Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) as a Tool for the Assessment of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

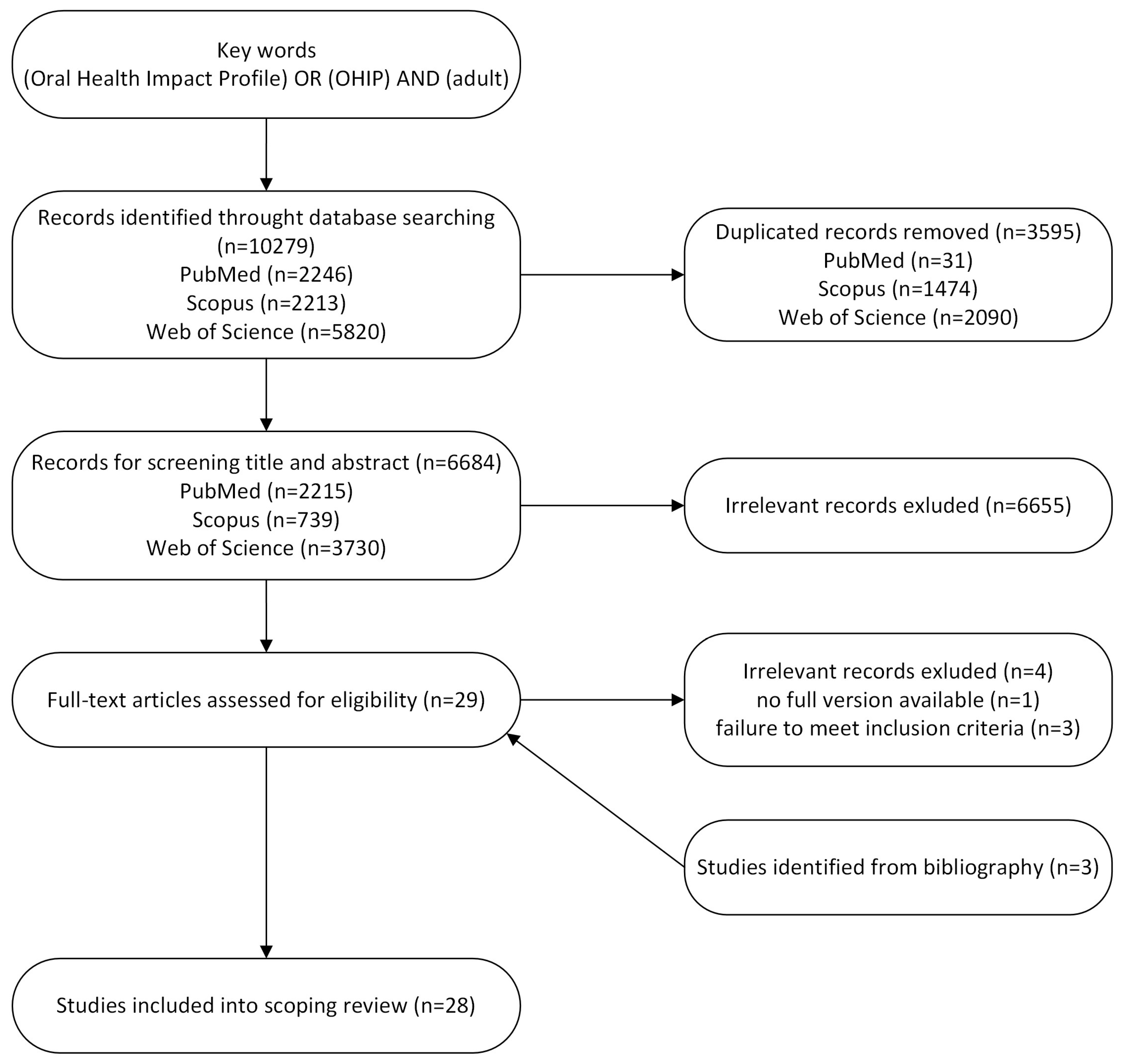

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Framework

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection and Extraction of Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Generic OHIPs

