Abstract

This study examined consumers’ change in perception related to food delivery using big data before and after the COVID-19 crisis. This study identified words closely associated with the keyword “food delivery” based on big data from social media and investigated consumers’ perceptions of and needs for food delivery and related issues before and after COVID-19. Results were derived through analysis methods such as text mining analysis, Concor analysis, and sentiment analysis. The research findings can be summarized as follows: In 2019, frequently appearing dining-related words were “dining-out,” “delivery,” “famous restaurant,” “delivery food,” “foundation,” “dish,” “family order,” and “delicious.” In 2021, these words were “delivery,” “delivery food,” “famous restaurant,” “foundation,” “COVID-19,” “dish,” “order,” “application,” and “family.” The analysis results for the food delivery sentimental network based on 2019 data revealed discourses revolving around delicious, delivery food, lunch box, and Korean food. For the 2021 data, discourses revolved around delivery food, recommend, and delicious. The emotional analysis, which extracted positive and negative words from the “food delivery” search word data, demonstrated that the number of positive keywords decreased by 2.85%, while negative keywords increased at the same rate. In addition, compared to the pre-COVID-19 pandemic era, a weakening trend in positive emotions and an increasing trend in negative emotions were detected after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic; sub-emotions under the positive category (e.g., good feelings, joy, interest) decreased in 2021 compared to 2019, whereas sub-emotions under the negative category (e.g., sadness, fear, pain) increased.

1. Introduction

“Big data” refers to information that cannot be processed with the help of traditional tools. It is a huge volume of data generated worldwide in nearly all sectors of society [1]. Big data include a large number of structured or unstructured data sets that are difficult to handle with existing management methods or analysis systems. Data are also increasing due to the spread of smart devices, the activation of social networking services (SNSs), and the expansion of the Internet of Things (IoT) [2]. The online food delivery (OFD) industry is no exception, as consumers use online platforms to order food from a variety of restaurants and have it delivered at their convenience with just a few clicks [3]. In addition, consumers share their dining experiences, emotions, and thoughts through social media, blogs, and other online platforms [4]. In the food service industry, such big data are being actively used in various fields, including product development business management, marketing, and research [1,5].

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on consumer behaviors and perceptions related to dining out. Mayasari et al. [6] reported that people were submitting fewer Google queries about “restaurant” and searching more for “delivery” and “take-away.” In the real world, both new daily COVID-19 cases and stay-at-home orders had a negative impact on restaurant consumption, especially for full-service establishments [7]. In particular, a recent study [8] reported a sharp increase in daily food delivery orders along with growing COVID-19 cases and daily death reports. As such, due to the recent rapid change in the food service market, an in-depth study of consumer perceptions in the post-COVID-19 pandemic period is very important for market recovery [9].

This study presents an empirical study on post-pandemic behaviors as the number of meals at home has increased and the purchase of delivered food, rather than dining out, has also increased. As food delivery services now account for a large proportion of dining out experiences, research related to delivery services is becoming more active. However, more multifaceted research on consumers is needed, and in particular, research on how consumers’ perceptions have changed due to COVID-19 is still insufficient. COVID-19 has become a major turning point changing the demand and service for delivery services, making it important to study changes in consumers’ perception before and after the emergence of the pandemic. Therefore, this study aims to identify consumers’ perceptions of food delivery before and after COVID-19 through big data analysis using social networks. This paper is organized as follows. The section on related studies deals with recent study trends of dining out and food delivery in the era of COVID-19 and big data analysis in the food service industry, while the third section is dedicated to the presentation of the data and methodology. The section on results highlights the most remarkable findings, and the paper ends with an exploration of critical implications, limitations, and future studies.

2. Related Studies

2.1. Changes in Dining out Patterns after the COVID-19 Pandemic

As COVID-19 spread throughout the world in 2020, quarantine policies such as social distancing and controlling private gatherings were implemented in Korea to control the spread of the virus; in the case of the United States, strong quarantine measures and the suspension of dining out services were mandatory [10]. As a result, COVID-19 has brought about serious and profound changes in our lives, with countries being blocked and citizens staying at home and being restricted from going out [11]. This situation has also had a big impact on the global food service market and, accordingly, studies related to dining out about COVID-19 are being actively conducted. As a big change compared to previous studies of COVID-19, current studies are dealing with risk perception in the context of COVID-19 in the study of consumers’ dining out behaviors [12,13,14] and how COVID-19 has affected consumers’ eating out behaviors. Research on risk perception suggests that, when catastrophic events such as a global pandemic occur, people are initially likely to be influenced by risk perception along with optimistic bias [15]. The risk that consumers perceive from dining out during the COVID-19 pandemic may be due to potential contact with the virus when dining out [12]. Byrd et al. [12] assessed American consumers’ perceptions about the risks of contracting COVID-19 from various types of restaurant foods and restaurant service types as well as their packaging. Consumers were found to be most concerned about “food served in restaurants” as a risk of COVID-19, while “food in general” was the lowest concern. In addition, “food delivered by delivery service” and “food delivery by restaurants” were ranked in the middle but were perceived to be more dangerous than “food from carryout/curbside pick-up/drive-through” and “hot/cooked food from restaurants.” Yost and Cheng [13] suggested that, in the COVID-19 era, consumers’ dining out behaviors were based on an assessment of risk perception regarding health and safety and that trust, loyalty, and transparency, which are motivators of dining out, play an important role in managing these risk-based decisions. Therefore, this study argued that the factors of transparency, trust, and loyalty should be considered as major coordination factors when evaluating customers’ motivation to dine out in restaurants during the pandemic. Meanwhile, Dedeoglu and Bogan [14] investigated how consumers’ intention to visit luxury restaurants during the COVID-19 pandemic was influenced by dining out motivation and also whether COVID-19 risk perception and trust in government play a mediating role in their relationship. The results revealed that two motivations, sociability and affect regulation, had a positive effect on luxury restaurant visit intention and that consumers’ perceptions of COVID-19 risk and trust in the government mediated the relationship between these motivational factors and visit intention.

