4.1. Effectiveness of Individualized Education

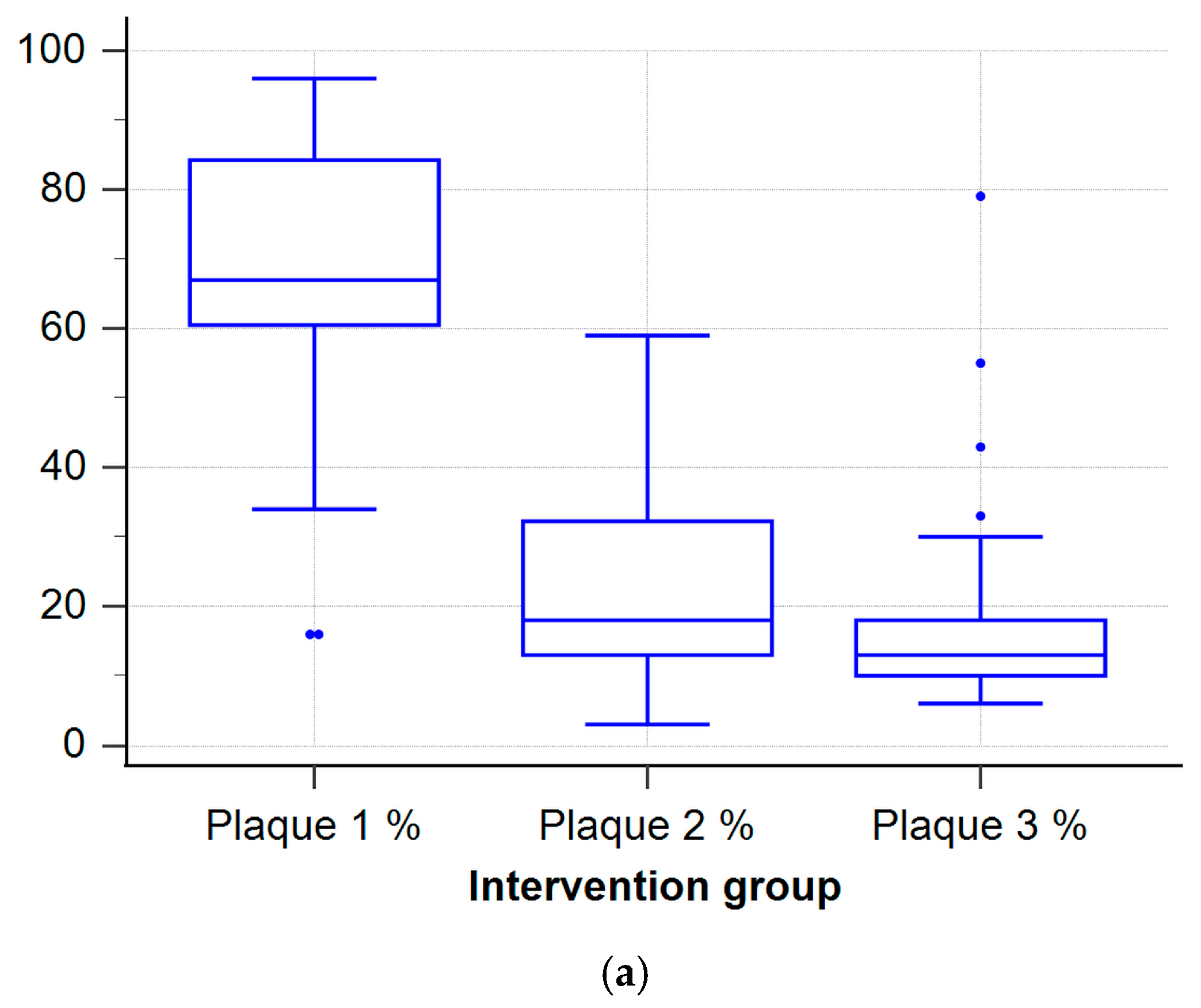

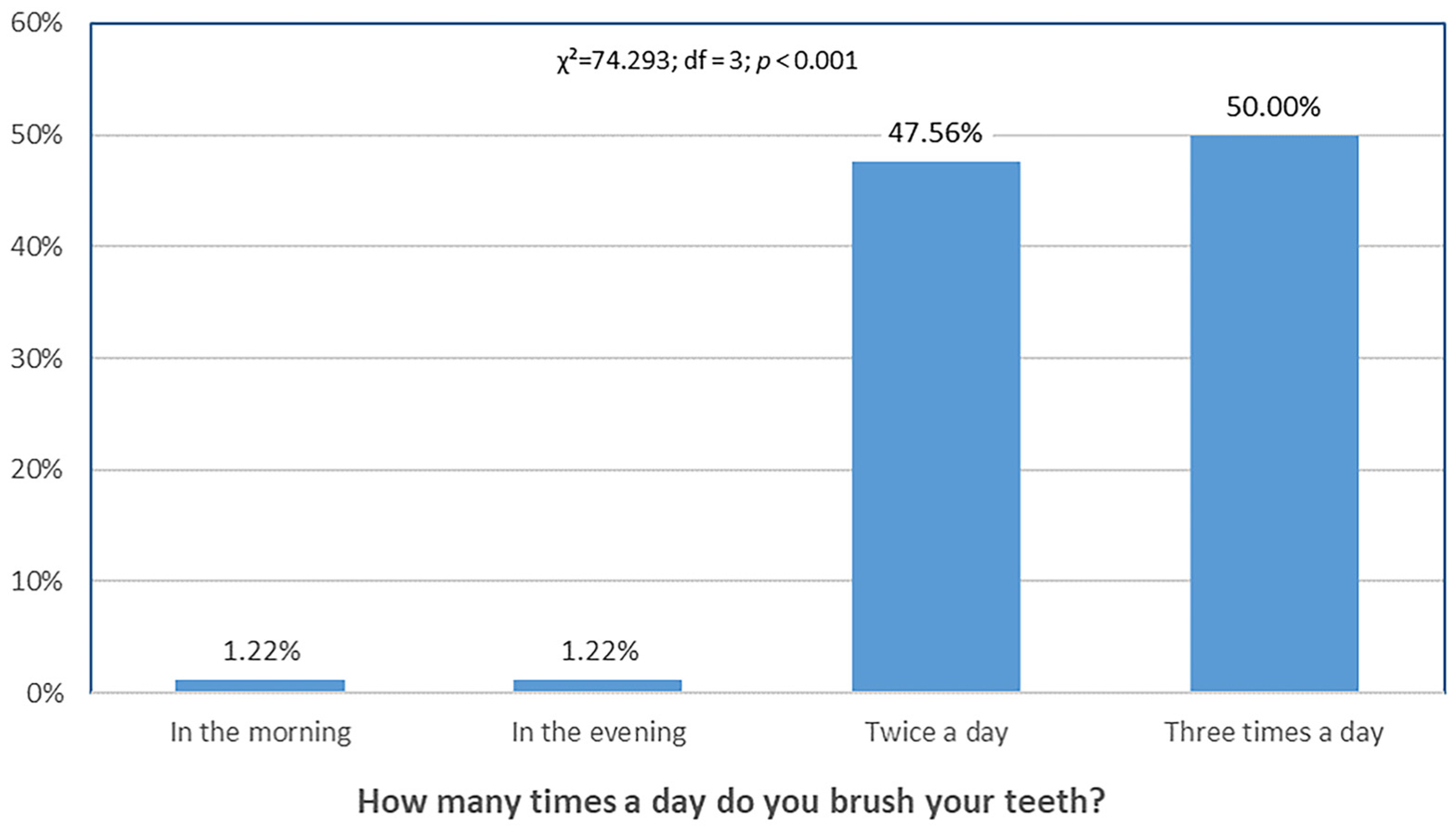

Participation in the iTOP program led to significant short-term improvements in key clinical oral health parameters, especially plaque index and bleeding on probing. While improvements were observed at 3 months, by the 2-year follow-up, most periodontal parameters, except plaque index, had returned to baseline. The short-term gains were supported by statistical significance, effect sizes, and post hoc power, whereas long-term benefits were limited. These findings suggest that a single iTOP session, without ongoing reinforcement, may be insufficient to sustain long-term periodontal benefits.

