Clinical Management of Cervical Restorations with Closing Gap Technique: A Follow-Up of Two Cases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

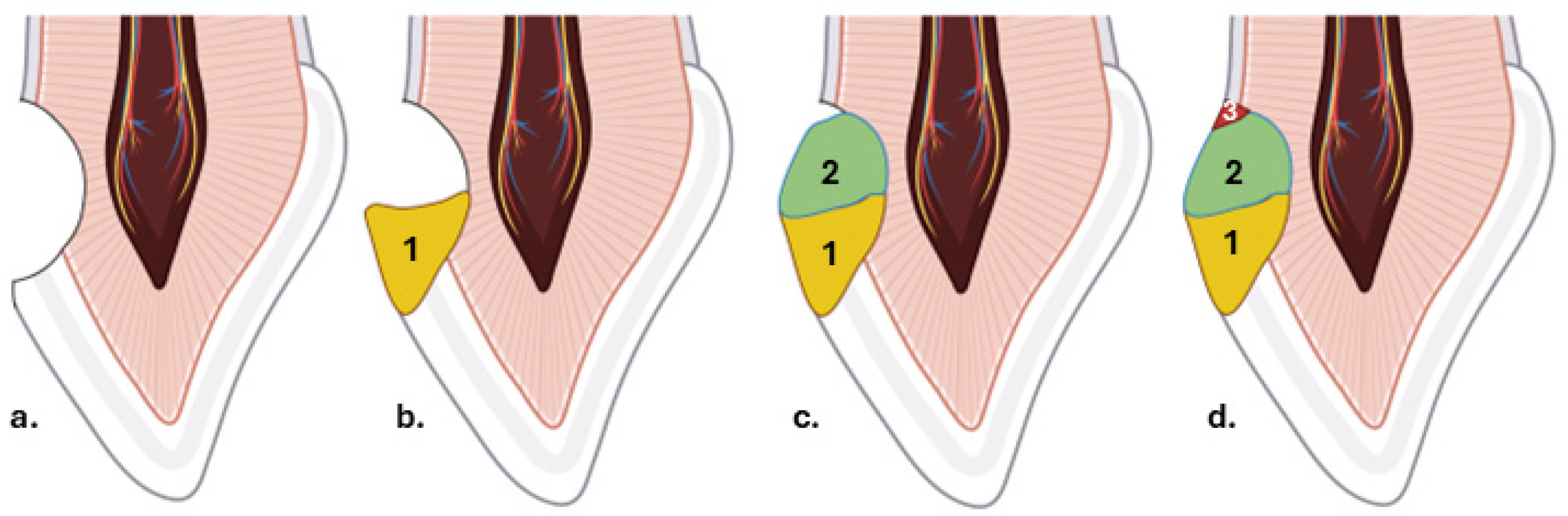

Description of the Closing Gap Technique

3. Results

3.1. Presentation of Clinical Case #1

3.1.1. Patient Information

3.1.2. Clinical Findings and Diagnosis

3.1.3. Therapeutic Intervention

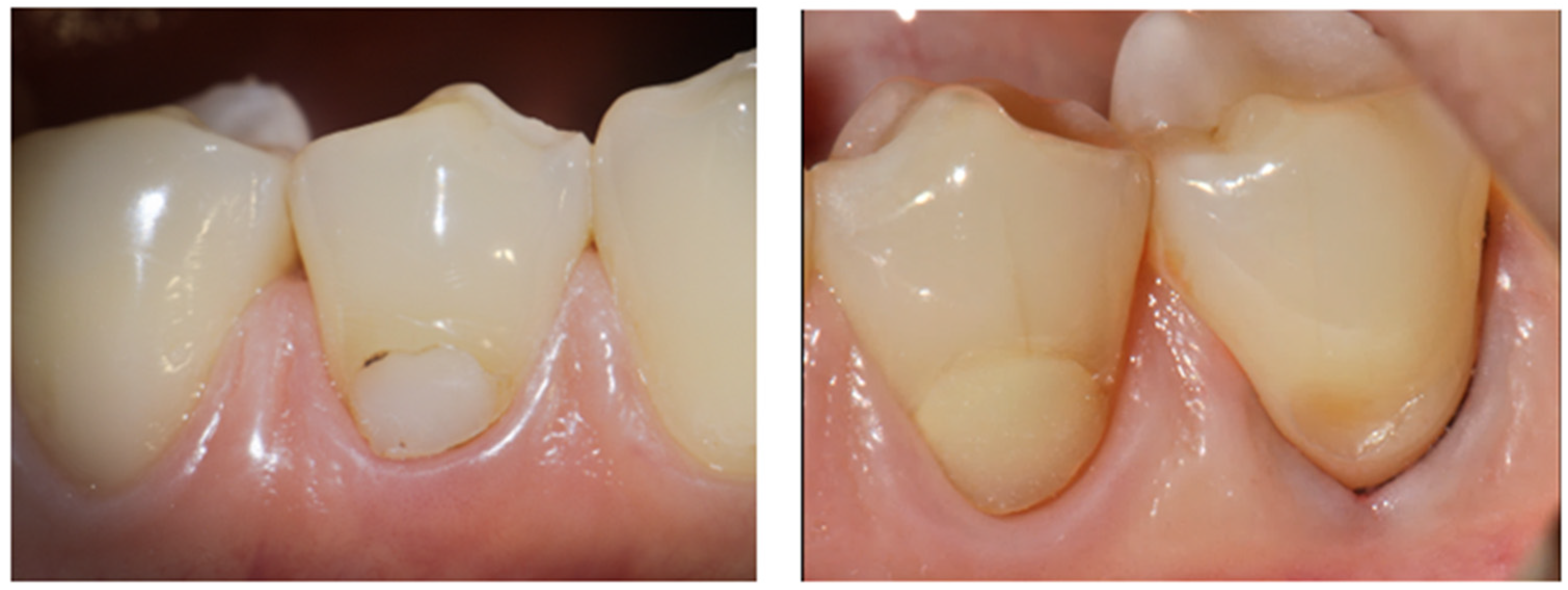