2.2. Food Delivery Service in the COVID-19 Pandemic

As the dining out business was hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic, it was essential to switch to non-contact services to make up for the loss [10]. In addition, non-contact dining has grown rapidly due to consumers’ high demands in the COVID-19 context [15]. Among them, food delivery service has accelerated development through delivery apps or online delivery due to the development of IT technology. In particular, due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the need for non-contact services has led to a large portion of food service sales [16]. According to the “2021 Domestic and International Dining Trend Report,” [16] which examined the differences in the proportion of sales by restaurant operation type before and after the pandemic in Korea, store sales decreased by 16.6% on average compared to before the pandemic, while both delivery and delivery orders increased by 31.2%. Considering the proportion by method, the use of delivery apps (58.9%) was the largest. Accordingly, since the COVID-19 outbreak, research into online food delivery among food-service-related companies has been actively conducted. According to Shroff, Shah, and Gajjar [17], 368 papers using keywords related to online food delivery were included in the Web of Science core collection between 2015 and 2021. Related review papers are also appearing one after another [17,18]. Kim, Kim, and Wang [8] examined pandemic-induced changes in the demand for restaurant delivery services and analyzed the dining out delivery sales to determine consumers’ cue utilization in their delivery choices. They found that dining out delivery sales increased significantly when the pandemic spread rapidly and remained flat even when the pandemic was suppressed. Dsouza and Sharma [19] re-examined consumer perceptions after the COVID-19 pandemic and compared whether previously judged parameters had the same effect or fundamental changes. They found that consumers considered safety to be a top priority when it comes to food; furthermore, awareness of this is increasing.

2.3. Big Data Analysis in the Food Service Industry

With the development of information and communication technology, along with the accumulation of data and the technology to analyze it, big data analyses have become essential for obtaining valuable insights into data [1]. Accordingly, research using big data is being actively conducted not only in industry but also in academia. Big data analysis is the process of finding hidden patterns and unknown information by effectively analyzing and processing this large number of data that cannot be processed with existing databases [20]. Through this, it is used to predict the future, find optimal countermeasures, and create new values [21]. Big data analysis methods can implement estimation modeling such as linear and artificial neural networks and support vector machines through structured data [22,23]. Through unstructured data, text mining, semantic network analysis, discourse analysis, sentiment analysis, and topic modeling can identify customer needs [21,24].

This study attempted to identify consumers’ perceptions of food delivery before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic by collecting and analyzing atypical data related to food delivery through social media. For this purpose, text mining, CONCOR analysis, and sentiment analysis were used. Text mining, a method of deriving meaningful keywords from unstructured data, is used for the purpose of deriving new information and knowledge [21,25]. In other words, it collects data related to natural language processing rather than structured data, establishes an analysis unit such as sentences or keywords in the text, and derives meaningful information based on the algorithm [21]. A CONCOR analysis is a method for explaining the meaning and characteristics of a cluster by classifying structural equivalence based on the correlation between keywords based on a semantic network analysis and then forming clusters with similar properties between keywords [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Finally, a sentiment analysis, also called opinion mining, is a natural language processing technique that allows researchers to automatically check the evaluations of and opinions about objects such as products and services [32]. In general, a sentiment analysis is used to classify emotions expressed in texts or convert them into objective numerical information; in a narrow sense, it can be seen as classifying positive and negative emotions in text [33]. It includes not only simply classifying positive and negative factors, but also analyzing the intention or position of the author by extracting positive and negative words [34]. Jeong and Choi [35] studied how COVID-19 affected the characteristics of using a mobile delivery order platform by using a text mining analysis to review the usage of the food service delivery order platform before and after the outbreak of COVID-19. To this end, Korean delivery application review data from 2019 to 2020 were collected and analyzed. Shin and Lee [5] conducted topic modeling and a semantic network analysis using Twitter’s big data with the keyword “Corona dining” and studied consumers’ perceptions of dining out during the pandemic era. Meanwhile, various studies related to COVID-19 have been attempted in the food-service-related field, but methods such as surveys, interviews, and secondary data analyses have mainly been applied, creating methodological limitations [5]. However, a big data analysis can be free of such limitations that make it difficult to generalize research results due to measurement errors of surveys and interviews, researchers’ subjective judgments, and limitations of samples [36,37,38]. A big data analysis is deemed useful for research in the field of food service as it is much more advantageous to obtain generalized information from a large number of data. Therefore, the current study used a big data analysis to examine consumers’ changing perceptions of the food delivery service before and after the onset of COVID-19, which can be widely used as basic data for research on dining out related to COVID-19 using big data.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data and Summary Statistics

