Factors Influencing Repurchase Intention in Drive-Through Fast Food: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

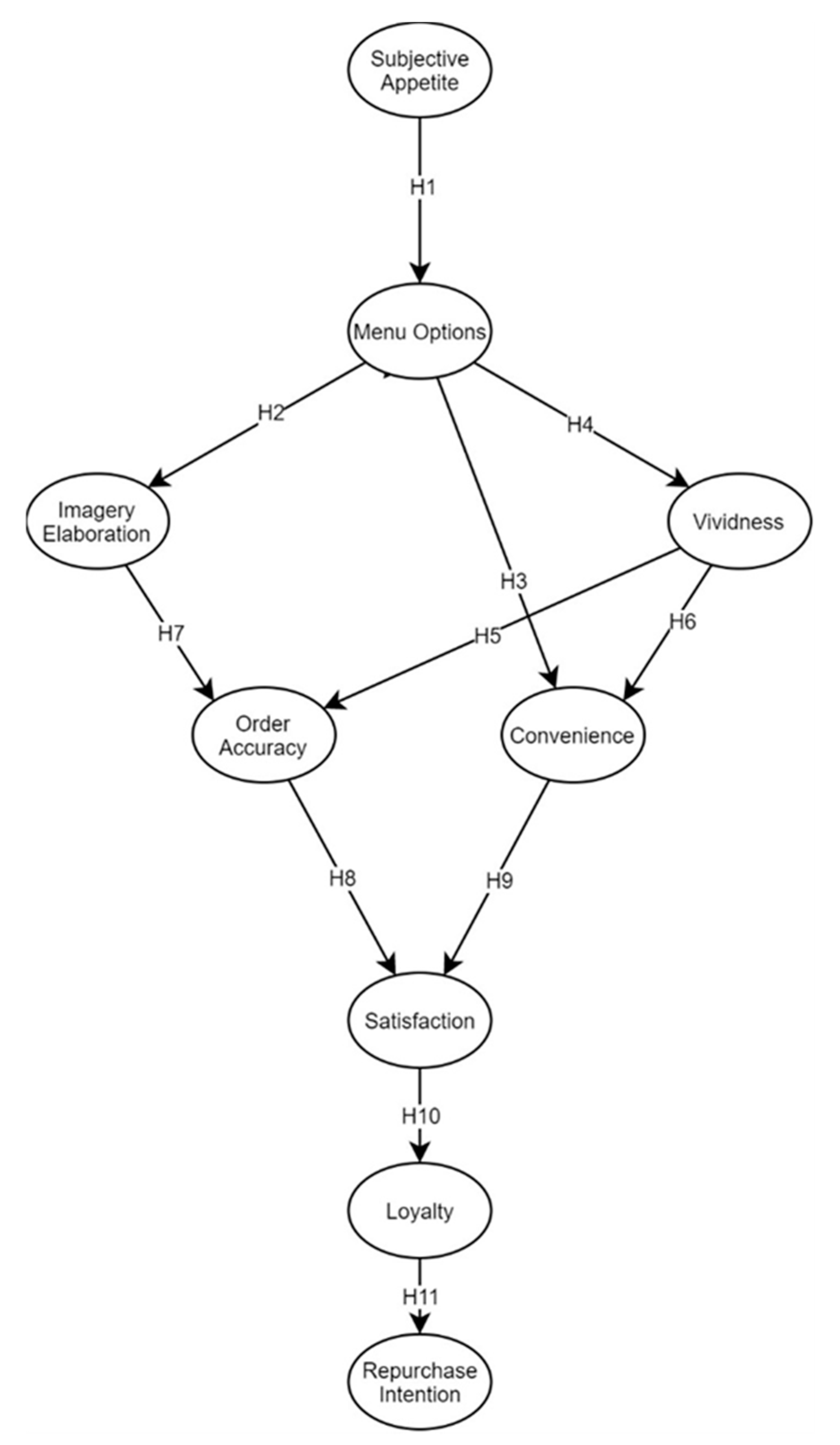

2. Theoretical Research Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Questionnaire

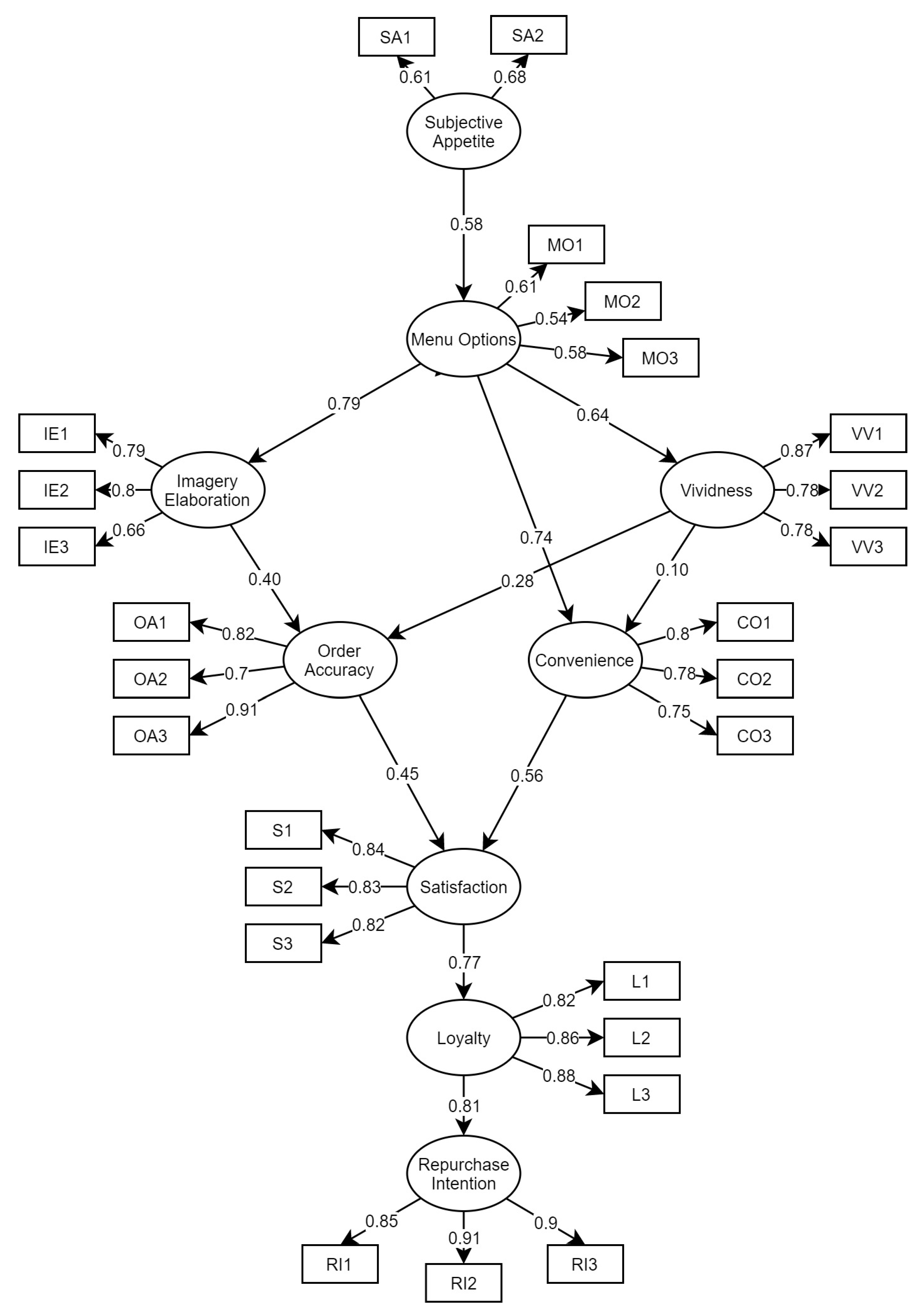

3.3. Structural Equation Modeling

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Direction

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, Y.-F.; Lin, Y.-M.; Sheng, L.-H.; Chien, H.-Y.; Chang, T.-J.; Zheng, C.-M.; Lu, H.-P. First drive-through pharmacy services in Taiwan. J. Chin. Med Assoc. 2013, 76, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnini, V.P.; Kim, S. The influences of restaurant menu font style, background color, and physical weight on consumers’ perceptions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkunas, M.; Rudienė, E. The Impact of Social Servicescape Factors on Customers’ Satisfaction and Repurchase Intentions in Mid-Range Restaurants in Baltic States. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Mills, J.E. Consumer knowledge and expectations of restaurant menus and their governing legislation: A qualitative assessment. J. Foodserv. 2006, 17, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-H.; Ham, S.; Yang, I.-S. A cross-cultural comparison of fast food restaurant selection criteria between Korean and Filipino college students. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matejowsky, T. Fast Food and Nutritional Perceptions in the Age of “Globesity”: Perspectives from the Provincial Philippines. Food Foodways 2009, 17, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J.T.; Morris, A.J. Menu design: Can menus sell. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1995, 7, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, C. Jollibee stings McDonald’s in Philippines. The New York Times. 31 May 2005. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/31/business/worldbusiness/jollibee-stings-mcdonalds-in-philippines.html (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Akram, U.; Ansari, A.R.; Fu, G.; Junaid, M. Feeling hungry? let’s order through mobile! examining the fast food mobile commerce in China. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namin, A. Revisiting customers’ perception of service quality in fast food restaurants. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Remaud, P.H. Factors influencing consumer menu-item selection in a restaurant context. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 82, 103887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Kim, M.G. Effective electronic menu presentation: From the cognitive style and mental imagery perspectives. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Taylor, S.A. SERVPERF versus SERVQUAL: Reconciling Performance-Based and Perceptions-Minus-Expectations Measurement of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Krivcova, M. Restaurant menu design and more responsible consumer food choice: An exploratory study of managerial perceptions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydell, S.A.; Harnack, L.J.; Oakes, J.M.; Story, M.; Jeffery, R.W.; French, S.A. Why Eat at Fast-Food Restaurants: Reported Reasons among Frequent Consumers. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 2066–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrens, W.; on behalf of the IDEFICS consortium. Sensory taste preferences and taste sensitivity and the association of unhealthy food patterns with overweight and obesity in primary school children in Europe—A synthesis of data from the IDEFICS study. Flavour 2015, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, J.; Rogers, P.; Hill, A. Uncoupling sweetness and calories: Methodological aspects of laboratory studies on appetite control. Appetite 1988, 11, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.J.; Magson, L.D.; Blundell, J.E. Hunger and palatability: Tracking ratings of subjective experience before, during and after the consumption of preferred and less preferred food. Appetite 1984, 5, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Mecklenbeck, M.; Sohn, M.; de Bellis, E.; Martin, N.; Hertwig, R. A lack of appetite for information and computation. Simple heuristics in food choice. Appetite 2013, 71, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Choi, S.; Mattila, A.S. Love is in the menu: Leveraging healthy restaurant brands with handwritten typeface. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 98, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.J.; De Houwer, J.; Lovibond, P.F. The propositional nature of human associative learning. Behav. Brain Sci. 2009, 32, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D.J.; Price, L.L. The Role of Imagery in Information Processing: Review and Extensions. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, D. How to’s of menu design and marketing. Restaur. Manag. 1988, 2, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio, A. Mental imagery in associative learning and memory. Psychol. Rev. 1969, 76, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilan, D.; Avello, M.; Abril, C. The mediating role of mental imagery in mobile advertising. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, L.A.; Burns, A.C. A modified scale for the measurement of communication-evoked mental imagery. Psychol. Mark. 1998, 15, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L.; Seiders, K.; Grewal, D. Understanding Service Convenience. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, J.R.; Thorson, E. The Effects of Progressive Levels of Interactivity and Vividness in Web Marketing Sites. J. Advert. 2001, 30, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodes, C.L. The Role of Visual Mental Imagery in the Speed-Accuracy Tradeoff: A Preliminary Investigation. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 1994, 23, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldona, S.; Buchanan, N.; Miller, B.L. Exploring the promise of e-tablet restaurant menus. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, D.J.; Andrade, J.; May, J. Imaginary Relish and Exquisite Torture: The Elaborated Intrusion Theory of Desire. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 112, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, S.; Kemps, E.; Tiggemann, M. The food craving experience: Thoughts, images and resistance as predictors of craving intensity and consumption. Appetite 2019, 133, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirumalai, S.; Sinha, K.K. Customer satisfaction with order fulfillment in retail supply chains: Implications of product type in electronic B2C transactions. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 23, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.E. Meeting the e-fulfillment challenge. Supply Chain Manag. Rev. 2000, 4, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yale, L.; Venkatesh, A. Toward the Construct of Convenience in Consumer Research. Adv. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, M.; Jimenez-Zarco, A.; Barba-Sánchez, V.; Yusta, A. Store Brand Proneness and Maximal Customer Satisfaction in Grocery Stores. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.; Chiu, S.; Hu, H.; Chang, Y. A study on exploring the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty in the fast food industry: With relationship inertia as a mediator. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 5118–5126. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Consumer Loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaid, S.; Behi, A.T. The role of attachment in building consumer-brand relationships: An empirical investigation in the utilitarian consumption context. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2011, 20, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; La, S. What influences the relationship between customer satisfaction and repurchase intention? Investigating the effects of adjusted expectations and customer loyalty. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, T.; Abratt, R.; Rhoades, D.L.; Dion, P. Customer Loyalty, Repurchase and Satisfaction: A Meta-Analytical Review. J. Consum. Satisf. Dissatisf. Complain. Behav. 2011, 24, 1–27. Available online: https://commons.erau.edu/db-management/18 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- McNeil, P.; Young, C.A. Customer satisfaction in gourmet food trucks: Exploring attributes and their relationship with customer satisfaction. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2019, 22, 326–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H.; Kim, T.-H. The relationships among overall quick-casual restaurant image, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza-Granizo, M.G.; Ruiz-Molina, M.-E.; Schlosser, C. Customer value in Quick-Service Restaurants: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-C.; Mohi, Z. Assessment of Service Quality in the Fast-Food Restaurant. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2015, 18, 358–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, R.B.; Khan, M.A.; Bufquin, D. Customer perceptions of “McService”’: Relationship with return intention. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 20, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A. Consumers’ willingness to buy and willingness to pay for fair trade food: The influence of consciousness for fair consumption, environmental concern, trust and innovativeness. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.-K.; Lee, Y.-S.; Hung, L.-M. The interrelationships among service quality, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty: Examination of the fast-food industry. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 20, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: Edinburg, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M. Structural Equation Modeling and Regression: Guidelines for Research Practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.M.; Fairhurst, A. Consumer shopping value, satisfaction, and loyalty for retail apparel brands. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2005, 9, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B.L.; Nguyen, N.; Phan, T.T.H.; Bui, L.P.; Moon, H.C. Investigating Consumer Attitude and Intention towards Online Food Purchasing in an Emerging Economy: An Extended TAM Approach. Foods 2019, 8, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Menendez, A.; Palos-Sanchez, P.R.; Saura, J.R.; Martin-Velicia, F. Understanding the Influence of Wireless Communications and Wi-Fi Access on Customer Loyalty: A Behavioral Model System. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018, 2018, 3487398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Rojas, R.D.; Folgado-Fernandez, J.A.; Palos-Sanchez, P.R. Influence of the restaurant brand and gastronomy on tourist loyalty. A study in Córdoba (Spain). Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 23, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Castillo, A.M.; Salonga, L.J.; Sia, J.A.; Seneta, J.A. Factors affecting perceived effectiveness of COVID-19 prevention measures among Filipinos during Enhanced Community Quarantine in Luzon, Philippines: Integrating Protection Motivation Theory and extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 99, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balinado, J.R.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Young, M.N.; Persada, S.F.; Miraja, B.A.; Perwira Redi, A.A. The Effect of Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction in an Automotive After-Sales Service. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Tanto, H.; Mariyanto, M.; Hanjaya, C.; Young, M.N.; Persada, S.F.; Miraja, B.A.; Redi, A.A. Factors Affecting Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in Online Food Delivery Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Its Relation with Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Senoro, D.B.; German, J.D.; Robielos, R.A.; Ney, F.P. Confirmatory factor analysis of vulnerability to natural hazards: A household Vulnerability Assessment in Marinduque Island, Philippines. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2009 PSIC Code | Industry Description | Number of Establishments | Employment as of November 15th | Total Income | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Paid Employees | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | ||

