Abstract

China’s retraction crisis has raised concerns about research integrity and accountability within its scientific community and beyond. To address this issue, we proposed in an earlier publication that Chinese research funders incorporate retraction records into the evaluation of research funding applications by establishing a retraction-based review system. This review system would debar researchers with retraction records from applying for funding for a specified period. However, our earlier proposal lacked practical guidance on how to operationalize such a review system. In this article, we expand on our proposal by fleshing out the proposed ten debarment determinants and offering a framework for quantifying the duration of funding ineligibility. Additionally, we outline the critical steps for implementing the retraction-based review system, address the major challenges to its effective and sustainable adoption, and propose viable solutions to these challenges. Finally, we discuss the benefits of implementing the review system, emphasizing its potential to strengthen research integrity and foster a culture of accountability in the Chinese academic community.

1. Introduction

Amid China’s ongoing retraction crisis, we have proposed a set of five initiatives aimed at addressing the country’s pervasive research integrity issues in a commentary published in Nature Human Behaviour (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2025a). One of these initiatives is to establish a research funding review system that disqualifies individual researchers with retraction records (hereafter “retraction-afflicted researchers”) from applying for research funding. However, we did not elaborate on several critical aspects of the proposed retraction-based review system, including justifications for its necessity, rationales for and operationalization of the ten debarment determinants, implementation of the review system, potential challenges to its implementation, and possible solutions to these challenges. This article addresses these gaps by transforming the proposed retraction-based review system from a conceptual framework into a practical, implementable solution.

This section is divided into four parts to provide a cohesive and detailed background for this study. The first part establishes the necessity of adopting a punitive approach to addressing breaches of research integrity, while also examining the limitations of current practices. The second part emphasizes why research funders are well-positioned to lead efforts to safeguard research integrity through sanctions. The third part focuses on China’s urgent need to implement an upgraded and refined punitive approach, highlighting the challenges that Chinese research funders face in enforcing such measures. Finally, the fourth part introduces the rationales for the ten debarment determinants and explains how they can be operationalized.

1.1. Challenges in Addressing Research Integrity Issues

The retraction guidelines proposed by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) frame retraction primarily as a mechanism for correcting the scientific literature rather than as a means of penalizing misbehaving researchers (COPE Council, 2019). This non-punitive approach is likely intended to foster a shame-free environment that encourages prompt correction of the literature, especially in cases of honest error or self-retraction (Barbour et al., 2017; Fanelli, 2016; Teixeira da Silva & Al-Khatib, 2019; Vuong, 2020a). Similarly, research institutions are expected to “empower scientists to maintain the principles and standards of responsible research practice” rather than adopting a policing role over their conduct (Bouter, 2018b, para. 3). However, the effectiveness of institutional and individual self-regulation in addressing research integrity issues has been increasingly scrutinized and called into question. For instance, the number of institutional investigations reported to the Office of Research Integrity (ORI) remained notably low (Titus et al., 2008), and scientific fraud has become a rapidly growing industry (Richardson et al., 2025). Similarly, self-reported problematic publications and proactive requests for retraction are few and far between (Jin & Yuan, 2023; S. B. Xu & Hu, 2024), suggesting a lack of voluntary accountability among researchers and institutions.

Self-regulation, often considered a lenient approach, is unlikely to work for repeat offenders who breach research integrity knowingly and unscrupulously. Frequently involved in high-profile cases (Coudert, 2019; Retraction Watch, n.d.-c), repeat offenders typically engage in research misconduct (Lei & Zhang, 2018; Mongeon & Larivière, 2016) and account for a large number of retractions (Grieneisen & Zhang, 2012; Pantziarka & Meheus, 2019). Kuroki and Ukawa (2018) estimated that 3–5% of one-time offenders are likely to author another retracted publication within five years of their last retraction, compared to 26–37% of repeat offenders with five retractions. As argued by Sade (2016, p. 661), “until culture change is enacted, the application of sanctions serves as a deterrent to future misconduct”. Therefore, we concur with many scholars (e.g., Dal-Ré et al., 2020; Davis & Berry, 2018; Faria, 2018; Foo & Tan, 2014; Hadjiargyrou, 2015; Kornfeld & Titus, 2017; Pickett & Roche, 2018; Redman & Caplan, 2015) about the need to take a punitive approach actively and widely to curb breaches of research integrity.

Breaches of research integrity that result in retractions often incur extensive adverse consequences for authors of retracted publications. These consequences can be both professional and personal, including reduced citations to their unaffected work (Azoulay et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2013), revocation of academic degrees (e.g., Lieb, 2004), dismissal from positions (e.g., McCook, 2016), publishing bans (Springer, n.d.), and retraction stigma (Teixeira da Silva & Al-Khatib, 2019; S. B. Xu & Hu, 2024). In China, the repercussions can extend beyond academia, with accountable researchers potentially facing sanctions related to employment, loans, and business opportunities (Cyranoski, 2018). These wide-ranging adverse consequences show that a punitive approach is an option for retraction stakeholders to handle breaches of research integrity. However, the punitive approach does not appear to be as effective as anticipated, as indicated by the increase in both the retraction rate (van Noorden, 2023) and the number of retracted publications documented in the Retraction Watch Database (RWDB). Furthermore, it is estimated that many more retractable publications have not been retracted (Ben-Yehuda & Oliver-Lumerman, 2017; Castillo, 2014; Fanelli, 2009; Oransky, 2022b; Xie et al., 2021).

A major contributor to this concerning situation is the frequent inaction of key institutional stakeholders. As revealed by our analysis of 1000 retraction notices (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2024), institutional stakeholders, such as journal authorities (i.e., journal editors and publishers), research institutions, and governing bodies of research integrity, penalize misbehaving researchers only occasionally and/or with minimal severity. They appear reluctant to handle breaches of research integrity, partly due to the tremendous time and resources required for pre-retraction investigations (COPE Council, 2020; Gammon & Franzini, 2013; Michalek et al., 2010) and potential litigation from the authors of retracted publications (COPE Council, 2019; Resnik et al., 2009). Moreover, frequent punitive actions for retractions may attract publicity and, consequently, harm the reputation of institutional stakeholders (Oransky, 2022b), as this may imply sloppiness or incompetence in safeguarding research integrity. Despite the various constraints faced by institutional stakeholders, research funders should and can play a more active role in safeguarding research integrity (Bouter, 2018a; L. Tang, 2022).

1.2. The Leading Role of Research Funders in Safeguarding Research Integrity

In light of increasing research integrity issues, we propose that research funders take the lead in implementing a punitive approach. We present three key reasons to support this stance. First, research funders are obligated to maximize the impact of their research funding. Unfortunately, a tremendous amount of research funding has been squandered on retracted research and publications. For instance, between 1992 and 2012, misconduct-related retractions accounted for approximately USD 58 million (less than 1% of the total) in direct funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, and breaches of research integrity also entailed additional financial costs (Stern et al., 2014). These figures do not include funded research that is retractable but has not been retracted. By adopting a punitive approach, research funders can mitigate the financial losses associated with breaches of research integrity and enhance the return of their funding. Second, the competitiveness of research funds at all levels (Höylä et al., 2016; Tijdink et al., 2016) necessitates punitive measures for breaches of research integrity to improve fairness and meritocracy in research funding allocation. It is incumbent upon responsible research funders to proactively address this need.

Third, in a survey conducted by the Global Research Council (Fraser et al., 2021), some research funders highlighted the importance of their role in safeguarding research integrity. Research funders “should use their power and influence in the research ecosystem to initiate positive change, leading by example” (Fraser et al., 2021, p. 13), a strategy that “can have a profound impact on the behavior of researchers and their institutions” (Bouter, 2018a, p. 145). Their possession of rare resources puts them in a powerful position of influence, allowing for their retraction-related policies to have a broad impact. Given the importance of research funding to research institutions, these institutions are likely to exercise better oversight over their employees’ research activities. Improved engagement and increased support from research institutions would not only enable journal authorities to retract problematic publications more efficiently but also facilitate more effective handling of research integrity issues by governing bodies of research integrity.

