A Multidisciplinary Bibliometric Analysis of Differences and Commonalities Between GenAI in Science

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Bibliometric analysis will make it possible to determine the dynamics of the diffusion of selected GenAI tools in science.

- Comparative analysis will help define the disciplinary and geographical specialization profiles of GenAI tools.

- Comparative analysis will enable a segmentation of GenAI tool applications by topical area.

- The resulting findings will allow us to assess the substitutability of GenAI tools.

- Which of the analyzed GenAI tools exhibits the highest growth rate in the number of publications over the years 2023–2025?

- Which of the analyzed GenAI tools exhibits the highest citation-per-publication rate?

- Do the analyzed publication corpora display geographic concentration in the same regions?

- What differences exist in the topical scopes of the analyzed publication corpora?

- What is the scale of the shared keyword corpus across the analyzed publications?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Previous Bibliometric Analyses Based on GenAI

2.2. The Essence of Differences and Commonalities Between GenAI

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection Process

3.2. Data Preparation and Analysis

4. Results

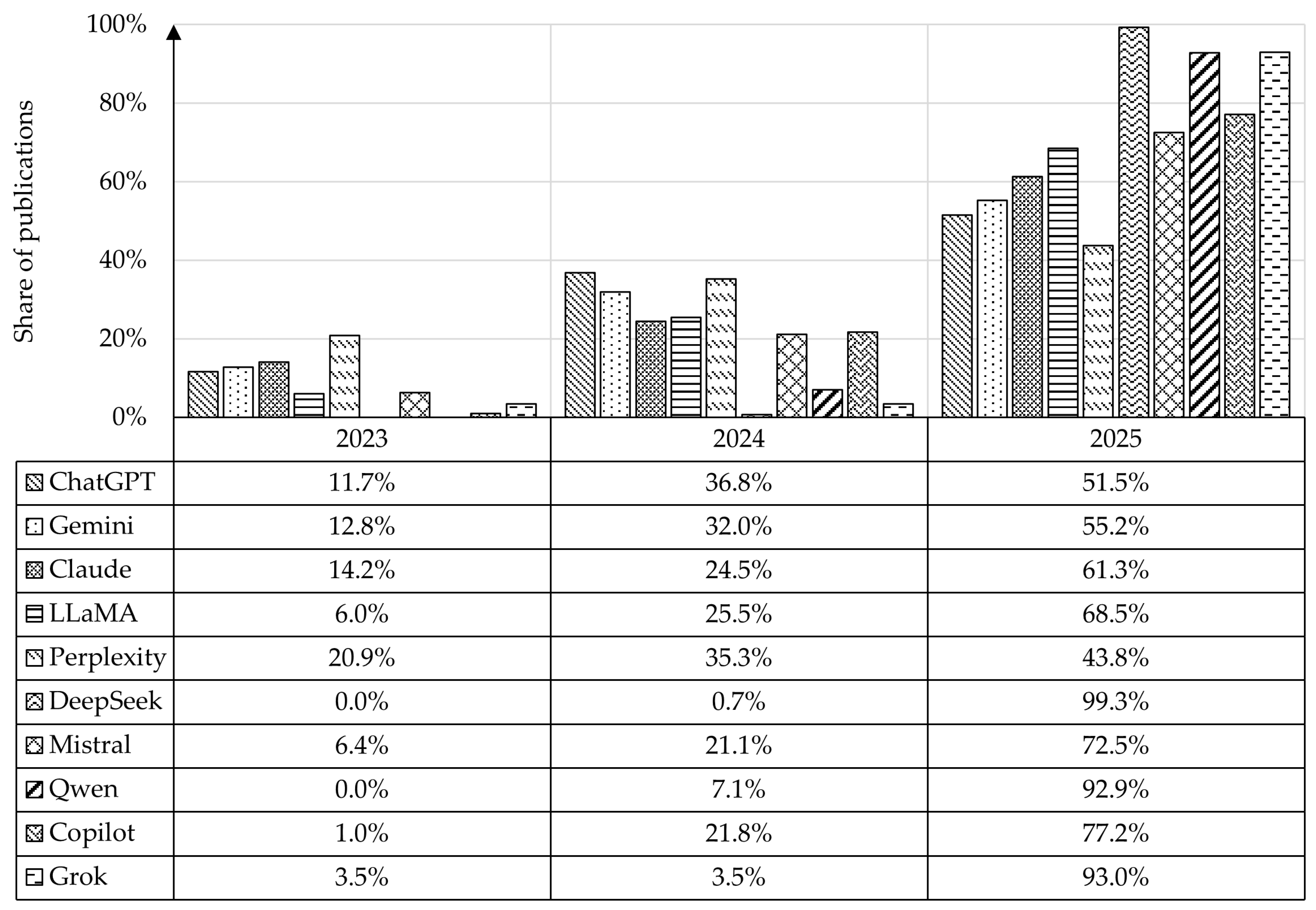

4.1. Analysis of the Number of Publications

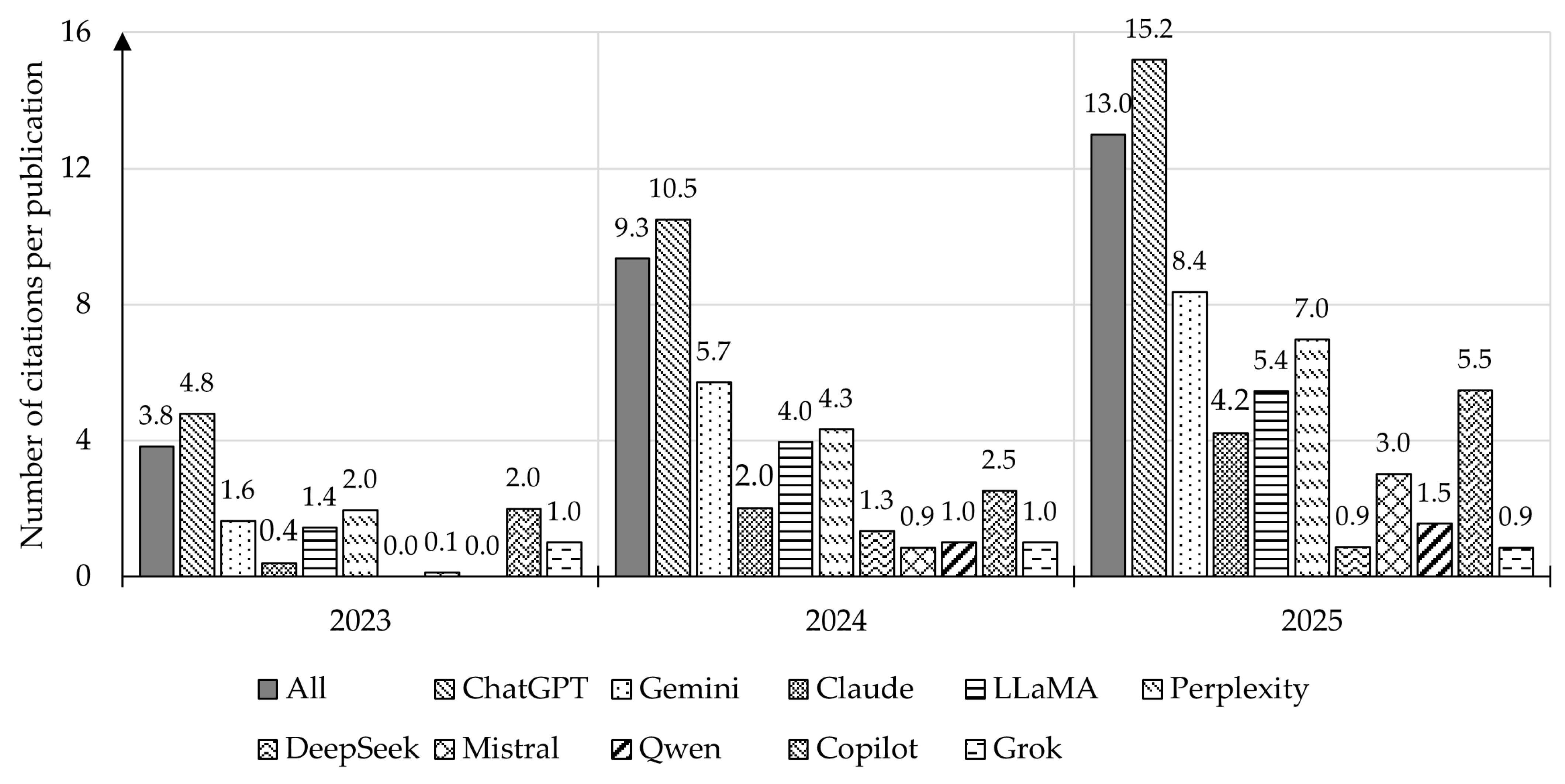

4.2. Analysis of Publication Citations

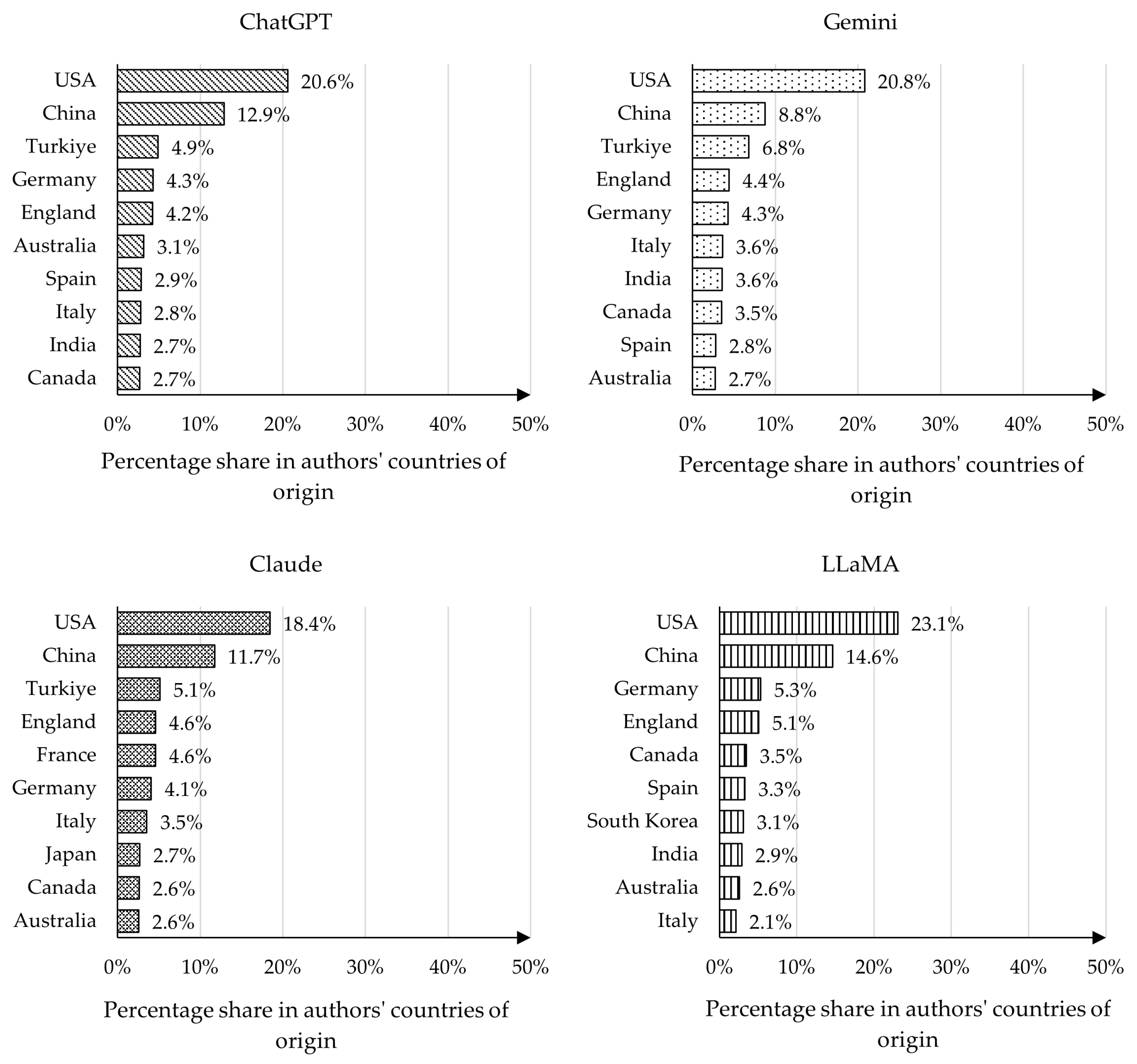

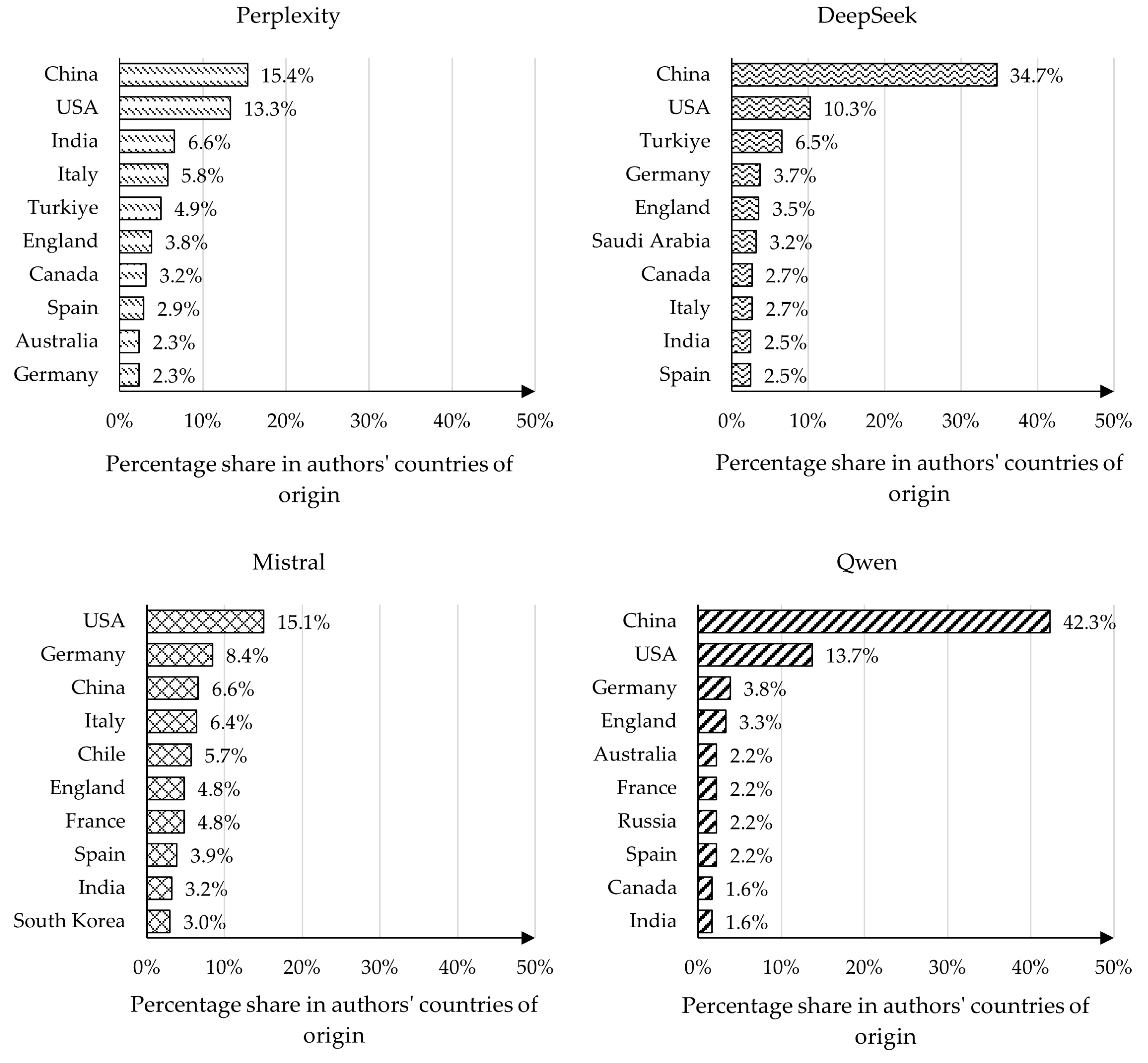

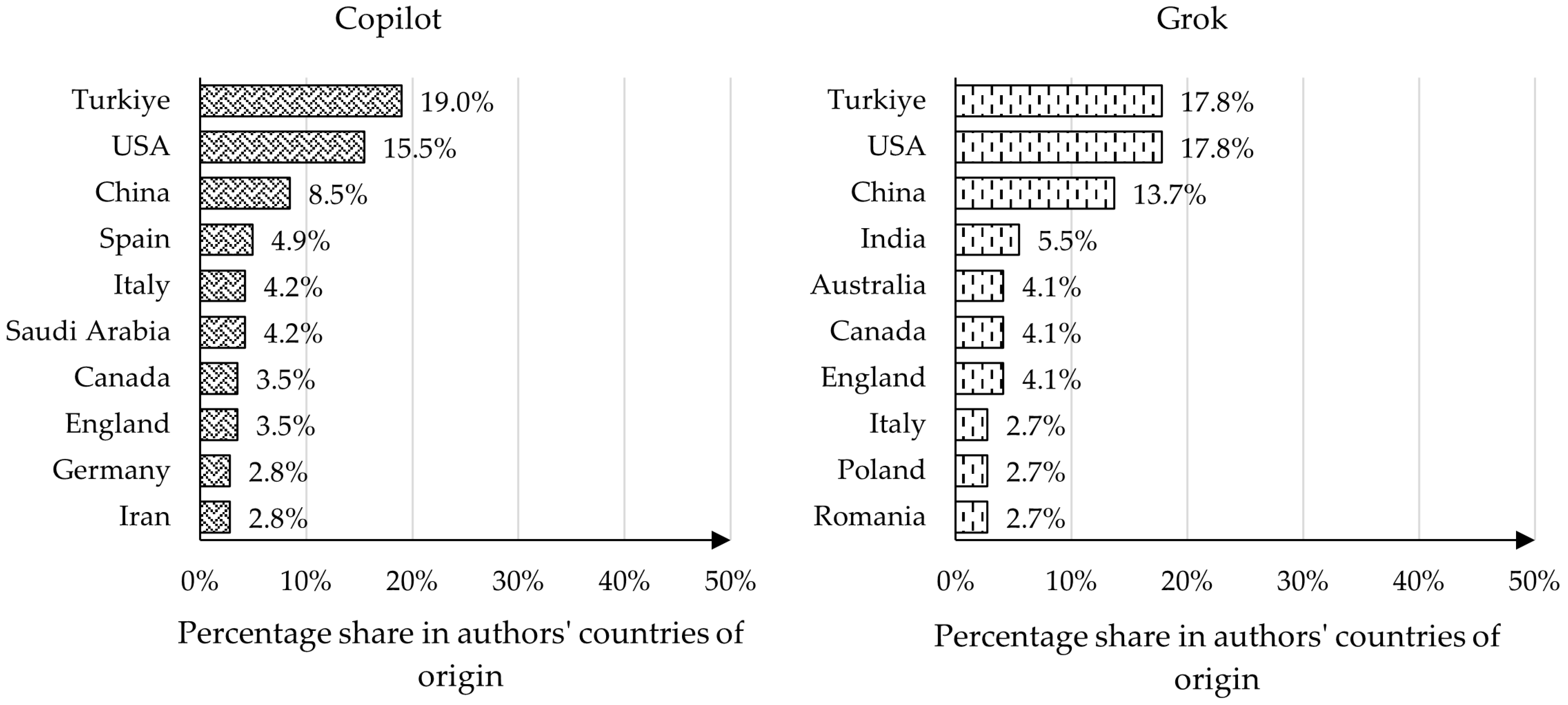

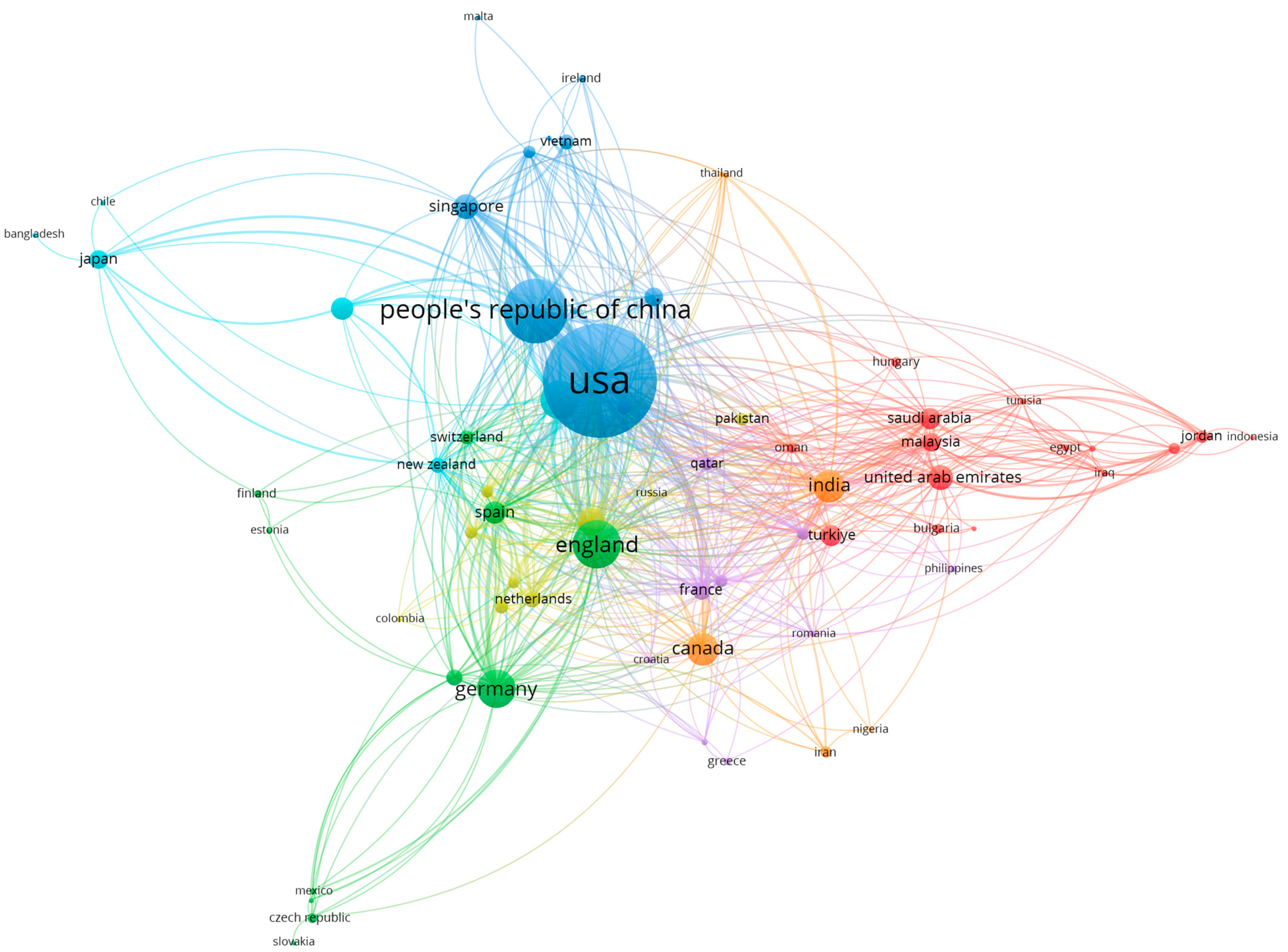

4.3. Analysis of Authors’ Countries of Origin

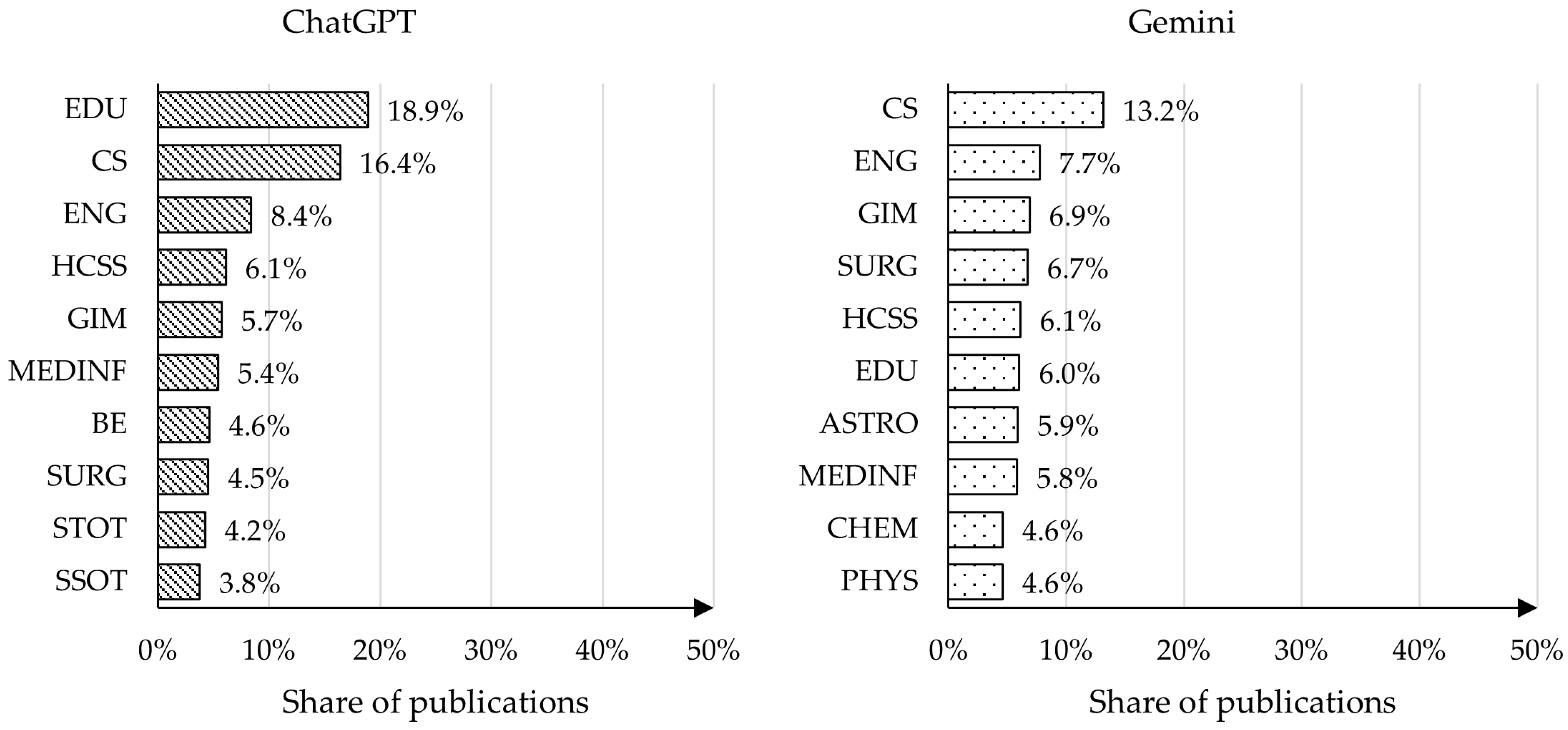

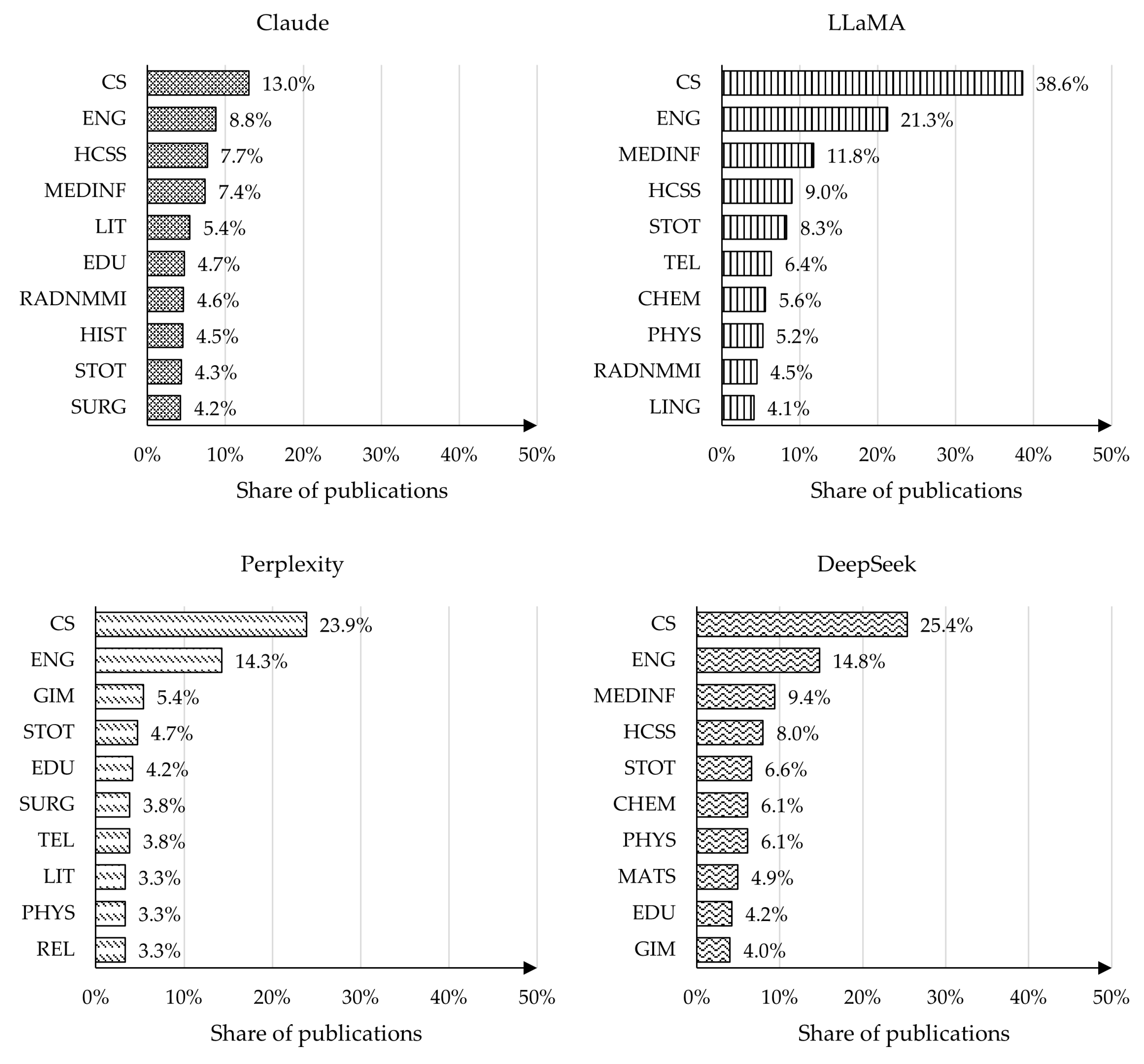

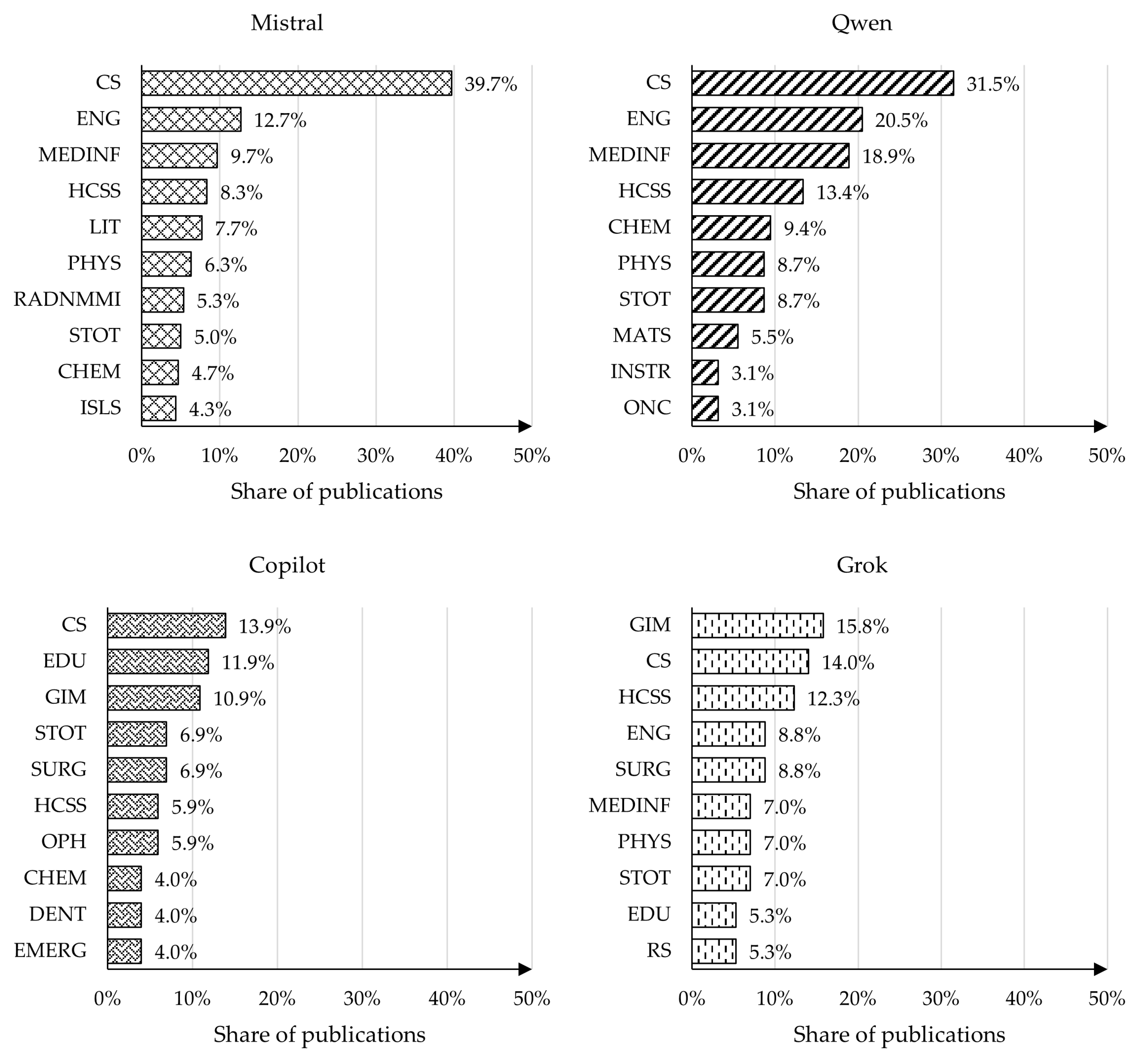

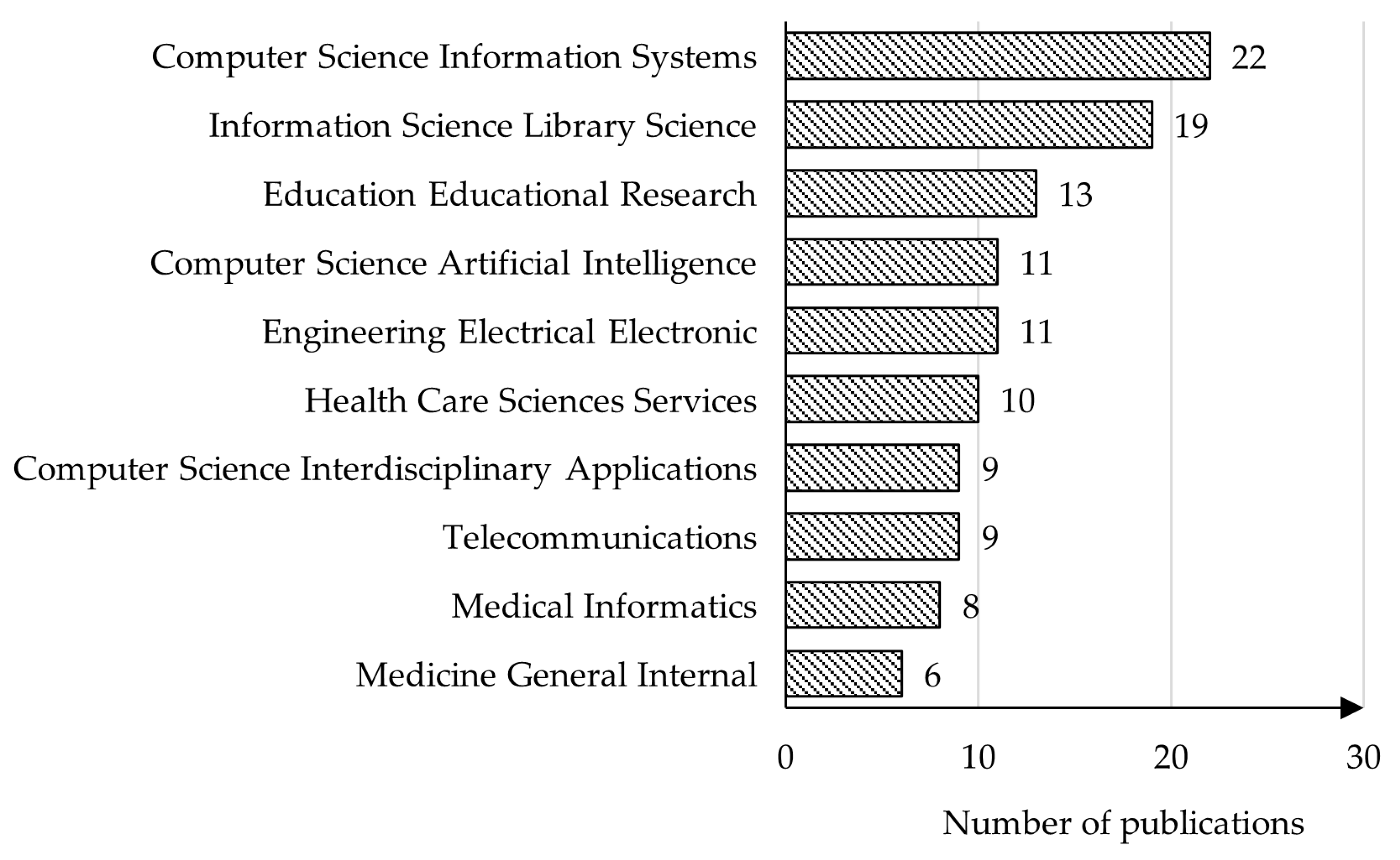

4.4. Analysis of Publication Topics

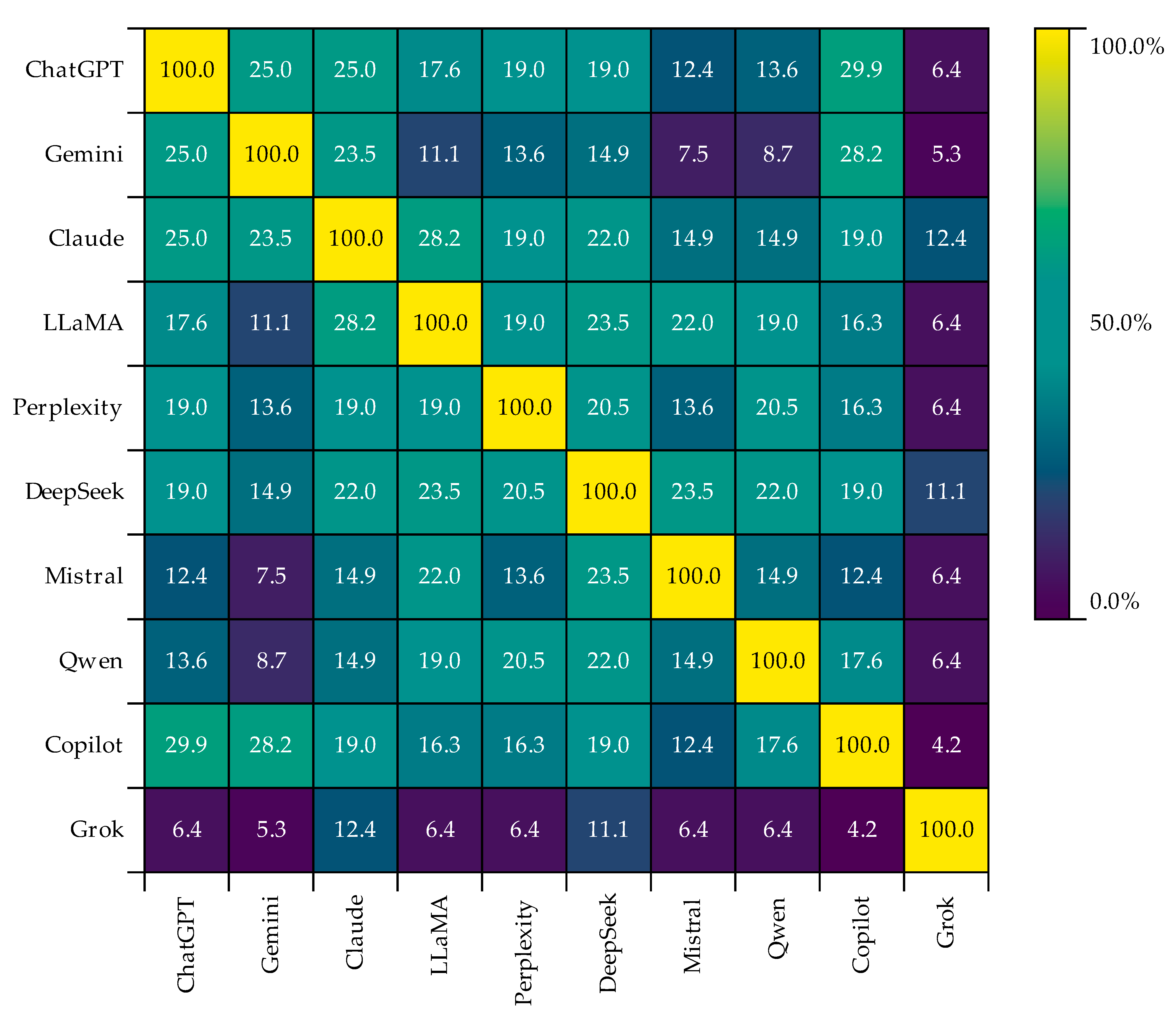

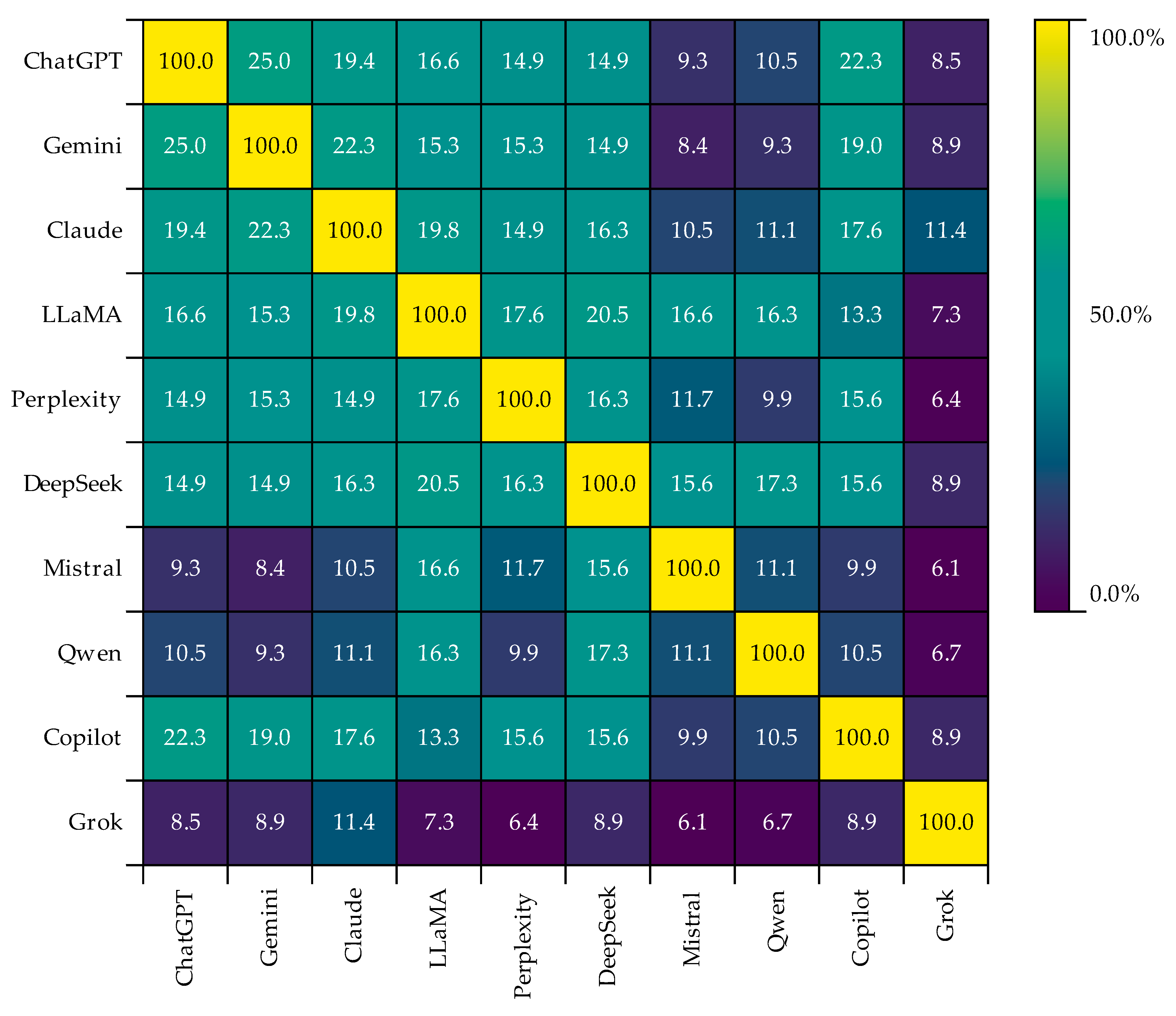

