Abstract

Many academic and research institutions today maintain multiple types of institutional repositories operating on different systems and platforms to accommodate the needs and governance of the materials they house. Often, these institutions support multiple repository infrastructures, as these systems and platforms are not able to accommodate the broad range of materials that an institution creates. Announced in 2017, the Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) Libraries implemented a new repository solution and service model. Built upon the Figshare for Institutions platform, the KiltHub repository has taken on the role of a traditional institutional repository and institutional data repository, meeting the disparate needs of its researchers, faculty, and students. This paper will review how the CMU Libraries implemented the KiltHub repository and how the repository services was redeveloped to provide a more encompassing solution for traditional institutional repository materials and research datasets. Additionally, this paper will summarize how the CMU University Libraries surveyed the current repository landscape, decided to implement Figshare for Institutions as a comprehensive institutional repository, revised its previous repository service model to accommodate the influx of new material types, and what needed to be developed for campus engagement. This paper is based upon a presentation of the same title delivered at the 2018 Open Repositories Conference held at Montana State University in Bozeman, Montana.

1. Introduction

Over the last two decades since the creation of the DSpace repository platform by MIT and Hewlett-Packard in 2002 [1], academic and research institutions have developed and implemented a wide range of institutional repositories. Increasingly, institutional repositories have become a dynamic tool for scholarly communication, and a necessary resource for managing institutional research and knowledge [2]. This has included multiple repositories focused on maintaining and housing the wide range of materials that required unique environments and needs to accommodate them digitally. Likewise, some repositories were designed for set purposes, such as Electronic Thesis/Dissertation (ETD) repositories, open access publication repositories, and research data repositories.

As the creation of research data has increased, so too has the need to support its creation and management. Michael Witt noted that academic and research libraries have taken a more active role in the research data management services and infrastructure provided by institutions to handle the increase in data output [3]. The expansion of roles for academic libraries now has often led to their expanded integration in the research cycle of their institutions. Witt further elaborates this point, detailing that libraries can collaborate with their campus communities to understand what tools, services, and support will be necessary to support services for data [3]. As Tenopir et al. explained in their 2015 study, this can lead to libraries becoming invested partners in all aspects of the research process, from data collection to publication, and to the preservation of research outputs [4].

In his 2002 SPARC position paper, Raym Crow noted that an Institutional Repository (IR) could be implemented to demonstrate the visibility, reach, and overall significance of an institution’s research, thereby providing both short-term and long-term benefits [5]. In contrast, Clifford Lynch expanded upon the notion of how an IR could be defined beyond a single entity or service. In his 2003 ARL briefing, Lynch described an IR not just as a single entity or service, but rather as “a set of services that a university offers to the members of its community for the management and dissemination of digital materials created by the institution and its community members” [6]. More recently, the Research Data Alliance’s (RDA) Data Foundations and Terminology Working Group presented a more defined definition of a repository, especially with the involvement of research data. RDA defines a repository as “a Repository (aka Data Repository or Digital Data Repository) is a searchable and queryable interfacing entity that is able to store, manage, maintain and curate Data/Digital Objects. A data repository provides a service for human and machine to make data discoverable/searchable through collection(s) of metadata” [7].

As institutional and research repositories have grown in adoption and usage, the conceptual thinking of what a repository is has also grown. This new rethought includes the range of different repository platforms and services models. Just as repositories can be defined as a dynamic service and tool, the overall scholarly communication ecosystem can also be defined as a set of related and sometimes interrelated tools and services designed to create, maintain, publish, disseminate, and assess the data and other scholarly outputs created during the research lifecycle.

Founded in 1900 by Steel magnate and philanthropist, Andrew Carnegie, Carnegie Mellon University is an R1: Doctoral Universities—Very high research activity private nonprofit research university located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania [8]. CMU is home to nearly 1400 faculty and 14,000 students representing seven academic colleges, ranging from business, computer science, fine arts, engineering, humanities and social sciences, information systems and public policy, and the sciences [9]. With campuses located nationwide in Pittsburgh, New York, Silicon Valley, and globally with campuses in Qatar, Rwanda, and Australia, CMU is well represented and situated within the global communities of research and practice. CMU students represent 109 countries, with faculty also representing forty-two countries. The CMU Alumni network includes over 105,000 thousand living members representing 145 different countries [9]. With such high and dynamic focuses in both the arts and STEM, and with such a large and diverse global reach, the research data and other scholarly outputs produced by its campus community range in diversity as well.

In 2015, Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) began evaluating its own institutional repository platform and services models. CMU concluded that a new repository was needed to support the wide range of materials it produces, including research data and other forms of scholarly outputs. Beyond focusing on the repository and service models, CMU also focused on the overall scholarly communication ecosystem. This additional focus included examining and considering the expanded role the IR. CMU sought a partnership with open data repository platform Figshare, in examining the development of a new repository that could comprehensively serve an academic institution or research entity by serving the multiple needs required of a new generation of repositories, while also expanding the role a repository could play in the broader research lifecycle for the individual and the institution. This paper is based upon a presentation of the same title delivered at the 2018 Open Repositories Conference held at Montana State University in Bozeman, Montana [10].

3. Repository Landscape at Carnegie Mellon University

Prior to 2017, the University Libraries at CMU maintained only two repositories. These two repositories were focused on repository services for archival and special collection materials in its archival repository, and materials were traditionally housed in an IR in the traditionally focused institutional repository. At this time, there was not a repository service designated for research data that could adequately address the needs of researcher’s data.

The mission of the University Archives at CMU is to document, preserve, and provide access to the records documenting life at CMU and the contributions of its students and faculty [22]. Implemented in 2011, the University Archives maintains an archival repository for its digital collections. The archival repository is built upon the hosted platform Knowvation (formerly known as ArchivalWare) offered by Progressive Technology Federal Systems, Inc. (PTFS) [23]. The digital collections at CMU house twenty-six digital collections from the University Archives. These digital collections include digitized campus publications; large archival collections, such as the Herb Simon Papers; rare books from the Posner Collection; projects digitized in partnership with the Carnegie library of Pittsburgh and the Heinz History Center; and fully-digitized archival collections made available for researcher access [24].

Built upon the Digital Commons hosted IR platform and publishing platform offered by bepress (now Elsevier), Research Showcase served as the IR for CMU from October of 2008 to June 2018 [25]. As a traditionally focused IR, Research Showcase provided online access to materials produced by members of the CMU faculty, staff, and students. These materials included green and gold open access versions of published works, gray literature such as white papers and technical reports, academic posters, conference papers, presentation slide decks, undergraduate honors theses, and graduate student electronic theses and dissertations.

While used primarily as a traditionally focused IR, Research Showcase was lightly used as a publishing platform. Between 2009 and 2016 with the publishing of Volume 7 Issues 3, the Journal of Privacy and Confidentiality was published on Research Showcase through the relationship of the journal and one of its three founding editors, the late Professor Stephen Fienberg [26]. While the journal was published on Research Showcase, it did not utilize the journal publishing module built within Digital Commons. Since the publication of Volume 7 Issue 3, the journal has moved its operations to the Labor Dynamics Institute at Cornell University [27].

In alignment with the 41.1% of institutions examined by Ayoung Yoon and Teresa Shultz in their 2017 content analysis study of academic library websites [28], the University Libraries began offering research data consultation services around 2013 with no data repository in place. These consultation services included data management plan development, search, reuse, sharing methods, and reviews of required or appropriate venues for data publishing.

4. Evolution of Repository Services at CMU

With the expansion for data sharing in 2003 with the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation in 2011, academic research libraries explored how to provide the necessary technical infrastructure and services necessary to aid researchers in these new mandated requirements [3,29]. Neither the archival repository nor the traditional IR was designed to handle the complexity of research datasets. That being said, the need to have a data repository service had not been a prior requested need or service. The need for such a repository at CMU changed in February 2013 with the U.S. White House Office of Science Technology Policy (OSTP) memorandum, which directed federal agencies with more than $100 million in research and development expenditures to prepare policies to make federally funded research results publicly available within 12 months of publication [30].

In February of 2015, the University Libraries were asked if they could assist in making a research dataset publicly available to assist a researcher in complying with their funder’s data sharing requirements. The University Libraries was able to assist the faculty member, but with an unconventional and short-term solution. The University Libraries utilized the archival repository to deposit the dataset as a stop-gap solution. This dataset has since been migrated to the new repository [31]. This use case and stop-gap solution provided the basis and laid out the needs for a new repository platform that would meet the needs for data publishing and sharing across campus. It also presented an opportunity to evaluate the current repository landscape at CMU, and ascertain if a new solution could be implemented to meet the growing needs not currently being met for emerging forms of scholarly outputs, but also to better meet the needs being met by the current repository solution.

