Oral Health Status in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Studies where data on oral health status, oral hygiene, or dental conditions in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of ALS were reported;

- Case reports, clinical studies, clinical trials, controlled clinical trials and randomized controlled trials;

- Articles published in English language;

- Human studies.

- Reviews, meta-analyses, letters to the editor, conference and abstracts without full-text availability;

- Animal or in vitro studies;

- Studies where ALS diagnosis was not clearly defined or where data on oral health status as a primary or secondary outcome were missing;

- Duplicates or studies where full text was unavailable.

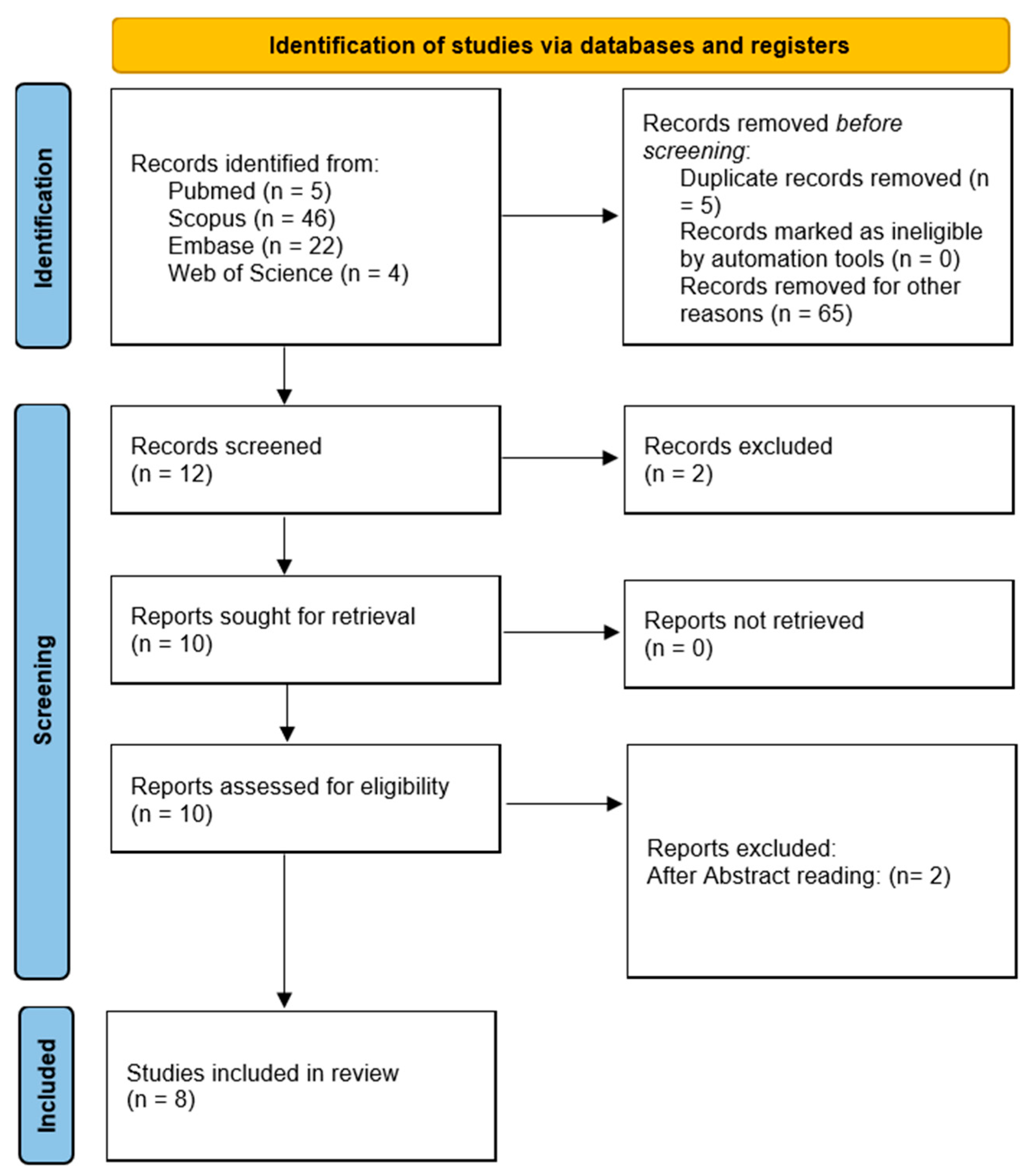

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

3. Relevant Sections

3.1. Oral Hygiene Ability and Motor Impairment

3.2. Caries and Periodontal Disease Prevalence

3.3. Salivary Dysfunction and Drooling

3.4. Impact of Oral Health on Quality of Life and Care

4. Results

4.1. Orofacial Dysfunction and Functional Impairments

4.2. Oral Health Status and Disease Characteristics

4.3. Swallowing Function and Quality of Life

| Authors | Study Design | Setting | N° of Patients | Gender (Male/ Female) | Mean Age (Years) | Oral General Reported Conditions | Type of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis | Assessment Tools | Results (Main Outcome of the Analyzed Study) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paris et al. (2012) [23] | Cross-sectional observational study | Neuromuscular Clinic, Rouen University Hospital, France | 30 | 18 M/12 F | 62 ± 13 | ALS diagnosis confirmed by El Escorial criteria; varied symptoms including bulbar involvement. | ALS diagnosis with bulbar and spinal involvement. | Videofluoroscopic barium swallow Dysphagia outcome severity scale ALS Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS) Norris scores for cranial nerve involvement SWAL-QoL questionnaire for quality of life Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) clinical assessments | Oropharyngeal dysphagia negatively impacts quality of life in ALS patients, especially affecting social interactions, mental health, and causing emotional burden. Quality of life was significantly worse in dysphagic patients, notably in aspects such as eating burden, duration, desire, fear, communication, mental health, and social life, with statistical significance (p < 0.001 to p < 0.05) | Oropharyngeal dysphagia is a common and impactful symptom in ALS, significantly altering patients’ quality of life, particularly social and mental health aspects. Identifying and managing swallowing difficulties are crucial in improving overall well-being. |

