Fracture Resistance of Endodontically Treated Teeth with Different Perforation Diameters: An In Vitro Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Selection and Preparation

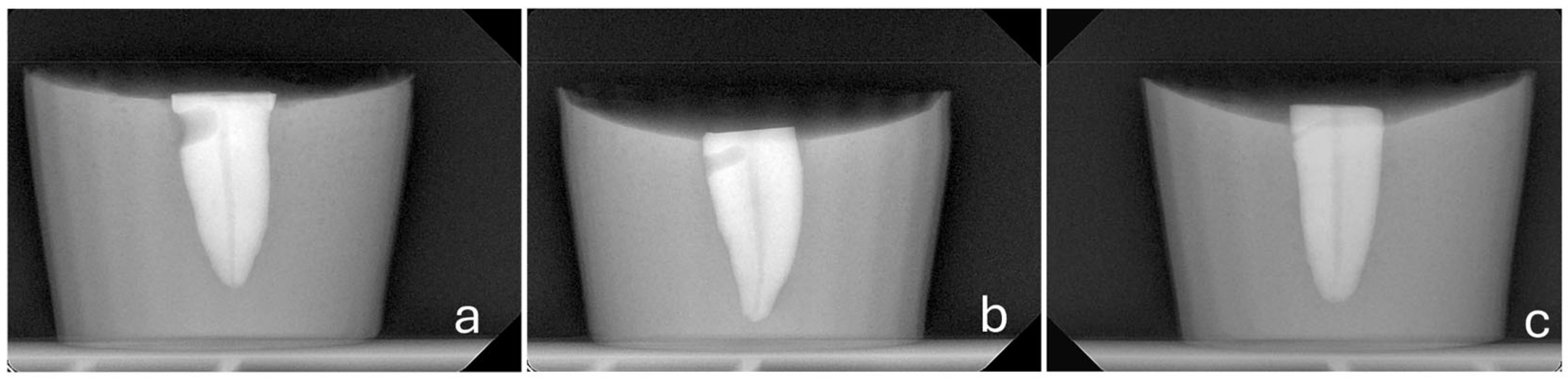

- A consistent perforation diameter. High-speed round burs with diameters of 2.1 mm, 1 mm and 0.5 mm (SS White, Lakewood, NJ, USA) were used for the Groups 3, 4 and 5, respectively. Each bur was used once and then discarded.