4.5. Analysis of Keywords

5. Discussion

5.1. Differences in the Bibliometric Analysis Across GenAI Tools

5.2. Similarities in the Bibliometric Analysis Across GenAI Tools

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EDU | Education Educational Research |

| CS | Computer Science |

| ENG | Engineering |

| HCSS | Health Care Sciences Services |

| GIM | General Internal Medicine |

| MEDINF | Medical Informatics |

| BE | Business Economics |

| SURG | Surgery |

| STOT | Science Technology Other Topics |

| SSOT | Social Sciences Other Topics |

| PHYS | Physics |

| REL | Religion |

| ASTRO | Astronomy Astrophysics |

| CHEM | Chemistry |

| LIT | Literature |

| HIST | History |

| RADNMMI | Radiology Nuclear Medicine Medical Imaging |

| LING | Linguistics |

| MATS | Materials Science |

| INSTR | Instruments Instrumentation |

| ISLS | Information Science Library Science |

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| ONC | Oncology |

| TEL | Telecommunications |

| DENT | Dentistry Oral Surgery Medicine |

| EMERG | Emergency Medicine |

| OPH | Ophthalmology |

Appendix A. Code for Advanced Search of Bibliometric Studies on LLM in the Web of Science Core Collection Database

Appendix B

| GenAI Name | Code | Number of Publications |

|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT | (TI = (ChatGPT OR “OpenAI ChatGPT” OR “GPT-4o” OR “GPT-4.1” OR “GPT-4.5” OR “GPT-o1” OR “GPT-o3” OR “GPT-o4” OR “o3-mini” OR “o4-mini” OR “GPT-5”) OR TS = (ChatGPT OR “Chat GPT” OR “OpenAI ChatGPT” OR “GPT-4o” OR “GPT-4.1” OR “GPT-4.5” OR “GPT-o1” OR “GPT-o3” OR “GPT-o4” OR “o3-mini” OR “o4-mini” OR “GPT-5” OR (“OpenAI” NEAR/3 ChatGPT) OR (“OpenAI” NEAR/3 GPT))) AND DT = (“Article”) AND PY = (2023 OR 2024 OR 2025) | 11,619 |

| Gemini | (TI = (“Google Gemini” OR “Gemini 2.5” OR “Gemini 2.0” OR “Gemini 1.5” OR “Google Bard” OR Gemini OR Bard) OR TS = (“Google Gemini” OR (Gemini NEAR/3 Google) OR (Gemini NEAR/3 “DeepMind”) OR “Google Bard” OR (Bard