1. Introduction

Universal laws for citations have been among the most discussed topics in the academic community over the past decades (

Hirsch, 2005;

Laherrère & Sornette, 1998;

Redner, 1998). Rankings, in turn, constitute another fundamental concept for the academic community, as they permeate several processes, ranging from university rankings to, for example, the admission of students to universities

da Silva et al. (

2016), and, in a bibliometric context, to the classification of researchers

Batista et al. (

2006). Bibliometric rankings can also be useful for allocating research grants in a fair manner and for assessing journals according to the quality of their editorial boards. In the scope of this paper, the term

quality refers to research output as measured by scientific publications. Thus, how authors’ citations can be captured to build such bibliometric rankings is a problem that deserves careful attention.

Numerical data on the distribution of citations has been extensively explored by the scientific community, and universal laws have been established. Based on the ISI (Institute for Scientific Information) database,

Laherrère and Sornette (

1998) suggest that the number of papers with

x citations decays as a power law

where

. Similarly,

Redner (

1998) found a stretched exponential form

with

when analysing data from the 1120 most-cited physicists between 1981 and 1997. On the other hand,

Tsallis and de Albuquerque (

2000) showed that citation distributions are well described by curves derived from nonextensive formalism.

Hirsch (

2005) reduced the complexity of the data distribution to quantify the importance of a scientist’s research output into a single measure known as the

h-index. Despite being controversial, the

h-index is widely employed by many research funding agencies and universities all over the world. Hirsh’s simple idea is that a publication is good as long as it is cited by other authors; i.e., “a scientist has index

h if

h of their

papers has at least

h citations each. The other (

) papers have

citations each, with

.”

There are alternatives to the use of the

h-index;

Braun (

2004), for example, uses the total number of citations to quantify research performance. However, in this paper, we have opted to use the

h-index because it is less prone to being inflated by a small number of big hits or by the eminence of co-authors. Since its proposal, it has become widely accepted and has been employed as the basis for many scientometrics and bibliometrics research. Moreover, since it is a flexible index, authors explore its range. For example, the authors of

Batista et al. (

2006) show that accounting for the number of coauthors in the

h-core papers used to compute a researcher’s

h-index makes it possible to compare researchers across different scientific fields.

In recent decades, bibliometrics has evolved substantially in the domains of equity and diversity indicators, modern normalization methods, network-based approaches, and epistemological reflections on research evaluation.

Concerning

equity and diversity, the discussion has been greatly shaped by the

Leiden Manifesto, which proposes ten principles to guide the responsible use of research metrics and to promote fairness, transparency, and contextualization in evaluation processes (

Hicks et al., 2015). These principles are essential to mitigate systemic biases and to avoid reinforcing structural inequalities in scientific assessment.

Regarding

modern citation normalization, Waltman and van Eck provided both a conceptual classification and detailed empirical analyses. Their work on source-normalized indicators demonstrates that these methods often outperform traditional field-normalized metrics, as they are better suited to handle the diverse citation practices across scientific fields

Waltman and van Eck (

2013a,

2013b). These contributions remain among the most influential in contemporary citation normalization research.

In the area of

network- and collaboration-based approaches, Newman’s studies on scientific collaboration networks revealed that co-authorship structures display small-world properties, strong clustering, and characteristic patterns of connectivity (

Newman, 2001). Extended analyses further explored temporal evolution, centrality measures, and distances among researchers, providing a deeper understanding of how scientific communities are organized (

Newman, 2004). Other authors (

Silva et al., 2013) have used network-based bibliometric analyses to quantify the interdisciplinarity of scientific journals and research fields.

From an

epistemological perspective, Biagioli and Lippman’s edited volume

Gaming the Metrics investigates how metric-based evaluation systems can generate perverse incentives, leading to misconduct, citation rings, and other forms of strategic manipulation (

Biagioli & Lippman, 2020). That work highlights the non-neutral nature of metrics and their interaction with institutional pressures. Similarly, Moed and Halevi argue for the need for a multidimensional assessment framework, showing that no single metric can adequately capture the complexity of scientific performance and that different indicators are relevant for different evaluation contexts (

Moed & Halevi, 2015).

Together, these contributions illustrate the richness and complexity of contemporary bibliometric scholarship, emphasizing that responsible research evaluation requires a combination of quantitative indicators, qualitative judgment, epistemic awareness, and sensitivity to equity.

In this context, the importance of analyzing groups of researchers is evident, as such evaluations are directly related to the distribution of research grants, the composition of editorial boards, the assessment of postgraduate programs, and other institutional processes. Among recent works, we can mention the study of university chemistry groups in the Netherlands, which shows how group performance correlates with journal impact (

van Raan, 2012). In their study,

Thaule and Strand (

2018) compare normalization methods and bibliometric evaluation approaches.

Rosas et al. (

2011) apply bibliometric methods to clinical trial networks funded by a U.S. agency, assessing their research presence, performance, and impact. This study addresses the evaluation of large-scale research programs, which can be particularly useful if the analyzed “group” represents a broader program or consortium.

Biagetti (

2022) critically discusses the use of bibliometric indicators and advocate for their complementarity with peer review and other qualitative methods.

The problem addressed in the present work is how to characterize and classify a group of researchers by quantitatively analyzing the h-indexes of its individual members. The method we propose assumes that quality cannot be characterized just by a high average h-index for the group, but also by its homogeneity. Our rationale is that a group can have a high average h-index just by having one very productive researcher. However, a homogeneous group with an equivalent h-index will be better, as homogeneity denotes greater robustness of the group.

We introduce a method to measure the scientific research output of a group of researchers. The proposed method quantifies the quality of a group using a parameter that we call the α-index. The α-index of a group is based on two concepts:

The h-group, which is an extension of the h-index for groups. It is measured by taking the maximum number of researchers in the group, satisfying h-index ≥ h-group. The remaining researchers in the group have h-index < h-group.

An important aspect in the fields of computer science and engineering is that not only journal publications are valued; qualified conferences and workshops also play a crucial role

Zhuang et al. (

2007). Consequently, assessing the quality of conferences is essential for an adequate evaluation of a researcher’s output. In this work, we show how the proposed

α-index can be applied, first, to evaluate the quality of a conference based on the

h-indexes of the members of its Technical Program Committee (TPC), and, second, to examine a completely different context: Brazilian postgraduate programs (BPPs) in Physics–also through the

h-index of their members, whose scientific production is predominantly based on journal publications.

Our method was designed to enable fair comparisons between groups of different sizes, making it suitable for analyzing both TPCs and BPPs. The results obtained with the proposed α–index are consistent: the relative ordering of the groups remains stable even when considering subsets or supersets of the full set of groups.

