Hemophilic Pseudotumor of the Maxilla Secondary to Endodontic Treatment: Case Report and Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

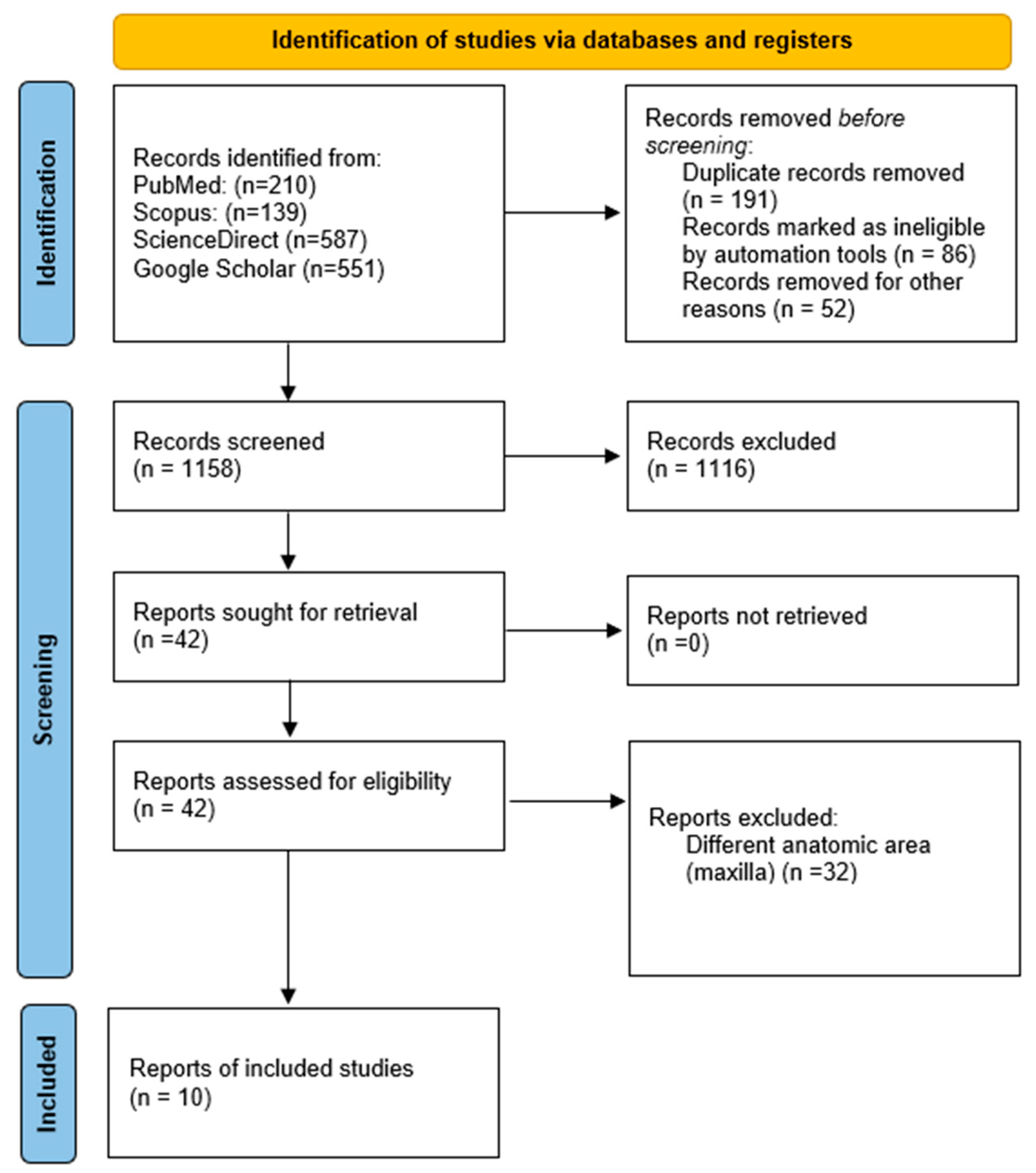

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Sources of Information and Search

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Collection and Summary Measures