NEAR/2 Google) OR Gemini OR Bard)) NOT TS = (zodiac OR astrology OR constellation OR telescope OR observatory OR “Project Gemini” OR NASA OR surfactant* OR amphiphile* OR “Gemini quaternary” OR “Gemini cationic” OR “Gemini ionic liquid*”) AND DT = (“Article”) AND PY = (2023 OR 2024 OR 2025) | 2444 |

| Claude | (TI = (“Anthropic Claude” OR “Claude 4.1” OR “Claude 3.7” OR “Claude 3.5” OR “Claude 3” OR “Claude 2” OR “Claude Sonnet” OR “Claude Opus” OR “Claude Haiku” OR Claude) OR TS = (“Anthropic Claude” OR (Claude NEAR/2 Anthropic) OR Claude)) NOT TS = (“Claude Shannon” OR Monet OR “Claude Bernard” OR “Claude Lévi-Strauss” OR “Claude Levi-Strauss” OR “Saint-Claude”) AND DT = (“Article”) AND PY = (2023 OR 2024 OR 2025) | 1083 |

| LLaMA | (TI = (“Meta Llama” OR “Meta AI” OR LLaMA OR “LLaMA 2” OR “LLaMA 3” OR “Llama 3.1” OR “Llama 4 Scout” OR “Llama 2” OR “Llama 3” OR Llama) OR TS = (“Meta Llama” OR LLaMA OR (“Llama” NEAR/2 Meta) OR Llama)) NOT TS = (animal OR mammal OR camelid OR camelidae OR