In our analysis, we gathered and organized bibliometric data for the seven conferences held in 2007 and for the nine postgraduate programs evaluated in 2010. This dataset includes the individual h-index of each TPC and BPP member, as well as the citation counts of their publications.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents a pedagogical study of bibliometric data using the information collected from the seven conferences. We discuss several stylized facts regarding citation and

h-index distributions, in order to verify whether the dataset reproduces the universal bibliometric patterns reported in the literature. We also present the classification of these conferences according to CAPES (

http://www.capes.gov.br, accessed on 28 September 2007), the Brazilian agency responsible for evaluating the quality of graduate programs (

Almeida Guimarães & Chaves Edler de Almeida, 2012;

Lima, 2025).

Section 3 shows that the Gini coefficient is a natural measure of the homogeneity of the program committees of scientific conferences, by analogy with the homogeneity of wealth distribution in a population. We also define the concept of the

h-group. These two notions allow us to define the index that will be explored in our results: the group’s

α-index.

It is important to note that

Section 2 and

Section 3 serve as preparatory material. For simplicity, these sections use only the TPC dataset to illustrate the concepts and statistical methods introduced. After this groundwork is established, we turn to our main quantity, the

-index, and analyze it in detail using both datasets. The results for TPCs and BPPs are then presented separately in

Section 4 and

Section 5, respectively.

First, we analyze the TPCs in computer science. We compute the

-index for each conference and perform ranking tests based on the CAPES classification. Then, to complement this analysis—and to show that the index can be applied consistently across different contexts—we present a second application that serves as a validation of the approach, calculating the

-index for the BPPs in Physics. In this case, we briefly describe the dataset, compute the

-index, and show that it also aligns well with the CAPES ranking (accessed at

http://www.capes.gov.br on 17 June 2010), similarly to what was observed for the TPCs. Finally,

Section 6 presents the conclusions and outlines possible extensions of the model.

The results indicate that the methodology is effective for both datasets, showing a strong correlation with the CAPES classification.

2. Preliminaries, Descriptive Statistics, and Stylized Bibliometric Facts: The Case

of Computer Science Conferences

The data used for the TPCs in this study refer to an earlier period (2007), and the corresponding analyses were refined continuously up to the present submission. Although the dataset is not up to date, this choice ensures that it is unaffected by distortions arising from the COVID-19 pandemic or other external factors. The resulting h-index values thus reflect the conditions of that period and should not be interpreted as representative of the currently inflated citation rates or the recent surge in scientific output. For ethical reasons, the names of universities, conferences, locations, and individual researchers have been omitted to preserve the privacy and integrity of all parties involved.

CAPES has defined a system for classifying the estimated quality of publication venues. The system is called Qualis, and it grades venues into three categories: A, B, or C. According to this grading scheme, A is the highest quality, and it is usually assigned to top international conferences. The criteria analysed include the number of editions of the conference and its acceptance rate.

Table 1 presents the data collected for seven conferences, all corresponding to the same validity period as the official ranking. The

h-indexes were obtained using the free software *Publish or Perish* (

http://www.harzing.com/resources.htm, accessed on 28 September 2007), which extracts citation data from the Google Scholar service (

http://scholar.google.com, also accessed on 28 September 2007).

As a starting point, we explore some preliminary statistics about these conferences. It is interesting to check similarities between the properties obtained from the TPC population and the properties expected from the general scientific population. The first analysis was to plot the number of citations to papers written by the TPC members as a function of their

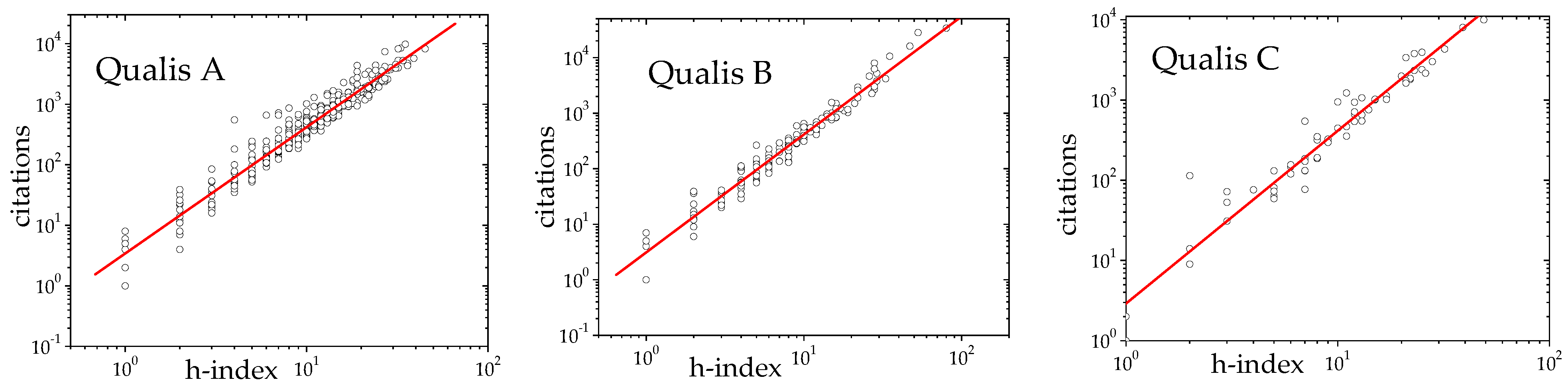

h-indexes. These plots are shown in

Figure 1.

In all cases presented in

Figure 1, we found that the number of citations the authors have has a quadratic dependence on their h-indexes, as obtained in scientific databases such as ISI (see, for example,

Laherrère and Sornette (

1998);

Redner (

1998)). In order to measure the

exponent, we separated our data according to the classification of the conference (A, B or C) assigned by CAPES. For each set of conferences, we analysed the expected relation

, where

x is the number of citations of the author and

h is the corresponding

h-index. In a log–log plot, shown in

Figure 1, we measured the slope. The results were

, 2.12(3), and 2.15(6) for conferences A, B, and C, respectively. This result corroborates Hirsh’s theory (

Hirsch, 2005), in which

.