The purpose of this study was to derive keywords related to “food delivery” from social media big data, as well as identify any keyword changes associated with delivery before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, to determine practical implications for the development of food service after the COVID-19 situation. To this end, relevant texts were collected from online cafes, news media, and blogs on online portal sites. Since it would have been difficult to collect data from undisclosed accounts on Facebook or Instagram, the data collection for this study was limited to blogs and cafes on Naver and Daum. These are the country’s major portal sites, which gather news data from numerous media outlets and show very active community and cafe activities; therefore, they contain the largest numbers of relevant data in Korea. So, it was considered very useful to identify consumers’ interests, current issues, and perceptions via cafes and blogs from the two portals. The data used in this study were collected from existing data using the keyword “food delivery” for a one-year period before the COVID-19 outbreak (from January 1 to 31 December 2019) and for a one-year period after the COVID-19 outbreak (from January 1 to 31 December 2021).

3.2. Methodology

For this study, data collected from online social media platforms were refined to examine any changes in consumer perceptions about food delivery before and after the COVID-19 outbreak. The study’s keyword for data retrieval was selected by domain experts in consideration of the purpose of the data analysis and the relevance of the retrieved keywords, and the data were collected by “The IMC,” a company specializing in big data. TEXTOM, a big data analysis solution, was employed for data extraction and analysis. The results of the frequency of important keywords extracted via TEXTOM were divided into similar groups, and then the analysis tool Ucinet6 was used to analyze meaningful relationships among the structures of connections among the keywords. Useful words were extracted, and major text-mining indexes, such as the frequency of occurrence and term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF; term frequency–inverse document frequency), were calculated through text mining. In addition, convergence of iteration correlation (CONCOR) analysis was performed to determine the associations among co-occurring words, and the analysis results were visualized. Finally, sentiment analysis was performed to identify the associations among the positive and negative emotions connected with keywords related to food delivery.

4. Results

4.1. Content Analysis

As a result of searching data with “food delivery” as a keyword, a total of 39,144 keywords were retrieved for 2019 (before the COVID-19 outbreak), and a total of 39,240 keywords were retrieved for 2021 (after the COVID-19 outbreak) (see Table 1). Given that 1000 words per channel are reported to be appropriate for TEXTOM-based data collection, the keywords collected for this study are considered sufficient. Narrative coding for food delivery involved clustering by food, sentiment, and demand/purpose (Table 2).

Table 1.

Survey of collected data.

Table 2.

Narrative coding index.

4.2. Text-Mining Analysis

According to the results of a frequency analysis (Table 3) on keywords in documents extracted using the keyword “food delivery,” “foodservice” was found to be the most commonly appearing keyword, followed by “delivery,” “famous restaurant,” “delivery food,” “foundation,” “dish,” “family,” “order,” and “delicious” in order of frequency. This result indicates how often these words appear from a search using the keyword “food delivery,” revealing their importance in such texts. Additionally, the TF-IDF values of keywords such as “foundation,” “side dish,” “pizza,” “tteokbokki,” and “sushi” were substantially higher than those of other keywords, which signifies that these keywords have a very good scarcity value within documents retrieved with the keyword “food delivery” and are significant keywords although they do not appear frequently. Since TF-IDF plays an important role in a short-term trend analysis by factoring in both the frequency of words and the interdocument irregularity of the appearance of words, it could be assumed that these keywords acted as major factors in food delivery trends in 2019. The results for the year 2021 are presented in Table 4. As in 2019, the word “dining-out” appeared most frequently, followed by “delivery,” “delivery food,” “famous restaurant,” “COVID-19,” “dish,” “order,” “application,” and “family” in order of frequency. In addition, the TF-IDF value was high for keywords such as “famous restaurant,” “discount,” “foundation,” “Delivery App.,” “pigs’ feet,” “side dish,” and “kitchen,” which means the frequency of these words in documents related to food delivery was good. This also shows that keywords such as “delivery food,” “discount,” and “lunch box,” which were not present prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, became very influential.

Table 3.

Text mining of food delivery (2019).

Table 4.

Text mining of food delivery (2021).

4.3. Sentimental Network Analysis

Based on the analysis results from text mining, food-delivery-related keywords were analyzed by dividing them into sentiment network and demand (purpose) network indexes. The position and role of each individual node were analyzed using semantic network indexes, and the associated attributes of highly relevant words were identified. There are four factors to consider in these indexes. First, a given variable’s higher value of degree centrality leads to a corresponding closer relationship between the variable and other variables, and thus these indexes can be interpreted as a factor that directly affects consumer sentiment and purpose. Second, a variable’s higher value of betweenness centrality means that this variable plays a greater mediating role when other variables appear. Therefore, this variable can be considered a factor that is highly dependent on consumer perceptions of sentiment and purpose. Third, a variable’s higher value of closeness centrality may indicate that when this variable interacts with other variables, a synergy effect can be created in terms of sentiment or purpose. Finally, a variable’s higher value for page rank means that this variable is more popular among consumers than other variables in terms of emotion or purpose. Therefore, this study performed a semantic network analysis of food delivery, combining the sentiments and demands (purposes) in the 2019 and 2021 data.