Hesselmann et al. (2017, p. 837) argue that “having a visible system of law enforcement and punishment [i.e., retraction], irrespective of its specifics, is more effective in preventing misconduct than having no system at all”. However, as a form of punishment for researchers who engage in misconduct, retraction alone does not appear to be effective for preventing breaches of research integrity, as indicated by the increasing number of retractions (Oransky, 2022b; van Noorden, 2023). Therefore, it is imperative to consider other forms of punishment. Since most retractions result from severe breaches of research integrity (Barbour et al., 2017; S. B. Xu & Hu, 2022a), research funders should impose penalties on retraction-afflicted researchers, such as debarring them from research funding for a specified period of time (Long et al., 2023; National Science Foundation, 2021; L. Tang et al., 2023). However, Ribeiro et al. (2023b) found that retractions and self-corrections do not significantly impact research funding reviews. To empower China’s fight against research integrity issues, we call for the establishment and adoption of clear criteria for debarring retraction-afflicted researchers from applying for research funding (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2025a).

1.3. China’s Retraction Crisis and Sanctions for Breaches of Research Integrity

China is facing a retraction crisis, as evidenced by its alarming retraction statistics (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2025a). As of February 2025, a total of 30,977 publications with Chinese affiliations had been retracted from international academic journals, accounting for a disproportionate 55.3% of the global total (N = 55,998) documented by the RWDB1. In 2022, China’s international retraction rate reached 0.3% (including conference papers), a concerning figure that surpassed the world average of 0.2% and ranked as the highest globally (van Noorden, 2023). The retraction crisis has continued to intensify, with China contributing 3087 retractions in 2022 (55.6% of the global total), a record-breaking 9801 retractions in 2023 (80.3% of the global total), and 2323 retractions in 2024 (59.0% of the global total). Notably, an analysis of the 2024 Stanford lists of the world’s top 2% scientists reveals a concerning pattern: 8.18% of China-affiliated scientists in the career-long list (874 of 10,687) (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2025b) and 6.66% of those in the single-year list (1809 of 27,165) had authored retracted publications. Small Chinese hospitals and medical universities dominate the global leader board of institutional retraction rates. Approximately 70% of the 136 institutions with a retraction rate above 1% were China-affiliated, and around 60% of those were hospitals or medical universities (van Noorden, 2025).

Between 2009 and 2020, over 60% of retracted China-affiliated articles indexed in the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection received funding support, accounting for more than 40% of all retracted funded research worldwide (L. Tang et al., 2023). Furthermore, of the 3,743,909 articles funded by China’s two primary national research funders—the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and the National Social Science Fund of China (NSSFC)—and published in journals indexed in the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), and the Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI) between 2010 and 2024, a total of 3865 were retracted as of June 2025. This translates to a retraction rate of 10 per 10,000 funded publications. These figures, excluding those associated with China’s other research funders at different levels2, highlight a trend with far-reaching consequences. The high rate of retractions among funded research suggests a significant waste of valuable financial and academic resources, highlighting the need for the NSFC and the NSSFC to strengthen their research integrity oversight by penalizing researchers whose funded publications have been retracted. China’s retraction crisis undermines the credibility of the country’s research community. It also distorts international bibliometric assessments, which rely on publication data to evaluate research impact and productivity. Most critically, the frequency of retractions risks inflicting lasting damage on China’s international academic reputation, potentially undermining global collaboration and trust in its scholarly contributions.

To combat China’s retraction crisis and rebuild trust in its research ecosystem, we argue that China must adopt a more robust and punitive approach to managing its retractions and addressing widespread breaches of research integrity. This strategy draws on the ancient Chinese principles of Mengyao Quke (“taking strong medicine to cure a serious illness”) and Zhongdian Zhiluan (“enforcing strict laws to restore order”), emphasizing the need for decisive action to tackle systemic issues. Furthermore, this approach aligns with the recent commitment by China’s Supreme Court to impose stringent penalties for fraudulent activities in scientific research3, reinforcing the urgency and relevance of a tougher stance on breaches of research integrity that lead to retractions.

However, China’s efforts to ensure research integrity have been hampered by fragmentation and inconsistency. Governing bodies at different levels have issued numerous policy documents (Yang et al., 2020), creating a patchwork of provisions and enforcement mechanisms. This lack of coordination has led to widely disparate policy implementation. A significant step towards standardization was taken in August 2022, when 22 national governing bodies, including major research funders like the NSFC and the NSSFC, jointly released a comprehensive regulatory policy (hereafter “the 2022 national policy”)4. The 2022 national policy standardizes the investigation and sanctioning of research integrity breaches nationwide, outlining 14 administrative sanctions, including debarment from research funding applications. In alignment with this policy, both the NSFC and the NSSFC have adopted funding debarment as a sanction for grant recipients who have violated research integrity standards5. Notably, the NSFC has been particularly proactive, enforcing funding debarment for researchers with retracted NSFC-funded publications and publicizing cases of retraction-related sanctions on its official website to enhance deterrence6. Journal article retractions are one of three primary scenarios that have triggered investigations and sanctions by the NSFC, including grant debarment (L. Tang et al., 2023). While current practices aim to differentiate sanctions for various types of research integrity breaches (Ding et al., 2021; Gao & Zhan, 2024), the implementation and effectiveness of the 2022 national policy, as well as those adopted by the NSFC and the NSSFC, remain to be seen. One important factor impeding effective implementation is the lack of concrete measures for operationalizing differentiated and quantified sanctions on breaches of research integrity.

The 2022 national policy mandates that researchers who have breached research integrity must be debarred from government-funded research activities for a period proportional to the severity of their misconduct. However, the implementation of the policy is undermined by several critical shortcomings. While the policy specifies seven types of research integrity breaches, it also introduces an undefined category labelled “other research integrity breaches”. Similarly, the factors that should be considered in determining the severity of sanctions include an unspecified category labelled “other relevant factors”, further contributing to the policy’s lack of clarity. Even more problematically, the policy provides no concrete guidelines for operationalizing the three determinants of sanction severity: the extent of the breach’s deviation from scientific norms, the magnitude of its adverse impact, and the attitude of the alleged breacher toward the investigation. The policy’s lack of specificity in three key aspects, namely identifying sanctionable breaches of research integrity, determining the factors influencing sanction severity, and operationalizing these factors, risks inconsistent and opaque implementation, particularly with respect to handling retractions. The absence of clear criteria for quantifying debarment durations further jeopardizes fair and consistent sanctioning across cases. Additionally, the current policy for sanctioning breaches of research integrity fails to account for several factors that are unique to retractions. These neglected considerations are elaborated upon in the following section.

1.4. Retraction-Based Research Funding Review System

To address the issues outlined above, we proposed a retraction-based research funding review system for Chinese research funders to incorporate into their evaluations of funding applications (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2025a). However, the proposed retraction-based review system remains purely conceptual and lacks underlying rationales for the ten debarment determinants. Therefore, in this section, we provide justifications for each debarment determinant and describe how they can be operationalized. To ensure clarity, we illustrate these debarment determinants using single-authored retracted publications.

1.4.1. Accountability for the Retraction

Although authors of retracted publications are accountable for most retractions (Barbour et al., 2017; Lei & Zhang, 2018; S. B. Xu & Hu, 2022a), non-author entities, such as journal authorities and third parties, have also been found responsible for a considerable number of retractions (Grieneisen & Zhang, 2012; S. B. Xu & Hu, 2022b). Furthermore, not all authors of retracted co-authored publications are held accountable (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2022a). Following the principle of personal culpability (i.e., no accountability, no publishment) (Kremnitzer & Hörnle, 2013), the retraction-based review system applies to only researchers accountable for retraction.