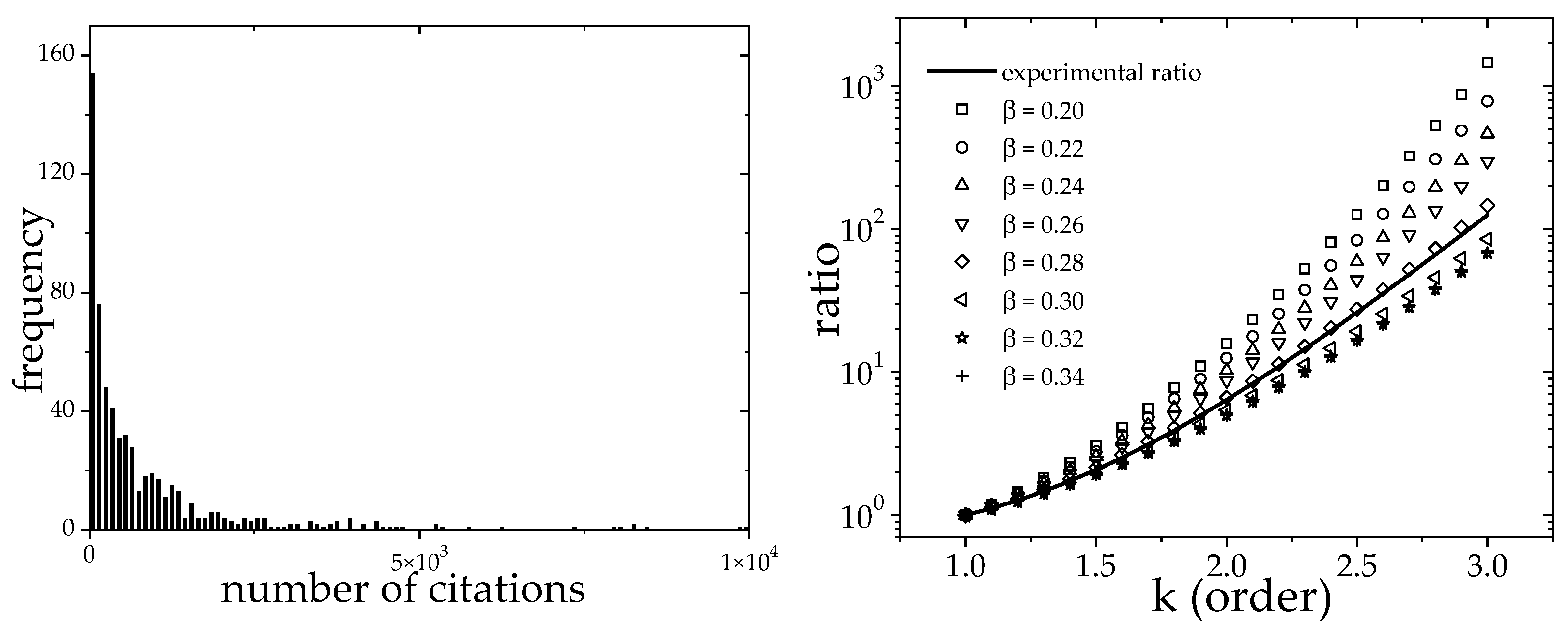

We analyzed the distribution of citations in order to compare the features of our data against the properties found in other scientific populations. The analysis takes all TPC members into consideration (combining A, B, and C conferences). The idea was to verify whether the distribution of the number of citations, denoted by

x, for TPC members of computer science conferences follows a stretched exponential form:

as claimed by Laherrere and Sornette in (

Laherrère & Sornette, 1998). In their study, they found

, which can be determined by plotting a histogram with the number of citations (

x), as shown in

Figure 2 (left plot).

Estimating

directly from the data in

Figure 2 (left plot) can be achieved by determining the slope of the linear fit of

versus log x. Nevertheless, this procedure may yield imprecise results. Therefore, we propose looking at the exact ratio

, where

are the moments of the distribution given by Equation (

1). For example, when

,

corresponds to the average of the distribution given by Equation (

1). The solution we adopted was to vary

so as to find the best approximation to

in relation to the experimental ratios

calculated by Equation (

3). Thus, the values for

can be analytically calculated and do not depend on the parameter

:

where

is the gamma function

.

We then calculate

for values of

k between 1 and 3, using a lag of

, and different values of

(see right plot in

Figure 2) were considered in the search for a best match to the experimental ratio

given by Equation (

3).

where

n denotes the number of TPC members and is represented by a continuous curve in the same plot. We can observe that the best match is found when

, corroborating the expected behavior as described in

Laherrère and Sornette (

1998).

This brief analysis shows that the statistical properties related to the distribution of the number of citations and its relationship with the h-index are similar to what was observed in other scientific societies.