Published in the fall of 2015, the 2025 Carnegie Mellon University Strategic Plan included a strategic recommendation for the creation of a 21st century library that would serve as a cornerstone of world-class research and scholarship from CMU. One important goal tied to this strategic recommendation was to develop services and infrastructure that would “steward the evolving scholarly record and champion new forms of scholarly communication” [32]. The University Libraries took this goal, and began evaluating repository platforms and repository service models.

Prior to the Publication of the 2025 CMU Strategic Plan, the University Libraries published an internal report in early 2015 that was based upon its evaluation of current repository solutions for a new institutional repository. The report covered several common discussions and evaluations similarly conducted by peer institutions who had evaluated their own institutional repository or data repository needs [33]. This internal report on “CMU’s institutional repository, research data repository, and digital collections platforms” focused on determining the requirements for a replacement IR platform, and a potential data repository [34]. Additionally, the report including a review of the challenges and issues a new repository platform would present to the University Libraries from a technical, organizational, and service perspectives.

The report presented some of the internal use cases and requirements that were based upon current capabilities provided by Digital Commons, which included the ability for self-deposit and deposit by proxy, arrangement and description of content by academic hierarchy, ability to deposit content with various file formats and their accompanying metadata, and the ability to monitor usage statistics (e.g., altmetric data, views, and downloads). Likewise, the report presented several aspirational features and capabilities, including a system that could generate DOIs during the submission and publishing workflows, ability to accept larger (>1 GB) files, and a system that could provide users with a way to preview content before being downloaded.

The report presented an evaluation of possible repository solutions, based upon currently known systems and implementation examples from peer and aspiration peer institutions using similar systems. The systems that were evaluated included Fedora, DSpace, EPrints, Islandora, Hydra (now known as Samvera), Invenio (formerly known as CDSware), SobekCM, and Zentity from Microsoft [34]. Each platform evaluation included a summary of its background, history, technical overview, features, and a summary of implementations found at other institutions. The report concluded with presenting a possible plan for implementation of each proposed system, as well as a discussion of challenges and concerns each new system would present. Overall, the report found that while Digital Commons lacked some of the needs and technical capabilities necessary for the data repository, it possessed several features that were useful and beneficial to users and administrators. Similarly, while several open source platforms offered potential solutions that met the proposed data repository needs, they presented their own challenges. With many of the open source solutions being written in various software languages, the University Libraries lacked the personnel with the background and knowledge of these new software languages. Likewise, these systems would present additional needs for hosting and infrastructure that the University Libraries could not sufficiently provide at that time.

At the same time, the internal report on institutional repository evaluations and possible data repository solutions was being developed, and the University Libraries became aware of the Figshare for Institutions platform as a possible data solution, which had not included in the original internal report given its timing and availability. Because the University Libraries lacked the technical knowledge to maintain an open source repository solution such as those discussed in the institutional repository report, utilizing a licensed repository solution was appealing for several reasons. First, as already discussed, the University Libraries lacked the technical expertise to manage and support the most commonly used open source solutions. Secondly, the operational costs for the new repository, as compared to the costs associated with the current institutional repository, which was also a licensed solution, were commensurable. Lastly, the University Libraries already had a critical need for a repository, and waiting to hire necessary personnel would have extended the solution beyond the expectation for results from campus leadership.

Using Figshare for Institutions as the data repository solution also appealed to the University Libraries because of what the product would provide functionally and technically. As an open platform available freely for anyone to use via figshare.com, it was a repository solution that campus community members would already potentially be accustomed to using. Upon examining the data published publicly, the University Libraries identified several datasets deposited by campus faculty and graduate students. This meant that the University Libraries could utilize the potential name recognition and workflows to highlight that their new repository would not be something that users would not be accustomed to used. By highlighting that the CMU repository would be “powered by figshare,” the University Libraries could utilize Figshare’s relationship with the campus community to provide its own repository services.

With a metadata record based upon Dublin-Core, the submission process required to make deposits presented a simple, straightforward workflow that would not overburden users. Lastly, like figshare.com, Figshare for Institutions possessed several avenues for interoperability and integrations to necessary research mechanisms. Users were not restricted from uploaded certain file formats, and they could conduct deposits through either the systems user interface, desktop plugin, or through the platforms open API [35,36]. Through its integrations with GitHub and DOI registering authorities EZID and DataCite, users could easily sync their current workflows to push datasets from a working space to the repository to be published with a recognized data citation and DOI for future citability [37]. Lastly, because Figshare for Institutions was a hosted repository solution, with storage maintained by Amazon Web Services, the technical infrastructure necessary for hosting the repository and its materials would not be left to the University Libraries to manage or maintain [38].

The internal report revealed that further evaluation of repositories was needed. This led to the formation of the Digital Repository Task Force (DRTF) within the University Libraries in October of 2015. In similar groups organized at other institutions, such as the task force developed at the University of Minnesota in the development of the Data Repository for the University of Minnesota “DRUM”, the University Libraries’ task force was comprised of librarians, archivists, and staff from around the University Libraries [29]. All identified team members possessed some level of knowledge or expertise in repositories, and were also identified as individuals who would have an invested interest in the repository once implemented. The DRTF included members from the Archives, Research Data Management unit, Scholarly Communications and Research Curation unit, Libraries IT, and postdoctoral fellows from the University Libraries Council on Library and Information (CLiR) postdoctoral program.

The tasks force’s goal was to take the information gathered from the previous internal report and combine it with new analyses on a new repository solution. Part of this goal was also to define a new repository and related service that could be targeted towards multiple and diverse audiences. As the University of Minnesota 2015 study found, this diverse audience could include researchers/data authors, PIs, campus administrators, and institutional research stakeholders [29].

As the University Libraries further evaluated repository solutions, the university also began evaluating the Research Information Management (RIM) system landscape. From October of 2015 to May of 2016, the university evaluated several RIM systems. This included Pure from Elsevier, Converis from Clarivate, and Symplectic Elements from Digital Science. The university chose to not evaluate Digital Measures from Watermark, because it was a solution already implemented at an individual college/school level. The College of Engineering and the Tepper School of Business both had their own licenses to Digital Measures. Both units were ready to evaluate a new RIM system, especially if that new system was going to be maintained and supported university-wide.

The evaluation of the RIM landscape involved a number of individuals from around the university, and could have been described as a “collaboration of stakeholders” [3]. The evaluation was conducted by members of the University Libraries, campus administration, college and school deans and associate deans, members of the faculty, campus computing services, Vice-Provost for research office, sponsored programs, and the general counsel’s office. All members of the RIM evaluation group were invested in the way in which research conducted at CMU was developed, completed, reported, verified, published, and preserved.

Beyond focusing on just a RIM, the campus RIM evaluation group also looked at other systems, tools, platforms, and services that could have a potential connection to the RIM, which included new repository system(s). After evaluating each of the RIMs, and several other potentially interrelated systems, the university chose to select Symplectic Elements as its RIM in February 2017. In addition to selecting Symplectic Elements, the university also chose to license a suite of services from Digital Science. This included Altmetric.com and Dimensions. The University also decided that Figshare’s Figshare for Institutions Repository Platform would become the new repository platform. But beyond utilizing Figshare as a data repository, it was decided that the new Figshare for Institutions Repository would also become the new institutional repository platform. This decision was not just a matter of setting forth a plan, but also included the investment and purchasing of these new services, which came from newly added funds provided by the Provosts office. This new repository, including its related services, would not just be a grassroots effort of the University Libraries. The repository should be both a top-down- and bottom-up-focused endeavor [4]. A key factor found in the study conducted by Lagzian, Abrizah, and Wee was the importance placed on management support of the IR [39]. The purchase of the new repository was not be just an investment made by the University Libraries, but an investment that was integral to the university, thus providing the University Libraries the necessary means to expand research support and services across the university.

CMU and Figshare were both very interested in exploring how the repository could be implemented beyond as a traditional data repository. During the examination of Figshare for Institutions as a data repository, the University Libraries recognized that the technical and functional needs necessary to implement a new institutional repository were already present in Figshare for Institutions. Additionally, because the Figshare repository would be treated as a repository at an institution, the data would be published and arranged in collections and series that would reflect the organizational structure of the academic colleges, schools, departments, researcher centers, and institutions at CMU, which is exactly how the IR was already arranged. Because figshare.com already permitted users to submit any file format, many users were already depositing materials that, from a collection development perspective, would have been deposited to an IR. Lastly, Figshare for Institutions possessed the functional and technical capabilities to ensure that the University Libraries could implement curation workflows to ensure that the content published in the repository were reflective of the research and scholarship of the CMU community, and were permitted for open dissemination in an open access repository. With these common functions and capabilities, the University Libraries questioned why users had not previously thought to use Figshare for Institutions as the IR. With the repository serving as both a data repository and institutional repository, CMU referred to its new repository as the comprehensive repository.

