Determinants and Prevention Strategies for Household Food Waste: An Exploratory Study in Taiwan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Method

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedure and Data Analysis

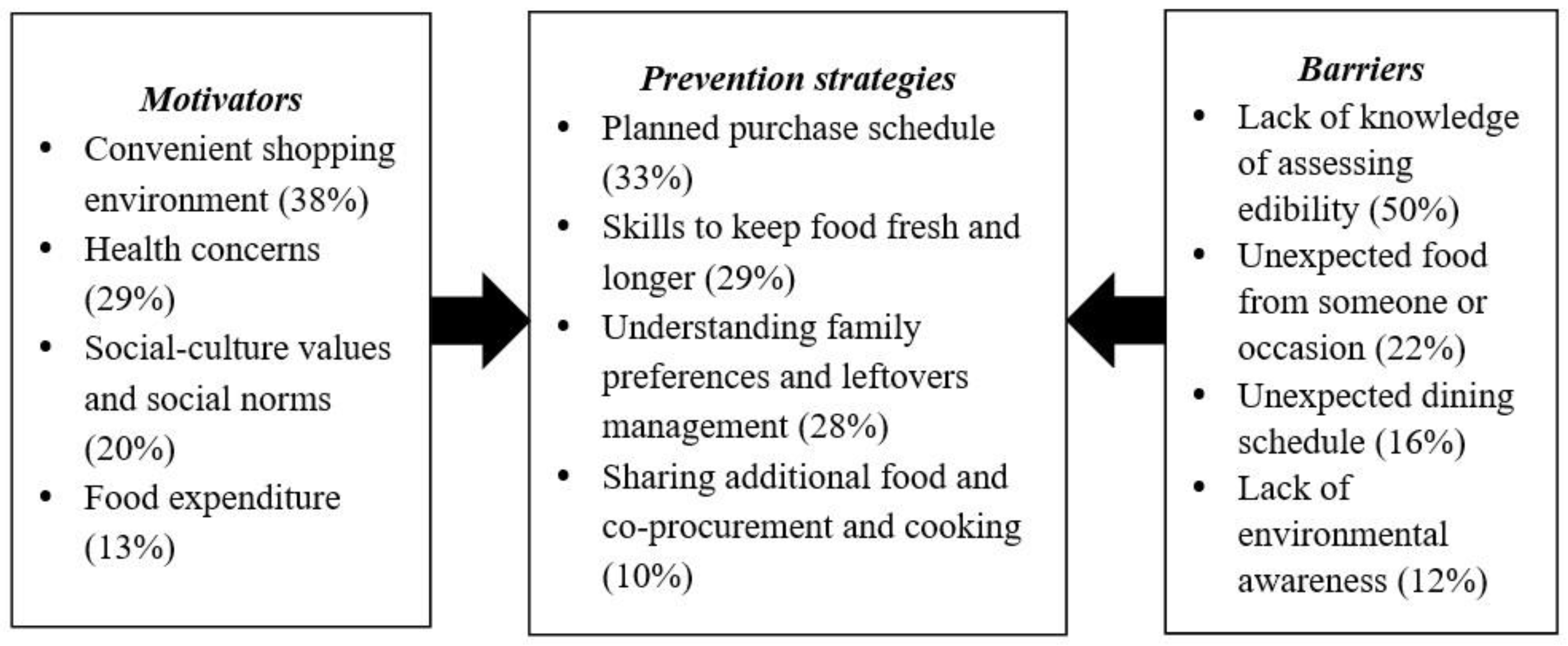

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Motivators to Reduce Food Waste

4.1.1. Convenient Shopping Environment (38%)

“Now I’m used to buying vegetables online…All the goods will be delivered to home. For example, the delivery man can buy what I need in an organic store, he can also go to the Binjiang Market to buy vegetables and fruits that I need, and then deliver to my home all together. It is very convenient and free from impulse purchase.”(A_11)

“When food is not enough, I go to the PX Mart chain. Because it’s so convenient in Taiwan, with three convenience stores or supermarkets just around the corner, I always feel that there is no need to stock up on food.”(A_7)

4.1.2. Health Concerns (29%)

“… Organic or safe food products with good quality usually come in small packages, it is fresher and easier to keep, and unlikely to have leftovers.”(A_8)

4.1.3. Socio-Cultural Values and Social Norms (20%)

“Every grain of rice is from hard work. I have known it since my childhood. I feel guilty towards the farmers if I do not finish my rice. Well, my grandparents were self-employed farmers, so I am especially concerned about it.”(A_11)