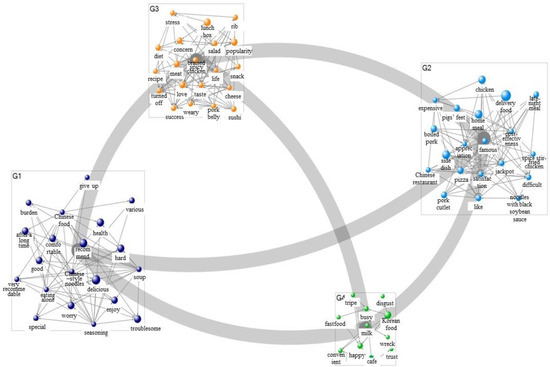

Table 5 presents the results of the semantic network analysis on food delivery and consumer sentiment in 2019. Regarding consumer sentiment about food delivery, the study confirmed the formation of discourses on keywords such as “delicious,” “recommend,” “delivery food,” “side dish,” “lunch box,” “popularity,” “love,” “Korean food,” and “happy” based on the degree of connection, betweenness centrality, and page link values. After each word’s group was created by clustering, a sentiment network was visualized (as shown in Figure 1). Based on the analysis results, food delivery was visualized into four categories: delicious, delivery food, lunch box, and Korean food. Accordingly, in 2019, people searched food delivery to get recommendations for places where they could order delicious and convenient delivery food.

Table 5.

Sentimental network index of food delivery (2019).

Figure 1.

Sentimental network visualization of food delivery (2019).

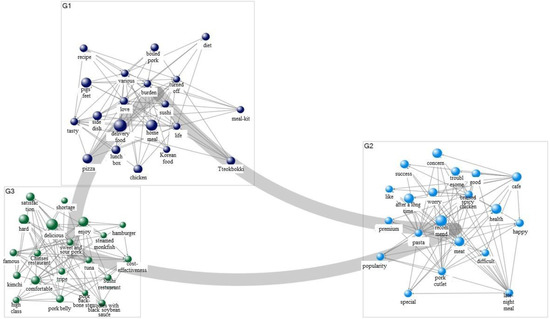

Table 6 presents the analysis results for a semantic network linking food delivery and sentiment in 2021, which shows the formation of discourses centered around keywords such as “delivery food,” “home meal,” “recommend,” “health,” “delicious,” and “hard.” The results of the visualization were divided into three categories: delivery food, recommend, and delicious (Figure 2). In 2021 (post-COVID-19), people engaged in more food delivery searches related to recommendations than in 2019 and showed an increased perception of struggling and being worried amid a hard situation. Notably, in 2019 (pre-COVID-19), sentiment-related keywords in food delivery formed the first-ranked group, whereas in 2021, keywords related to food itself were in the top ranks, indicating that the pattern of visualized figures itself has changed rapidly following the COVID-19 outbreak.

Table 6.

Sentimental network index of food delivery (2021).

Figure 2.

Sentimental network visualization of food delivery (2021).