This new comprehensive repository would offer a robust and reliable place to curate research data and other scholarly outputs; ensuring compliance with open data and open access mandates from funders and publishers and promoting a culture of open and sharing research and scholarship from CMU. Additionally, this consolidated repository service would decrease the number of locations campus partners would have to interact with for depositing their content. By limiting the number of repositories and interaction points by developing a new repository that combined common and parallel goals, the University Libraries could define this new service in a way that prevented offering multiple repositories with overlap, thereby creating points of competition, such as those seen at the University of Minnesota and Penn State University [40].

There were several use cases that Digital Science and CMU wanted to jointly explore through taking advantage of the interoperable nature of these systems. These use cases and shared interests moved the relationship between CMU and Digital Science beyond a traditional licensed product relationship between vendors and providers, and towards a relationship that wanted to explore and design possible solutions for these use cases as partners. In February of 2017, CMU and Digital Science announced the creation of a strategic development partnership agreement [41]. Through the implementation of a suite of products from the Digital Science portfolio, CMU unveiled a broad solution to capture, analyze, and showcase the research and scholarship of its faculty, staff, and students through using continuous, automated methods of capturing data from multiple internal and external sources. This include publication data and associated citations, altmetric data, grant data, and research data itself. This partnership and common goals provided CMU the mechanisms to provide its faculty, funders, and decision-makers with a more accurate, timely, and holistic examination of the institution’s research and outputs. Through the shared goal of championing new forms of scholarly communications, CMU brought together these services and tools from Digital Science, alongside other services solutions from within the university and other external service providers, to develop its own scholarly communications ecosystem—a scholarly communications ecosystem that would rely heavily on the new comprehensive repository platform from Figshare.

5. The KiltHub Repository

Having a repository built upon the Figshare for Institutions platform presented both advantages and challenges to the University Libraries. First, the Universities Libraries had known from earlier interactions and meetings with faculty and students that many were already familiar with the service provided by figshare.com. This service offering included the ability to deposit a wide range of file types, with many of these file types having built-in file previewers and manipulation tools and plug-ins built into the user interface. Additionally, from a data creation standpoint, figshare already had integration with GitHub, which allowed users to pull data from their GitHub accounts and publish the data to figshare. Beyond traditional publishing, a distinguishing trait and capability is the ability to version data during the data publishing process [42]. Figshare already had the functionality to allow users to version their data, regardless if this was initiated directly through the user interface, or through the versioning of data provided from the user’s GitHub account integration.

After the announcement of the strategic partnership, the University Libraries knew it needed to name and brand its new repository to reflect its ties to CMU. Simply calling the repository “Figshare @ CMU” or the “CMU Figshare Repository” would not work. While a simple solution, these names wouldn’t allow the university to market the repository as a true repository solution and service offered by CMU. Marketing a repository in a way that will highlight its capabilities, services, value, and impact is crucial to ensure campus awareness and to develop the necessary incentives to internal and external stakeholders [43]. The name needed to reflect that it was more than just a portal to figshare.com filtered to CMU material. Likewise, it was important that the name convey the intended nature of the new platform; being a comprehensive repository that combined a data repository and traditional IR into one single repository.

With Figshare traditionally being seen as a data repository, it was important that users understand that the new repository would be much more. The repository would have more than one single primary focus. This new repository would account for both Lynch and Crow’s definition of an IR. Novak and Day described these definitions as the “thesis and antithesis” to the two foundational principles of IRs as primarily serving the needs for green open access or new forms of digital scholarship [44]. KiltHub’s focus would be to serve as a repository that reflected both perspectives. By reflecting both foundational perspectives, KiltHub would serve as a proposed solution to what Clifford Lynch described in the introduction to Making Repositories Work, as the “unresolved dialectic” [45].

Lynch’s dialectic could also be carried through between figshare.com and Figshare for Institutions. While this new repository would be “powered by Figshare,” it would provide more than what users experienced from the public figshare.com service. It would reflect the capabilities of a repository maintained at an institution, including the additional layers of curation services provided by repositories from similar universities. While having a unique repository built on a platform that many counterparts had not adopted, KiltHub’s capabilities and services would be comparable to those seen as other institutions. When compared to the six repositories, which were compared by Johnston, Carlson, and Hswe in their 2017 study from the Data Curation Network, KiltHub would provide the same types of pre-ingest curation, deposit support and mechanisms, approval, publication, and post-ingest curation services [40].

Additionally, CMU wanted the repository to fall into the traditional “institutional repository” category. This could cause the repository to be categorized with the same associated pitfalls and limitations linked with a traditional IR. To achieve these goals, the University Libraries organized a naming contest for the new repository. Between February and March 2017, the University Libraries ran a campus-wide naming contest for the repository [46]. The contest was open to all faculty, staff, and students. A prize was offered for the winning entry of five hundred dollars towards a research or travel grant (for faculty) or a piece of technology of equal value from the campus computing store. Entrants were required to submit an original and distinctive name. Entrants could also create multiple unique name entries. Although not required to enter the contest, entrants were also encouraged to submit taglines and proposed logos to use for marketing and promotional purposes. Once the entrance period had ended, a selection committee was formed. The selection committee was comprised of representatives of the University Libraries, the Faculty Senate University Libraries Committee, and students. In total, the contest received 51 entries from faculty, staff, and undergraduate, graduate, and PhD students representing the Pittsburgh, Silicon Valley, and Qatar campuses. The winning application was submitted by an Associate Teaching Professor of Hispanic Studies from the Department of Modern Languages within the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences. On 13 April 2017, during National Library Week, the University Libraries announced the new name of its repository—KiltHub [47].

The KiltHub name was selected for two main reasons: First, the name reflected the Scottish connection the university has maintained with its founder. Second, the name alluded to the central “hub-like” nature repositories can serve by collecting and disseminating research data and other scholarly outputs of the entire institution. As the comprehensive repository to CMU, the KiltHub repository “collects, preserves, and provides stable, long-term global online access to a wide range of research data and scholarly outputs created by the faculty, staff, and students of Carnegie Mellon University in the course of their research and teaching” [47]. In addition to implementing the repository, the University Libraries developed a parallel information portal [47]. The information portal provides additional information, contact information, and several user guides. The user guides cover several topics, such as using the repository, depositing scholarly outputs, preparing data, and completing the README.txt file, which are required for each data deposit submission.

6. KiltHub Repository Teams

As researchers have become more accustomed to sharing their data, working with these materials has also matured. As data and other forms of digital scholarship and research expand, librarianship to support these objects and activities will also mature [3]. While systems will need to mature, the repository service must rely upon those providing these services. As Rowena Cullen and Brenda Chawner discuss in their 2011 study, the “build it they will come” philosophy has never been truly justified [48]. The repository is more than its technology. There has to be a strong supporting infrastructure of support services, including support personnel, to enrich the repository experience and its usefulness to its users.

To maintain a repository with such a dynamic purpose, and to provide a suite of repository services, a service model utilizing three sets of teams of individuals from within the University Libraries was implemented. The service model adopted by these teams of individuals would need to scalable and manageable for the university libraries [29]. The composition of the KiltHub Repository Teams was reflective of the findings of the 2014 research data services survey from the DataOne project, which highlighted the usage of a diverse set of individuals and teams to provide these services [4]. As Tenopir et al. discussed, while the need to grow the core data services team was core to the research data services component of the repository, the larger bulk of expansion of research data services at CMU have been around shifting current library faculty and staff in association to research data services, as well as depending upon individuals having secondary support roles, based upon on-the-job exposure, training, and data deposit-related responsibilities [4]. The University Libraries developed three teams, which combined would constitute the KiltHub Repository Team. These three teams were classified as the Repository Services Team, the Data Services Team, and the Liaison Librarian Team.

6.1. Repository Service Team

As Lee and Stvilia present in their 2017 study on practices of research data curation in IRs, in many cases the repository staff are the first to interact with users, and can coordinate the next steps in the workflow, and any additional service provides who may be involved in the data deposit [49]. The Repository Services Team is the first to interact with deposits, and coordinate the stages of the curation workflow with any future involvement of the additional repository teams. The Repository Service Team is comprised of three individuals: The Scholarly Communications and Research Curation Consultant, the Repository Specialist, and the Data Deposit Coordinator. The Scholarly Communications and Research Curation Consultant is the faculty librarian who is overall responsible for the repository and its related services. They are responsible for the communication and interactions within the repository team, and serves as a liaison between the university and the vendor. They also oversee the overall mission and future goals for the repository.