1.4.2. Tardiness of the Retraction

Tardiness of the retraction refers to how long it took to retract a problematic publication and serves as an indicator of the authors’ promptness in assuming responsibility for correcting the literature. The more quickly a problematic publication is retracted, the less harm it will cause. Tardiness of the retraction can be operationalized as the publication-to-retraction time lag of the retracted publication (hereafter “retraction time lag”). If an article or a retraction notice is published online ahead of print, the online publication date is adopted as its publication or retraction date. If no online publication date is available, the print publication date is adopted. If a retraction follows a two-stage procedure (i.e., retraction and then investigation), as recommended by some scholars (Grey et al., 2024; Thorp, 2022), the publication date of the retraction notice issued at the first stage is adopted as the retraction date.

1.4.3. Contamination of the Literature

The number of citations to a retracted publication is an indicator of the negative impact that the retracted publication has on the literature (Bolland et al., 2022b; Fanelli et al., 2022; Schmidt, 2024; Teixeira da Silva & Bornemann-Cimenti, 2016; van Noorden & Naddaf, 2024; S. B. Xu & Hu, 2024). The more citations a retracted publication has accrued, the greater its contamination of the literature. Since authors of retracted publications are not solely responsible for post-retraction citations (except for self-citations), the number of pre-retraction citations and post-retraction self-citations to a retracted publication is adopted as a proxy of literature contamination.

1.4.4. Severity of the Retraction Reason(s)

According to the principle of proportionality (Edwards, 2018; Staihar, 2015; von Hirsch, 1990), debarment should be differentiated based on the severity of retraction reasons. This is consistent with the ORI’s alignment of its administrative actions with the severity of breaches in research integrity (Long et al., 2023). According to our previous study (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2022a), retraction reasons can be classified into four categories in a descending order of severity, namely blatant misconduct, inappropriate conduct, questionable conduct, and honest error. Retraction reasons that cannot be unambiguously identified can be treated as blatant misconduct to incentivize transparency about the process of retraction. When more than one type of retraction reason is identified for a retraction, every type of retraction reason is counted to quantify debarment, which ensures that the consequences reflect the cumulative severity of the retraction reasons.

1.4.5. Passivity of Retraction

Passivity of retraction refers to the level of proactivity exhibited in the process of retracting a publication. It can be classified into three categories (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2025a): passive retraction (i.e., retraction following whistle-blowing and requested/performed by an entity other than the accountable researcher), semi-proactive retraction (i.e., retraction following whistle-blowing and requested/performed by the accountable researcher), and proactive retraction (i.e., retraction self-initiated by the accountable researcher). Categorizing passivity in the retraction process highlights the varying degrees of responsibility and proactivity demonstrated by researchers in addressing problematic publications. Proactive retractions are considered the most desirable (Haghshenas, 2025; Vuong, 2020a), as they display a strong commitment to research integrity and a willingness to correct the scientific record without external prompting.

1.4.6. Funding Status of the Retracted Publication

If the retracted publication was funded, it is a clear case of abusing research funding. Given the tremendous waste of research funding due to breaches of research integrity (Gao & Zhan, 2024; Stern et al., 2014; L. Tang et al., 2023), penalizing researchers with a retraction record of funded publications can serve as a deterrent against future offenses, sending a clear message that abuse of research funding is intolerable to research funders. It also helps to maintain trust in research funders as proactive gatekeepers of research integrity and to ensure that research funding is used appropriately and effectively.

1.4.7. Journal Prestige of the Retracted Publication

The prestige of the journal where a retracted publication originally appeared should be considered when determining debarment duration. Researchers compete intensely for limited publication slots in reputable journals, and retractions from these journals unfairly deny opportunities to other worthy researchers. For fairness, the severity of punishments should increase with journal prestige. This is particularly crucial in the Chinese academic context, where institutional incentives for publishing in prestigious journals are deeply ingrained (Quan et al., 2017; Shu et al., 2022; S. B. Xu, 2020; S. B. Xu et al., 2021). By considering journal prestige, the sanctioning system can help counterbalance existing perverse incentives for publishing flawed research in respectable venues (Barbour, 2015; Bouter, 2015; Vîiu & Păunescu, 2021). Journals included in the WoS Core Collection’s three flagship indexes, namely SCIE, SSCI, and A&HCI, are recognized as prestigious, and publications in these journals generally receive higher recognition and greater rewards in China (Shao & Shen, 2012), which may have contributed to severe breaches of research integrity (Chen, 2019).

1.4.8. Hiding the Retraction from an Application

Hiding a retraction from an application refers to excluding a retracted publication from the publication list of a funding applicant or concealing the status of a retracted publication on the publication list. Such actions are deceptive behaviors intended to misrepresent research productivity in an attempt to mislead the research funder and gain an undeserved advantage in the competition for research funding. These deceptive behaviors not only reflect a lack of repentance or acknowledgement of research integrity breaches but also constitute a serious violation of fair play. Such misconduct should be penalized to uphold the principles of fairness, transparency, and accountability in allocating research funding.

1.4.9. Hiding the Retraction from Assessment

Chinese research funders typically assess funded research projects at various stages to monitor progress and evaluate outcomes. It is crucial for these assessment processes to consider the validity and reliability of the funded research project being evaluated. Hiding a retraction from assessment refers to including a retracted publication as a valid one for the assessment or excluding the retracted publication from the assessment of the funded research project from which it was derived. By penalizing the concealment of retractions from assessments, research funders can highlight the importance of research integrity, ensure accurate evaluations, and maintain the trust and credibility of the research funding process.

1.4.10. Repeat Offense

Repeat offense refers to a situation in which a researcher is held accountable for more than one retraction or repeatedly conceals a retraction in research funding applications and/or assessments of their funded research projects. Such repeat offenses indicate a pattern of habitual breaches of research integrity and can have serious implications for the integrity of the literature and the fair distribution of research funding. To ensure fairness and maintain the credibility of the research funding and assessment processes, it is reasonable to impose harsher punishment for repeat offenses (Chu et al., 2000; Mungan, 2010, 2014; Roberts, 2008). One approach to achieving this is to reactivate debarment for all previous retractions when a new case of retraction or retraction concealment occurs. This measure serves as a deterrent and increases the adverse consequences of repeat offenses.

2. Implementing the Review System

We developed the retraction-based review system through a purposive review of the literature and a detailed analysis of concepts related to retractions and sanctions for breaches of research integrity. The development of this proposal was inspired by the increasing recognition of retraction data as a valuable tool for correcting the literature, as highlighted in a Nature editorial (Nature, 2025). It was also informed by the growing trend of utilizing retraction data to address research integrity issues and protect the integrity of academic publications. Examples of this trend include integrating the RWDB data into citation management applications (Oransky, 2022a), publicizing retraction data in the Stanford lists of the world’s top 2% scientists (Ioannidis et al., 2025), holding elite researchers accountable for their retractions (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2025b), adopting retraction data as an indicator of institutional research integrity (Meho, 2025), disqualifying researchers with retractions due to misconduct from the Highly Cited Researchers list (Oransky, 2022c), and excluding citations to and from retracted publications from the Journal Citation Report (Quaderi, 2025).

In our earlier work, we offered limited guidance on how to operationalize our proposed framework, leaving the implementation of the retraction-based review system unclear (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2025a). To address this gap, this article provides a detailed explanation of how to translate our conceptual framework into a practical application.

2.1. Applying the Review System to Co-Authored Retractions

The retraction-based review system employs the ten debarment determinants to evaluate the liability associated with a retracted publication. In cases where a co-authored publication is retracted, the review system must also assess the responsibility of individual co-authors. Table 1 illustrates the comprehensive approach of the review system in addressing the accountability and involvement of all individuals associated with a retracted co-authored publication. Six determinants, namely tardiness of the retraction, contamination of the literature, severity of the retraction reason(s), passivity of retraction, funding status of the retracted publication, and journal prestige of the retracted publication, collectively assess various aspects of the retracted publication and their impacts on the literature.

Table 1.

Patterns of repeat offenses involving co-authored retracted publications (CRP).