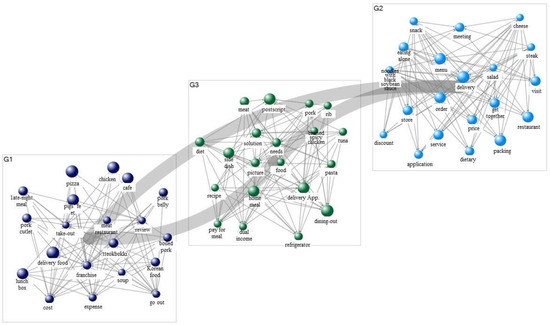

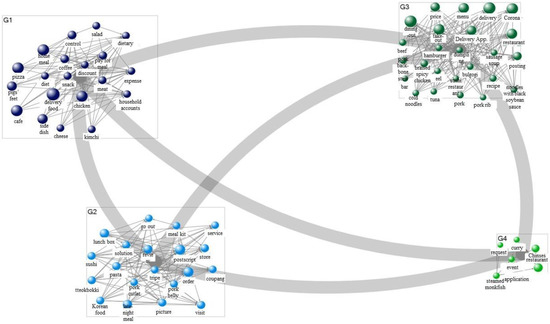

Table 7 presents the results of a semantic network connecting food delivery and demand (purpose) in 2019. Regarding the demand for food delivery, the study confirmed the formation of discourses with keywords such as “delivery food,” “pizza,” “chicken,” “menu,” “take-out,” “food service,” “reviews,” and “Delivery App.” In particular, it was necessary to pay attention to keywords such as “pizza” and “chicken” as delivery foods showed high values in the demand analysis results. This result implies that the most important purpose of searches related to food delivery before the COVID-19 outbreak was to order universal and representative delivery foods, such as pizza and chicken. As a result of the demand network visualization (Figure 3), food delivery in 2019 was divided into three categories: delivery food, delivery, and food service. In particular, consumers performed searches to fulfill the strong demand for deliverable foods. The analysis results for a semantic network combining consumer demands (purposes) for 2021 are shown in Table 8. Based on the demands for food delivery in 2021, the study confirmed the formation of discourses on keywords such as “delivery food,” “cafe,” “home meal,” “reviews,” “order,” “lunch box,” “delivery,” “foodservice,” “COVID-19,” and “application.” Notably, unlike in 2019, the most important purpose of keywords related to food delivery in 2021 (after the COVID-19 outbreak) was not the ordering of delivery foods that consumers had always ordered, such as chicken and pizza, but the ordering of everyday foods, such as home meals, meal kits, and lunch boxes. This was also observed in the demand network visualization (Figure 4), which was divided into four categories: delivery food, reviews, COVID-19, and application. This result suggests that during the COVID-19 situation, there was an increase in consumers ordering and purchasing their daily foods using apps. This indicates that the purpose of food delivery after the COVID-19 outbreak exhibits a very different pattern, revolving around ordering everyday food items, when compared to the purpose in 2019.

Table 7.

Demand network index of food delivery (2019).

Figure 3.

Demand network visualization of food delivery (2019).

Table 8.

Demand network index of food delivery (2021).

Figure 4.

Demand network visualization of food delivery (2021).

The analysis results discussed thus far can be summarized as follows: The sentiment network for food delivery in 2019 was formed around discourses with keywords such as “delicious,” “recommend,” “delivery food,” “side dish,” “lunch box,” “popularity,” and “love.” In 2021, discourses with terms such as delivery food, home meal, recommend, health, delicious, and hard emerged, and it is noteworthy that the feeling that things were “hard” appeared for the first time under the influence of COVID-19.

Moreover, the demand network for 2019 showed the co-appearance of keywords such as “delivery food,” “pizza,” “chicken,” “menu,” “take-out,” and “foodservice.” In 2021, keywords such as “delivery food,” “cafe,” “home meal,” “reviews,” “order,” and “lunch box” appeared together. This illustrates a strong contrast between the purposes of ordering food before and after COVID-19.

4.4. Sentiment Analysis

In this study, sentiment analysis—a natural language processing method for analyzing subjective data, such as people’s attitudes, opinions, and tendencies, from texts—was employed to extract and analyze positive and negative words from the data (Table 9). For this analysis, words were first classified using a dictionary for emotional vocabulary, which was produced independently by TEXTOM, and then the frequency of words and the intensity of their emotions were calculated. In a comparison of 2019 and 2021 in relation to food delivery, the number of positive keywords among the sentiment-based words decreased by 2.85%, whereas the number of negative keywords increased by 2.85% (Table 10 and Table 11). In particular, sub-emotions under the positive category (e.g., good feelings, joy, interest) decreased in 2021 compared to 2019, whereas sub-emotions under the negative category (e.g., sadness, fear, pain) increased.

Table 9.

Sentiment word frequency of food delivery.

Table 10.

Sentiment analysis of food delivery (2019).

Table 11.

Sentiment analysis of food delivery (2021).

5. Discussion and Implications

This study identified words closely related to the keyword “food delivery” based on big data from social media and investigated consumers’ perceptions of food delivery and related issues before and after COVID-19. The study findings can be summarized as follows. In 2019, a total of 17,728 food-delivery-related keywords appeared on social media, compared to 22,000 in 2021. In 2019, frequently appearing food-delivery-related words were “delivery,” “famous restaurant,” “delivery food,” “foundation,” “dish,” “family order,” and “delicious.” In 2021, they were “foundation,” “side dish,” “pizza,” “tteokbokki,” and “sushi.” Compared to 2019, famous restaurant, discount, foundation, and Delivery App produced high TF-IDF values in 2021, indicating consumers’ changing perceptions of food delivery after the COVID-19 outbreak. These findings are partially consistent with Jeong et al.’s study [39], which found that the number of food deliveries increased drastically after the coronavirus outbreak. Jung et al.’s study [40], which explored consumers’ perceptions of dining out before and after the onset of COVID-19 using big data analysis of social media, reported that delivery emerged as one of the new topics after COVID-19. In this study, the fact that “foundation” was a keyword both before and after the coronavirus proves the high demand in the delivery market (Table 3 and Table 4). In fact, according to a study by Chang, Park, and Kang [41], the number of food service establishments in Korea continued to increase during the COVID-19 period, including the acceleration of startups based on delivery platforms. Globally, online food delivery’s worldwide sales are expected to increase from USD 296 billion in 2021 to USD 466 billion by 2027 [42]. Accordingly, online food delivery apps are benefiting greatly. In Korea, the Delivery App.—the main keyword in 2021—has the largest market share [43]. However, given that a few apps dominate the market, service complaints such as high delivery app fees, delivery costs, and long waiting times are emerging as a hot topic in food delivery service [44]. Adak et al.’s study [45] also reported that common complaints in consumer reviews of food delivery services were related to waiting time, service and food quality, and cost. Jeong and Choi [35] analyzed the main topics of delivery order platform services before and after the outbreak of COVID-19 using text-mining techniques; the three topics classified as important after the emergence of the coronavirus included “dissatisfaction with the delivery platform in the corona situation” and “the feeling of betrayal about the monopoly of the delivery order platform.”

