Patterns of Endodontic Practice and Technological Uptake Across Training Levels in Spain and Latin America: Results from a Multicountry Survey of 1358 Clinicians

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Questionnaire Development

2.3. Survey Distribution

2.4. Sample Validation

2.5. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Magnification and Imaging

3.3. Irrigants and Activation

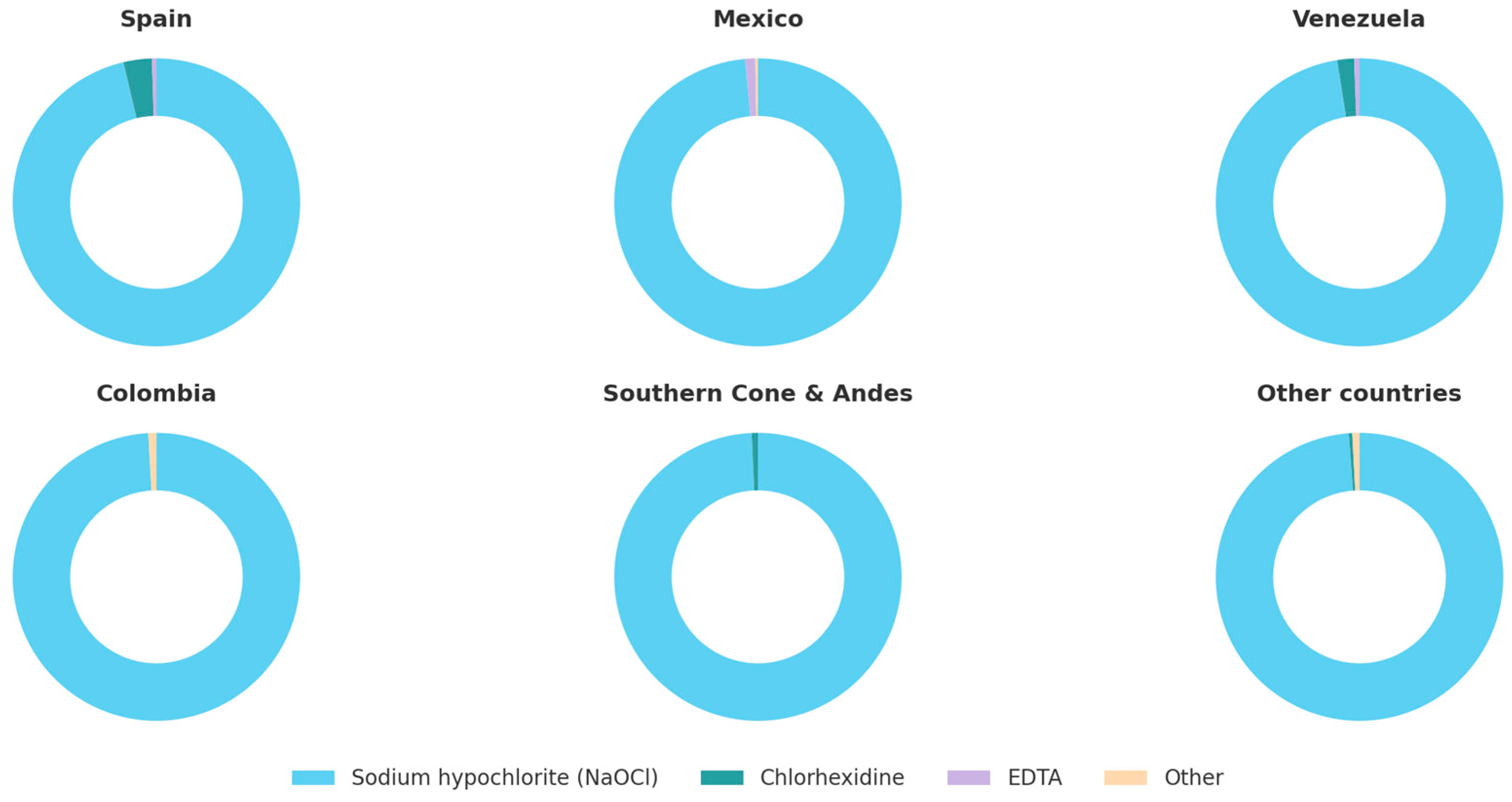

3.4. Instrumentation and Obturation

3.5. CBCT Utilization

3.6. Rubber Dam Isolation

3.7. Inter-Appointment Procedures and Medicaments

3.8. Apical Patency

3.9. Follow-Up

3.10. Postoperative Pain and Fracture After RCT

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheung, M.C.; Peters, O.A.; Parashos, P. Global survey of endodontic practice and adoption of newer technologies. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 1517–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambu, E.; Gori, B.; Marruganti, C.; Malvicini, G.; Bordone, A.; Giberti, L.; Grandini, S.; Gaeta, C. Influence of Calcified Canals Localization on the Accuracy of Guided Endodontic Therapy: A Case Series Study. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setzer, F.C.; Kratchman, S.I. Present status and future directions: Surgical endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55 (Suppl. S4), 1020–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, O.; Kopac, T. Recent Progress on the Applications of Nanomaterials and Nano-Characterization Techniques in Endodontics: A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamanca Ramos, M.; Aranguren, J.; Malvicini, G.; De Gregorio, C.; Bonilla, C.; Perez, A.R. Temperature-Dependent Effects on Cyclic Fatigue Resistance in Three Reciprocating Endodontic Systems: An In Vitro Study. Materials 2025, 18, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, J.A.; Mendez, S.P.; Malvicini, G.; Grandini, S.; Gaeta, C.; García Guerrero, A.P.; Miranda Robles, K.L.; Aranguren, J.; Pérez, A.R. Multimodal Evaluation of Three NiTi Rotary Systems: Clinical Simulation, Mechanical Testing, and Finite Element Analysis. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrin, P.; Neuhaus, K.W.; Lussi, A. The impact of loupes and microscopes on vision in endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2014, 47, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmberg, L.; Sturestam, A.; Fagring, A.; Björkner, A.E. Endodontic follow-up practices, sources of knowledge, and self-assessed treatment outcome among general dental practitioners in Sweden and Norway. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2020, 78, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.; Yang, M.; Kim, J.R. Prevalence of Teaching Apical Patency and Various Instrumentation and Obturation Techniques in United States Dental Schools: Two Decades Later. J. Endod. 2023, 49, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.C.; Parashos, P. Current endodontic practice and use of newer technologies in Australia and New Zealand. Aust. Dent. J. 2023, 68, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savani, G.M.; Sabbah, W.; Sedgley, C.M.; Whitten, B. Current trends in endodontic treatment by general dental practitioners: Report of a United States national survey. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.C.; Peters, O.A.; Parashos, P. Global cone-beam computed tomography adoption, usage and scan interpretation preferences of dentists and endodontists. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Zarza-Rebollo, A.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M.C.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Areal-Quecuty, V.; Martín-González, J. Evaluation of undergraduate Endodontic teaching in dental schools within Spain. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgarello, S.; Salvadori, M.; Mazzoleni, F.; Salvalai, V.; Francinelli, J.; Bertoletti, P.; Lorenzi, D.; Audino, E.; Garo, M.L. Urgent Dental Care During Italian Lockdown: A Cross-sectional Survey. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setzer, F.C.; Hinckley, N.; Kohli, M.R.; Karabucak, B. A Survey of Cone-beam Computed Tomographic Use among Endodontic Practitioners in the United States. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.; Zhu, Q.; Aseltine, R.H., Jr.; Kuo, C.L.; da Cunha Godoy, L.; Kaufman, B. A Survey on Cone-beam Computed Tomography Usage Among Endodontists in the United States. J. Endod. 2023, 49, 1559–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba-Hattab, R.; Taha, N.A.; Shaweesh, M.M.; Palma, P.J.; Abdulrab, S. Global trends in preclinical and clinical undergraduate endodontic education: A worldwide survey. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setzer, F.C.; Kohli, M.R.; Shah, S.B.; Karabucak, B.; Kim, S. Outcome of endodontic surgery: A meta-analysis of the literature--Part 2: Comparison of endodontic microsurgical techniques with and without the use of higher magnification. J. Endod. 2012, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, G.B.; Murgel, C.A. The use of the operating microscope in endodontics. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 54, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenele, R.C.; Gaêta-Araujo, H.; Jacobs, R. Cone beam computed tomography in dentistry: Clinical recommendations and indication-specific features. J. Dent. 2025, 159, 105781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiado, G.M.; Evangelista, K.; Freire, M.; Almeida, F.T.; Pacheco-Pereira, C.; Flores-Mir, C.; Cevidanes, L.H.S.; Ruelas, A.C.O.; Vasconcelos, K.F.; Preda, F.; et al. Orthodontists′ criteria for prescribing cone-beam computed tomography-a multi-country survey. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 1625–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gregorio, C.; Arias, A.; Navarrete, N.; Cisneros, R.; Cohenca, N. Differences in disinfection protocols for root canal treatments between general dentists and endodontists: A Web-based survey. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2015, 146, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojicic, S.; Zivkovic, S.; Qian, W.; Zhang, H.; Haapasalo, M. Tissue dissolution by sodium hypochlorite: Effect of concentration, temperature, agitation, and surfactant. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 1558–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Y.L.; Mann, V.; Gulabivala, K. A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment: Part 1: Periapical health. Int. Endod. J. 2011, 44, 583–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guivarc’h, M.; Jeanneau, C.; Giraud, T.; Pommel, L.; About, I.; Azim, A.A.; Bukiet, F. An international survey on the use of calcium silicate-based sealers in non-surgical endodontic treatment. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2020, 24, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejjeri, M.; Mezghanni, A.; Jaafoura, S.; Bellali, H. Prevalence and Influencing Factors of Rubber Dam Use among Tunisian Dentists: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2024, 14, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madarati, A.A. Why dentists don’t use rubber dam during endodontics and how to promote its usage? BMC Oral Health 2016, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrat, A.; Funkhouser, E.; Law, A.S.; Abusteit, O.; Mungia, R.; Nixdorf, D.R.; Lam, E.W.N.; Gilbert, G.H. Differences in clinical approaches of endodontists and general dentists when performing non-surgical root canal treatment: A prospective cohort study from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network PREDICT Project. Int. Endod. J. 2025, 58, 1408–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathorn, C.; Parashos, P.; Messer, H. Australian endodontists’ perceptions of single and multiple visit root canal treatment. Int Endod. J. 2009, 42, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madarati, A.A.; Zafar, M.S.; Sammani, A.M.N.; Mandorah, A.O.; Bani-Younes, H.A. Preference and usage of intracanal medications during endodontic treatment. Saudi Med. J. 2017, 38, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoof, M.; Zeini, N.; Haghani, J.; Sadr, S.; Mohammadalizadeh, S. Preferred materials and methods employed for endodontic treatment by Iranian general practitioners. Iran Endod. J. 2015, 10, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alobaid, M.A.; Bin Hassan, S.A.; Alfarhan, A.H.; Ali, S.; Hameed, M.S.; Syed, S. A Critical Evaluation of the Undergraduate Endodontic Teaching in Dental Colleges of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, A.M.P.; Lopes, C.B.; Vaz de Azevedo, K.R.; Rosana de Lima Ribeiro Andrade, H.T.; Vidal, F.; Souza Gonçalves, L.; Marques Ferreira, M.; de Carvalho Ferreira, D. Recall Rates of Patients in Endodontic Treatments: A Critical Review. Iran Endod. J. 2019, 14, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, H.F.; Kirkevang, L.L.; Peters, O.A.; El-Karim, I.; Krastl, G.; Del Fabbro, M.; Chong, B.S.; Galler, K.M.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Kebschull, M. Treatment of pulpal and apical disease: The European Society of Endodontology (ESE) S3-level clinical practice guideline. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56 (Suppl. S3), 238–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.; Patro, S.; Barman, D.; Jnaneshwar, A. Modern endodontic practices among dentists in India: A comparative cross-sectional nation-based survey. J. Conserv. Dent. 2020, 23, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.; Pawar, A.M.; Agustin Wahjuningrum, D.; Maniangat Luke, A.; Reda, R.; Testarelli, L. Connectivity and Integration of Instagram(®) Use in the Lives of Dental Students and Professionals: A Country-Wide Cross-Sectional Study Using the InstaAA© Questionnaire. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 2963–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalifa, K.S.; Al-Swuailem, A.S.; AlSheikh, R.; Muazen, Y.Y.; Al-Khunein, Y.A.; Halawany, H.; Al-Abidi, K.S. The use of social media for professional purposes among dentists in Saudi Arabia. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Spain | Mexico | Venezuela | Colombia | Southern Cone & Andes | Other Countries | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–5 years | 106 (48.4%) | 174 (49.3%) | 43 (26.5%) | 36 (33.3%) | 88 (33.3%) | 95 (37.7%) | 542 (39.9%) |