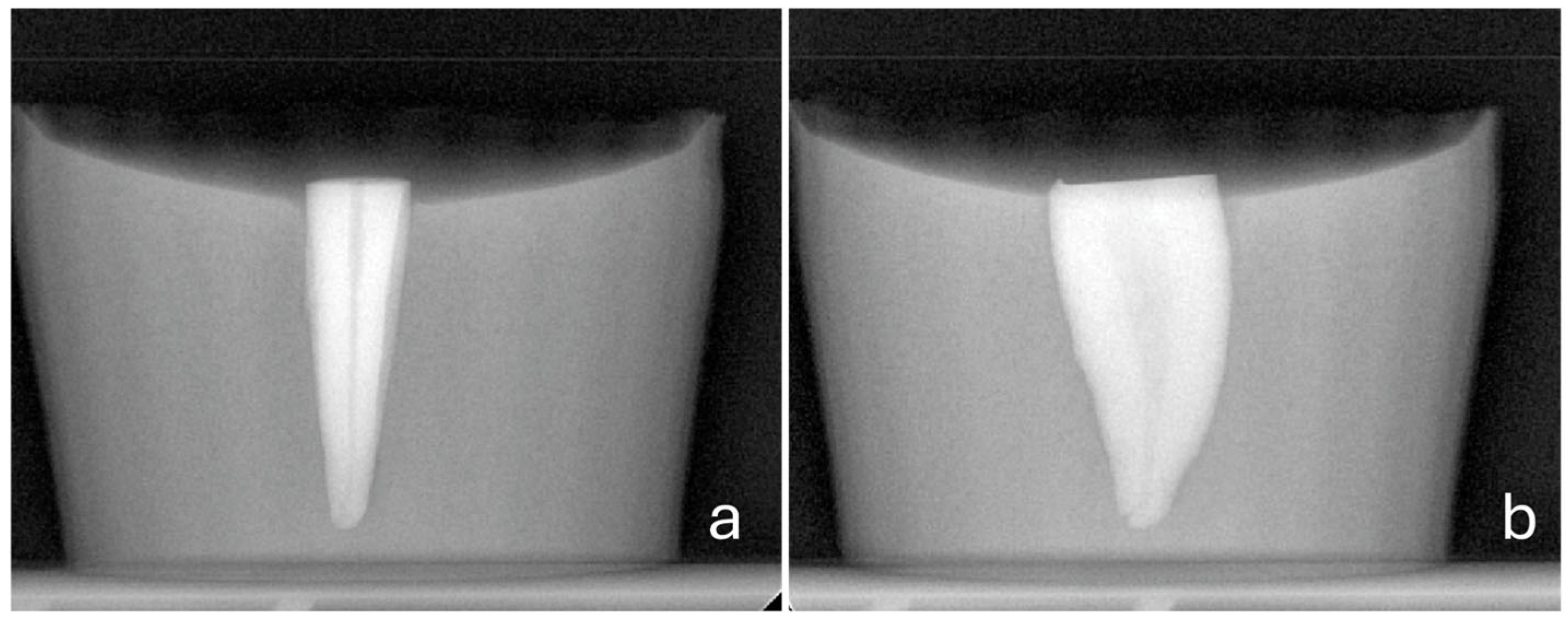

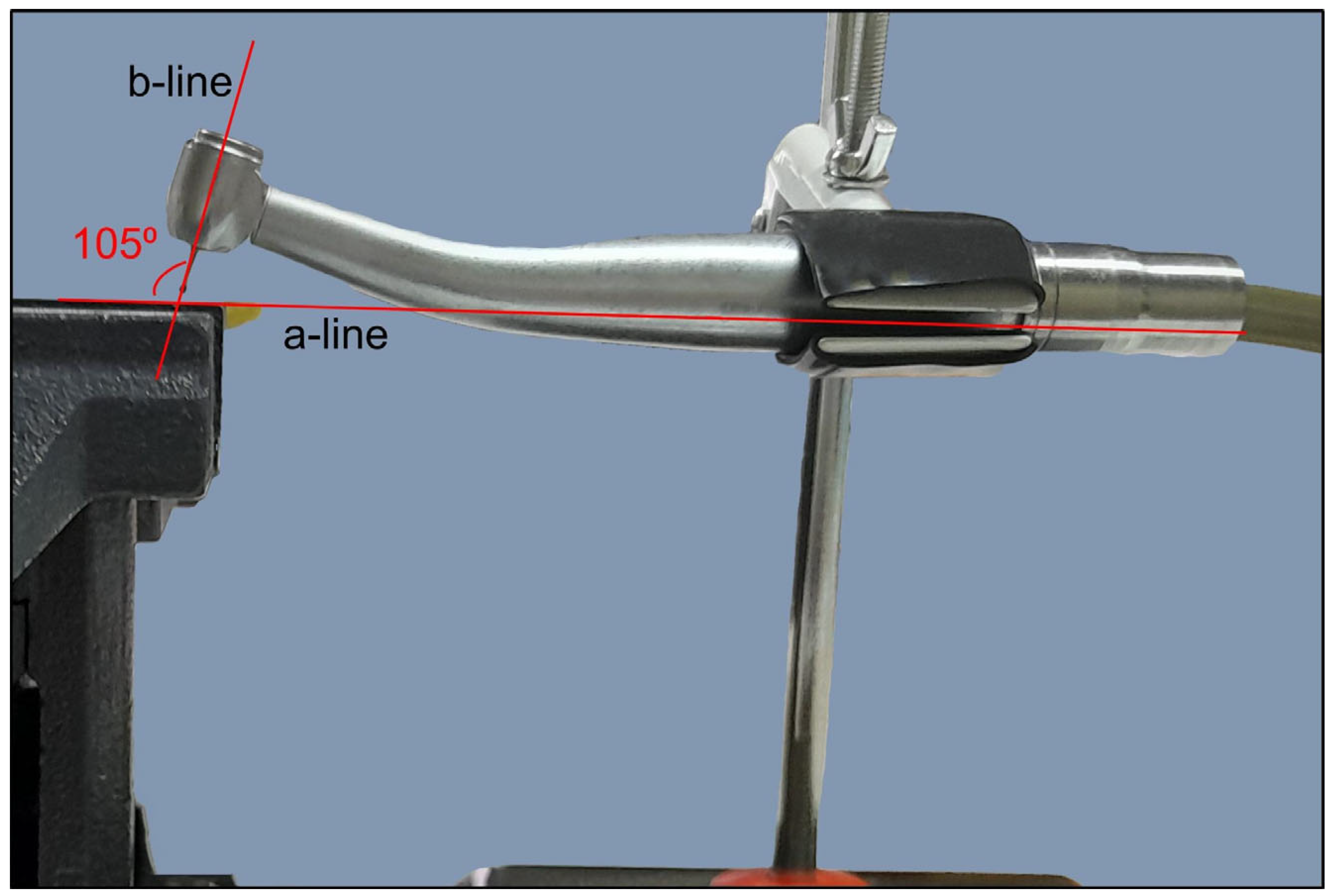

- A steady direction of perforation. Teeth were secured in a vise with their buccal surfaces parallel to the horizontal plane. The high-speed handpiece was also fixed in a horizontal position using a custom-made apparatus that allowed only downward vertical movement. Buccal diagonal perforations, starting 3 mm apical to the coronal surface of the teeth, were created under water cooling with a steady angle of 105° between the external surface of the root and the shank of the bur (Figure 2 and Figure 3). A #35-K stainless steel hand file (Dentsply, Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) inside the root canal prevented the overextension of the perforation to the lingual surface of the root.