Two other debarment determinants—hiding the retraction from an application and hiding the retraction from assessment—address the misuse of the retracted publication. Authors who are accountable for a retraction should be penalized both for their responsibility in the retraction and for any misuse of the retracted publication. In contrast, co-authors who are not accountable for the retraction should be penalized only for any misuse of the retracted publication. If individual accountability among co-authors cannot be conclusively determined, all co-authors should be equally subject to the retraction-based review system without discrimination. This approach maximizes deterrence and emphasizes the shared accountability of all contributors to a publication, encouraging greater diligence and integrity in collaborative research efforts. Alternatively, the corresponding author and/or the first author could be identified as primarily accountable, or the contribution statement (if available) in the retracted publication could be used to identify the co-author(s) responsible for the retraction, in alignment with the retraction reason(s) disclosed in the retraction notice.

Repeat offense serves as an additional debarment determinant, identifiable based on accountability for the retraction and/or misuse of the retracted publication. As previously argued, repeat offenses should lead to an accumulation of debarment. Three primary patterns of repeat offenses involving co-authored retracted publications can be observed. The first pattern involves a researcher being accountable for at least two co-authored retracted publications, as exemplified by the first two co-authored retracted publications in Table 1 (i.e., CRP1 + CRP2). The second pattern involves a researcher being accountable for at least one co-authored retracted publication and misuse of at least one co-authored retracted publication for which the researcher is not accountable. This is illustrated by nine combinations of the co-authored retracted publications in Table 1 (i.e., CRP1 + CRP3; CRP1 + CRP4; CRP2 + CRP3; CRP2 + CRP4; CRP1 + CRP3 + CRP4; CRP2 + CRP3 + CRP4; CRP1 + CRP2 + CRP3; CRP1 + CRP2 + CRP4; CRP1 + CRP2 + CRP3 + CRP4). The third pattern involves a researcher who is not accountable for any co-authored retracted publication but is accountable for misusing at least two co-authored retracted publications, as illustrated by the last two co-authored retracted publications in Table 1 (i.e., CRP3 + CRP4).

2.2. Data Sources for the Debarment Determinants

Retraction notices, retracted publications, the RWDB, and institutional investigation reports can serve as primary data sources for calculating the debarment duration for six debarment determinants: accountability for the retraction, tardiness for the retraction, severity of the retraction reason(s), passivity of retraction, funding status of the retracted publication, and repeat offense. Funding information about a retracted publication can be retrieved from its Acknowledgements section. Counts of pre-retraction citations and post-retraction self-citations can be obtained from a freely accessible comprehensive database (e.g., Google Scholar and OpenAlex), ideally from the one that captures the highest number of calculated citations to the retracted publication. Although these recommended databases are appealing due to their public availability as data sources for operationalizing debarment determinants, they raise significant concerns about sustainability, comprehensiveness, reliability, and interoperability. Consequently, implementing an effective review system requires thorough and critical scholarly discussion and technical analysis to determine the most suitable data sources.

As for journal prestige, retracted publications can be divided into two categories: those published in journals indexed by the SCIE, the SSCI, and the A&HCI, and those published in journals not indexed by any of these three reputable databases. Although the number of retractions from China’s domestic journals is limited (H. Xu, 2023), it is essential to include these domestic retractions in the review system to ensure a holistic assessment of the research integrity and fair sanctions for breaches of research integrity. Documents submitted by researchers for research funding applications and assessments, which are collectively referred to as research funding documents, can be used as a data source to determine whether a retracted publication was concealed.

In the case of discrepancies among the designated data sources, the source resulting in a longer debarment period should be adopted. If a debarment determinant cannot be clearly identified, it is recommended to apply the highest coefficient and constant for that determinant. This promotes transparency in the retraction process and enhances the informativeness of retraction notices.

2.3. Calculating Debarment Duration

Calculating debarment duration for the accountable author involves eight calculated debarment determinants (#2–#9 in Table 2; hereafter “calculated debarment determinants”). In contrast, for an author who is not accountable, it involves only two calculated debarment determinants (#8 and #9). Each of the eight calculated debarment determinants is assessed and contributes to the overall debarment duration. To determine the debarment duration for each calculated debarment determinant, a constant and a coefficient are assigned to each determinant by the research funder. The assigned constant represents the baseline debarment duration, and the coefficient determines the relative weight or significance of the factor. The debarment duration for each calculated debarment determinant is obtained by multiplying the assigned constant of debarment duration by its corresponding coefficient. The constants for the eight calculated debarment determinants (2–9) are measured in days.

Table 2.

Calculating debarment duration (DD) for a researcher with multiple retractions (repeat offenses).

Notably, the eight calculated determinants function in different ways. Determinants 2 and 3 (i.e., tardiness of the retraction and contamination of the literature) do not involve categorization, whereas determinants 6–9 involve a binary (either–or) choice when calculating the debarment duration. Determinant 5 (i.e., passivity of retraction) involves a tripartite classification. Differently, calculating the debarment duration for Determinant 4 (i.e., severity of the retraction reason(s)) may involve cumulative choices if two or more types of retraction reasons contributed to the retraction.

Table 2 presents a hypothetical scenario where a researcher is accountable for the retractions of three co-authored publications and is responsible for misusing one co-authored retracted publication for which the researcher is not accountable. In this case, the total debarment duration for the researcher with a record of four co-authored retracted publications is calculated as the sum of the individual debarment durations for each of the four retracted publications (i.e., DD1 + DD2 + DD3 + DD4, where DD1 = C2-1 + C3-1 × 30 + C4 + C4/2 + C5 + C6 + C7 + C8 + C9; DD2 = C2-2 + C3-2 × 30 + C4/2 + C4/4 + C5/2 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0; DD3 = C2-3 + C3-3 × 30 + C4/4 + C4/8 + 0 + C6 + C7 + C8 + C9; DD4 = C8 + C9). This cumulative approach ensures that the debarment duration reflects both accountability for the retractions and the misuse of retracted publications, addressing the full scope of the researcher’s involvement in problematic publications.

2.4. Scope and Implementation of the Review System

Given that COPE introduced retraction as a global practice in November 2009, it might be reasonable to limit the application of the retraction-based review system to retracted publications that were published after 2009. However, to promote the punitive approach to curbing breaches of research integrity, we recommend that the proposed review system be applied retroactively to retractions that occurred prior to its official adoption by research funders. Ideally, to maximize deterrence against future offenses and maintain a consistent approach, it is advisable to extend the review system to all Chinese retractions, regardless of their retraction dates.

The debarment from research funding applications takes effect on the more recent of two dates: the date of a researcher’s most recent retraction or the release date of the researcher’s most recent successful funding application. If a successful funding application is active at the time of debarment, it will be revoked. For instance, if a researcher’s most recent successful funding application was announced on 1 August 2024, and their most recent retraction occurred on 15 September 2024, the debarment would take effect on 15 September 2024. As the successful funding application is still active on that date, it should be revoked as part of the debarment process.

If a research funding application team includes two or more members with a retraction record, the debarment duration will be calculated individually for each of these team members. The debarment duration for the entire team will be extended until the expiration of the longest individual debarment, following the principle of maximizing collective punishment and deterrence.

Future research could explore how to incorporate the proposed retraction-based review system into a comprehensive research funding review system. Such a framework should account for not only retraction-related data but also other forms of researcher misconduct in funding applications, including plagiarized grant proposals, fabricated publications, falsified academic credentials, and practices such as pulling strings with funding reviewers (seeking favoritism through personal connections). These issues are currently under scrutiny by Chinese authorities7 and warrant inclusion in a broader integrity-focused review system. The proposed retraction-based research funding review system can be further expanded by incorporating additional debarment determinants, such as the level of cooperation (or lack thereof) demonstrated by accused funding applicants during integrity investigations. Ideally, a comprehensive review system should consider all relevant sanction factors to quantify the duration of debarment from research funding eligibility.