The Repository Specialist is a 1 FTE University Libraries staff member, and serves as the primary repository manager. They serve as the day-to-day lead of the repository and site-level administration, and oversee deposits and questions from users. They also liaise with the University Libraries cataloging unit to oversee the submission of Electronic Thesis and Dissertations to KiltHub and to other ETD services, such as ProQuest. The Data Deposit Coordinator is a full FTE staff member with the University Libraries, but is only a 0.15 FTE with KiltHub. They are responsible for overseeing data deposit submissions to the repository. They ensure the data deposit is compliant with the requirements for general data deposit, as well as ensuring the submission is compliant with the data deposit requirements. The Data Deposit Coordinator has received additional training and development specifically related to best practices and standards for the deposit and dissemination of research data. In this model, the organizational makeup and composition of the Repository Services Team is comparable to the core service teams seen at other institutions, such as the Illinois Data Bank at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and Deep Blue Data from the University of Michigan [40].

6.2. The Data Services Team

Academic Libraries have become an important stakeholder and builder of the culture and infrastructure for research data services [4]. In their 2013 final report, the DMCI at the University of Minnesota found that a successful and significant repository service would be built around capacities for data management and curation to coalesce in operational effectives [29]. Because of this, it was important that the faculty and staff within the University Libraries who provide research data services would the second core team to the KiltHub service.

The Data Services Team is comprised of three individuals: The Research Data Management Consultant and the two CLiR Fellows currently serving in their post-doctoral fellowships at CMU in Data Curation in the Sciences and Data Visualization and Curation. The Research Data Management Consultant is the faculty librarian who is overall responsible for research data management services within the University Libraries. They liaise with the Repository Services Team to ensure that the repository is adhering to data best practices for the deposit and dissemination of research data. They also serve as an additional layer of engagement, directing campus community members to utilize the repository for their data deposit needs when required or permitted by a funder or publisher when related to a grant or publication. While members of the Data Services Team, the two CLiR Fellows are not operational members of the data services or workflows. The CLiR program is a two-year post-doctoral program offering recent Ph.D. students an opportunity to develop new tools, resources, and services, while exploring potential career opportunities [50]. Because of their short-term status, the University Libraries did not want to design operation services around postdocs. Additionally, the CLiR Fellows in the CMU cohort at the time of the development of the workflows were involved in data services and software curation, which is why their involvement is of note. This may not be the case with future potential CLiR Fellows, which further reiterates their supporting roles to the Research Data Management Consultant. The CliR Fellows supply additional support for the Research Data Management Consultant by providing additional outreach and overview support for data deposit, especially when reviewing unique content, such as software and code. The CLiR fellows have also assisted in reviewing interactions between the three teams within the University Libraries, as well as between the University Libraries and campus constituents, and have aided in the development of additional outreach and engagement resources specifically geared towards improving the stream of information for reviewing data deposits. The Data Services team provides a secondary layer of support to the Data Deposit Coordinator during the review of data to ensure that data deposit best practices are being exercised.

6.3. Liaison Librarian Team

Given their close relationship to both the discipline and their faculty, subject/liaison librarians have been found in many studies to be key stakeholders in research data management and the foundation for repository services that require high levels of collaboration [29,51]. The third team with the University Libraries that supports the repository is the Liaison Librarian Team. The liaison librarians are the faculty librarians that serve as liaisons and subject specialists to the schools, departments, research centers, and institutes around the university. In most cases, a liaison serves in a direct 1:1 relationship to a particular campus unit, but in other cases, they are responsible for multiple units and programs. The liaison serves as a bridge between the University Libraries and the rest of campus. They provide marketing and engagement of University Libraries’ tools and services to university constituents. They also provide recommendations to utilize KiltHub as a repository solution for research data and other scholarly outputs as appropriate and permissible by requirements of a funder or publisher. In recent times, the University Libraries has expanded its liaison corps, through filling vacant positions with new hires, as well creating new positions to fill needed and necessary roles. Many of these new hires have included information professionals that hold PhD’s within the disciplines they liaise to, and are able to discuss the outputs of those communities more directly with their constituents through their shared backgrounds and experiences.

The liaison team serves as another level of support to the Data Services Team and the Data Deposit Coordinator if there are any questions on how the data submitted may have been collected, described, and arranged. The liaisons also provided information and background over any disciplinary best practices that should also be accounted for when depositing unique forms of data. In a few cases, when a liaison is interested in serving as a repository administrator for their liaising units, these liaisons take over the administrative roles for deposits normally overseen by the Repository Specialist and the Data Deposit Coordinator. While the liaison may request to take on these roles, the Repository Specialist and Data Deposit Coordinator still provide overall oversight around the work being done by the liaison administrators. The liaison administrator role is an optional responsibility, but more liaisons are taking on this role as a means to further engage with their constituents, and to stay abreast on their current research.

7. Streamlining Workflows

With so many invested interests within the repository, it was critical to understand the potential roles that were required within a streamlined repository deposit workflow. Beyond understanding the roles of the various parties, developing a coherent workflow also highlighted the services and expertise offered during the various stages in the workflow. In this way, the workflows are not just a set of tasks to be reviewed and completed, but they are also a suite of services tailored to address key components of the data life cycle [29]. Beyond ensuring that the deposit is satisfactory completed, the workflow also ensures that librarians and library staff have the opportunity to address any concerns with the deposit, and also ensure that the deposit itself follows best practices. During the various stages of the workflow, those assigned to those tasks can ensure that the deposit is adhering to certain standards, such as the FAIR guiding principles, which will ensure that the deposit is prepared and maintained in a way that makes the dataset findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable [52].

7.1. Workflow Roles

The workflow serves as a means to curate, document, review the deposit, thus ensuring and enhancing the value of the deposit and the final published work [42]. The workflow is intended to act as a means to review the materials and information submitted by the user. Since the creation of the deposit, the KiltHub repository teams have yet had a deposit that met the full set of requirements for deposit, and thus not needing any review or enhancements provided by the three KiltHub repository teams. When assessing the necessary roles required to maintain the streamlined workflows, the University Libraries assessed team member involvement based upon a minimum involvement model that focused on particular roles within the workflow.

Additionally, the workflow was reviewed for adaptiveness for the inclusion of additional team members when and if necessary. The workflow is intended to create a process of review that ensures the deposit meets the minimum set of requirements. The assessment of the workflow was based first on an initial evaluation of work and involvement, but evolved to its current model after assessment of early deposit use case examples. As noted by Michael Witt, no workflow is without review or revision, as workflows themselves are designed in iteration [3]. The deposit workflow has several distinct roles. These roles are activated depending on the type of material being deposited. For example, for a dataset deposit, KiltHub has five distinct roles. In the data deposit workflow, the Repository Administrator, Data Deposit Administrator, Data Services Team, Liaison Librarians, and the Research Data Management Consultant will all have a potential role to play in the deposit.

All user-submitted workflows begin in the same manner. Once a user has added the appropriate required and optional metadata and uploaded their data files and the required README.txt file, the user will then click submit. The metadata that comprises the submission metadata record can be broken down into required and optional metadata [53]. Both sets of metadata are built using qualified and unqualified Dublin Core. The required metadata includes the deposit’s title, author listing, categories taxonomy, file type, keywords, description/abstract, and appropriate copyright license. The categories taxonomy is based upon the Australian and New Zealand Standard Research Classification (ANZSRC) [54]. The repository possesses a wide range of available copyright licenses, included the full suite of Creative Commons licenses, GPL, MIT, and Apache licenses [53]. KiltHub also permits users to select “In Copyright” for items that cannot be deposited utilizing an open license. When this option is selected, users must enter the copyright statement in the Publisher Statement field, which is a requirement for deposit if the “In Copyright” license is utilized. The optional metadata that can be supplied by user includes related funding information (grant name and number/ID), references to related content, and date. Data is not required by KiltHub because the repository will assume the date the items are published to the repository will be the official date of the items if no information is provided in the date field.

Once the user clicks submit, they are informed that their dataset submission will be reviewed by the site-level administrators. The site-level administrators are either the Repository Service Team or the liaison librarian that has taken on the job of repository administrator for their school or department. Once the user clicks ’publish’, a deposit notification is sent by the system to all site-level administrators, including the Repository Specialist. Unless administrative review has been assigned to another individual, such as the site’s liaison librarian, the Repository Specialist is the reviewer for that site. The Repository Specialist begins by conducting an initial review of the content from the notification. Their responsibilities include reviewing the submission metadata that accompanies the deposit and verifying the files attached with the deposit.