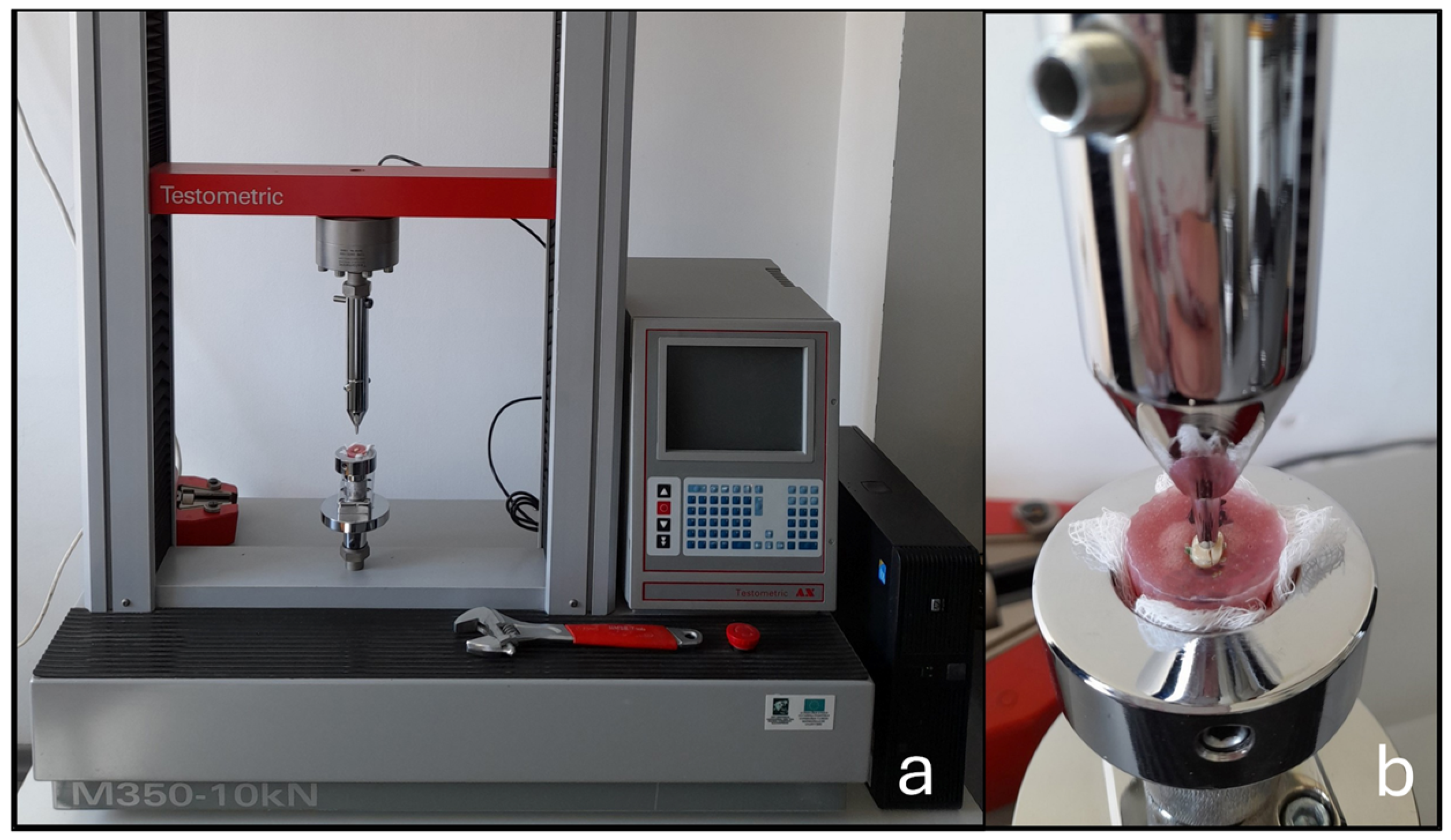

2.2. Fracture Resistance Testing

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FR | fracture resistance |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| BL | buccolingual |

| MD | mesiodistal |

| N | newtons |

| mm | millimeter |

| g | gram |

References

- American Association of Endodontists. Glossary of Endodontic Terms; American Association of Endodontists: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Tibúrcio-Machado, C.S.; Michelon, C.; Zanatta, F.B.; Gomes, M.S.; Marin, J.A.; Bier, C.A. The global prevalence of apical periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 712–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-López, M.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Martín-González, J.; Montero-Miralles, P.; Saúco-Márquez, J.J.; Segura-Egea, J.J. Prevalence of root canal treatment worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 1105–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rama Sowmya, M.; Raghu, S. Clinical practice guidelines on endodontic mishaps that occur during cleaning and shaping. Int. J. Dent. Oral. Sci. 2021, 8, 3607–3612. [Google Scholar]