alpaca OR vicuna OR guanaco OR zoo OR wildlife OR herd OR wool OR fleece OR livestock OR veterinary OR “se llama” OR “llamado” OR “llamada” OR “llamados”) AND DT = (“Article”) AND PY = (2023 OR 2024 OR 2025) | 1067 |

| Perplexity | (TI = (“Perplexity AI” OR Perplexity) OR TS = (“Perplexity AI” OR (Perplexity NEAR/2 “answer engine”) OR (Perplexity NEAR/2 search) OR Perplexity)) NOT TS = ((perplexity NEAR/3 language) OR (perplexity NEAR/3 model) OR (perplexity NEAR/3 NLP) OR (perplexity NEAR/3 metric) OR “Shannon perplexity”) AND DT = (“Article”) AND PY = (2022 OR 2023 OR 2024 OR 2025) | 574 |

| GenAI Name | Code | Number of Publications |

|---|---|---|

| DeepSeek | (TI = (“DeepSeek” OR “DeepSeek-V2” OR “DeepSeek-V2.5” OR “DeepSeek-V3” OR “DeepSeek R1” OR “DeepSeek Coder” OR DeepSeek) OR TS = (“DeepSeek” OR (“DeepSeek” NEAR/3 model) OR (“DeepSeek” NEAR/3 “language model”) OR (“DeepSeek” NEAR/3 “AI assistant”) OR DeepSeek)) AND DT = (“Article”) AND PY = (2023 OR 2024 OR 2025) | 426 |