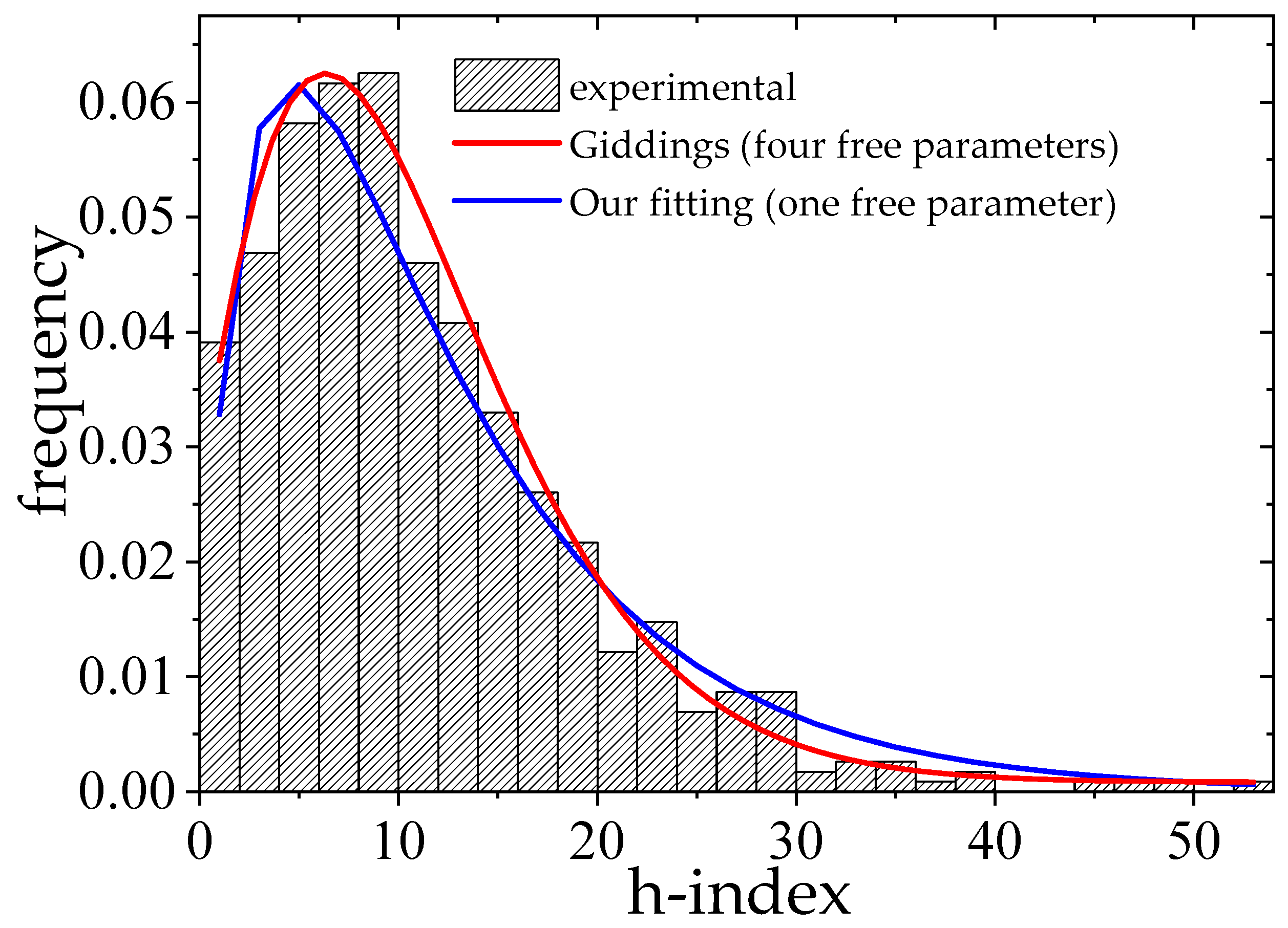

Let us also analyze some aspects related to the

h-index distributions from TPC members of computer science conferences. A histogram of the

h-index for all collected conferences is illustrated in

Figure 3. Many empirical fits were tested (log-normal, gamma, and other non-symmetric functions). Because of the characteristics of the data, a normal fit was not attempted. An excellent fit was found by using a function that comes from the Chromatography literature, known as Giddings distribution (

Giddings & Eyring, 1954), defined in the following equation:

where

is the modified Bessel function, which is described in the integral form by

. Apart from the difficulty in analytically evaluating this function, the fit is numerical and easy to be performed. The fitted values were

,

,

, and

. The function given by Equation (

4) is the distribution in

t, representing the chance that one solute molecule will be eluted from the bottom of the column in a phenomenon of passage of substances through a chromatographic column (see

Giddings and Eyring (

1954) for further details). However, fitting a distribution with four parameters is not simple. A more intuitive formula is to consider the citation distribution given by Equation (

1). By considering Hirsh’s relation

, using (

1) followed by normalization, we obtain an

h-index distribution as given by

da Silva et al. (

2012):

Thus, by considering a simple linear fit in a plot of

x as function

we obtain the slope

a that for our conferences is

(recalling the Hirsch relation,

). Since we also have

previously calculated, varying

(from

to

) we find the best fit, denoted by the blue curve in

Figure 3. The best value found for

by minimizing the least square function was

.

is the same gamma function already described in Equation (

2).

The results of this analysis show a non-symmetric distribution of the

h-index in the program committee of the conferences. However, is this indeed a good feature? In fact, we expect a good conference to have a homogeneous committee composed of young promising researchers with good

h-indexes and also experienced researchers with a good

h-index achieved through a sound scientific career. We do not consider a TPC composed of a few leading scientists padded up with lower-qualified researchers good. Thus, in a second investigation, we analyze the

h-index distribution for each conference. First, it would be interesting to know if any of the conferences present a normal distribution of the h-indexes of their TPC members. Using a traditional Shapiro–Wilk (SW) normality test (see results in

Table 2), we tested the normality level of each conference studied. The conferences Conf. F and Conf. C (the latter is normal at a much lower level) were considered to be normally distributed, at a level of 5%.

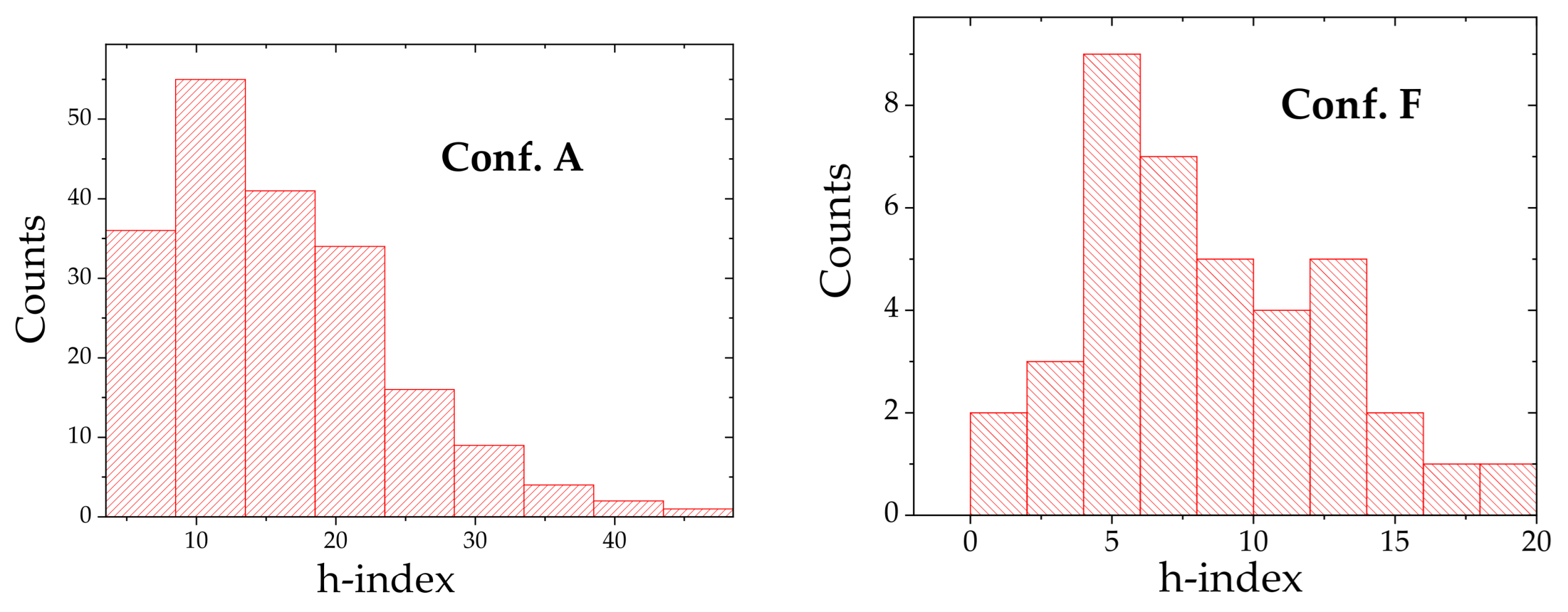

Figure 4 shows a graphical comparison between the

h-index histogram for Conf. F, which is remarkably normal, and for Conf. A, which is remarkably non-normal.