| Tay et al. (2013) [21] | Cross-sectional clinical study | Multidisciplinary MND clinic at Bethlehem Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia | 33 | N.A. | N.A. |

8 out of 33 reported regular dental visits 10 of 27 dentate participants required extractions/restorations due to retained roots or caries 3 participants had non-carious cavities, lost restorations, or fractured cusps No participant exhibited probing depths of more than 3 mm | Motoneuron disease | Clinical examination including charting of dentition, restorations, caries, periodontal status Plaque and Gingival Indices Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT) | Oral health status was found to be generally good and not significantly affected by advanced MND, possibly due to the motivation and involvement of both participants and healthcare teams. | Oral health in patients with advanced MND was maintained at a good level, and the motivation of both patients and clinicians likely contributed. The involvement of dental professionals as part of the multidisciplinary care team is recommended. |

| Franceschini et al. (2015) [22] | Observational cross-sectional study | Dysphagia Clinic, UNICAMP Hospital, Brazil | 17 | 11 M/ 6 F | 52.8 ± 10.9 | Dysarthria, dysphagia, reduced QOL related to swallowing | Spinal-onset only | SWAL-QOL Speech Subscale of ALS Severity Scale FEES, Dysphagia Severity Scale FOIS |

| Dysarthria and dysphagia commonly occur in spinal-onset ALS and significantly reduce |

| Punet. et al. (2017) [19] | Cross-sectional observational study | Motor Neuron Disease Unit, Bellvitge University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain; | 153 patients with ALS 23 healthy Patients | 54% M/ 46% F (ALS group) 44% M/ 56% F (healthy group) | 62 (ALS group) 51 (healthy group) | Functional jaw limitations; some received botulinum toxin or non-invasive ventilation | Bulbar involvement and non-bulbar ALS | Jaw Functional Limitation Scale-8 items (JFLS-8) Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS) |

| Bulbar ALS is associated with functional limitation in mastication; balanced UMN/LMN involvement leads to the worst impairments. |

| Bergendal et al. (2017) [15] | Observational longitudinal case series (quality improvement project) | National Oral Disability Centre for Rare Disorders, Jönköping, Sweden | 14 | 5 M/9 F | 62.8 |

All dentate patients, mean number of teeth: 26.7; good baseline oral health | 8 bulbar-onset 6 spinal-onset | Nordic Orofacial Test-Screening (NOT-S) Dental examination Panoramic radiography | Bulbar group showed worse NOT-S scores (initial 5.6 → final 6.1) vs. spinal group (0.7 → 3.2)

| Orofacial functions progressively declined, especially in bulbar cases. With regular support and hygiene aids, oral comfort and health were maintained throughout ALS progression. |

