Grades of Openness: Open and Closed Articles in Norway

Abstract

1. Introduction

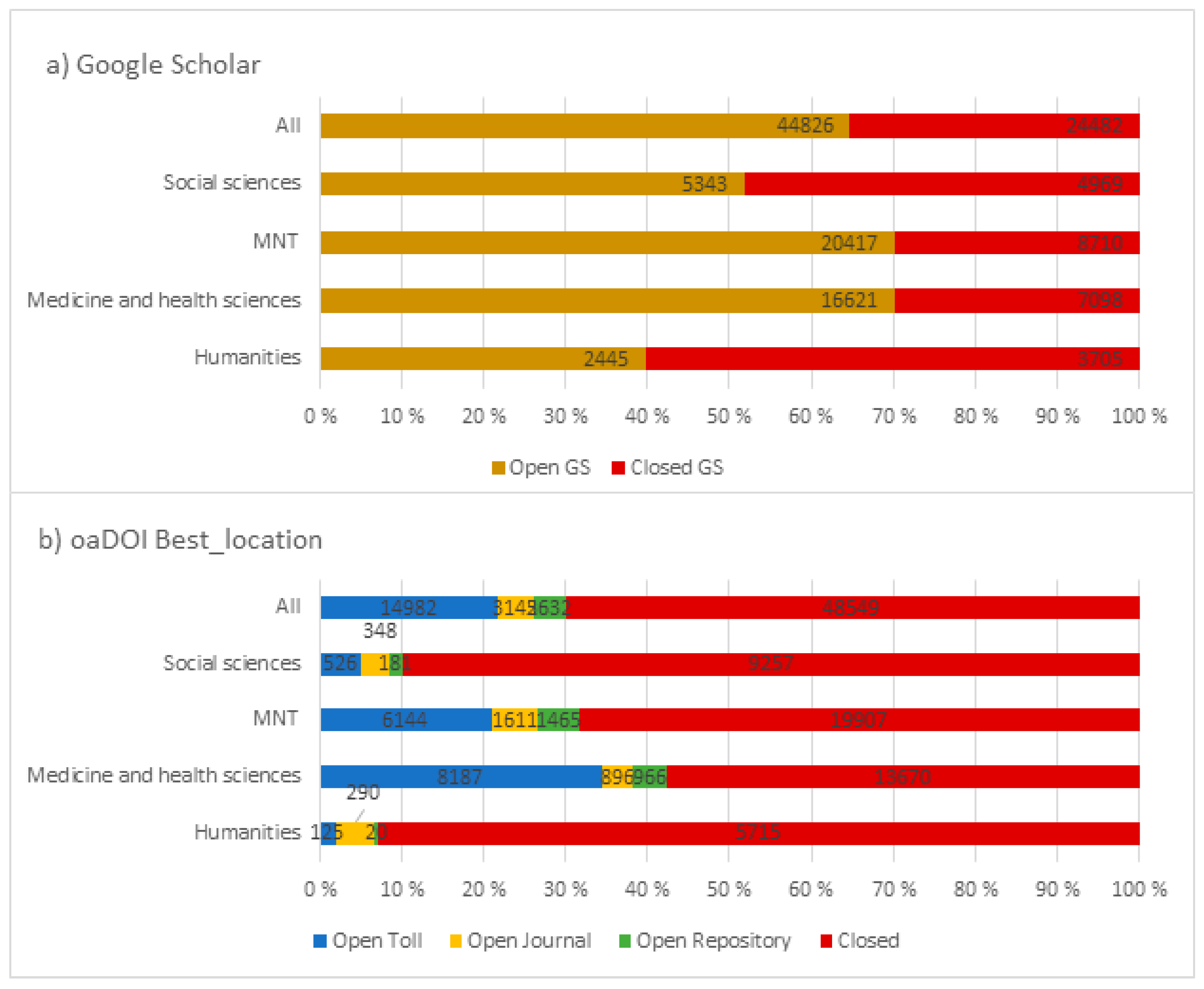

- How large is the share of open availability according to oaDOI?

- What type of open availability is provided?

- How does the citation impact vary by type of open availability?