2.6. Quality Assessment of Individual Studies

3. Results

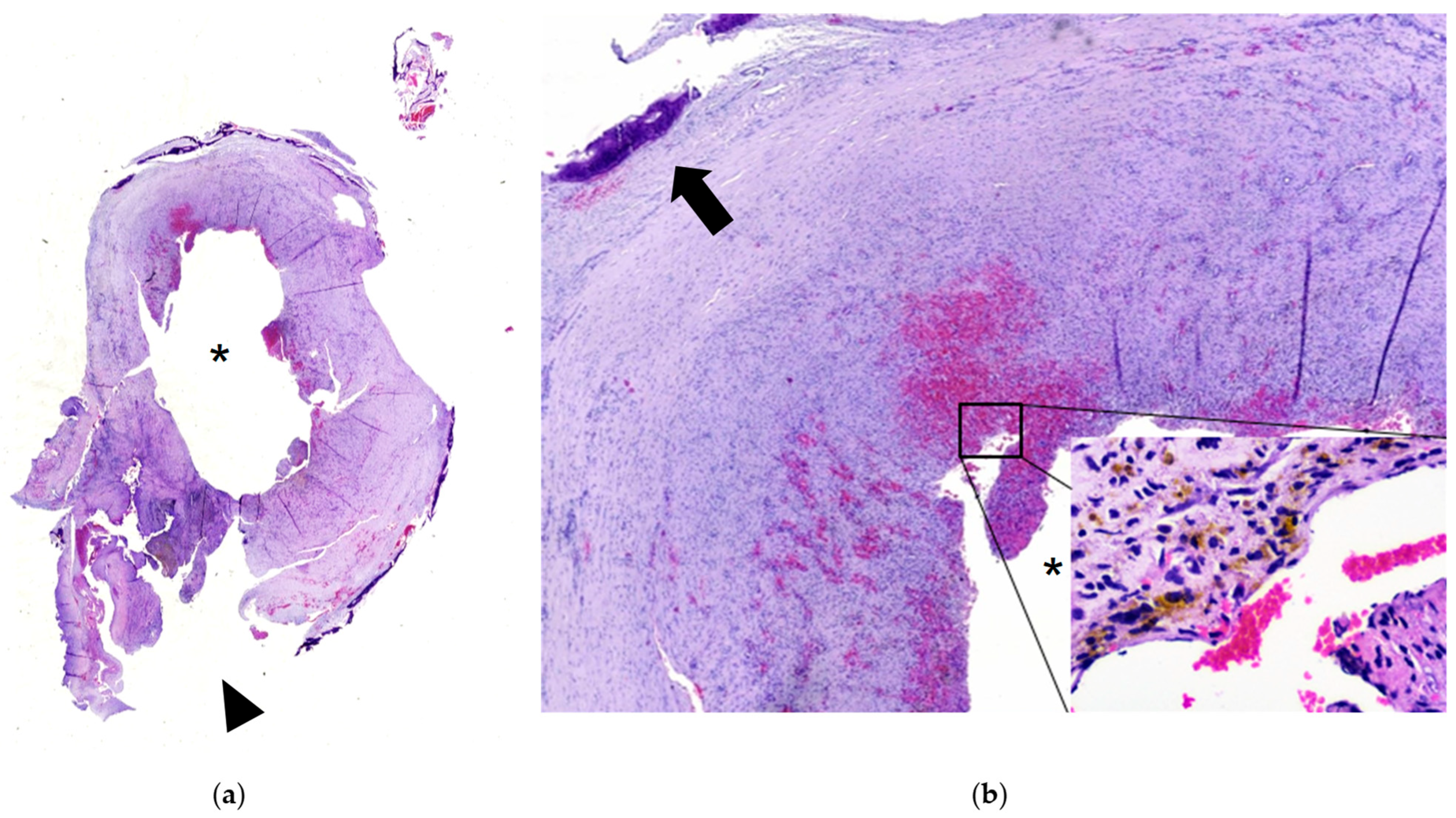

3.1. Case Report

3.2. Systematic Review

4. Discussion

4.1. Gender

4.2. Age

4.3. Type of Hemophilia

4.4. Location

4.5. Etiology

4.6. Clinical Manifestations

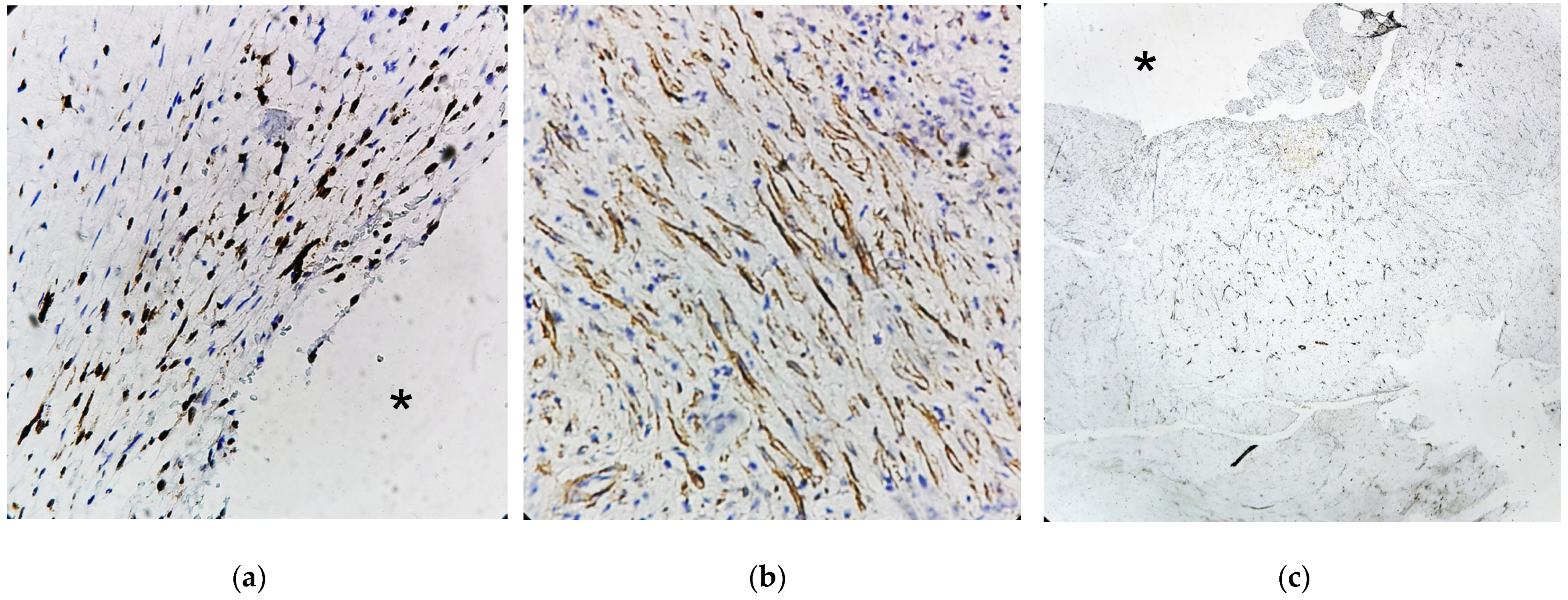

4.7. Histology

4.8. Treatment and Prognosis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HP | Hemophilic pseudotumor |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses |

| JBI | The Joanna Briggs Institute |

| SMA | Alpha smooth muscle actin |

| CD34 | Cluster of Differentiation 34 |

| Ki-67 | Kiel 67 |

| GLUT-1 | Glucose Transporter 1 |

| CD31 | Cluster of Differentiation 31 |

Appendix A. Electronic Literature Review Search Strategy

| Databases Database Link Search Date | Search Strategies | Number of Articles Found |