Table 2 also shows some other statistics. The third column presents the

p-values (the greatest value to be attributed to type 1 error for which the normality test would not be rejected). The fourth column shows the kurtosis, which is calculated as in Equation (

6), and measures the weight of the tail of the distribution. The fifth column shows the skewness, which is calculated as in Equation (

7), and measures the symmetry of the distribution.

For a Gaussian distribution, we expect kurtosis and skewness to approach zero. We can observe that Conf. A is a conference that does not follow a normal distribution, characterized by a high

p-value (0.0000), which is more expected of a natural

h-index distribution. It presents a heavy tail (kurtosis = 9.57315) and a good asymmetry (skewness = 1.99863) in relation to its mean value. As we report in

Section 4, Conf. A is the best among the conferences analyzed with our proposed

index.

There is no conclusive indication regarding the relationship between the normality of the TPC

h-index distribution and the quality of the conference. However, according to our method (presented in the

Section 3) the best conferences are predominantly non-normal. This suggests that good conferences will likely have many researchers with high

h-indexes (a characteristic of heavy-tailed distributions), despite many of the

h-indexes being concentrated around a mean value. Normality is an interesting aspect, but it is not the most adequate to determine quality. A good metric must take into consideration the homogeneity of a group, but, at the same time, it cannot lose focus of the magnitude of

h-indexes of the members. It is also important to allow comparisons among groups of different sizes.

Homogeneity, together with a reasonable

h-index definition for groups (see

Egghe (

2008);

Schubert (

2007)), is the main requirement for a good research group, such as a TPC, a postgraduate program, or even the editorial board of a journal. These aspects are explored in greater detail in the next sections.

3. The Gini Coefficient and the h-Index of a Group

The notion of a high-quality group, in any context, presupposes the excellence of its individual members. In certain cases, however, it is not sufficient for a group to include merely a few highly productive individuals alongside others with limited academic output. Homogeneity—understood as a consistent level of academic productivity among members—is also a desirable attribute. This is particularly relevant for research groups such as program committees (TPCs) and editorial boards, where a more homogenous level of expertise contributes to the fairness and consistency of paper evaluations.

We suggest that homogeneity enhances the credibility and effectiveness of such evaluative bodies. Admission to a journal’s editorial board or a conference’s TPC should therefore be contingent upon the researcher having attained a scholarly profile commensurate with the quality standards of the venue. Given that publication venues vary in their academic rigor, participation as a reviewer or committee member should not be assumed as a default entitlement, but rather earned through demonstrated academic achievement appropriate to the venue’s expectations. An interesting statistic to measure the equality of members in a group comes from the Social Economics literature, the Gini coefficient (

Gini, 1921;

Lopes et al., 2011).

In its original formulation, the Gini coefficient (which is a number in the interval [0, 1]) was designed to quantify inequalities in the distribution of wealth within a country. The lower the Gini coefficient, the more equal the wealth distribution. The highest known Gini coefficient is Namibia’s (0.707) while the lowest is Iceland’s (0.195) (

Dorfman, 1979). It is worth mentioning that a low Gini coefficient is positive for a country in which the population has buying power. Remarkably, countries such as Austria and Ethiopia have the same Gini coefficient of 0.300. However, this low Gini coefficient means something good for Austria (a homogeneously high living standard), but it means something bad for Ethiopia (a homogeneously low living standard). However it is impressive how flexible this value is, since its application extends to the physics of phase transitions and critical phenomena, and it is used, for example, to characterize condensates that emerge in the flux of particles in counterflowing (

Stock et al., 2019).

To adapt the method for calculating the Gini coefficient to this bibliometric context, we proceed as follows: first, rank the members of the population in increasing order of “wealth” (here represented by the h-index), i.e.,

. Next, define

as the fraction of “bibliometric wealth” associated with the fraction of individuals

, which is given by

By applying Equation (

8) to each group, the Lorenz curve (

Gastwirth, 1972)

is generated. In a totally fair society (or TPC), we should expect

, but in real societies this is not observed. From that, we extend the Lorenz curve concept to describe inequalities in the