3.1.4. Follow Up and Outcomes

3.2. Presentation of Clinical Case #2

3.2.1. Patient Information

3.2.2. Clinical Findings and Diagnosis

3.2.3. Therapeutic Intervention

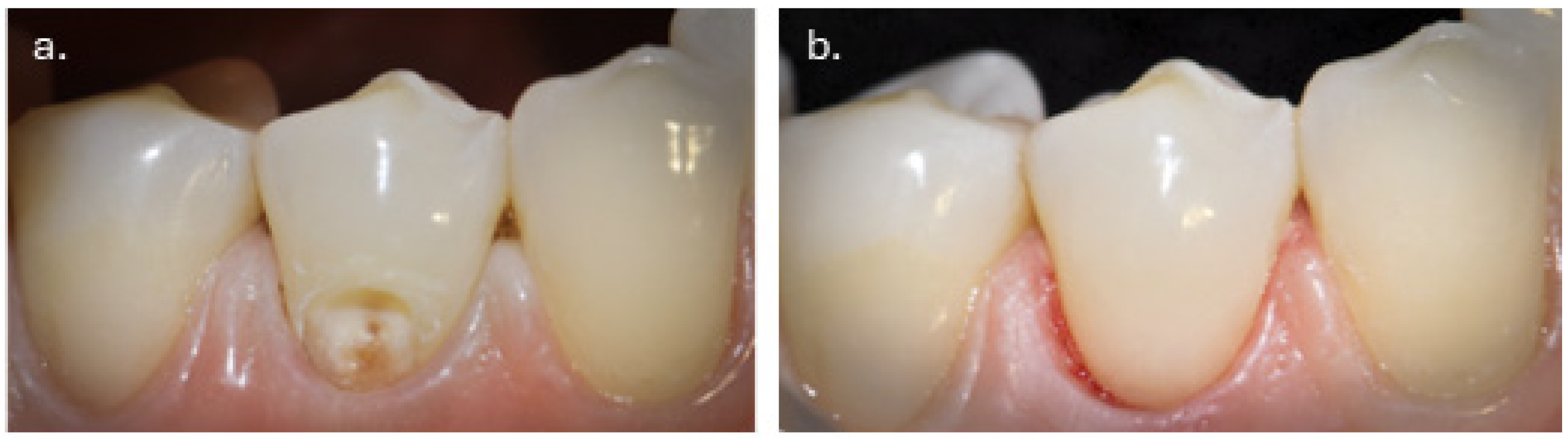

3.2.4. Follow Up and Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Study and the Closing Gap Technique

4.2. Clinical Significance of the Study and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NCCLs | Non-caries cervical lesions |