| Punet et al. (2018) [18] | Cross-sectional controlled study | ALS Unit, Bellvitge University Hospital, Spain | 153 ALS patients, 23 controls | 54% M/ 46% F (ALS group) 44% M/ 56% F (healthy group) | 64.2 (ALS group) 52 (healthy group) | Reduced mouth opening, bite force; traumatic self-injury (tongue, cheek, lip); increased sialorrhea | Bulbar, spinal, and respiratory onset | DC/TMD protocol mandibular movement measures bite force finger-thumb grip force tests | Maximum unassisted mouth opening was significantly reduced in ALS patients (both spinal- and bulbar-onset) compared to controls (p < 0.001) Maximum mouth protrusion was significantly reduced, with (p < 0.001) Finger–thumb grip force was significantly lower, with (p < 0.001) Bite force was significantly decreased in bulbar-onset patients (p < 0.001) but not explicitly in spinal-onset patients The prevalence of traumatic mucosal injuries was higher in ALS patients compared to controls (29.9% vs. 8.7%, p = 0.03) No significant increase in TMD prevalence was noted (p > 0.05) | ALS patients, particularly with bulbar onset, show significant reduction in masticatory function and increased self-injury. Dentists should be included in the care team. |

| Nakayama al. (2018) [14] | Single-center, cross-sectional observational study | Sayama Neurology Hospital Japan | 50 | 31 M / 19 F | 70.7 |

The maximum mouth opening was significantly restricted, with an average of 13.7 ± 7.4 mm. Oral health parameters such as dental calculus, bleeding on probing, tongue atrophy or hypertrophy, and tongue coating were assessed, with no significant difference related to disease or TPPV duration | N.A. | Oral health assessments included the community periodontal index (CPI), maximum mouth opening, saliva flow rate, tongue anomalies, and dental conditions | Severe dental disease was uncommon among the hospitalized ALS patients receiving nursing oral care Mouth opening was markedly restricted and negatively correlated with disease duration and TPPV duration No significant correlations were observed between other intraoral parameters and disease or TPPV duration | Early intervention targeting mouth opening restrictions is essential, and maintaining oral health in hospitalized ALS patients can be effectively managed by nurses despite the challenge of restricted mouth opening |

| De Sire et al. (2021) [20] | Cross-sectional clinical study | ALS Center, Neurology Unit, University Hospital “Maggiore della Carità”, Novara, Italy | 37 | 12 M/25 F | 61.19 ± 11.56 |

Poor oral health across all patients (e.g., food debris, tongue coating, gingival inflammation) Strong correlation with sialorrhea and reduced tongue mobility, especially in bulbar-onset ALS | Spinal-onset (SO) Bulbar-onset (BO) | ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R) Brief Oral Health Status Examination (BOHSE) Winkel Tongue Coating Index (WTCI) Oral Food Debris Index (OFDI) Gingival Index (GI) Oral Hygiene Index (OHI) New Method of Plaque Scoring (NMPS) | Oral health was impaired in all patients, independent of functional status Sialorrhea significantly correlated with poor BOHSE and WTCI scores (p = 0.01, p = 0.04) BO patients had significantly lower tongue mobility OFDI negatively correlated with upper limb function (ALSFRS-R UL, p = 0.03) BOHSE and WTCI were significantly negatively correlated with survival time Oral health indices not correlated with cognitive impairment | A poor oral health status is common in ALS patients and may contribute to reduced functional performance and survival time. The study highlights the need for integrating oral healthcare and rehabilitation into the multidisciplinary management of ALS. Oral screening and targeted intervention should become a regular part of ALS care |

4.4. Role of Supportive Care in Maintaining Oral Health

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| NOT-S | Nordic Orofacial Test-Screening |

| UMN | Upper motoneuron |

| LMN | Lower motoneuron |

| JFLS | Jaw Functional Limitation Scale |

| ALSFRS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale |

| SWAL-QOL | Swallowing Quality of Life |

| FEES | Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing |

| FOIS | Functional Oral Intake Scale |

| DC/TMD | Diagnostic Criteria For Temporomandibular Disorders |

| OHAT | Oral Health Assessment Tool |

| ALSFRS-R | ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised |

| BOHSE | Brief Oral Health Status Examination |

| WTCI | Winkel Tongue Coating Index |

| OFDI | Oral Food Debris Index |

| GI | Gingival Index |

| OHI | Oral Hygiene Index |

| NMPS | New Method of Plaque Scoring |

| CPI | Community Periodontal Index |

Appendix A. Search Strategies

| Database | Search Strategy | Filters/Limitations |

| PubMed | (“amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” [MeSH Terms] OR (“amyotrophic” [All Fields] AND “lateral” [All Fields] AND “sclerosis” [All Fields]) OR “amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” [All Fields]) AND ((“oral health” [MeSH Terms] OR (“oral” [All Fields] AND “health” [All Fields]) OR “oral health” [All Fields]) AND “status” [All Fields]) AND ((casereports [Filter] OR clinicalstudy [Filter] OR clinicaltrial [Filter] OR controlledclinicaltrial [Filter] OR randomizedcontrolledtrial [Filter]) AND (humans [Filter]) AND (English [Filter])) | Humans, English, case reports, clinical study, clinical trial, controlled clinical trial, randomized controlled trial |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“amyotrophic lateral sclerosis”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (ALS)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“oral health status”) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“oral health”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (status))) | Document type: article; language: English |