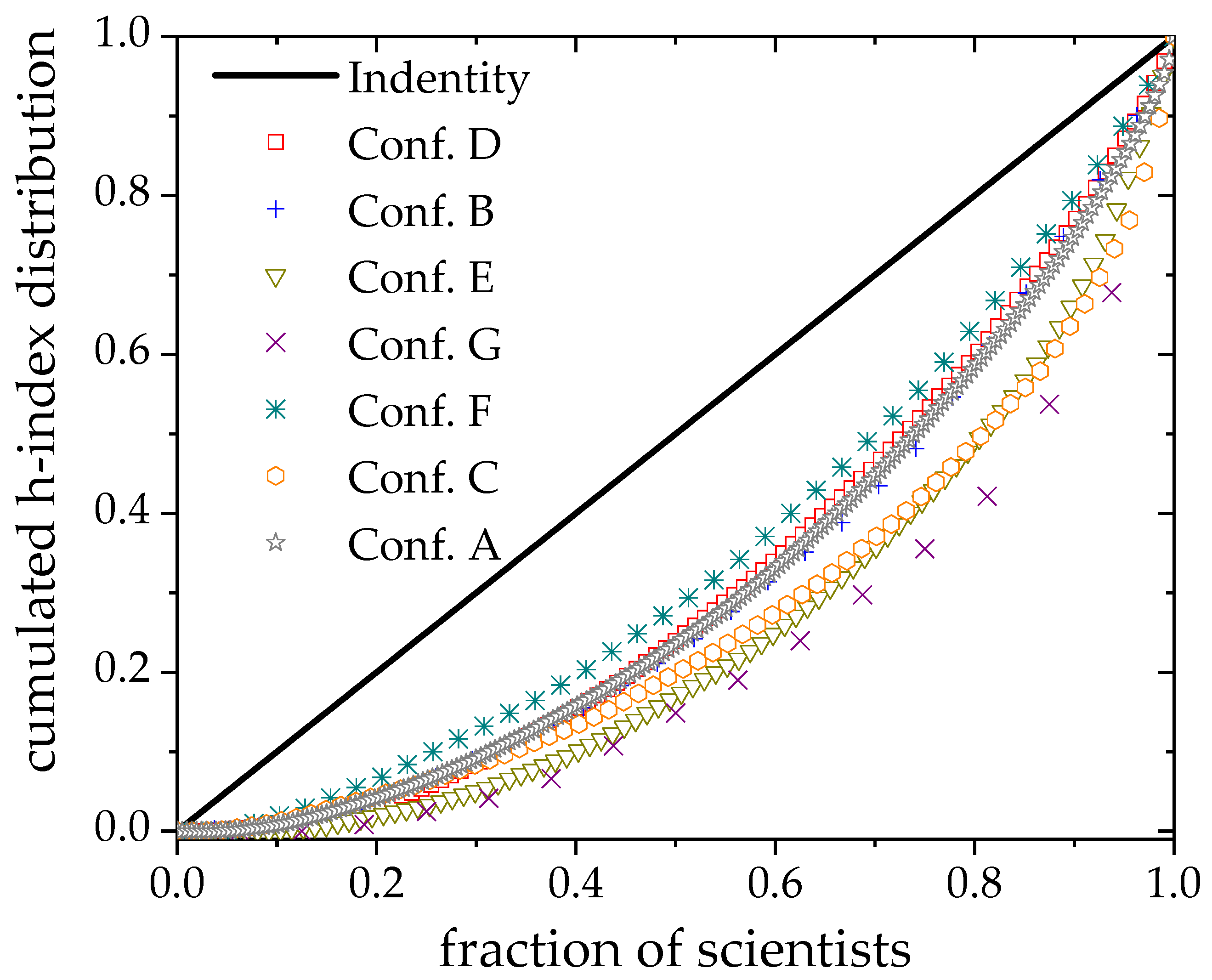

h-index distribution of the scientific population, which is presented for the seven conferences analyzed in this paper in

Figure 5.

We can observe that for each group, the area between the Lorenz curve for each conference and the perfect

h-index distribution represented by the continuous line (identity function

) measures the level of inequality in the conference’s TPC. This notion can be quantified by Gini statistics or simply by the Gini coefficient. The value of the Gini coefficient is twice the aforementioned area. Theoretically, this coefficient is calculated as in Equation (

9):

Equation (

9) is numerically approximated by a trapezoidal formula, leading to Equation (

10):

where

and

for construction.

A simpler formula (without directly calculating the Lorenz curve) can be used to compute the Gini coefficient. Suppose we have a set of h-indexes for a group:

. An estimator for the Gini coefficient is given by:

where

values are ordered in non-decreasing order, and

is the mean of

.

For a simple example, consider

and

. Then

and

This illustrates that the group has a relatively high inequality in the distribution of h-indices.

Our proposed method to classify the quality of a group of researchers from the h-indexes of its members considers the magnitude of the h-index and the level of equality of this h-index in the entire TPC population. This new definition, which we call the “α-index” is composed of two different quantities: (i) the Gini coefficient of the h-index population, and (ii) a definition of the relative h-index.

We consider that the h-index of a group with n members should be established by the maximum number of members that have an h-index equal to or higher than an integer , and necessarily the remaining () members have an h-index less than .

For example, consider the same three h-index values used in the previous Gini coefficient example:

. Ordered in ascending order, we have

,

, and

. Then, for each

i, we compute

versus

, giving the following points:

To determine , we find the largest integer h, such that at least h members satisfy . In this case,

Therefore, for this group, we have

meaning that there are two members with

h-index greater than or equal to 2, but fewer than three members with

h-index .

Up to this point, one may regard

as the second-order value of the successive

h-index introduced by

Egghe (

2008) and

Schubert (

2007). However, in what follows, we go beyond this notion to formulate our final metrics.

The groups to be compared may have different numbers of members. Thus, to compare different groups, we need to define a relative

that can be based on the smallest group to be compared. Let us consider the simplest situation: two groups

and

with sizes, respectively, denoted by

and

, with

. Denoting

as the set of

h-indexes of members of group

, we define the relative

of

in relation to

, over a number of samples (

) as the value calculated by Equation (

12):

where

denotes the

j-th

h-index sample of size

randomly chosen in

. This normalization is required because the group

theoretically should have a maximum

h-index , whereas

cannot match that value because it has fewer members. It is important to mention that our definition requires the gathering of samples of “smallest group size” inside of larger groups in a way that groups of different sizes can be compared.

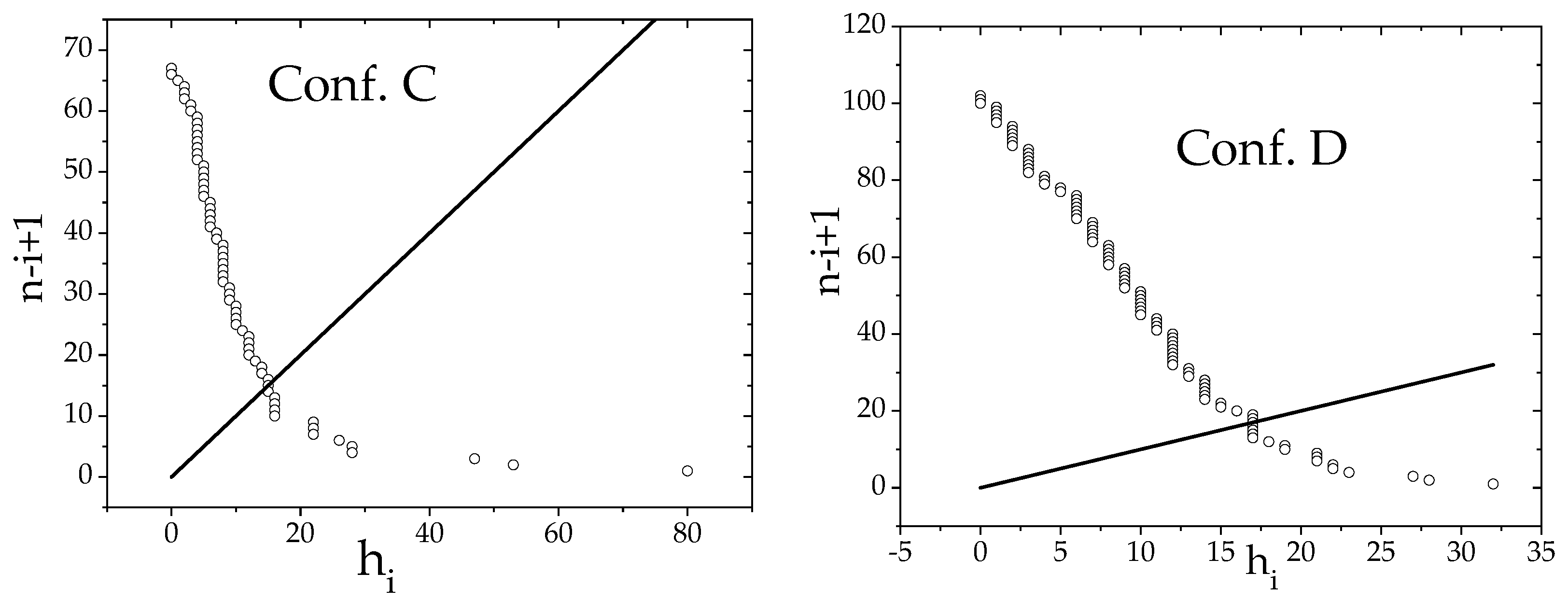

In practice, to find the

it suffices to plot the function

(number of members that have an

h-index higher than

) as a function of

and to determine the intercept between

and the identity function

since

, for

(see

Figure 6).

