A Survey of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life for Adults with Cerebral Palsy in Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethics

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

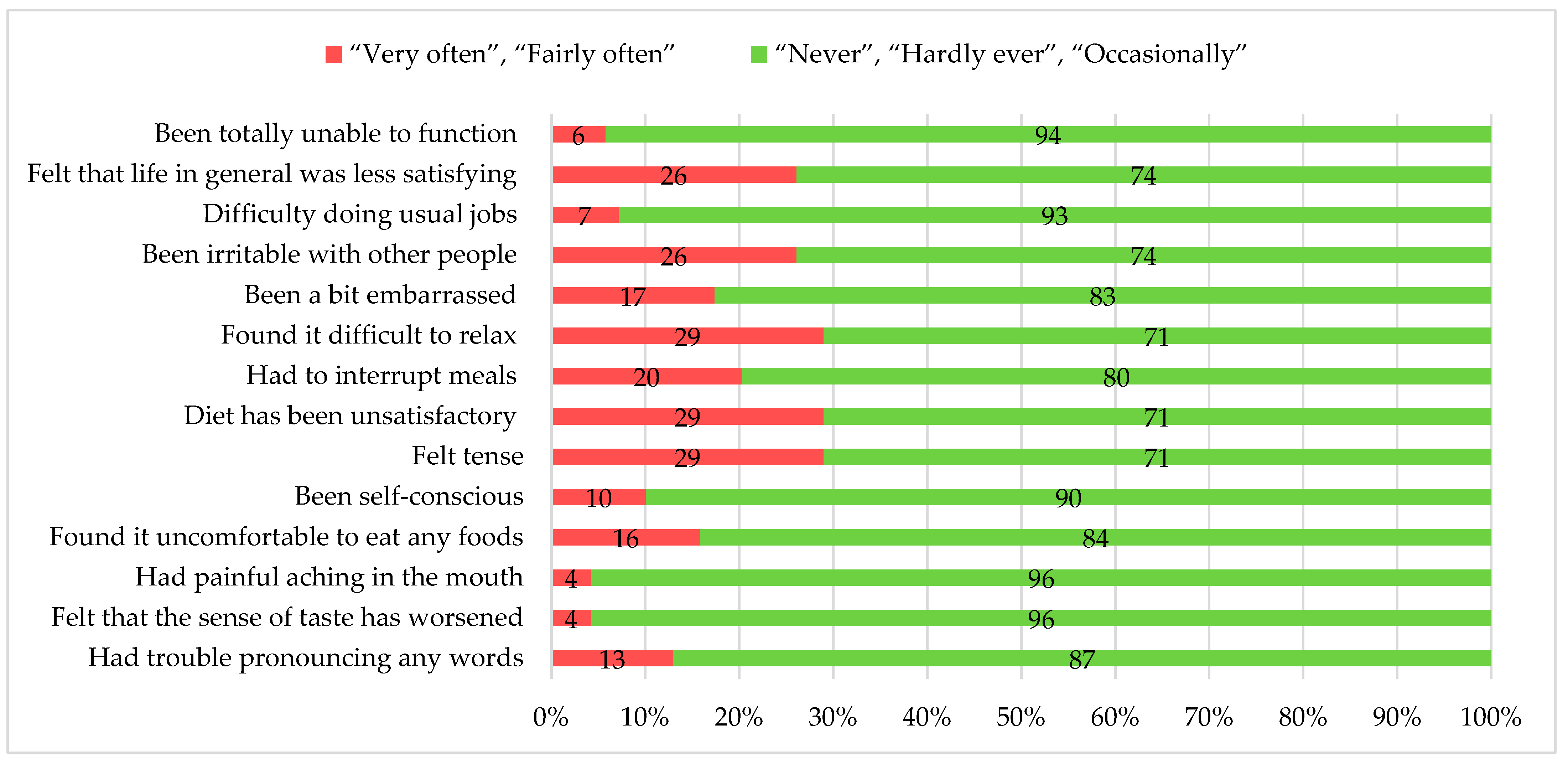

3. Results

Dental Care Experiences

4. Discussion

Recommendations for Improving OHRQoL for Adults with CP

- Prioritize timely dental care for people with CP utilizing multidisciplinary and patient-centered approaches.

- Consider functional abilities (in particular MACS, CFCS, and VSS) when developing oral health care plans.

- Develop structured referral frameworks that promote equitable access to dental care for people with CP.

- Educate dental professionals in disability inclusive practices to enhance patient comfort and quality of care.

- Improve access to dental care, such as access to home and community-based care, mobile clinics, and telehealth, to enhance dental access for people with CP.