- How does this share compare to Google Scholar’s free share?

- How does this share compare to 1findr’s free share?

- How open are the different subject fields?

2. Applied Services, Data, and Method

2.1. Applied Services

2.2. Categories of Open Availability

- Open Journal: Typically indexed by the DOAJ, the Directory of Open Access Journals

- Open Repository: Open full-text in approved OA repositories.

- Open Toll: Free via publisher sites, with or without an open license in a toll-access journal.

- Closed: All remaining articles.

2.3. Citations and Subject Fields

3. Results and Discussion

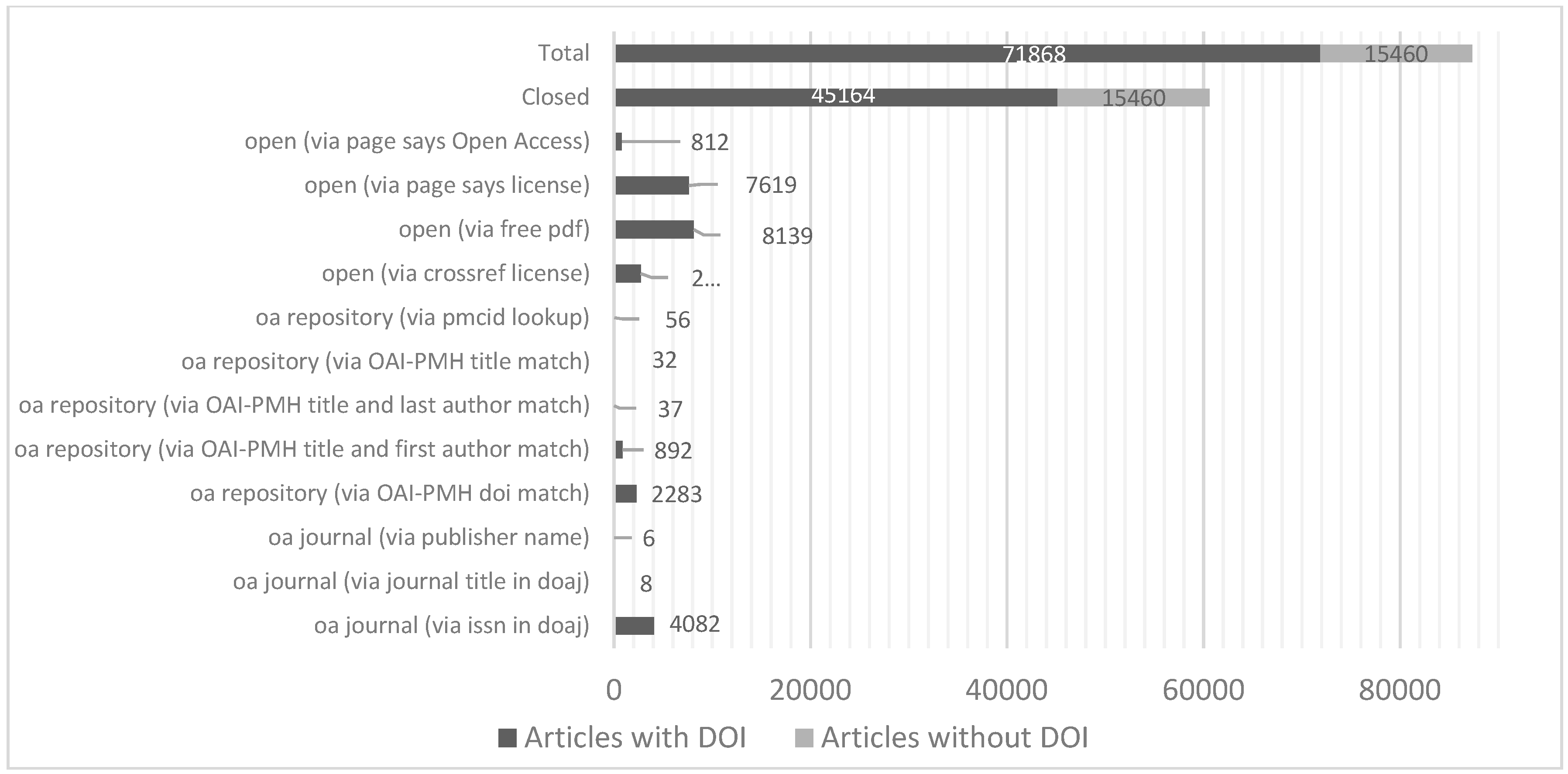

