Cyclic Fatigue Resistance and Phase Transformation Behavior of SlimShaper and SlimShaper PRO NiTi Instruments: A Mechanical and Thermal Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

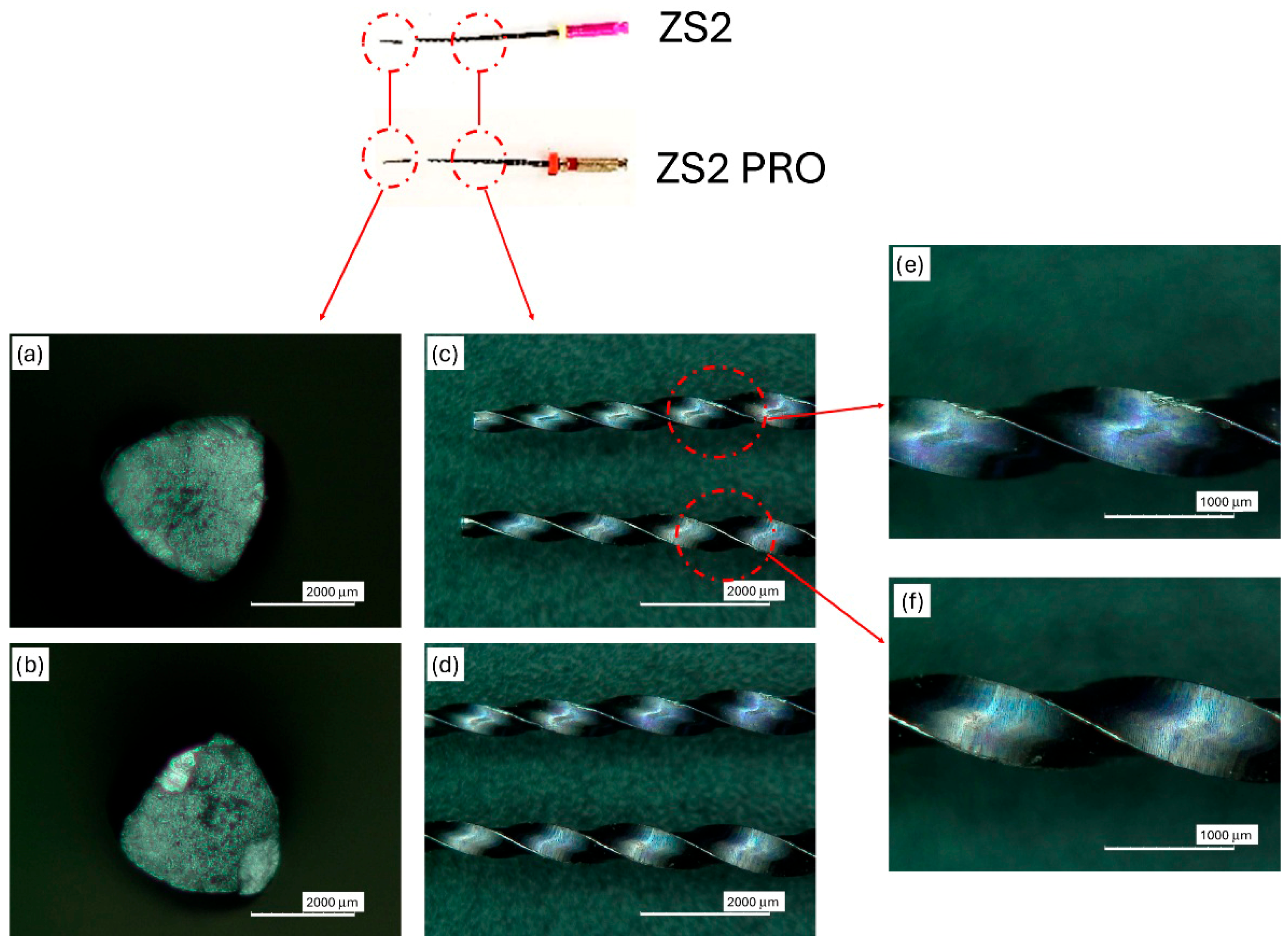