- Undertake further research to better understand the sociodemographic and geographical factors that affect access to dental care for people with CP. These findings should then be used to inform evidence-based policy, practices, and dental education programs.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OHRQoL | Oral Health-Related Quality of Life |

| CP | Cerebral Palsy |

| OHIP-14 | Oral Health Impact Profile-14 |

| REDCap | Research Electronic Data Capture |

| SEIFA | Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas |

| GMFCS | Gross Motor Function Classification System |

| MACS | Manual Ability Classification System |

| VSS | Viking Speech Scale |

| CFCS | Communication Function Classification System |

| MWU | Mann–Whitney U test |

| KWH | Kruskal–Wallis H test |

| CROSS | Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies |

| OHIP | Oral Health Impact |

References

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax, M.; Damiano, D.; Dan, B.; Jacobsson, B. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. Suppl. 2007, 109, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavone, P.; Gulizia, C.; Le Pira, A.; Greco, F.; Parisi, P.; Di Cara, G.; Falsaperla, R.; Lubrano, R.; Minardi, C.; Spalice, A.; et al. Cerebral Palsy and Epilepsy in Children: Clinical Perspectives on a Common Comorbidity. Children 2020, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twum, F.; Hayford, J.K. Motor Development in Cerebral Palsy and Its Relationship to Intellectual Development: A Review Article. Eur. J. Med. Health Sci. 2024, 6, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolman, S.E.; Glanzman, A.M.; Prosser, L.; Spiegel, D.A.; Baldwin, K.D. Factors that Predict Overall Health and Quality of Life in Non-Ambulatory Individuals with Cerebral Palsy. Iowa Orthop. J. 2018, 38, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiang, B.; Walstab, J.; Reid, S.M.; Davis, E.; Reddihough, D. Quality of life in young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Health J. 2016, 9, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484 (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Palanisamy, S.; Cholan, P.; Ramachandran, L.; Tadepalli, A.; Parthasarsthy, H.; Umesh, S.G. Navigating Oral Hygiene Challenges in Spastic Cerebral Palsy Patients. A Narrative Review for Management Strategies for Optimal Dental Care. Cureus 2023, 15, e50246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, T.N.; Drumond, V.Z.; de Arruda, J.A.A.; Pani, S.C.; Vargas-Ferreira, F.; Eustachio, R.R.; Mesquita, R.A.; Abreu, L.G. Dental caries and developmental defects of enamel in cerebral palsy. A meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 3828–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, F.Y.I.; Tennant, M.; Kruger, E. Oral health of individuals with cerebral palsy in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2024, 52, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansdown, K.; Irving, M.; Mathieu Coulton, K.; Smithers-Sheedy, H. A scoping review of oral health outcomes for people with cerebral palsy. Spec. Care Dent. 2022, 42, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sischo, L.; Broder, H.L. Oral health-related quality of life: What, why, how, and future implications. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commonwealth of Australia. Select Committee into the Provision of and Access to Dental Services in Australia: A System in Decay: A Review into Dental Services in Australia—Final Report. Canberra. 2023. Available online: https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/reportsen/RB000078/toc_pdf/AsystemindecayareviewintodentalservicesinAustralia.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Remoteness Areas. Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) Edition 3 Reference period July 2021–June 2026. Map of ASGS Edition 3 Remoteness Areas for Australia. 2023. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/australian-statistical-geography-standard-asgs-edition-3/jul2021-jun2026/remoteness-structure/remoteness-areas (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA): Postal Areas, Indexes, SEIFA 2016 Postal Areas, 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/2033.0.55.0012016?OpenDocument (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Palisano, R.; Rosenbaum, P.; Walter, S.; Russell, D.; Wood, E.; Galuppi, B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1997, 39, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, A.C.; Krumlinde-Sundholm, L.; Rösblad, B.; Beckung, E.; Arner, M.; Öhrvall, A.-M.; Rosenbaum, P. The Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) for children with cerebral palsy: Scale development and evidence of validity and reliability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2006, 48, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, L.; Virella, D.; Mjøen, T.; da Graça Andrada, M.; Murray, J.; Colver, A.; Himmelmann, K.; Rackauskaite, G.; Greitane, A.; Prasauskiene, A.; et al. Development of The Viking Speech Scale to classify the speech of children with cerebral palsy. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 3202–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidecker, M.J.; Paneth, N.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Kent, R.D.; Lillie, J.; Eulenberg, J.B.; Chester, K.; Johnson, B.; Michalsen, L.; Evatt, M.; et al. Developing and validating the Communication Function Classification System for individuals with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2011, 53, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, G.D. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1997, 25, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Drake, M.; Kruger, E.; Tennant, M. Determining The Barriers to Access Dental Services For People with A Disability: A qualitative study. Asia Pac. J. Health Manag. 2022, 17, i35. Available online: https://journal.achsm.org.au/index.php/achsm/article/view/815 (accessed on 13 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0.2.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023.