“Usually when I throw food away, I tell myself that I should not waste food like this all the time, otherwise, I will have nothing to eat in my next life. I just feel guilty.”(B_24)

4.1.4. Food Expenditure (13%)

“If I cannot use that much, why not buy a small package? I would rather buy a small package even if it is slightly more expensive than a large package. It is seemingly cost-effective. When little is used, a large portion will be left and thrown away. Isn’t it money-wasting and food-wasting?”(B_23)

4.2. Barriers to Minimizing Food Waste

4.2.1. Lack of Knowledge in Assessing Edibility (50%)

“If we think the food is not okay or not fresh, we will throw it away without hesitation.”(A_9)

“If fresh food such as meat or fish has been stored in the refrigerator for too long with its appearance seeming normal but with weird look or smell, I will tell my family members to throw it away.”(B_26)

4.2.2. Unexpected Food from Someone or Occasion (22%)

“For example, my daughter’s mother-in-law ordered pitayas from the place of origin and gave me these fruits. She sent me two boxes, with each box containing more than 50 pitayas, I then had two boxes of more than 100 pitayas. How can I finish them all by myself?”(A_6)

“It is not that the food we are given is not delicious, it is more that our family may not like it, or it is really not what we would eat as the food is overly sweet.”(B_25)

4.2.3. Unexpected Dining Schedule (16%)

“Sometimes my husband has to work overtime at short notice, or something comes up, he or our children cannot come home for dinner, then the food bought or cooked may be wasted.”(A_12)

4.2.4. Lack of Environmental Awareness (12%)

“Throwing food away does not really feel bad… To keep it in the refrigerator will waste power and taint other food with a bad smell. If nobody wants to eat it, then it should be thrown away.”(B_19)

“I think the kitchen waste should be used to feed pigs or sent somewhere to bury till it rots, through which, it may produce limited hazards to the environment.”(A_15)

4.3. Food Waste Prevention Strategies

4.3.1. Planned Purchase Schedule (33%)

“So my husband will buy… Sometimes his company will order some fruits or food together, but he usually won’t tell me and just bring them back. When I purchase the same food by accident, the doubled food becomes too much.”(A_10)

4.3.2. Skills to Keep Food Fresh and Longer (29%)

“Rhizomes, such as potatoes or sweet potatoes, will sprout after being stored for a long time. I’m used to processing them first, washing them, cutting them into the required size, and then storing them in the freezer.”(A_14)

“Some food can be stored in vacuum, including meat and seafood, such as anchovy larvae, shrimps and chicken, which can be stored in vacuum bags for a long time… Because food can be stored in vacuum bags for about half a year, it is safe as long as you finish it within the time limit.”(B_23)

4.3.3. Understanding Family Preferences and Leftover Management (28%)

“I know my children’s tastes and what they like. Basically, I will cook what they like and avoid what they don’t eat. I create new dishes containing their favorite ingredients.”(A_9)

“For example, if the salmon is pan-fried and not finished at the end, I will take off the meat and turn it into salmon fried rice on the next day… Or the fish will be stored in the refrigerator for use in other dishes later.”(A_4)

4.3.4. Sharing Additional Food and Co-Procurement and Cooking (10%)

“If I have a large quantity of fruits, I will keep some of them for my family, for the remaining part I usually will ask the surplus food community if anyone wants the fruits for free.”(B_20)

“For example, I always buy chicken in large quantities with my mother-in-law together from the same butcher shop. Before buying, I check how much chicken I need and then we will order and share the chicken together.”(A_11)