2.1. Geometry of the Endodontic Instruments

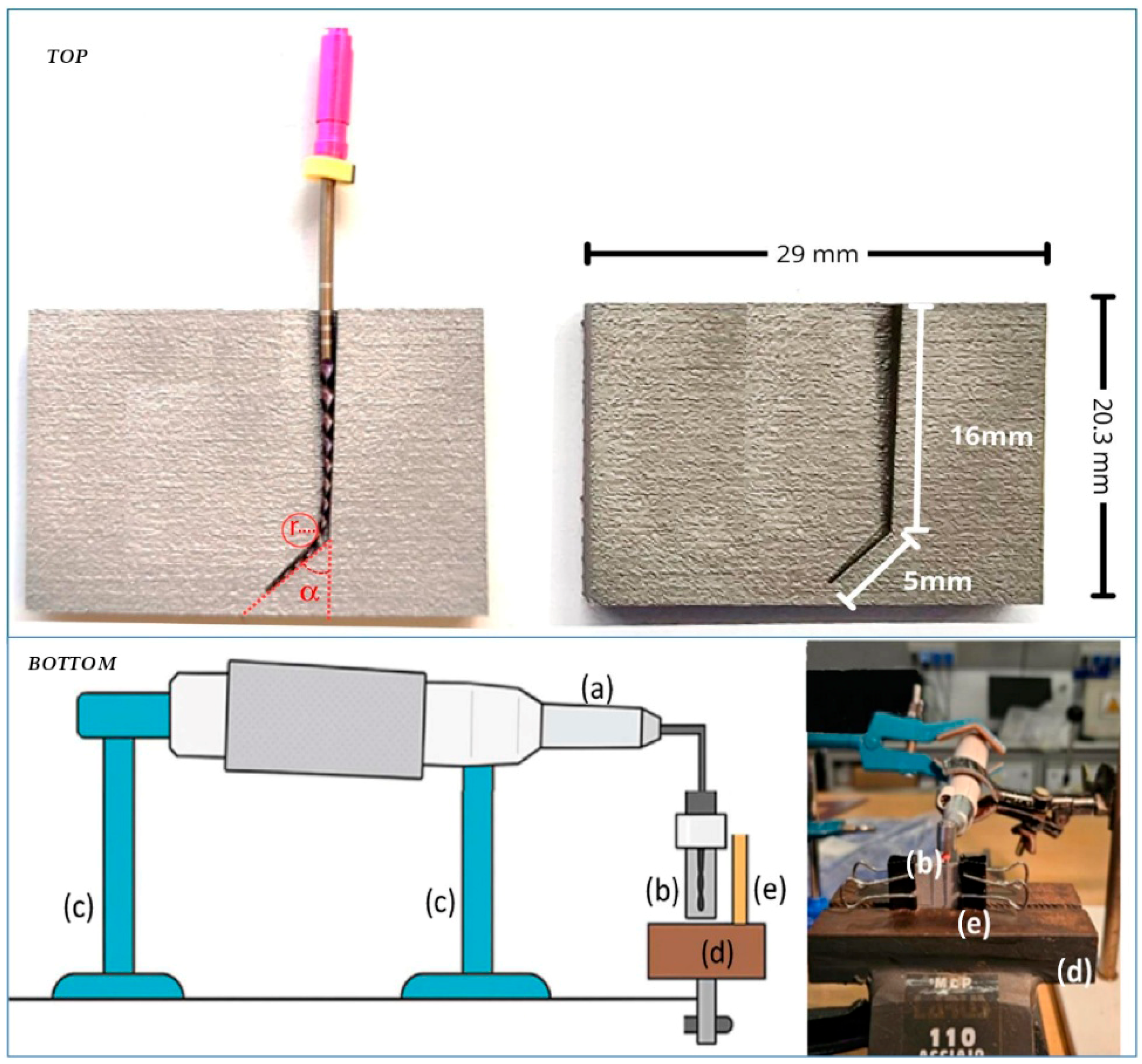

2.2. Fatigue Test

Statistical Analysis

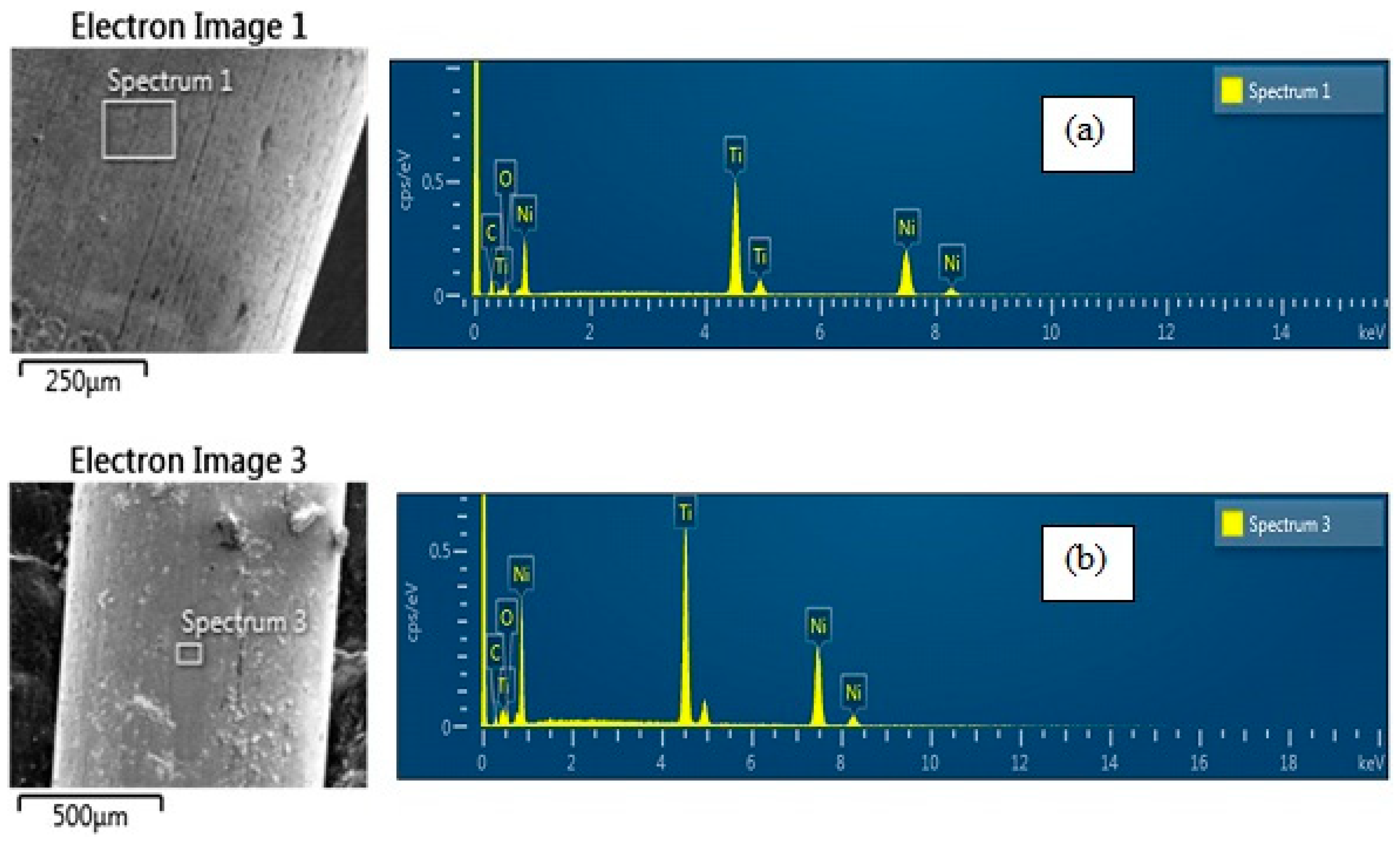

2.3. SEM-EDS Measurements and Optical Microscopy Observations

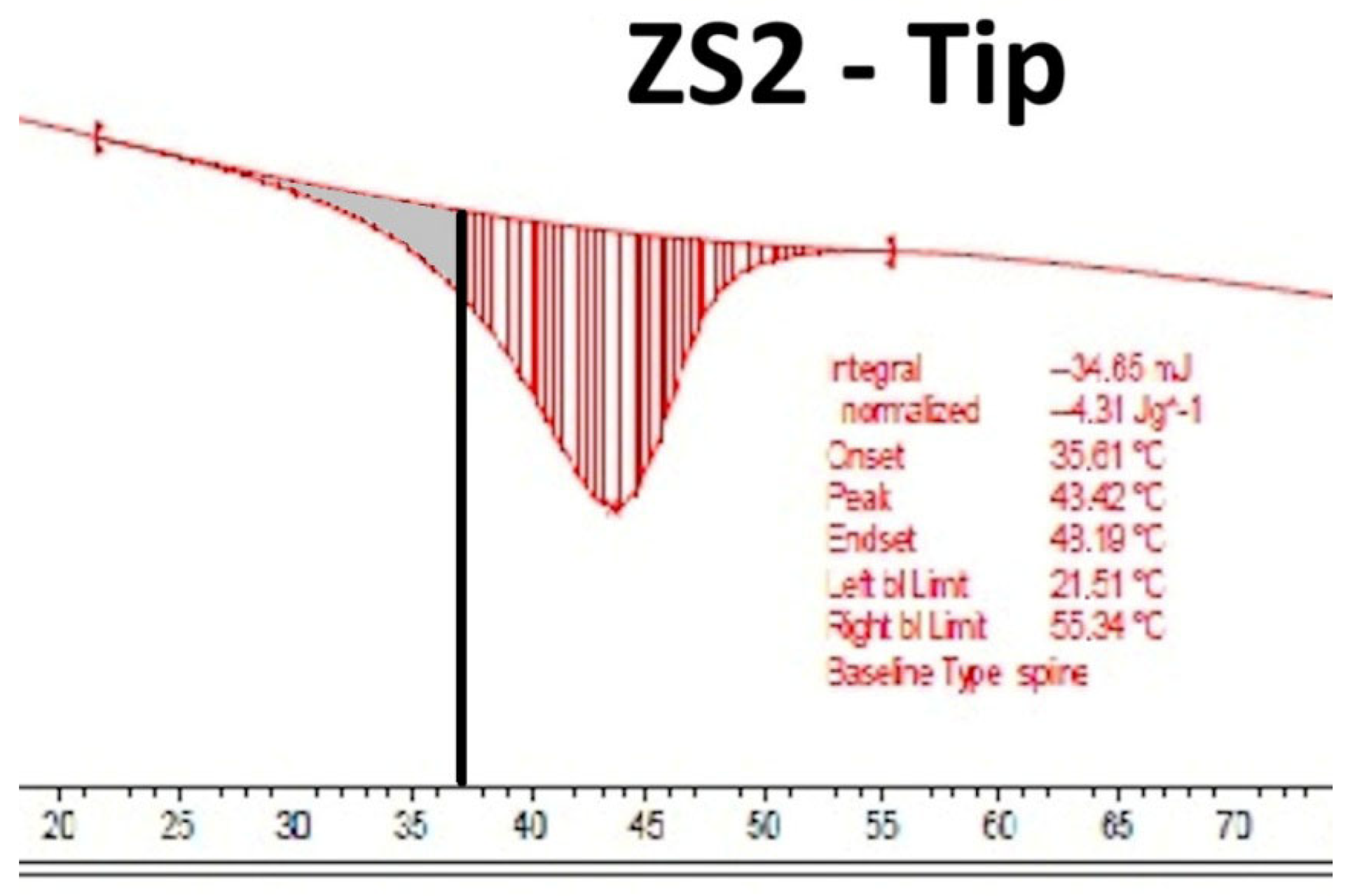