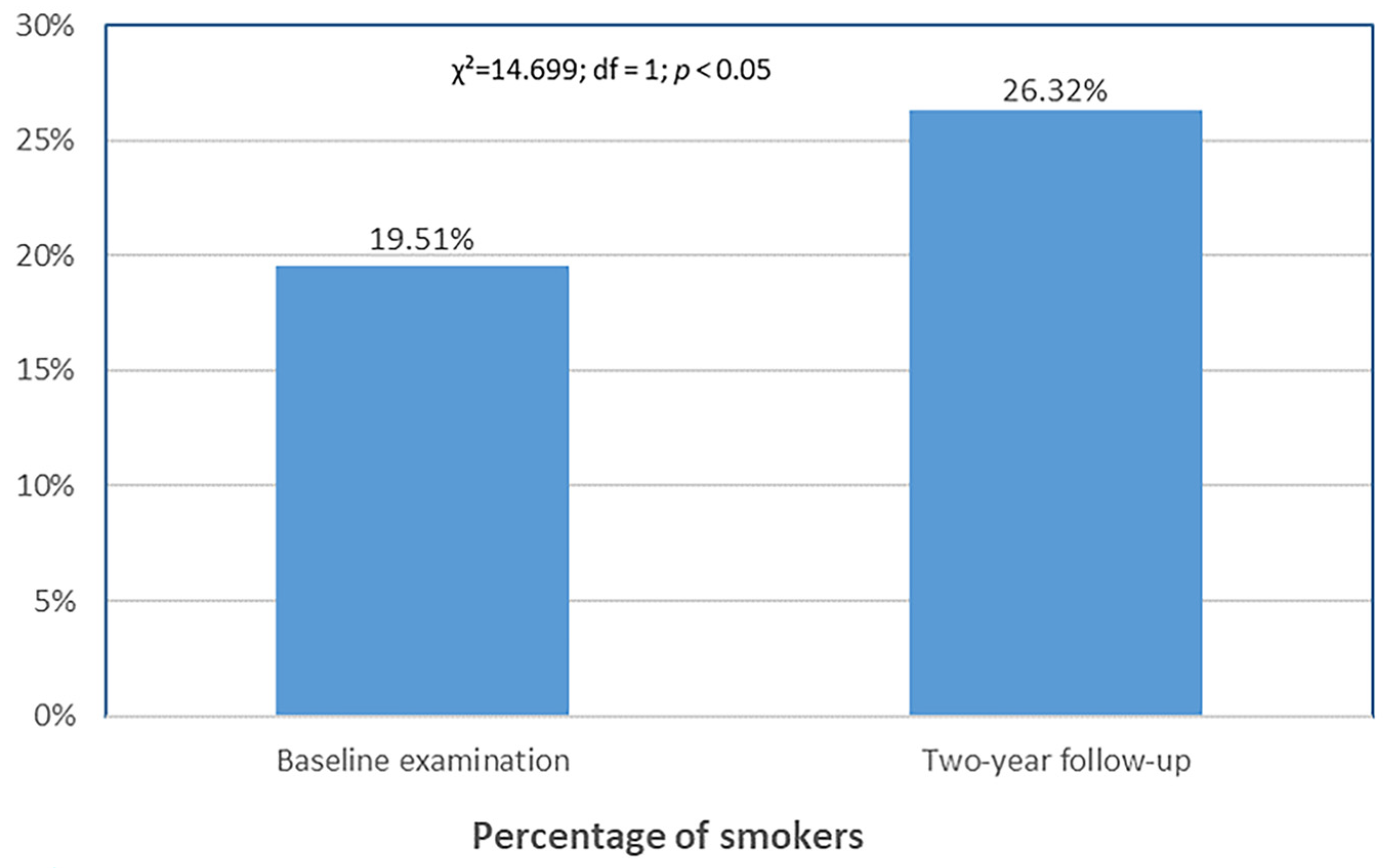

This study was intentionally designed as a single-session intervention to assess the isolated effect of an initial iTOP training, reflecting pragmatic curricular constraints where repeated sessions may be difficult to implement. The decline in effect may be due to the lack of structured reinforcement following the initial session and the high academic workload and stress faced by medical and dental students, which could deprioritize daily oral hygiene. Another explanation is the general tendency for behavioral gains to dissipate without ongoing motivation or environmental support. Since both groups showed some improvements over time, especially in plaque index, the sustained effect in the iTOP group at 2 years may reflect not only the intervention but also academic progression, enhanced oral health literacy, and curricular exposure. Consequently, long-term differences should be interpreted cautiously.