3.2. Condition-Specific OHIPs

4. Discussion

Future Research Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| OHRQoL | Oral health-related quality of life |

| dPRO | Dental patient-related outcomes |

| VAS | Visual analog scale |

| OHIP | Oral Health Impact Profile |

| GOHAI | Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index |

| ODIP | Oral Impact on Daily Performance |

| EORTC QLQ OH-17 | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire. Oral Supplement |

| ADD | Additive method |

| SC | Simple count method |

| MID | Minimal important difference |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| PRISMA Scr | The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews |

| PCC | Population, concept, context |

| sign lang | Sign language |

References

- World Health Organization. Basic Documents: Forty-Ninth Edition. Geneva. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/pdf_files/Bd_49th-en.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Locker, D. Measuring oral health: A conceptual framework. Community Dent. Health 1988, 5, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P.F. Assessment of oral health related quality of life. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.T.; Omara, M.; Su, N.; List, T.; Sekulic, S.; Häggman-Henrikson, B.; Visscher, C.M.; Bekes, K.; Reissmann, D.R.; Baba, K.; et al. Recommendations for use and scoring of oral health impact profile versions. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2022, 22, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissmann, D.R. Methodological considerations when measuring oral health-related quality of life. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021, 48, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, G.D. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1997, 25, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sischo, L.; Broder, H.L. Oral health-related quality of life: What, why, how, and future implications. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, H.; John, M.T.; Sekulić, S.; Theis-Mahon, N.; Rener-Sitar, K. Patient-reported outcome measures for adult dental patients: A systematic review. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2019, 19, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennadi, D.; Reddy, C.V.K. Oral health related quality of life. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2013, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginson, I.J.; Carr, A.J. Measuring quality of life: Using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ. 2001, 322, 1297–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.H.H.; Cheung, C.S.; McGrath, C. Developing a short form of oral health impact profile (OHIP) for dental aesthetics: OHIP-aesthetic. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Seoane, M.; Reichenheim, M.E.; Tsakos, G.; Celeste, R.K. Adult oral health-related quality of life instruments: A systematic review. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2022, 50, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, I.B.; Cleary, P.D. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995, 273, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.T.; Hujoel, P.; Miglioretti, D.L.; LeResche, L.; Koepsell, T.D.; Micheelis, W. Dimensions of oral-health-related quality of life. J. Dent. Res. 2004, 83, 956–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, R.; Durham, J.; Wassell, R.W.; Preshaw, P.M. Does the mode of administration of the oral health impact profile-49 affect the outcome score? J. Dent. 2014, 42, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zaror, C.; Pardo, Y.; Espinoza-Espinoza, G.; Pont, À.; Muñoz-Millán, P.; Martínez-Zapata, M.J.; Vilagut, G.; Forero, C.G.; Garin, O.; Alonso, J.; et al. Assessing oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: A systematic review and standardized comparison of available instruments. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, J.; Steele, J.G.; Wassell, R.W.; Exley, C.; Meechan, J.G.; Allen, P.F.; Moufti, M.A. Creating a patient-based condition-specific outcome measure for temporomandibular disorders (TMDs): Oral health impact profile for TMDs (OHIP-TMDs). J. Oral Rehabil. 2011, 38, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, G.D.; Spencer, A.J. Development and evaluation of the oral health impact profile. Community Dent. Health 1994, 11, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Locker, D.; Allen, P.F. Developing short-form measures of oral health-related quality of life. J. Public Health Dent. 2002, 62, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps. Geneva. 1980. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/41003/9241541261_eng.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Almeida, I.F.B.; Freitas, K.S.; Almeida, D.B.; Silva, I.C.O.; Oliveira, M.C. Locker’s conceptual model of oral health: A reflective study. REVISA 2023, 12, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.T.; Feuerstahler, L.; Waller, N.; Baba, K.; Larsson, P.; Celebić, A.; Kende, D.; Rener-Sitar, K.; Reissmann, D.R. Confirmatory factor analysis of the oral health impact profile. J. Oral Rehabil. 2014, 41, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.T.; Reissmann, D.R.; Feuerstahler, L.; Waller, N.; Baba, K.; Larsson, P.; Celebić, A.; Szabo, G.; Rener-Sitar, K. Exploratory factor analysis of the oral health impact profile. J. Oral Rehabil. 2014, 41, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacEntee, M.I.; Brondani, M. Cross-cultural equivalence in translations of the oral health impact profile. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2016, 44, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, J.M.; Hoogstraten, J. Item-order effects in the oral health impact profile (OHIP). Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2008, 116, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buunk-Werkhoven, Y.A.B.; Barelds, D.P.H.; Dijkstra, A.; Buunk, A.P. A two-dimensional scale for oral discomfort. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Gibson, B.; Locker, D. Is the oral health impact profile measuring up? Investigating the scale’s construct validity using structural equation modelling. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2008, 36, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.T.; Patrick, D.L.; Slade, G.D. The German version of the oral health impact profile—Translation and psychometric properties. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2002, 110, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustaoğlu, G.; Göller Bulut, D.; Gümüş, K.Ç.; Ankarali, H. Evaluation of the effects of different forms of periodontal diseases on quality of life with OHIP-14 and SF-36 questionnaires: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2019, 17, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägglin, C.; Berggren, U.; Hakeberg, M.; Edvardsson, A.; Eriksson, M. Evaluation of a Swedish version of the OHIP-14 among patients in general and specialist dental care. Swed. Dent. J. 2007, 31, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Mounssif, I.; Bentivogli, V.; Rendón, A.; Gissi, D.B.; Maiani, F.; Mazzotti, C.; Mele, M.; Sangiorgi, M.; Zucchelli, G.; Stefanini, M. Patient-reported outcome measures after periodontal surgery. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2023, 27, 7715–7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coca, K.K.; Reed, L.; Horton, S.; Gillespie, M.B. Outcomes of the salivary-oral health impact profile (S-OHIP) for chronic salivary disorders. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2023, 44, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, A.; Erdelt, K.; Rasche, E.; Schmitter, M.; Edelhoff, D.; Liebermann, A. Impact of Missing Teeth on Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life: A Prospective Bicenter Clinical Trial. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 35, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuk, J.G.; Lindeboom, J.A.; Tan, M.L.; de Lange, J. Impact of orthognathic surgery on quality of life in patients with different dentofacial deformities: Longitudinal study of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14) with at least 1 year of follow-up. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 26, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfadda, S.A.; Al-Fallaj, H.A.; Al-Banyan, H.A.; Al-Kadhi, R.M. A clinical investigation of the relationship between the quality of conventional complete dentures and the patients’ quality of life. Saudi Dent. J. 2015, 27, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.A.; Lund, J.P.; Shapiro, S.H.; Locker, D.; Klemetti, E.; Chehade, A.; Savard, A.; Feine, J.S. Oral health status and treatment satisfaction with mandibular implant overdentures and conventional dentures: A randomized clinical trial in a senior population. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2003, 16, 390–396. [Google Scholar]