2.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

3. Results

3.1. Fatigue Test

3.2. Morphological Investigation

3.3. SEM-EDS Analysis

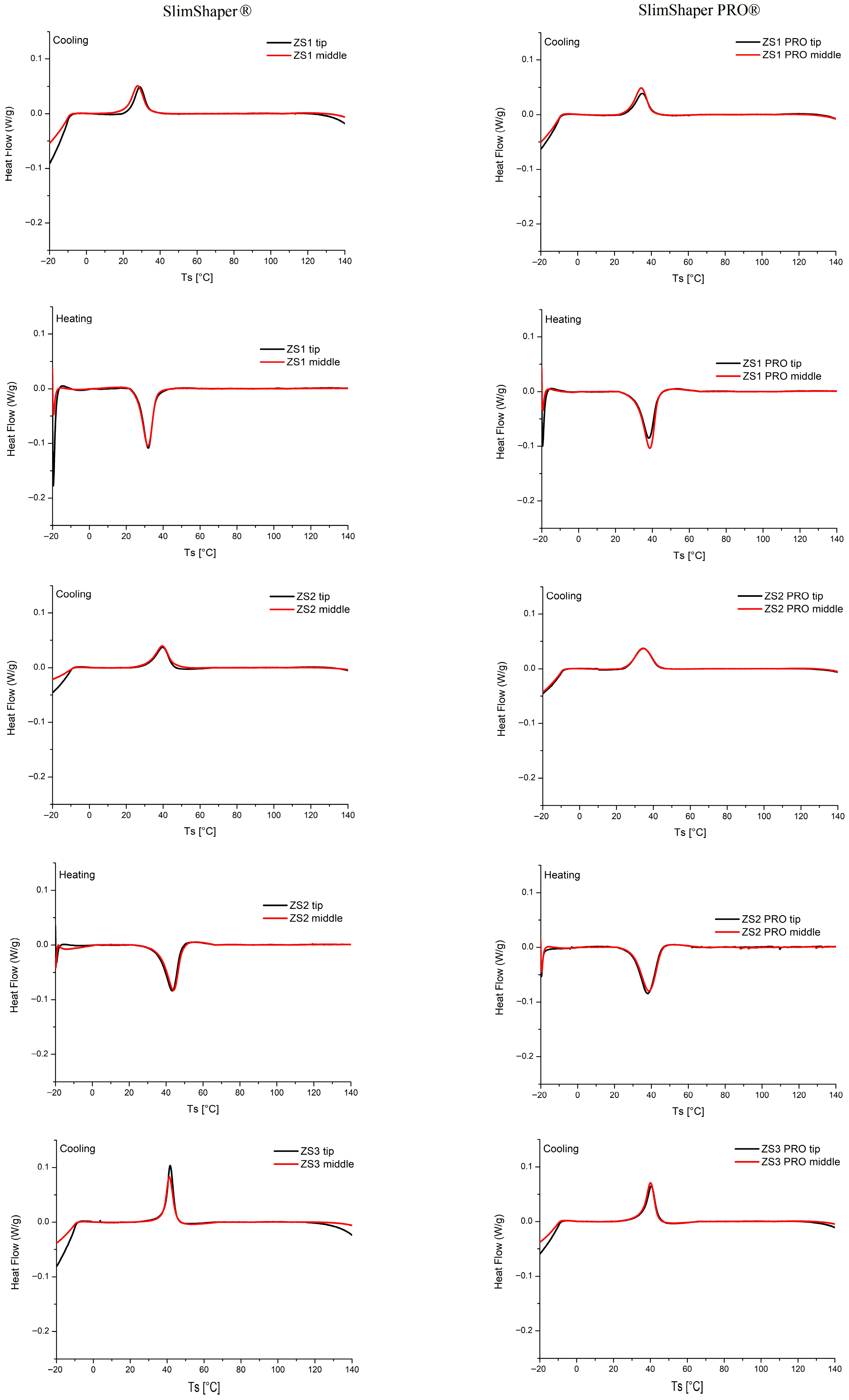

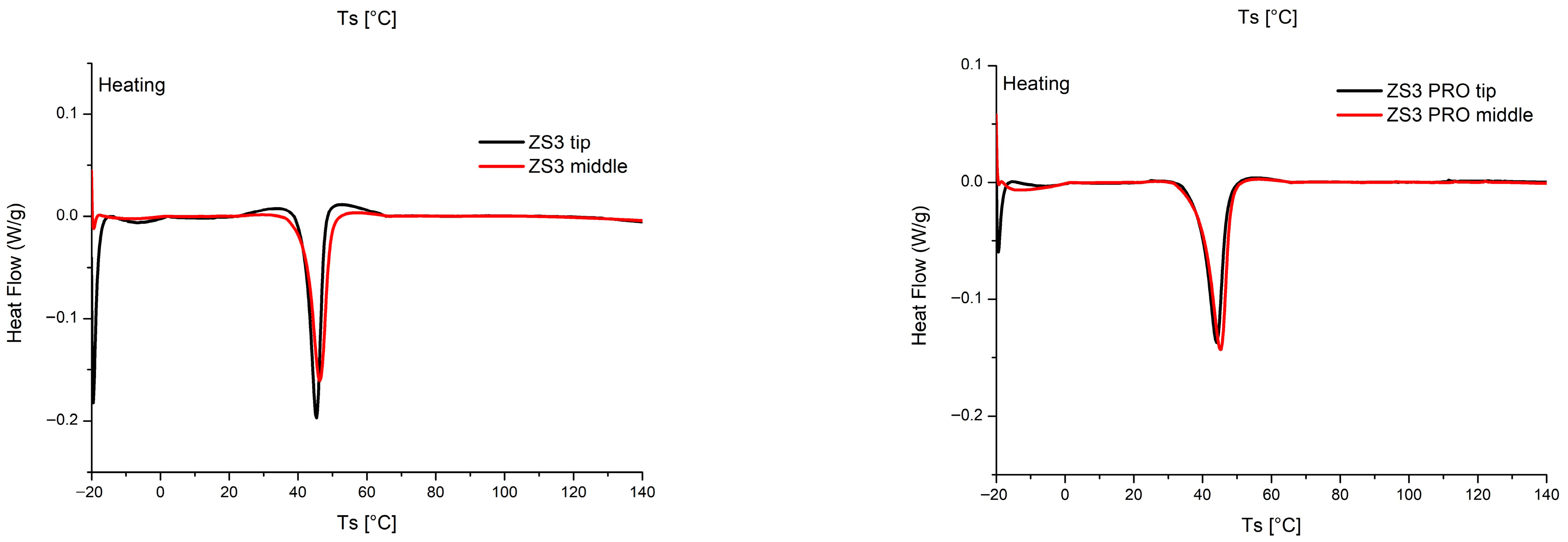

3.4. DSC Analysis

- The normalized peak area, representing the transformation enthalpy, is essentially the same for each part of the endodontic instruments, being in the range between 4 and 5 mJ/g.

- The tip and the middle part of each ZS1, ZS2, ZS3 SlimShaper® and SlimShaper PRO® instrument do not show appreciable differences in the transformation temperatures; therefore, it can be deduced that each instrument, presenting homogeneous characteristics, has not undergone differentiated heat treatments.