2.5. Key Actions for Implementation

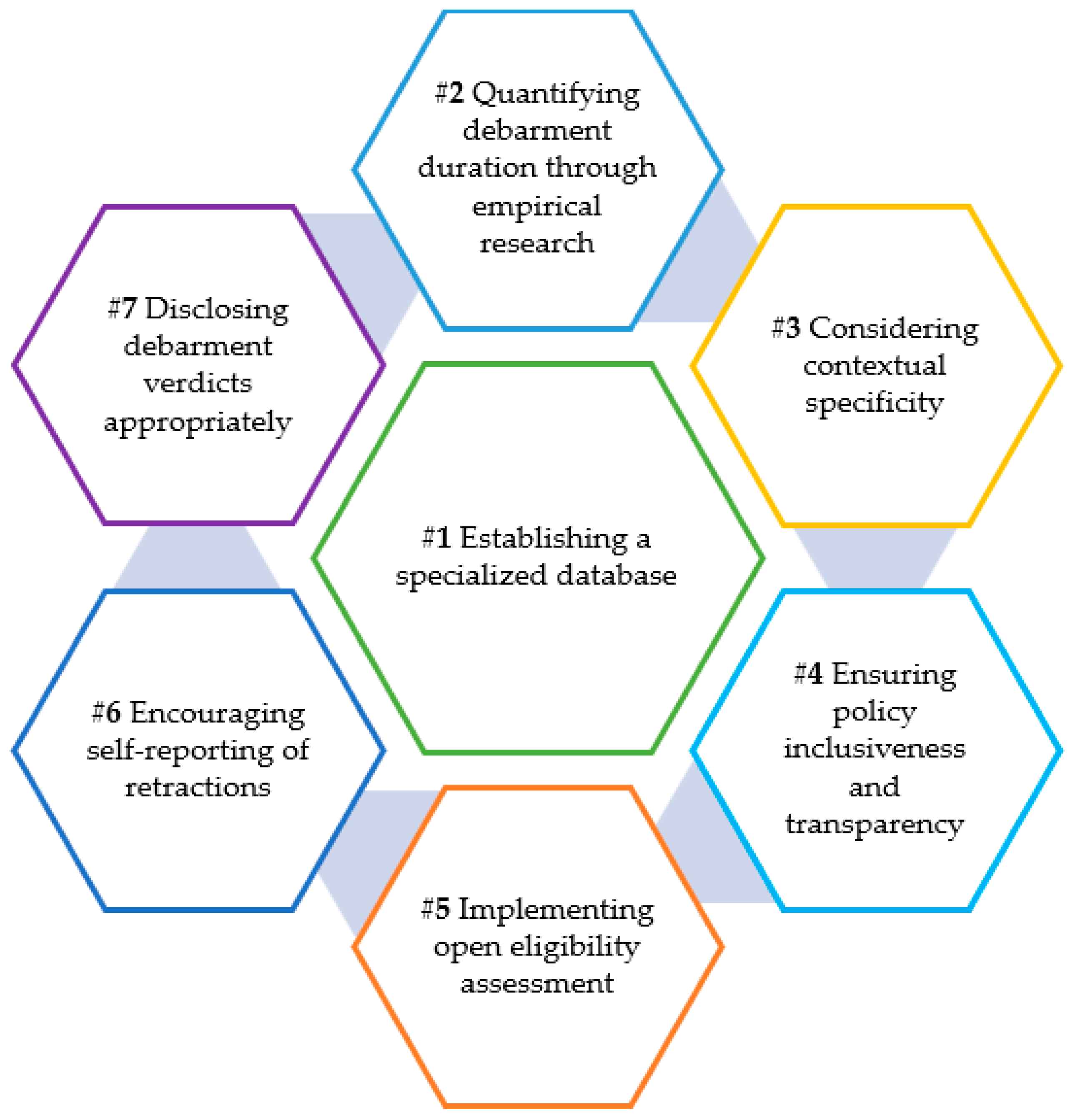

To facilitate the implementation of the proposed retraction-based review system and enhance its feasibility, we recommend seven key actions, as summarized in Figure 1 and detailed in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Seven key actions for implementing the retraction-based review system.

2.5.1. Establishing a Specialized Database

Following our previous suggestion (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2025a), an essential database should be established to lay the groundwork for implementing the retraction-based review system. The database should comprehensively catalogue China-affiliated retractions, with each retracted publication clearly attributed to individual researchers and their affiliated Chinese research institutions. A step toward establishing such a database can be taken by Amend8, a retraction database initiated by the National Science Library at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. It should also include information on funding sources, journal indexation, and data on pre-retraction citations and post-retraction self-citations. Furthermore, the database should include institutional investigation reports, providing a centralized repository for documentation and analysis. This component of the database does not need to be built from scratch. The Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) has already created a database on serious breaches of research integrity, and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences is constructing a similar database for the humanities and social sciences. Building on these existing resources, a dedicated database for retraction-related cases could be developed.

2.5.2. Quantifying Debarment Duration Through Empirical Research

While the retraction-based review system holds great promise, it requires rigorous scholarly discussion and scrutiny before implementation. We recommend two lines of empirical research to inform its development: validating the proposed debarment determinants and determining the constants and coefficients for the eight calculated debarment determinants. Both lines of research should engage a diverse range of stakeholders, including authors of retracted publications, research institutions, research funders, governing bodies of research integrity, research integrity experts, and researchers affected by retractions. Furthermore, given the critical role that research institutions play in implementing the review system, empirical research is needed to identify the difficulties and challenges they may encounter. Findings from such research are expected to offer practical insights for research funders, helping to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of the review system’s implementation.

2.5.3. Considering Contextual Specificity

Research funders should adopt a context-sensitive approach to implementing the review system. Disciplinary differences, for example, should be carefully taken into account. Certain disciplines or research areas may be more susceptible to retractions than others (Grieneisen & Zhang, 2012; Lei & Zhang, 2018; Li & Shen, 2024; S. B. Xu & Hu, 2022a). Retraction susceptibility should be measured by both the number and rate of retractions and should be positively correlated with debarment severity.

To ensure an appropriate level of debarment severity, the constants and coefficients for the eight calculated debarment determinants can be tailored accordingly. Specifically, for each academic discipline, a distinct constant and coefficient should be defined for each of the eight debarment determinants (potentially on an annual basis), and these should be uniformly adopted by all research funders at the national level, such as the NSFC, the NSSFC, the MOST, the Ministry of Education, and the National Health Commission. Considering the downward-tiered pressure escalation observed in the politics of Chinese higher education (Zhang & Wang, 2025), research funders at lower administrative levels are expected to adopt constants and coefficients that are more stringent than those established by their immediate-superior funding authorities.

2.5.4. Ensuring Policy Inclusiveness and Transparency

Research funders should consider the interests and concerns of various key stakeholders and adopt an inclusive approach to policy development and enforcement regarding the review system. First, research funders should actively seek input and feedback from key stakeholders during the policy-making process to gain comprehensive perspectives and ensure that policies reflect diverse needs and concerns. Key stakeholders to be involved should include authors of retracted publications, retraction-free researchers, research institutions, research funders, governing bodies of research integrity, and research integrity experts. It is necessary to engage retraction-afflicted researchers, as they are the targets of the review system and might be willing to offer their perspectives on how to implement the review system.

Furthermore, research funders should make their policies public and accessible before implementation to allow key stakeholders sufficient time to understand and prepare for changes. Research funders should also keep their implemented policies open to continuous refinement, informed by scholarly research, government policies, implementation experiences, and feedback from key stakeholders. Additionally, research funders should strive for transparency in their decision-making processes by providing clear justifications for debarment verdicts and policy changes.

2.5.5. Implementing Open Eligibility Assessment

Research funders should implement a comprehensive system for retraction-based open eligibility assessment of research funding applications. A publicly accessible online debarment calculator, based on a comprehensive database, should be created to facilitate the eligibility assessment. Research funders should require research institutions to assess their employees’ eligibility for research funding applications and issue eligibility reports.