| 6–10 years | 58 (26.5%) | 75 (21.2%) | 36 (22.2%) | 21 (19.4%) | 69 (26.1%) | 52 (20.6%) | 311 (22.9%) |

| 11–20 years | 34 (15.5%) | 54 (15.3%) | 40 (24.7%) | 31 (28.7%) | 64 (24.2%) | 59 (23.4%) | 282 (20.8%) |

| >20 years | 21 (9.6%) | 50 (14.2%) | 43 (26.5%) | 20 (18.5%) | 43 (16.3%) | 46 (18.3%) | 223 (16.4%) |

| Undergraduate/ graduate only | 16 (7.3%) | 32 (9.1%) | 25 (15.4%) | 23 (21.3%) | 23 (8.7%) | 36 (14.3%) | 155 (11.4%) |

| Courses/ congresses | 15 (6.8%) | 42 (11.9%) | 80 (49.4%) | 9 (8.3%) | 50 (18.9%) | 44 (17.5%) | 240 (17.7%) |

| Modular postgraduate | 61 (27.9%) | 124 (35.1%) | 28 (17.3%) | 45 (41.7%) | 82 (31.1%) | 53 (21.0%) | 393 (28.9%) |

| Master ≥ 2 years | 100 (45.7%) | 122 (34.6%) | 20 (12.3%) | 26 (24.1%) | 83 (31.4%) | 88 (34.9%) | 439 (32.3%) |

| Currently in postgraduate program | 27 (12.3%) | 33 (9.3%) | 9 (5.6%) | 5 (4.6%) | 26 (9.8%) | 31 (12.3%) | 131 (9.6%) |

| Variable | Spain | Mexico | Venezuela | Colombia | Southern Cone & Andes | Other Countries | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnification | |||||||

| Microscope | 61 (27.9%) | 71 (20.1%) | 13 (8.0%) | 12 (11.1%) | 46 (17.1%) | 49 (19.8%) | 252 (18.6%) |

| Loupes | 100 (45.7%) | 200 (56.7%) | 105 (64.8%) | 63 (58.3%) | 144 (53.5%) | 140 (56.7%) | 752 (55.4%) |

| None | 58 (26.5%) | 82 (23.2%) | 44 (27.2%) | 33 (30.6%) | 79 (29.4%) | 58 (23.5%) | 354 (26.1%) |

| Irrigant of choice | |||||||

| NaOCl | 211 (96.3%) | 348 (98.6%) | 158 (97.5%) | 107 (99.1%) | 267 (99.3%) | 244 (98.8%) | 1335 (98.3%) |

| Chlorhexidine | 7 (3.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 13 (1.0%) |

| EDTA | 1 (0.5%) | 4 (1.1%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (0.4%) |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.8%) | 4 (0.3%) |

| Irrigation adjunct | |||||||

| Ultrasonic | 69 (31.5%) | 243 (68.8%) | 86 (53.1%) | 28 (25.9%) | 157 (58.4%) | 136 (55.1%) | 719 (52.9%) |

| Sonic | 181 (82.6%) | 320 (90.7%) | 111 (68.5%) | 88 (81.5%) | 221 (82.2%) | 209 (84.6%) | 1130 (83.2%) |

| Negative pressure | 5 (2.3%) | 12 (3.4%) | 13 (8.0%) | 5 (4.6%) | 11 (4.1%) | 8 (3.2%) | 54 (4.0%) |

| None | 16 (7.3%) | 4 (1.1%) | 8 (4.9%) | 5 (4.6%) | 14 (5.2%) | 6 (2.4%) | 53 (3.9%) |

| Obturation technique | |||||||

| Warm vertical | 87 (39.7%) | 47 (13.3%) | 10 (6.2%) | 5 (4.6%) | 30 (11.2%) | 35 (14.2%) | 214 (15.8%) |

| Cold lateral | 20 (9.1%) | 117 (33.1%) | 93 (57.4%) | 46 (42.6%) | 106 (39.4%) | 80 (32.4%) | 462 (34.0%) |

| Single cone | 28 (12.8%) | 61 (17.3%) | 21 (13.0%) | 20 (18.5%) | 37 (13.8%) | 44 (17.8%) | 211 (15.5%) |

| Carrier-based | 16 (7.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (1.2%) | 20 (1.5%) |

| Sealer type | |||||||

| Bioceramic | 22 (10.0%) | 74 (21.0%) | 50 (30.9%) | 16 (14.8%) | 44 (16.4%) | 51 (20.6%) | 257 (18.9%) |

| Epoxy-resin | 122 (55.7%) | 116 (32.9%) | 41 (25.3%) | 54 (50.0%) | 108 (40.1%) | 88 (35.6%) | 529 (39.0%) |

| Other | 75 (34.2%) | 166 (47.0%) | 71 (43.8%) | 39 (36.1%) | 118 (43.9%) | 109 (44.1%) | 578 (42.6%) |