- Torrpa-Saarinen, E. Interplay Between Treatment Need, Service Use and Perceived Oral Health. A Longitudinal, Population-Based Study; University of Eastern Finland: Kuopio, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Verrips, G.H.W.; Schuller, A.A. Subjective Oral Health in Dutch Adults. Dent. J. 2013, 1, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.T. Standardization of dental patient-reported outcomes measurement using ohip-5—Validation of “recommendations for use and scoring of oral health impact profile versions”. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2022, 22, 101645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingleshwar, A.; John, M.T. Cross-cultural adaptations of the oral health impact profile—An assessment of global availability of 4-dimensional oral health impact characterization. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2023, 23, 101787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.T.; Miglioretti, D.L.; LeResche, L.; Koepsell, T.D.; Hujoel, P.; Micheelis, W. German short forms of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2006, 34, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, M.; Al-Shamrany, M.; Locker, D.; Allen, F.; Feine, J. Effect of reducing the number of items of the Oral Health Impact Profile on responsiveness, validity and reliability in edentulous populations. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2008, 36, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, A.E.; Slade, G.D.; Lim, S.; Reisine, S.T. Impact of oral disease on quality of life in the US and Australian populations. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2009, 37, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León, S.; Correa-Beltrán, G.; De Marchi, R.J.; Giacaman, R.A. Ultra-short version of the oral health impact profile in elderly Chileans. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, H.; Locker, D.; Mock, D.; Tenenbaum, H.C. Pain and the quality of life in patients referred to a craniofacial pain unit. J. Orofac. Pain 1996, 10, 316–323. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, F.; Locker, D. A modified short version of the oral health impact profile for assessing health-related quality of life in edentulous adults. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2002, 15, 446–450. [Google Scholar]