Research funders should publicize the eligibility reports they receive on their web-based databases for a specified period, inviting public scrutiny and feedback to enhance transparency. To minimize workload and increase oversight, higher-level research funders can require that eligibility screening be conducted by research oversight bodies at lower administrative levels. Simultaneously, research funders should perform random verification of eligibility reports from research institutions, especially those with above-average retraction numbers or rates. Research institutions found to have engaged in misconduct related to the issuance of eligibility reports should face penalties from research funders. Such penalties may include imposing restrictions or reducing quotas for research funding applications submitted by the offending research institutions.

2.5.6. Encouraging Self-Reporting of Retractions

Before announcing successful applications, research funders should conduct a final review to determine if any successful applicants have had retractions between the application submission date and the result release date. Any retractions occurring during this period should result in the disqualification of the affected applications. This policy ensures that the most current information on research integrity is considered, maintaining the credibility of the funding review process and encouraging sustained ethical research practices even after submission. To facilitate this process, research funders should require applicants to provide a written commitment to self-report any retractions that occur after submission but before the release of results (i.e., pre-release retractions). Pre-release retractions should result in the nullification of the successful applications if self-reported, or nullification plus permanent research funding debarment if brought to the research funders’ attention by any means other than self-reporting.

To maintain research integrity among successful applicants, a strict policy should be implemented regarding retractions occurring during the funding period. If such retractions are self-reported by the researcher, the unused portion of the research funding should be revoked. However, if retractions are brought to the research funders’ attention through means other than self-reporting, the researcher should face permanent debarment from future research funding, in addition to revocation of the granted funding. The revocation of an ongoing funded research project may unintentionally impact research students who rely on that funding but are not responsible for the retractions. To mitigate this consequence, research institutions should implement a contingency plan, such as transferring affected students to other faculty members and providing interim financial support, to ensure that innocent students are not unduly penalized and can continue their academic pursuits with minimal disruption.

2.5.7. Disclosing Debarment Verdicts Appropriately

Research funders should promptly inform research institutions of debarment verdicts concerning their employees. This timely communication allows the research institutions to take appropriate actions, such as disciplinary and preventive measures, to minimize the risk of future breaches of research integrity. Punishment for retraction-afflicted researchers can be multi-dimensional. Alongside research funders, research institutions and journal authorities should also implement measures, such as publishing bans and demotions. Additionally, these verdicts should be publicly disclosed on official websites in a permanent manner, so as to send a strong message that research funders are committed to upholding research integrity and holding research funding awardees accountable for their misconduct.

Debarment verdicts should identify not only the responsible individuals but also their affiliated research institutions, in line with the provisions outlined in China’s existing policy documents. Furthermore, debarment verdicts should detail reasons for debarment to provide clarity and transparency. Disclosure of detailed reasons for debarment can ensure stakeholders’ clear understanding of the specific breach of research integrity that has led to the debarment. Research funding applicants should have the opportunity to lodge appeals within a specified timeframe after being formally notified by research funders of their ineligibility for research funding applications. It is crucial that research funders handle and conclude these appeals promptly to uphold the due process rights of the affected applicants.

3. Discussion: Challenges and Solutions

Based on the ten debarment determinants and insights from the literature, we have identified eight potential challenges that could impede the effective and sustainable implementation of our proposed retraction-based review system. To address these challenges, we propose targeted solutions. Table 3 summarizes all the challenges and suggested solutions, with detailed elaborations provided in the following sections.

Table 3.

Implementing the retraction-based funding review system: potential challenges and suggested solutions.

3.1. Disregarded Role of Research Funders

The first challenge to implementing the proposed review system is the research funders’ lack of awareness regarding the crucial role that they can and should play in safeguarding research integrity. To address this challenge, research funders are encouraged to collaborate with organizations like the Research Grant Council in promoting responsible research assessment practices. By joining forces, they can collectively raise awareness about the importance of maintaining research integrity.

Importantly, research funders should maintain data records on three research fund debarment determinants (i.e., funding status of the retracted publication, hiding the retraction from an application, and hiding the retraction from assessment), and these data should be shared with research institutions and peer research funders. Data on wasted research funding due to retracted publications can motivate research funders to take a firm stance against research integrity issues and justify their adoption of the review system. Research funders should also recognize that the increasing number of retractions is likely only the tip of an iceberg of retractable publications (Ben-Yehuda & Oliver-Lumerman, 2017; Castillo, 2014; Fanelli, 2009; Oransky, 2022b; Xie et al., 2021). In light of this, research funders should mandate that research institutions conduct or facilitate pre-retraction investigations and communicate the outcomes to journal authorities.

Research funders should also remain fully aware that leniency toward researchers’ retraction records undermines the scientific community’s defense against bad science and unethical publishing. Understanding the severity of this problem can help funders recognize the importance of addressing retractions and the need for a robust system to evaluate research credibility. Including experts in research integrity and retraction on research funders’ administration teams or advisory boards can strengthen policy development and implementation. These experts can provide valuable guidance and insights for handling research integrity issues and implementing the review system. By taking these steps and actively promoting responsible research assessment, research funders can play a crucial role in curbing research integrity issues and ensuring the integrity of their research funding processes.

3.2. Controversy over Imposing Punishment for Honest Error

Many scholars (e.g., Baskin et al., 2017; Enserink, 2017; Fanelli, 2016; Haghshenas, 2025; Oransky, 2022b; Ribeiro et al., 2023a; Teixeira da Silva & Al-Khatib, 2019; Vuong, 2020a) have called for greater recognition of self-retraction and the de-stigmatization of retractions due to honest error. In our proposed review system, self-retraction is acknowledged by setting its debarment duration coefficient to 0. However, honest error is not exempt from debarment. Therefore, the review system may face criticism for penalizing honest error. Nonetheless, based on rational choice theory (Abell, 1991), being lenient toward less serious breaches of research integrity may encourage more serious forms of integrity breaches. Notably, given the punitive nature of the retraction-based review system, honest error is acknowledged by assigning the smallest debarment coefficient. Moreover, imposing punishments for honest error, including debarment from research funding applications, is not uncommon in China. For instance, in a case reported in Science (Normile, 2021), a high-profile Chinese scientist and former president of Nankai University was cleared of misconduct but punished for his honest error of misusing images in multiple research articles.

Admittedly, balancing accountability with the recognition of honest error is a complex task. Accordingly, the review system should be designed with careful consideration of these factors and remain adaptable to new evidence and insights as they emerge. If future empirical data show that honest error leads to more prompt retractions, less serious contamination of the literature, and reduced use of retracted publications in funding applications and assessments of funded research projects, it may be appropriate to consider reducing penalties for honest error or even excluding it from the review system.

3.3. Incomprehensive Researcher-Specific Retraction Records

It may be difficult to obtain a complete retraction record of individual researchers for three reasons. First, publications may be retracted without issuing retraction notices (Teixeira da Silva, 2015). As awareness of how the mechanism of retraction works increases, journal authorities can be expected to stop such a problematic practice, which contravenes the COPE retraction guidelines (COPE Council, 2019) and has been criticized in the literature (Teixeira da Silva, 2015). Journal authorities that have retracted publications without publishing retraction notices are advised to issue informative and transparent retrospective retraction notices.

Second, researchers may intentionally omit retracted publications from their records. This concern results from the observation by Teixeira da Silva et al. (2020) that retractions are rarely disclosed in researchers’ resumes. In response, research funders should require research institutions to include a comprehensive list of publications in the eligibility reports for research funding applicants, explicitly highlighting any retracted publications. As noted earlier, concealing a retraction should result in ineligibility for research funding applications. Research funders should not only conduct a pre-review session to (randomly) verify eligibility reports issued by research institutions but also openly encourage whistle-blowing to deter the concealment of retractions.