- Arifin, W.N. A Web-based Sample Size Calculator for Reliability Studies. Educ. Med. J. 2018, 10, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broder, H.L.; Wilson-Genderson, M. Reliability and convergent and discriminant validity of the Child Oral Health Impact Profile (COHIP Child’s version). Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannopoulou, V.; Oulis, C.J.; Papaioannou, W.; Antonogeorgos, G.; Yfantopoulos, J. Validation of a Greek version of the oral health impact profile (OHIP-14) for use among adults. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Minh Duc, N.T.; Luu Lam Thang, T.; Nam, N.H.; Ng, S.J.; Abbas, K.S.; Huy, N.T.; Marušić, A.; Paul, C.L.; Kwok, J.; et al. A Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS). J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 3179–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzar, M.A.; Kahwagi, E.; Yamakawa, T. Investigating oral health-related quality of life and self-perceived satisfaction with partial dentures. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2012, 3, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, G.C.; Elani, H.W.; Harper, S.; Thomson, W.M.; Ju, X.; Kawachi, I.; Kaufman, J.S.; Jamieson, L.M. Socioeconomic status, oral health and dental disease in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, Y.R.; Choi, J.Y.; Kim, S.A.; Park, J.; Park, E.S. Comparisons of severity classification systems for oropharyngeal dysfunction in children with cerebral palsy: Relations with other functional profiles. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 72, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speyer, R.; Cordier, R.; Kim, J.H.; Cocks, N.; Michou, E.; Wilkes-Gillan, S. Prevalence of drooling, swallowing, and feeding problems in cerebral palsy across the lifespan: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansdown, K.; Bulkeley, K.; McGrath, M.; Irving, M.; Zagreanu, C.; Smithers-Sheedy, H. Dental care and services of children and young people with cerebral palsy in Australia: A comprehensive survey of oral health-related quality of life. Spec. Care Dentist. 2025, 45, e13098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Faiz, M.N.; Abd Rahman, M.S.H.; Nurazfalina, A.A.A.; Jennifer, T.; Nabil, S.; Tan, J.K.; Tan, H.J. Oral health assessment of epilepsy patients from a tertiary hospital in Asia. Med. J. Malays. 2024, 79, 443–451. Available online: https://www.e-mjm.org/2024/v79n4/oral-health.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Kim, S. Navigating the healthcare system as an adult with cerebral palsy: A call for change. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2024, 67, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Harris, I.; Lu, Z.K. Differences in proxy-reported and patient-reported outcomes: Assessing health and functional status among medicare beneficiaries. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, C.; Khadka, J.; Crocker, M.; Lay, K.; Milte, R.; Whitehirst, D.G.T.; Engel, L.; Ratcliffe, J. Examining interrater agreement between self-report and proxy-report responses for the quality of life-aged care consumers (QOL-ACC) instrument. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2024, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, M.T.; Omara, M.; Su, N.; List, T.; Sekulic, S.; Häggman-Henrikson, B.; Visscher, C.M.; Bekes, K.; Reissmann, D.R.; Baba, K.; et al. Recommendations for use and scoring of Oral Health Impact Profile versions. J. Evid.-Based Dent. Pract. 2022, 22, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | n | % | |