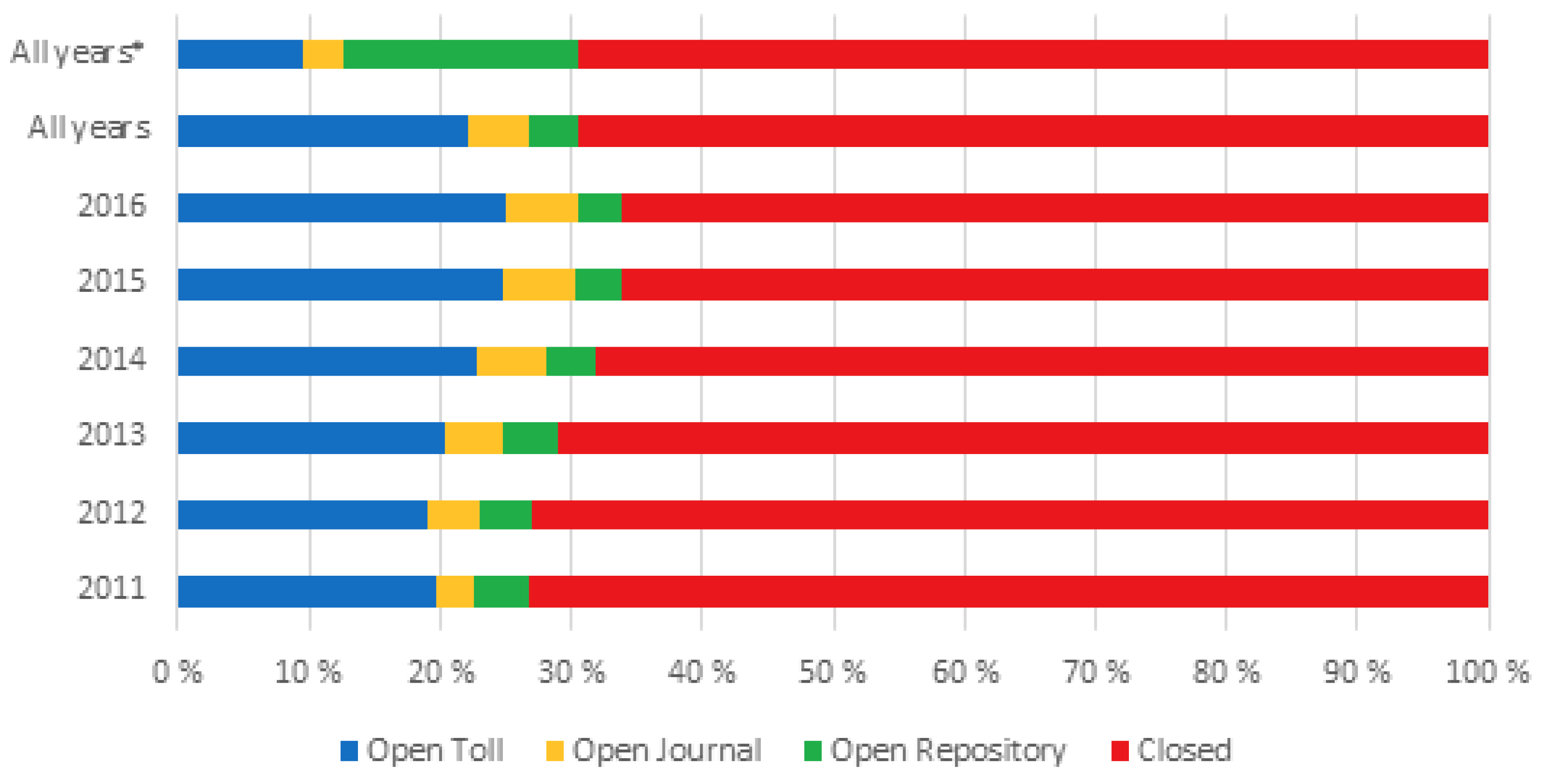

3.1. oaDOI

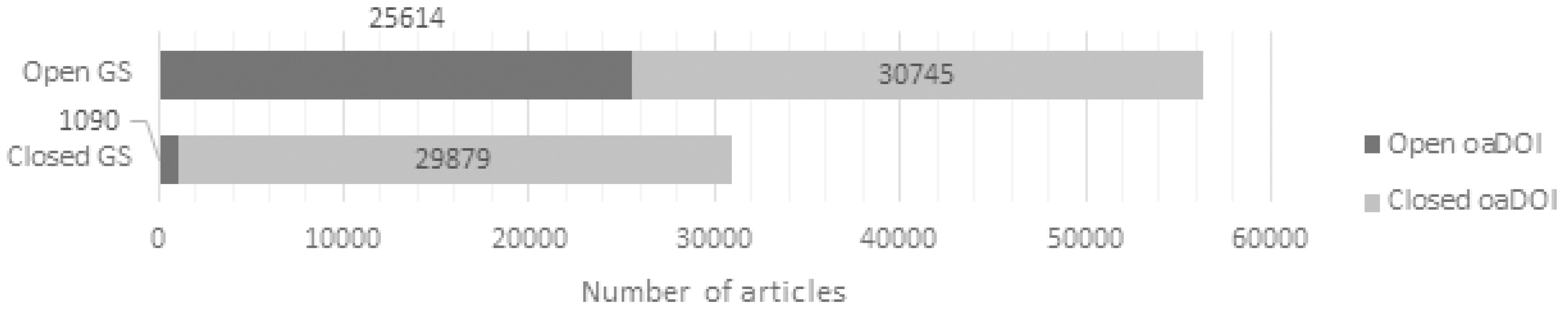

3.2. oaDoi Compared to Google Scholar

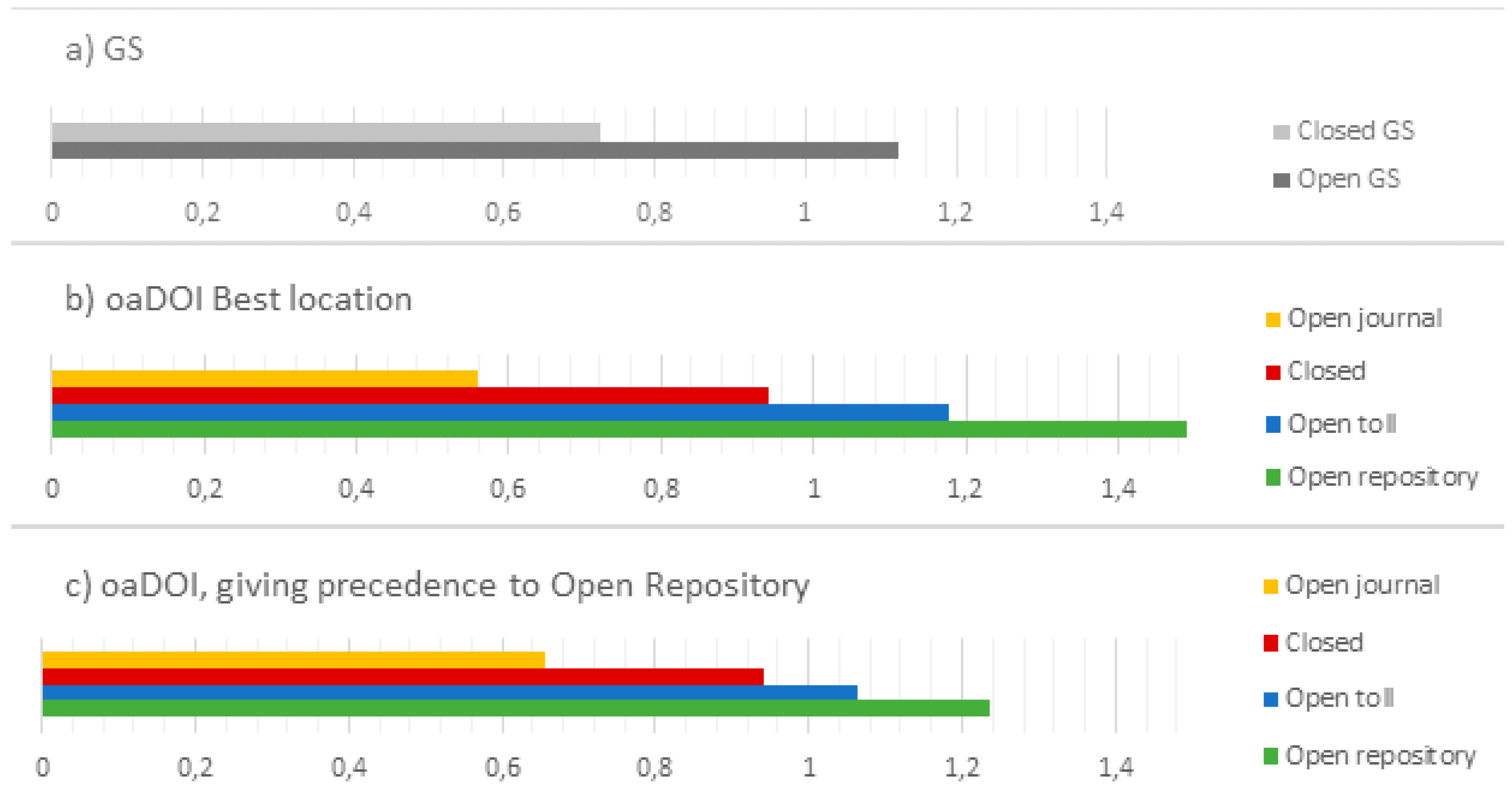

3.3. Citation Frequencies by Type of Openness

3.4. Openness by Subject

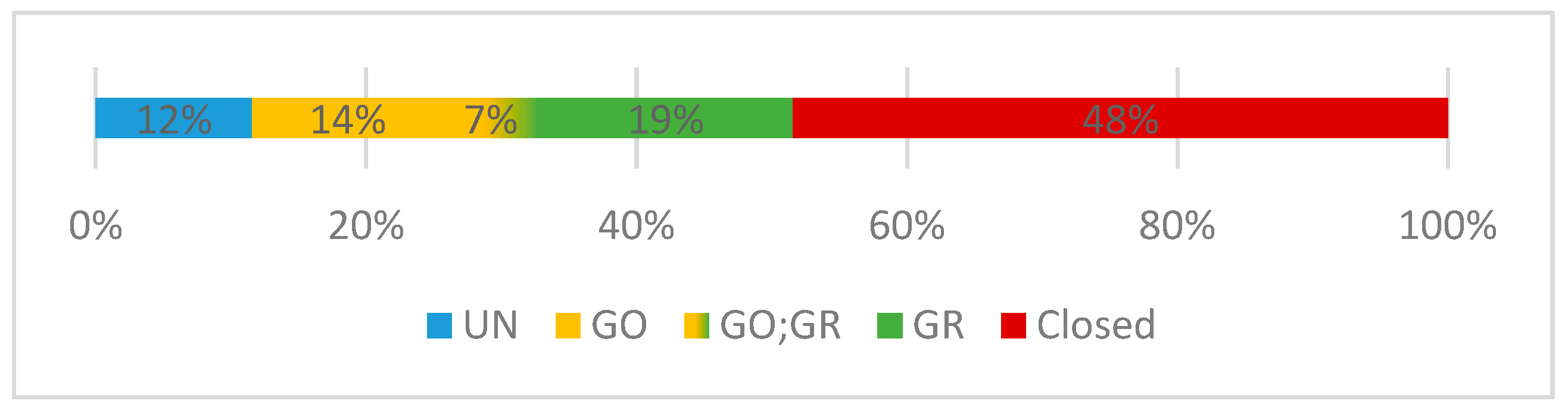

3.5. 1findr

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Education and Research in Norway. National Goals and Guidelines for Open Access to Research Articles. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/national-goals-and-guidelines-for-open-access-to-research-articles/id2567591/ (accessed on 22 July 2017).