| PudMed | (Pseudotumor, Hemophilia [MeSh]) AND (Hemophilic pseudotumor) AND (Hemophilic cysts) AND (Hemophilic pseudo tumor) AND (Haemophilic pseudotumor) AND (Haemophilic cysts) AND (Heamophilic pseudo tumor) AND (Maxilla) OR (Gnathic) NOT (Mandibule) NOT (Animal). | 210 |

| ScienceDirect | (Pseudotumor hemophilia) AND (Hemophilic pseudotumor) AND (Hemophilic cysts) AND (Hemophilic pseudo tumor) AND (Haemophilic pseudotumor) AND (Haemophilic cysts) AND (Heamophilic pseudo tumor) AND (Maxilla) OR (Gnathic) NOT (Mandibule) NOT (animal) NOT (Jaw) | 587 |

| SCOPUS | TITLE-ABS-KEY (Pseudotumor AND Hemophilia) OR (Hemophilic AND Cysts) OR (Hemophilic AND Pseudo AND Tumor) OR (Haemophilic AND Cysts) OR (Haemophilic AND Pseudo AND Tumor) AND (Maxilla) OR (Gnathic) OR (Oral) AND NOT (Mandibule) AND NOT (Animal) | 139 |

| Google Scholar | “Pseudotumor hemofilia” or “Tumor hemofilia” or “haemophilia-associated pseudotumour” or “Hemophilic pseudo tumor” or “haemophilic cysts” and “Maxilla” and “Gnatico” and “Oral”. | 551 |