| CBCT usage | |||||||

| Yes | 212 (96.8%) | 323 (91.5%) | 134 (82.7%) | 100 (92.6%) | 252 (93.7%) | 232 (93.9%) | 1253 (92.3%) |

| No | 7 (3.2%) | 30 (8.5%) | 28 (17.3%) | 8 (7.4%) | 17 (6.3%) | 15 (6.1%) | 105 (7.7%) |

| Variable | Category | Currently Postgraduate/ Master (n = 131) | Courses, Congresses (n = 240) | Bachelor’s Degree (n = 155) | Master (≥2 Years) (n = 439) | Modular Postgraduate (n = 393) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubber dam | Always | 128 (97.7%) | 186 (77.5%) | 121 (78.1%) | 433 (98.6%) | 366 (93.1%) |

| Occasionally | 3 (2.3%) | 53 (22.1%) | 25 (16.1%) | 5 (1.1%) | 27 (6.9%) | |

| Never | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 9 (5.8%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Endodontic sessions | One session (if possible) | 84 (64.1%) | 65 (27.1%) | 68 (43.9%) | 331 (75.4%) | 246 (62.6%) |

| Two sessions | 47 (35.9%) | 175 (72.9%) | 87 (56.1%) | 108 (24.6%) | 147 (37.4%) | |

| Obturation system | Lateral compaction | 33 (25.2%) | 136 (56.7%) | 80 (51.6%) | 84 (19.1%) | 129 (32.8%) |

| Vertical compaction | 27 (20.6%) | 10 (4.2%) | 11 (7.1%) | 103 (23.5%) | 63 (16.0%) | |

| Single cone | 20 (15.3%) | 47 (19.6%) | 25 (16.1%) | 52 (11.9%) | 67 (17.1%) | |

| All depending on the case | 49 (37.4%) | 41 (17.1%) | 35 (22.6%) | 196 (44.7%) | 130 (33.1%) | |

| Carrier-based | 2 (1.5%) | 6 (2.5%) | 4 (2.6%) | 4 (0.9%) | 4 (1.0%) | |

| Sealer Type | Resin-based | 50 (38.2%) | 84 (35.0%) | 69 (44.5%) | 165 (37.6%) | 162 (41.2%) |

| Bioceramics | 25 (19.1%) | 63 (26.3%) | 28 (18.1%) | 83 (18.9%) | 84 (21.4%) | |

| Zinc oxide–eugenol–based | 5 (3.8%) | 9 (3.8%) | 6 (3.9%) | 6 (1.4%) | 5 (1.3%) | |

| Mixed/other/depends | 51 (38.9%) | 84 (35.0%) | 52 (33.5%) | 185 (42.1%) | 142 (36.1%) | |

| Working length measurement | Both (apex locator + radiograph) | 90 (68.7%) | 128 (53.3%) | 74 (47.7%) | 230 (52.4%) | 226 (57.5%) |

| Apex locator only | 41 (31.3%) | 53 (22.1%) | 40 (25.8%) | 201 (45.8%) | 150 (38.2%) | |

| Radiographically only | 0 (0.0%) | 57 (23.8%) | 41 (26.5%) | 8 (1.8%) | 17 (4.3%) | |

| Instrumentation type | Combined (manual + rotary) | 118 (90.1%) | 158 (65.8%) | 88 (56.8%) | 399 (90.9%) | 339 (86.3%) |

| Manual only | 5 (3.8%) | 67 (27.9%) | 58 (37.4%) | 1 (0.2%) | 10 (2.5%) | |

| Rotary only | 8 (6.1%) | 15 (6.3%) | 9 (5.8%) | 39 (8.9%) | 44 (11.2%) | |

| Chlorhexidine concentration | 0.05% (0.0005) | 2 (1.5%) | 5 (2.1%) | 3 (1.9%) | — | 6 (1.5%) |

| 0.12% (0.0012) | 10 (7.6%) | 36 (15.0%) | 16 (10.3%) | 37 (8.4%) | 27 (6.9%) | |

| 2% (0.02) | 41 (31.3%) | 80 (33.3%) | 41 (26.5%) | 138 (31.4%) | 133 (33.8%) | |

| Do not use chlorhexidine | 78 (59.5%) | 119 (49.6%) | 95 (61.3%) | 264 (60.1%) | 227 (57.8%) | |

| NaOCl concentration | 0.5–2.5% | 16 (12.2%) | 65 (27.1%) | 40 (25.8%) | 50 (11.4%) | 62 (15.8%) |