- Dueled, E.; Gotfredsen, K.; Trab Damsgaard, M.; Hede, B. Professional and patient-based evaluation of oral rehabilitation in patients with tooth agenesis. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2009, 20, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, J.; Macedo, C.; López-Valverde, A.; Bravo, M. Validation of the oral health impact profile (OHIP-20sp) for Spanish edentulous patients. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2012, 17, e469–e476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusson, V.; Caron, C.; Gaudreau, P.; Morais, J.A.; Shatenstein, B.; Payette, H. Assessing Older Adults’ Masticatory Efficiency. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 1192–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, N.J.; Moral, J. Adaptation and content validity by expert judgment of the Oral Health Impact Profile applied to Periodontal Disease. J. Oral Res. 2017, 6, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, J.; Wei, S.; Ji, P. Development and validation of a condition-specific measure for chronic periodontitis: Oral health impact profile for chronic periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, P.; Pereira, P.A.; Nunes, M.; Mendes, R.A. Validation of a Portuguese version of the Oral Health Impact Profile adapted to people with mild intellectual disabilities (OHIP-14-MID-PT). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wąsacz, K.; Pac, A.; Darczuk, D.; Chomyszyn-Gajewska, M. Validation of a modified Oral Health Impact Profile scale (OHIP-14) in patients with oral mucosa lesions or periodontal disease. Dent. Med. Probl. 2019, 56, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulekha, S.G.; Thomas, S.; Narayan, V.; Gomez, M.S.S.; Gopal, R. Translation and validation of oral health impact profile-14 questionnaire into Indian sign language for hearing-impaired individuals. Spec. Care Dentist. 2020, 40, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Chaparro, J.P.; Plaza-Ruíz, S.P.; Camacho-Usaquén, T.; Pasuy-Caicedo, J.A.; Villamizar-Rivera, A.K. Modified short version of the oral health impact profile for patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Braz. J. Oral Sci. 2021, 20, e211717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Huang, S.S.; Moore Simas, T.A.; Silk, H.; Savageau, J.A.; Russell, S.L. The MOHIP-14PW (Modified Oral Health Impact Profile 14-Item Version for Pregnant Women): A Real-World Study of Its Psychometric Properties and Relationship with Patient-Reported Oral Health. Healthcare 2022, 10, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.B.; Yap, A.U.; Sim, Y.F.; Allen, P.F. The oral and systemic health impact profile for periodontal disease (OSHIP-Perio)-Part 1: Development and validation. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2024, 22, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.B.; Yap, A.U.; Sim, Y.F.; Allen, P.F. The oral and systemic health impact profile for periodontal disease (OSHIP-Perio)-Part 2: Responsiveness and minimal important difference. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2024, 22, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meulen, M.J.; John, M.T.; Naeije, M.; Lobbezoo, F. Developing abbreviated OHIP versions for use with TMD patients. J. Oral Rehabil. 2012, 39, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, L.A.; Peltomäki, T.; Marôco, J.; Campos, J.A.D.B. Use of Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14) in Different Contexts. What Is Being Measured? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 13412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierwald, I.; John, M.T.; Durham, J.; Mirzakhanian, C.; Reissmann, D.R. Validation of the response format of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 119, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanaik, S.; Lee, C.H.; John, M.T.; Chanthavisouk, P.; Paulson, D. Is assessment of oral health-related quality of life burdensome? An item nonresponse analysis of the oral health impact profile. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possebon, A.P.D.R.; Faot, F.; Machado, R.M.M.; Nascimento, G.G.; Leite, F.R.M. Exploratory and confirmatory factorial analysis of the OHIP-Edent instrument. Braz. Oral Res. 2018, 32, e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.M.; de Oliveira, B.H.; Nadanovsky, P.; Hilgert, J.B.; Celeste, R.K.; Hugo, F.N. The Oral Health Impact Profile-14: A unidimensional scale? Cad. Saude Publica 2013, 294, 749–757. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, A.; John, M.T.; Kohli, N.; Self, K.; Flynn, P. Validation of the English-language version of 5-item Oral Health Impact Profile. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2016, 60, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, R.; Mizoue, T.; Yamamoto, R.; Tsuneoka, M. Development of a shortened Japanese version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) for young and middle-aged adults. Community Dent. Health 2008, 25, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Solanke, C.; John, M.T.; Ebel, M.; Altner, S.; Bekes, K. OHIP-5 for school-aged children. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2024, 24, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myint Oo, K.Z.; Fueki, K.; Yoshida-Kohno, E.; Hayashi, Y.; Inamochi, Y.; Wakabayashi, N. Minimal clinically important differences of oral health-related quality of life after removable partial denture treatments. J. Dent. 2020, 92, 103246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database (Date) | Search Strategy | No. of Records | No. of Records After Deduplication |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed (25 May 2025) | (Oral Health Impact Profile [All fields]) OR (OHIP [All fields]) AND (Adult [All fields) AND (adult [filters]) AND (English [filters])) | 2246 | 2215 |

| Web of Science (28 May 2025) | ((Oral Health Impact Profile [All Fields]) OR (OHIP [All Fields]) AND (Adult [All Fields]) AND (English [filters]) | 2213 | 739 |

| Scopus (28 May 2025) | ALL FIELDS (“Oral Health Impact Profile”) OR ALL FIELDS (“OHIP”) AND ALL FIELDS (“Adult”) AND English (filters) AND adult (filters) | 5820 | 3730 |