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme). UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- WRAP (The Waste and Resources Action Programme). UK Progress against Courtauld 2025 Targets and UN Sustainable Development Goal 12.3. Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Progress_against_Courtauld_2025_targets_and_UN_SDG_123.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; de Hooge, I.; Amani, P.; Bech-Larsen, T.; Oostindjer, M. Consumer-related food waste: Causes and potential for action. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6457–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mattar, L.; Abiad, M.G.; Chalak, A.; Diab, M.; Hassan, H. Attitudes and behaviors shaping household food waste generation: Lessons from Lebanon. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Administration Executive Yuan, R.O.C. General Waste Disposal Overview. Available online: https://www.epa.gov.tw/Page/8514DFCAB3529136 (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Identifying motivations and barriers to minimising household food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 84, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porpino, G.; Parente, J.; Wansink, B. Food waste paradox: Antecedents of food disposal in low income households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 101, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.V.; Young, C.W.; Unsworth, K.L.; Robinson, C. Bringing habits and emotions into food waste behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Statistics, Ministry of Economic Affairs, R.O.C. Overview of the Current Economic Situation (Special Topic: Retail Industry Development Status and International Comparison). Available online: https://www.moea.gov.tw/Mns/dos/bulletin/Bulletin.aspx?kind=23&html=1&menu_id=10212&bull_id=6124 (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Dobernig, K.; Schanes, K. Domestic spaces and beyond: Consumer food waste in the context of shopping and storing routines. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, T. Gifting, ridding and the “everyday mundane”: The role of class and privilege in food waste generation in Indonesia. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1444–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swilley, E.; Cowart, K.O.; Flynn, L.R. An examination of regifting. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivupuro, H.K.; Hartikainen, H.; Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.M.; Heikintalo, N.; Reinikainen, A.; Jalkanen, L. Influence of socio-demographical, behavioural and attitudinal factors on the amount of avoidable food waste generated in Finnish households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Blaming the consumer—Once again: The social and material contexts of everyday food waste practices in some English households. Crit. Public Health 2011, 21, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Zeidi, I.M.; Emamjomeh, M.M.; Asefzadeh, S.; Pearson, H. Household waste behaviours among a community sample in Iran: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, V.; vanHerpen, E.; Tudoran, A.A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Avoiding food waste by Romanian consumers: The importance of planning and shopping routines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, T.E.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A.D. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.A.; Spiker, M.L.; Truant, P.L. Wasted food: US consumers’ reported awareness, attitudes, and behaviors. PLoS ONE. 2015, 10, e0127881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Visschers, V.H.M.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters—A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelradi, F. Food waste behaviour at the household level: A conceptual framework. Waste Manag. 2018, 71, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callero, P.L. Role-identity salience. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1985, 48, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellini, B.; Parsons, E. Practising thrift at dinnertime: Mealtime leftovers, sacrifice and family membership. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 60, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr-Wharton, G.; Foth, M.; Choi, J.H.J. Identifying factors that promote consumer behaviours causing expired domestic food waste. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wansink, B.; vanIttersum, K. Portion size me: Plate-size induced consumption norms and win-win solutions for reducing food intake and waste. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2013, 19, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.; Meah, A. Food, waste and safety: Negotiating conflicting social anxieties into the practices of domestic provisioning. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 60, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fami, H.S.; Aramyan, L.H.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Alambaigi, A. Determinants of household food waste behavior in Tehran city: A structural model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 143, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebrok, M.; Boks, C. Household food waste: Drivers and potential intervention points for design—An extensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Naseer, A.; Shahid, M.; Shah, G.M.; Ullah, M.I.; Waqar, A.; Abbas, T.; Imran, M.; Rehman, F. Assessment of nutritional loss with food waste and factors governing this waste at household level in Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizeau, K.; vonMassow, M.; Martin, R. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponis, S.T.; Papanikolaou, P.A.; Katimertzoglou, P.; Ntalla, A.C.; Xenos, K.I. Household food waste in Greece: A questionnaire survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan, R.O.C. The Survey of Family Income and Expenditure. 2020. Available online: https://win.dgbas.gov.tw/fies/a12.asp?year=109 (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Manning, P.K.; Cullum-Swan, P. Narrative, content and semiotic analysis. Handb. Qual. Res. 1994, 29, 463–477. [Google Scholar]

- Holsti, O.R. Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.C.L. Grocery shopping, food waste, and the retail landscape of cities: The case of Seoul. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, B.; Liu, H.B. Food waste and the ‘green’ consumer. Australas. Mark. J. 2017, 25, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamerman, E.J.; Rudell, F.; Martins, C.M. Factors that predict taking restaurant leftovers: Strategies for reducing food waste. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjerris, M.; Gaiani, S. Household food waste in Nordic countries: Estimations and ethical implications. Etikk Praksis-Nord. J. Appl. Ethics 2013, 7, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Radzymińska, M.; Jakubowska, D.; Staniewska, K. Consumer attitude and behaviour towards food waste. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2016, 10, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, B.P.; Salet, W. The social meaning and function of household food rituals in preventing food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blichfeldt, B.S.; Mikkelsen, M.; Gram, M. When it stops being food: The edibility, ideology, procrastination, objectification and internalization of household food waste. Food Cult. Soc. 2015, 18, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganglbauer, E.; Fitzpatrick, G.; Comber, R. Negotiating food waste: Using a practice lens to inform design. ACM Trans. Comput. Interact. 2013, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Beyond the throwaway society: Ordinary domestic practice and a sociological approach to household food waste. Sociology 2012, 46, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Binning, gifting and recovery: The conduits of disposal in household food consumption. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2012, 30, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secondi, L.; Principato, L.; Laureti, T. Household food waste behaviour in EU-27 countries: A multilevel analysis. Food Policy. 2015, 56, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, F.; Di Donato, P.; Covino, D.; Poli, A. Food waste and bio-economy: A scenario for the Italian tomato market. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 227, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangherlin, I.C.; Barcellos, M.D. Drivers and barriers to food waste reduction. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2364–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Theme | Method | Respondents | Factors | Management Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | Mealtime, leftovers, sacrifice and family membership | Ethnographic study | 20 households living in UK. The age range was early 30 s to early 50 s. | Moral norm, unpredictable eating patterns and preferences, lack of acceptance of leftovers | Managing leftovers, proper and systematic storage practices |