In the broader context of oral hygiene education, various protocols—ranging from classroom-based group lectures to school-based reinforcement and digital app–based motivational programs—have consistently produced short-term improvements in plaque control and gingival health. For instance, Jönsson et al. [

1] reported clinically meaningful plaque reductions after individually tailored education for periodontal patients, while school-based repeated sessions have been shown to maintain improved oral hygiene scores over short follow-ups [

19]. A recent structured group-education trial demonstrated significant short-term improvements, which diminished without reinforcement. [

2]. These results are consistent with the broader literature: iTOP’s individualized, hands-on approach produces notable initial effects, though sustained benefits likely require repeated reinforcement sessions. Long-term adherence to iTOP may be affected by individual and contextual factors such as changing intrinsic motivation, limited time, and competing academic demands. Previous studies have shown that knowledge alone does not guarantee sustained oral hygiene behavior among health profession students [

5,

6,

12], and psychosocial stressors may further reduce compliance [

13,

14]. Understanding these barriers is essential for designing interventions that achieve lasting behavior change. Future studies should assess the scalability, cost-effectiveness, and optimal frequency of booster sessions needed to maintain iTOP’s benefits within university curricula.

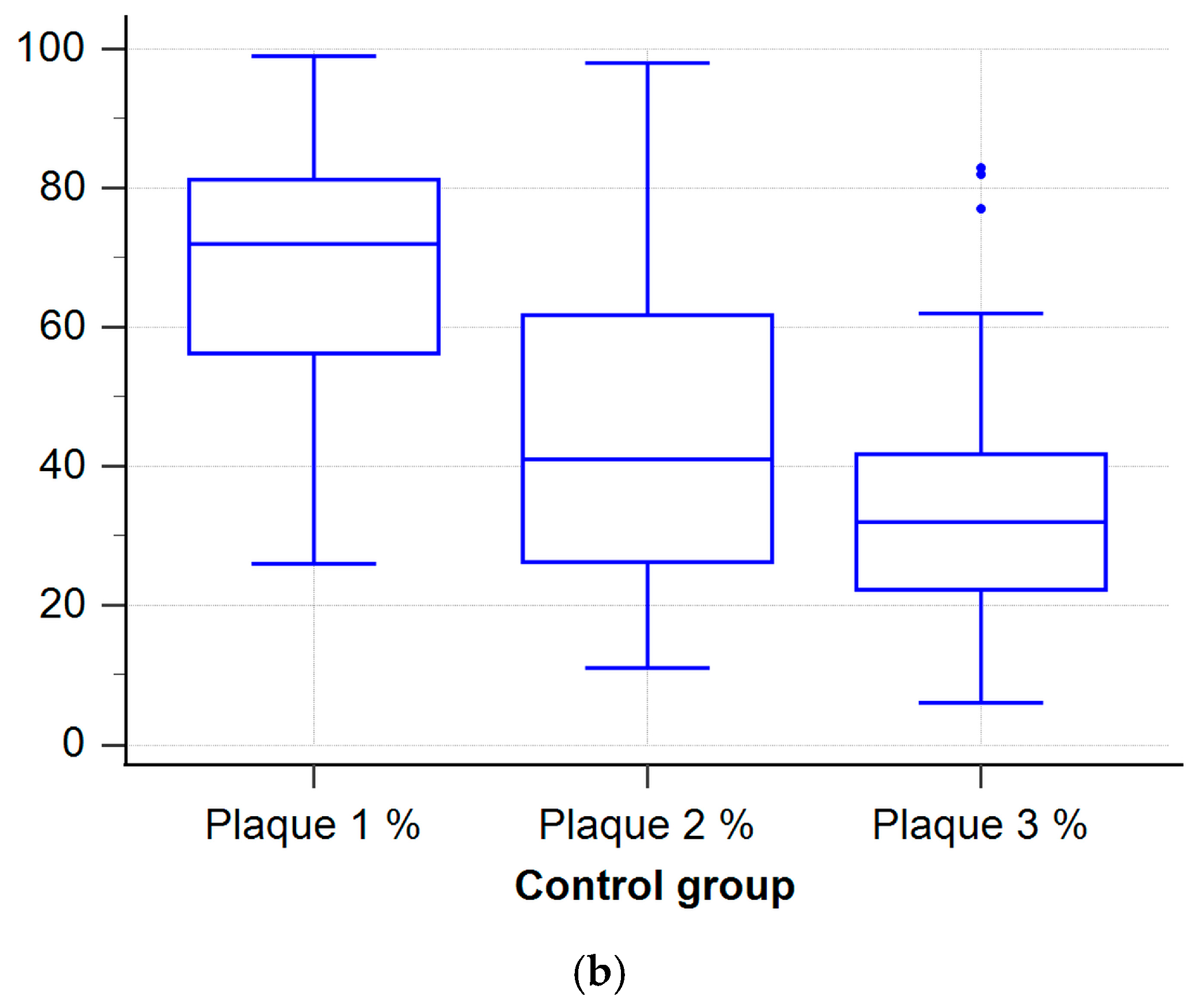

The non-iTOP group showed initial improvements, but these effects were not sustained over time. The most pronounced deterioration was observed in bleeding on probing and probing depth. These findings suggest the added value of individualized training. Although other parameters worsened, the plaque index decrease in the control group likely reflects academic progression, improved oral health literacy, and curricular exposure, rather than the intervention itself. Academic progression may partly explain this finding, since earlier studies show a link between higher education and better oral health. Higher education levels are consistently linked with increased health literacy, improved oral hygiene practices, and more favorable periodontal health [

20,

21,

22,

23].

Few cohort studies have examined how oral health changes over time after educational interventions. In a study by Kalevski et al. [

17], dental students underwent an initial oral health assessment before the educational intervention. Follow-up assessments measured clinical changes in oral health parameters. Although significant improvements were reported, oral hygiene levels among dental students remained suboptimal [