| Age group | 18–25 years | 29 | 42.0 |

| 26-35 years | 17 | 24.6 | |

| 36-45 years | 16 | 23.2 | |

| 46-55 years | 4 | 5.8 | |

| over 55 years | 3 | 4.3 | |

| Gender | Males | 35 | 50.7 |

| Females | 34 | 49.3 | |

| Self-report | 22 | 31.9 | |

| Proxy-report | 47 | 68.1 | |

| Country of birth | Not stated | 1 | 1.4 |

| Australia | 65 | 94.2 | |

| Overseas | 3 | 4.3 | |

| Remoteness (Australia) | Not stated | 2 | 2.9 |

| Major cities | 52 | 75.4 | |

| Inner regional | 11 | 15.9 | |

| Outer regional | 4 | 5.8 | |

| SEIFA | Not stated | 2 | 2.9 |

| Quintile 1 | 8 | 11.6 | |

| Quintile 2 | 13 | 18.8 | |

| Quintile 3 | 9 | 13.0 | |

| Quintile 4 | 15 | 21.7 | |

| Quintile 5 | 22 | 31.9 | |

| CP motor type | Not stated | 11 | 15.9 |

| Ataxic | 7 | 10.1 | |

| Spastic | 46 | 66.7 | |

| Dyskinetic | 5 | 7.2 | |

| Unilateral | 16 | 34.8 | |

| Bilateral | 30 | 65.2 | |

| GMFCS scale | Levels I-II | 23 | 33.3 |

| Levels III-V | 46 | 66.7 | |

| MACS scale | Levels I-II | 20 | 29.0 |

| Levels III-V | 49 | 71.0 | |

| VSS scale | Levels I-II | 36 | 52.2 |

| Levels III-IV | 33 | 47.8 | |

| CFCS | Levels I-II | 46 | 66.7 |

| Levels III-IV | 23 | 33.3 | |

| Hearing | Bilateral deafness | 4 | 5.8 |

| No impairment | 56 | 81.2 | |

| Some impairment | 9 | 13.0 | |

| Epilepsy | Yes | 33 | 47.8 |

| Anti-seizure medication | Yes | 28 | 40.6 |

| Scale item | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted |

| OHIP-14—Trouble pronouncing any words | 0.599 | 0.896 |

| OHIP-14—Worse sense of taste | 0.591 | 0.895 |

| OHIP-14—Painful aching in the mouth | 0.387 | 0.902 |

| OHIP-14—Uncomfortable to eat any foods | 0.710 | 0.890 |

| OHIP-14—Been self-conscious | 0.642 | 0.893 |

| OHIP-14—Felt tense | 0.543 | 0.897 |

| OHIP-14—Unsatisfactory diet | 0.720 | 0.889 |

| OHIP-14—Interrupted meals | 0.735 | 0.889 |

| OHIP-14—Difficult to relax | 0.700 | 0.890 |

| OHIP-14—Been embarrassed | 0.530 | 0.897 |

| OHIP-14—Been irritable with other people | 0.618 | 0.894 |

| OHIP-14—Difficulty doing usual jobs | 0.425 | 0.901 |

| OHIP-14—Felt that life in general was less satisfying | 0.666 | 0.892 |

| OHIP-14—Been totally unable to function | 0.504 | 0.899 |

| Dimensions | Oral health daily routine | rs | p-value | ||

| “Fairly straightforward” n = 21 Mean ± SD | “A bit of a challenge” n = 37 Mean ± SD | “Extremely difficult” n = 11 Mean ± SD | |||

| Functional limitation | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 2.1 | 2.6 ± 2.1 | 0.358 | 0.003 |

| Physical pain | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 2.4 ± 1.8 | 3.0 ± 1.4 | 0.336 | 0.005 |

| Psychological discomfort | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 1.7 ± 2.0 | 1.8 ± 1.9 | 0.142 | 0.245 |

| Physical disability | 0.5 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 0.375 | 0.002 |

| Psychological disability | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 0.327 | 0.006 |

| Social disability | 0.4 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 2.0 ± 2.1 | 0.327 | 0.006 |

| Handicap | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 1.1 ± 1.4 | 0.171 | 0.159 |

| OHIP-14 | 6.0 ± 6.6 | 11.3 ± 9.8 | 15.5 ± 9.5 | 0.360 | 0.002 |

| Variable | n | OHIP-14 scale total score | Functional limitation dimension | Physical pain dimension | Psychological discomfort dimension | Physical disability dimension | Psychological disability dimension | Social disability dimension | Handicap dimension | ||||||||||||||||

| Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | ||

| Age group | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18–25 years | 29 | 11.0 ± 10.5 | 9.5 | 0.527 (KWH) | 1.4 ± 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.081 (KWH) | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.255 (KWH) | 1.9 ± 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.064 (KWH) | 1.7 ± 2.1 | 1.0 | 0.321 (KWH) | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.517 (KWH) | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.886 (KWH) | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.183 (KWH) |

| 26–35 years | 17 | 10.5 ± 9.2 | 7.0 | 2.3 ± 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.6 ± 1.9 | 3.0 | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.0 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.1 ± 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| 36–45 years | 16 | 4.5 ± 5.2 | 6.5 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.0 | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 ± 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.0 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.9 ± 1.0 | 0.5 | ||||||||

| 46–55 years | 4 | 4.5 ± 5.25 | 3.0 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.2 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.7 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 0.5 | ||||||||

| Over 55 years | 3 | 16.0 ± 6.0 | 13.0 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.0 | 4.0 ± 0.0 | 4.0 | 2.6 ± 2.5 | 3.0 | 1.6 ± 1.1 | 1.0 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 3.0 | ||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Males | 35 | 10.6 ± 9.2 | 7.0 | 0.673 (MWU) | 1.7 ± 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.100 (MWU) | 2.1 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.526 (MWU) | 1.7 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.299 (MWU) | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.689 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.438 (MWU) | 0.9 ± 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.766 (MWU) | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.942 (MWU) |

| Females | 34 | 10.6 ± 9.6 | 7.0 | 1.3 ± 2.1 | 0.0 | 2.4 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Survey responses | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Self-report | 22 | 9.0 ± 7.7 | 7.0 | 0.557 (MWU) | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.020 (MWU) | 2.2 ± 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.999 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 2.1 | 0.5 | 0.973 (MWU) | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.086 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 1.7 | 1.5 | 0.604 (MWU) | 0.9 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.486 (MWU) | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.798 (MWU) |

| Proxy-report | 47 | 11.0 ± 10.0 | 7.0 | 1.9 ± 2.1 | 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.7 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Remoteness (Australia) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Major Cities | 52 | 10.6 ± 10.0 | 7.0 | 0.812 (KWH) | 1.7 ± 2.1 | 1.0 | 0.251 (KWH) | 2.2 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.764 (KWH) | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.180 (KWH) | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.551 (KWH) | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.560 (KWH) | 1.1 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.244 (KWH) | 1.1 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.493 (KWH) |