The sentiment analysis in this study demonstrated that positive keywords decreased by 2.85% while negative keywords increased at the same rate. Consumers’ dissatisfaction with the delivery service, as previously mentioned, is believed to have provoked negative emotions among consumers, and emotional keywords identified in this study, such as “after a long time” and “expensive,” can also be interpreted in the same context. Meanwhile, in the case of fear and pain among the negative emotion categories, the frequency percentage more than doubled after COVID-19, indicating that it was significantly strengthened compared to other emotions (Table 10 and Table 11). This finding is presumed to be related to the perception of risk related to dining out as well as negative emotions about such risk in the COVID-19 context. As the previously discussed related studies indicated, consumers’ dining out behaviors are based on risk perceptions for health and safety. In their study analyzing the importance and satisfaction of selection attributes for customers when choosing a restaurant to dine out, Ahn and Cho [46] reported that a “corona risk prevention strategy” was identified among restaurant attributes that customers considered important. In addition, Dsouza and Sharma [19] noted that, after the COVID-19 pandemic, consumers became more aware of safety in their dining experience as a top priority. In particular, the demand for delivery services surged due to the preference for non-contact consumption in the wake of COVID-19, although consumers still experienced some degree of risk perception of coronavirus contact even with delivered food or packages, as shown by Byrd et al.’s study [12]. From another point of view, one of the other problems associated with delivery services that can cause negative emotions is the excessive use of disposables in packaging. The amount of waste from hard-to-recycle straws, disposable tableware, and plastic bags is rapidly increasing with the increase in the consumption of delivered food [47]. Compared with the pre-COVID-19 era, the amount of plastic waste used has risen sharply, from 776 tons in 2019 to 923 tons in 2020—more than a 18.9% increase [48,49]. Eco-guilt refers to the guilt that individuals experience when they do not take an optional action to protect the environment when making a choice with value to the environment [50]. Kwak et al. [48] analyzed the effects of environmental awareness and guilt on eco-friendly behavior in the food delivery context and found that eco-guilt has a significant effect on eco-friendly behavior as well as when regulating the relationship between environmental awareness and eco-friendly behavior. The emotion-related keywords in the current study did not include the word “guilty.” However, considering the recent important issues regarding the delivery service [51] and the importance of Kwak et al.’s findings [48], it is assumed that some negative keywords in this study are related to eco-guilt.

Meanwhile, the keywords shown in the sentiment analysis of this study are related to important trends concerning food delivery. Recently, as a mega trend related to dining out in Korea, the importance of cost-effectiveness and single-person meals due to the increase in single-person households has been cited [16]. This trend is evident from the use of the keywords “eating alone” and “cost-effectiveness” in the results of the current study (Table 5). Furthermore, the demand for late-night meals has recently increased, as common keywords identified in this study demonstrate that, both before and after COVID-19, consumers used delivery services for late-night meals (Table 5 and Table 6). In fact, according to a recent newspaper article [52], the proportion of night delivery among all delivery orders also increased from about 7.2% in 2019 to 12.2% in 2020. This study also found keywords related to the demand network, such as “tripe,” “belly,” “pigs’ feet,” and “chicken,” which are generally preferred by Koreans as late-night snacks paired with alcohol (Table 7 and Table 8).

Meanwhile, in 2021, the keywords “meal-kit” and “premium” were newly emerged; they were not present in 2019. This finding highlights trends in the delivery market, which is pursuing differentiation through the recent high-end products as well as the diversification of products [51]. In fact, major food service delivery apps in Korea recently started selling meal kits, and delivery food service providers are trying to offer premium food and services to meet the needs of consumers oriented to premium food consumption [53,54]. Accordingly, existing fast-food-centered delivery food, including chicken and pizza, is gradually being changed into a variety of healthy and enjoyable menus that can be eaten like everyday food; this phenomenon is further discussed in the results section. These results show that big data analysis methods go beyond the limitations of surveys that have no choice but to identify the fragmentary attitudes and behaviors of consumers through structured questionnaires; they can also identify embedded consumer opinions and trends that cannot be measured with existing survey methods [5,36,37,38].