| [6] | Motivations and barriers to minimizing household food waste | Qualitative study | 15 UK household food purchasers. The age range was 21 to 75. | Waste concerns, doing the ‘right’ thing, a ‘good’ provider identity, minimizing inconvenience, exemption from responsibility | Food management |

| [19] | Food waste behaviors | The ‘lenses’ of different academic disciplines | Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP) (UK) | Attitude, norm, habit, emotion, awareness | Planning, shopping, storing, cooking knowledge |

| [17] | The importance of planning and shopping routines | Questionnaire survey | 244 Romanian consumers. The mean age of the participants was 38 years, and 86% of respondents were female. | Moral attitudes, waste concerns, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control | Planning and shopping routines |

| [3] | Food waste causes and potential for action | Literature review and expert interviews | Consumer in the U.S. and the U.K. | Good provider identity, environmental awareness, doing the ‘right’ thing, lack of acceptance of leftovers | Planning of food shopping and meals, shopping list, proper and systematic storage practices, expiration date monitoring, assessing edibility, knowledge about shelf-life and how to extend it |

| [8] | Household food waste reduction | Questionnaire survey | 279 UK residents. The mean age of the participants was 35 years, and 80% of respondents were female. | Attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, self-identity, anticipated regret, moral norm, descriptive norm | No mention |

| [18] | Determinants of consumer food waste behavior | Questionnaire survey | 1062 Danish consumers. The mean age of the participants was 48 years, and 53% of respondents were female. | Injunctive and moral norms, attitudes towards food waste, perceived behavioral control | Planning of food shopping and meals, shopping list, shopping routines, portion control, managing leftovers |

| [21] | Motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households | Questionnaire Survey | 796 Swiss-German residents. The mean age of the participants was 57 years, and 59% of respondents were female. | Attitude, subjective norm, personal norm, knowledge, household, planning habits, the good provider identity, perceived health risk | Food storage knowledge, knowledge about shelf-life and how to extend it |

| [30] | Household food waste | Literature review | Western countries | Awareness and attitudes, social norm, health perception, good provider identity, eating preferences, lifestyles | Planning, storing, portion control, managing leftovers, assessing edibility, knowledge about shelf-life and how to extend it |

| [33] | Household food waste | Questionnaire Survey | 500 Greek households. The mean age of the participants was 36 years, and 60% of respondents were female. | Shopping habits, eating preferences | Proper and systematic storage practices, expiration date monitoring, portion control |

| [9] | Food waste behavior | A temporally lagged design | 172 UK consumers. The median age of participants was in the range of 50–59, and 59% of respondents were female. | Subjective norm, attitude towards food waste, perceived behavioral control, habitual food waste behavior, negative emotion | No mention |

| [4] | Attitudes and behaviors shaping household food waste generation | Questionnaire Survey | 1264 Lebanon households. 86% of respondents were female. | Awareness, eating-out in restaurants, buying special offers, moral norm | Managing leftovers |

| [22] | Household food waste practices and their policy implications | Systematic review | Europe | Environmental awareness, norms, attitudes, perceived behavioral control, health perception, good provider identity, eating preferences, minimizing inconvenience, time constraints; unplanned events, eating-out, inadequate communication between household members | Knowledge about planning, shopping, storing, and cooking |

| Location | Code | Gender | Household Size | Age | Occupation | Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taipei City | A_01 | F | 3 (2 parents/1 child) | 42 | Office worker | University |

| A_02 | F | 4 (2 parents/2 children) | 34 | Housewife | University | |

| A_03 | M | 6 (2 parents/1 child/1 grandmother/1 great-grandmother/1 servant) | 33 | Administration staff | Graduate school | |

