Surgical Management of a Maxillary Odontogenic Keratocyst: A Clinical Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Anaesthesia and Incision

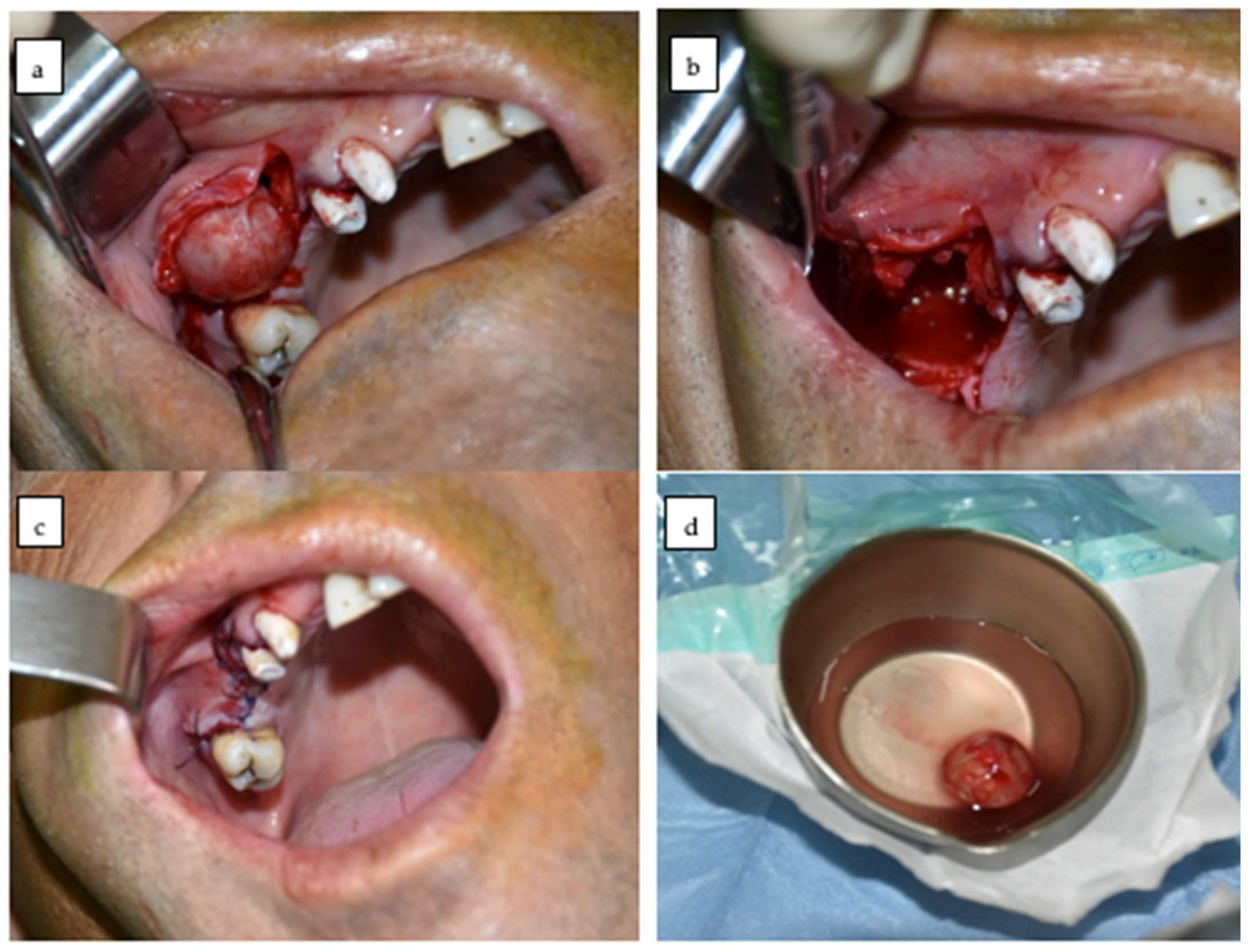

2.2. Flap Design and Elevation

2.3. Identification and Enucleation of the Lesion

2.4. Peripheral Curettage

2.5. Cystic Cavity Management

2.6. Suture and Postoperative Management

2.7. Medication Administered Following Surgery

2.8. Histopathological Processing

2.9. Follow-Up Protocol

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OKC | Odontogenic keratocyst |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| KCOT | Keratocystic odontogenic tumour |