| OHIP Version | Authors | Year | Population | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OHIP-49 | Slade GD, Spencer AJ. [19] | 1994 | general population | Australia |

| OHIP-14 | Slade GD. [6] | 1997 | general population | Australia |

| OHIP-14 | Locker D, Allen PF. [20] | 2002 | general population | Canada |

| OHIP-46 | John MT et al. [15] | 2004 | general population | Germany |

| OHIP-21G | John MT et al. [15,46] | 2004 | general population | Germany |

| OHIP-5G | John MT et al. [46] | 2006 | general population | Germany |

| OHIP-22 | Baker SR et al. [28] | 2008 | general population | Canada |

| OHIP-42 | Awad M et al. [47] | 2008 | general population | Canada |

| NHANES-OHIP | Sanders AE et al. [48] | 2009 | general population | USA |

| OHIP-7 | León S et al. [49] | 2017 | general population | Chile |

| OHIP Oral discomfort | Buunk-Werkhoven YAB et al. [27] | 2025 | general population | Netherlands |

| OHIP-30-TMD | Murray H et al. [50] | 1996 | patients with temporomandibular disorders | Netherlands |

| OHIP-EDENT | Allen F et al. [51] | 2002 | edentulous patients | Canada, UK |

| OHIP- aesthetic | Wong AH et al. [11] | 2007 | patients with dental aesthetic problems (e.g., teeth discoloration) | China |

| OHIP aesthetic outcomes | Dueled E et al. [52] | 2009 | evaluation of aesthetic treatment | Denmark |

| OHIP-TMDs | Durham J et al. [53] | 2011 | patients with temporomandibular disorders | UK/Ireland |

| POST-OHIP-13 | Montero J et al. [54] | 2012 | edentulous patients’ treatment outcome | Spain |

| OHIP perception of masticatory efficiency | Cusson V et al. [55] | 2015 | masticatory efficiency evaluation | Canada |

| OHIP-PD | Rodríguez NI et al. [56] | 2017 | patients with periodontal disease | Mexico |

| OHIP-CP | He S et al. [57] | 2017 | patients with chronic periodontal disease | China |

| OHIP-14-MID-PT | Couto P et al. [58] | 2018 | adults with mild intellectual disabilities | Portugal |

| mOHIP-14 | Wąsacz K et al. [59] | 2019 | patients with mucosa lesions or periodontal disease | Poland |

| OHIP-12 sign lang. | Sulekha SG et al. [60] | 2020 | hearing-impaired people | India sign language |

| OHIP-s14-Ortho | Barrera-Chaparro JP et al. [61] | 2021 | adults and children with fixed orthodontic appliances | Columbia |

| MOHIO-14PW | Yang C et al. [62] | 2022 | pregnant women | USA |

| S-OHIP | Coca KK et al. et al. [63] | 2023 | patients with chronic salivary disorders | USA |

| OSHIP-Perio | Wong LB et al. [64,65] | 2024 | patients with periodontal disease | Singapore |

| Name | Items | Recall Period | Range of Responses | Development/ Item Selection Process | Subscales (No. of Items According to OHIP-49) | Modifications | Reliability/ Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OHIP-49 [18] | 49 | 1 year | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never I don-t know | 535 statements received during interviews with patients were assessed by experts who chose 46 items, and 3 additional items were added from existing tools items relocated to seven domains based on Locker’s conceptual model | 7 domains functional limitation (1–9), physical pain (10–18), psychological discomfort (19–23), physical disability (24–32), psychological disability (33–38), social disability (39–43), handicap (44–49) | tested for convergent validity | |

| OHIP-14 [6] | 14 | 1 year | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never I don-t know | derived from OHIP-49 by eliminating 3 questions regarding denture-related problems and 7 questions where 5% or more of responses were left unanswered or answered “I don’t know” statistical approach (internal reliability, principal component factor, and least-squares regression) used to choose final set of items (two items per dimension) | 7 dimensions functional limitation (2, 6), physical pain (9, 15), psychological discomfort (20, 23), physical disability (29, 32), psychological disability (35, 38), social disability (42, 43), handicap (47, 48) | tested for discriminative validity | |

| OHIP-14 [19] | 14 | 3 months | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never I don-t know | derived from OHIP-49 by the item-impact method two top-scoring items from each subscale | 7 subscales: functional limitation (1, 7), physical pain (12, 16), psychological discomfort (19, 21), physical disability (24, 28), psychological disability (34, 36), social disability (40, 42), handicap (45, 47) | tested for reliability, content, discriminative and concurrent validity, sensitivity to change, and stability | |