Food delivery services have increased sharply since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, but they are not expected to decrease significantly even after the end of the pandemic [41,55]. Accordingly, better products and improved service are essential for strengthening competitiveness. We believe that the results of this study have provided important insights to achieve this goal. Regarding the current study, we suggest policy proposals to develop the food and food service industry. First, compared to 2019, keywords such as “discount,” “foundation,” and “Delivery App.” became strongly influential and valuable in 2021, and these may be applied to post-COVID-19 dining out trend analyses. Moreover, developers and marketing personnel should pay attention to the trends highlighted by the keywords “eating alone,” “cost-effectiveness,” “late-night meals,” “meal-kit,” and “premium” in product development and promotion. After the pandemic emerged, customers showed great interest in home meals, delivery food, and lunch boxes, and, as a result, delivery food increased. In this result, the main discourses common to consumers’ emotions regarding food delivery before and after the onset of COVID-19 are “enjoy,” “new,” and “satisfaction.” At the same time, the increase in negative keywords such as “fear,” “pain,” and “anger,” once COVID-19 emerged suggests that there is a lot of anxiety among consumers about food delivery due to the pandemic. Accordingly, food service companies need measures for hygiene and food quality. In addition, industry officials will need to pay attention and take action on important delivery-related issues that can cause negative emotions for consumers, such as delivery service problems and environmental pollution caused by waste. Lastly, as consumers have both positive and negative emotions about food delivery, emotional marketing should be applied so that they can feel confident in their decision to have food delivered.

6. Limitation and Future Studies

This study has several limitations. First, due to the scarcity of academic research and big data analyses of food delivery, a comparative analysis with previous studies could not be sufficiently carried out. Second, as this study was collected from two portal sites (i.e., Naver and Daum), it cannot be said that it reflects all opinions. Future research should include Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter to further supplement this work. Finally, it is difficult to generalize the situation in Korea’s food service market because countries have different containment and quarantine measures due to COVID-19. Therefore, even if the subject and research method of this study are applied to other countries, it is believed that different meaningful results can be drawn only in that country. Finally, as this study cannot accurately identify the actual factors that increased negative emotions after COVID-19, the interpretations related to negative emotions mentioned herein are estimates based on important issues related to food delivery services for consumers. Therefore, factors related to consumers’ negative emotions toward delivery services should be clarified through follow-up studies.