| Accommodation and Food Service Activities | 30,889 | 495,973 | 485,422 | 551,083,110 | |

| I55101 | Hotels and motels | 2767 | 69,828 | 69,026 | 90,171,024 |

| I55102 | Resort hotels | 1112 | 32,683 | 31,884 | 29,583,591 |

| I55103 | Condotels | 56 | 995 | 995 | 1,348,929 |

| I55104 | Pension houses | 399 | 3104 | 2881 | 1,202,641 |

| I55105 | Camping sites/facilities | 7 | 198 | 198 | 146,421 |

| I55109 | Other short term accommodation activities, n.e.c. | 124 | 985 | 856 | 706,546 |

| I55901 | Dormitories/boarding houses | 499 | 3030 | 3030 | 1,871,232 |

| I55909 | Other accommodation, n.e.c. | 29 | 144 | 142 | 72,063 |

| I56101 | Restaurants | 7218 | 130,965 | 129,521 | 129,761,811 |

| I56102 | Fast-food chains | 4411 | 138,051 | 137,002 | 203,007,168 |

| I56103 | Cafeterias | 4725 | 33,854 | 30,204 | 27,859,684 |

| I56104 | Refreshment stands, kiosks, and counters | 4209 | 33,332 | 32,986 | 25,857,313 |

| I56109 | Other restaurants and mobile food service activities, n.e.c. | 1679 | 5566 | 5275 | 9,513,724 |

| I56210 | Event catering | 442 | 7517 | 7324 | 7,395,711 |

| I56290 | Other food service activities | 340 | 2396 | 2396 | 1,131,806 |

| I56301 | Night clubs | 115 | 1726 | 1609 | 969,143 |

| I56302 | Bars and cocktail lounges | 1548 | 19,405 | 18,481 | 11,252,945 |

| I56303 | Café or coffee shops | 947 | 10,991 | 10,509 | 7,912,984 |

| I56302 | Other beverage serving activities, n.e.c. | 262 | 1104 | 1104 | 1,318,373 |

| Characteristics | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 152 | 49.84 |

| Female | 153 | 50.16 | |

| Age | Below 18 | 16 | 5.25 |

| 18–36 | 245 | 80.33 | |

| 37–55 | 39 | 12.79 | |

| Over 56 | 5 | 1.64 | |

| Frequency of Visit | Daily | 124 | 40.66 |

| A few times per week | 97 | 31.8 | |

| About once per week | 25 | 8.2 | |

| A few times per month | 31 | 10.16 | |

| About once a month | 24 | 7.87 | |

| Rarely | 4 | 1.31 | |

| Time of Visit | Breakfast | 56 | 18.36 |

| Lunch | 116 | 38.03 | |

| Snack | 88 | 28.85 | |

| Dinner | 45 | 14.75 | |

| Money Spent in Drive-through | PHP 200 and Below | 61 | 20 |

| PHP 200–PHP 400 | 182 | 59.67 | |

| PHP 400–PHP 800 | 54 | 17.7 | |

| PHP 800 and above | 8 | 2.62 |

| Latent Variables | Items | Measures | Supporting References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Appetite (SA) | SA1 | I was hungry during my last drive-through visit. | Lee and Kim [12] |