| Inner Regional | 11 | 10.0 ± 8.1 | 8.0 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 0.0 | 2.5 ± 1.8 | 3.0 | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Outer Regional | 4 | 6.0 ± 4.0 | 6.0 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.7 ± 1.7 | 1.5 | 2.0 ± 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 ± 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| SEIFA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quintile 1 | 8 | 13.8 ± 8.3 | 12.0 | 0.373 (KWH) | 2.1 ± 2.4 | 1.5 | 0.758 (KWH) | 2.3 ± 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.945 (KWH) | 2.3 ± 2.4 | 2.0 | 0.432 (KWH) | 1.8 ± 1.6 | 2.0 | 0.459 (KWH) | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 2.0 | 0.076 (KWH) | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.977 (KWH) | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.040 (KWH) |

| Quintile 2 | 13 | 8.3 ± 8.8 | 6.0 | 1.3 ± 1.9 | 0.0 | 2.2 ± 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.2 ± 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.9 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Quintile 3 | 9 | 13.2 ± 9.2 | 15.0 | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.6 ± 1.7 | 3.0 | 2.1 ± 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.3 ± 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.3 ± 1.9 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Quintile 4 | 15 | 10.3 ± 8.7 | 7.0 | 1.4 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.6 | 3.0 | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.4 ± 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.2 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.2 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Quintile 5 | 22 | 8.8 ± 10.9 | 3.5 | 1.5 ± 2.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.0 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.1 ± 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 1.0 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.0 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Type of CP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Not stated | 11 | 10.9 ± 9.4 | 11.0 | 0.892 (KWH) | 2.1 ± 2.3 | 1.0 | 0.634 (KWH) | 1.9 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.776 (KWH) | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.623 (KWH) | 2.1 ± 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.336 (KWH) | 0.9 ± 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.877 (KWH) | 1.1 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.872 (KWH) | 1.1 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.821 (KWH) |

| Ataxic | 7 | 7.5 ± 6.2 | 11.0 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 2.0 | 1.0 ± 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 0.0 | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Dyskinetic | 5 | 12.4 ± 15.6 | 2.0 | 2.4 ± 3.3 | 0.0 | 2.4 ± 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 ± 2.8 | 0.0 | 2.0 ± 3.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 ± 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.8 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.8 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Spastic | 46 | 10.6 ± 9.2 | 7.0 | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 1.0 | 2.4 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.7 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 0.5 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Unilateral | 16 | 10.8 ± 9.1 | 9.5 | 0.999 (MWU) | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.800 (MWU) | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.223 (MWU) | 2.1 ± 2.5 | 1.0 | 0.773 (MWU) | 1.2 ± 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.795 (MWU) | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 2.0 | 0.291 (MWU) | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.393 (MWU) | 1.3 ± 1.3 | 2.0 | 0.282 (MWU) |

| Bilateral | 30 | 10.5 ±9.3 | 7.0 | 1.4 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.6 ± 1.8 | 2.5 | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.4 ± 1.3 | 0.5 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 0.5 | 1.2 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.9 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| GMFCS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Levels I-II | 23 | 8.7 ± 9.0 | 6.0 | 0.199 (MWU) | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.166 (MWU) | 1.7 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.037 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 2.1 | 1.0 | 0.979 (MWU) | 1.0 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.324 (MWU) | 1.3 ± 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.936 (MWU) | 0.8 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.430 (MWU) | 0.8 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.944 (MWU) |

| Levels III-V | 46 | 11.1 ± 9.5 | 8.0 | 1.7 ± 2.1 | 1.0 | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 2.0 | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| MACS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Levels I-II | 18 | 3.7 ± 4.6 | 1.5 | <0.001 (MWU) | 0.8 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.015 (MWU) | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.009 (MWU) | 0.7 ± 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.037 (MWU) | 0.8 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.058 (MWU) | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.013 (MWU) | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.053 (MWU) | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.114 (MWU) |

| Levels III-V | 49 | 12.2 ± 9.5 | 12.0 | 1.8 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.6 ± 1.7 | 3.0 | 1.9 ± 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.7 ± 1.6 | 2.0 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| VSS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Levels I-II | 36 | 8.4 ± 7.8 | 6.5 | 0.123 (MWU) | 0.9 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.024 (MWU) | 2.0 ± 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.222 (MWU) | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.909 (MWU) | 0.9 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.062 (MWU) | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.472 (MWU) | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.196 (MWU) | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.439 (MWU) |

| Levels III-IV | 33 | 12.4 ± 10.5 | 12.0 | 2.2 ± 2.3 | 1.0 | 2.5 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.9 ± 2.1 | 1.0 | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| CFCS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Levels I-II | 46 | 9.4 ± 8.6 | 6.5 | 0.319 (MWU) | 1.1 ± 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.109 (MWU) | 2.2 ± 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.826 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.846 (MWU) | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.033 (MWU) | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.957 (MWU) | 0.9 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.322 (MWU) | 0.9 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.916 (MWU) |

