Effect of Orthodontic Tooth Movement on Sclerostin Expression in Alveolar Bone Matrix: A Systematic Review of Studies on Animal Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Focused Question and PICO

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Literature Search Protocol

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations

3. Results

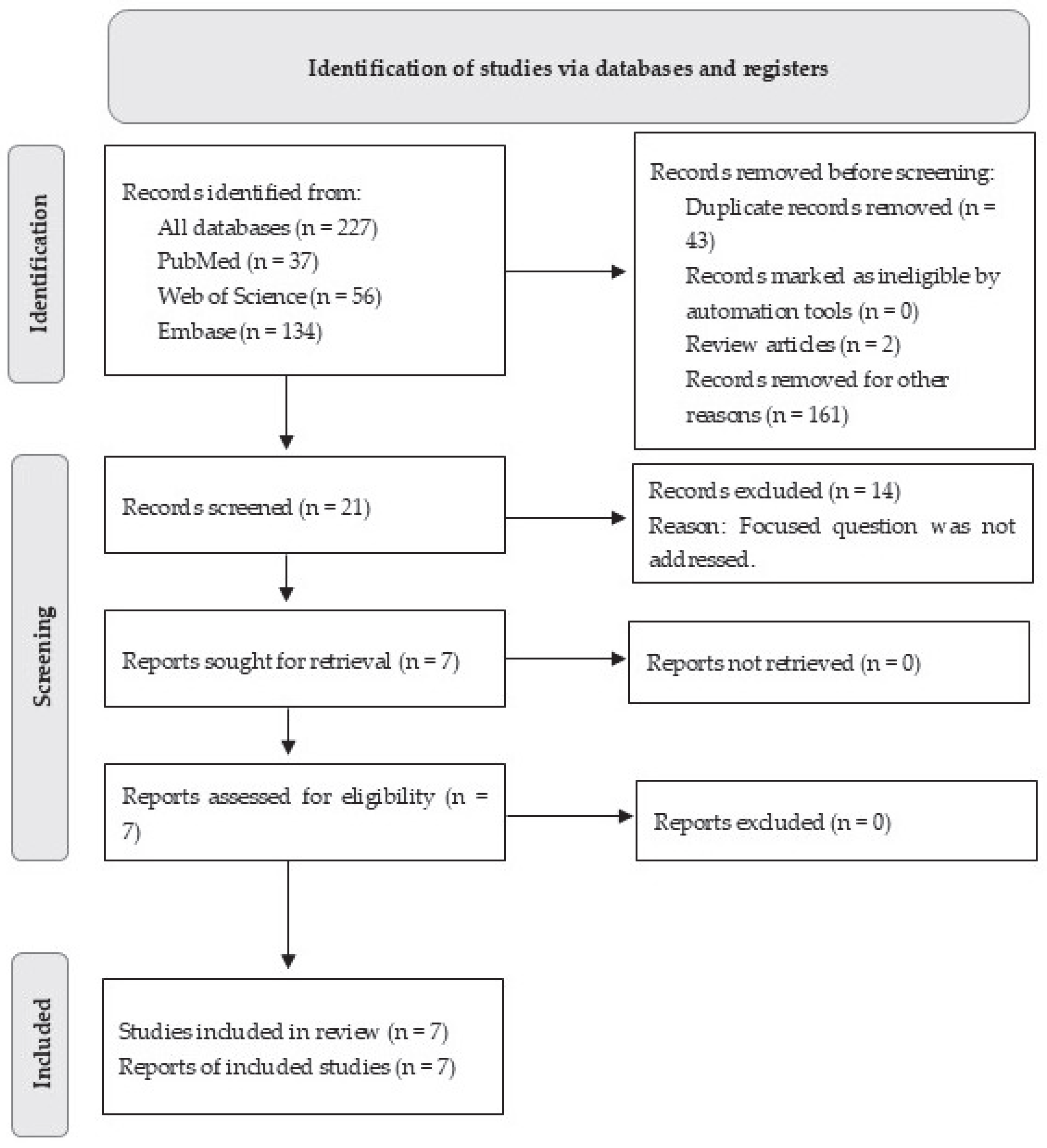

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Study Characteristics Relating to Orthodontic Tooth Movement