- Max Planck Digital Library. Open Access 2020. Available online: https://oa2020.org/ (accessed on 20 August 2018).

- Jamali, H.R. Copyright compliance and infringement in ResearchGate full-text journal articles. Scientometrics 2017, 112, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greshake, B. Looking Into Pandora’s Box: The Content Of Sci-Hub And Its Usage. F1000Research 2017, 6, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archambault, É.; Caruso, J.; Nicol, A. State-of-Art Analysis of OA Strategies to Peer-Review Publications. 2014. Available online: http://www.science-metrix.com/sites/default/files/science-metrix/publications/d_2.1_sm_ec_dg-rtd_oa_policies_in_the_era_update_v05p_0.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2018).

- Martín-Martín, A.; Costas, R.; van Leeuwen, T.; Delgado López-Cózar, E. Evidence of open access of scientific publications in Google Scholar: A large-scale analysis. J. Informetr. 2018, 12, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikki, S. Scholarly publications beyond pay-walls: increased citation advantage for open publishing. Scientometrics 2017, 113, 1529–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar, H.; Priem, J.; Larivière, V.; Alperin, J.P.; Matthias, L.; Norlander, B.; Farley, A.; West, J.; Haustein, S. The state of OA: A large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosman, J.M.; Kramer, B. Open access levels: A quantitative exploration using Web of Science and oaDOI data. PeerJ Preprints 2018, 6, e3520v1. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, L.; Cuplinskas, D.; Eisen, M.; Friend, F.; Genova, Y.; Guédon, J.-C.; Hagemann, M.; Harnad, S.; Johnson, R.; Kupryte, R. Budapest Open Access Initiative. Available online: http://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/read (accessed on 6 April 2018).

- Suber, P. Open Access; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, M.J.; Snyder, C.M. Identifying the effect of Open Access on citations using a panel of scientific journals. Econ. Inq. 2014, 52, 1284–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, E.; Côté, G.; Struck, B.; Voorons, M. Research impact of paywalled versus open access papers. Science-Metrix and 1science 2016. Available online: http://www.1science.com/oanumbr.html (accessed on 7 November 2016).

- Davis, P.M.; Walters, W.H. The impact of free access to the scientific literature: A review of recent research. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2011, 99, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristin. NVI–Reporting Instruction. Available online: https://www.cristin.no/english/resources/reporting-instructions/#toc1 (accessed on 3 October 2018).

- Orduna-Malea, E.; Ayllón, J.M.; Martín-Martín, A.; Delgado López-Cózar, E. Methods for estimating the size of Google Scholar. Scientometrics 2015, 104, 931–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjesdal, Ø.L. Frie-Publikasjoner-Gs. Available online: https://github.com/ubbdst/frie-publikasjoner-gs (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Impactstory. Unpaywall. Available online: https://unpaywall.org/ (accessed on 27 August 2018).

- 1sciene. 1findr. Available online: https://www.1science.com/1findr/ (accessed on 27 August 2018).

- Posada, A.; Chen, G. Preliminary Findings: Rent Seeking by Elsevier. 2017. Available online: http://knowledgegap.org/index.php/sub-projects/rent-seeking-and-financialization-of-the-academic-publishing-industry/preliminary-findings/ (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Det nasjonale Publiseringsutvalget. NPI. Available online: https://npi.nsd.no/fagfeltoversikt (accessed on 13 April 2018).