| CBCT | Cone Beam Computed Tomography |

References

- Chen, P.; Liu, B.; Wei, B.; Yu, S. The clinicopathological features and treatments of odontogenic keratocysts. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 3479–3485. [Google Scholar]

- Ruslin, M.; van Trikt, K.; Yusuf, A.; Tajrin, A.; Fauzi, A.; Rasul, M.; Boffano, P.; Forouzanfar, T. Epidemiology, treatment, and recurrence of odontogenic and non-odontogenic cysts in South Sulawesi, Indonesia: A 6-year retrospective study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2022, 14, e247–e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egitto, S.; Forte, M.; D’Albis, G.; Testone, P.; Di Grigoli, A.; Annichiarico, A.; Limongelli, L.; Capodiferro, S. Peripheral Odontogenic Keratocyst with Periodontal Gingival Localization: Difficulties of Differential Diagnosis and Data from Literature. In Proceedings of the 1st International Online Conference on Clinical Reports, Online, 19–20 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, A.S.B.; de Sousa, A.L.A.; Falcão, C.A.M.; Ferraz, M.Â.A.L.; Gomes, J.P.P.; de Castro Lopes, S.L.P.; da Silva, P.H.B.; Costa, A.L.F.; Cardoso, L.L.C. Diffusion weighted imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient discrimination of odontogenic keratocyst. J. Oral Diagn. 2023, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soluk-Tekkesin, M.; Wright, J.M. The world health organization classification of odontogenic lesions: A summary of the changes of the 2022 (5th) edition. Turk. J. Pathol. 2022, 38, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Li, R.-F.; Man, Q.-W. Bioinformatics analysis of hub genes and oxidative stress-related pathways in odontogenic keratocysts. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 126, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favia, G.; Spirito, F.; Muzio, E.L.; Capodiferro, S.; Tempesta, A.; Limongelli, L.; Muzio, L.L.; Maiorano, E. Histopathological Comparative Analysis between Syndromic and Non-Syndromic Odontogenic Keratocysts: A Retrospective Study. Oral 2022, 2, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesi, A.; Nardi, C.; Giannitto, C.; Tironi, A.; Maroldi, R.; Di Bartolomeo, F.; Preda, L. Odontogenic keratocyst: Imaging features of a benign lesion with an aggressive behaviour. Insights Into Imaging 2018, 9, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldelaimi, A.A.K.; Enezei, H.H.; Berum, H.E.R.; Abdulkaream, S.M.; Mohammed, K.A.; Aldelaimi, T.N. Management of a dentigerous cyst; a ten-year clinicopathological study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, R.R. The Odontogenic Keratocyst (OKC) and Its Differential Diagnosis; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Titinchi, F. Protocol for management of odontogenic keratocysts considering recurrence according to treatment methods. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 46, 358–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, N.; Soman, B.P.; Das, D.; Malusare, P. OKC- Common Lesion More Misdiagnosed. Acta Sci. Dent. Sci. 2019, 3, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, M.; Speight, P. Cysts of the Oral and Maxillofacial Regions, 4th ed.; Blackwell Munksgaard: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 6–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tasca, C.; Mihailov, R. Manual de Tehnici de Laborator în Anatomie Patologică; Editura Medicală: Bucharest, Romania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Handbook for Histopathology and Cytopathology Laboratories; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272714 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Li, Y.; Li, N.; Yu, X.; Huang, K.; Zheng, T.; Cheng, X.; Zeng, S.; Liu, X. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of intact tissues via delipidation and ultrasound. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadziabdic, N.; Dzinovic, E.; Udovicic-Gagula, D.; Sulejmanagic, N.; Osmanovic, A.; Halilovic, S.; Kurtovic-Kozaric, A. Nonsyndromic Examples of Odontogenic Keratocysts: Presentation of Interesting Cases with a Literature Review. Case Rep. Dent. 2019, 2019, 9498202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, O.; Soboleski, D.; Symons, S.; Davidson, L.K.; Ashworth, M.A.; Babyn, P. Development and Duration of Radiographic Signs of Bone Healing in Children. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2000, 175, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, J.; Yapp, L.; Keating, J.; Simpson, A. Monitoring of fracture healing. Update on current and future imaging modalities to predict union. Injury 2021, 52 (Suppl. S2), S29–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, J.; Wadhwan, V.; Gotur, S.P. Orthokeratinized versus parakeratinized odontogenic keratocyst: Our institutional experience. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2022, 26, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Baughman, R.A. Maxillary odontogenic keratocyst: A common and serious clinical misdiagnosis. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2003, 134, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.M.; Vered, M. Update from the 4th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumours: Odontogenic and Maxillofacial Bone Tumors. Head Neck Pathol. 2017, 11, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioguardi, M.; Quarta, C.; Sovereto, D.; Caloro, G.A.; Ballini, A.; Aiuto, R.; Martella, A.; Muzio, L.L.; Di Cosola, M. Factors and management techniques in odontogenic keratocysts: A systematic review. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffano, P.; Cavarra, F.; Agnone, A.M.; Brucoli, M.; Ruslin, M.; Forouzanfar, T.; Ridwan-Pramana, A.; Rodríguez-Santamarta, T.; de Vicente, J.C.; Starch-Jensen, T.; et al. The epidemiology and management of odontogenic keratocysts (OKCs): A European multicenter study. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 50, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, W.A. Surgical treatment of keratocystic odontogenic tumour: A review article. Saudi Dent. J. 2011, 23, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, L.A.; Simmons, T.H.; Blitstein, B.J.; Pham, M.H.; Saha, P.T.; Phillips, C.; White, R.P.; Blakey, G.H. Modified Carnoy’s Compared to Carnoy’s Solution Is Equally Effective in Preventing Recurrence of Odontogenic Keratocysts. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 1874–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrás-Ferreres, J.; Albisu-Altolaguirre, I.; Gay-Escoda, C.; Mosqueda-Taylor, A. Long-term follow-up of a large multilocular odontogenic keratocyst. Analysis of recurrences and the applied treatments. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2024, 16, e1157–e1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sîrbu, I.; Nisipasu, I.C.; Savino, P.; Custura, A.M.; Radu, E.A.; Nastasie, V.; Sîrbu, V.D. Surgical Management of a Maxillary Odontogenic Keratocyst: A Clinical Case Report. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110514

Sîrbu I, Nisipasu IC, Savino P, Custura AM, Radu EA, Nastasie V, Sîrbu VD. Surgical Management of a Maxillary Odontogenic Keratocyst: A Clinical Case Report. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(11):514. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110514

Chicago/Turabian StyleSîrbu, Ioan, Ionut Cosmin Nisipasu, Pasquale Savino, Andreea Mihaela Custura, Elisei Adelin Radu, Vladimir Nastasie, and Valentin Daniel Sîrbu. 2025. "Surgical Management of a Maxillary Odontogenic Keratocyst: A Clinical Case Report" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 11: 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110514

APA StyleSîrbu, I., Nisipasu, I. C., Savino, P., Custura, A. M., Radu, E. A., Nastasie, V., & Sîrbu, V. D. (2025). Surgical Management of a Maxillary Odontogenic Keratocyst: A Clinical Case Report. Dentistry Journal, 13(11), 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110514