17]. A similar pattern was observed at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Mostar. Students in the iTOP group had significantly better clinical outcomes during the second and third assessments than their peers in the control group. Nevertheless, there remains room for improvement in overall oral hygiene and clinical indicators. While previous studies have examined oral health education among dental students in Southeast Europe, to our knowledge, this appears to be among the first studies to assess the long-term clinical effectiveness of a single-session iTOP intervention in both medical and dental students.

A systematic review by Nakre et al. [

18] found that short-term gains in oral health behaviors often diminish without sustained efforts, supporting the findings of this study. In the group that participated in the iTOP program, all measured parameters—except plaque index—returned to baseline values by the end of the 2-year follow-up. Although a statistically significant improvement in oral hygiene was observed at the three-month follow-up, this effect was no longer evident after two years. The findings indicate that regular education may be important for achieving lasting behavior change and better hygiene.

The findings align with health behavior theories, such as the Health Belief Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior [

24,

25], which highlight perceived benefits, self-efficacy, and ongoing external reinforcement as critical for maintaining long-term behavioral adherence. Integrating these theoretical insights can inform the development of more effective oral health education interventions aimed at maintaining improved hygiene behaviors over time.

4.3. Impact of Academic Year

Baseline data showed that older students had significantly lower plaque index than younger students. This may reflect better oral hygiene habits among more advanced students. No significant differences were observed in other periodontal parameters between the two academic levels. After two years, when the cohorts reached their third and sixth years, the groups showed no significant differences in oral health.

Most previous studies have focused on comparing oral health knowledge between medical and dental students, analyzing differences in their understanding and attitudes. Within these groups, particular attention has been given to comparing the knowledge and attitudes of junior versus senior students. Studies in the general population suggest that younger individuals often have better oral health than older adults [

29]. However, studies of medical and dental students have produced inconsistent findings regarding their knowledge and attitudes toward oral health. Yao et al. [

30] found no significant differences in oral health knowledge and attitudes between first-year medical and dental students, although the latter had marginally higher scores. In addition, third-year dental students outperformed their medical peers in the same parameters, with statistically significant differences [

30]. Other studies assessing medical students’ knowledge and attitudes have revealed a generally low level of awareness on this topic. Nevertheless, senior students showed significantly better awareness than junior ones. [

31].