| SA2 | I have a strong desire to eat during my last drive-through visit. | ||

| Menu Options (MO) | MO1 | The fast food’s drive through has more options suited for me. | |

| MO2 | My preferred food was available during the time of my visit. | ||

| MO3 | I could find a suitable option easily. | ||

| Imagery Elaboration (IE) | IE1 | I imagined what the food would taste like. | Lee and Kim [12] |

| IE2 | I imagined the smell of the food. | ||

| IE3 | I imagined what the actual food would look like. | ||

| Vividness (VV) | V1 | The imagery shown in the menu board was clear. | Lee and Kim [12] |

| V2 | The imagery shown in the menu board was detailed. | ||

| V3 | The imagery shown in the menu board was vivid. | ||

| Convenience (CO) | CO1 | The menu board was easy to read. | Rydell et al. [15] |

| CO2 | The food items were easy to locate. | ||

| CO3 | The menu board is located within my eye level. | ||

| Order Accuracy (OA) | OA1 | I received the meal I ordered correctly. | |

| OA2 | The staff repeats my order for recap. | - | |

| OA3 | I received the meal I ordered completely. | ||

| Satisfaction (S) | S1 | The quality of food was excellent. | Mcneil and Young [42]; Ryu et al. [43]; |

| S2 | The service I receive has worked out as well as I thought it would. | ||

| S3 | I am satisfied with my decision to visit the drive-through. | ||

| Loyalty (L) | L1 | I will recommend this drive-through to other people who seek my advice. | Gallarza-Granizo et al., [44]; Wu and Mohi [45] |

| L2 | I will say positive things to my friends about this drive-through. | ||

| L3 | I will encourage other people to visit this drive-through. | ||

| Repurchase Intention (RI) | RI1 | I will keep visiting the drive-through in the future. | Dipietro et al. [46]; Konuk, F.A. [47]; Liu et al. [48] |

| RI2 | I am looking forward to visit drive-through. | ||

| RI3 | Regardless of how often I visit drive-through, I always look forward to visiting it again. |

| Latent Variables | Items | Cronbach’s α | Factor Loadings | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Composite Reliability (CR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Appetite (SA) | SA1 | 0.581 | 0.61 | 0.417 | 0.588 |

| SA2 | 0.68 | ||||

| Menu Options (MO) | MO1 | 0.769 | 0.61 | 0.333 | 0.599 |

| MO2 | 0.54 | ||||

| MO3 | 0.58 | ||||

| Imagery Elaboration (IE) | IE1 | 0.796 | 0.79 | 0.567 | 0.796 |

| IE2 | 0.80 | ||||

| IE3 | 0.66 | ||||

| Vividness (VV) | V1 | 0.824 | 0.87 | 0.658 | 0.852 |

| V2 | 0.78 | ||||

| V3 | 0.78 | ||||

| Convenience (CO) | CO1 | 0.823 | 0.80 | 0.604 | 0.820 |

| CO2 | 0.78 | ||||

| CO3 | 0.75 | ||||

| Order Accuracy (OA) | OA1 | 0.850 | 0.82 | 0.664 | 0.854 |

| OA2 | 0.70 | ||||

| OA3 | 0.91 | ||||

| Satisfaction (S) | S1 | 0.891 | 0.84 | 0.689 | 0.869 |

| S2 | 0.83 | ||||

| S3 | 0.82 | ||||

| Loyalty (L) | L1 | 0.891 | 0.82 | 0.729 | 0.890 |

| L2 | 0.86 | ||||

| L3 | 0.88 | ||||

| Repurchase Intention (RI) | RI1 | 0.917 | 0.85 | 0.787 | 0.917 |

| RI2 | 0.91 | ||||

| RI3 | 0.90 |

| Goodness of Fit Measures of the SEM | Parameter Estimates | Minimum Cut-Off | Recommended by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 0.879 | >0.80 | [50] |

| Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) | 0.851 | >0.80 | [50] |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.055 | <0.07 | [49] |

| Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | 0.946 | >0.90 | [49] |

| Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.938 | >0.90 | [49] |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.945 | >0.90 | [49] |