| <0.5% | 5 (3.8%) | 17 (7.1%) | 14 (9.0%) | 4 (0.9%) | 11 (2.8%) | |

| >2.5–5.25% | 107 (81.7%) | 153 (63.8%) | 91 (58.7%) | 382 (87.0%) | 316 (80.4%) | |

| Unknown concentration | 3 (2.3%) | 5 (2.1%) | 10 (6.5%) | 3 (0.7%) | 4 (1.0%) | |

| Primary irrigant | Chlorhexidine | 1 (0.8%) | 6 (2.5%) | 1 (0.6%) | 4 (0.9%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| EDTA | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.8%) | |

| NaOCl (sodium hypochlorite) | 127 (97.0%) | 231 (96.3%) | 153 (98.7%) | 435 (99.1%) | 389 (99.0%) | |

| Other | 2 (1.5%) | 2 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Activation | Ultrasonic activation (PUI, passive ultrasonic) | 84 (64.1%) | 118 (49.2%) | 53 (34.2%) | 246 (56.0%) | 216 (55.0%) |

| Sonic activation | 38 (29.0%) | 44 (18.3%) | 46 (29.7%) | 153 (34.9%) | 129 (32.8%) | |

| Negative apical pressure | 3 (2.3%) | 16 (6.7%) | 10 (6.5%) | 10 (2.3%) | 14 (3.6%) | |

| None/ manual/other | 6 (4.6%) | 62 (25.8%) | 46 (29.7%) | 30 (6.8%) | 34 (8.7%) | |

| Magnification system | Loupes | 84 (64.1%) | 143 (59.6%) | 65 (41.9%) | 235 (53.5%) | 225 (57.3%) |

| Microscope | 22 (16.8%) | 8 (3.3%) | 14 (9.0%) | 149 (33.9%) | 59 (15.0%) | |

| None | 25 (19.1%) | 89 (37.1%) | 76 (49.0%) | 55 (12.5%) | 109 (27.7%) | |

| CBCT Indications | Multiple indications (all/most of the above; generic/other) | 102 (77.9%) | 115 (47.9%) | 81 (52.3%) | 346 (78.8%) | 272 (69.2%) |

| Complex anatomy (incl. complex cases) | 12 (9.2%) | 29 (12.1%) | 15 (9.7%) | 36 (8.2%) | 52 (13.2%) | |

| Retreatment | 5 (3.8%) | 23 (9.6%) | 18 (11.6%) | 13 (3.0%) | 22 (5.6%) | |

| Apical surgery | 8 (6.1%) | 10 (4.2%) | 17 (11.0%) | 29 (6.6%) | 27 (6.9%) | |

| None/do not use/no access/don’t know | 4 (3.1%) | 63 (26.3%) | 24 (15.5%) | 15 (3.4%) | 20 (5.1%) | |

| clinical time in endodontics | 100% (exclusive endodontist) | 29 (22.1%) | 11 (4.6%) | 29 (18.7%) | 244 (55.6%) | 145 (36.9%) |

| <50% | 38 (29.0%) | 131 (54.6%) | 73 (47.1%) | 32 (7.3%) | 93 (23.7%) | |

| >50% | 64 (48.9%) | 98 (40.8%) | 53 (34.2%) | 163 (37.1%) | 155 (39.4%) | |

| Years of experience in endodontics | 1–5 years | 115 (87.8%) | 80 (33.3%) | 80 (51.6%) | 126 (28.7%) | 141 (35.9%) |

| 6–10 years | 13 (9.9%) | 60 (25.0%) | 23 (14.8%) | 106 (24.1%) | 109 (27.7%) | |

| 11–20 years | 2 (1.5%) | 48 (20.0%) | 27 (17.4%) | 114 (26.0%) | 91 (23.2%) | |

| >20 years | 1 (0.8%) | 52 (21.7%) | 25 (16.1%) | 93 (21.2%) | 52 (13.2%) |

| Predictor | OR (95% CI) | z | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country: Mexico | 1.52 (0.84–2.74) | 1.38 | 0.169 |

| Country: Other countries | 1.49 (0.81–2.76) | 1.28 | 0.201 |

| Country: Southern Cone & Andes | 1.12 (0.60–2.09) | 0.37 | 0.714 |

| Country: Spain | 0.64 (0.32–1.28) | −1.27 | 0.204 |

| Country: Venezuela | 2.56 (1.35–4.84) | 2.89 | 0.004 |

| Training: Postgraduate | 0.98 (0.72–1.34) | −0.12 | 0.908 |

| Experience (per category increase) | 0.98 (0.86–1.11) | −0.32 | 0.749 |

| Predictor | OR (95% CI) | z | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country: Mexico | 0.71 (0.30–1.64) | −0.81 | 0.418 |