| OHIP-46 [14] | 46 | 1 month | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | derived from OHIP-53G (German version of OHIP-49) by exclusion of 4 items specified for German population and 3 items Q9, Q18, and Q30 referring to dentures | 4 factors psychological impact, orofacial pain, oral functions, appearance | re-framework of the dimensional structure by the exploratory factor analysis (4 factors) indicated in younger populations | |

| OHIP-21 [14,45] | 21 | 1 month | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | based on OHIP-G and two versions of OHIP-14 items selected by the factor of analytic method used in other study (John Dimensions) | 4 dimensions psychological impact (36, 37, 38, 40, 42, 43, 48, 49), orofacial pain (10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17), oral functions (1, 2, 4), appearance (3, 19, 22) | items loaded to 4 dimensions | tested for content and construct validity, responsiveness, and reliability |

| OHIP-5 [45] | 5 | not stated | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | based on OHIP-G and two versions of OHIP-14 regression models with clinical impact | 4 dimensions psychological impact (43), orofacial pain (10), oral functions (1), appearance (22) item without dimension: 26 | items loaded to 4 dimensions | tested for content and construct validity, responsiveness, and reliability |

| OHIP-22 [27] | 22 | 3 months | 5—very often 4—fairly often 3—occasionally 2—hardly ever 1—never I don-t know | derived from OHIP-49 items selected by confirmatory factor analysis | 6 factors functional limitation (1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7), pain (9, 11, 16), psychological impact (21, 23, 34, 35, 36), physical disability (27, 28, 29, 32), social disability (40, 41), handicap (45, 48) | scale re-specified to the six-factor model | tested for within- and between-construct validity |

| OHIP-42 [46] | 42 | 1 month | 6—all of the time 5—most of the time 4—some of the time 3—occasionally 2—rarely 1—never I don-t know | derived from OHIP-14 by the expert panel and item-impact method and mean frequency rating | 7 domains functional limitation (1, 2, 4–9), physical pain (10, 12, 15, 17, 18), psychological discomfort (19, 20, 22–23), physical disability (24–26, 28–32), psychological disability (33–38), social disability (39–43), handicap (44–49) | range of possible answers wider than in OHIP-49 | tested for reliability and construct validity |

| NHANES-OHIP [47] | 7 | 1 year | 1- very often 2—fairly often 3—occasionally 4—hardly ever 5—never I don’t know | 7 items derived from OHIP-14 according to Slade | 6 dimensions functional limitation (6), physical pain (10, 16), psychological discomfort combine with psychological disability (20 combined with 38), physical disability (28), social disability (43), handicap (47) | some wording changes compared to OHIP-14 the reverse codes were used | tested for construct validity and adequacy |

| OHIP-7 [48] | 7 | 1 year | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | derived from OHIP-49 one item from each dimension was selected by linear regression | 7 dimensions functional limitation (8), physical pain (13), psychological discomfort (21), physical disability (24), psychological disability (33), social disability (43), handicap (48) | ||

| OHIP Oral discomfort [26] | 11 | not stated | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—regularly 1—sometimes 0—never | derived from OHIP-14 by confirmatory factor analysis and simultaneous components analysis | 2 factors psychological discomfort (20, 42, 38, 23, 47, 35), physical discomfort (10, 43, 16, 32, 29) | one-factor scale for assessment of oral discomfort with two subscales from dimensions of psychological discomfort and physical discomfort change in most often used options of answers coded 1 and 2 |

| Name | Items | Recall Period | Range of Responses | Development/ Item Selection Procedure | Subscales (No. of Items According to OHIP-49) | Modifications | Reliability/ Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OHIP-30-TMD [49] | 30 | 1 month | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | panel of experts reduced items from OHIP-49 (physical pain items and those not relevant to the facial pain were removed) | 7 subscales functional limitation (1, 2, new item), psychological discomfort (19–21, 23), physical disability (24, 25, 27, 28, 43, 32, 16), psychological disability (33–38), social disability (39–42, new item, 31), handicap (46–49) | the expression “teeth, mouth, or dentures” changed into “pain” new items added: “taking longer to complete meals” and “avoiding eating with others” some items relocated to the other domain | tested for internal consistency |

| OHIP-EDENT [50] | 19 | not stated | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | derived from OHIP-49 item impact method used in two populations top two ranked items from each domain from each population (Australian and British) were included | 7 domains functional limitation (1, 7, 9), physical pain (10, 16, 17, 18), psychological discomfort (19, 20), physical disability (28, 32, 30), psychological disability (34, 38), social disability (40, 42, 39), handicap (46, 47) | tested for sensitivity to change and stability | |