Appendix B

References

- Doyle, A.J.; Back, D.L.; Austin, S. Characteristics and management of the haemophilia-associated pseudotumours. Haemophilia 2020, 26, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira Lima, G.; Ferreira Robaina, T.; de Queiroz Chaves Lourenço, S.; Pedra Dias, E. Maxillary hemophilic pseudotumor in a patient with mild hemophilia A. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2008, 30, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhu, L.F.; Xu, C.S. Successful treatment of hemophilic pseudotumor of maxilla by radiotherapy: A case with 10 years follow-up. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2020, 55, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Arroyo, J.L.; Pérez-Zúñiga, J.M.; Merino-Pasaye, L.E.; Saavedra-González, A.; Alcivar-Cedeño, L.M.; Álvarez-Vera, J.L.; Anaya-Cuellar, I.; Arana-Luna, L.L.; Ávila-Castro, D.; Bates-Martín, R.A.; et al. Consensus on hemophilia in Mexico. Gac. Med. Mex. 2021, 157, S1–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Sun, C.; Sui, T.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, L.; Yang, R. Hemophilic pseudotumor in Chinese patients: A retrospective single-centered analysis of 14 cases. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2011, 17, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, S.O.; de Piratininga, J.; Pinto Júnior, D.S.; de Araújo, N. Hemophilic pseudotumor of the jaws: Report of two cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 1995, 79, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, D.P.; Solar, A.; Huang, J.; Chigurupati, R. Pseudotumor of the mandible as first presentation of hemophilia in a 2-year-old male: A case report and review of jaw pseudotumors of hemophilia. Head Neck Pathol. 2011, 5, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khubrani, A.M.; Alshomer, F.M.; Alassiri, A.H.; AlMeshal, O. Pseudotumor of hemophilia of the thumb. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Merchan, C.E. Hemophilic pseudotumors: Diagnosis and management. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2020, 8, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, D.S.; Barber, M.S.; Kienle, G.S.; Aronson, J.K.; von Schoen-Angerer, T.; Tugwell, P.; Kiene, H.; Helfand, M.; Altman, D.G.; Sox, H.; et al. CARE guidelines for case reports: Explanation and elaboration document. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 89, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnier, J.J.; Kienle, G.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; Sox, H.; Riley, D.S. The CARE guidelines: Consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2013201554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, D.S.; Keast, A.T. An Unusual Cause of Epistaxis: A Haemophilic Pseudotumour in a Non-Haemophiliac, Arising in a Paranasal Sinus. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2002, 116, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.T.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.C. Imaging features of paediatric haemophilic pseudotumour of the maxillary bone: Report of three cases and review of the literature. Chin. Med. J. 2000, 113, 938–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, P.P.; Anim, S.O.; Koutlas, I.G. Maxillary pseudotumor as initial manifestation of von Willebrand disease, type 2: Report of a rare case and literature review. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2016, 121, e27–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, A.Y.; Huh, K.H.; Yi, W.J.; Symkhampha, K.; Heo, M.S.; Lee, S.S.; Choi, S.C. Haemophilic pseudotumour in two parts of the maxilla: Case report. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2016, 45, 20150440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Jin, Y.; Wang, H.; Guo, Z.; Huang, Z. Intraosseous venous malformation of the maxilla after enucleation of a hemophilic pseudotumor: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2020, 8, 4644–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, F.; Shirayama, R.; Ito, T.; Oshida, K.; Sato, T.; Kusuhara, K. Hemophilic pseudotumor of the maxillary sinus in an inhibitor-positive patient with hemophilia A receiving emicizumab: A case report. Int. J. Hematol. 2022, 115, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Lisy, K.; et al. Conducting systematic reviews of association (etiology): The Joanna Briggs Institute’s approach. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Gupta, S.; Aggarwal, S. Spontaneous resolution and bone regeneration in hemophilic pseudotumor: A rare case report and literature review. Spec. Care Dentist. 2024, 44, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.F.; Wang, C.M.; Shieh, W.Y.; Liao, Y.F.; Hong, H.H.; Chang, C.T. The correlation between two occlusal analyzers for the measurement of bite force. BMC Oral Health. 2022, 22, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuva, B.; Ikram, O. Complications in Endodontics. Prim. Dent. J. 2020, 9, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Su, J.; Ye, X.; Xu, W. Conservative management with factor VIII replacement alone for hemophilic pseudotumor in the mandible: A case report. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2022, 40, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (Author(s), Year) | Country | Type of Study | Gender | Age (Years) | Location | Treatment | Follow-Up (Months/Years) | Type of Hemophilia | Intensity of Hemophilia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machado de Sousa 1995 [6] | Brazil | Case series | Male | 11 | Left maxilla second premolar to molar | Replacement therapy | A month | Type A | Severe |