References

- Dawoud, B.; Abou-Auf, E.; Shaalan, O. 24-Month Clinical Evaluation of Cervical Restorations Bonded Using Radio-Opaque Universal Adhesive Compared to Conventional Universal Adhesive in Carious Cervical Lesions: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Cho, J.; Lee, Y.; Cho, B.-H. The Survival of Class V Composite Restorations and Analysis of Marginal Discoloration. Oper. Dent. 2017, 42, E93–E101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreweck, F.D.S.; Burey, A.; de Oliveira Dreweck, M.; Loguercio, A.D.; Reis, A. Adhesive Strategies in Cervical Lesions: Systematic Review and a Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2021, 25, 2495–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaple Gil, A.M.; Pereda Vázquez, L.; Santiesteban Velázquez, M.; Ortiz Santiago, L.L. Restorative and Adhesive Strategies for Cervical Carious Lesions: A Systematic Review, Pairwise and Network Meta-Analysis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyovich, M.; Bissada, N.; Teich, S.; Demko, C.; Ricchetti, P. Treatment of Noncarious Cervical Lesions by a Subepithelial Connective Tissue Graft Versus a Composite Resin Restoration. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2014, 34, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, F.C.; Soeroso, Y.; Hutomo, D.I.; Harsas, N.A.; Sulijaya, B. Effectiveness of Restorative Materials on Combined Periodontal-Restorative Treatment of Gingival Recession with Cervical Lesion: A Systematic Review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AL-Gailani, U.; Alqaysi, S. Estimation of the Gingival Microleakage of Two Composite Resins with Three Insertion Techniques for Class V Restorations (In-Vitro Comparative Study). Sulaimani Dent. J. 2019, 6, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathpour, K.; Bazazzade, A.; Mirmohammadi, H. A Comparative Study of Cervical Composite Restorations Microleakage Using Dental Universal Bonding and Two-Step Self-Etch Adhesive. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2021, 22, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, N.; Raykovska, M.; Koytchev, E.; Gusiyska, A. Biomimetic Strategies and Adhesive Protocols in the Restoration of Severely Compromised Posterior Teeth—A Contemporary Review Study. J. IMABAnnu. Proc. (Sci. Pap.) 2025, 31, 6542–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigova, R.; Hristov, K. Micro-Computed Tomography Assessment of Voids and Volume Changes in Bulk-Fill Restoration with Stamp Technique. Materials 2025, 18, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieplik, F.; Scholz, K.J.; Tabenski, I.; May, S.; Hiller, K.-A.; Schmalz, G.; Buchalla, W.; Federlin, M. Flowable Composites for Restoration of Non-Carious Cervical Lesions: Results after Five Years. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, e428–e437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battancs, E.; Fráter, M.; Sáry, T.; Gál, E.; Braunitzer, G.; Szabó P., B.; Garoushi, S. Fracture Behavior and Integrity of Different Direct Restorative Materials to Restore Noncarious Cervical Lesions. Polymers 2021, 13, 4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.d.R.; Gonzalez, M.R.; Prado, N.A.S.; de Miranda, M.S.F.; Macêdo, M.d.A.; Fernandes, B.M.P. Restoration of Noncarious Cervical Lesions: When, Why, and How. Int. J. Dent. 2012, 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecie, R.; Krejci, I.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; Bortolotto, T. Noncarious Cervical Lesions—A Clinical Concept Based on the Literature Review. Part 1: Prevention. Am. J. Dent. 2011, 24, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fernández, E.; Gil, A.C.; Caviedes, R.; Díaz, L.; Bersezio, C. Clinical Longevity of Direct Dental Restorations: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimeh, S.; Vaidyanathan, J.; Houpt, M.L.; Vaidyanathan, T.K.; Von Hagen, S. Microleakage of Compomer Class V Restorations: Effect of Load Cycling, Thermal Cycling, and Cavity Shape Differences. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2000, 83, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lührs, A.; Jacker-Guhr, S.; Günay, H.; Herrmann, P. Composite Restorations Placed in Non-carious Cervical Lesions—Which Cavity Preparation Is Clinically Reliable? Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2020, 6, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.M.d.O.; Tribst, J.P.M.; Matos, F.d.S.; Platt, J.A.; Caneppele, T.M.F.; Borges, A.L.S. Polymerization Shrinkage Stresses in Different Restorative Techniques for Non-Carious Cervical Lesions. J. Dent. 2018, 76, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attin, T. Introduction of a New Technique for Adhesive Restorations of Cervical Lesions. SWISS Dent. J. SSO Sci. Clin. Top. 2025, 135, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Closing Gap Technique. The Perfect Seal in Class 5 Restorations. Available online: https://Www.Styleitaliano.Org/the-Closing-Gap-Technique-the-Perfect-Seal-in-Class-5-Restorations/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Dhammayannarangsi, P.; Na Lampang, S.; Traithipsirikul, P.; Supamongkol, A.; Kittipongphat, P.; Trachoo, V.; Osathanon, T.; Aimmanee, S.; Everts, V.; Samaranayake, L.; et al. Lesion Morphology Modification Is Unnecessary for Non-Carious Cervical Lesion Restorations: A Comparison of Stiff and Flowable Composites. Int. Dent. J. 2026, 76, 109284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, D.W.; Shah, P. A Critical Review of Non-Carious Cervical (Wear) Lesions and the Role of Abfraction, Erosion, and Abrasion. J. Dent. Res. 2006, 85, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; Kubo, S.; Pereira, P.N.R.; Ikeda, M.; Takagaki, T.; Nikaido, T.; Tagami, J. Progression of Non-Carious Cervical Lesions: 3D Morphological Analysis. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2022, 26, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peumans, M.; Politano, G.; Van Meerbeek, B. Treatment of Noncarious Cervical Lesions: When, Why, and How. Int. J. Esthet. Dent. 2020, 15, 16–42. [Google Scholar]