- Room temperature (27 °C) is slightly higher than AS (equal to about 26 °C) only for the ZS1 SlimShaper® instrument, which could be partially austenitic. In all other cases AS ≥ 30 °C, excluding the formation of austenite at room temperature.

- Room temperature (27 °C) is higher than MF (equal to about 23 °C) for the ZS1 SlimShaper® instrument and slightly higher than MF (equal to about 26 °C) for the ZS2 SlimShaperPRO® instrument, which could be partially austenitic. In all other cases MF ≥ 27 °C, excluding the formation of austenite at room temperature. This finding indicates that both instruments exhibit homogeneous characteristics along their length and have not undergone differentiated heat treatments. Based on the transformation temperature values reported in Table 2, the microstructures at room temperature can be deduced as summarized in Table 3.

4. Discussion

4.1. Fatigue Test

4.2. Morphological Investigation

4.3. SEM-EDS Analysis

4.4. DSC Analysis

4.5. Clinical Implications

4.6. Limitations

4.7. Strengths of the Study

4.8. Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AS | Austenite Start |

| AF | Austenite Finish |

| MS | Martensite Start |

| MF | Martensite Finish |

| SEM-EDS | Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy |

| OM | optical microscopy |

| NiTi | Nickel–Titanium |

| Mp | Martensitic peak |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

Appendix A

References

- Ovsay, E.; Atav, A.; AlOmari, T.; Bhardwaj, A. Role of temperature on the cyclic fatigue resistance of thermally treated NiTi files. Ann. Stomatol. 2025, 16, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, P.R.; Chandak, M.; Nikhade, P.P.; Patel, A.S.; Bhopatkar, J.K. Revolutionizing endodontics: Advancements in nickel–titanium instrument surfaces. J. Conserv. Dent. Endod. 2024, 27, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Kwak, S.W.; Ha, J.-H.; Sigurdsson, A.; Shen, Y.; Kim, H.-C. Effect of different heat treatments and surface treatments on the mechanical properties of nickel–titanium rotary files. Metals 2023, 13, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghibi, M.S.; Shahmirah, H.; Omidian, S.; Mirzavand-Borujeni, A. Significance of heat treatment on the mechanical and fatigue properties of NiTi endodontic rotary files. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 6497–6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, S.; Zafar, K.; Umer, F. NiTi rotary systems: What’s new? Eur. Endod. J. 2019, 3, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupanc, J.; Vahdat-Pajouh, N.; Schäfer, E. New thermomechanically treated NiTi alloys—A review. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 1088–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotino, G.; Grande, N.M.; Mercadé Bellido, M.; Testarelli, L.; Gambarini, G. Influence of Temperature on Cyclic Fatigue Resistance of ProTaper Gold and ProTaper Universal Rotary Files. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 200–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimoga, G.; Kim, T.-H.; Kim, S.-Y. An intermetallic NiTi-based shape memory coil spring for actuator technologies. Metals 2021, 11, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanza, A.; D’Angelo, M.; Reda, R.; Gambarini, G.; Testarelli, L.; Di Nardo, D. An update on nickel–titanium rotary instruments in endodontics: Mechanical characteristics, testing and future perspectives. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, F.; Cunliffe, J.; Darcey, J. Current technology in endodontic instrumentation: Advances in metallurgy and manufacture. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 231, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.N.R.; Silva, E.J.N.L.; Marques, D.; Ajuz, N.; Rito Pereira, M.; Pereira da Costa, R.; Braz Fernandes, F.M.; Versiani, M.A. Characterization of the file-specific heat-treated ProTaper Ultimate rotary system. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puleio, F.; Tosco, V.; Monterubbianesi, R.; Pirri, R.; Alibrandi, A.; Pulvirenti, D.; Simeone, M. Comparison of four Ni–Ti rotary systems: Dental students’ perceptions in a multi-center simulated study. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çapar, I.D.; Arslan, H. A review of instrumentation kinematics of engine-driven nickel–titanium instruments. Int. Endod. J. 2016, 49, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, E.; Jungbluth, H.; Jepsen, S.; Gruener, M.; Bourauel, C. Comparing cyclic fatigue resistance and free recovery transformation temperature of NiTi endodontic single-file systems using a novel testing setup. Materials 2024, 17, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, J.A.; Mendez, S.P.M.; Malvicini, G.; Grandini, S.; Gaeta, C.; García Guerrero, A.P.; Miranda Robles, K.L.; Aranguren, J.; Pérez, A.R. Multimodal evaluation of three NiTi rotary systems: Clinical simulation, mechanical testing, and finite element analysis. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faus-Matoses, V.; Pérez García, R.; Faus-Llácer, V.; Faus-Matoses, I.; Alonso Ezpeleta, Ó.; Albaladejo Martínez, A.; Zubizarreta-Macho, Á. Comparative study of SEM evaluation, EDX assessment, morphometric analysis, and cyclic fatigue resistance of three novel NiTi alloy files. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puleio, F.; Lo Giudice, G.; Militi, A.; Bellezza, U.; Lo Giudice, R. Does low-taper root canal shaping decrease the risk of root fracture? A systematic review. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puleio, F.; Bellezza, U.; Torre, A.; Giordano, F.; Lo Giudice, G. Apical transportation of apical foramen by different NiTi alloy systems: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, D.; Iandolo, A.; Scorziello, M.; Sangiovanni, G.; Pisano, M. Cyclic fatigue of different Ni–Ti rotary file alloys: A comprehensive review. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahran, S.S. Impact of anatomical and clinical variables on the success of endodontic instrument fragment retrieval. J. Oral Sci. 2025, 67, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alapati, S.B.; Brantley, W.A.; Svec, T.A.; Powers, J.M.; Nusstein, J.M.; Daehn, G.S. SEM observations of nickel–titanium rotary endodontic instruments fractured during clinical use. J. Endod. 2005, 31, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertuğrul, İ.F.; Arslan, H.K. Investigation of four nickel–titanium endodontic instruments with cyclic fatigue resistance, SEM, and EDX. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2024, 87, 2801–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hülsmann, M.; Donnermeyer, D.; Schäfer, E. A critical appraisal of studies on cyclic fatigue resistance of engine-driven endodontic instruments. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 1427–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Coil, J.M.; McLean, A.G.; Hemerling, D.L.; Haapasalo, M. Defects in nickel–titanium instruments after clinical use. Part 5: Single use from endodontic specialty practices. J. Endod. 2009, 35, 1363–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.C.; Bahia, M.G.; Buono, V.T. Surface analysis of ProFile instruments by SEM and EDX: A preliminary study. Int. Endod. J. 2002, 35, 848–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alapati, S.B.; Brantley, W.A.; Iijima, M.; Schricker, S.R.; Nusstein, J.M.; Li, U.M.; Svec, T.A. Micro-XRD and modulated DSC investigation of nickel–titanium rotary instruments. Dent. Mater. 2009, 25, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanza, A.; Seracchiani, M.; Reda, R.; Miccoli, G.; Testarelli, L.; Di Nardo, D. Metallurgical tests in endodontics: A narrative review. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantley, W.A.; Svec, T.A.; Iijima, M.; Powers, J.M.; Grentzer, T.M. Differential scanning calorimetry of NiTi rotary instruments after simulated clinical use. J. Endod. 2002, 28, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, E.J.N.L.; Giraldes, J.F.N.; de Lima, C.O.; Vieira, V.T.L.; Elias, C.N.; Antunes, H.S. Influence of heat treatment on torsional resistance and surface roughness of NiTi instruments. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasuga, Y.; Kimura, S.; Maki, K.; Unno, H.; Omori, S.; Hirano, K.; Ebihara, A.; Okiji, T. Phase transformation and mechanical properties of heat-treated nickel-titanium rotary endodontic instruments at room and body temperatures. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhou, H.M.; Zheng, Y.F.; Peng, B.; Haapasalo, M. Current challenges and concepts of the thermomechanical treatment of nickel-titanium instruments. J. Endod. 2013, 39, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SlimShaper | SlimShaper PRO | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Fracture Time [s] | Mean Number of Cycles Before Fracture | Treatment | Mean Fracture Time [s] | Mean Number of Cycles Before Fracture | Treatment | D [%] | p Value | |

| ZS1 | 102.8 ± 22.39 | 856.6 | Gold | 105.83 ± 16.76 | 881.91 | Gold/Silver | −5.99 | 0.7981 |

| ZS2 | 59.5 ± 16.31 | 495.8 | Pink | 31.00 ± 5.18 | 258.3 | Pink/Gold | 72.86 | 0.0022 |

| ZS3 | 67.0 ± 14.17 | 558.3 | Blue | 39.67 ± 5.47 | 330.58 | Blue/Gold | 64.94 | 0.0013 |

| Cooling (°) | Heating (°) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS [°C] | MF [°C] | Mp [°C] | Peak Area [mJ] | Na [mJ/g] | AS [°C] | AF [°C] | Ap [°C] | Peak Area [mJ] | Na [mJ/g] | |

| ZS1 | ||||||||||

| Tip | 33.49 | 23.79 | 28.95 | 13.21 | 3.22 | 26.23 | 36.14 | 31.93 | 17.64 | 4.30 |