| A_04 | F | 3 (2 parents/1 child) | 35 | Office worker | University | |

| A_05 | M | 3 (2 parents/1 child) | 40 | Administration staff | University | |

| A_06 | F | 7 (2 parents/1 nephew/2 grandparents/2 servants) | 63 | Company owner | College | |

| A_07 | F | 4 (2 parents/2 children) | 34 | Store owner | University | |

| A_08 | F | 3 (2 parents/1 child) | 44 | Bakery owner | College | |

| A_09 | F | 3 (2 parents/1 child) | 32 | Housewife | University | |

| A_10 | F | 4 (2 parents/2 children) | 42 | Housewife | University | |

| A_11 | F | 4 (2 parents/2 children) | 40 | Housewife | University | |

| A_12 | F | 4 (2 parents/2 children) | 44 | Housewife | College | |

| A_13 | F | 4 (2 parents/2 children) | 38 | Housewife | University | |

| A_14 | F | 3 (2 parents/1 child) | 66 | Housewife | College | |

| A_15 | F | 4 (2 parents/2 children) | 68 | Housewife | College | |

| A_16 | F | 4 (2 parents/1 child) | 37 | Office staff | University | |

| A_17 | F | 4 (2 parents/2 children) | 32 | Cook | College | |

| New Taipei City | B_18 | F | ordinary day: 2 (2 parents) holiday:14 (2 parents/5 children/7 grandchildren) | 52 | Cleaning lady | Vocational high school |

| B_19 | F | 5 (2 parents/3 children) | 44 | Teacher | University | |

| B_20 | F | 3 (couple/1 mother-in-law) | 42 | Administration staff | University | |

| B_21 | F | 5 (2 parents/3 children) | 50 | Factory worker | Vocational high school | |

| B_22 | F | 3 (2 parents/1 child) | 54 | Administration staff | University | |

| B_23 | F | 6 (2 parents/1 son/1 daughter-in-law/2 grandchildren) | 48 | Secretary | High school | |

| B_24 | F | 5 (2 parents/3 children) | 40 | Administration staff | Graduate school | |

| B_25 | F | 4 (2 parents/2 children) | 39 | Office worker | Graduate school | |

| B_26 | F | 4 (2 parents/2 children) | 43 | Office worker | Graduate school | |

| B_27 | F | 3 (2 parents/1 child) | 41 | Administration staff | Graduate school |

| Themes/Interview Questions | References |

|---|---|

| 1. Food purchasing practices (e.g., How do you shop for food for your family? Can you describe a typical food shopping trip? How do you decide what food you are going to buy? How much do you spend on food in an average week? How often do you usually do your main shopping trip? How often do you usually do a smaller ‘‘top up’’ shopping trip?) | [6,7,11,17,22,30] |

| 2. Food storage practices (e.g., Can you describe a typical food storage process after you shop? Can you share special preservation methods to reduce food spoilage?) | [7,11,22,30] |

| 3. Food preparation and cooking (e.g., How do you decide how much food you cook each time? How do you plan the meals you cook every time? What is your attitude towards the leftovers? How do you deal with the leftovers?) | [7,11,22,30] |

| 4. Food waste behaviors (e.g., Tell me about your thoughts and feelings regarding throwing food away. What caused you to throw away the food? Can you describe why you think this happened? How did you decide that food should be discarded? How much food do you throw away from what you buy in a regular week?) | [6,17,22,30] |

| 5. Methods and strategies for the reduction of food waste (e.g., What are your food management practices? What are the most effective ways to avoid or reduce the amount of food thrown away? Are there any obstacles that will prevent you from reducing food waste? How will you deal with this problem?) | [6,17,22] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teng, C.-C.; Chih, C.; Yang, W.-J.; Chien, C.-H. Determinants and Prevention Strategies for Household Food Waste: An Exploratory Study in Taiwan. Foods 2021, 10, 2331. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10102331

Teng C-C, Chih C, Yang W-J, Chien C-H. Determinants and Prevention Strategies for Household Food Waste: An Exploratory Study in Taiwan. Foods. 2021; 10(10):2331. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10102331

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeng, Chih-Ching, Chueh Chih, Wen-Ju Yang, and Chia-Hui Chien. 2021. "Determinants and Prevention Strategies for Household Food Waste: An Exploratory Study in Taiwan" Foods 10, no. 10: 2331. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10102331

APA StyleTeng, C.-C., Chih, C., Yang, W.-J., & Chien, C.-H. (2021). Determinants and Prevention Strategies for Household Food Waste: An Exploratory Study in Taiwan. Foods, 10(10), 2331. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10102331