| Stevenson 2002 [12] | New Zealand | Case report | Male | 75 | Left maxillary sinus | Radiotherapy | 18 months | Without hemophilia | NR |

| Siqueira 2008 [2] | Brazil | Case report | Male | 12 | Left posterior maxillary region | Surgery and replacement therapy | 9 months | Type A | Moderate |

| Xue 2011 [5] | China | Case series | Male | 24 | Left maxillary sinus | Replacement therapy | NR | Type A | Moderate |

| Yang 2012 [13] | China | Case series | Male | 1 | Right posterior maxillary region | Replacement therapy | 36 months | Type B | Moderate |

| Yang 2012 [13] | China | Case series | Male | 2 | Left maxillary sinus | Surgery and replacement therapy | 6 months | Type A | Moderate |

| Yang 2012 [13] | China | Case series | Male | 2 | Left posterior maxillary region | Surgery and replacement therapy | 7 years | Type A | Moderate |

| Argyris 2016 [14] | United States | Case report | Female | 11 | Right posterior marginal border of maxilla | Surgery and replacement therapy | NR | von Willebrand disease | NA |

| Kwon 2016 [15] | Korea | Case report | Male | 53 | Hard palate and floor of right maxillary sinus | Surgery and replacement therapy | 3 months | Type B | Moderate |

| Cai 2020 [16] | China | Case report | Male | 11 | Left maxilla | Surgery and replacement therapy | 5 years | Type A | NR |

| Yong 2020 [3] | China | Case report | Male | 11 | Right maxilla | Radiotherapy and replacement therapy | 10 years | Type A | Mild |

| Kawahara 2022 [17] | Japan | Case report | Male | 14 | Left maxilla | Surgery, replacement therapy and antibody treatment | 19 months | Type A | Severe |

| Present case 2025 | México | Case report | Male | 14 | Left maxilla | Surgery and replacement therapy | 12 months | Type A | Mild |

| Author(s) | Q 1 | Q 2 | Q 3 | Q 4 | Q 5 | Q 6 | Q 7 | Q 8 | Q 9 | Q 10 | Overall Score and Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yang [13] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 90% (High) |

| Machado de Sousa [6] | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 80% (High) |

| Xue [5] | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 50% (Low) |

| Author(s) | Q 1 | Q 2 | Q 3 | Q 4 | Q 5 | Q 6 | Q 7 | Q 8 | Overall Score and Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stevenson [12] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 (High) |

| Siqueira [2] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | 87.5 (High) |

| Argyris [14] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 (High) |

| Kwon [15] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | 87.5 (High) |

| Cai [16] | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 87.5 (High) |

| Yong [3] | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | 75 (High) |

| Kawahara [17] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 (High) |

| Our case | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 (High) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quiroz-Gomez, J.R.; Roa-Encarnación, C.M.; Puebla-Mora, A.G.; Hernández-Morales, A.; Padilla-Rosas, M.; Nava-Villalba, M. Hemophilic Pseudotumor of the Maxilla Secondary to Endodontic Treatment: Case Report and Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110491

Quiroz-Gomez JR, Roa-Encarnación CM, Puebla-Mora AG, Hernández-Morales A, Padilla-Rosas M, Nava-Villalba M. Hemophilic Pseudotumor of the Maxilla Secondary to Endodontic Treatment: Case Report and Systematic Review. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(11):491. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110491

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuiroz-Gomez, Jose Rodolfo, Carlos Manuel Roa-Encarnación, Ana Graciela Puebla-Mora, Antonio Hernández-Morales, Miguel Padilla-Rosas, and Mario Nava-Villalba. 2025. "Hemophilic Pseudotumor of the Maxilla Secondary to Endodontic Treatment: Case Report and Systematic Review" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 11: 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110491

APA StyleQuiroz-Gomez, J. R., Roa-Encarnación, C. M., Puebla-Mora, A. G., Hernández-Morales, A., Padilla-Rosas, M., & Nava-Villalba, M. (2025). Hemophilic Pseudotumor of the Maxilla Secondary to Endodontic Treatment: Case Report and Systematic Review. Dentistry Journal, 13(11), 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13110491