The data deposit workflow is initiated once a submission is made in the repository by a user that has been marked with the content-type ’dataset’ within the Figshare for Institutions content-type metadata field. This metadata field is a required default metadata field for all deposits made to Figshare for Institutions repositories. At CMU, the University Libraries made the decision that all datasets, regardless of file types, would be marked as ’dataset’, rather than utilizing other content types that were more representative of the types of file extensions that one may associate with other content types (e.g., using ’filesets’ for tabular data/spreadsheets). If the submission is identified as a dataset, the Repository Specialist assigns the deposit to be reviewed further by the Data Deposit Coordinator. This will trigger a notification to be sent to the Data Deposit Coordinator to begin the data deposit workflow.

7.2. Data Deposit Workflow

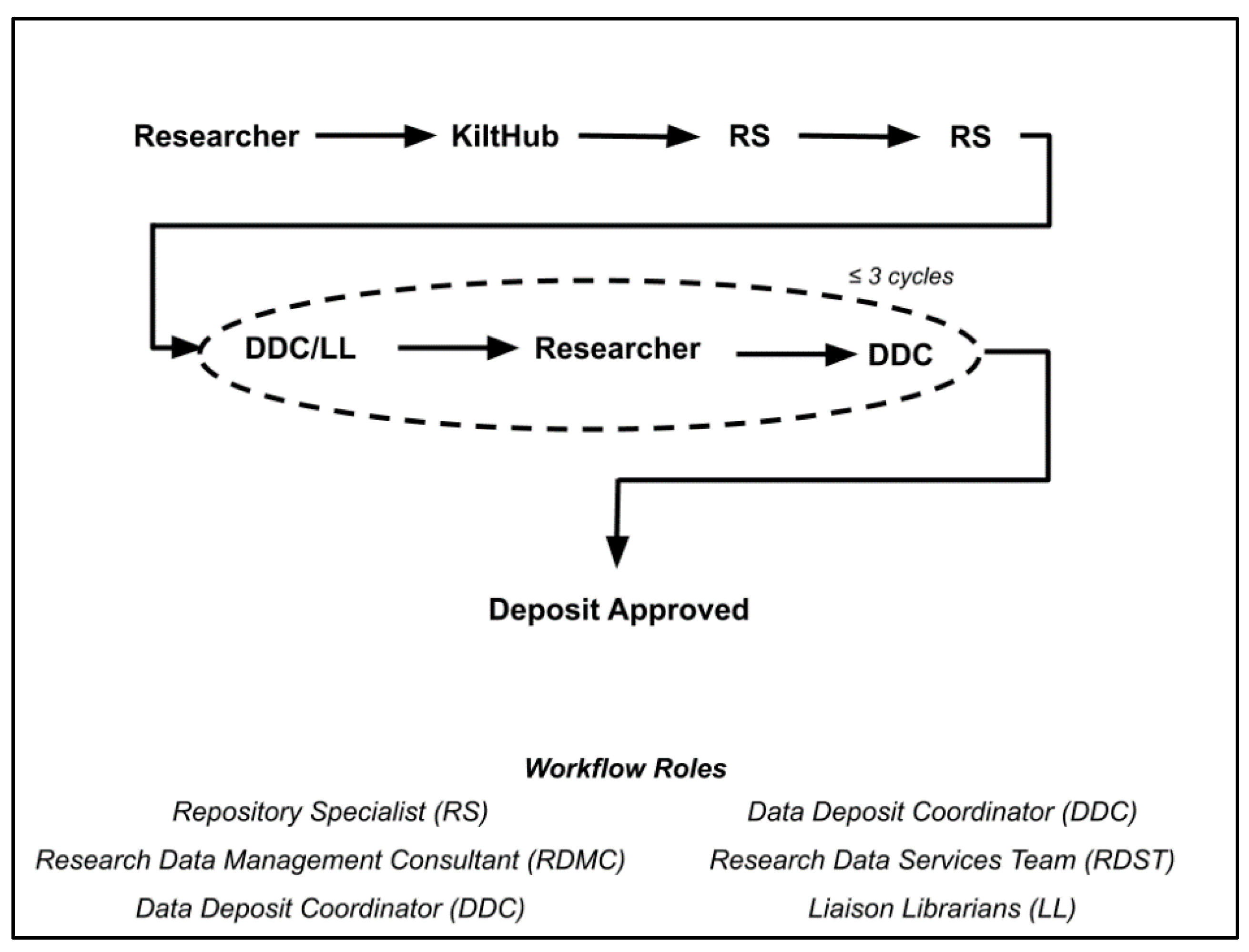

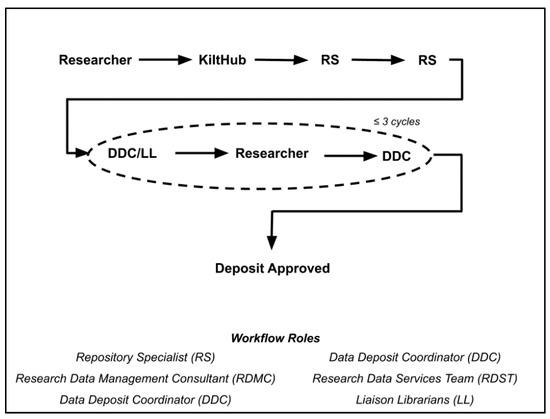

The data deposit workflow begins as soon as the Data Deposit Coordinator is assigned to the dataset. From this point forward, the deposit workflow is best described as an “intricate dance of communication, verification, and iteration” [29]. As illustrated in Figure 1, once assigned to the dataset, the Data Deposit Coordinator begins by reviewing the deposit metadata for deposit requirement consistency. This is to ensure that all of the required metadata that must accompany a data deposit to KiltHub has been provided. Once the deposit metadata is checked and verified, the Data Deposit Coordinator reviews the dataset files and the README.txt file. The README.txt file is a text file that must accompany all dataset deposits. The file includes additional metadata about the dataset, and verifies the contents for data deposit consistency.

Figure 1.

The KiltHub Repository Workflow. The steps in bold represent the minimally required steps within the workflow.

If the dataset meets all the deposit requirements, the Data Deposit Coordinator will approve the dataset for deposit. By approving the dataset, the system will send an automatic notification to the researcher that their dataset has been published in KiltHub. This will also complete the registration process for the datasets DOI with the DOI registering authority, and can then be used for citation and discovery purposes. If the dataset does not meet all deposit requirements, the Data Deposit Coordinator will email the researcher to make initial contact. In their message, the Data Deposit Coordinator informs the researcher that they are reviewing their dataset and may be in further contact with questions regarding the deposit. The coordinator will also contact the researcher’s liaison librarian to confer on questions or concerns they wish to raise and review.

With input from the liaison librarian, and if additional information or expertise is required, the Data Deposit Coordinator will contact the Research Data Management Consultant to involve the Data Services Team in the review of the dataset. After conferring with the Data Services Team and Liaison Librarian, the researcher is contacted again. The initiator for the contact is based upon the liaison’s preference, and will be conducted by either the Data Deposit Coordinator or the Liaison Librarian. The email sent to the researcher will summarize what revisions or additions are necessary for the dataset to be approved for deposit. All parties involved in the workflow to this point are cc’d in the email to the researcher. This is to maintain the flow of information between all team members involved in the deposit. This team-based approach to the data deposit workflow relies heavily upon the communication between the team members and the author of the dataset [49]. Because so many are involved, no one person is left to provide all that is necessary for the deposit. As skill sets amongst members may differ, relying upon the expertise of the collective service providers is essential in delivering a cohesive repository-based data management service.

Based on the circumstances of what is needed to be revised or added, the work is completed by either the researcher or the Data Deposit Coordinator. If the decision is to allow the coordinator to conduct the work, they will utilize their repository-level administrative privileges to access the researchers account and make the changes. If the decision is for the researcher to conduct the work, the dataset will be rejected. This is so that the dataset can be released from the review process and returned to the researcher for revision. An internal comment is left attached to the deposit detailing to the researcher what work is required. This note will accompany the rejection notice in the form of an email to the researcher.

Once the researcher receives the rejection notice, they can begin to make the changes to their dataset detailed in the rejection comments. After the researcher makes the requested changes to the dataset, they can resubmit the dataset for a second review. In the second review, the dataset is reevaluated, ensuring that all of the necessary changes were indeed made by the researcher. This last stage of the workflow is considered iterative, as the researcher may not have made all changes requested when they resubmitted the dataset to be reevaluated. As figure one details, this last stage is repeated as necessary, but only for a certain number of iterations. The KiltHub Repository Team has determined that as long as the minimum set of requirements for deposit have been made, this last iterative stage of ensuring a complete and “perfect” deposit are met will be cycled for a maximum of three iterations. As long as the minimum requirements are met, the dataset will be accepted for deposit by the Research Data Deposit Coordinator after the third iteration, even if not all detailed revisions were made by the researcher.