Additionally, studies analyzing dental students’ attitudes toward oral health and their personal oral hygiene practices have included both preclinical and clinical students. However, findings across these studies are inconsistent. Some report no significant differences between preclinical and clinical students [

32], while others indicate that preclinical students have lower oral health knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors [

33]. This highlights the need for structured educational interventions.

Such variations may be due to differences in target populations (e.g., medical vs. dental students), as well as disparities in conceptual frameworks, methodology, questionnaire types, and sample sizes.

4.5. Study Limitations and Future Directions

The findings of this study are generally consistent with previous research, although no directly comparable study was identified. Adjusted mixed-model analyses yielded the same main conclusions as the non-parametric analyses, supporting the consistency of our findings. As with all research, several limitations should be acknowledged. Aligned with descriptive and model-based analyses, changes in probing depth and attachment level were small and not statistically significant, suggesting that the primary benefit of the intervention was in plaque control. First, this study was conducted at a single institution, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other educational settings or cultural contexts. In addition, the study population consisted exclusively of medical and dental students, who may be more motivated and knowledgeable about oral hygiene than the general public. This may have led to greater adherence to oral hygiene recommendations and, consequently, to somewhat more favorable clinical outcomes than would be expected in broader, more heterogeneous populations. Furthermore, while medical and dental students represent a relevant and high-impact group, future studies should aim to replicate these findings in other academic or community populations to enhance the external validity and generalizability of the intervention. Second, the sample size was relatively small and constrained by the number of students available per academic year. Moreover, the sample included only first/fourth- and third/sixth-year students from both medicine and dentistry programs. Furthermore, academic progression and increased curricular exposure over the 2-year follow-up may have contributed to improvements in oral health parameters in both groups, potentially confounding the observed long-term difference in plaque index. Another limitation is the Hawthorne effect, whereby participants may have improved their behavior simply because they were being observed. Repeated professional cleanings in both groups may have further amplified this effect, potentially contributing to improvements independent of the intervention. Additionally, the single-site academic setting and culturally homogeneous sample limit the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, all participants received standardized oral hygiene kits at each assessment point, which may have inadvertently influenced the control group’s behavior and diminished observable differences between the intervention and control groups. This potential bias should be considered when interpreting the results. This study assessed the effects of a single-session iTOP with only a brief 3-month reinforcement; no ongoing reinforcement beyond that was provided. Long-term adherence to the techniques was not systematically monitored, and no objective compliance measures were obtained beyond baseline self-reports, limiting attribution of 2-year outcomes solely to the intervention. Therefore, the observed decline should be viewed in light of this limitation, and outcomes could potentially differ with repeated interventions.

Although we made efforts to standardize conditions across participants, we were unable to control for all potential confounding factors. These include individual motivation, differences in curricular exposure, use of additional hygiene tools, academic stress, personal health beliefs, and other lifestyle-related behaviors. Such unmeasured variables may have influenced the outcomes and should be carefully considered in future research designs. Furthermore, the local context in which this study was conducted may have influenced the results. Factors such as the local education system, the availability of preventive dental services, and cultural attitudes toward oral hygiene may significantly influence oral health behaviors and outcomes. These contextual factors limit the generalizability of our findings to other academic or geographical settings.

Although the final response rate was high (92.7%), a small number of non-responders may still introduce attrition bias.

Future studies of this type should aim to increase the sample size and ideally include all students at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Mostar. Multiple studies have confirmed that knowledge about oral health tends to improve with age and level of education [

20,

21,

22,

23]. To ensure this trend is reflected at the University of Mostar, ongoing education and awareness campaigns on oral health should be maintained.

Given the high prevalence of oral diseases such as caries, gingivitis, and periodontitis, targeted research in specific populations, e.g., schoolchildren and university students, is essential [

40,

41]. Such studies help assess oral health awareness and support the development of preventive and educational interventions. Although results may not be immediate, investing in education is a long-term strategy for improving oral health among future generations [

42]. Educating young individuals on proper hygiene and the importance of oral health has the potential to positively influence not only their own long-term health, but also the health of those around them, particularly within their future families and professional roles.