3.4. Sclerostin Expression

3.4.1. Sclerostin Expression on Test-Sides (Sites Exposed to OTM)

3.4.2. Sclerostin Expression on Control-Sides (Sites Unexposed to OTM)

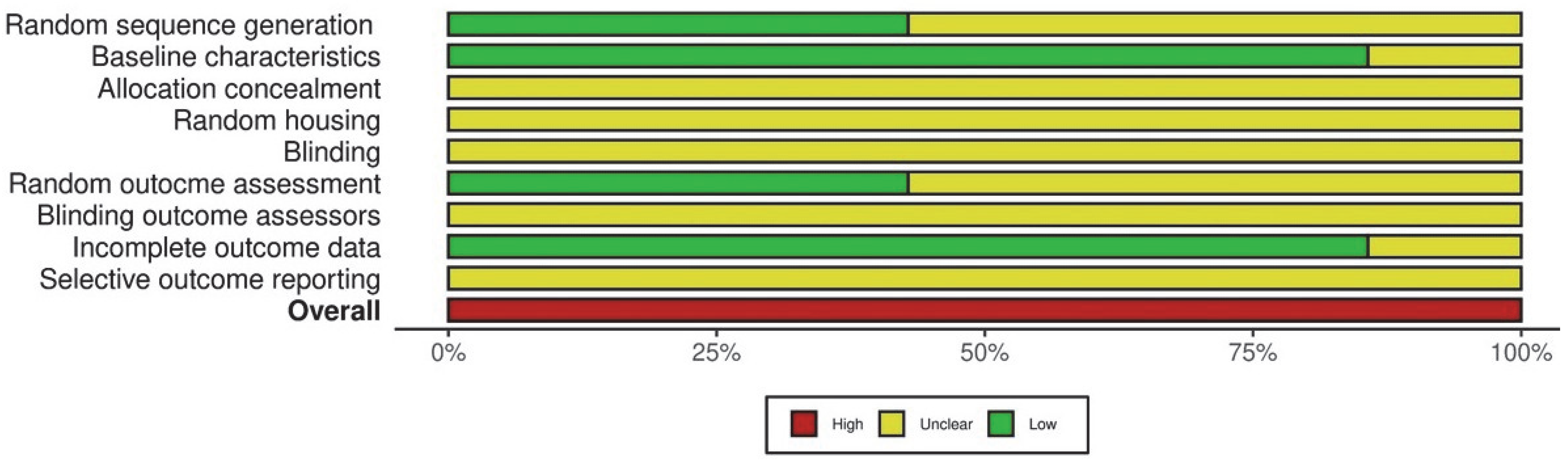

3.5. Risk of Bias and GRADE Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABM | Alveolar Bone Matrix |

| CoE | Certainty of evidence |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations |

| OTM | Orthodontic Tooth Movement |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| RANKL | Nuclear Factor-κB Ligand |

| RoB | Risk of Bias |

| SE | Sclerostin Expression |

| SOST | Sclerostin Gene |

| SYRCLE | Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory animal Experimentation |

References

- Oner, F.; Kantarci, A. Periodontal response to nonsurgical accelerated orthodontic tooth movement. Periodontology 2000 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danz, J.C.; Degen, M. Selective modulation of the bone remodeling regulatory system through orthodontic tooth movement—A review. Front. Oral Health 2025, 6, 1472711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- de Arruda, J.A.A.; Colares, J.P.; Santos, M.S.; Drumond, V.Z.; Martins, T.; André, C.B.; Amaral, F.A.; Andrade, I., Jr.; Silva, T.A.; Macari, S. Studying Orthodontic Tooth Movement in Mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2024, 210, e66884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji-Matsunaga, A.; Ono, T.; Hayashi, M.; Takayanagi, H.; Moriyama, K.; Nakashima, T. Osteocyte regulation of orthodontic force-mediated tooth movement via RANKL expression. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Parcianello, R.G.; Amerio, E.; Giner Tarrida, L.; Nart, J.; Flores Mir, C.; Puigdollers Pérez, A. Local hormones and growth factors to enhance orthodontic tooth movement: A systematic review of animal studies. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2022, 25, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Takeshita, N.; Fukunaga, T.; Seiryu, M.; Sakamoto, M.; Oyanagi, T.; Maeda, T.; Takano-Yamamoto, T. Vibration accelerates orthodontic tooth movement by inducing osteoclastogenesis via transforming growth factor-β signalling in osteocytes. Eur. J. Orthod. 2022, 44, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratton, M.P.; Londono, I.; Rompré, P.; Villemure, I.; Moldovan, F.; Nishio, C. Effect of vitamin D on bone morphometry and stability of orthodontic tooth movement in rats. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 162, e319–e327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaluparambil, M.; Abu Arqub, S.; Kuo, C.L.; Godoy, L.D.C.; Upadhyay, M.; Yadav, S. Age-stratified assessment of orthodontic tooth movement outcomes with clear aligners. Prog. Orthod. 2024, 25, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Schubert, A.; Jäger, F.; Maltha, J.C.; Bartzela, T.N. Age effect on orthodontic tooth movement rate and the composition of gingival crevicular fluid: A literature review. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2020, 81, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazan-Molina, H.; Gabet, Y.; Aizenbud, I.; Aizenbud, N.; Aizenbud, D. Orthodontic force and extracorporeal shock wave therapy: Assessment of orthodontic tooth movement and bone morphometry in a rat model. Arch. Oral Biol. 2022, 134, 105327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogawa, M.; Wijenayaka, A.R.; Ormsby, R.T.; Thomas, G.P.; Anderson, P.H.; Bonewald, L.F.; Findlay, D.M.; Atkins, G.J. Sclerostin regulates release of bone mineral by osteocytes by induction of carbonic anhydrase 2. J. Bone Min. Res. 2013, 28, 2436–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.S.; Yang, D.W.; Moon, J.S.; Kang, J.H.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, O.S.; Kim, M.S.; Koh, J.T.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, S.H. Sclerostin in periodontal ligament: Homeostatic regulator in biophysical force-induced tooth movement. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 932–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddiqi, H.; Klein-Nulend, J.; Jin, J. Osteocyte Mechanotransduction in Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2023, 21, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Lu, W.; Zhang, X.; Firth, F.; Mei, L.; Yi, J.; Gong, C.; Li, H.; Zheng, W.; Li, Y. Sclerostin injection enhances orthodontic tooth movement in rats. Arch. Oral Biol. 2019, 99, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gao, S.; Xu, T.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Lu, J.; Hu, M.; Liu, Z. Sclerostin expression in periodontal ligaments during movement of orthodontic teeth in rats. West China J. Stomatol. 2016, 34, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central]