| OHIP- aesthetic [11] | 14 | 2 weeks | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | derived from OHIP-49 two approaches were tested: the conceptual method based on the experts choice of the most suitable items vs. the regression methods the expert-based approach showed better sensitivity for assessing dental aesthetics outcomes | 7 domains functional limitation (3, 4), physical pain (13, 17), psychological discomfort (20, 22), physical disability (26, 31), psychological disability (35, Q8), social disability (40, 43), handicap (46, 47) | tested for internal reliability, discriminating ability, responsiveness, and sensitivity to change | |

| OHIP aesthetic outcome [51] | 6 | after treatment | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | derived from OHIP-49 items selected by authors | no subscales Items: 3, 4, 20, 22, 31, 38 | ||

| OHIP-TMDs [17] | 22 | 1 month | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | mixed methods including statistical analysis of OHIP-49 (quantitative study) and interviews (qualitative study) supported by the authors’ experience | 7 domains functional limitation (1, new item), physical pain (10, 11, 12, 16, new item), psychological discomfort (19, 20, 21, 23), physical disability (28, 32), psychological disability (33, 34, 35, 36, 37), social disability (42, 43), handicap (47, 49) | OHIP 49 items were modified by adding “jaws” to the expression “teeth, mouth, or dentures” two new items derived from qualitative study: “Have you had difficulties in opening and closing your mouth?” and “Have you felt speech was painful because of problems with your teeth, mouth, dentures, or jaws?” | |

| POST-OHIP-13 [52] | 13 | after treatment | 1—better 0—the same −1—worse | derived from OHIP-20 by the authors’ expertise for the assessment of the OHRQoL after prosthodontic treatment items: 1: chewing, 2: food packing, 3: satisfaction with diet, 4: pain/discomfort, 5: presence of ulcers, 6: denture fits, 7: denture retention, 8: denture comfort, 9: smile, 10: teeth shape, 11: color and position, 12: oral well-being, 13: satisfaction with life | not specified | new items regarding smile, artificial teeth shape, color, and position of artificial teeth | |

| OHIP perception of masticatory efficiency [53] | 7 | 4 weeks | 4—always 3—often 2—occasionally 1—rarely 0—never | derived from OHIP-49 by authors items measuring perception of masticatory efficiency chosen by authors (no. 1, 28, 32, 30, 16, 9, 18) | not specified | tested for internal consistency | |

| OHIP-PD [54] | 14 | not stated | not stated | derived from OHIP-14 (Slade) and OHIP-49 by expert panel | 7 dimensions: functional limitation (3 modified, 1 modified), physical pain (15, 13), psychological discomfort (19 modified, 22 modified), physical disability (27 modified, 28 modified), psychological disability (34 modified, 38 modified), social disability (42 modified, 49 modified), handicap (44 modified, 45 modified) | items adapted to periodontal disease by modifying the wording | |

| OHIP-CP [55] | 18 | not stated | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never I don-t know | phase I: derived from OHIP-49 and other literature sources by panel of experts phase II: quantitative classical test theory and qualitative content analysis with second panel of experts, investigators, and patients phase III: validation | 3 factors pain and functional limitation (14, 15, 13, new item, 1, new item, 5, 7), psychological discomfort (6, 20, 23, 39, 27, 29), psychological disability and social handicap (31, 38, 44, 47) | items relocated into 3 domains New items: “Have you ever had any teeth become loose on their own, without any injury?”, “Have you had bleeding gums spontaneously bleeding or while brushing your teeth or biting hard objects?” | tested for construct, discriminative, and convergent validity, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability |

| OHIP-14-MID-PT [56] | 14 | 1 year | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | OHIP-14 Slade’s version adapted to mild intellectually disable people by collecting data during interview instead of by the self-administrative questionnaire | 7 dimensions functional limitation (2, 6), physical pain (9, 15), psychological discomfort (20, 23), physical disability (29, 32), psychological disability (35, 38), social disability (42, 43), handicap (47, 48) | several modifications to the wording of items | tested for construct, convergent, and divergent validity, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability |

| mOHIP-14 [57] | 14 | not stated | 4—very often 3- fairly often 2- occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never 5—I don’t know 6—not applicable | based on OHIP-14 Slade’s version | Each subscale has a different number of factors in the model: Subscale 1—three-factor model psychological and social limitations (23, 38, 20, 42, 47, 48, 43), physical limitations (9, 32, 35, 15, 29), functional limitations (2, 6) Subscale 2—single-factor model Subscale 3—two-factor model social interaction limitations (20, 15, 38, 23, 9, 32, 29, 35), basic activities disorder and personal discomfort (48, 43, 47, 42, 2, 6) | three subscales obtained by asking the same question in relation to teeth (subscale 1), oral mucosa (subscale 2), and dentures (subscale 3) additional answer “not applicable” for toothless patients in subscale 1 or patients not using dentures in subscale 2 variation in the factors structure depending on the part of the oral cavity | tested for internal consistency |

| OHIP-12 Sign lang. [58] | 12 | not stated | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | derived from OHIP-14 by expert panel questionnaire in sign language in video format two items removed: “Have you had trouble pronouncing any words?” and “Have you been totally unable to function?” | 7 domains functional limitation (1 question), physical pain (2 questions), psychological discomfort (5 questions), physical disability (1 question), psychological disability (1 question), social disability (1 question), handicap (1 question) | items relocated within domains some changes made to the wording due to difficulties in understanding the signs for words such as “shy,” “embarrassed,” and “irritable.” | tested for internal consistency and test–retest reliability |

| OHIP-S14 Ortho [59] | 14 | 1 month | 5—very often 4—fairly often 3—occasionally 2—hardly ever 1—never | derived from OHIP-49 by exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis | 7 dimensions functional limitation (1, 4), physical pain (10, 15), psychological discomfort (22, 23), physical disability (31, 32), psychological disability (34, 35), social disability (42, 43), handicap (47, 48) | the expression “teeth, mouth, or dentures” changed into “brackets” rephrasing some items | tested for content and construct validity, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability |

| MOHIP-14PW [60] | 14 | not stated | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | derived from OHIP-14 | 3 dimensions physical impact (2, 6, 29, 32, 35, 42, 43, 47, 48), psychological impact (20, 23, 38), pain impact (9, 15) | reducing the number of dimensions from 7 to 3 items’ redistribution within subscales based on confirmatory and exploratory factor analysis | tested for internal consistency and test–retest reliability |

| S-OHIP (14) [32] | 14 | not stated | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | derived from OHIP-14 | 7 domains functional limitation (1, 4), physical pain (10, 15), psychological discomfort (22, 23), physical disability (31, 32), psychological disability (34, 35), social disability (42, 43), handicap (47, 48) | OHIP-14 (Slade) modified by changing the expression “teeth, mouth, or dentures” into “salivary problem” | |

| OSHIP-Perio [61,62] | 14 | 6 weeks | 4—very often 3—fairly often 2—occasionally 1—hardly ever 0—never | preliminary OSHIP-Perio derived from OHIP-49 and additional 8 items specific to the periodontal disease added by the expert panel based on a previous study probability-based model used to reduce items of preliminary OSHIP-Perio additional items specific to periodontitis | 7 domains periodontal: 5 new items, functional limitations (1, 2, 8), physical pain (13, 14, 15, 16, physical disability (26), handicap (44) 4 dimensions periodontal: 5 new items, oral function (1, 2), orofacial pain (13, 14, 15), oral function (16, 26), psychological impact (44), item without dimension (8) | exploratory factor analysis used to evaluate dimensionality of preliminary OSHIP-Perio (Oral and Systematic Health Impact Profile) four-dimensional model with a new dimension: periodontal New items: “Have you experienced shaky teeth?”, “Have you experienced bleeding gums?”, “Have you experienced abnormal taste in your saliva?”, “Have you felt that your gums affect your underlying medical conditions/medications affect your gums?”, “Have you felt that your gums affect your underlying medial conditions?” | tested for discriminant, convergent, and concurrent validity, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wojszko, Ł.; Banaszek, K.; Gagacka, O.; Bagińska, J. Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) as a Tool for the Assessment of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life—A Scoping Review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110490

Wojszko Ł, Banaszek K, Gagacka O, Bagińska J. Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) as a Tool for the Assessment of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life—A Scoping Review. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(11):490. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110490

Chicago/Turabian StyleWojszko, Łukasz, Karolina Banaszek, Oliwia Gagacka, and Joanna Bagińska. 2025. "Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) as a Tool for the Assessment of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life—A Scoping Review" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 11: 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110490

APA StyleWojszko, Ł., Banaszek, K., Gagacka, O., & Bagińska, J. (2025). Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) as a Tool for the Assessment of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life—A Scoping Review. Dentistry Journal, 13(11), 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110490