| Levels III-V | 23 | 12.2 ± 10.6 | 11.0 | 2.3 ± 2.6 | 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.1 ± 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Hearing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No impairment | 56 | 10.1 ± 9.6 | 7.0 | 0.714 (KWH) | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.307 (KWH) | 2.1 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.465 (KWH) | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.793 (KWH) | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.646 (KWH) | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.532 (KWH) | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.657 (KWH) | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.819 (KWH) |

| Some impairment | 9 | 10.5 ± 9.1 | 11.0 | 1.5 ± 2.4 | 0.0 | 2.6 ± 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.4 ± 1.3 | 2.0 | 0.8 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.8 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Bilateral deafness | 4 | 13.0 ± 8.2 | 14.5 | 3.2 ± 2.7 | 3.5 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 3.0 | 1.5 ± 3.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.2 ± 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Epilepsy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 33 | 11.9 ± 10.3 | 11.0 | 0.252 (MWU) | 2.1 ± 2.3 | 1.0 | 0.040 (MWU) | 2.5 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.308 (MWU) | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.874 (MWU) | 1.9 ± 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.129 (MWU) | 1.3 ± 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.799 (MWU) | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.123 (MWU) | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.947 (MWU) |

| No | 36 | 8.9 ± 8.2 | 7.0 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | 2.0 ± 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 ± 2.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 ± 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Anti-seizure medication | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 28 | 13.2 ± 10.7 | 12.5 | 0.129 (MWU) | 2.3 ± 2.3 | 2.0 | 0.104 (MWU) | 2.5 ± 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.981 (MWU) | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.715 (MWU) | 2.3 ± 2.2 | 2.5 | 0.030 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 1.4 | 2.0 | 0.034 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.045 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.058 (MWU) |

| No | 5 | 4.4 ± 2.8 | 6.0 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 0.0 | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 3.0 | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Variable | n | % |

| Is your daily routine of teeth cleaning? | ||

| Fairly straightforward | 21 | 30.4 |

| A bit of a challenge | 37 | 53.6 |

| Extremely difficult | 11 | 15.9 |

| Do you have a regular dentist? | ||

| My whole family uses the same dentist. | 33 | 47.8 |

| I have my own dentist or more than one dentist. | 13 | 18.8 |

| Different family members in my family have different dentists. | 5 | 7.2 |

| I do not have a dentist. | 18 | 26.1 |

| Does cerebral palsy affect your capacity to participate in dental examinations and treatment? | ||

| Yes | 44 | 63.8 |

| If you have previously accessed dental treatment, e.g., exam, filling, cap/crown etc. Please select all that apply. | ||

| Simple dental check-up clean, no special requirements needed. | 33 | 47.8 |

| Special arrangements were needed to attend the local practice | 17 | 23.5 |

| Some sedation was needed at the general dentist. | 8 | 11.6 |

| Dental treatment needed to be performed at a day surgery/hospital. | 25 | 36.2 |

| Never accessed dental treatment. | 3 | 4.3 |

| Have you ever had a dental professional (including Dental Hygienist, Dental Therapist, Oral Health Therapist or Dentist) come to your home for examination or treatment? | ||

| Yes | 2 | 2.9 |

| Have you had to find urgent dental care due to pain or another problem(s)? | ||

| Yes | 17 | 24.6 |

| Have you required complex dental surgery? On what basis has the complex surgery been provided? | ||

| Emergency | 3 | 4.3 |

| Planned | 22 | 31.9 |

| Emergency and planned | 4 | 5.8 |

| Not applicable | 40 | 58.0 |

| If you needed complex dental surgery, how were the arrangements made? | ||

| I made the arrangements | 21 | 30.4 |

| I was given assistance by another medical/dental practitioner. | 9 | 13.0 |

| Not applicable | 39 | 56.5 |

| Variable | n | OHIP-14 scale total score | Functional limitation dimension | Physical pain dimension | Psychological discomfort dimension | Physical disability dimension | Psychological disability dimension | Social disability dimension | Handicap dimension | ||||||||||||||||

| Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | Mean ± SD | Median | p-value | ||

| Is your daily routine of teeth cleaning? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fairly straightforward | 21 | 6.0 ± 6.6 | 4.0 | 0.012 (KWH) | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.013 (KWH) | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.021 (KWH) | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.482 (KWH) | 0.5 ± 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.007 (KWH) | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.297 (KWH) | 0.4 ± 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.026 (KWH) | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.302 (KWH) |