- Shu, R.; Bai, D.; Sheu, T.; He, Y.; Yang, X.; Xue, C.; He, Y.; Zhao, M.; Han, X. Sclerostin Promotes Bone Remodeling in the Process of Tooth Movement. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0167312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Lee, J.W.; Saitou, T.; Imamura, T.; Moriyama, K.; Yamaguchi, A.; Iimura, T. Changes in the spatial distribution of sclerostin in the osteocytic lacuno-canalicular system in alveolar bone due to orthodontic forces, as detected on multimodal confocal fluorescence imaging analyses. Arch. Oral Biol. 2015, 60, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koide, M.; Kobayashi, Y. Regulatory mechanisms of sclerostin expression during bone remodeling. J. Bone Min. Metab. 2019, 37, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.; Park, W.; Choi, S.H.; Hong, N.; Huh, J.; Jung, S. Effect of anti-sclerostin antibody on orthodontic tooth movement in ovariectomized rats. Prog. Orthod. 2024, 25, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ueda, M.; Kuroishi, K.N.; Gunjigake, K.K.; Ikeda, E.; Kawamoto, T. Expression of SOST/sclerostin in compressed periodontal ligament cells. J. Dent. Sci. 2016, 11, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bullock, W.A.; Pavalko, F.M.; Robling, A.G. Osteocytes and mechanical loading: The Wnt connection. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2019, 22 (Suppl. S1), 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Yan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, W.; Liu, K.; Xue, L.; Zhou, K. Reactive oxygen species-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to osteocyte death induced by orthodontic compressive force. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2023, 86, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odagaki, N.; Ishihara, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ei Hsu Hlaing, E.; Nakamura, M.; Hoshijima, M.; Hayano, S.; Kawanabe, N.; Kamioka, H. Role of Osteocyte-PDL Crosstalk in Tooth Movement via SOST/Sclerostin. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akobeng, A.K. Understanding type I and type II errors, statistical power and sample size. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2021, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Jyothish, S.; Athanasiou, A.E.; Makrygiannakis, M.A.; Kaklamanos, E.G. Effect of nicotine exposure on the rate of orthodontic tooth movement: A meta-analysis based on animal studies. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, S.H.; Cha, J.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, B.I.; Cha, J.K.; Hwang, C.J. Effect of nicotine on orthodontic tooth movement and bone remodeling in rats. Korean J. Orthod. 2021, 51, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Peruga, M.; Lis, J. Correlation of sex hormone levels with orthodontic tooth movement in the maxilla: A prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Orthod. 2024, 46, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duursma, S.A.; Raymakers, J.A.; Boereboom, F.T.; Scheven, B.A. Estrogen and bone metabolism. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 1992, 47, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhang, B. The association between sex hormones and bone mineral density in US females. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.G.; Zaher, A.R.; Palomo, J.M.; Palomo, L. Sclerostin Modulation Holds Promise for Dental Indications. Healthcare 2018, 6, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Authors et al. | Species | Sample Size (n) | Sex | Age | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nam et al. [12] | Rats | NR | Male | 7 weeks | 200 g |