Third, retraction-afflicted researchers may have published under different names and affiliations, making it technically challenging and time-consuming to obtain their complete retraction records. Therefore, journal authorities and research funders should mandate the use of ORCIDs in academic publications (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2025c) and integrate retractions into ORCID profiles (Candal-Pedreira et al., 2024). It would also be beneficial if the RWDB standardizes author names for retracted publications (Retraction Watch, n.d.-b).

3.4. Inaccurate Calculation of Retraction Time Lags

Calculating retraction time lags on a daily basis can be challenging for three reasons. First, the publication dates of retraction notices and retracted publications may not always be specified precisely. To address this issue, it is advisable for journal authorities to update retraction notices to provide precise retraction dates. Alternatively, adopting the retraction and publication dates documented by the RWDB is recommended, as they consistently follow a set of date conventions (Retraction Watch, n.d.-a).

Second, retraction notices may overwrite retracted publications, which contravenes the COPE retraction guidelines (COPE Council, 2019). Consequently, publication dates of retracted publications become unknown if they are not disclosed in retraction notices. In such cases, journal authorities are expected to restore access to removed retracted publications and update the corresponding retraction notices accordingly.

Third, there can be delays in issuing retraction notices by journal authorities after a decision to retract has been made. This delay often occurs to align with the release schedule of the nearest issue, resulting in extended retraction time lags. To mitigate this issue, it is suggested that journal authorities, regardless of publishing protocols, publish retraction notices online ahead of print as soon as retraction decisions are made.

3.5. Uninformativeness of Retraction Notices

Effective implementation of the retraction-based review system relies heavily on the transparency and informativeness of retraction notices, particularly regarding three debarment determinants: accountability for the retraction, severity of the retraction reason(s), and passivity of retraction. The lack of transparency and informativeness of retraction notices (Bakker et al., 2024; Grey et al., 2022; Hesselmann & Reinhart, 2021; Shi et al., 2024; Vuong, 2020b) may make it challenging to identify these debarment determinants. This challenge can be further exacerbated if retraction notices are issued promptly upon confirmation of the scientific unreliability of published research, without waiting for the outcome of investigations into the underlying causes, as recommended by some scholars (Grey et al., 2024; Thorp, 2022).

However, calls for improved informativeness and transparency of retraction notices (Teixeira da Silva & Vuong, 2021; Vuong, 2020b), together with robust guidelines on what to communicate in retraction notices (National Information Standards Organization et al., 2024; S. B. Xu & Hu, 2023), are likely to alleviate this difficulty, provided that retraction notice authors, especially journal authorities, respond positively, promptly, and constructively. More importantly, it is advisable for research funders to require research institutions to conduct pre-retraction investigations into alleged publications promptly and communicate their findings transparently to journal authorities (Gunsalus, 2019; Oransky & Marcus, 2025; Schrag et al., 2025). In cases where retraction notices are uninformative due to expedited retractions, follow-up or updated retraction notices should be issued (Teixeira da Silva & Vuong, 2021; S. B. Xu & Hu, 2023).

3.6. Varying Classifications of Retraction Reason Severity

Assessing the severity of retraction reasons as a debarment determinant can be challenging due to the lack of consensus on a severity-based classification system. Unlike the severity-based classification of retraction reasons we proposed (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2022a), which draws on Hall and Martin’s (2019) taxonomy of misconduct, other approaches (e.g., Andersen & Wray, 2019; Azoulay et al., 2015) do not incorporate all three relevant criteria: the invalidity of research data and findings, unethical research and publication behaviors, and the unintentionality of these behaviors. This lack of consensus highlights the need for further academic research and scholarly discussion to achieve a broader agreement on severity-based classifications of retraction reasons. A particular challenge lies in determining intent in breaches of research integrity, which complicates the distinction between honest error and more serious retraction reasons. For instance, we relied on explicit linguistic markers of unintentionality in retraction notices to identify honest error as a retraction reason, which risked misclassifying some instances of de facto honest error as more serious retraction reasons (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2022a).

Given the current situation, it is advisable for research funders to adopt context-specific criteria for classifying retraction reasons based on severity. By considering the unique circumstances of each case, research funders can ensure a more nuanced evaluation of retraction reason severity. This approach acknowledges the complexities involved and allows for a more comprehensive understanding of retraction reasons. Pragmatically, research funders can classify all retraction reasons documented and defined by the RWDB into distinct categories by severity, while incorporating input from experts in law and research integrity. More specifically, the ten indicators of intent in research misconduct proposed by Yeo-Teh and Tang (2024) can be adopted to help distinguish honest error from other retraction reasons. As the academic community continues to engage in ongoing research and discussion, a wider consensus on the severity-based classification of retraction reasons is likely to emerge, leading to more standardized practices and greater clarity in determining debarment duration.

3.7. Misinformation in Retraction Notices and Investigation Reports

A critical concern is the potential manipulation of the retraction-based review system through the disclosure of misleading information in retraction notices and institutional investigation reports. Such manipulation can occur when corrections are used to replace retraction notices in situations where a retraction is warranted due to honest error or problematic practices (Brainard, 2018), and when retraction reasons disclosed in retraction notices appear inconsistent with those identified and publicized by research integrity oversight bodies, often favoring the authors of retracted publications (Yuan et al., 2024). Determining the unintentionality of misbehaviors leading to retractions can be challenging (Abdi et al., 2023; S. B. Xu & Hu, 2022a), raising the possibility that more serious retraction reasons might be concealed as honest error. To address this issue, the framework proposed by Yeo-Teh and Tang (2024) offers a promising approach to establishing intent in cases of research misconduct. If such a framework had been adopted in investigating the allegations of repeated image misuse (Normile, 2021), the former president of Nankai University would likely have been punished for research misconduct rather than (honest) error (i.e., “misuse of images” [图片误用] in 63 papers)9.

Additionally, innocent junior researchers might be scapegoated by culpable senior co-authors and falsely identified as accountable for retraction (Qiu, 2014; B. L. Tang, 2024, 2025). In cases of manipulation, the most viable course of action is to encourage whistle-blowing and impose additional punishment on individuals who engage in such dishonest practices when manipulation is discovered. This approach, which is endorsed by the 2022 national policy, aims to hold those individuals accountable and serve as a deterrent against manipulation of the retraction-based review system.

3.8. Inappropriate Institutional Handling of Retractions

Effective implementation of the retraction-based review system can be undermined by inadequate retraction handling by journal authorities and research institutions. Close cooperation between these institutional stakeholders is crucial for the smooth operation of the retraction mechanism, but unfortunately, such cooperation is not always observed. Research institutions may refuse to investigate allegations that could lead to retractions or may act uncooperatively during investigations initiated by journal authorities (Godlee, 2011; Marcus & Oransky, 2017). Moreover, institutional investigations become financially costly (Gammon & Franzini, 2013; Michalek et al., 2010) and particularly complex (Wager, 2007; Wager et al., 2021), especially in cases involving collaborative research across multiple institutions, either within the same country or internationally (Boesz & Lloyd, 2008; Hesselmann & Reinhart, 2021). Research institutions may hinder the retraction process by failing to communicate their investigation outcomes to journal authorities in a timely and adequate manner (Gunsalus, 2019; Gunsalus et al., 2018; Oransky & Marcus, 2025; Reverman, 2025; Schrag et al., 2025; B. L. Tang, 2024). Journal authorities may ignore or inadequately address credible allegations raised by whistle-blowers (Grey et al., 2019) or fail to respond appropriately to requests for self-retractions due to honest error (Hosseini et al., 2018). There are also instances where journal editors’ insistent requests for retractions are disregarded or disapproved by publishers (Bolland et al., 2022a).