Similar to the findings of the University of Minnesota implementation report, the University Libraries repository service model focuses on four primary service model outcomes: self-deposit, curated workflows, policy-driven decision-making, and “freemium” services where costs can be written into grants when necessary [29]. While the service does have a means to provide cost recovery capabilities, the core repository offering is taken by the university libraries as the initial burden of service of the institution.

Since the creation of the current deposit workflow and the increased involvement of the service providing team members with the University Libraries, the repository has seen an increase in deposits. Likewise, consultations for data deposits have also increased. Consultations have taken place in-person during scheduled meetings, weekly repository office hours, as well as digitally through the shared repository and data services email accounts that connect the entire service teams to one another. Additionally, communication gathered during these consultations are shared and disseminated through synchronous communication provided by a shared Slack service, as well as during biweekly meetings held with the research data services units.

8. Balancing Requirements with Ease of Deposit

The decision to limit the number of iterations within the number of times the repository team must communicate with the researcher; establishing a minimum level of requirement for deposit was in recognition that the repository needed to balance the requirements for deposit against the ease of use and deposit to the repository. Part of this balance was to ensure that there was a clear and articulated set of minimum requirements for deposit, since the materials within the repository would be considered curated content versus freely available [3]. The minimum requirements for a deposit include the submission metadata, the README.txt file, and a proper file naming convention applied to the dataset files. The requirement of accompanying files, such as the README.txt file, is not unique to CMU’s deposit workflow. In Don Joon Lee and Besiki Stvilla’s 2017 survey on research data curation in institutional repositories, several responding institutions indicated that they also required such additional files, with many including additional domain-specific and data collection specific metadata not found within the item’s primary Dublin Core-based descriptive metadata record [49].

The last requirement is the usage of appropriate file types for access and preservation. This may still include proprietary file types, depending on the data, but open file formats are recommended whenever possible. The requirements are kept to a minimum so that researchers do not feel as if the repository or the University Libraries are asking for more information or a higher level of completeness than what is expected to be supplied within a disciplinary setting.

Likewise, the deposit process and services have to provide a smooth and easy to understand process for users to utilize that will also highlight the benefits of deposit. Some of these processes include a quick and easy submission process, responsive communication turnaround times; providing mechanisms, such as DOI generation and holding, for a deposit. The DOI is available for generation and holding before the dataset is published, allowing researchers to embed the DOI citation for their work in publications and funder documents while the materials are being developed. Additionally, the depositing and publishing of the dataset ensures that the deposit can comply with requirements from publishers and funders.

The second layer of concern KiltHub is presented with is because it is built on a system that users may be accustomed to already using. Since Figshare for Institutions is based upon figshare.com, users will recognize these preexisting requirements and processes. The requirements or steps to ease deposit that were implemented at CMU could not be seen as being higher, more strenuous, or extensively different than the same expectations within figshare.com. If KiltHub had stricter requirements, or provided fewer offerings to ease deposit, it could negatively turn the CMU community towards using figshare.com over its own campus-based solution. For example, one of the main differences is the minimum amount of information necessary for deposit in KiltHub is greater than that of figshare.com. This increased amount of information necessary for deposit increases the amount of time necessary to complete a deposit, which Austen et al. noted, is seen as a major disincentive for sharing data via repositories [42].

While the Figshare for Institutions vs. figshare.com comparison was a concern for CMU, the concern of having a campus solution seen as stricter or harder to use over a freely available or alternative solutions should be a concern for any institution offering these types of services. Ultimately, the repository service cannot overburden the research with too many requirements or implement a deposit workflow or submission process that would be viewed as overly complicated. Without taking these points into account, ensuring these requirements are kept to what is essential, and developing a repository service focused on ease of use, the IR service will either not be used over an alternative service; or worse, the University Libraries could be accused of not thinking of the best interests of their campus community.

9. Institutional Repositories and Repositories at Institutions

Balancing the deposit requirements for the new comprehensive repository, and the services offered as a benefit of the repository or to ease deposit, centered on the notion of what it meant for KiltHub to be an Institutional Repository (IR) versus a repository at an institution. When considering what it means for a repository to be an IR, there are several questions that one can ask. The first question is what does it mean to be defined as an IR? Does it mean the repository will hold textual materials and not data? Or will the repository contain academic and research outputs, but not other materials that may have been housed in other types of repositories? Related to these previous questions, what will be the role of the IR? How will its role affect its limitations and capabilities? If the IR can accommodate the needs of the content and its users, why should it be limited in role or responsibility? This ultimately questions the types of material it can collect from both a technical and contextual perspective. Should the repository collect content that it cannot accommodate, or provide users a means to use or preview? Lastly, since we have seen that IRs, both in their technical and contextual capabilities, is it time to reevaluate how we define an IR’s mission as well? Can an IR serve a larger role than just as a home for outputs of a particular institution? By examining the repository beyond its own confines, can the IR serve a larger role? The University Libraries addressed these questions during its evaluation, selection, and implementation of KiltHub and its related services. In the future, as KiltHub and its service matures, the University Libraries will continue asking these questions to ensure that its approach to each question is in alignment with its mission, capabilities, and focus in providing such tools and services.

The other perspective within this conversation is in regards to general repositories maintained at an institution. If the repository is truly “institutional,” how should it be administered? What level of control or administration does an institution need over its repositories? Does this level of control and oversight alter how one decides to administer the repository? How should an institution provide a repository as a service? If the repository is institutional service, how does it fit within the broader system of services and mechanisms offered by the institution? Can a repository be a part of the broader scholarly communication ecosystem at an institution? If a repository is a part of the broader scholarly communication ecosystem, what type of role can it potentially play? Especially when considering how researcher’s outputs may transition amongst the various stages of the research lifecycle. Repositories at an institution are more than just the software they are built upon. The entire repository is comprised of several components, which may include its technical infrastructure, policies, staff, and partnership [29]. All of these components are what make repositories at institutions a comprehensive repository solution.

11. The IR and Current Research Information System

Like any other technical space, there has now become a plethora of RIM solutions available. While RIMs are traditionally viewed as a service focused towards academic leadership within faculty affairs or the research office. With that being said, many institutions see benefits in having the implementation and overall oversight of these systems provided by university libraries. In the Choice white paper, “The Evolving Institutional Repository Landscape,” Judy Luther identifies many of the new and emerging roles associated with repositories. These roles include their relationship to new emerging systems being adopted in academic institutions today, including RIMs [57]. Additionally, John Novak and Annette Day, present that the new administrative role of working with RIMs, presents repositories with another new dialectic [44]. In this model, CMU is no different, and has begun to align this new face for its repository by integrating it to the CMU RIM system—Symplectic Elements.

Because RIMs are designed to gather information on faculty activities and outputs, they have a similar mission to IRs, and since these systems share these parallel goals, many RIM systems have developed integrations of various sorts to connect in some sort of means to an institution’s IR. While the placement of RIMs may differ, it is important that librarians understand the role they potentially have with interacting with these systems. Additionally, because these systems are designed to ingest a wide range of information about a faculty member, including their publications and research activities, librarians are poised to provide a level of expertise and professional knowledge on how to best optimize how this information is gathered and verified. Likewise, the repository has an opportunity to provide useful information on materials not found within other sources synced to the RIM, such as gray literature, software, and research data. The CMU University Libraries recognized these opportunities through the implementation of KiltHub and Symplectic Elements. Through the interoperable capabilities of these two systems, there could be mutually beneficial outcomes that would ultimately improve the mission and functional capabilities of each system.

11.1. IR to RIM

As the RIM harvests publication information from multiple sources, the repository can also be integrated to serve as an additional publication source. Through crosswalks established between KiltHub and Elements, the metadata records of content published in the repository are matched to the corresponding publication record found within Elements. Additionally, both systems utilize the same user feed to create and maintain user accounts. This is based upon the usage of the CMU personnel identifier (Andrew ID) and CMU email address (AndrewID@andrew.cmu.edu). By matching this information from KiltHub to the information located within Elements, the faculty member’s publication records are further validated. Because both systems use the common author profile information, this matching between records in KiltHub does not require authors to claim the publication within Elements or KiltHub. The new record found within KiltHub is connected to the additional records found from other sources, thereby allowing a faculty member to review the location where Elements found the information from each source.