In the case of groups, a simple procedure is performed:

Input: m groups denoted by , and the number of samples () are required;

For every pair of groups

indexed by

, with

, samples

of

h-indexes of size

are randomly selected from

, with

, and the relative h-group of

with respect to

, i.e.,

, is computed according to Equation (

12).

From that, a ranking for conferences (or groups) can be established based on their relative

and the Gini coefficient. Our main proposed function, the

α-index, is employed to measure the quality of a group

l among

m groups. Equation (

13) defines the

α-index.

where

and

is the Gini coefficient of group

l. The value

measures the quality of a group based on a convenient definition of the

h-index for groups weighed by the Gini coefficient of members in all groups considered for ranking. The factor

works as an amplifier of the relative

. The smaller the

, the more significant the

.

4. Results–I: Editorial Boards of Conferences

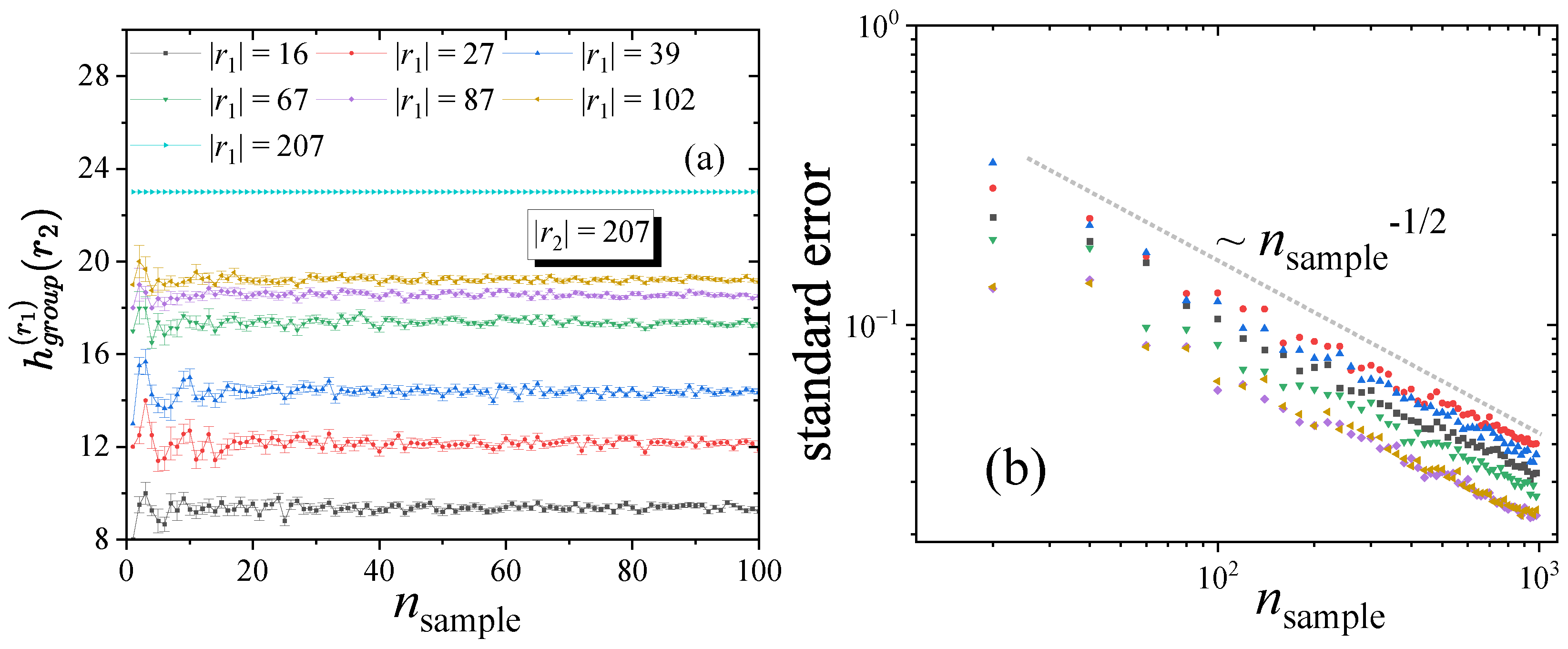

To evaluate the conferences, the first step is to calculate the relative of each conference in relation to the smaller conferences. The smallest program committee (Conf. G) has 16 members, while the largest (Conf. A) has 207 members.

For this calculation, we used the simple algorithm described in

Section 3, with

, which is more than sufficient. Before proceeding, let us illustrate this point by computing

for the largest group size,

, and for all smaller group sizes

and 207.

To do so, we vary

. We observe that

stabilizes rapidly, with noticeable fluctuations only for small values of

, as shown in

Figure 7a. Note that the error bars are very small, of order

, and the standard deviation remains below 1 for

. We also plot the standard error of the mean (often referred to simply as the standard error), which is used to represent the error bars (rather than the standard deviation), as a function of

. As expected, it decreases proportionally to

; see

Figure 7b.

Table 3 presents our proposed ranking of the conferences according to the

α-index. The table also shows the average

h-index of the members of each conference. The

values reported in this table correspond to

, i.e., computed using the entire population of members in each conference, representing the maximum

.

Our results show a divergent ranking from the one that would be established by the simple calculation of the average of the h-indexes. Our α-index shows the need for the inclusion of the Gini coefficient or another homogeneity parameter in the analysis of the quality of conferences. Many conferences have a high due to just a small fraction of the TPC. The Gini coefficient shows how representative the computed is. A low g denotes that the conference has a robust . Furthermore, it means that any smaller sample collected from the group should have the same , making it independent from the sample. Conferences with a high Gini coefficient have discrepant TPC members, which is a sign of questionable quality.

The ranking of conferences according to the α-index differs from the ranking by CAPES, the research funding agency, in two cases. Conf. F is given a lower ranking according to the α-index. In fact, in a later assessment, CAPES re-evaluated subsequent editions of this conference, placing it at a lower rank. The second discrepancy was for Conf. B, which ranked higher according to the α-index. CAPES uses a minimum number of editions as an attribute to determine the quality of the conferences, and this may have led to the incorrect ranking of Conf. B. Our approach does not depend on the number of editions as it analyzes the h-index distribution for a specific edition of a conference, and this is one of its main advantages.