| Country: Other countries | 1.31 (0.53–3.27) | 0.58 | 0.559 |

| Country: Southern Cone & Andes | 1.15 (0.47–2.81) | 0.30 | 0.766 |

| Country: Spain | 1.75 (0.60–5.10) | 1.02 | 0.308 |

| Country: Venezuela | 0.65 (0.27–1.53) | −1.00 | 0.319 |

| Training: Postgraduate | 5.72 (3.63–9.02) | 7.50 | 0.000 |

| Experience (per category increase) | 1.01 (0.84–1.22) | 0.11 | 0.909 |

| Variable | Spain | Mexico | Venezuela | Colombia | Southern Cone & Andes | Other Countries | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubber dam | |||||||

| Always | 217 (99.1%) | 353 (100.0%) | 160 (98.8%) | 106 (98.1%) | 266 (98.9%) | 245 (99.2%) | 1347 (99.2%) |

| Not always | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Treatment sessions | |||||||

| Single visit | 185 (84.5%) | 178 (50.4%) | 38 (23.5%) | 85 (78.7%) | 165 (61.3%) | 143 (57.9%) | 794 (58.5%) |

| Multiple visits | 34 (15.5%) | 175 (49.6%) | 124 (76.5%) | 23 (21.3%) | 104 (38.7%) | 104 (42.1%) | 564 (41.5%) |

| Calcium hydroxide | |||||||

| Yes | 170 (77.6%) | 253 (71.7%) | 99 (61.1%) | 82 (75.9%) | 183 (68.0%) | 167 (67.6%) | 954 (70.3%) |

| No | 3 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (1.5%) | 2 (0.8%) | 11 (0.8%) |

| Apical patency | |||||||

| Yes | 69 (31.5%) | 156 (44.2%) | 108 (66.7%) | 64 (59.3%) | 160 (59.5%) | 125 (50.6%) | 682 (50.2%) |

| No | 1 (0.5%) | 9 (2.5%) | 5 (3.1%) | 1 (0.9%) | 7 (2.6%) | 9 (3.6%) | 32 (2.4%) |

| Follow-up | |||||||

| ≤6 months | 116 (53.0%) | 134 (38.0%) | 63 (38.9%) | 45 (41.7%) | 91 (33.8%) | 106 (42.9%) | 555 (40.9%) |

| 1 year | 11 (5.0%) | 4 (1.1%) | 3 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (1.5%) | 5 (2.0%) | 27 (2.0%) |

| Only if symptoms | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Postoperative pain | |||||||

| Common | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Uncommon | 166 (75.8%) | 321 (90.9%) | 146 (90.1%) | 92 (85.2%) | 240 (89.2%) | 208 (84.2%) | 1173 (86.4%) |

| Never | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Fracture after RCT | |||||||

| Common | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Uncommon | 125 (57.1%) | 236 (66.9%) | 119 (73.5%) | 84 (77.8%) | 214 (79.6%) | 172 (69.6%) | 950 (70.0%) |

| Never | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Variable | Category | Currently Postgraduate/ Master (n = 131) | Courses, Congresses (n = 240) | Bachelor’s Degree (n = 155) | Master (≥2 Years) (n = 439) | Modular Postgraduate (n = 393) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubber dam | Always | 128 (97.7%) | 186 (77.5%) | 121 (78.1%) | 433 (98.6%) | 366 (93.1%) |

| Occasionally | 3 (2.3%) | 53 (22.1%) | 25 (16.1%) | 5 (1.1%) | 27 (6.9%) | |

| Never | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 9 (5.8%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Treatment sessions | Single visit | 84 (64.1%) | 65 (27.1%) | 68 (43.9%) | 331 (75.4%) | 246 (62.6%) |

| Multiple visits | 47 (35.9%) | 175 (72.9%) | 87 (56.1%) | 108 (24.6%) | 147 (37.4%) | |

| Patency maintenance | As often as possible | 47 (82.5%) | 132 (91.0%) | 73 (82.0%) | 196 (89.5%) | 190 (89.6%) |

| Always | 2 (3.5%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.9%) | 4 (1.9%) | |

| Never/not important | 8 (14.0%) | 10 (6.9%) | 16 (18.0%) | 12 (5.5%) | 16 (7.5%) | |

| Other/depends | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (4.1%) | 2 (0.9%) | |