Additionally, the repository is used as a harvesting source for publications and other materials not found within Elements. This matching and connection is made through the usage of the DOIs published by KiltHub and the DOIs found within the metadata of items found in the Elements content indexing searches. These materials are found by the Elements indexing searches through name identification, as well as through using other known author identifiers found within the data sources, such as ORCID, Scopus ID, and Researcher ID [58]. When an item found within KiltHub is not matched to an existing record within Elements, the system will generate a new record for that item within Elements. This record sits within the faculty member’s full listing of publications, and identifies the record as originating from the KiltHub repository. Further work is being done to improve this connection and content identification. Because KiltHub creates a DOI for all published records, this causes items added to KiltHub through Green Open Access to have two DOIs. One DOI is the publisher DOI to the version of record, and the second DOI represents the deposit in KiltHub (i.e., the repository DOI). Additional work between CMU, Figshare, and Symplectic is currently in progress ensuring that Elements can understand the nuances of these two DOIs and the connection they have to one another if both are present on a single record. This additional work will ensure that Elements will not add the KiltHub record for publications as a new record, but will know that the record found in KiltHub’s is the record of a publication it may have already indexed.

11.2. RIM to IR

Because the RIM is a hub for publication information—information that it has been able to search, query, and collect through automated processes—these same processes can be extended to provide a mechanism to gather content that may be suitable and permissible for deposit to KiltHub. Because the data has been gathered through machine-readable processes, the metadata can be reviewed through additional tools to review if the publisher permits repository deposit by comparing the source information found within SHERPA/RoMEO [59]. Within Elements, the Repository Tools module allows for publication data to be checked for deposit. When a publication is claimed by an author, it can then enter the repository review process. In this process, a publication’s source will be reviewed through the connections between Elements and SHERPA/RoMEO. If a publisher allows for the deposit to a repository, Elements will indicate this information to the user, and provide them the opportunity to attach the appropriate version of the article permitted by the publisher. Once the user supplies the appropriate file, they can also agree to the terms of the repository’s deposit agreement. Once the user agrees to the terms and clicks submit, the metadata record from within Elements is supplied as the repository submission record along with the publication files. The submission metadata and deposit files are supplied to the repository to be reviewed by the Repository Specialist.

This process allows for the full metadata record that was used to populate the Elements publication record to be utilized to complete the repository submission. Because the deposit still enters the traditional repository review workflow, the content is still curated and verified by the Repository Specialist. Since these two systems use the same user feed and account verification mechanisms, the systems can again ensure that the publication will be associated with the correct authors once the deposit is completed. This feature currently provides deposit for publications, but CMU is working with Symplectic and Figshare to see how this functionality could be extended to other content types, such as research data. Once available, this extension of the publication deposit process will allow users to deposit their content to the repository, regardless of the system they choose to interact with during their primary interaction.

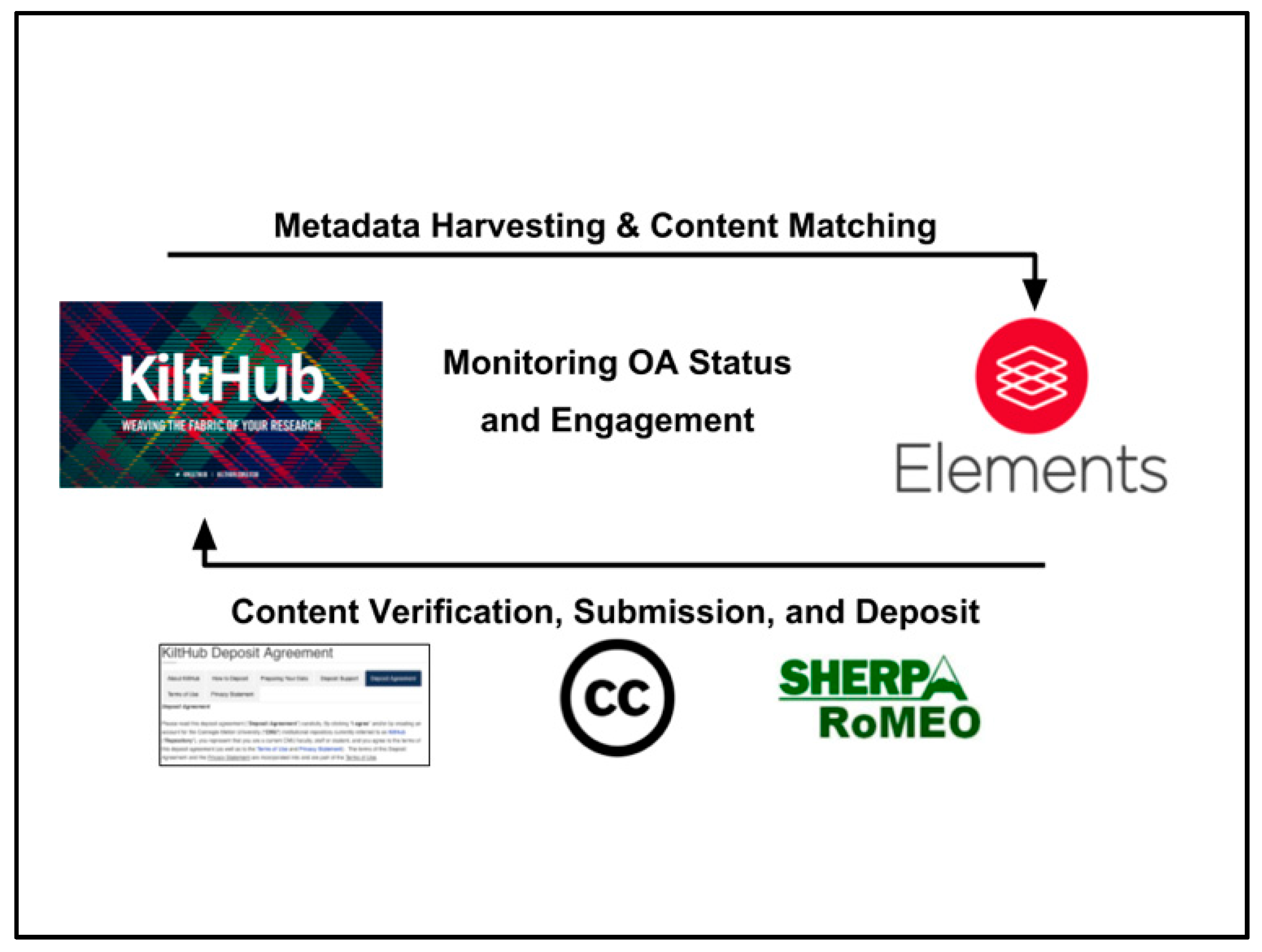

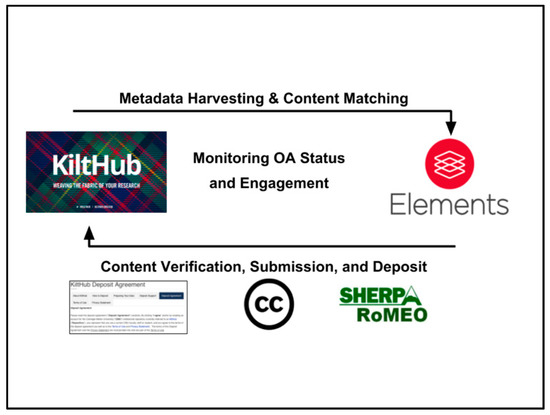

11.3. IR and RIM Ecosystem

As Figure 2 illustrates, by having the repository and RIM interconnected through a two-way integration, both systems are able to combine their primary purposes towards a new shared service model of monitoring the levels of open access. As Anna Clements noted in her article, “Research information meets research data management … in the library?”, we can change the perception of these platforms from just as systems and start thinking of them as more than a system, but as interrelated services [60]. Additionally, Austen et al. found that these integrated workflows resulted in the scholarly objects found in these two systems to be connected, linked, citable, and persistent to allow researchers to navigate smoothly within these systems, thus enabling their reusability for further uses [42]. Whether it was mandated by a funder or not, the open status of any individual faculty member, campus unit, or the overall university could be analyzed and potentially extended when permitted. Additionally, while CMU neither has an open access mandate or any extenuating government requirements to validate that it has complied with open access requirements, the university’s open access status could still be reviewed and enhanced through this dual connection. By using the RIM to monitor open access, the Repository Services Team can utilize the RIM as an additional layer of engagement. Just as the Repository Specialist would review a faculty members CV or faculty website, the faculty member’s Elements profile would verify which publications were authored by the faculty member, as well as provide the necessary information from the metadata record that would be linked via SHERPA/RoMEO to confirm the actions taken to make that publication openly available within the repository. By having the IR and RIM connected by a two-way channel that enables both platforms to fulfill a primary and supporting role for one another, the ecosystem created by these two connections allows the systems to become interoperable. This also allows the passage of information and content to be seen as a seamless connection to both users and administrators.