- Shetty, S.M.; Shetty, R.G.; Mattigatti, S.; Managoli, N.A.; Rairam, S.G.; Patil, A.M. No Carious Cervical Lesions: Abfraction. J. Int. Oral. Health 2013, 5, 143–146. [Google Scholar]

- Brackett, W.; Brackett, M.; Pacheco, R.; Dudish, C.; Beatty, M. Restoration of Non-Carious Cervical Lesions: A Brief Review for Clinicians. Oper. Dent. 2024, 49, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.-K.; Wu, J.-H.; Chen, P.-H.; Ho, P.-S.; Chen, K.-K. Influence of Cavity Depth and Restoration of Non-Carious Cervical Root Lesions on Strain Distribution from Various Loading Sites. BMC Oral. Health 2020, 20, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, C.; Kress, E.; Götz, H.; Taylor, K.; Willershausen, I.; Zampelis, A. The Anatomy of Non-Carious Cervical Lesions. Clin. Oral. Investig 2014, 18, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-din, A.K.N.; Miller, B.H.; Griggs, J.A. Resin Bonding to Sclerotic, Noncarious, Cervical Lesions. Quintessence Int. 2004, 35, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karan, K.; Yao, X.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y. Chemical Profile of the Dentin Substrate in Non-Carious Cervical Lesions. Dental. Mater. 2009, 25, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, T.C.; Lepe, X.; Johnson, G.H.; Mancl, L. Characteristics of Noncarious Cervical Lesions. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2002, 133, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkilic, E.E.; Omurlu, H. Two-Year Clinical Evaluation of Three Adhesive Systems in Non-Carious Cervical Lesions. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2012, 20, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, F.R.; Pashley, D.H. Resin Bonding to Cervical Sclerotic Dentin: A Review. J. Dent. 2004, 32, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senawongse, P.; Srihanon, A.; Muangmingsuk, A.; Harnirattisai, C. Effect of Dentine Smear Layer on the Performance of Self-etching Adhesive Systems: A Micro-tensile Bond Strength Study. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2010, 94B, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meerbeek, B.; Braem, M.; Lambrechts, P.; Vanherle, G. Morphological Characterization of the Interface between Resin and Sclerotic Dentine. J. Dent. 1994, 22, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodacre, C.J.; Eugene Roberts, W.; Munoz, C.A. Noncarious Cervical Lesions: Morphology and Progression, Prevalence, Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Guidelines for Restoration. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 32, E1–E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurer, J.C.; Rizzante, F.A.P.; Maenossono, R.M.; França, F.M.G.; Bombonatti, J.F.S.; Ishikiriama, S.K. Effect of Cavosurface Angle Beveling on the Exposure Angle of Enamel Prisms in Different Cavity Sizes. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2020, 83, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baratieri, L.N.; Canabarro, S.; Lopes, G.C.; Ritter, A. V Effect of Resin Viscosity and Enamel Beveling on the Clinical Performance of Class V Composite Restorations: Three-Year Results. Oper. Dent. 2003, 28, 482–487. [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa, T.R.F.; Loguercio, A.D.; Reis, A. Effect of Enamel Bevel on the Clinical Performance of Resin Composite Restorations Placed in Non-carious Cervical Lesions. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2013, 25, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, M.; Reis, A.; Luque-Martinez, I.; Loguercio, A.D.; Masterson, D.; Maia, L.C. Effect of Enamel Bevel on Retention of Cervical Composite Resin Restorations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Dent. 2015, 43, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedeljkovic, I.; De Munck, J.; Vanloy, A.; Declerck, D.; Lambrechts, P.; Peumans, M.; Teughels, W.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Van Landuyt, K.L. Secondary Caries: Prevalence, Characteristics, and Approach. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2020, 24, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilcher, L.; Pahlke, S.; Urquhart, O.; O’Brien, K.K.; Dhar, V.; Fontana, M.; González-Cabezas, C.; Keels, M.A.; Mascarenhas, A.K.; Nascimento, M.M.; et al. Direct Materials for Restoring Caries Lesions. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2023, 154, e1–e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, V.; Pilcher, L.; Fontana, M.; González-Cabezas, C.; Keels, M.A.; Mascarenhas, A.K.; Nascimento, M.; Platt, J.A.; Sabino, G.J.; Slayton, R.; et al. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline on Restorative Treatments for Caries Lesions. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2023, 154, 551–566.e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campolina, M.G.; de Souza, P.A.; Dietrich, L.; Soares, C.J.; Carvalho, C.N.; Carlo, H.L.; Silva, G.R. Can Charcoal-Based Dentifrices Change the Color Stability and Roughness of Bleached Tooth Enamel and Resin Composites? J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2025, 17, e149–e159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagman, S.S. The Role of Coronal Contour in Gingival Health. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1977, 37, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachetti, L. A Simple Method for Modifying the Emergence Profile by Direct Restorations: The Biologically Active Intrasulcular Restoration Technique. Oper. Dent. 2020, 45, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennis, W.M.M.; Kuijs, R.H.; Barink, M.; Kreulen, C.M.; Verdonschot, N.; Creugers, N.H.J. Can Internal Stresses Explain the Fracture Resistance of Cusp-replacing Composite Restorations? Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 2005, 113, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peumans, M.; De Munck, J.; Van Landuyt, K.L.; Poitevin, A.; Lambrechts, P.; Van Meerbeek, B. A 13-Year Clinical Evaluation of Two Three-Step Etch-and-Rinse Adhesives in Non-Carious Class-V Lesions. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2012, 16, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, J.S.; Jacobsen, P.H. The Effect of Cuspal Flexure on a Buccal Class V Restoration: A Finite Element Study. J. Dent. 1998, 26, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymann, H.O.; Sturdevant, J.R.; Bayne, S.; Wilder, A.D.; Sluder, T.B.; Brunson, W.D. Examining Tooth Flexure Effects on Cervical Restorations: A Two-Year Clinical Study. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1991, 122, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Yang, X.; Wong, M.C.; Zou, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, C.; Wang, Y. Rubber Dam Isolation for Restorative Treatment in Dental Patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2021, CD009858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favetti, M.; Montagner, A.F.; Fontes, S.T.; Martins, T.M.; Masotti, A.S.; Jardim, P.d.S.; Corrêa, F.O.B.; Cenci, M.S.; Muniz, F.W.M.G. Effects of Cervical Restorations on the Periodontal Tissues: 5-Year Follow-up Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Dent. 2021, 106, 103571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahr, A.; Schön, F.; Haller, B. Effect of Gingival Fluid on Marginal Adaptation of Class II Resin-Based Composite Restorations. Am. J. Dent. 2000, 13, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bonchev, A. Clinical Management of Cervical Restorations with Closing Gap Technique: A Follow-Up of Two Cases. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010013

Bonchev A. Clinical Management of Cervical Restorations with Closing Gap Technique: A Follow-Up of Two Cases. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonchev, Alexander. 2026. "Clinical Management of Cervical Restorations with Closing Gap Technique: A Follow-Up of Two Cases" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010013

APA StyleBonchev, A. (2026). Clinical Management of Cervical Restorations with Closing Gap Technique: A Follow-Up of Two Cases. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010013