| Embase | (‘amyotrophic lateral sclerosis’/exp OR ‘amyotrophic lateral sclerosis’) AND (‘oral health status’ OR (‘oral health’/exp AND status)) AND ([english]/lim AND [humans]/lim) AND ([article]/lim OR [clinical study]/lim OR [clinical trial]/lim OR [randomized controlled trial]/lim OR [case report]/lim) | Humans, English, case report, clinical study, clinical trial, randomized controlled trial |

| Web of Science | TS = (“amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” OR ALS) AND TS = (“oral health status” OR (“oral health” AND status)) | Language: English; document type: article |

References

- Riancho, J.; Gonzalo, I.; Ruiz-Soto, M.; Berciano, J. Why Do Motor Neurons Degenerate? Actualisation in the Pathogenesis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurología 2019, 34, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sycinska-Dziarnowska, M.; Maglitto, M.; Woźniak, K.; Spagnuolo, G. Oral Health and Teledentistry Interest during the Covid-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patini, R.; Gallenzi, P.; Spagnuolo, G.; Cordaro, M.; Cantiani, M.; Amalfitano, A.; Arcovito, A.; Callà, C.; Mingrone, G.; Nocca, G. Correlation Between Metabolic Syndrome, Periodontitis and Reactive Oxygen Species Production. A Pilot Study. Open Dent. J. 2017, 11, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiò, A.; Logroscino, G.; Traynor, B.J.; Collins, J.; Simeone, J.C.; Goldstein, L.A.; White, L.A. Global Epidemiology of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of the Published Literature. Neuroepidemiology 2013, 41, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Watt, R.G.; Williams, D.M.; Giannobile, W.V.; Lee, J.Y. A New Definition for Oral Health: Implications for Clinical Practice, Policy and Research. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, D.; Carvalho, R.; Machado, V.; Chambrone, L.; Mendes, J.J.; Botelho, J. Prevalence of Periodontitis in Dentate People between 2011 and 2020: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Studies. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2023, 50, 604–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, P.P.; Lindsay, A.; Meng, J.; Gopalakrishna, A.; Raghavendra, S.; Bysani, P.; O’Brien, D. The Prevention of Infections in Older Adults: Oral Health. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selwitz, R.H.; Ismail, A.I.; Pitts, N.B. Dental Caries. Lancet 2007, 369, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansores-España, D.; Carrillo-Avila, A.; Melgar-Rodriguez, S.; Díaz-Zuñiga, J.; Martínez-Aguilar, V. Periodontitis and Alzheimers Disease. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal 2021, 26, e43–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Van Dyke, T.E. Periodontitis and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Consensus Report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, S24–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makizodila, B.A.M.; van de Wijdeven, J.H.E.; de Soet, J.J.; van Selms, M.K.A.; Volgenant, C.M.C. Oral Hygiene in Patients with Motor Neuron Disease Requires Attention: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Spec. Care Dent. 2022, 42, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlMadan, N.; AlMajed, A.; AlAbbad, M.; AlNashmi, F.; Aleissa, A. Dental Management of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cureus 2023, 15, e50602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, R.; Nishiyama, A.; Matsuda, C.; Nakayama, Y.; Hakuta, C.; Shimada, M. Oral Health Status of Hospitalized Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients: A Single-Centre Observational Study. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2018, 76, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergendal, B.; McAllister, A. Orofacial Function and Monitoring of Oral Care in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2017, 75, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Han, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhou, C. Prevalence of Sialorrhea Among Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2022, 63, e387–e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Steele, J. Botulinum Toxin Improves Sialorrhea and Quality of Living in Bulbar Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2006, 34, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera-Punet, N.; Martinez-Gomis, J.; Willaert, E.; Povedano, M.; Peraire, M. Functional Limitation of the Masticatory System in Patients with Bulbar Involvement in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2018, 45, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riera-Punet, N.; Martinez-Gomis, J.; Paipa, A.; Povedano, M.; Peraire, M. Alterations in the Masticatory System in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Oral. Facial Pain. Headache 2018, 32, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sire, A.; Invernizzi, M.; Ferrillo, M.; Gimigliano, F.; Baricich, A.; Cisari, C.; De