Figure 2.

The Institutional Repository (IR)-Research Information Management (RIM) System Integration at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU).

Full utilization of the connections and potential benefits of the RIM requires the repository staff to be cross-trained on its usage. Additionally, the repository staff need to have a certain level of access to faculty profiles to engage with faculty publication listings. By ensuring the repository services staff are cross-trained and have the right level of access to the RIM, the RIM can be seen as an additional layer of open access services. By examining the RIM as an additional service layer, it can be further positively marketed to faculty as a service that will improve the discovery and verification of their scholarship without creating another layer of undue burden. If librarians and other information professionals can focus on how these services are interconnected, and can improve how they provide their services, they can provide both a level of expertise and knowledge that disciplinary faculty may not have. Likewise, because of their expertise, they can also free faculty from having to be focused on such matters. As Nicholas Joint points out, this allows the disciplinary faculty to focus on their own research, and not be concerned with learning additional systems or understand how conduct self-deposit [61]. This further illustrates the value that the libraries and librarians provide to both the institution and faculty, and how they can develop additional services from preexisting systems being used across their institutions.

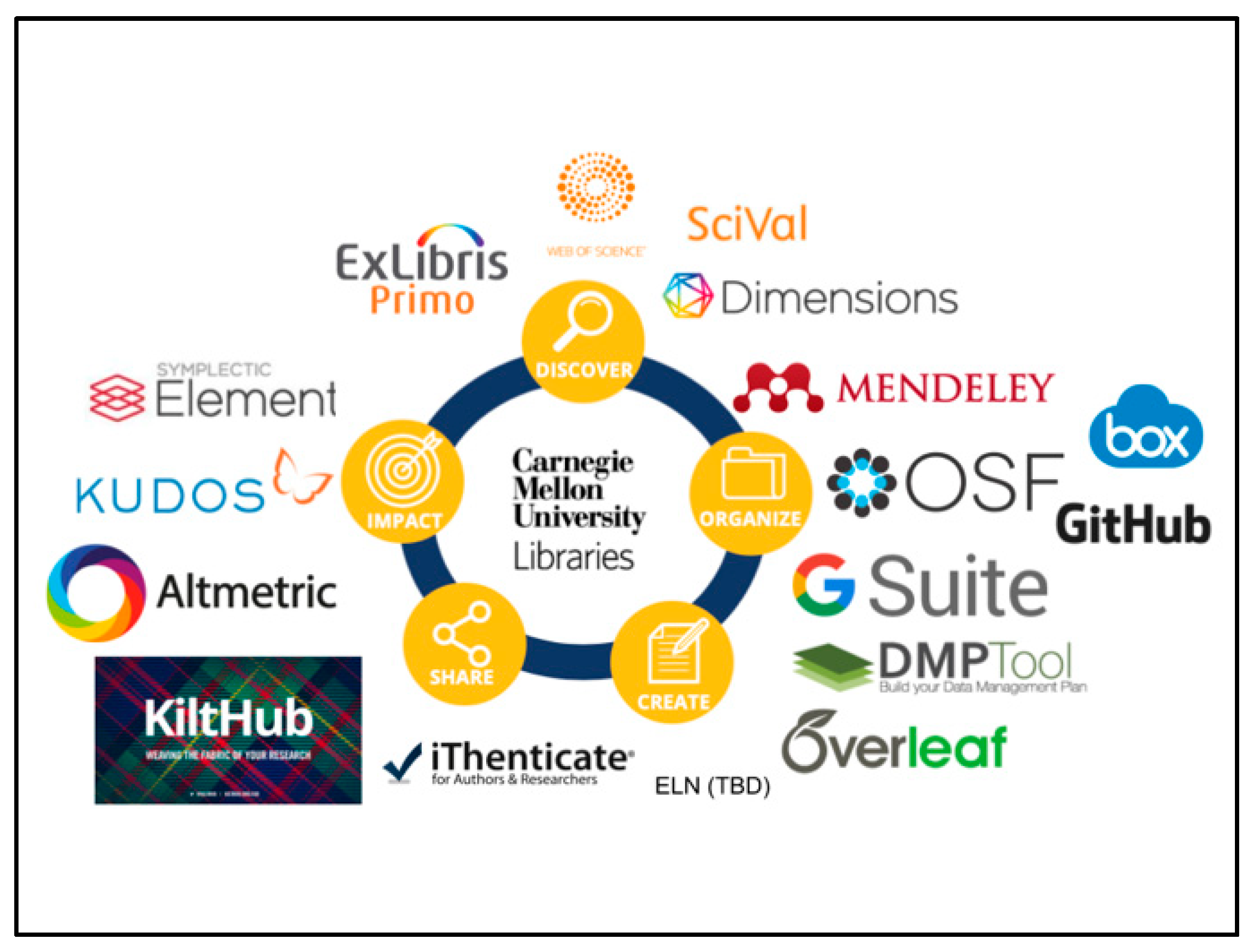

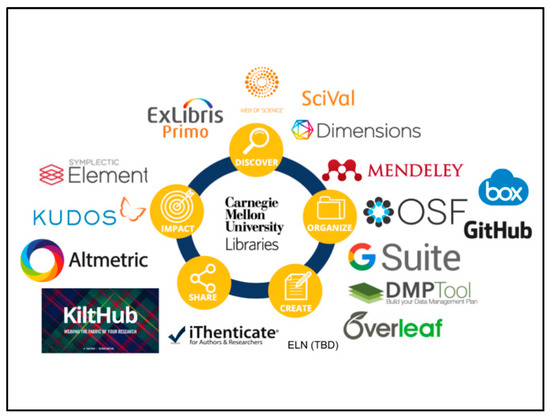

12. The IR in the Scholarly Communication Ecosystem

The role of the repository will continue to change and evolve as the needs of researchers and administrators evolve as well. In this way, the repositories’ dialectic will continue to add additional “faces” [44]. The number of tools and services designed to assist with scholarly communications is increasingly expanding. New tools and services have been created to fill voids where previous support either did not exist, or was inadequately provided. In 2015, Jeroen Bosman and Bianca Kramer presented their findings on their 101 Innovations in Scholarly Communications” at the Force 11 2015 meeting [62]. To date, Bosman and Kramer have identified over 400 different systems, tools, and services [63]. Their work also identified that these innovations could be classified into six different stages (Discovery, Analysis, Writing, Publication, Outreach, and Assessment), which represent a researcher’s workflow. In comparison, the University Libraries has classified its tools and services into a similar model also reflecting the researcher’s workflow. As Figure 3 illustrates, the University Libraries differs from Kramer and Bosman, in that it has identifies only five stages. The five stages represented at CMU are Discover, Organize, Create, Share, and Impact. With these five stages, the University Libraries has classified the services, tools, and platforms that it maintains, supports, or licenses to support the endeavors of its faculty and students throughout the stages of their research and scholarship.

Figure 3.

The scholarly communication ecosystem at CMU.

In creating this ecosystem, the University Libraries has focused on reviewing options within a particular space to ensure that any new additions to the ecosystem are as beneficial to as much of the campus community as possible in a financially sustainable means through requiring interoperability beyond a single vendor’s solutions. A focus of this ecosystem has been to select tools and services that break away from siloing activities and transitions to other stages. Just as an author wants to transition from writing, to publishing, to disseminating, the tools that support these actions should also allow a researcher to transition their outputs from one stage to the next. Whether it is from moving from hosting project files in a cloud-based storage solution, to publishing these materials in the repository, to then measuring the impact of the dissimilation in the form of Altmetrics and traditional citation metrics, researchers want fluidity and ease of movement in their workflows and systems that support their research.

This also means that tools and services should be able to integrate and interoperate with multiple solutions, regardless of their classified stages. For example, a researcher should not be expected to have to move from Create to Share, but can move from Organize to Share to Impact if they do not require Create. By ensuring the greatest amount of fluidity, the researcher can control their workflows without having to create additional workarounds or external solutions. By recommending the usage and creation of the same identifiers used by the repository, the user’s connection to their materials across the ecosystem can be further interconnected, allowing content to be utilized and synced across multiple platforms. Additionally, by having systems that are interoperable agnostic, institutions can feel empowered to review and select the tools, services, and platforms that are the right fit for their institution. Institutions should not feel forced or obligated in selecting services because of big-ticket buy-in or limited integration to systems from the same vendor or service provider.

13. Conclusions—Weaving the Fabric of Research