| Yiwen et al. [15] | Rats | 24 | Male | 8 weeks | 180–220 g |

| Shu et al. [16] | Rats | 35 | Male | 6–8 weeks | 180–220 g |

| Nishiyama et al. [17] | Mice | 4 | Male | 8 weeks | NR |

| Ueda et al. [20] | Rats | NR | NR | NR | 200–250 g |

| Yan et al. [22] | Rats | 16 | Male | 10–12 weeks | NR |

| Odagaki et al. [23] | Mice | NR | Male | 8 weeks | NR |

| Authors et al. | In-Group Tooth Movement (TM) | Orthodontic Force | Force Application Method | Euthanasia | Sclerostin Expression Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nam et al. [12] | Group 1: day one of OTM | 40 g | Mesialization of maxillary first molar | NR | Immunofluorescence |

| Group 2: day two of OTM | |||||

| Group 3: day 6 of OTM | |||||

| Control: sham-operated | |||||

| Yiwen et al. [15] | Group 1: OTM | 50 g | Mesialization of maxillary first molar | 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 14 days | Immunohistochemistry |

| Group 2: Untreated | |||||

| Shu et al. [16] | Group 1: 1 day of OTM | 20 g | Mesialization of maxillary first molar | 1, 3, 5, 7,

14, 21 days | Immunohistochemistry |

| Group 2: 3 days of OTM | |||||

| Group 3: 5 days of OTM | |||||

| Group 4: 7 days of OTM | |||||

| Group 5: 14 days of OTM | |||||

| Group 6: 21 days of OTM | |||||

| Nishiyama et al. [17] | Group 1: OTM | 10 g | Mesialization of maxillary first molar | 4 days | Immunofluorescence |

| Group 2: Untreated | |||||

| Ueda et al. [20] | Group 1: OTM | NR | Distalization of maxillary first molar | NR | Immunohistochemistry |

| Group 2: Untreated | |||||

| Yan et al. [22] | Group 1: OTM | 50 g | Mesialization of maxillary first molar | 3 days | ELISA |

| Group 2: Untreated | |||||

| Odagaki et al. [23] | Group 1: 0 days of OTM | 10 g | Mesialization of maxillary first molar | 0, 1, 5, 10 days | Immunofluorescence |

| Group 2: 1 day of OTM | |||||

| Group 3: 5 days of OTM | |||||

| Group 4: 10 days of OTM |

| Authors et al. | Sclerostin Expression (Tension versus Compression Sites) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Compression | Tension | |

| Nam et al. [12] | Minimal expression ^ | Increased ^ | Increased ^ |

| Yiwen et al. [15] | No sclerostin expression | Increased (day 5) ^ | Increased (day 5) ^ |

| Shu et al. [16] | No difference between mesial and distal sites ^ | Increased ^ | Decreased (day 1) ^ |

| Nishiyama et al. [17] | Increased on the distal site compared to the mesial site ^ | Similar to the control side ^ | Decreased compared to the control side ^ |

| Ueda et al. [20] | NR | Decreased † | Decreased † |

| Yan et al. [22] | 14.18 pg/mL | 22.85 pg/mL ‡ | |

| Odagaki et al. [23] | NR | Increased (day 5) ^ | Decreased (day 1) ^ |

| Author et al. | Population | Study Design | Outcome Measures | Certainty of Evidence | Strength of Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nam et al. [12] | Rats | Experimental | Immunofluorescence; In situ hybridization of SOST mRNA | Low | Weak |

| Yiwen et al. [15] | Rats | Experimental | IHC | Low | Weak |

| Shu et al. [16] | Rats | Experimental | IHC | Low | Weak |

| Nishiyama et al. [17] | Rats | Experimental | Immunofluorescence; Macroconfocal imaging | Low | Weak |

| Ueda et al. [20] | Rats | Experimental | IHC | Low | Weak |

| Yan et al. [22] | Rats | Experimental | ELISA | Low | Weak |

| Odagaki et al. [23] | Mice | Experimental | Immunofluorescence | Low | Weak |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rogers, M.L.; Rossouw, P.E.; Javed, F. Effect of Orthodontic Tooth Movement on Sclerostin Expression in Alveolar Bone Matrix: A Systematic Review of Studies on Animal Models. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110513

Rogers ML, Rossouw PE, Javed F. Effect of Orthodontic Tooth Movement on Sclerostin Expression in Alveolar Bone Matrix: A Systematic Review of Studies on Animal Models. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(11):513. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110513

Chicago/Turabian StyleRogers, Meredith L., Paul Emile Rossouw, and Fawad Javed. 2025. "Effect of Orthodontic Tooth Movement on Sclerostin Expression in Alveolar Bone Matrix: A Systematic Review of Studies on Animal Models" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 11: 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110513

APA StyleRogers, M. L., Rossouw, P. E., & Javed, F. (2025). Effect of Orthodontic Tooth Movement on Sclerostin Expression in Alveolar Bone Matrix: A Systematic Review of Studies on Animal Models. Dentistry Journal, 13(11), 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110513