| A bit of a challenge | 37 | 11.3 ± 9.8 | 8.0 | 1.7 ± 2.1 | 1.0 | 2.4 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.7 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Extremely difficult | 11 | 15.5 ± 9.5 | 16.0 | 2.6 ± 2.1 | 2.0 | 3.0 ± 1.4 | 3.0 | 1.8 ± 1.9 | 2.0 | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 3.0 | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 ± 2.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.4 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Do you have a regular dentist? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| My whole family uses the same dentist. | 13 | 9.3 ± 9.5 | 6.0 | 0.784 (KWH) | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.885 (KWH) | 1.8 ± 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.317 (KWH) | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.542 (KWH) | 1.2 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.885 (KWH) | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.984 (KWH) | 1.0 ± 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.932 (KWH) | 0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.651 (KWH) |

| I have my own dentist or more than one dentist. | 33 | 9.9 ± 9.6 | 6.0 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.4 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 1.1 ± 1.3 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Different family members in my family have different dentists. | 5 | 12.6 ± 9.6 | 13.0 | 2.0 ± 2.3 | 1.0 | 3.2 ± 1.9 | 4.0 | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.2 ± 2.1 | 0.0 | 1.6 ± 1.6 | 2.0 | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| I do not have a dentist. | 18 | 11.2 ± 9.2 | 9.0 | 1.6 ± 2.3 | 0.5 | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.9 ± 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 0.5 | 1.5 ± 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.8 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Does cerebral palsy affect your capacity to participate in dental examinations and treatment? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 44 | 11.1 ± 10.1 | 7.5 | 0.511 (MWU) | 1.9 ± 2.1 | 1.5 | 0.069 (MWU) | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.284 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.927 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.320 (MWU) | 1.4 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.884 (MWU) | 1.1 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.910 (MWU) | 0.9 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.271 (MWU) |

| No | 25 | 9.0 ± 7.9 | 7.0 | 0.8 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.9 ± 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.1 ± 1.2 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| If you have previously accessed dental treatment, e.g., exam, filling, cap/crown etc. Please select all that apply. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simple dental check-up clean, no special requirements needed. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 33 | 7.7 ± 8.5 | 4.0 | 0.017 (MWU) | 0.8 ± 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.007 (MWU) | 1.8 ± 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.039 (MWU) | 1.3 ± 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.179 (MWU) | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.006 (MWU) | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.343 (MWU) | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.138 (MWU) | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.090 (MWU) |

| No | 36 | 12.7 ± 9.6 | 11.5 | 2.1 ± 2.2 | 1.5 | 2.6 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.7 ± 1.8 | 1.5 | 2.0 ± 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 ± 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.2 ± 1.6 | 0.5 | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Special arrangements were needed to attend the local practice | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 17 | 7.8 ± 9.6 | 4.0 | 0.144 (MWU) | 1.0 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.174 (MWU) | 2.1 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.810 (MWU) | 1.2 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.329 (MWU) | 1.0 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.182 (MWU) | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.244 (MWU) | 0.7 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.180 (MWU) | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.034 (MWU) |

| No | 52 | 11.1 ± 9.2 | 11.0 | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.7 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.5 ± 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.2 ± 1.3 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Some sedation was needed at the general dentist. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 8 | 11.3 ± 10.6 | 9.5 | 0.807 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 2.1 | 1.0 | 0.976 (MWU) | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 2.5 | 0.505 (MWU) | 1.5 ± 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.812 (MWU) | 1.7 ± 2.1 | 0.5 | 0.664 (MWU) | 1.7 ± 1.6 | 2.0 | 0.512 (MWU) | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.792 (MWU) | 1.2 ± 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.796 (MWU) |

| No | 61 | 10.2 ± 9.3 | 7.0 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Dental treatment needed to be performed at a day surgery/hospital. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 25 | 11.6 ± 9.9 | 7.0 | 0.213 (MWU) | 2.0 ± 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.052 (MWU) | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 2.0 | 0.161 (MWU) | 2.0 ± 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.096 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 2.1 | 1.0 | 0.502 (MWU) | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.526 (MWU) | 1.0 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.482 (MWU) | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.978 (MWU) |

| No | 44 | 9.4 ± 9.0 | 7.5 | 1.2 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 2.0 ± 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Never accessed dental treatment. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 3 | 10.0 ± 16.4 | 1.0 | 0.585 (MWU) | 2.6 ± 4.6 | 0.0 | 0.901 (MWU) | 2.3 ± 3.2 | 1.0 | 0.857 (MWU) | 2.0 ± 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.879 (MWU) | 1.6 ± 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.945 (MWU) | 1.3 ± 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.771 (MWU) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.235 (MWU) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.181 (MWU) |

| No | 66 | 10.3 ± 9.1 | 7.5 | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 0.5 | 1.4 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Have you ever had a dental professional (including Dental Hygienist, Dental Therapist, Oral Health Therapist or Dentist) come to your home for examination or treatment? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 2 | 12.5 ± 17.6 | 12.5 | 0.986 (MWU) | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.819 (MWU) | 1.5 ± 2.1 | 1.5 | 0.554 (MWU) | 3.0 ± 4.2 | 3.0 | 0.668 (MWU) | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.846 (MWU) | 2.0 ± 2.8 | 2.0 | 0.793 (MWU) | 2.5 ± 3.5 | 2.5 | 0.533 (MWU) | 1.5 ± 2.1 | 1.5 | 0.692 (MWU) |