- Estrela, C.; Decurcio, D.A.; Rossi-Fedele, G.; Silva, J.A.; Guedes, O.A.; Borges, Á.H. Root perforations: A review of diagnosis, prognosis and materials. Braz. Oral Res. 2018, 32, e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsesis, I.; Rosenberg, E.; Faivishevsky, V.; Kfir, A.; Katz, M.; Rosen, E. Prevalence and associated periodontal status of teeth with root perforation: A retrospective study of 2,002 patients’ medical records. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 797–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadis, G.I.; Lambrianidis, T.P. Technical quality of root canal treatment and detection of iatrogenic errors in an undergraduate dental clinic. Int. Endod. J. 2005, 38, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, Z.; Trope, M. Root perforations: Classification and treatment choices based on prognostic factors. Endod. Dent. Traumatol. 1996, 12, 255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Reeh, E.S.; Messer, H.H.; Douglas, W.H. Reduction in tooth stiffness as a result of endodontic and restorative procedures. J. Endod. 1989, 15, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PradeepKumar, A.R.; Shemesh, H.; Nivedhitha, M.S.; Hashir, M.M.J.; Arockiam, S.; Uma Maheswari, T.N.; Natanasabapathy, V. Diagnosis of vertical root fractures by cone-beam computed tomography in root-filled teeth with confirmation by direct visualization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 1198–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Soliman, P.S.; Roshdy, N.N.; Fouda, M.Y. Assessment of fracture resistance in teeth with simulated perforating internal root resorption cavities repaired with Biodentine, Retro MTA and Portland cement (a comparative in vitro study). Acta Sci. Dent. Sci. 2021, 5, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, W.A.; Alghamdi, F.; Aljahdali, E. Strengthening effect of bioceramic cement when used to repair simulated internal resorption cavities in endodontically treated teeth. Dent. Med. Probl. 2020, 57, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, M.M. Fracture Resistance of Simulated External Cervical Resorption in Anterior Teeth Restored with and Without a Fiber Post. Master’s Thesis, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Türker, S.A.; Uzunoğlu, E.; Sungur, D.D.; Tek, V. Fracture resistance of teeth with simulated perforating internal resorption cavities repaired with different calcium silicate–based cements and backfilling materials. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 860–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, W.; Li, Y.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Y. Fracture resistance and stress distribution of repairing endodontically treated maxillary first premolars with severe non-carious cervical lesions. Dent. Mater. J. 2018, 37, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulusoy, Ö.İ.; Paltun, Y.N. Fracture resistance of roots with simulated internal resorption defects and obturated using different hybrid techniques. J. Dent. Sci. 2017, 12, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudeja, C.; Taneja, S.; Kumari, M.; Singh, N. An in vitro comparison of effect on fracture strength, pH and calcium ion diffusion from various biomimetic materials when used for repair of simulated root resorption defects. J. Conserv. Dent. 2015, 18, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, B.; Pamir, T.; Baltaci, A.; Orman, M.N.; Turk, T. Effect of storage solutions on microhardness of crown enamel and dentin. Eur. J. Dent. 2015, 9, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, D.L.; Matheny, H.E.; Nicholls, J.I. An in vitro study of spreader loads required to cause vertical root fracture during lateral condensation. J. Endod. 1983, 9, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoldas, O.; Yilmaz, S.; Atakan, G.; Kuden, C.; Kasan, Z. Dentinal microcrack formation during root canal preparations by different NiTi rotary instruments and the self-adjusting file. J. Endod. 2012, 38, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.J.; Pizi, E.C.; Fonseca, R.B.; Martins, L.R. Influence of root embedment material and periodontal ligament simulation on fracture resistance tests. Braz. Oral Res. 2005, 19, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabert, K.C.; Caputo, A.A.; Abou-Rass, M. Tooth fracture: A comparison of endodontic and restorative treatments. J. Endod. 1978, 4, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, M.; Metzdorf, G.; Fokkinga, W.; Watzke, R.; Sterzenbach, G.; Bayne, S.; Rosentritt, M. Influence of test parameters on in vitro fracture resistance of post-endodontic restorations: A structured review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2009, 36, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Puleio, F.; Lo Giudice, G.; Militi, A.; Bellezza, U.; Lo Giudice, R. Does low-taper root canal shaping decrease the risk of root fracture? A systematic review. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, J.S. An investigation into the importance of the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone as supporting structures in finite element studies. J. Oral Rehabil. 2001, 28, 425–432. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, G.R.; Silva, N.R.; Soares, P.V.; Costa, A.R.; Fernandes-Neto, A.J.; Soares, C.J. Influence of different load application devices on fracture resistance of restored premolars. Braz. Dent. J. 2012, 23, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | ANOVA (p-Values) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL (mm) | 7.82 ± 0.55 | 7.86 ± 0.60 | 7.82 ± 0.59 | 7.70 ± 0.56 | 7.71 ± 0.59 | 0.933 |

| MD (mm) | 4.62 ±0.15 | 4.63 ± 0.24 | 4.68 ± 0.15 | 4.72 ± 0.29 | 4.51 ± 0.18 | 0.136 |

| Weight (g) | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 0.550 |

| Force (N) | 342.68 ± 146.45 | 322.96 ± 98.62 | 214.65 ± 71.32 | 212.66 ± 77.89 | 307.14 ± 109.16 | 0.003 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kakoura, F.; Lyroudia, K.; Economides, N.; Dimitriadis, D.; Mikrogeorgis, G. Fracture Resistance of Endodontically Treated Teeth with Different Perforation Diameters: An In Vitro Analysis. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010012

Kakoura F, Lyroudia K, Economides N, Dimitriadis D, Mikrogeorgis G. Fracture Resistance of Endodontically Treated Teeth with Different Perforation Diameters: An In Vitro Analysis. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleKakoura, Flora, Kleoniki Lyroudia, Nikolaos Economides, Dimitrios Dimitriadis, and Georgios Mikrogeorgis. 2026. "Fracture Resistance of Endodontically Treated Teeth with Different Perforation Diameters: An In Vitro Analysis" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010012

APA StyleKakoura, F., Lyroudia, K., Economides, N., Dimitriadis, D., & Mikrogeorgis, G. (2026). Fracture Resistance of Endodontically Treated Teeth with Different Perforation Diameters: An In Vitro Analysis. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010012