This study empirically presented consumers’ perceptions of food delivery service before and after the COVID-19 pandemic using big data. The results are expected to provide fundamental marketing data for researchers and industry officials seeking to research and develop delivery food products and services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J. and J.J.; methodology, H.J. and E.L.; software, H.J. and E.L.; validation, H.J. and E.L.; formal analysis, H.J. and J.J.; investigation and data curation, H.J. and J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, H.J. and J.J.; writing—review and editing, J.J. and E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study can be made available by the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sadiku, M.N.O.; Ashaolu, T.J.; Ajayi, M.A.; Musa, S.M. Big Data in Food Industry. Int. J. Sci. Adv. 2020, 1, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. Network analysis on the recognition of ‘low cost carrier’ using social big data. Int. J. Tour. Manag. Sci. 2019, 34, 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, H. Understanding the experience and meaning of app-based food delivery from a mobility perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, S.; Wilk, V.; Lambert, C. A big data exploration of the informational and normative influences on the helpfulness of online restaurant review. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Lee, B. A study on the changes in dine-out consumer behavior to the Spread of COVID-19: An application of topic modeling and semantic network analysis. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 30, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayasari, N.R.; Ho, D.K.N.; Lundy, D.J.; Skalny, A.V.; Tinkov, A.A.; Teng, I.C.; Wu, M.C.; Faradina, A.; Mohammed, A.Z.M.; Park, J.M.; et al. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security and diet-related lifestyle behaviors: An analytical study of Google trends-based query volumes. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, H.B.; Chen, X. COVID-19 and restaurant demand: Early effects of the pandemic and stay-at-home orders. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 13, 3809–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Wang, Y. Uncertainty risks and strategic reaction of restaurant firms amid COVID-19: Evidence from China. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, P.; Sebby, A.G. The effect of online restaurant menus on consumers’ purchase intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracale, R.; Vaccaro, C.M. Changes in food choice following restrictive measures due to COVID-19. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. 2020, 30, 1423–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, K.; Her, E.S.H.; Fan, A.; Almanza, B.; Liu, Y.; Leitch, S. Restaurants and COVID-19: What are consumers’ risk perceptions about restaurant food and its packaging during the pandemic? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, E.; Cheng, Y. Customers’ risk perception and dine-out motivation during a pandemic: Insight for the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoglu, B.B.; Bogan, E. The motivations of visiting upscale restaurants during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of risk perception and trust in government. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivannan, P.; Kesavan, D.; Anuradha, M.R.; Vetrivel, V. Impact of COVID-19 on online food delivery industry with reference to operational and revenue parameters. Ugc Care J. 2020, 31, 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs; Korean Agro-Fisheries & Food Trade Corporation. Domestic and International dine-out trends. 2021. Available online: https://www.atfis.or.kr/fip/front/M000000216/board/list.do (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Shroff, A.; Shah, B.J.; Gajjar, H. Online food delivery research: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2852–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.; Han, S.P. Estimating demand for mobile applications in the new economy. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 1470–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, D.; Sharma, D. Online food delivery portals during COVID-19 times: An analysis of changing consumer behavior and expectations. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2021, 13, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Kang, M.M. Big data analysis technology today and the future. Commun. Korean Inst. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2014, 32, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.T. A study on the consumer perceptions of meal-kits using big data. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 35, 227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.T.; Lee, K.O. A study on the estimation of consumption expenditure of foodservice customers by machine learning algorithm. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 35, 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner. What is Data and Analytics? Gartner group. 2011. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/topics/data-and-analytics (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Kang, J.W.; Namkung, Y. Understanding consumers’ perceptions of the fresh-food delivery platform service based on big data: Using text mining and semantic network analysis. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 30, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotho, A.; Nürnberger, A.; Paaβ, G. A brief survey of text mining. LDV Forum 2005, 20, 19–62. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund, P.; Haemmerlé, O. Conceptual structures: Knowledge visualization and reasoning. Proceedings of 16th International Conference on Conceptual Structures, ICCS 2008, Toulouse, France, 7–11 July 2008; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gloor, P.; Diesner, J. Encyclopedia of Social Network Analysis and Mining, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 2350–2355. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.S. A content analysis of journal articles using the language network analysis methods. J. Korean Soc. Info. Manag. 2014, 31, 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Drieger, P. Semantic network analysis as a method for visual text analytics. Proced. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 79, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ji, Y. An exploratory study to derive a strategy to revitalize tourism metaverse: Focusing on text mining and semantic network analysis. Tour. Leis. Res. 2022, 34, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.S. A Study on the perception of Ulsan tourism and the promotion plans for the future through the analysis of social big data: Focused on CONCOR analysis methodology. N. Asian Tour. Res. 2020, 16, 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Kauter, M.; Breesch, D.; Hoste, V. Fine-grained analysis of explicit and implicit sentiment in financial news articles. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 4999–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.; Park, S.; Kim, W. Automatic construction of a negative/positive corpus and emotional classification using the internet emotional sign. J. KIISE 2015, 42, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.M.; Choi, K.W. A study on restaurant selection attribute & satisfaction using sentiment analysis: Focused on on-line reviews of foreign tourist. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 30, 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, M.Y.; Choi, K.W. Analysis of major topics for platform services for delivery orders before and after COVID 19 with the use of text mining techniques. Reg. Ind. Rev. 2021, 44, 283–305. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, R.M. Survey Errors and Survey Costs; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lyberg, L.; Weisberg, H. Total Survey Error, a Paradigm for Survey Methodology; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2016; pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.; Kim, H. A study on the sentiment analysis using big data of hotels online review. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 28, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.; Moon, Y.; Hwang, Y.H. Analysis for daily food delivery and consumption trends in the post-covid-19 era through big data. J. Korea Soc. Comp. Inform. 2021, 26, 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H.; Song, M.K. A study on dining-out trends using big data: Focusing on changes since COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.J.; Park, J.M.; Kang, J.Y. A study on the effect the infected number of COVID-19 on the number of food deliveries: Focusing on the mediating effect of the national disaster fund and social distancing. J. Int. Trade Commer. 2022, 18, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. eServices Report 2022–Online Food Delivery. Available online: https://www.statista.com/study/40457/food-delivery (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Sisa Journal. Delivery App ‘Second Territory War’ Started. Available online: http://www.sisajournal.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=237120 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Korean Rural Economic Institute. Food Consumption Behavior Research. 2021. Available online: https://www.krei.re.kr/krei/researchReportView.do?key=67&pageType=010101&biblioId=530219 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Adak, A.; Pradhan, B.; Shukla, N. Sentiment analysis of customer reviews of food delivery services using deep learning and explainable artificial intelligence: Systematic review. Foods 2022, 11, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.Y.; Cho, M.H. Exploring restaurant selection attributes using IPA during the COVID-19 pandemic-focusing on customer age and companion type. J. Hotel Resort 2020, 19, 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.M.; Lee, S.H.; Ahn, J.H. A brief review on global plastic regulation trends. J. Energy Eng. 2021, 30, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, Y.K.; Jeon, D.H. A study on the effect of environmental consciousness and eco-guilt on pro-environmental behavior of food delivery consumer—A moderating role of eco-guilt. J. Foodserv. Manag. Soc. Korea 2021, 24, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.K.; Kong, K.T. Post-Corona, post-plastics. BT NEWS 2021, 28, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett, R.K. Eco-guilt motivates eco-friendly behavior. Ecopsychology 2021, 4, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Chosun. Is the Delivery Garbage Okay? 2022. Available online: https://health.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2022/08/02/2022080201942.html (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- E-daily. Delivery Report-with the Increase in Home Alcohol, Popular Delivery Menu for Late-Night Meals and Snacks. 2022. Available online: https://www.edaily.co.kr/news/read?newsId=01397286628915752&mediaCodeNo=257&OutLnkChk=Y (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Seoul Economy. Attack of Coupang Mart vs. Expansion of Baemin One Delivery. 2021. Available online: https://www.sedaily.com/NewsView/22OT3QZC8H (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- MBC News. ‘Premium’ Lunch Box Sales Increase Due to COVID-19. 2021. Available online: https://imnews.imbc.com/replay/2021/nwtoday/article/6050414_34943.html (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Baker, S.R.; Farrokhnia, R.A.; Meyer, S.; Pagel, M.; Yannelis, C. How does household spending respond to an epidemic? Consumption during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 2020, 10, 834–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).