| No | 67 | 10.3 ± 9.2 | 7.0 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.4 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Have you had to find urgent dental care due to pain or another problem(s)? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 17 | 10.2 ± 8.5 | 11.0 | 0.889 (MWU) | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.872 (MWU) | 2.2 ± 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.932 (MWU) | 1.8 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.463 (MWU) | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.782 (MWU) | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.836 (MWU) | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.371 (MWU) | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.713 (MWU) |

| No | 52 | 10.3 ± 9.7 | 7.0 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.4 ± 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.9 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Have you required complex dental surgery? On what basis has the complex surgery been provided? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emergency | 3 | 10.6 ± 12.8 | 7.0 | 0.971 (KWH) | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 2.0 | 0.589 (KWH) | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.775 (KWH) | 2.0 ± 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.783 (KWH) | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.578 (KWH) | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.977 (KWH) | 1.3 ± 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.129 (KWH) | 0.6 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.585 (KWH) |

| Planned | 22 | 10.7 ± 10.1 | 6.5 | 2.0 ± 2.3 | 1.0 | 2.5 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.9 ± 2.2 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.9 | 0.5 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.6 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.9 ± 1.4 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Emergency and planned | 4 | 6.5 ± 4.7 | 5.5 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.5 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.7 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Not applicable | 40 | 10.5 ± 9.3 | 9.5 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.5 | 2.1 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 0.5 | 1.4 ± 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.3 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| If you needed complex dental surgery, how were the arrangements made? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I made the arrangements | 21 | 8.3 ± 9.6 | 6.0 | 0.104 (KWH) | 1.5 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.178 (KWH) | 1.9 ± 1.6 | 2.0 | 0.077 (KWH) | 1.2 ± 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.178 (KWH) | 1.1 ± 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.164 (KWH) | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.304 (KWH) | 0.7 ± 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.689 (KWH) | 0.6 ± 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.193 (KWH) |

| I was given assistance by another medical/dental practitioner. | 9 | 13.3 ± 9.2 | 12.0 | 2.2 ± 2.2 | 2.0 | 3.2 ± 1.7 | 3.0 | 2.7 ± 2.5 | 3.0 | 1.4 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.8 ± 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.5 ± 1.6 | 0.0 | 1.2 ± 1.3 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Not applicable | 39 | 10.7 ± 9.2 | 11.0 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 2.0 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.2 ± 1.3 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| OHIP-14 score | B | SE B | 95.0% CI for B | β | p-value | R2 | ΔR2 | |

| LL | UL | |||||||

| Model | 0.326 | 0.248 | ||||||

| Constant | 13.015 | 3.768 | 5.480 | 20.550 | 0.001 | |||

| Oral health daily routine (= “fairly straightforward”) | −5.855 | 3.628 | −13.110 | 1.401 | −0.354 | 0.112 | ||

| Oral health daily routine (= “a bit of a challenge”) | −3.115 | 3.373 | −9.859 | 3.629 | −0.181 | 0.359 | ||

| Oral health daily routine (= “extremely difficult”) | (reference) | |||||||

| Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) | 0.896 | 2.037 | −3.177 | 4.969 | 0.054 | 0.662 | ||

| Manual Ability Classification system (MACS) | 5.412 | 2.331 | 0.750 | 10.073 | 0.328 | 0.024 | ||

| Viking Speech Scale (VSS) | −1.908 | 2.677 | −7.261 | 3.444 | −0.099 | 0.479 | ||

| Simple dental check-up clean, no special requirements needed | −3.600 | 2.024 | −7.647 | 0.447 | −0.213 | 0.080 | ||

| Special arrangements were needed to attend the local practice | −4.051 | 2.240 | −8.531 | 0.428 | −0.201 | 0.075 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lansdown, K.; Bulkeley, K.; McGrath, M.; Irving, M.; Zagreanu, C.; Smithers-Sheedy, H. A Survey of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life for Adults with Cerebral Palsy in Australia. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13090407

Lansdown K, Bulkeley K, McGrath M, Irving M, Zagreanu C, Smithers-Sheedy H. A Survey of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life for Adults with Cerebral Palsy in Australia. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(9):407. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13090407

Chicago/Turabian StyleLansdown, Karen, Kim Bulkeley, Margaret McGrath, Michelle Irving, Claudia Zagreanu, and Hayley Smithers-Sheedy. 2025. "A Survey of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life for Adults with Cerebral Palsy in Australia" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 9: 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13090407

APA StyleLansdown, K., Bulkeley, K., McGrath, M., Irving, M., Zagreanu, C., & Smithers-Sheedy, H. (2025). A Survey of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life for Adults with Cerebral Palsy in Australia. Dentistry Journal, 13(9), 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13090407