Marchi, F.; Foglio Bonda, P.L.; Mazzini, L.; Migliario, M. Functional Status and Oral Health in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Cross-Sectional Study. NeuroRehabilitation 2021, 48, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, C.M.; Howe, J.; Borromeo, G.I. Oral Health and Dental Treatment Needs of People with Motor Neurone Disease. Aust. Dent. J. 2014, 59, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa Franceschini, A.; Mourão, L.F. Dysarthria and Dysphagia in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis with Spinal Onset: A Study of Quality of Life Related to Swallowing. NeuroRehabilitation 2015, 36, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, G.; Martinaud, O.; Petit, A.; Cuvelier, A.; Hannequin, D.; Roppeneck, P.; Verin, E. Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Alters Quality of Life. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2013, 40, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, E.L.; Goutman, S.A.; Petri, S.; Mazzini, L.; Savelieff, M.G.; Shaw, P.J.; Sobue, G. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Lancet 2022, 400, 1363–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; An, J.; Park, K.; Park, Y. Psychosocial Interventions for People with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Motor Neuron Disease and Their Caregivers: A Scoping Review. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.E.; Gronseth, G.; Rosenfeld, J.; Barohn, R.J.; Dubinsky, R.; Simpson, C.B.; Mcvey, A.; Kittrell, P.P.; King, R.; Herbelin, L.; et al. Randomized Double-Blind Study of Botulinum Toxin Type B for Sialorrhea in ALS Patients. Muscle Nerve 2009, 39, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giess, R.; Naumann, M.; Werner, E.; Riemann, R.; Beck, M.; Puls, I.; Reiners, C.; Toyka, K. V Injections of Botulinum Toxin A into the Salivary Glands Improve Sialorrhoea in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2000, 69, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, E.; Ellis, C.; Brassington, R.; Sathasivam, S.; Young, C.A. Treatment for Sialorrhea (Excessive Saliva) in People with Motor Neuron Disease/Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 5, CD006981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Liang, S. Roles of Porphyromonas Gingivalis and Its Virulence Factors in Periodontitis. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2020, 120, 45–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonocito, S.; Giudice, A.; Polizzi, A.; Troiano, G.; Merlo, E.M.; Sclafani, R.; Grosso, G.; Isola, G. A Cross-Talk between Diet and the Oral Microbiome: Balance of Nutrition on Inflammation and Immune System’s Response during Periodontitis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaisman, N.; Lusaus, M.; Nefussy, B.; Niv, E.; Comaneshter, D.; Hallack, R.; Drory, V.E. Do Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Have Increased Energy Needs? J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 279, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezzella, V.; Cuozzo, A.; Mauriello, L.; Polizzi, A.; Iorio Siciliano, V.; Ramaglia, L.; Blasi, A. Propolis as an Adjunct in Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy: Current Clinical Perspectives from a Narrative Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorio-Siciliano, V.; Blasi, A.; Mauriello, L.; Salvi, G.E.; Ramaglia, L.; Sculean, A. Non-Surgical Treatment of Moderate Periodontal Intrabony Defects with Adjunctive Cross-Linked Hyaluronic Acid: A Single-Blinded Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 52, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mauriello, L.; Cuozzo, A.; Pezzella, V.; Isola, G.; Spagnuolo, G.; Iorio-Siciliano, V.; Ramaglia, L.; Blasi, A. Oral Health Status in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Scoping Review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13100455

Mauriello L, Cuozzo A, Pezzella V, Isola G, Spagnuolo G, Iorio-Siciliano V, Ramaglia L, Blasi A. Oral Health Status in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Scoping Review. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(10):455. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13100455

Chicago/Turabian StyleMauriello, Leopoldo, Alessandro Cuozzo, Vitolante Pezzella, Gaetano Isola, Gianrico Spagnuolo, Vincenzo Iorio-Siciliano, Luca Ramaglia, and Andrea Blasi. 2025. "Oral Health Status in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Scoping Review" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 10: 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13100455

APA StyleMauriello, L., Cuozzo, A., Pezzella, V., Isola, G., Spagnuolo, G., Iorio-Siciliano, V., Ramaglia, L., & Blasi, A. (2025). Oral Health Status in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Scoping Review. Dentistry Journal, 13(10), 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13100455