To hold institutional stakeholders accountable for handling retractions adequately and to safeguard their own interests, individual stakeholders, such as the authors of retracted publications and peer researchers who have been victimized or in competition with them, are encouraged to report instances of neglect, nonfeasance, and inadequate handling by institutional stakeholders to web-based research integrity watchdogs, such as Retraction Watch, The Scholarly Kitchen, and PubPeer. These reports may concern alleged breaches of research integrity, requests for retractions, and the execution of retractions. Furthermore, such instances can be documented and incorporated into third-party databases as indicators of post-publication scrutiny responsibility, similar to the “Transparency Index” proposed by the Retraction Watch (n.d.-d) for journals. The Research Integrity Risk Index has been introduced as a comprehensive metric to assess institutional research integrity, based on two measurable outcomes: the rate of retracted publications and the proportion of output in delisted journals (Meho, 2025). These data can be used by journal-indexing services as a criterion for assessing journals and publishers, as well as by major world university rankings to evaluate research institutions.

4. Conclusions

This article seeks to spark a scholarly debate on the role of punitive measures in addressing research integrity issues, with a focus on the potential for research funders to drive a paradigm shift toward a more stringent approach to promoting research integrity. More importantly, we view our proposal (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2025a) of a retraction-based review system as a bold and necessary step forward, particularly in light of China’s ongoing retraction crisis. While our proposal may be perceived as overly ambitious or impractical given the significant challenges discussed above, we argue that it highlights two critical issues: the pervasive reluctance to take genuine responsibility for ensuring research integrity and the lack of effective collaboration among stakeholders in addressing research integrity issues. By pushing the boundaries of conventional thinking, our proposal aims to underscore the urgent need for more effective retraction handling, which requires heightened accountability and resolute collaboration among stakeholders to foster a culture of research integrity.

If Chinese research funders, especially the two primary national ones (i.e., the NSFC and the NSSFC), take the lead in reform by adopting the proposed retraction-based review system, it is expected to catalyze collaboration among stakeholders. Authors of retracted publications who are held accountable will be motivated to promptly and proactively retract their problematic publications to minimize research funding debarment. In contrast, innocent researchers will be incentivized to distinguish themselves from their accountable co-authors and cooperate in pre-retraction investigations to avoid potential debarment. This, in turn, will create a ripple effect: researchers affected by retracted publications or competing for research funding will be motivated to expose breaches of research integrity and hidden retractions. Journal authorities will be expected to adopt responsible and transparent retraction practices, avoid “silent or stealth retraction” (Teixeira da Silva, 2015, p. 5), issue informative retraction notices, update uninformative and opaque retraction notices (e.g., Teixeira da Silva & Vuong, 2021; S. B. Xu & Hu, 2023), and remove paywalls for retraction notices. Furthermore, research institutions will likely exercise more rigorous oversight of research integrity and respond more cooperatively to journal authorities’ requests for investigations into alleged breaches of research integrity, fostering a culture of accountability and transparency.

Optimistically, we envision that effective implementation of the retraction-based review system could have a profound impact on the Chinese research landscape by deterring severe breaches in research integrity, fostering fair competition for research funding, and ensuring consistent accountability for misbehaving researchers. Furthermore, the successful implementation of this review system could expedite the retraction process, mitigate literature contamination, promote transparency in retraction handling, encourage the issuance of informative retraction notices, drive retrospective corrections, and motivate stakeholders to contribute actively to the effective and efficient handling of retractions. Ultimately, we hope that these anticipated positive outcomes will collectively lead to a significant enhancement of research integrity and a marked improvement in the integrity of the Chinese research ecosystem, setting a new standard for research excellence.

Given the prevalence of Chinese retractions in natural sciences10, we expect the NSFC to take the lead in implementing the proposed retraction-based review system, leveraging its expertise and resources to promote research integrity and fairness in allocating its research funding. Ideally, the NSSFC should join the NSFC in implementing the proposed review system. As the two primary national research funders, they are expected to establish the two comprehensive databases mentioned above, which can be shared with each other and other Chinese research funders at different levels. By utilizing China’s top-down approach to research administration (Shu et al., 2022; Zhang & Wang, 2024), successful implementation of the review system by the NSFC and the NSSFC can be effectively promoted to other research funders at various administrative levels.

Our proposed retraction-based review system remains purely theoretical at the current stage. This theoretical focus, while valuable for establishing foundational determinants and principles, lacks validation through data-driven analysis. To address this limitation, we plan to conduct two follow-up empirical studies that will provide proof-of-concept validation and test the feasibility of the proposed review system. The first study will draw on data collected from key stakeholders (e.g., researchers, funders, integrity experts, and integrity officers) to validate the proposed debarment determinants and establish constants and coefficients for the validated ones, ensuring that the parameters of the proposed review system are grounded in expert insights and real-world contexts. The second study will apply these validated determinants, constants, and coefficients to research integrity cases publicized online by the NSFC, offering an empirical test of the review system’s scalability and effectiveness in handling actual retraction data. Given the resources required for these studies, including data collection, analysis, and stakeholder engagement, we welcome research collaboration and intend to seek dedicated research funding to support us.

While our proposal for a retraction-based review system (S. B. Xu & Hu, 2025a) was primarily designed with the Chinese context in mind, reflecting our personal interests and knowledge, we believe that its applicability extends beyond China, potentially through adaptation. This review system could be valuable in any national context where retraction numbers and rates are increasing or exceed the global averages. The principles and mechanisms outlined in this article can be adapted to address similar challenges in research integrity across various countries and academic environments, making it a promising tool for improving research integrity and accountability worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.X. and G.H.; Methodology, S.B.X. and G.H.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, S.B.X.; Writing—Review and Editing, G.H.; Supervision, G.H.; Project Administration, S.B.X.; Funding Acquisition, S.B.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received financial support from Huanggang Normal University through its Scheme of Advanced Incubation Research Projects (202422504) and Think Tank Initiative (202409904).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and academic editor for their constructive feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | All the statistics on retractions presented in this article are derived from data available on the web-based Retraction Watch Database via Crossref (https://gitlab.com/crossref/retraction-watch-data, accessed on 1 September 2025) as of 7 February 2025, unless explicitly indicated otherwise. |

| 2 | In China’s research funding landscape, the National Science Foundation of China and the National Social Science Fund of China are two of the primary national research funders. Alongside these, many other national-level entities also provide research funding, such as the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Ministry of Education, and the National Health Commission. Additionally, many of these national funding bodies have corresponding provincial and local counterparts that support research at regional levels. Furthermore, individual research institutions often allocate internal funding to support their employees’ research activities. |

| 3 | https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202501/07/WS677c7ee8a310f1265a1d9548.html (accessed on 1 September 2025). |

| 4 | https://www.most.gov.cn/xxgk/xinxifenlei/fdzdgknr/fgzc/gfxwj/gfxwj2022/202209/t20220907_182313.html (accessed on 1 September 2025). |

| 5 | https://www.nsfc.gov.cn/publish/portal0/jd/03/info88369.htm and http://www.nopss.gov.cn/n1/2019/0703/c219644-31210616.html (accessed on 1 September 2025). |

| 6 | https://www.nsfc.gov.cn/publish/portal0/jd/04/ (accessed on 1 September 2025). |

| 7 | https://www.nsfc.gov.cn/publish/portal0/tab475/info88329.htm (accessed on 1 September 2025). |

| 8 | https://amend.fenqubiao.com (accessed on 1 September 2025). |

| 9 | https://www.most.gov.cn/tztg/202101/t20210121_172330.html (accessed on 1 September 2025). |

| 10 | As of 31 July 2024, data from the Retraction Watch Database revealed that 70.6% (n = 18,879) of China’s 26,732 retracted publications were in basic life sciences, environment, health sciences, and physical sciences. |

References

- Abdi, S., Nemery, B., & Dierickx, K. (2023). What criteria are used in the investigation of alleged cases of research misconduct? Accountability in Research, 30(2), 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abell, P. (1991). Rational choice theory. Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, L. E., & Wray, K. B. (2019). Detecting errors that result in retractions. Social Studies of Science, 49(6), 942–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay, P., Bonatti, A., & Krieger, J. L. (2017). The career effects of scandal: Evidence from scientific retractions. Research Policy, 46(9), 1552–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]