumer Behavior: Analyzing the Influence on Destination Image" Foods 12, no. 2: 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12020315

APA StyleKovalenko, A., Dias, Á., Pereira, L., & Simões, A. (2023). Gastronomic Experience and Consumer Behavior: Analyzing the Influence on Destination Image. Foods, 12(2), 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12020315