Another characteristic of the α-index is that the relative ordering of the groups would remain the same if only a subset of the conferences had been compared. Furthermore, if we do pairwise comparisons, for example, between conference X and Y, and find that X is better than Y, then comparing Y to Z, we find that Y is better than Z. By transitivity, a comparison between X and Z would result in X having a higher α-index than Z.

The key question here concerns whether this ranking could replace the classification established by the Brazilian agency CAPES for conferences. To address this, we calculated the Spearman correlation coefficient

, which measures the monotonic relationship between two variables; the Kendall coefficient (

), a non-parametric alternative suitable for small samples and ties; and finally, the Kruskal–Wallis test, another non-parametric approach, to evaluate the relationship between the

-index and the assigned quality levels: 3 for A-type conferences, 2 for B-type, and 1 for C-type. For comparison, we also computed the same correlations using the simple average

. The results are summarized in

Table 4.

These results corroborate that the -index provides a better assessment, as it exhibits higher correlations and smaller p-values in the Kruskal–Wallis test. It is important to emphasize that the index is not intended to exactly reproduce the classification trends established by CAPES, but rather to highlight possible distortions in the current system, which may not fully account for group homogeneity and the relative average h-group. In other words, the goal is to propose a pragmatic alternative to replace subjective criteria that may compromise the evaluation process. This consideration is essential to ensure that larger groups are not privileged to the detriment of smaller but higher-quality ones.

Finally, other interesting instances for our approach could be easily experimented. For example, one could consider not only the h-index of the TPC members but also the h-indexes of the authors who have published papers in the conference. The difficulty here is the greater quantity of data required and its pre-processing. In the following section we show results for postgradute programs as an alternative validation of the methodology.

5. Results—II: Additional Validation Through Postgraduate Programs

To test our methodology in a different context, we also collected data from members of several postgraduate programs in Physics in Brazil. As in the case of conferences, the data refer to an earlier period (accessed in 2010) in the Google Scholar service (

http://scholar.google.com), well before the COVID-19 pandemic, thereby avoiding any suggestion of bias. The sample includes nine postgraduate programs. According to CAPES’s classification, levels 7 and 6 correspond to excellent programs, level 5 corresponds to good programs, and levels 4 and 3 are considered regular. For confidentiality reasons, we do not disclose the names of the programs or the exact year of data collection. As in the previous analysis, the data source was Google Scholar.

Table 5 summarizes the data corresponding to the postgraduate programs. Unlike the case of conference editorial boards, here we computed all values of

for

in each program. The values in bold indicate the maximum

for each group

, corresponding, respectively, to programs P1, P2, …, P9. Each column contains the set of values

for

, while the last row shows the average

, which is later used to compute the

-index according to Equation (

13).

The table contains several pieces of information—the number in parentheses after each program denotes its CAPES level (4, 5, 6, or 7). The three rightmost columns show, respectively, the number of members in each program, the corresponding Gini coefficient (also used in the computation of the -index), and finally the value of the -index itself.

We calculated the Spearman and Kendall correlation coefficients between the CAPES level of each program and our -index. These tests yielded and , with very low p-values of and , respectively. The Kruskal–Wallis test provided consistent results, with a statistic of and .

The good correlations suggest that CAPES’s classification captures the general structure of program quality; however, some aspects deserve further attention, particularly when comparing smaller programs to larger ones. Our metric indicates that such evaluations could be improved by incorporating additional quantitative details—such as group homogeneity and representative sampling—in order not to exclude smaller programs, while simultaneously avoiding penalizing larger ones, provided these are not composed mainly of a few ”hot” researchers surrounded by many less productive members.

6. Summary and Conclusions

This paper proposes a new method for classifying research groups across any scientific field. To motivate the approach, we begin with a preliminary pedagogical analysis that describes in detail the statistical properties of groups of researchers, establishing some universal bibliometric stylized facts based on the program committees of scientific conferences.

Next, we formally introduce a quantity that combines the concepts of homogeneity (via the Gini coefficient) and magnitude (through the relative ), which we call the –index. By analyzing both normal and non-normal groups of researchers, we establish a ranking for the seven conferences examined.

When applied to the CAPES classification scheme, our method reveals a strong statistical correlation, indicating that a fair assessment should rely on more than a high average h-index. Features such as group homogeneity, together with a reasonable average h-index, should also be incorporated as criteria to achieve a more balanced and conceptually sound evaluation.

Our conclusions were supported by correlation tests using Spearman, Kendall, and Kruskal–Wallis statistics. Although the correlations are high, it is important to emphasize that our work is primarily recommendatory, illustrating that additional refinements are needed to improve comparisons between smaller and larger groups.

To further demonstrate the versatility of the –index, we also applied it to classify nine postgraduate programs in Physics in Brazil, finding strong agreement with the classification established by CAPES. In this second analysis, the same statistical tests previously applied to the conferences yielded extremely low p-values, providing additional evidence for the robustness of our ranking methodology.

It is important to note that the definition of the group h–index (simply ), used in the construction of the –index, relies first on the concept of the relative . This quantity corresponds to the that a larger group would have if it were reduced to the size of the smaller group. An average over all smaller groups, as well as over its own size, is then considered. This approach captures the superiority of a larger group only when it is truly a well-composed program, without disproportionately favoring group size.

It also deserves further investigation, since the method should be applied to characterize the quality of groups of scientists using other databases, such as ISI–JCR (

Garfield, 2009). In particular, we should ask whether one should expect systematic differences or distortions when different databases are considered.

Naturally, some criticisms and warnings must be raised here. Although Google Scholar offers broad coverage—including regional journals, multiple languages, and diverse document types—its use in bibliometric analyses demands caution. Its coverage may fluctuate over time, with documents occasionally disappearing from the index, thus affecting the reproducibility of citation counts (

Martín-Martín & Delgado López-Cózar, 2021). Moreover, the lack of transparent indexing criteria, heterogeneous metadata quality, and the presence of duplicate or inconsistently parsed records introduce noise into the dataset (

Halevi et al., 2017). The limited search interface—with restrictions on query complexity and filtering—also reduces the ability to replicate searches precisely (

Haddaway et al., 2015). For these reasons, metrics derived from Google Scholar should be interpreted with caution and, whenever possible, cross-checked with more controlled databases such as Web of Science or Scopus (

Martín-Martín et al., 2018).

Despite these criticisms, we note that some studies suggest that the

h-index follows a universal distribution (

da Silva et al., 2012), independent of the database used. The main hypothesis of the present study is that, regardless of the database, such distortions appear to be “democratically” distributed, and cross-database comparisons tend to reflect primarily a scale effect, often yielding similar rankings within the same source.