| Middle | 33.18 | 22.33 | 27.70 | 27.8 | 3.49 | 25.62 | 36.27 | 31.58 | 36.65 | 4.60 |

| ZS1 PRO | ||||||||||

| Tip | 40.47 | 28.26 | 35.28 | 20.07 | 3.39 | 31.13 | 43.17 | 38.10 | 24.45 | 4.13 |

| Middle | 39.97 | 27.75 | 34.62 | 39.02 | 4.42 | 31.55 | 43.12 | 38.74 | 41.88 | 4.74 |

| ZS2 | ||||||||||

| Tip | 45.65 | 31.89 | 39.70 | 35.16 | 4.37 | 35.61 | 48.19 | 43.42 | −34.65 | −4.31 |

| Middle | 45.83 | 31.59 | 39.44 | 37.65 | 5.07 | 35.99 | 49.00 | 43.95 | −36.19 | −4.89 |

| ZS2 PRO | ||||||||||

| Tip | 42.11 | 26.39 | 34.35 | 19.54 | 3.94 | 29.94 | 45.17 | 38.12 | −23.50 | −4.74 |

| Middle | 42.45 | 26.13 | 34.70 | 32.64 | 4.06 | 30.06 | 45.67 | 38.76 | −38.49 | −4.79 |

| ZS3 | ||||||||||

| Tip | 44.89 | 38.68 | 41.62 | 21.88 | 5.35 | 41.64 | 47.79 | 45.42 | 24.02 | 5.87 |

| Middle | 45.04 | 37.83 | 41.23 | 62.59 | 4.87 | 41.82 | 49.51 | 46.36 | 70.37 | 5.48 |

| ZS3 PRO | ||||||||||

| Tip | 44.40 | 35.76 | 40.54 | 34.17 | 4.71 | 38.82 | 47.27 | 44.07 | 36.75 | 5.06 |

| Middle | 44.03 | 35.38 | 39.98 | 68.60 | 5.05 | 39.17 | 48.30 | 45.19 | 78.81 | 5.80 |

| Instrument Code | Investigated Part | Microstructures at 27 °C |

|---|---|---|

| ZS1 | Tip | Martensitic/partially austenitic |

| Middle | Martensitic/partially austenitic | |

| ZS1 PRO | Tip | Martensitic |

| Middle | Martensitic | |

| ZS2 | Tip | Martensitic |

| Middle | Martensitic | |

| ZS2 PRO | Tip | Martensitic/partially austenitic |

| Middle | Martensitic/partially austenitic | |

| ZS3 | Tip | Martensitic |

| Middle | Martensitic | |

| ZS3 PRO | Tip | Martensitic |

| Middle | Martensitic |

| Instrument Code | Investigated Part | Total Peak Area [mJ/g] | Area Integrated from AS to 37 °C [mJ/g] | Austenite at 37 °C [%] | Martensite at 37 °C [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZS1 | Tip | 4.30 | 4.30 | 100 | 0 |

| Middle | 4.60 | 4.60 | 100 | 0 | |

| ZS1 PRO | Tip | 4.13 | 1.34 | 32.42 | 67.58 |

| Middle | 4.74 | 2.44 | 51.45 | 48.55 | |

| ZS2 | Tip | 4.31 | 0.80 | 18.52 | 81.48 |

| Middle | 4.89 | 0.60 | 12.18 | 87.82 | |

| ZS2 PRO | Tip | 4.74 | 2.12 | 44.79 | 55.21 |

| Middle | 4.79 | 1.98 | 41.30 | 58.70 | |

| ZS3 | Tip | 5.87 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Middle | 5.48 | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

| ZS3 PRO | Tip | 5.06 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Middle | 5.80 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Scolaro, C.; Puleio, F.; Sili, A.; Visco, A. Cyclic Fatigue Resistance and Phase Transformation Behavior of SlimShaper and SlimShaper PRO NiTi Instruments: A Mechanical and Thermal Analysis. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010022

Scolaro C, Puleio F, Sili A, Visco A. Cyclic Fatigue Resistance and Phase Transformation Behavior of SlimShaper and SlimShaper PRO NiTi Instruments: A Mechanical and Thermal Analysis. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleScolaro, Cristina, Francesco Puleio, Andrea Sili, and Annamaria Visco. 2026. "Cyclic Fatigue Resistance and Phase Transformation Behavior of SlimShaper and SlimShaper PRO NiTi Instruments: A Mechanical and Thermal Analysis" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010022

APA StyleScolaro, C., Puleio, F., Sili, A., & Visco, A. (2026). Cyclic Fatigue Resistance and Phase Transformation Behavior of SlimShaper and SlimShaper PRO NiTi Instruments: A Mechanical and Thermal Analysis. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010022