| Mistral | (TI = (“Mistral Large” OR “Mistral Large 2” OR “Mistral 7B” OR “Mixtral 8x22B” OR “Mixtral 8x7B” OR “Mistral AI” OR Mistral) OR TS = (“Mistral AI” OR “Mistral Large” OR “Mixtral 8x22B” OR (Mistral NEAR/3 “language model”) OR (Mixtral NEAR/3 model) OR Mistral)) NOT TS = (wind OR meteorology* OR Provence OR “Frédéric Mistral”) AND DT = (“Article”) AND PY = (2023 OR 2024 OR 2025) | 300 |

| Qwen | (TI = (“Alibaba Qwen” OR “Qwen 3” OR “Qwen-3” OR “Qwen 2.5” OR “Qwen-2.5” OR “Tongyi Qianwen” OR Qwen) OR TS = (“Alibaba Qwen” OR “Qwen 3” OR “Qwen-3” OR “Tongyi Qianwen” OR (Qwen NEAR/3 Alibaba) OR Qwen)) AND DT = (“Article”) AND PY = (2023 OR 2024 OR 2025) | 127 |

| Copilot | (TI = (“Microsoft 365 Copilot” OR “Copilot for Microsoft 365” OR “Microsoft Copilot” OR Copilot) OR TS = (“Microsoft 365 Copilot” OR (Copilot NEAR/3 “Microsoft 365”) OR (Copilot NEAR/3 “Office 365”) OR (Copilot NEAR/3 Word) OR (Copilot NEAR/3 Excel) OR (Copilot NEAR/3 PowerPoint) OR (Copilot NEAR/3 Outlook) OR (Copilot NEAR/3 Teams) OR Copilot)) NOT TS = (GitHub OR “Git Hub” OR aircraft OR airline OR aviation OR airplane OR “auto pilot” OR autopilot OR UAV OR drone OR cockpit OR pilot OR co-pilot OR “co pilot”) AND DT = (“Article”) AND PY = (2023 OR 2024 OR 2025) | 101 |

| Grok | (TI = (“xAI Grok” OR “Grok-5” OR “Grok-3” OR “Grok-2” OR “Grok-1” OR Grok) OR TS = (“xAI Grok” OR (Grok NEAR/3 xAI) OR (Grok NEAR/3 “Elon Musk”) OR Grok)) NOT TS = (“Grokking” OR “to grok” OR “Grokking Algorithms” OR Heinlein OR “Stranger in a Strange Land”) AND DT = (“Article”) AND PY = (2023 OR 2024 OR 2025) | 57 |