- Mikki, S.; Zygmuntowska, M. Vitenskapelig publisering ved Universitetet i Bergen: Publiseringsstatistikk 2005–2016; Universitetsbiblioteket i Bergen: Bergen, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Laakso, M.J.S. Green open access policies of scholarly journal publishers: A study of what, when, and where self-archiving is allowed. Scientometrics 2014, 99, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, I.D.; Plume, A.M.; McVeigh, M.E.; Pringle, J.; Amin, M. Do open access articles have greater citation impact?: a critical review of the literature. J. Informetr. 2007, 1, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coalition for Responsible Sharing. Coalition Statement. Available online: http://www.responsiblesharing.org/coalition-statement/ (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- European Research Council. Guidelines on Implementation of Open Access to Scientific Publications and Research Data. (Horizon2020). Version 3.2. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/grants_manual/hi/oa_pilot/h2020-hi-oa-pilot-guide_en.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2017).

| Year | Total Articles | Articles with a DOI | Percentage of Articles with a DOI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 12,821 | 10,102 | 78.8% |

| 2012 | 14,224 | 11,357 | 79.8% |

| 2013 | 13,916 | 11,272 | 81.0% |

| 2014 | 14,574 | 11,885 | 81.5% |

| 2015 | 15,370 | 12,584 | 81.9% |

| 2016 | 16,534 | 14,753 | 89.2% |

| All years | 87,439 | 71,953 | 82.3% |

| Category | Evidence in oaDOI |

|---|---|

| Open Journal | oa journal (via issn in DOAJ) |

| Open Journal | oa journal (via journal title in DOAJ) |

| Open Journal | oa journal (via publisher name) |

| Open Repository | oa repository (via OAI-PMH doi match) |

| Open Repository | oa repository (via OAI-PMH title and first author match) |

| Open Repository | oa repository (via OAI-PMH title and last author match) |

| Open Repository | oa repository (via OAI-PMH title match) |

| Open Repository | oa repository (via pmcid lookup) |

| Open Toll | open (via crossref license) |

| Open Toll | open (via free pdf) |

| Open Toll | open (via page says license) |

| Open Toll | open (via page says Open Access) |

| Closed | All other articles, including those shared only on ASN * |

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| CL | Closed |

| GO | Gold: via DOAJ, hybrid, free to read |

| GR | Green: via repository, including academic social networks |

| UN | Unknown: open versions, may belong to GO or GR |

| Provider | Humanities | Medicine and Health | MNT | Social Sciences | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| researchgate.net | 146 | 2766 | 4181 | 852 | 7945 |

| academia.edu | 284 | 694 | 1091 | 400 | 2469 |

| bibsys.no | 255 | 416 | 611 | 794 | 2076 |

| uio.no | 186 | 79 | 310 | 134 | 709 |

| psu.edu | 20 | 133 | 314 | 104 | 571 |

| diva-portal.org | 20 | 172 | 298 | 74 | 564 |

| acs.org | 26 | 504 | 530 | ||

| hio.no | 58 | 171 | 78 | 172 | 479 |

| arxiv.org | 1 | 2 | 447 | 1 | 451 |

| semanticscholar.org | 12 | 48 | 317 | 46 | 423 |

| uit.no | 104 | 107 | 134 | 72 | 417 |

| infona.pl | 285 | 31 | 6 | 322 | |

| uib.no | 42 | 64 | 153 | 45 | 304 |

| cambridge.org | 46 | 76 | 75 | 47 | 244 |

| ntnu.no | 2 | 5 | 166 | 32 | 205 |

| novus.no | 154 | 38 | 192 | ||

| bmj.com | 189 | 189 | |||

| idunn.no | 33 | 120 | 153 | ||

| tandfonline.com | 8 | 75 | 20 | 18 | 121 |

| Articles | % | |

|---|---|---|

| indexed by 1findr | 70,476 | 81% |

| not-indexed by 1findr | 16,852 | 19% |

| Total | 87,328 | 100% |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mikki, S.; Gjesdal, Ø.L.; Strømme, T.E. Grades of Openness: Open and Closed Articles in Norway. Publications 2018, 6, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6040046

Mikki S, Gjesdal ØL, Strømme TE. Grades of Openness: Open and Closed Articles in Norway. Publications. 2018; 6(4):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6040046

Chicago/Turabian StyleMikki, Susanne, Øyvind L. Gjesdal, and Tormod E. Strømme. 2018. "Grades of Openness: Open and Closed Articles in Norway" Publications 6, no. 4: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6040046

APA StyleMikki, S., Gjesdal, Ø. L., & Strømme, T. E. (2018). Grades of Openness: Open and Closed Articles in Norway. Publications, 6(4), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6040046