| Pre-operative x-Ray | Always | 37 (64.9%) | 66 (45.5%) | 44 (49.4%) | 134 (61.2%) | 113 (53.3%) |

| Sometimes (if in doubt) | 20 (35.1%) | 70 (48.3%) | 38 (42.7%) | 82 (37.4%) | 96 (45.3%) | |

| Never | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (6.2%) | 7 (7.9%) | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (1.4%) | |

| Calcium Hydroxide | Always | 52 (39.7%) | 111 (46.3%) | 71 (45.8%) | 164 (37.4%) | 171 (43.5%) |

| Only if necrotic/retreatment/suppuration | 70 (53.4%) | 109 (45.4%) | 75 (48.4%) | 221 (50.3%) | 190 (48.3%) | |

| Case-dependent/other conditional | 8 (6.1%) | 8 (3.3%) | 7 (4.5%) | 42 (9.6%) | 23 (5.9%) | |

| Never | 1 (0.8%) | 12 (5.0%) | 2 (1.3%) | 12 (2.7%) | 9 (2.3%) | |

| Working length measurements | Both (apex locator + radiograph) | 90 (68.7%) | 128 (53.3%) | 74 (47.7%) | 230 (52.4%) | 226 (57.5%) |

| Apex locator only | 41 (31.3%) | 53 (22.1%) | 40 (25.8%) | 201 (45.8%) | 150 (38.2%) | |

| Radiographically only | 0 (0.0%) | 57 (23.8%) | 41 (26.5%) | 8 (1.8%) | 17 (4.3%) | |

| Postoperative pain | Uncommon | 107 (81.7%) | 213 (88.8%) | 131 (84.5%) | 374 (85.2%) | 348 (88.6%) |

| Common | 21 (16.0%) | 20 (8.3%) | 24 (15.5%) | 61 (13.9%) | 41 (10.4%) | |

| Frequent | 3 (2.3%) | 7 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.9%) | 4 (1.0%) | |

| Fracture after RCT | Uncommon | 93 (71.0%) | 174 (72.5%) | 108 (69.7%) | 280 (63.8%) | 295 (75.1%) |

| Common | 34 (26.0%) | 60 (25.0%) | 41 (26.5%) | 143 (32.6%) | 78 (19.9%) | |

| Frequent | 4 (3.1%) | 6 (2.5%) | 6 (3.9%) | 16 (3.6%) | 20 (5.1%) | |

| Endodontic success | Both clinical & radiographic | 115 (87.8%) | 192 (80.0%) | 133 (85.8%) | 394 (89.8%) | 362 (92.1%) |

| Radiographic only | 1 (0.8%) | 5 (2.1%) | 3 (1.9%) | 6 (1.4%) | 3 (0.8%) | |

| Clinical only (no signs/symptoms) | 15 (11.5%) | 41 (17.1%) | 18 (11.6%) | 38 (8.7%) | 28 (7.1%) | |

| None of the above | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.8%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piñas-Alonzo, R.; Pérez, A.R.; Aranguren, J.; Vieira, G.C.S.; Paz, J.C.; Saavedra, J.; Guerrero Ferreccio, J.; Grandini, S.; Malvicini, G. Patterns of Endodontic Practice and Technological Uptake Across Training Levels in Spain and Latin America: Results from a Multicountry Survey of 1358 Clinicians. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120558

Piñas-Alonzo R, Pérez AR, Aranguren J, Vieira GCS, Paz JC, Saavedra J, Guerrero Ferreccio J, Grandini S, Malvicini G. Patterns of Endodontic Practice and Technological Uptake Across Training Levels in Spain and Latin America: Results from a Multicountry Survey of 1358 Clinicians. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):558. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120558

Chicago/Turabian StylePiñas-Alonzo, Rocío, Alejandro R. Pérez, José Aranguren, Gaya C. S. Vieira, Juan Carlos Paz, Juan Saavedra, Jenny Guerrero Ferreccio, Simone Grandini, and Giulia Malvicini. 2025. "Patterns of Endodontic Practice and Technological Uptake Across Training Levels in Spain and Latin America: Results from a Multicountry Survey of 1358 Clinicians" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120558

APA StylePiñas-Alonzo, R., Pérez, A. R., Aranguren, J., Vieira, G. C. S., Paz, J. C., Saavedra, J., Guerrero Ferreccio, J., Grandini, S., & Malvicini, G. (2025). Patterns of Endodontic Practice and Technological Uptake Across Training Levels in Spain and Latin America: Results from a Multicountry Survey of 1358 Clinicians. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120558