Appendix C

References

- Alavi, M., Georgia Institute of Technology, Leidner, D. E., University of Virginia, Mousavi, R., & University of Virginia. (2024). Knowledge management perspective of generative artificial intelligence. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 25(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J. W., Poliak, A., Dredze, M., Leas, E. C., Zhu, Z., Kelley, J. B., Faix, D. J., Goodman, A. M., Longhurst, C. A., Hogarth, M., & Smith, D. M. (2023). Comparing physician and artificial intelligence chatbot responses to patient questions posted to a public social media forum. JAMA Internal Medicine, 183(6), 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bail, C. A. (2024). Can generative AI improve social science? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(21), e2314021121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banh, L., & Strobel, G. (2023). Generative artificial intelligence. Electronic Markets, 33(1), 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrington, N. M., Gupta, N., Musmar, B., Doyle, D., Panico, N., Godbole, N., Reardon, T., & D’Amico, R. S. (2023). A bibliometric analysis of the rise of ChatGPT in medical research. Medical Sciences, 11(3), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhullar, P. S., Joshi, M., & Chugh, R. (2024). ChatGPT in higher education—A synthesis of the literature and a future research agenda. Education and Information Technologies, 29(16), 21501–21522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkle, C., Pendlebury, D. A., Schnell, J., & Adams, J. (2020). Web of Science as a data source for research on scientific and scholarly activity. Quantitative Science Studies, 1(1), 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolgova, O., Ganguly, P., & Mavrych, V. (2025). Comparative analysis of LLMs performance in medical embryology: A cross-platform study of CHATGPT, Claude, Gemini, and Copilot. Anatomical Sciences Education, 18(7), 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, M. J. (2024). Accelerating scientific discovery with generative knowledge extraction, graph-based representation, and multimodal intelligent graph reasoning. Machine Learning: Science and Technology, 5(3), 035083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, A. (2025, October 17). Best 44 Large Language Models (LLMs) in 2025. Exploding topics. Available online: https://explodingtopics.com/blog/list-of-llms (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Cascella, M., Montomoli, J., Bellini, V., & Bignami, E. (2023). Evaluating the feasibility of ChatGPT in healthcare: An analysis of multiple clinical and research scenarios. Journal of Medical Systems, 47(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C. K. Y., & Hu, W. (2023). Students’ voices on generative AI: Perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D. R. E., Cotton, P. A., & Shipway, J. R. (2024). Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61(2), 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergaa, I., Chamari, K., Zmijewski, P., & Ben Saad, H. (2023). From human writing to artificial intelligence generated text: Examining the prospects and potential threats of ChatGPT in academic writing. Biology of Sport, 40(2), 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L., Li, L., Ma, Z., Lee, S., Yu, H., & Hemphill, L. (2024). A bibliometric review of large language models research from 2017 to 2023. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 15(5), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, F., Silva, E. S., Hassani, H., Madsen, D. Ø., Sohail, S. S., Himeur, Y., Alam, M. A., & Zafar, A. (2024). The scholarly footprint of ChatGPT: A bibliometric analysis of the early outbreak phase. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 6, 1270749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrokhnia, M., Banihashem, S. K., Noroozi, O., & Wals, A. (2024). A SWOT analysis of ChatGPT: Implications for educational practice and research. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61(3), 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gande, S., Gould, M., & Ganti, L. (2024). Bibliometric analysis of ChatGPT in medicine. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 17(1), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwal, A., & Lavecchia, A. (2024). Unleashing the power of generative AI in drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today, 29(6), 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencer, G., & Gencer, K. (2025). Large language models in healthcare: A bibliometric analysis and examination of research trends. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 18, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, A., Safranek, C. W., Huang, T., Socrates, V., Chi, L., Taylor, R. A., & Chartash, D. (2023). How does ChatGPT perform on the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE)? The implications of large language models for medical education and knowledge assessment. JMIR Medical Education, 9, e45312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochmair, H. H., Juhász, L., & Kemp, T. (2024). Correctness comparison of ChatGPT-4, Gemini, Claude-3, and Copilot for spatial tasks. Transactions in GIS, 28(7), 2219–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I., Laskar, M. T. R., Peng, C., & Huang, J. (2023). A comprehensive evaluation of large language models on benchmark biomedical text processing tasks (version 3). arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaftan, A. N., Hussain, M. K., & Naser, F. H. (2024). Response accuracy of ChatGPT 3.5 Copilot and Gemini in interpreting biochemical laboratory data a pilot study. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 8233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, T. H., Cheatham, M., Medenilla, A., Sillos, C., De Leon, L., Elepaño, C., Madriaga, M., Aggabao, R., Diaz-Candido, G., Maningo, J., & Tseng, V. (2023). Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLoS Digital Health, 2(2), e0000198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Sun, J., & Tan, X. (2024). Evaluating the effectiveness of large language models in abstract screening: A comparative analysis. Systematic Reviews, 13(1), 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M., Gunasekara, A., Pallant, J. L., Pallant, J. I., & Pechenkina, E. (2023). Generative AI and the future of education: Ragnarök or reformation? A paradoxical perspective from management educators. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z. (2023). Why and how to embrace AI such as ChatGPT in your academic life. Royal Society Open Science, 10(8), 230658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M. Y., Chen, B., Williamson, D. F. K., Chen, R. J., Zhao, M., Chow, A. K., Ikemura, K., Kim, A., Pouli, D., Patel, A., & Soliman, A. (2024). A multimodal generative AI copilot for human pathology. Nature, 634(8033), 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, G., Prasanna Kumar, R., Krishh, P., Keerthinathan, A., Lavanya, G., Meghana, M. K. U., Sulthana, S., & Doss, S. (2024). An analysis of large language models: Their impact and potential applications. Knowledge and Information Systems, 66(9), 5047–5070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, D., Zhao, X., Chen, C., Sun, S., Lee, K. R., & Kim, J. H. (2025). Bibliometric analysis on ChatGPT research with CiteSpace. Information, 16(1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, H., Khan, A. U., Qiu, S., Saqib, M., Anwar, S., Usman, M., Akhtar, N., Barnes, N., & Mian, A. (2025). A comprehensive overview of large language models. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 16(5), 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazi, Z. A., & Peng, W. (2024). Large language models in healthcare and medical domain: A review (version 2). arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliński, M., Krukowski, K., & Sieciński, K. (2024). Bibliometric overview of ChatGPT: New perspectives in social sciences. Publications, 12(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A., Musheyev, D., Bockelman, D., Loeb, S., & Kabarriti, A. E. (2023). Assessment of artificial intelligence Chatbot responses to top searched queries about cancer. JAMA Oncology, 9(10), 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S., Luo, L., Wang, Y., Chen, C., Wang, J., & Wu, X. (2024). Unifying large language models and knowledge graphs: A Roadmap. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 36(7), 3580–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R., & Gudivada, V. (2024). A review of current trends, techniques, and challenges in Large Language Models (LLMs). Applied Sciences, 14(5), 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, H., Topuz, A. C., Yıldız, M., Taşlıbeyaz, E., & Kurşun, E. (2024). A bibliometric analysis of research on ChatGPT in education. International Journal of Technology in Education, 7(1), 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradana, M., Elisa, H. P., & Syarifuddin, S. (2023). Discussing ChatGPT in education: A literature review and bibliometric analysis. Cogent Education, 10(2), 2243134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. (2021). Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications, 9(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z., Shi, C., Jeon, C. O., Fu, J., Liu, S., Lan, C., Yao, Y., Liu, Y., & Jia, B. (2024). ChatGPT and generative AI are revolutionizing the scientific community: A Janus-faced conundrum. iMeta, 3(2), e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pwanedo Amos, J., Ahmed Amodu, O., Azlina Raja Mahmood, R., Bolakale Abdulqudus, A., Zakaria, A. F., Rhoda Iyanda, A., Ali Bukar, U., & Mohd Hanapi, Z. (2025). A Bibliometric exposition and review on leveraging LLMs for programming education. IEEE Access, 13, 58364–58393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M., Jahangir, Z., Riaz, M. B., Saeed, M. J., & Sattar, M. A. (2025). Industrial applications of large language models. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 13755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, C. H., Kanhere, A., Parekh, V., Langlotz, C. P., Joshi, A., Huang, H., & Doo, F. X. (2025). Open-source large language models in radiology: A review and tutorial for practical research and clinical deployment. Radiology, 314(1), e241073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherbakov, D., Hubig, N., Jansari, V., Bakumenko, A., & Lenert, L. A. (2025). The emergence of large language models as tools in literature reviews: A large language model-assisted systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 32(6), 1071–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M., Basit, A., Karri, R., & Shafique, M. (2024). Survey of different large language model architectures: Trends, benchmarks, and challenges. IEEE Access, 12, 188664–188706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shool, S., Adimi, S., Saboori Amleshi, R., Bitaraf, E., Golpira, R., & Tara, M. (2025). A systematic review of large language model (LLM) evaluations in clinical medicine. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 25(1), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, M., Goyal, I., Gupta, B., & Sharma, J. (2024). A comparative study of ChatGPT, Gemini, and perplexity. International Journal of Innovative Research in Computer Science and Technology, 12(4), 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M. F., Topkaç, E. C., Doğan, Ç., Şeramet, S., Özcan, R., Akgül, M., & Yazıcı, C. M. (2024). Still Using Only ChatGPT? The comparison of five different artificial intelligence chatbots’ answers to the most common questions about kidney stones. Journal of Endourology, 38(11), 1172–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, B. (2025). Performance of five large language models in managing acute dental pain: A comprehensive analysis. Turkish Endodontic Journal, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Fu, T., Du, Y., Gao, W., Huang, K., Liu, Z., Chandak, P., Liu, S., Van Katwyk, P., Deac, A., & Anandkumar, A. (2023). Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature, 620(7972), 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Hu, T., Xiao, H., Li, Y., Zhang, C., Ning, H., Zhu, R., Li, Z., & Ye, X. (2024). GPT, large language models (LLMs) and generative artificial intelligence (GAI) models in geospatial science: A systematic review. International Journal of Digital Earth, 17(1), 2353122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, T. I., Roos, J., & Kaczmarczyk, R. (2023). Large language models for therapy recommendations across 3 clinical specialties: Comparative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e49324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Ma, Y., Wang, J., & Xiao, M. (2024). The application of ChatGPT in medicine: A scoping review and bibliometric analysis. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 17, 1681–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., Zheng, Z., Qiu, Z., Wang, H., Gu, H., Shen, T., Qin, C., Zhu, C., Zhu, H., Liu, Q., Xiong, H., & Chen, E. (2023). A survey on large language models for recommendation (version 5). arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcinkaya, T., & Sebnem, C. Y. (2024). Bibliometric and content analysis of ChatGPT research in nursing education: The rabbit hole in nursing education. Nurse Education in Practice, 77, 103956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L., Greiff, S., Teuber, Z., & Gašević, D. (2024). Promises and challenges of generative artificial intelligence for human learning (version 3). arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R., Zhu, J., Man, J., Fang, L., & Zhou, Y. (2024). Enhancing text-based knowledge graph completion with zero-shot large language models: A focus on semantic enhancement. Knowledge-Based Systems, 300, 112155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S., Fu, C., Zhao, S., Li, K., Sun, X., Xu, T., & Chen, E. (2024). A survey on multimodal large language models. National Science Review, 11(12), nwae403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Wang, Q., Kong, X., Xiong, J., Ni, S., Cao, D., Niu, B., Chen, M., Li, Y., Zhang, R., Wang, Y., Zhang, L., Li, X., Xiong, Z., Shi, Q., Huang, Z., Fu, Z., & Zheng, M. (2024). Fine-tuning large language models for chemical text mining. Chemical Science, 15(27), 10600–10611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Chen, H., Yang, F., Liu, N., Deng, H., Cai, H., Wang, S., Yin, D., & Du, M. (2024). Explainability for large language models: A survey. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 15(2), 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., Pan, Y., Zhang, Y., Song, X., & Zhou, Y. (2025). Evaluating AI-generated patient education materials for spinal surgeries: Comparative analysis of readability and DISCERN quality across ChatGPT and deepseek models. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 198, 105871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X., Li, J., Liu, Y., Ma, C., & Wang, W. (2024). A survey on model compression for large language models. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 12, 1556–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GenAI Name | Most-Cited Publications | i10-Index * | h-Index * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Title | Citation Count | |||

| ChatGPT | Kung et al. (2023) | Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models | 1973 | 10,608 | 136 |

| Gemini | Lim et al. (2023) | Generative AI and the future of education: Ragnarok or reformation? A paradoxical perspective from management educators | 566 | 2816 | 48 |

| Claude | Wilhelm et al. (2023) | Large Language Models for Therapy Recommendations Across 3 Clinical Specialties: Comparative Study | 80 | 486 | 24 |

| LLaMA | Dergaa et al. (2023) | From human writing to artificial intelligence generated text: examining the prospects and potential threats of ChatGPT in academic writing | 308 | 1411 | 30 |

| Perplexity | A. Pan et al. (2023) | Assessment of Artificial Intelligence Chatbot Responses to Top Searched Queries About Cancer | 150 | 701 | 19 |

| DeepSeek | Zhou et al. (2025) | Evaluating AI-generated patient education materials for spinal surgeries: Comparative analysis of readability and DISCERN quality across ChatGPT and deepseek models | 25 | 144 | 9 |

| Mistral | Zhang et al. (2024) | Fine-tuning large language models for chemical text mining | 39 | 225 | 12 |

| Qwen | Yang et al. (2024) | Enhancing text-based knowledge graph completion with zero-shot large language models: A focus on semantic enhancement | 21 | 108 | 8 |

| Copilot | Lu et al. (2024) | A multimodal generative AI copilot for human pathology | 148 | 336 | 10 |

| Grok | Şahin et al. (2024) | Still Using Only ChatGPT? The Comparison of Five Different Artificial Intelligence Chatbots’ Answers to the Most Common Questions About Kidney Stones | 13 | 55 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sieciński, K.; Oliński, M. A Multidisciplinary Bibliometric Analysis of Differences and Commonalities Between GenAI in Science. Publications 2025, 13, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications13040067

Sieciński K, Oliński M. A Multidisciplinary Bibliometric Analysis of Differences and Commonalities Between GenAI in Science. Publications. 2025; 13(4):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications13040067

Chicago/Turabian StyleSieciński, Kacper, and Marian Oliński. 2025. "A Multidisciplinary Bibliometric Analysis of Differences and Commonalities Between GenAI in Science" Publications 13, no. 4: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications13040067

APA StyleSieciński, K., & Oliński, M. (2025). A Multidisciplinary Bibliometric Analysis of Differences and Commonalities Between GenAI in Science. Publications, 13(4), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications13040067