| Variables | Direct Effect | p Value | Indirect Effect | p Value | Total Effect | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA → MO | 0.58 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.58 | 0.001 |

| SA → VV | - | - | 0.38 | 0.001 | 0.38 | 0.001 |

| SA → IE | - | - | 0.46 | 0.001 | 0.46 | 0.001 |

| SA → CO | - | - | 0.47 | 0.000 | 0.47 | 0.000 |

| SA → OA | - | - | 0.29 | 0.001 | 0.29 | 0.001 |

| SA → S | - | - | 0.39 | 0.001 | 0.39 | 0.001 |

| SA → L | - | - | 0.30 | 0.001 | 0.30 | 0.001 |

| SA → RI | - | - | 0.24 | 0.001 | 0.24 | 0.001 |

| MO → V | 0.64 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.64 | 0.001 |

| MO → IE | 0.79 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.79 | 0.001 |

| MO → CO | 0.74 | 0.001 | 0.07 | 0.44 | 0.81 | 0.001 |

| MO → OA | - | - | 0.49 | 0.001 | 0.49 | 0.001 |

| MO → S | - | - | 0.68 | 0.001 | 0.68 | 0.001 |

| MO → L | - | - | 0.52 | 0.001 | 0.52 | 0.001 |

| MO → RI | - | - | 0.42 | 0.001 | 0.42 | 0.001 |

| VV → CO | 0.10 | 0.46 | - | - | 0.10 | 0.46 |

| VV → OA | 0.28 | 0.002 | - | - | 0.28 | 0.002 |

| VV → S | - | - | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.05 |

| VV → L | - | - | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| VV → RI | - | - | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| IE → OA | 0.40 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.40 | 0.001 |

| IE → SA | - | - | 0.18 | 0.001 | 0.18 | 0.001 |

| IE → L | - | - | 0.14 | 0.001 | 0.14 | 0.001 |

| IE → RI | - | - | 0.11 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.001 |

| CO → SA | 0.56 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.56 | 0.001 |

| CO → L | - | - | 0.43 | 0.001 | 0.43 | 0.001 |

| CO → RI | - | - | 0.35 | 0.000 | 0.35 | 0.000 |

| OA → SA | 0.45 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.45 | 0.001 |

| OA → L | - | - | 0.34 | 0.001 | 0.34 | 0.001 |

| OA → RI | - | - | 0.28 | 0.001 | 0.28 | 0.001 |

| S → L | 0.77 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.77 | 0.001 |

| S → RI | - | - | 0.62 | 0.001 | 0.62 | 0.001 |

| L → RI | 0.81 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.81 | 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prasetyo, Y.T.; Castillo, A.M.; Salonga, L.J.; Sia, J.A.; Chuenyindee, T.; Young, M.N.; Persada, S.F.; Miraja, B.A.; Redi, A.A.N.P. Factors Influencing Repurchase Intention in Drive-Through Fast Food: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Foods 2021, 10, 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10061205

Prasetyo YT, Castillo AM, Salonga LJ, Sia JA, Chuenyindee T, Young MN, Persada SF, Miraja BA, Redi AANP. Factors Influencing Repurchase Intention in Drive-Through Fast Food: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Foods. 2021; 10(6):1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10061205

Chicago/Turabian StylePrasetyo, Yogi Tri, Allysa Mae Castillo, Louie John Salonga, John Allen Sia, Thanatorn Chuenyindee, Michael Nayat Young, Satria Fadil Persada, Bobby Ardiansyah Miraja, and Anak Agung Ngurah Perwira Redi. 2021. "Factors Influencing Repurchase Intention in Drive-Through Fast Food: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach" Foods 10, no. 6: 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10061205

APA StylePrasetyo, Y. T., Castillo, A. M., Salonga, L. J., Sia, J. A., Chuenyindee, T., Young, M. N., Persada, S. F., Miraja, B. A., & Redi, A. A. N. P. (2021). Factors Influencing Repurchase Intention in Drive-Through Fast Food: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Foods, 10(6), 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10061205